28 19 10

28 19 10

08 These sugar mills defaulted on Rs 23 billion loans taken from public sector banks. Here’s how they’re linked to major political players

10 Top City 1: The suburban real estate development that brought down former ISI chief Faiz Hameed

14 A 10,000% return but no sales since 2020: Bela Automotive’s surreal stock surge

19 Just how protected are Pakistan’s contracted workers?

22 Ferozsons launches biologic to treat diabetes

24 New visa policy now in effect: citizens of 126 countries free e-visas to visit Pakistan

28 Trukkr hits cash flow positive to survive the fundraising winter

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz Khan - Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Editorial Consultant: Ahtasam Ahmad - Business Reporters: Taimoor Hassan | Shahab Omer

Zain Naeem | Saneela Jawad | Nisma Riaz | Mariam Umar | Shahnawaz Ali | Ghulam Abbass

Ahmad Ahmadani | Aziz Buneri - Sub-Editor: Saddam Hussain - Video Producer: Talha Farooqi

Director Marketing : Mudassir Alam - Regional Heads of Marketing: Agha Anwer (Khi) Kamal Rizvi (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) - Manager Subscriptions: Irfan Farooq

Pakistan’s #1 business magazine - your go-to source for business, economic and financial news. Contact us: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

These sugar mills defaulted on Rs 23 billion loans taken from public sector banks.

Here’s

More than half of the defaulted amount is being attributed to mills owned by the Omni Group which is allegedly close to President Zardari. Ramzan Sugar Mills is also a major defaulter

By Ahmad Ahmadani

At least 25 sugar mills owned by influential individuals with ties to the country’s political elite have defaulted on loans worth over Rs 23 billion taken from the state owned National Bank of Pakistan (NBP).

The revelations came to light as part of an audit of NBP and revealed a number of major defaulters. Many of these defaulters have strong and often direct ties to government politicians. The sugar industry in Pakistan is one of the most powerful in the country. Almost all of the 91 sugar mills in the country are owned by household name politicians and their families, all of whom belong to different political parties. Profit has covered the nexus between sugar barons and politicians in the past.

Much like many other industries in the country, partition meant a new beginning. In August 1947, there were only two sugar factories in the newly minted state of Pakistan. Most of the sugar mills set up in the colonial era were on the Indian side of the border, and the two in Pakistan were not nearly enough to meet domestic supply.

This was an opportunity. For the first few years of the country’s existence sugar had to be imported which was a major drain on a new state with very little trading power. At the same time, sugar was a high-demand commodity in the subcontinent and plenty of sugarcane was grown in the new state. The 1947-48 production numbers for sugarcane in Pakistan were over 54 lakh tonnes. Nearly 75% of this sugarcane was grown in the Punjab. Since at the time the country’s landed elite were also its political elite, it became clear that many of these landowners that were growing sugarcane would now set up sugar mills, process the sugar and make more money.

The experiment was successful. Keeping in view the importance of the sugar industry, the government setup a commission in 1957 to frame a scheme for the development of the sugar industry. In this way the first mill was established at Tando Muhammad Khan in Sindh province in the year 1961. By 1962 there were six mills in the country and in 1964 the Pakistan Sugar Mills Association (PSMA) had been established and

almost every single sugar mill in the country had a member of parliament on its board of directors. The interests of the sugar industry were disproportionately represented in the legislature and the political patronage that came with this allowed the industry to boom. According to a report of the Competition Commission of Pakistan, the number of mills increased to 20 by 1971 during a period when cane cultivation was incentivized in Sindh through establishment of sugar mills. The size of the industry further increased to 34 by 1980.

But by this point mills were facing a problem. Pakistan’s sugarcane was uncompetitive. Production was low compared to the global average yields and so was sugar extract percentage. This meant imported sugar could actually compete with the local product. To counter this, government policies placed tariffs on imported sugar and even banned it while giving subsidies to local sugar mills. As a result, the number of mills grew and so did the number of farmers growing sugarcane.

In fact, the number of mills grew at such a rate that the government eventually had to stop giving licences because of capacity maximisation issues. Through political patronage and protection through tariff and non-tariff restrictions on imports and generous subsidies, Pakistan went from 41 mills in 1987 to 91 by the mid-2000s before a ban was placed on the establishment of new factories due to excess installed capacity.

During this era in particular the Sharif family was prominent in entering the sugar mill business. They started with the Ramzan Sugar Mills and continued on to establish Ittefaq Mills and many others. There was a crucial difference however. In the beginning, many of the mill owners had also been farmers. The Sharifs were hard-boiled industrialists with not a single green thumb in the entire family. This was also part of a rising trend of non-agriculturalists with political clout entering the country’s sugar industry. If one were to believe what was said in those days, the annual profit from one sugar unit in that period used to be more than enough for setting up a new one.

Of course, the problem was that most of this was a bubble. The fact that Pakistan’s sugarcane was uncompetitive was going to catch up with the mills at some point or the other.

Sources familiar with the matter that have shown Profit the relevant documents said that a significant portion of this debt—approximately Rs 12 billion—is

attributed to eight sugar mills operated by Anwar Majid’s Omni Group. Mr Majid and his Omni Group came to national prominence some years ago due to their alleged involvement with President Asif Ali Zardari. The group was also the subject of a Supreme Court case that also involved the President.

And they aren’t the only ones accused of defaulting. The Sharif family’s Ramadan Sugar Mill is another notable defaulter, with an outstanding loan of Rs 2.59 billion. Meanwhile, Ramzan Sugar Mill has failed to repay a loan of Rs 62 crores to the National Bank, further compounding the institution’s financial woes. The situation has brought to light the dire state of debt recovery and financial management within the National Bank, raising concerns about the potential waiver of these massive debts, said sources.

According to available documents, NBP has admitted its failure to collect these debts, acknowledging the losses incurred due to its inability to secure repayment. The Auditor General has criticised the National Bank for its negligence in not securitizing these loans as per policy, pointing to weak financial management and a lack of accountability within the institution. During the audit of NBP for the year 2022, it was observed that the management granted advances/loans of Rs 15.28 billion to various sugar mills. However, the management failed to recover the amount of loans from the said sugar mills and the amount was shown as a loss. This indicated that the loans/advances were not properly secured as per prevailing policies of State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) which resulted in non-repayment of loans of Rs 23.35 billion (a principal of Rs 15.28 billion and interest of Rs 8.07 billion), said the available document.

The audit was of the view that non-recovery of loans tantamount to gross negligence and weak financial management by the NBP authorities resulted in massive loss to the bank, read the document.

Sources also said that this failure in debt collection is poised to lead to significant financial losses for the bank, with the possibility of waiving both the loan amounts and the accrued interest now under consideration.

As per sources, the potential waiver of these loans has sparked outrage, as it would set a precedent for influential individuals and entities to escape financial accountability, further eroding public trust in the banking system. This is not the first time that sugar mills owned by powerful figures have had their debts waived, raising questions about the fairness and transparency of the financial system, they added. n

By Abdullah Niazi and Shahab Omer

This is not the first time a high-ranking military official has faced a very public court martial, through retired Lt Gen Faiz Hameed’s court martial proceedings are certainly unusual.

It was only five years ago that Lt Gen Javed Iqbal Awan was sentenced by the Field General Court Martial (FGCM) to 14 years in prison for espionage.

In the 1990s, Maj General Zaheer ul Islam Abbasi and 38 other officers were court martialed on charges of plotting to storm a corps commanders’ meeting, assassinating Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto and Army Chief General Waheed Kakar, and taking over the country in a coup d’etat. In more recent times, Brigadier Ali Khan along with four majors was arrested, court martialed, and sentenced over links with the banned Islamist organisation Hizb ut Tahrir in 2011.

Like most militaries in the world, the Pakistan Army has an internal justice system to deal with the wrongdoings of its officers internally. The Army Act of 1952 regulates the legal code within the military, mainly for prosecuting military personnel and associated civilians. The act gives the military relative freedom to prosecute and deal with its officers as it sees fit. And while the more famous examples of court martials have to do with espionage, the military has also used it to prosecute financial misdealings.

There is no set precedent for how the military deals with these matters. Perhaps the most significant financial scandal involving the Pakistan military was the August Submarine Scandal, in which retired Admiral Mansur ul Haq, a former Chief of Naval Staff, was fined $7.5 million for taking bribes and stripped of his rank (although it would later be restored by the Sindh High Court). But the case was heard and decided by an accountability court instead of a military one.

In 2009, when the National Assembly’s Public Accounts Committee found irregularities worth billions of rupees during an inquiry into the National Logistics Cell, Army Chief General Ashfaq Pervez Kiyani decided to court martial two retired Army lieutenant generals, Khalid Munir Khan and Afzal Muzaffar, instead of referring the matter to an accountability court.

As retired Lt Gen Faiz Hameed prepares his defence for his own court

martial, he might be considering the precedent that exists already. What he might also realise, however, is that his court martial is a little unique. Up until this point, the military has only really used the Army Act of 1952 to prosecute officers involved in internal affairs, whether those are financial or administrative. In the case of General Faiz, his court martial has to do with a housing society that does not have anything to do with the Army, at least not directly.

The retired lieutenant general is charged with misusing his position to extort money from a private housing society by the name of Top City. This is an entirely private housing society and the case against the former spymaster first went to the Supreme Court. The decision to initiate the court martial was actually made in compliance with the direction of the Supreme Court. As this publication’s parent paper pointed out in a recent editorial, the response from the Pakistan Army has been measured, professional, entirely appropriate, and in line with the Supreme Court’s rulings. But why did it come to this?

What exactly is this case surrounding a real estate project that has brought one of Pakistan’s most powerful military officials to the point of a court martial? To understand the full scale of the story, we must take a jump back exactly two decades ago.

It was 2004, and the concept of suburban housing societies on the outskirts of major cities was just taking off in Pakistan. As developers started buying land an area of particular activity was the land right outside Islamabad. It was here that Top City first got its start. Located just outside Islamabad, the land for Top City was located close to where the new Islamabad International Airport was to be built. Some land was acquired here by a property developer by the name of Iftikhar Ali Waqar.

The land was designated Banjar Qadeem, meaning it had no agricultural or other use and could be purchased from the government for development work. As a report from 2017 published in Daily Times points out, the land was purchased for Rs80 lakhs (then equal to approximately $76,000) which Waqar had borrowed from his sister Zahida Aslam, who is a British-Pakistani and resided in the UK.

After purchasing the land he set about constructing the housing society. It did not go according to plan. Top City did not have much going for it. Located near the new Islamabad International Airport, the project faced scepticism from potential investors

who were wary of the area. Back then, the land surrounding the airport was seen as a risky venture, far removed from the established sectors of Islamabad where the Capital Development Authority (CDA) had already made significant developments. A big concern was that land could be acquired for the airport any day.

Investors were hesitant, their confidence shaken by the market’s general distrust of new projects like Top City. The prevailing fear was that these ventures would simply collect money from the public and then disappear, leaving nothing but broken promises in their wake. The allure of established sectors in Islamabad, where the real estate market was thriving, further diminished interest in this fledgling project.

On top of this, dealings between Waqar and his sister started to go south. Because of the relative failure of the society, Zahida took over the society from her brother. Those close to Waqar claim he was not a willing participant in this, but because he owed money to his sister he could not quite do much.

By the following year, in April 2018, Iftikhar was dead, having taken a gun to end his own life publicly. In a bid to completely distance herself from this turn of events, Zahida promptly packed her bags and headed back to London where she began asking friends to recommend a trusted manager to oversee the venture. Her spiritual guide, or Pir, who went by the name of Dr Naushad, came up with the name of Kunwar Moiz.

Kunwar Moiz is an eccentric character. He is wealthy and he is a bit of a show off. In 2018 he imported a golden Lamborghini from the United Kingdom and made a big fuss about the amount he had paid in taxes to have it imported. He likes to travel in convoys and have a troupe around him at all times.

But he was also savvy in his real estate dealings. When he first took over Top City, he knew the project was in a bad position. However, there is a classic handbook for how to make projects like this soar in Pakistan and Moiz decided to apply it.

Here is how it works. Whenever a developer launches a housing scheme, they almost never have enough money on their own to buy a large enough tract of land to impress possible buyers. Instead, they go on a marketing campaign in which they announce a new housing scheme, often getting celebrity endorsements and pasting huge advertisements all over the cityscape. They then offer what they call ‘advance booking’ and present it as a chance to be some of the first people to buy plots for cheap in the new society.

The money from these advance bookings allows them to put together enough capital to actually be able to buy the land required for the project. The people investing are told their plots are still in the development stage and they will only be told where their plot is once the technical aspects of mapping and zoning are figured out. The truth is that the land has not yet been purchased by the real estate developer and hence no actual, legally enforceable titles to property are being given to the buyers.

So how do they get people to buy these prospective plots that they cannot even see or visit? Every savvy developer hires an army of local property dealers on commission to sell “files” for their scheme. The “files” contain flimsy pieces of paper that are essentially IOUs issued by the real estate developer that state the size of the plot and approximate location of the plot. These are not enforceable in any court of law and if you take the developer to court, the law will not back your claim. At all.

Now, you might think that this is simply an issue of semantics of what customers are promised and shady selling techniques, except the problem goes deeper than this. For example, if not enough people buy these “files”, the real estate developer does not have enough cash to continue the development, the project is halted, and the people that bought the files could have tied up their money for decades to come. (Sure, tell us more about how real estate is “safer” than stocks.)

Kunwar Moiz decided to pursue this strategy but on steroids. He understood the odds and decided to play a different game. They set the prices of their plots remarkably low and introduced an enticing option: instalments. It was a bold move. At that time, a 10-marla (300 square yard) plot in Top City-1 could be yours for just Rs600,000, and even that could be paid off in easy instalments. It was a bargain too tempting to ignore, even for the most cautious investors.

Slowly but surely, investors began to take notice. They started investing, albeit cautiously, knowing full well that it was a gamble. But the low prices meant that the risk was manageable, and so, the first few brave investors took the plunge. However, the market remained sluggish. The resale value of those plot files was dishearteningly low; a file purchased for Rs6 lacs could only be resold for Rs4 lacs. It was a tough situation, but rather than selling at a loss, many investors decided to hold onto their files, hoping that time would bring better fortunes.

And indeed, time proved to be a great ally. In 2010, a new chapter began when the management of Top City-1 changed hands. The period from 2015 to 2017 brought new

challenges. Rumours began to circulate that the government was planning to expand the airport, and that many of the surrounding housing societies, including Top City-1, would lose significant portions of their land to this expansion. These rumours created a wave of panic, causing sales to plummet as investors once again hesitated, unsure of what the future held.

Fortunately, these rumours eventually faded, and with them, the fears that had gripped the market. Sales began to pick up again. The society had secured all the necessary approvals from the Rawalpindi Development Authority (RDA) and the Civil Aviation Authority, solidifying its legitimacy and boosting investor confidence.

By 2017, those same 10-marla plots that once sold for Rs6 lac were now valued at over Rs1 crore — a staggering 16.7x increase that no one could have predicted in those early, uncertain days. But it seemed the bubble might be ready to burst.

This is where things get really interesting. Up until 2017, it seemed that Zahida Aslam had made the right decision by asking Kunwar Moeez to take over the society. The only problem was that Zahida herself was being pushed out. Suburban real estate developments in Pakistan are already murky and a mess to figure out ownership. Zahida had only taken over because her brother, who was the original owner of the land, had taken the money from her to begin the project.

Zahida claims that after obtaining power of attorney from her, Kunwar Moeez declared himself the Chief Executive of the society. The situation was further complicated by a longstanding dispute over 450 kanals (56.25 acres) of land with local residents. This dispute was investigated on the orders of the former Deputy Commissioner of Rawalpindi, leading to an anti-corruption case against three officers from the Punjab Revenue Department.

Adding to the drama, a post appeared on Top City-1’s social media page seven years ago, accusing Zahida Javed, the woman who had levelled accusations against Kunwar Moeez, of being involved in a fraud case herself. The post alleged that she had fraudulently transferred her late brother’s valuable vehicles to her own name, a deception that was caught by the Islamabad Excise and Taxation Department.

This is also where the involvement of retired Lt General Faiz Hameed allegedly comes in. According to the petition submitted to the Supreme Court by Kunwar Moeez, on May 12, 2017, the Rangers and ISI officials

raided the offices of the housing project and the residence of Moeez in connection with a purported terrorism case and took away gold and diamond ornaments, money and other valuables. The action was reportedly taken on behalf of Zahida Aslam. At the time, Faiz Hameed was the director general of the counter-intelligence wing of the ISI.

One source close to the story reports that General Faiz’s brother, Sardar Najaf, was had bought some plots in Top City and was worried about the impact the struggle between Zahida and Kunwar Moeez would have on his investment. In her complaint, Ms Aslam claimed that Mr Moeez used to look after her real estate business in return for a monthly salary. She claimed Mr Moeez transferred the properties to his own name in an allegedly fraudulent manner, and when she tried to recover her ownership of them, he threatened her with dire consequences.

According to Dawn’s coverage of events, Mr Moeez, on the other hand, contended in his petition that Gen Faiz’s brother Sardar Najaf mediated and tried to resolve the issue. After a Rawalpindi-based anti-terrorism court (ATC) acquitted him in the terrorism case, the petition claimed, Gen Hameed contacted him through his cousin — a brigadier in the army — to arrange a meeting. The petition claimed that during the meeting, Gen Hameed told Mr Moeez that he would return the items taken away during the raid, except for 400 tolas (150 troy ounces, or 4.68 kilograms) of gold and cash. At 2017 prices, the gold would have been worth approximately $188,000 (approximately Rs2 crore at the time).

The petition alleged that retired brigadiers Naeem Fakhar and Ghaffar of the ISI “forced” the petitioner to “pay 4 crores [rupees] in cash” and “sponsor a private TV network for a few months”. The Supreme Court, however, asked the petitioner to approach the relevant forums, including the defence ministry, for redressal of his grievances.

The ownership drama and the involvement of Lt General (retired) Faiz Hameed is just one aspect of this entire episode. There are many other controversies surrounding this project. In April 2022, a storm of accusations hit the management of Top City-1. A woman named Uzma Shakeel filed a complaint with the Rawalpindi CPO, accusing the management and employees of trying to seize her 8-kanal piece of land, a property she claimed had been rightfully hers since a local dispute in 2021 had resolved in her favour. According to her, the management had demolished two houses and the boundary wall on her land, taking

with them valuable items, including solar panels and a generator. She claimed losses amounting to Rs60 to 70 lacs and demanded compensation.

Despite her complaints, no case was immediately registered, prompting Uzma to take her petition to a local court in Rawalpindi. The court responded by directing the SHO of Nasirabad to record her statement and take appropriate legal action.

This was not the first time Top City-1 had faced legal troubles. Earlier, another case had been filed at the Nasirabad police station on behalf of 18 people, all related to a land dispute. And in 2022, reports of violent, armed actions by the management further tarnished the project’s reputation.

One official from the Rawalpindi Board of Revenue, who spoke on condition of anonymity, revealed that the society had become a significant security risk for the surrounding communities due to an ongoing ownership dispute over 1,000 kanals (125 acres) of land. This dispute escalated to the point where there were daytime shootouts between Top City-1 employees, security guards, and local residents, turning the area into a virtual warzone.

Despite numerous complaints and even a police case, no significant progress was made. The violence and intimidation cast a long shadow over Top City-1, causing many to question the ethics and safety of the project.

The initiation of court martial proceedings against retired Lt General Faiz Hameed is a rare occasion of things working. While it is unfortunate that an individual who held such high office is being implicated in something of this nature, it is also part and parcel of accountability.

Initially, we see that the Supreme Court saw the matter and exercised restraint. Mr Kunwar Moeez had not approached the defence ministry initially because he was afraid they would not take action against the former spymaster given his rank and esteem in the military. The Supreme Court decided to allow the defence ministry and the army the opportunity to address the matter themselves which they have now done so in a professional manner.

The matter will be heard by the military court which will then make a decision either way. While this will not necessarily give clarity to the many investors of Top City, it will help by establishing who is in control of the housing society project. Then perhaps many of those involved in the project as investors might get a chance to liquidate their money. n

As the stock price of a defunct auto parts manufacturer skyrockets, questions abound. What’s driving this exuberance, and why do investors remain uneasy?

By Zain Naeem

In the tumultuous world of stock markets, stories of dramatic comebacks are not uncommon. Share prices rise and fall, often with little immediate connection to the fundamentals of the underlying companies. Yet, the recent meteoric rise of Bela Automotive—a company that hasn’t sold a single product since 2020—has left even the most seasoned market watchers scratching their heads.

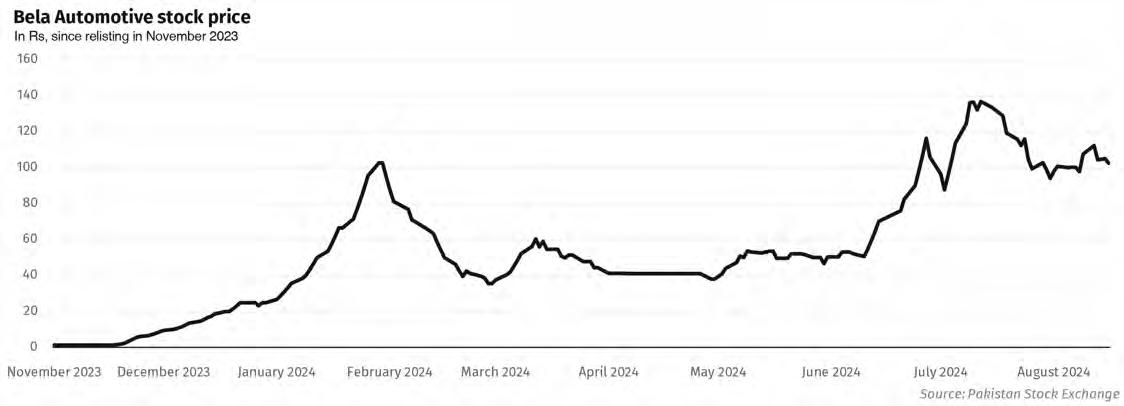

The company, a perennial underperformer, was delisted in 2012 and remained out of sight until its surprising reappearance on the

stock exchange in November 2023. Despite its bleak financial history, including accumulated losses that have steadily mounted for over a decade, Bela’s stock price has surged by an eye-watering 10,000%. For a firm that has consistently failed to make a profit and ceased operations four years ago, this exuberant rally seems, at best, counterintuitive and, at worst, indicative of something far more concerning.

To make sense of this enigma, it is essential to delve into Bela Automotive’s troubled past and the strange forces currently propelling its stock.

Bela Automotive was established in 1983, becoming a public limited company just two years later. Located in Hub Chowki, Balochistan, the firm was involved in manufacturing automotive parts, including precision cold-forged components, bicycle parts, and various high-tensile bolts, nuts, and screws. By 1994, Bela had been listed on the stock exchange, but it quickly became clear that the company was not destined for greatness.

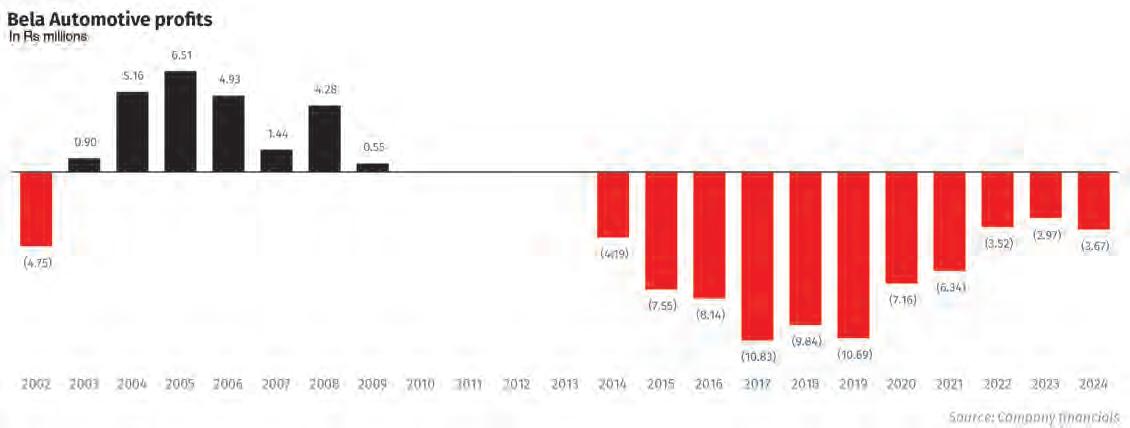

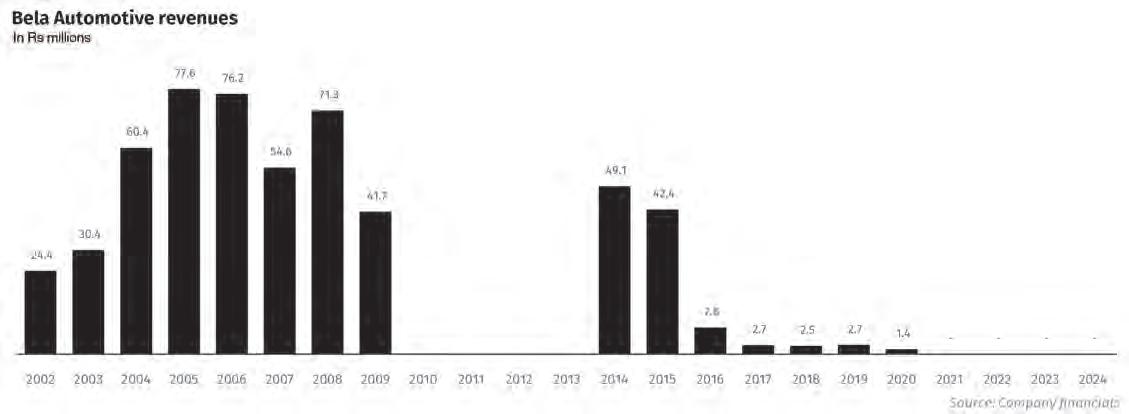

From the outset, Bela struggled to carve out a niche in a competitive market. By 2002, the company was already grappling with losses, which had accumulated to approximately Rs7 million. Although Bela experienced a brief upswing between 2003 and 2005, with revenues climbing to Rs78 million and profits reaching Rs6.5 million, this proved to be the high-water mark. From then on, it was a steady decline.

That decline, in turn, was likely not helped by the macroeconomic environment. The global financial crisis of 2008 had a significant impact on emerging markets

like Pakistan, leading to reduced consumer spending and tighter credit conditions. For a company like Bela, which was already operating on thin margins, these challenges proved insurmountable.

Additionally, the fluctuating value of the Pakistani rupee made it difficult for Bela to manage its costs, particularly as the company relied on imported materials for its manufacturing processes. With the cost of inputs rising and demand for its products falling, Bela found itself in an increasingly precarious financial position.

By 2013, Bela’s sales had dwindled to a mere Rs50 million. This downward trajectory continued until 2019, when the company’s revenues had all but vanished, standing at a paltry Rs1.5 million. The following year, Bela shuttered its operations entirely, citing insurmountable challenges. The company had effectively ceased to exist as a functioning business.

Yet, while Bela’s operations were winding down, its financial woes were just beginning to mount. By 2023, accumulated losses had ballooned to Rs54 million, and the company was teetering on the brink of insolvency. The only thing keeping Bela afloat was a revaluation surplus of Rs95 million, which kept the company’s equity from sinking into the red. The balance sheet showed assets totaling Rs246 million, including Rs146 million in property, plant, and equipment, and Rs74 million in inventory. On the liabilities side, the company had current liabilities of Rs130 million and non-current liabilities of Rs2 million, with trade payables and short-term loans adding up to a significant portion of this burden.

In summary, by 2020, Bela Automotive was little more than a shell, burdened by debt and devoid of operational activity. Its delisting from the stock exchange in 2012 seemed almost merciful—a fitting end to a company that had long been in decline.

The story should have ended there. But in 2023, Bela Automotive made a surprising return to the stock exchange. The company, which had been inactive for over a decade, suddenly found itself back in the spotlight. This time, however, the attention it garnered was far from flattering.

Despite having been dormant for years, Bela’s stock price began to soar almost immediately upon its relisting. In just three months, the price of Bela’s shares jumped from Rs1.3 to a staggering Rs102.49, only to fall back to Rs35 shortly thereafter. The volatility continued, with the stock oscillating between Rs30 and Rs50 before rocketing to Rs137 in a single month. Over an eightmonth period, the share price had increased a hundredfold.

Such a dramatic surge in share price would typically suggest that the company was undergoing a remarkable turnaround, perhaps through a new product launch, a lucrative acquisition, or a strategic partnership. But in Bela’s case, there were no such developments. The company remained as it had been for years: inactive, loss-making, and with no sales to speak of.

So, what explains the sudden surge in Bela’s stock price? Is this a case of irrational exuberance, or is there something more sinister at play?

To understand the full scope of Bela Automotive’s predicament, one must consider the various legal challenges the company has faced over the years. These disputes have cast a long shadow over the company’s operations and have played a significant role in its current state of affairs.

One of the most significant legal battles involved a protracted dispute with Habib Bank, Bela’s largest creditor. The company had taken out a loan to finance the import of machinery worth $1.15 million, a loan that was later converted into Pakistani rupees and rescheduled in both 1996 and 1998. However, Bela failed to make the necessary payments, and the bank began to levy interest and penalties on the outstanding balance.

Bela contested these charges, claiming that the bank had imposed “unlawful and fictitious” markups, which had inflated its liabilities. In 2001, the company filed a lawsuit against Habib Bank, seeking damages of Rs599 million. The bank, in turn, filed its own suit to recover the outstanding dues.

The dispute was complicated by the lack of clarity around the exact amounts owed. Despite requests from auditors for confirmation of the bank’s claims, Habib Bank did not respond, leaving the auditors unable to verify the figures. This impasse persisted until 2009 when the courts ordered an investigation by a recognized chartered accountants firm. Even then, the matter remained unresolved for years.

The company’s legal troubles were compounded in 2014 when the Income Tax Department froze its bank accounts, claiming that Bela had failed to pay taxes. The company contended that the tax authorities had acted illegally, relying on outdated data and issuing an order without giving Bela a chance to present its case. Although the accounts were eventually unfrozen, the damage had been done. Bela’s customers had lost faith, and the company’s reputation suffered a blow from which it would never fully recover.

The final blow came from Bela’s auditors, who began to question the company’s viability as a going concern. With its working capital depleted and its liabilities continuing to mount, Bela’s future looked increasingly bleak. The auditors issued a qualified opinion on the company’s accounts,

casting doubt on the accuracy of its financial statements and further undermining investor confidence.

By 2020, the cumulative impact of these legal battles, financial mismanagement, and operational challenges had taken its toll. Bela Automotive was a company in name only, with no products to sell, no customers to serve, and no future prospects.

Given this dismal state of affairs, Bela’s return to the stock exchange in 2023 is puzzling, to say the least. The company’s relisting was ostensibly the result of a concerted effort to rectify its past non-compliances. Bela had finally paid its regulatory fees, released its long-overdue financial statements, and held annual general meetings as required by

the stock exchange’s rules. The company also claimed that it was on the verge of restarting its operations, with plans to resume production in 2024.

Despite these efforts, the stock exchange initially refused to relist Bela, citing the company’s continued operational inactivity and the qualified opinion issued by its auditors. However, in October 2023, the stock exchange relented, and Bela’s shares were once again available for trading.

What followed was a rollercoaster ride that defied all logic. Within days of being relisted, Bela’s share price began its dramatic ascent, drawing the attention of investors and regulators alike.

The mystery behind the surge

The extraordinary rise in Bela’s share price has raised more than a few eyebrows. While the initial optimism surrounding the company’s return to the stock exchange may have been understandable, the sheer magnitude of the price increase has led many to suspect foul play.

In late December 2023, Bela’s management announced that it had received an offer from Amir Noman, a businessman who runs a spare parts business called United Auto Centre, to acquire a 50% stake in the company. The offer price was disclosed at Rs5 per share, far below the inflated market price. The directors of Bela stated that they were in the process of negotiating the terms of the sale, and the announcement was made in accordance with Section 111 of the Companies Act 2017.

The announcement of a potential acquisition might explain some of the initial

enthusiasm around Bela’s stock. However, it does not account for the subsequent fluctuations in the share price, nor does it explain the continued volatility that has characterized Bela’s stock since its relisting.

Indeed, the offer from Noman seems to have muddied the waters further. Under the terms of Section 111, Noman is required to make a public offer for 25% of the remaining shares in addition to acquiring 50% of the company. This provision is intended to protect minority shareholders by giving them the opportunity to exit at a fair price. However, it also raises the question of whether the current market price reflects the true value of Bela’s shares or if it is being artificially inflated by speculative trading.

To understand the surge in Bela’s stock price, it is important to consider the role of market psychology. In financial markets, investor sentiment often plays a crucial role in driving price movements, sometimes to the detriment of rational analysis.

In the case of Bela, it is possible that the stock’s low price attracted the attention of speculative traders looking for a quick profit. As more investors piled into the stock, the price began to rise, creating a feedback loop that drove the price even higher. This phenomenon, known as a “momentum trade,” can result in significant price movements in a short period of time, even if there is no fundamental reason for the price increase.

Another factor that may have contributed to the surge is the rise of social media and online trading platforms. In recent years, there has been a growing trend of retail investors using these platforms to discuss and trade stocks, often with little regard for traditional valuation metrics. This has led to

the emergence of so-called “meme stocks,” where prices are driven more by social media buzz than by any underlying business performance.

While market psychology and the rise of social media can explain part of the surge in Bela’s stock price, there are also concerns that the rally may have been driven by more nefarious means. In particular, there are fears that the stock may have been subject to manipulation by market participants looking to profit from the increased volatility.

Market manipulation can take many forms, from spreading false information about a company to engaging in practices like “pump and dump,” where a stock is artificially inflated before being sold off at a profit. In the case of Bela, there have been allegations that certain traders may have engaged in coordinated efforts to drive up the stock price, although these claims have yet to be substantiated.

If these allegations are true, it would not be the first time that a company has been subject to such practices. In 2021, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filed charges against a group of traders who were accused of manipulating the price of several stocks, including GameStop, a U.S. retailer that became the poster child for the “meme stock” phenomenon. Even the largest, most mature stock markets, it seems, are not immune to such irrationality.

The case of Bela Automotive highlights several key lessons for investors, particularly those operating in emerging markets like Pakistan. First and foremost, it underscores the importance of conducting thorough due diligence before investing in any company, particularly one with a troubled history.

Investors should also be wary of stocks that have seen sudden and unexplained price increases. While it’s possible that these price movements are driven by genuine market

enthusiasm, they could also be the result of manipulation or speculative trading. In such cases, it’s crucial to approach the investment with caution and to be prepared for the possibility of significant volatility.

Another important lesson is the need to stay informed about the broader economic and regulatory environment. In emerging markets, where economic conditions can change rapidly, it’s important to consider how factors like inflation, currency fluctuations, and political instability could impact the performance of a company or the market as a whole.

Finally, the Bela case highlights the importance of diversification. By spreading investments across a range of assets and sectors, investors can reduce their exposure to the risks associated with any single company or market. This is particularly important in volatile environments where the fortunes of individual companies can change rapidly.

As Bela Automotive’s share price continues its wild ride, the company’s future remains uncertain. There are still far more questions than answers. How can a company with no sales, no profits, and no clear path to recovery command such a high valuation? What role, if any, have market manipulators played in driving up the price of Bela’s shares? And, perhaps most importantly, what will happen once the dust settles?

For now, investors would do well to tread cautiously. Bela’s stock may be riding high, but its foundations remain shaky at best. In a market where perception can be more powerful than reality, it is all too easy for dreams of quick profits to turn into nightmares. The story of Bela Automotive serves as a stark reminder that in the world of investing, not all that glitters is gold. n

The Supreme Court’s ruling promised equality, but in practice, have the companies caught on?

By Zain Naeem

In Pakistan, the plight of the workforce often escapes the scrutiny of its corporate titans. Labour laws, especially those concerning the rights of contracted workers, have long been an overlooked aspect of the country’s economic landscape. But in December 2017, the Supreme Court of Pakistan delivered a landmark ruling that was set to redefine the rules of the game. The verdict declared that contracted employees should be afforded the same rights as permanent employees—a move that, on paper, was revolutionary. Yet, the question remains: do companies really see it that way?

The court’s decision was expected to send shockwaves through the employment market. It broadened the definitions of contract and third-party employment, and mandated that many of these workers be regularized, even applying this retrospectively. The ruling

elevated the status of contracted workers, positioning their rights as a fundamental element of citizenship, not just a legislative afterthought.

Before this ruling, the distinction between permanent and contracted workers was stark. Permanent employees enjoyed the security of better wages, retirement benefits, paid overtime, and the luxury of leaves and vacations. Contracted workers, however, were seen as a disposable extension of the workforce—hired through third parties, they were let go as soon as the seasonal demand subsided.

This system offered companies the flexibility to scale their workforce up or down without the financial burden of long-term benefits. The cost savings were so substantial that many factory owners developed elaborate schemes to keep the majority of their workforce on a contractual basis, even resorting to practices like hiring workers for just 89 days to avoid the 90-day threshold that would require them to be classified as permanent.

The Supreme Court’s ruling aimed to curb these exploitative practices. The intent was clear: it was no longer viable for seths to follow the letter of the law while ignoring its spirit. But what has this meant for companies in the short term?

One immediate impact was the anticipated rise in salary expenses, as companies were now required to treat all employees equally. This raised questions about which sectors would feel the squeeze the most. The auto industry, heavily reliant on contracted labour to meet fluctuating demand, stood out as particularly vulnerable.

Contractual labor has been a cornerstone of Pakistan’s corporate strategy, particularly within industries that demand flexibility and cost

efficiency. The original system, which distinguished between permanent and contracted workers, provided companies with significant advantages that were too enticing to ignore. Understanding why contractual labor became so prevalent in the first place requires an exploration of the economic and operational incentives that drove this trend.

At its core, the use of contractual labor was a response to the need for adaptability in production. Companies, especially those in sectors like automotive manufacturing, faced seasonal fluctuations in demand. Permanent employees, who were entitled to a range of benefits such as incremental wages, retirement benefits, and paid leave, represented a fixed cost that could become burdensome during periods of low demand. In addition, they are harder to fire.

In contrast, contracted workers could be hired for short stints to meet temporary production spikes and then easily let go once the demand subsided. This flexibility allowed companies to maintain a lean workforce while scaling up quickly when necessary.

Another significant factor was the cost savings associated with contractual labor. Permanent employees were costly, not only due to their higher wages but also because of the additional benefits and protections they were entitled to. Companies that relied heavily on permanent staff had to account for these ongoing expenses, which could erode profit margins. In contrast, contracted workers were typically paid less and did not receive the same benefits, making them a more economical choice for companies looking to maximize profitability.

As companies recognized the financial advantages, many devised strategies to keep the majority of their workforce on a contractual basis. Some even resorted to hiring workers for just 89 days, cleverly circumventing labor laws that would have required them to classify these workers as permanent if they worked 90 days or more. This practice allowed companies to exploit the benefits of a flexible, low-cost workforce without the financial commitments associated with permanent employment.

Thus, contractual labor was initially embraced for its ability to provide companies with the dual benefits of operational flexibility and cost efficiency. However, this system also perpetuated inequality within the workforce, as contracted workers remained vulnerable to exploitation, with fewer rights and protections compared to their permanent counterparts.

In Pakistan’s auto sector, the gleaming new cars rolling off assembly lines tell only part of the story. Behind the scenes, a vast army of blue-collar work -

ers powers this industry, many of whom are contracted through third-party agencies. Estimates suggest that around 1.8 million people are directly employed in car assembly, with this number swelling to 3.5 million when considering ancillary production.

In terms of the profile of the labour, the blue-collar workers in the industry typically have 10 to 14 years of schooling and recruitment is done through apprenticeships. These apprenticeships are done at a monthly stipend less than the minimum wage and are covered by the Apprenticeship Ordinance of 1962. Once these workers are made permanent, their wages can vary between Rs 16,000 to Rs 45,000. When the same figures are seen for contracted workforce, it is evident that they get lower wages and no benefits.

The auto sector’s reliance on contracted labour is well-documented. Typically, 20% of the workforce in this industry is hired on a contractual basis, with the remaining 80% being permanent employees. These contracted workers often receive lower wages and lack the benefits—like retirement benefits, overtime pay, and insurance—that their permanent counterparts take for granted.

In recent years, the sector has faced significant challenges, particularly after the government imposed a ban on imports in 2022 to conserve foreign exchange reserves. This, coupled with a steep depreciation of the rupee and soaring inflation, pushed up production costs, driving car prices higher and dampening demand. As a result, companies were forced to shutter production lines for weeks, even months.

To assess the impact of the Supreme Court’s ruling on the auto sector, let us examine two of the industry’s heavyweights: Pak Suzuki and Honda Atlas Cars. Both companies have disclosed their use of contracted labour, making them prime candidates for analysis.

In 2017 and 2018, Pak Suzuki’s production capacity stood at 150,000 cars and 44,000 motorcycles annually. As production ramped up, so too did the number of employees, rising from 1,345 in 2017 to 2,024 in 2018. However, the company did not specify how many of these workers were permanent versus contracted. Financial data, though, offers some clues. In 2017, outsourced labour costs were Rs958 million, increasing to Rs1,060 million in 2018.

Meanwhile, salaries and benefits for permanent employees grew from Rs1.3

billion to Rs1.8 billion. These figures suggest that the reliance on contracted labour as a percentage of total labour costs actually decreased slightly after the Supreme Court’s ruling.

Fast forward to 2023, and Pak Suzuki’s situation had deteriorated significantly. Production fell by 68% for cars and 64% for motorcycles compared to 2018 levels, largely due to plant shutdowns and dwindling demand. Despite this, the company maintained a relatively stable headcount, suggesting that it leaned more on its permanent workforce during tough times. Outsourced labour costs dropped to Rs758 million in 2023, while salaries and wages for permanent employees rose to Rs2.9 billion, indicating that contracted workers bore the brunt of the cutbacks.

Honda Atlas Cars presents a similar story. In 2017, the company produced 34,500 cars, ramping up to over 50,000 in 2018. Employee numbers rose accordingly, but like Pak Suzuki, Honda did not distinguish between permanent and contracted workers in its disclosures. Labour-related expenses increased from Rs1 billion in 2017 to Rs1.3 billion in 2018. By 2023, however, the company had slashed its workforce by a third, in line with a significant drop in production, yet overall wage expenses remained steady—a strong indicator that contracted workers were the first to be let go.

The data from Pak Suzuki and Honda Cars suggests that despite the Supreme Court’s efforts to level the playing field, contracted labour remains a vulnerable segment of the workforce. When economic conditions sour, these workers are often the first to face the axe, while permanent employees enjoy greater job security. The ruling may have ensured equal treatment on paper, but in practice, contracted workers continue to serve as the industry’s first line of defense against economic downturns.

As Pakistan’s auto sector grapples with an uncertain future, the fate of its contracted workers hangs in the balance. While the Supreme Court ruling was a step towards greater equality, its impact on the ground remains uneven. For now, the seths may have adjusted their strategies, but the fundamental disparities between permanent and contracted workers persist. In an industry where flexibility and cost savings often trump workers’ rights, the road to true equality may still be a long one. n

Pharmaceutical company’s biotech subsidiary to launch the new product in one of Pakistan’s biggest therapeutic areas

In a move that may have lasting reverberations in Pakistan’s pharmaceutical industry, Ferozons’ Laboratories’ subsidiary BF Biosciences has successfully launched its first human insulin drug under the brand name Ferulin. This drug is the first biosimilar to be launched in Pakistan that addresses diabetes, one of the most prevalent diseases in Pakistan.

Human insulin is a synthetic form of insulin produced in laboratories to mimic the natural insulin produced by the human body. It is used primarily to manage blood sugar levels in individuals with diabetes, particularly those with type 1 diabetes or advanced type 2 diabetes who do not produce sufficient insulin naturally.

Human insulin was developed in the 1960s and 1970s and was approved for pharmaceutical use in 1982. Before its development, insulin was typically derived from animal sources, such as pigs.

The primary advantage of human insulin over insulin analogs is cost, as it tends to be less expensive. However, human insulin may have a slower onset of action compared to some insulin analogs, which have been genetically modified to act more predictably and rapidly.

The introduction of Ferulin comes at a crucial time. Diabetes has become a pervasive health issue in Pakistan, with a staggering prevalence rate of 26.3% as of 2017. Ferozsons estimates that the number of adults living with diabetes in

Pakistan has surged to 33 million in 2023, an astonishing 70% increase since 2019. This dramatic rise positions Pakistan as the world’s third-highest country in diabetes prevalence.

Ferozsons, initially incorporated as a private limited company in 1954 and later transformed into a public limited company in 1960. It is part of the conglomerate that is perhaps best known for the Ferozsons publishing house, founded in 1894 by Maulvi Ferozuddin Khan, and the iconic bookstore on Lahore’s Mall Road. The publish-

ing house is best known for being the publishers of one of the definitive Urdu dictionaries, the Feroz-ul-Lughaat.

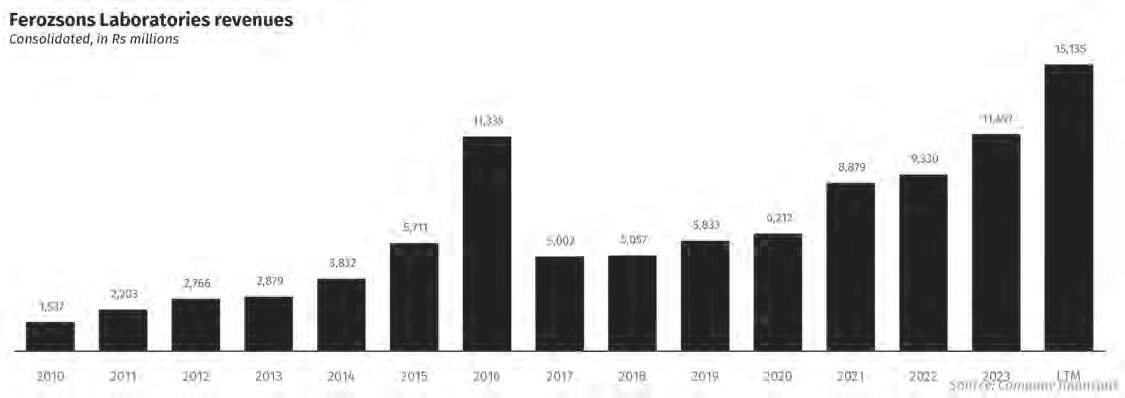

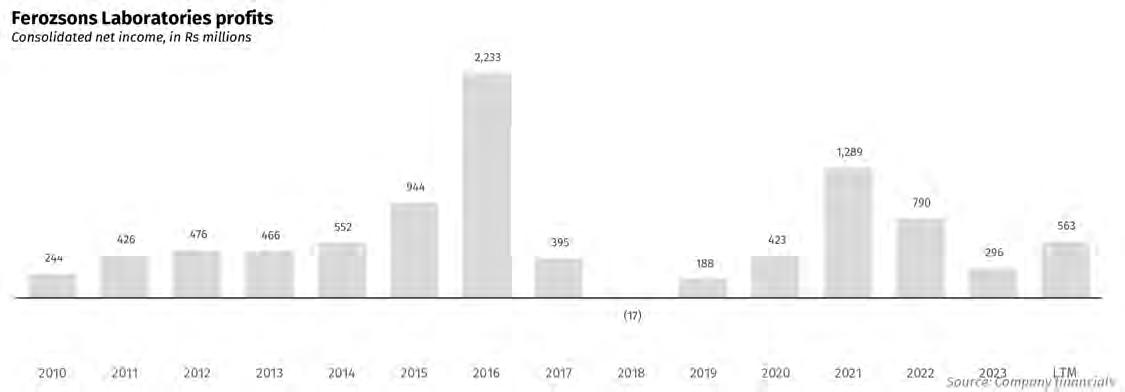

Ferozsons Laboratories has long been a mainstay in Pakistan’s pharmaceutical sector, though it first rose to prominence in 2014, when it partnered with Gilead Sciences of the United States to start producing and distributing Sovaldi and Harvoni, two drugs designed to cure Hepatitis C, in Pakistan.

Previous treatments for Hepatitis C only treated its symptoms and assumed it was a chronic disease a person had to live with. Sovaldi changed that, making it a curable disease.

Following the launch of Sovaldi in Pakistan just a few months after it first launched in the United States itself, Ferozsons made a killing: revenue swelled to a high of Rs11.3 billion in 2016, from Rs3.8 billion just two years earlier. While the increase in revenue from that drug did not last, the company is hoping that it can continue to rely on Gilead’s innovation pipeline to provide new products to Pakistanis who need them.

In 2020, for instance, the disease ravaging the whole world is Covid-19 and one of the most effective drugs against it is Remdesivir. Like in the case of Sovaldi, the partnership again is with Gilead Sciences for production of Remdesivir in Pakistan by Ferozsons.

In 2006, Ferozsons Laboratories entered into a joint venture with the Bagó Group of Argentina to establish BF Biosciences, Pakistan’s first biotech pharmaceutical company. Other international partners in the venture include BioGaia of Sweden, Nihon Kohden of Japan.

A biopharmaceutical, also known as a biological medical product, or biologic, is any pharmaceutical drug product manufactured in, extracted from, or semisynthesized from biological sources, as opposed to other drugs that are manufactured through a chemical process.

The first drug produced by BF Biosciences was Interferon, an antiviral drug used in the treatment of Hepatitis C. In 2003, Ferozsons

began importing Interferon, before launching the biotech subsidiary to begin the domestic manufacturing of the drug. Production started in 2009.

The country’s pharmaceutical market, valued at approximately Rs748 billion (US$2.7 billion) in 2023, has struggled to meet the growing demand for affordable and accessible diabetes treatments. Despite the high demand, the availability of insulin in Pakistan has been consistently below the World Health Organization’s (WHO) benchmarks, and affordability remains a significant hurdle for many patients.

For all the focus on innovation and bringing cutting edge products to the Pakistani market, Ferozsons barely cracks of the list of the top 25 pharmaceutical companies in the country, a list that tends to be dominated by the Pakistani subsidiaries of European and American pharmaceutical giants, or larger domestic manufacturers of generic medicines.

The drug launch also comes at an interesting time: on February 20, 2024, the government of Pakistan announced a new policy that would allow drugs not on the essential drugs list to have deregulated prices. Crucially for Ferozsons, most diabetes drugs, including insulin, are not on the list of essential drugs, meaning the company is free to set its prices for the drug, and to increase them without seeking government approval.

Historically, Pakistan’s drug pricing policies have been tightly controlled. The Drug Pricing Policy of 2018, which set maximum retail prices and linked price adjustments to the Consumer Price Index (CPI), exemplified this approach. The rationale was simple: safeguard public health by keeping essential medicines affordable. However, this well-intentioned regulation led to unintended consequences, including supply shortages and the exit of

major multinational pharmaceutical companies from the country.

The recent deregulation marks a significant shift. For the first time since the Drugs Act of 1976, pharmaceutical companies will have greater autonomy in setting prices for non-essential drugs. This decision, welcomed by the industry, is seen as a necessary correction to years of stifling regulation that left companies struggling with unsustainable profit margins amid rising production costs and a devaluing rupee.

Yet, the move has not been without controversy. Critics argue that deregulation could lead to skyrocketing prices, placing essential medicines out of reach for the average Pakistani. The Lahore High Court’s decision to stay the deregulation on February 22, 2024, was the predictable populist response to the deregulation. The stay order was then vacated on April 5, 2024.

The issue is emblematic of the broader challenges facing Pakistan’s pharmaceutical industry. The country’s reliance on imported raw materials, coupled with high inflation and currency devaluation, has squeezed profit margins to the point where companies are forced to either cut production or absorb losses. The case of Panadol—a widely used pain and fever reliever—illustrates this dilemma. Production was slashed, leading to widespread shortages, after GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare (GSKCH) struggled to secure a price increase in line with rising production costs.

The question now is whether deregulation will resolve these issues or exacerbate them. Proponents argue that by giving companies the ability to set prices, the industry will be able to maintain quality and ensure a steady supply of medicines. They point to the need for a balanced approach, where the Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan (DRAP) continues to monitor and regulate prices to prevent exploitation while allowing the market to function more freely. n

It is now possible for more than 80% of the people on the planet to visit Pakistan with a free e-visa, and for every citizen of the Gulf Arab states to visit Pakistan without a visa at all.

The policy, which had initially been announced last July by Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, went into effect on Independence Day this year and makes it possible for many more people to visit Pakistan than was previously possible. Citizens of the Gulf Arab states join the citizens of Nepal and the Maldives in being able to visit Pakistan without any visas at all.

In addition to the two member states of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), and all the member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), a third segment of people will also be allowed visas on arrival for Pakistan: Sikh pilgrims, who are not citizens of India, and who want to visit Sikh holy sites in Pakistan.

The move represents a continuity of policy between the otherwise fierce rivals in the currently ruling Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PML-N) and the party they deposed

from power, the Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaaf (PTI). It is almost entirely the result of desperation on the part of the government of Pakistan to earn foreign exchange revenue. The hope is that by making it easier for people to book travel to Pakistan, the government may be able to lure more foreign travelers – and their dollar-denominated spending power – to Pakistan.

At a press conference in Islamabad, Federal Minister of Information Attaullah Tarar elaborated on the details. The revised visa process, which went into effect last week, eliminates fees for electronic visas (e-Visas) for the selected 126 nations. The application process has been dramatically simplified, with the number of questions reduced from nearly 100 to just 30. For these countries, visas will be issued within 24 hours, granting a 90-day stay for both tourism and business purposes.

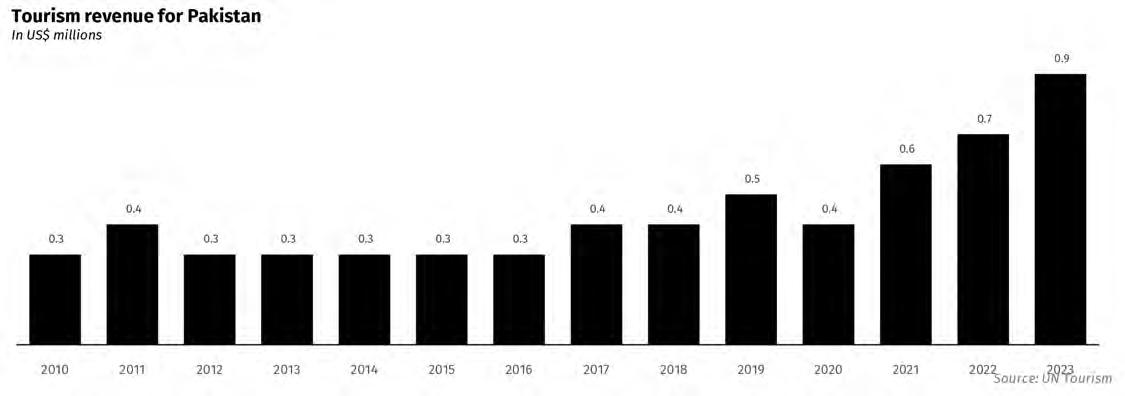

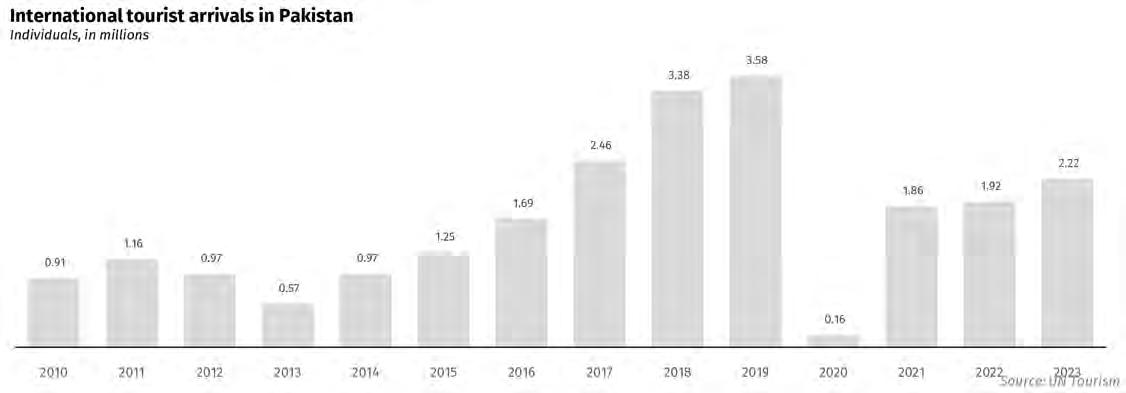

Pakistan has faced a sharp decline in the total number of tourists who visit the country. The peak for international tourism to Pakistan was 2019, when nearly 3.6 million foreign tourists visited Pakistan, according to data from the Pakistan Tourism Development Corpora-

tion (PTDC). It was that year that Pakistan began to appear in the video travelogues of American and European social media influencers and also began to be featured on lists such as Conde Nast Traveler magazine’s “The best holiday destinations for 2020” lists.

Of course, the year 2020 ended up being that of the coronavirus pandemic that resulted in worldwide lockdowns and the virtual collapse of international travel. Just 160,000 people visited Pakistan that year.

Following the end of the lockdowns, Pakistan’s international tourism began to recover and crossed the 2 million international arrivals mark in 2023, but has yet to come close to its peak of 2019. Indeed, it has yet to recover past the levels last seen in 2017.

The single biggest reason behind that apparent lack of recovery: the end of travel back and forth between Pakistan and Afghanistan by Afghan citizens, following the US withdrawal from Afghanistan and the government of Pakistan’s subsequent decision to expel nearly all Afghan citizens residing in Pakistan, including many who had lived in the country for nearly the entirety of their lives.

Excluding Afghan visitors, the 2019 peak for Pakistan was about 1.4 million tourists. While the 2023 and 2022 numbers do not yet have data broken out by country, for the year 2021, the total number of non-Afghan tourists to Pakistan was about 1.2 million, suggesting a sharp bounce back in the total number of high-spending tourists from the kind of wealthier countries that Pakistan wants to attract.

Pakistan is still a negligible proportion of the global tourism market that sees more than 1.3 billion people travel across borders to other countries for the purpose of tourism. And the nearly $1 billion that Pakistan received in foreign tourist spending in 2023 is negligible proportion of the nearly $1 trillion in total tourist spending.

The domestic tourism market, meanwhile, has taken off considerably. The total number of domestic tourists to Gilgit-Baltistan, for example, peaked in 2018 at 1.4 million travelers, which is more than 58 times the number of people who visited the province in 2007.

In 2021, for instance, when foreign travelers to Pakistan spent $852 million, domestic

tourists spent an estimated $8.6 billion – or more than 10 times as much as the foreign tourists – on domestic tourism, in what amounts to a cross subsidy of income between the relatively more economically prosperous parts of the country to the less prosperous, but more scenic parts of the country in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Gilgit-Baltistan.

In general, Pakistanis tend to like spending more on international tourism than international tourists like to spend in Pakistan. In 2023, when foreign tourists spent $0.9 billion in Pakistan, Pakistanis spent $2.2 billion abroad. The single largest recipient country of that tourist spending by Pakistanis was the United Arab Emirates.

The current policy of extending free, fast, e-visas to many countries in the world appears to not be connected to any expectation of reciprocity from those countries. Pakistani citizens currently have visa-free or e-visa access to 33 countries and territories. All 33 of those countries are

included in the list of countries to which Pakistan grants e-visa or visa-free access, so there is at least reciprocity with those countries.

Pakistanis have long been accustomed to reading our country’s name at the bottom of any compilation of a list of the world’s most power passports. According to a ranking compiled by Henley & Partners, a global immigration consulting firm, Pakistan ranks 100th out of 103 countries’ passports, fourth from the bottom in term of least access provided to its citizens by its passport. India ranks 82nd and offers its citizens visa-free access to 58 countries.

The government has made no indications that it intends to seek reciprocity from any other country, and perhaps just as well: the policy is designed to unilaterally make it easier for people from around the world to travel to Pakistan. To make it easier for Pakistanis to travel abroad is not a government policy, and even if it were, it would likely be subservient to the desire to attract more foreign visitors to Pakistan. It is highly unlikely that Islamabad would withhold visa-free access to the citizens of any country subject to reciprocity for Pakistani citizens’ access to that country.

Reduce burn, grow revenue, repeat. Software startup focused on the trucking industry has learned from the mistakes of others and is relying on its own cash flow for survival

By Nisma Riaz

“Winter is coming” goes the house motto of the Starks of Winterfell in the television series Game of Thrones based on the books by George RR Martin. In Pakistan, the fundraising winter is not just here, but likely to be a very, very long one, and the few startups still alive are the ones who have mentally adjusted to that reality.

One of those is Trukkr, the B2B software company focused on providing and enterprise resource planning (ERP) tool to the trucking industry in Pakistan. The company is now cash-flow positive, according to its founders, and is reliant mainly on its own internally generated cash flow for survival, recognizing the low likelihood of large sums of venture capital being made available to Pakistani startups any time soon.

Building a startup from scratch and getting it to cash flow breakeven is an impressive enough feat on its own, but what makes it more so is the fact that the company raised one of Pakistan’s largest seed rounds, announcing in March 2023 that they had raise $6.4 million

from leading investors like Accion Venture Lab and Sturgeon Capital.

The temptation to spend relatively large sums of money early in a start-up’s evolution can be quite high, and most Pakistani startups that were funded in the heady days of 2021 and 2022 have flamed out in large part because they spent very freely without having a game plan to reach financial sustainability within a reasonable time frame.

To borrow terminology from the startup accelerator Y Combinator, they were never “default alive”.

So how did Trukkr pull it off? Well, it helps that the business is run by a founding team that has a family history in the trucking business, and so had a running head start in knowing the challenges of the industry.

Co-founder Sheryar Bawany, who comes from a family with interests in the trucking business, identified a few major issues in the sector and set out to address them.

“The trucking industry in Pakistan has long suffered from a lack of digitization. Before founding Trukkr, I ran a trucking company for several years and noticed that everything relied

on outdated methods, like pencil and paper,” Bawany told Profit.

He explained how finding and arranging trucks was a time-consuming process, with companies spending hours on the phone trying to secure transportation. “This inefficiency was one of the main drivers behind developing a technology platform to streamline the process.”

“Another critical issue was the lack of visibility and transparency, leading to a significant trust deficit between truckers and companies. Businesses often had no idea where their cargo was or if it would be delivered on time,” he added.

Lastly, Bawany explained that the most pressing challenge was the working capital issue. Truckers faced upfront costs like fuel and maintenance, yet payments for services were delayed by months.

His solution was to build an ERP platform to help with the coordination of capacity and tracking of in-transit cargo, and then went one layer deeper but embedding fintech solutions within the platform to help bridge the working capital financing gap by offering lending solutions.

Trukkr is a two-sided market place, serving both trucking companies and the businesses that are their clients. Bawany

explains: “We serve two types of customers: truckers and companies. On the company side, businesses use our platform to source trips, manage their logistics, and track their loads in real-time. For truckers, we offer working capital loans to help them manage their business cash flows effectively.”

Two sided market places are a uniquely hard challenge in the tech world. You have to incentivize both the demand side by having enough buyers on the platform and the supply side by having enough sellers of whatever product or service you wish to build a marketplace for.

The simplest solution to this is just direct subsidies to both sides of the equation: offer high prices to sellers for their products and low prices to buyers, connect enough of them on your platform, and hope that people develop the habit of buying and selling on your platform before you run out of the money needed to keep subsidizing this business.

The Trukkr team, however, decided that they would take a different approach: relying on the convenience of the marketplace – and the availability of financing solutions for the sellers – to create their marketplace into a sustainable business.

In 2019, a team of four people got together to create technology that would address key industry challenges.

“While others were busy raising funds, we concentrated on building a comprehensive digital solution. By 2021, we were the first to launch a marketplace application for trucking in Pakistan,” said Bawany.

Although other companies followed, many offered only basic booking apps, Trukkr’s focus remained on developing a robust Transport Management System (TMS). “After five years of dedicated effort, I am confident that our TMS is the best in Pakistan, reflecting the extensive time and resources we invested in its development,” he shared with conviction.

But the question remains; how has Trukkr managed to survive in a climate that has caused even seasoned businessmen to quake in their boots?

The key is smart spending.

Trukkr raised $6.4 million in its seed round, and according to Bawany, nearly all of it has been allocated to developing the Trukkr platform.

“Unlike many competitors who focus heavily on operational expenditures, we believe in conserving resources and investing wisely. Burning money in operations, which some startups in our sector do, doesn’t yield the same benefits in Pakistan as it might in other countries with more established startup

infrastructure. Here, startups need to build their own infrastructure, making it crucial to avoid unnecessary spending.”

The company’s approach emphasises fiscal discipline and product development over excessive operational costs. “Our funding is used almost entirely — 90% — to enhance our platform. We are known for being extremely cost-conscious, to the point where even minor expenses, like printing extra pages, are scrutinised. This stringent cost management reflects our broader belief in applying traditional business principles to the startup world.”

In Pakistan’s business culture, younger people never have much money. Even among those hailing from industrialist families, the parents control the capital until they retire and their children are old enough to take over the business. What venture capital did was give a lot of money to very young people, who then ended up falling prey to the opulence and glamour that startups globally characterise.

Speaking on the matter, Bawany said, “I recall that during our journey, while many startups were spending heavily on flashy offices, stylish chairs, and bars, we often debated how much to invest in such amenities. As the youngest founder, I initially advocated for slightly better office environments and equipment. However, over time, it became increasingly clear that maintaining financial discipline and focusing on what truly matters was far more important than investing in non-essential luxuries.”

“We reject the notion that spending heavily is necessary for success or that a high top-line number is a true measure of progress. Instead, we focus on building a solid business foundation with sustainable unit economics. Having previously built a business, I’ve learned the importance of financial discipline, especially during challenging times. Our team shares this mindset, understanding the need to manage funds meticulously, even though the money is raised from venture capital. We treat every dollar with the same care as if it were our own, ensuring we build both the product and the necessary infrastructure effectively,” Bawany explained.

He added, “Many competitors of Trukkr in the logistics sector raised over $10 million in seed rounds and splurged extravagantly, which I find nonsensical.”

He agreed that in Pakistan’s nascent startup ecosystem, giving such large sums to young, inexperienced founders often leads to immaturity. “This first cycle of VC funding revealed that excessive early funding is not ideal, and investors are unlikely to repeat this mistake,” Bawany concluded.

They believe that this is the reason why while other companies were downsizing during the industry’s downturn, Trukkr’s

disciplined approach allowed them to continue hiring and expanding their team. “This made it easier to retain and attract top talent as other firms were laying off employees,” added Kasra Zunnaiyyer, another co-founder. When asked to share some hard lessons that he has learned from operating a business in an uncertain economy like Pakistan’s, Bawany said, “The key to success starts with the basics: honesty and realism. Be honest with your investors, as they support you through tough times. Our transparency about our situation, without exaggerating successes or downplaying challenges, helped us maintain their trust. Many rookie startups make the mistake of inflating their success during good times, which sets unrealistic expectations. When difficulties arise, this dishonesty backfires, leading to blame-shifting and excuses. Instead, be realistic and straightforward, especially when facing economic downturns. Additionally, manage your finances prudently—avoid overpaying yourself or spending extravagantly. Focus on building value and maintaining fiscal discipline, which is crucial in emerging markets like Pakistan.”

Another problem that many startups run into is chasing high valuations. Bawany says, “My view on valuation is somewhat unconventional. Often, we see billion-dollar companies plummet in value, revealing the unreliability of paper valuations. Valuation is crucial as it determines fundraising potential, but it’s important to recognize that valuations are negotiated, not demanded. In 2021, many startups received inflated valuations due to misrepresented numbers, with some startups valued at over $50 million despite being in their early stages. This unrealistic optimism has harmed the startup ecosystem in Pakistan, leading to lower valuations today. Instead of focusing on valuation, startups should prioritise profitability and solid business management. If a business demonstrates positive unit economics and growth, it will eventually receive a fair valuation, even if not immediately.”

While Trukkr is profitable, the founders like to call it being ‘financially sound’ and ‘avoids burning money’. “Unlike traditional businesses, startups must balance profitability with scaling. To grow, more resources are often required, which can reduce short-term profits. At Trukkr, most profits are reinvested to support expansion, finding a balance between profitability and growth,” Bawany expounded. When asked about Trukkr’s experience with fundraising after their last round, Bawany said, “Securing investment has become challenging as global investors are selective, particularly when macro conditions in Pakistan

aren’t favourable. In contrast to 2021, where investors actively sought opportunities, now you must be proactive in attracting interest. Despite this, Trukkr’s in-house developed platform, now reaching international markets, exemplifies Pakistan’s growing tech capabilities and competitiveness.”

Trukkr has recently launched operations in Bahrain and plans to expand further into the Middle East in the near future.

Speaking on expansion, Zunnaiyyer told Profit, “Our software, designed with a focus on product excellence, is tailored for international use, starting with Pakistan and expanding to other countries like Bahrain. Despite its Pakistani roots, it competes with billion-dollar companies. We continually enhance it to ensure customer acquisition and retention. Nearly 99% of our users remain engaged, integrating the platform into their daily operations, highlighting its value both in Pakistan and potentially abroad.”

How the Trukkr founding team came together is a story in itself. Three of the founders were schoolmates but there is one other, much younger member of the team who did not quite fit in.

Kasra Zunnaiyyer, a young boy obsessed with playing and building games, was a participant at Pro Battle, a CSS flagship competition at IBA, where he ended up meeting Mishal Adamjee, a sponsor of the event and now one of the founders of Trukkr.

Before becoming one of the youngest startup founders, Zunnaiyyer was a boxer in Lyari.

He told Profit, “My boxing career is deeply rooted in my father’s passion for the sport. He was a Pakistan champion for three years and was involved in various sports, but boxing was his main focus. From a young age, my brother and I were trained by him at home, almost daily.”

When he was in ninth grade, he joined a boxing club in Lyari, where he gained more formal experience. According to Zunnaiyyer, his height, reach, and early training made him a skilled boxer, however, it wasn’t long before he realised that while he had the technical ability, he did not quite possess the ferocity needed to excel in the sport. “I didn’t enjoy the idea of knocking people out, so despite my talent, I knew boxing wasn’t my true calling.”