15 18

15 18

08 The Jazz IPO is finally coming. What does it mean for the PSX?

15 From cotton yarn to cloud computing: Chakwal Spinning’s attempt at a turnaround?

18 Small textile mill closures accelerating in Faisalabad

20 Air Link to start assembling Acer laptops in Pakistan

26 In the first quarter after deregulation, pharma sector revenue up by 25%

28 Nawaz will spend Rs700 billion from the Punjab budget to be able to blame inflation on Shehbaz

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz Khan - Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Editorial Consultant: Ahtasam Ahmad - Business Reporters: Taimoor Hassan | Shahab Omer

Zain Naeem | Saneela Jawad | Nisma Riaz | Mariam Umar | Shahnawaz Ali | Ghulam Abbass

Ahmad Ahmadani | Aziz Buneri - Sub-Editor: Saddam Hussain - Video Producer: Talha Farooqi Director Marketing : Mudassir Alam - Regional Heads of Marketing: Agha Anwer (Khi) Kamal Rizvi (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) - Manager Subscriptions: Irfan Farooq Pakistan’s #1 business magazine - your go-to source for business, economic and financial news. Contact us: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

Nearly three decades after launching, Pakistan’s largest telecommunications company is about to list itself on the stock exchange. What is that likely to mean for investors?

By Hamza Aurangzeb

It is likely to be one of the biggest initial public offerings (IPOs) in the history of Pakistani capital markets, and certainly the most significant public listing since Habib Bank’s IPO in 2007: Pakistan Mobile Communications Ltd, the country’s largest telecommunications company and better known by their consumer-facing brand Jazz, is finally going public.

The news that Jazz is planning this IPO has been telegraphed clearly and publicly for weeks now, and some hints have been emanating from the company’s senior management for quite a few months before then. What makes it significant is that, while an IPO is typically a significant milestone in the history of a company, this particular IPO is likely a more significant development for Pakistan’s capital markets than it is for Jazz, the company ostensibly relying on those capital markets to raise funding.

In Pakistan, as in many frontier and emerging economies, many of the largest and most profitable businesses tend to be private, meaning that public market investors tend to not have the ability to invest in some of the most profitable and rapidly growing sectors of the economy.

Telecoms is one of the most prominent such sectors, because there has been strong growth in that sector, it is highly visible owing to its consumer-facing nature, and it is one of the largest and most important sectors in the economy, but until now, just one major telecom company – the state-owned Pakistan Telecommunications Ltd (PTCL) – has been publicly listed. (Worldcall, a cable internet provider, is listed, and Wateen, an internet infrastructure company, was previously listed While they are interesting companies, they are not of the same scale as the mobile telecommunications companies.)

Pakistan’s mobile network operator space has shrunk from five to three as a result of acquisitions. Warid was acquired by Jazz in November 2015, and Telenor Pakistan has been acquired by PTCL in December 2023. If this IPO goes through, we will enter a brave new world where two out of three mobile network operators will be publicly listed companies, with the only unlisted one being China Mobile Pakistan Ltd, known by its consumer brand name Zong.

This is, in more than one sense, a big deal.

In this story, we will take a look at the state of play in Pakistan’s mobile telecommunications industry and Jazz’s dominant role in it, the challenging unit economics of running a mobile provider in Pakistan, before looking at what this IPO will be

The story of Pakistan’s mobile industry begins in 1989, when the government first granted licences for mobile operators. Two companies won bids for that spectrum: Instaphone and Paktel, and both were able to launch service at almost exactly the same time in October 1990. Instaphone was a collaboration between the Swedish telecom company Millicom and the Arfeen Group (a Karachi-based trading and industrial conglomerate). And Paktel was a collaboration between the UK-based Cable & Wireless and the Hasan Group of Companies.

Both of these companies, however, operated at a time when per capita income in Pakistan was very low, and the global telecommunications industry too small to make a dent. Pakistan did not get a taste of a mass-market mobile company until Mobilink (now Jazz) finally launched its services in 1998. Mobilink was a joint venture of Motorola and the Saif Group (owned by the politically prominent Saifullah Khan family, originally from Lakki Marwat).

The advantage Mobilink had was timing: it came right as the cost of communications equipment (both mobile handsets as well as the infrastructure for the cellular towers) was beginning to drop enough to become a more mass-market product and Mobilink had the good sense to come in with GSM (Global System for Mobile Communications), the standard beginning to take over Europe and what would soon become the global standard for communications.

In 2000, Orascom Holdings of Egypt bought a controlling stake in Mobilink and began investing heavily in building the company into a truly national carrier rather than simply

one that focused on the major cities. Mobilink consistently had a greater than 50% market share during this period in Pakistan’s telecom history, both in terms of revenue as well as number of subscribers.

In 2001, more than a decade after the emergence of a Pakistani mobile industry, PTCL decided to enter the fray with Ufone and quickly began to take market share.

The pioneers in the industry – Paktel and Instaphone – continued to die a very painful death. Instaphone was bleeding itself into the grave because it continued to stick with Digital-AMPS technology even as GSM had become the dominant technology even in North America, the birthplace of AMPS. Paktel tried to save itself by converting to GSM in 2004, but it was too little too late.

Meanwhile, two new players had entered the industry. Telenor, the Norwegian telecom giant, launched its services in Pakistan in March 2005. And then came Warid, a new company that had the backing of the Abu Dhabi Group (owned by members of Abu Dhabi’s ruling Nahyan family), launched its services in Pakistan in June 2005.

By mid-2008, Telenor was the second largest provider and Ufone the third-largest. The year 2008 was also the year China Mobile officially launched the Zong brand in Pakistan. The company had bought a dominant 88.9% stake in Paktel a year earlier, in January 2007, for $284 million. China Mobile increased its stake to 100% by May of that year.

And thus began the era of the five mobile operators in Pakistan that continued for almost a full decade. Warid, being the smallest of the operators, was always struggling, and finally gave up in November 2015, selling itself to Mobilink, which then rebranded itself Jazz. And late last year, Telenor got fed up with the government of Pakistan’s restrictions on repatriation of profits and sold its operations

With five competitors slowly being whittled down to three, Pakistan’s mobile communications space is somewhat less competitive than it was on the surface, but given the fact that the three remaining competitors are now more financially viable, is perhaps even more competitive than before.

Jazz has been the dominant player in Pakistan’s mobile communications space and apart from briefly losing that crown to Telenor in 2015, has been the single largest company in the sector almost since its beginning in 1998. The company currently commands a 37.1% market share, which is still higher than the expected combined share of Ufone (estimated to be 36.6% of the market) once the merger of Telenor Pakistan (23.2% market share) and Ufone (13.4% share) is completed. Zong, currently number two at a 25.4% share, will then be the third largest company in a three-company market. The total market size of the telecom sector has expanded from Rs604 billion in fiscal year 2019 to Rs850.2 billion in 2023. And the total number of mobile cellular subscribers increased from 167 million to 197 million during that same period. Although these data points create a semblance of progress for the sector, the reality is quite different. The telecom market size did indeed expand by 40.7% in rupee terms, however, it declined by 20.7% in dollar terms during the period, despite the base of mobile cellular subscribers growing by 18%.

Beyond the obvious collapse in the rupee’s exchange rate against the dollar, there are more reasons why the telecoms industry has seen revenues stagnating.

Put simply, the industry is highly

competitive and offers a largely commoditised product, which means no player has the ability to substantially raise prices. This is mostly fine because even though the capital expenditure required just to maintain service levels is extremely high, the marginal cost of delivering services is near-zero, meaning providing mobile telecommunications is still a high margin business for a large enough player. It just means that cash flows remain stable, but do not actually grow, at least not after adjusting for the depreciation in the value of the rupee.

This is best illustrated with Jazz’s own financials (currently available owing to the fact that its holding company, Veon, is publicly listed in Amsterdam).

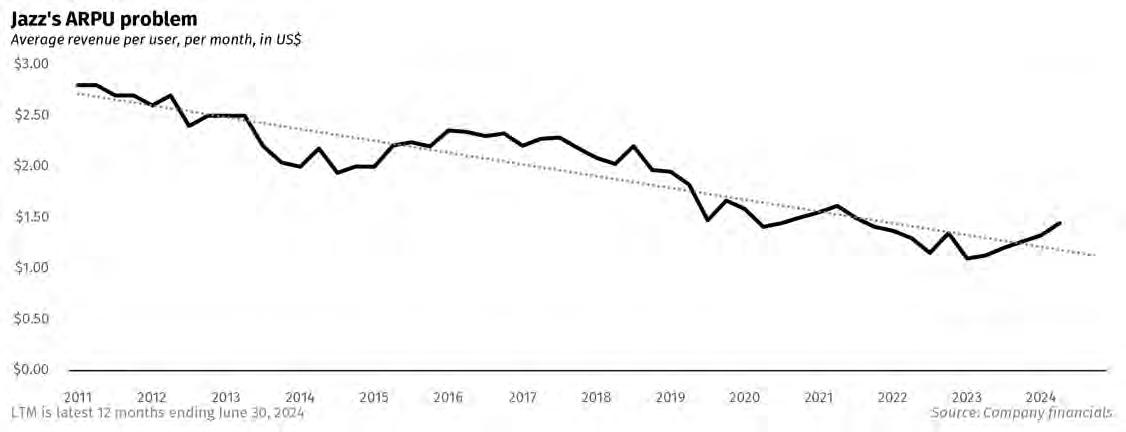

Between 2008 and the latest 12 months ending June 30, 2024, Jazz’s total revenues increased from $1,122 million to $1,233 million, an increase of just 7.9% over more than 15 years, or a meagre 0.5% per year on average. Between 2010 and 2024, the company’s number of subscribers increased by an average of 6.1% per year, but average revenue per user dropped in USD terms by an average of 5.7% per year, going from $2.83 per user per month in 2010 to just $1.31 per user per month in 2024, effectively erasing nearly all of the gains from its increasing subscriber base.

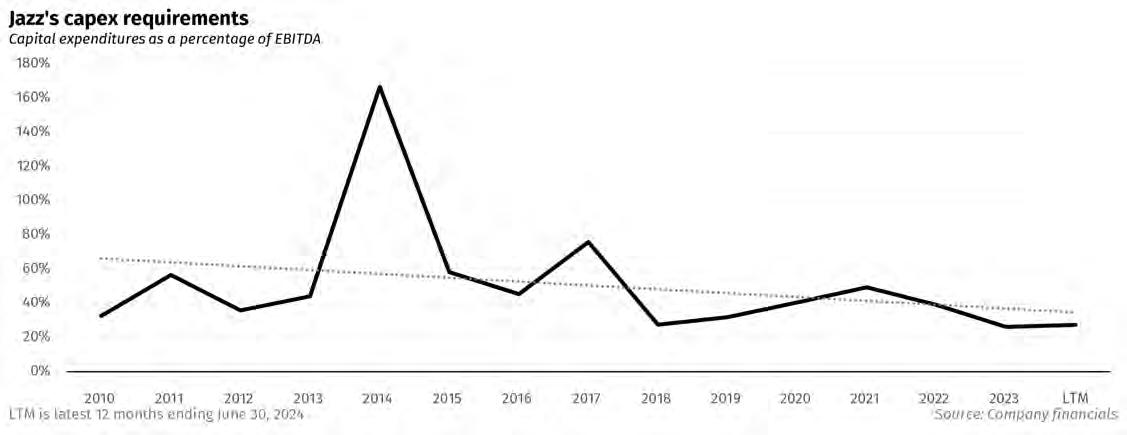

During that time, Jazz invested nearly $4 billion in capital expenditures to upgrade its infrastructure from 2G to 4G mobile broadband internet capability, which it now offers virtually all over the country, and buying the licenses from the government for the spectrum needed to offer those services. And that does not even include the acquisition price of Warid.

It might seem as though all that investment in infrastructure did not get Jazz much in terms of growth, but the way to think of that capex is that it is the cost of doing business in an industry that has a near-zero marginal cost of goods, and therefore high profitability

margins, which need to be partially spent on maintaining service levels, including investing in technology upgrades up to the latest level. Since 2010, Jazz has had an EBITDA margin that averaged 45.4% of total revenues. EBITDA stands for earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation, and EBITDA margin represents an estimate of the free cash flow generated by a business as a percentage of total revenue. That is a very healthy cash flow margin, and during that same period, Jazz has had to invest back about 43.4% of its EBITDA into capital expenditures, meaning its EBITDA margin net of capex has been 23.1% on average. Revenue is not be growing much in USD terms since it is operating in a highly competitive market that is nearing saturation levels where the marginal new customer has a low purchasing power. But profitability is remarkably steady. From an investor’s perspective, that means one can expect only minor capital gains, but likely a steady stream of dividends.

Jazz’s stagnant revenues are in line with the global telecommunications industry, and so is its response: trying to use its large base of internet-connected customers to offer more services that could add more growth to its top line. The company has branded its attempt to follow this strategy Digital Operator 1440 and it launched this strategy in 2021.

It has introduced several new apps such as Tamasha for entertainment, Garaj for cloud services, Simosa and Rox for lifestyle and account management, Bip for messaging services, Quantica which provides data generated insights to business customers, and Jazz Cash for financial services, which is its best-performing vertical apart from its core business. It

is also the furthest along, since it was launched more than a decade ago and while it has been bundled into this strategy, was originally conceived differently.

Further, to streamline service delivery, the telco has realigned its operational structure with each department dealing with distinct set of services and operating independently like a company of its own.

There are two main reasons why the company has finally decided to pull the trigger and go public now. The first has to do with considerations at its global parent company level, and the second has to do with its own domestic balance sheet.

The company’s global parent is Veon, the Netherlands-domiciled global telecommunications giant owned in large part by Russian shareholders. They have decided to “consolidate their footprint” across the markets they serve, which is corporate-speak for “they want to sell their assets and exit from some markets and redeploy the cash to markets they want to stay in”.

This does not mean, of course, that the company is planning on exiting Pakistan entirely, but it does want to reduce its shareholding in Pakistan and invest the money it gets for selling its shares in Jazz on other investments outside Pakistan.

Pakistani investors should not take this as a sign of anything beyond the idiosyncrasies of the company itself. Veon publicly announced on August 1, 2024, that it planned to delist itself voluntarily from Euronext Amsterdam. Furthermore, it also unveiled a share buyback program of up to $100 million for the American Depositary Shares.

There is then the related matter of the local balance sheet of Jazz itself. Veon wants

to reduce the dollar-denominated debt on its consolidated balance sheet, and add more nonUSD denominated debt.

Veon wants to bring its share of USD and Euro-denominated debt below 50% in conjunction with minimizing its leverage ratio below 1.5x and increasing the average maturity of its debt to more than 4 years by the end of 2027. As of now, the share of Group’s net debt (excluding leases) in USD stands at 57.6%, its leverage ratio remains 1.59x, while average tenor of its debt is 3.4 years.

Following suit, Veon’s subsidiary in Pakistan, Jazz, secured an extended long-term credit facility of Rs75 billion through a consortium of financial institutions led by the Bank of Punjab. The company aims to utilize this facility to realize its dream of emerging as a full-fledged services company. It aspires to expand its business in a variety of OTT services to optimize its risks through diversification and improve financial metrics like Revenue, EBITDA, and ARPU.

Now, although it makes sense to utilize debt to finance growth in new verticals as debt is cheaper than equity but nevertheless, Jazz’s debt has been increasing consistently over the past five years and that has elevated its debt-to-capital ratio to 53.0%. Jazz holds $771 million out of a total 2,227 million, which represents 34.6% of the total net debt of the group.

Thus, the company is pursuing an IPO to diversify its capital structure and optimize risks by persuading local investors to invest. This will not only assist Jazz in fulfilling the global vision of the group but also grant it greater discretion, enabling it to manage cash flows more efficiently and improve its financial metrics.

“In the case of Jazz, it appears that in addition to their stated reasons for IPO, they would like to reduce their risks as foreign investor in Pakistan by bringing in locals as investors. If local investors become shareholders in the company, it will not only inject fresh equity and diversify its capital structure but also reduce the risk of sudden policy changes

from the government or PTA, because a big number of local vocal investors in general and stock exchange in particular, will be adversely affected by any such change. After IPO, Jazz will be subjected to increased scrutiny, enhanced reporting and will be required to ensure transparency in its accounts and governance.” reiterated Aslam Hayat, ICT regulatory professional and former Chief Corporate Affairs an Strategy Officer of Telenor Pakistan.

“Jazz, as one of the largest private sector organizations in Pakistan, aims to deepen its integration into the local economy and contribute to the nation’s financial growth. The IPO aligns with Jazz’s strategy to transition from a traditional mobile telco to a dynamic ServiceCo. Moreover, it provides an opportunity for the local community and investors to participate in Jazz’s future, reflecting our confidence in Pakistan’s capital markets,” the telco responded to Profit’s queries.

According to Bloomberg, Veon aims to sell 20% stakes of Jazz, and its CEO is optimistic about the potential interest of local pension funds, institutional investors and even retail investors in the stakes of the country’s largest mobile network. While rationalizing the route of an IPO, the group has specifically appointed Farrukh Khan as the new CFO. Farrukh Khan is the former CEO of the Pakistan Stock Exchange, and prior to that, founded the investment bank BMA Capital, where he led the IPO of the state-owned Oil & Gas Development Corporation (OGDC) in 2005, then the largest IPO on the Pakistani capital markets.

IPOs are an uncommon occurrence in Pakistan, with no more than 3-4 a year, on average. There are more than 500 companies listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) that are

distributed among 38 sectors. However, their cumulative market capitalization represents a nominal sum of Rs10.2 Trillion ($36.7 billion). PSX is a market that even lags behind its peers like the Dhaka Stock Exchange (DSE) whose market cap is $60.3 billion, let alone the gigantic Bombay Stock Exchange in India, which is worth $5,500 billion, 150 times the size of PSX.

The largest ever equity offering on the PSX was actually not even an IPO, but the secondary public offering (share sale after an IPO), when the government sold its remaining shares in Habib Bank Ltd for Rs102.3 billion (then just over $1 billion) in 2015. The Habib Bank IPO in 2007 raised a little over $200 million.

By any measure, the Jazz IPO would likely be at least in the top five equity market transactions of all time in Pakistan, though it is unlikely to dethrone the secondary offering of HBL. Is this the right time to attempt such an ambitious transaction?

Perhaps. Pakistan’s inflation is decelerating and is expected to reach 9.5% by the end of August. Moreover, the central bank’s policy rate which stands at 19.5% today is projected to fall to 16% in the next six months, it may even go down to as much as 14% by the end of 2025 as per the analysis of Fitch Solutions.

The country’s economy has been recovering over the past three quarters displaying reasonable growth. Overall, Pakistan’s GDP grew by 2.4% during FY24 and is expected to grow at a rate of 3.5% during FY25, according to the IMF. In addition to that, MSCI recently incorporated seven companies into its indices, where six companies were included in the MSCI FM Small Cap Index, while one was added to the Frontier Market (FM) Index, which showcases the growing significance of Pakistani capital markets at the global stage.

“Jazz views this as a strategic move to showcase its long-term confidence in Pakistan’s

economic potential. The timing allows Jazz to attract investors who share a vision for sustained growth, even in challenging market conditions. In 2023, among global IPOs, the most capital was raised in the technology sector. By transforming into a ServiceCo, Jazz is well-positioned to attract investors who understand the future potential of digital technology and are willing to accept the associated risks. This step is part of our broader strategy to solidify Jazz’s role in emerging industries, reinforcing our commitment to innovation and growth,” the company added in its official response.

Let’s move on to the valuations, one of the most indispensable elements of an IPO. So, you must be wondering what is the worth of Jazz in the eyes of Pakistani investors. Maybe we could answer that, we have aggregated data for four indicators from three peer companies in the technology and communications segment of PSX to deduce a spectrum of valuations for Jazz.

These three companies include Pakistan Telecommunications Ltd. (PTCL), Telecard Ltd. (TELE), and Netsol Technologies Ltd. (NETSOL). The aggregate data of the group will serve as an adequate focal point to reference Jazz’s valuations. We evaluated these three companies across four multiple valuations which include

• Enterprise value to revenue (EV / Sales)

• Enterprise value to earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EV / EBITDA)

• Enterprise value to earnings before interest and taxes (EV / EBIT)

• Price to book value (P / B)

The lowest valuation was provided by the first method of EV/Sales, which was around Rs154.1 billion, where the average enterprise

value of the group was 1.085 times the revenue, while the highest valuation for the company was put forth by the EV/EBIT method. It indicated that the average enterprise value of the group was 7.688 times the earnings before interest and taxes and the market cap of the company was Rs456.6 billion. If Jazz gets publicly listed its actual value will lie somewhere between these two numbers, like Rs300 billion ($1.07 billion), it will most likely be one of the most valuable companies in PSX and the most valuable publicly listed tech company by afar.

(The calculations are based on publicly available data and we acknowledge that certain intricacies of the valuation process might lead to a different range than stated above)

In 2009, the stock market of Bangladesh along with stock markets of the globe plummeted to new lows, crushing the hopes of all the stakeholders involved in capital markets. However, all of them believed that a new entrant of adequate stature could provide the impetus needed for commencing a bullish trend in that gloomy landscape.

In comes Grameenphone, which enhanced the liquidity of the Bangladeshi market and allowed it to flourish, while making global headlines. It presented an opportunity of a lifetime to the general public in Bangladesh, enabling them to share in the profits of a national champion company. Its shares were offered at a rate of Tk70 apiece but now has climbed up to Tk377 with a market cap of Tk510 billion.

Jazz stands at the same crossroads where Grameenphone was in 2009, with the national economy along with capital markets underperforming and longing for a catalyst to reverse their fortunes. Jazz could be the catalyst that breaks the Pakistani capital markets out of their stupor. n

The textile mill located in Kasur wants to move from basic to high-tech, and may have found an investor to back it; can it pull off this comeback?

By Zain Naeem

By mid-2023, Chakwal Spinning Mills was a company seemingly on its last legs, its share price hovering at a mere Rs2.06 per share in trading on the Pakistan Stock Exchange. The business had been dormant since 2017, racking up losses, and its auditors had all but written it off as a lost cause. Yet, within a year, its stock skyrocketed to an eye-popping Rs156.33 — a 75-fold increase. What happened?

Chakwal Spinning Mills, a former textile stalwart, had been teetering on the brink of insolvency. With operations shuttered since 2017 and its factory leased to Yousuf Weaving Mills Ltd, the company was plagued by mounting debts and no revenue stream to speak of. By June 2023, it had accumulated losses of Rs893 million, pushing its equity deep into the red, at negative Rs125 million. The assets on its balance sheet, worth Rs737 million, were dwarfed by liabilities totaling Rs862 million, of which Rs567 million were short-term borrowings. The situation was so dire that auditors questioned its ability to continue as a going concern.

In an attempt to stave off complete collapse, the company pursued a reverse merger which went nowhere. It then tried stopgap measures, including allowing its premises to be rented out to other companies in a desperate

bid for revenue generation. Yet by March 2020, even this modest income had dried up, and the company was left with nothing but a grim outlook.

Fast forward to December 2023, and the company announced that it had revalued its property, plant, and equipment, transforming its negative equity into a positive figure. It also signed a memorandum of understanding with an IT firm, sparking hopes of a turnaround. New auditors lifted their qualified opinion, and rumours swirled about a potential debt restructuring deal with its banks.

In July 2024, the company officially rebranded itself as Quantum Cloud & AI Technologies Ltd, reflecting its new direction and ambitions. By then, the stock had already begun its ascent, rising from Rs2.06 in November 2023 to Rs 50.31 by July 2024 — a staggering 25-fold increase. But the market was not done yet. After the name change and the introduction of a new ticker symbol, “CLOUD,” the stock hit Rs156.33 in August 2024, leaving analysts scratching their heads.

The company’s official explanation came only on August 19, 2024, when it disclosed a Rs7.8 billion deal with PNO Capital to launch a data centre and cloud operations in Pakistan. The deal included a Rs 0.5 billion equity injection and a Rs7.3 billion convertible bond, set to fuel the company’s new ventures and pay down some of its debt.

But the timing of the stock surge, long before this news became public, raises serious questions. The stock exchange had repeatedly

inquired about the unexplained price rise, yet no major developments were disclosed. Now, with the stock price having ballooned 75 times over the past year, speculation is rife that insider information may have leaked, or that the price was artificially pumped, creating a speculative bubble.

Is Quantum Cloud & AI Technologies Limited truly poised for a dramatic turnaround, or is the market riding high on nothing more than hot air? The company’s future—and the legitimacy of its stock surge—remains shrouded in uncertainty. And while we are on the subject, who exactly is PNO Capital, and can they really back this company with Rs7.8 billion in capital?

Chakwal Spinning got its start in 1988 in textile spinning, which is the business of converting ginned cotton into cotton yarn. It relies on machines that are only marginally more sophisticated than the spinning jenny, invented in 1764 by James Hargreaves, an English weaver and carpenter, in Stan hill, Oswaldtwistle, Lancashire in England.

The company was one of the many unremarkable textile spinning mills in Pakistan, manufacturing a basic product out of its factory in Kasur, for much of the two and a half decades after its founding. Its revenues peaked in 2013 at Rs2.7 billion. Thereafter, things

began to go wrong, with a precipitous collapse in revenue that went to completely zero in financial year 2021, and the company has not recovered since. The last year of profitability was 2014, following which the company has spilled a sea of red ink.

Meanwhile, a significant question in understanding what is going on is: who is PNO Capital? A look at their LinkedIn page and website show that they are a firm that claims to be a middle market private equity firm based out of a small office in Khadda Market, a commercial area in DHA, in Karachi, generally not the kind of place a company that can command billions of rupees in capital tends to locate their offices.

Their website lists three portfolio companies, one of which they state they exited in 2021, which was a 50 megawatt wind farm in Gharo, Sindh. This is the only investment that can fairly be described as “middle market”. The other two include a bus company that

owns 100 buses that run between Lahore and Multan, and a company that owns a motor racing track.

The firm is owned by one person: Jawad Amjad, a 1992 graduate of the MBA program at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS). Mr Amjad is also the majority owner in Optimus Capital Management, a securities brokerage firm that also has a small investment banking arm.

Could this firm have access to enough capital to invest Rs7.8 billion into Chakwal Spinning? Yes, but the odds seem a bit stretched.

Could a firm that struggled to operate a textile spinning factory for over a decade transform itself into a large cloud computing company? Possibly, but one would likely be highly sceptical of the endeavour.

More likely, though, it seems that the

pivot towards cloud computing is somewhat aspirational. Every year, someone decides to buy a defunct company that still has its listing on the Pakistan Stock Exchange and turn it into a backdoor public listing and capital raising opportunity for a new venture. More often than not, those attempts end up not succeeding.

It is not possible to say definitively as to whether or not this attempt will succeed or fail. We can state, however, that the kind of details one normally expects to find in a corporate restructuring with strong odds of success – detailed business plans, profiles of new investors, perhaps new management hires, etc. – are absent in this case.

A strong run up in the stock price right before a major disclosure that seems hastily put-together smells more like a “pump and dump” scheme, an uncharitable theory made a bit more likely by the fact that the investor named is one who also happens to be the majority of a brokerage firm, which is certainly helpful if one ever wanted to run a “pump and dump” scheme. n

By Shahab Omer

It is one of Pakistan’s biggest crybaby lobbies, constantly asking for free goodies, which means that there is generally very little sympathy amongst the public for the textile industry. But while the larger players tend to be rich and have the capacity to withstand much tougher economic conditions, smaller textile mills have always had a harder time, and in recent years, many have been struggling to keep their doors open.

The industry has a penchant for hyperbole, so Chaudhry Salamat, a key voice in the Pakistan Hosiery Manufacturers and Exporters Association, issuing a warning that the entire industry in Faisalabad could shut down should be taken with a bucket full of salt. Such fears are nearly always just scare tactics from an industry used to public largesse and throwing a fit when it gets anything less than everything it asked for.

But this time, the rumours were lent slightly more credence by the news that Sitara Textile, one of Pakistan’s largest and most storied mills, was shutting down. The company’s CEO, Muhammad Idris, quickly dispelled these claims, though he confirmed that operations had indeed been halted—not as a final closure, but as part of a strategic relocation.

Idris explained that the mill’s closure was a response to the unsustainable cost of doing business in its current setup. The plan, he said, is to move operations to the Faisalabad Industrial Estate Development and Management Company (FIEDMC) where the company has already secured land. This move, he argued, is about modernizing the business, slashing costs, and integrating new technologies—not giving up.

In particular, many of Faisalabad’s older mills have been relocating owing to a shift in Faisalabad’s urban geography: many of the mills were on land that is increasingly more valuable as middle class housing rather than industrial plants, and hence many mills have found themselves able to finance a move – and pocket a considerable amount of capital – by selling their land to real estate developers (or developing it themselves), and buying cheaper land on what are now the outskirts of Faisalabad.

Far from being a sign of bad times, this may reflect a rising prosperity in Faisalabad, and creating the opportunity to unlock value from fully depreciated assets on corporate balance sheets.

But many in the industry are less optimistic. Conversations with industry insiders reveal

deep-seated frustration with what they see as the government’s neglect of a sector that is vital to the nation’s economy. While larger players might have the financial muscle to weather these storms, smaller mills are hanging by a thread.

The past five years have been a rollercoaster for Pakistan’s textile sector.

After a downturn in fiscal year ending June 30, 2020, when exports slumped to $12.53 billion — a 6% drop from the previous year — industry hopes were briefly revived. The government, facing a global economic slowdown and the early tremors of the COVID-19 pandemic, had opted to keep energy prices low for key export sectors like textiles, hoping to stave off disaster.

This strategy paid off in the short term. By fiscal year 2021, textile exports had rebounded to $15.4 billion, a 25.5% increase. But this resurgence came at a cost. The subsidies that kept the industry afloat added to the government’s growing fiscal deficit, and as international lenders like the IMF pressed for austerity, Islamabad had little choice but to raise energy prices.

The effects were immediate. By the fiscal year 2022, textile exports had surged again to $19.3 billion, driven by a global demand boom. Yet, as the government began rolling back subsidies, the industry’s future looked increasingly uncertain. Electricity rates, which had been hiked to meet IMF conditions, skyrocketed from Rs18-22 per kilowatt-hour to nearly Rs43.07 per kWh by mid-2024. Gas prices followed suit, particularly in Punjab and Sindh, where rates have climbed to $10.847 and $9.739 per mmBtu respectively.

As if rising energy costs were not enough, the industry has also been grappling with a long-standing issue: delayed tax refunds. Even during periods of relative government support, refund payments have been notoriously sluggish. This problem worsened under the Imran Khan Administration in fiscal year 2020, when delays in sales tax, duty drawbacks, and income tax refunds became a major source of frustration.

Although the government made efforts to clear backlogs in subsequent years — releasing substantial payments under schemes like the Duty Drawback of Taxes (DDT) and the Technology Upgradation Fund (TUF) — the relief was temporary. By fiscal 2023, refund delays were again choking the industry’s cash

flow, undermining financial stability and leaving many mills unable to meet payroll or cover operational costs.

This year, the government made a bold move, releasing Rs65 billion to clear pending refunds, covering all verified claims up until March 3, 2024. Yet, even this massive payout left Rs250 billion in refunds still outstanding, keeping the sector under significant strain.

Compounding these challenges are the fluctuating interest rates. In fiscal 2020, the benchmark interest rate stood at 13.25%, driven by the State Bank of Pakistan’s efforts to control inflation. Rates briefly dipped to 7% in fiscal 2021, offering the industry some breathing room, but have since climbed back to between 17% and 19%.

For an industry heavily reliant on working capital loans, these interest rate hikes have been difficult to deal with. Textile companies, already squeezed by rising energy costs and delayed refunds, are now facing prohibitive borrowing costs. The high markup rates discourage investment in new projects or expansion, further stifling growth and innovation in a sector that desperately needs both.

As competitors like Bangladesh and Vietnam benefit from lower borrowing costs and government subsidies, Pakistan’s textile mills claim that they are finding it harder and harder to compete on the global stage.

Over the past five years, the sector has seen a disturbing trend: the closure of nearly 100 mills a year on average, taking the total number of closed textile factories to nearly 1,600 mills.

While the big players might survive, smaller mills — unable to absorb the rising costs — are shutting down at an alarming rate. For these smaller operations, energy costs account for a significant portion of production expenses. With electricity and gas prices continuing to climb, many have no choice but to cut jobs, reduce output, or close their doors entirely.

The government now faces a critical choice: either step in to support this vital sector or let it collapse, taking thousands of jobs with it. For many in the industry, the outlook is bleak. If conditions do not improve, Pakistan’s textile sector — a once-strong pillar of the economy — could soon be reduced to a shadow of its former self. n

Mobile phone assembler and distributer moving into higher value electronics by setting up Pakistan’s second laptop assembler

By Farooq Tirmizi

It could be nothing, or it could be the start of something.

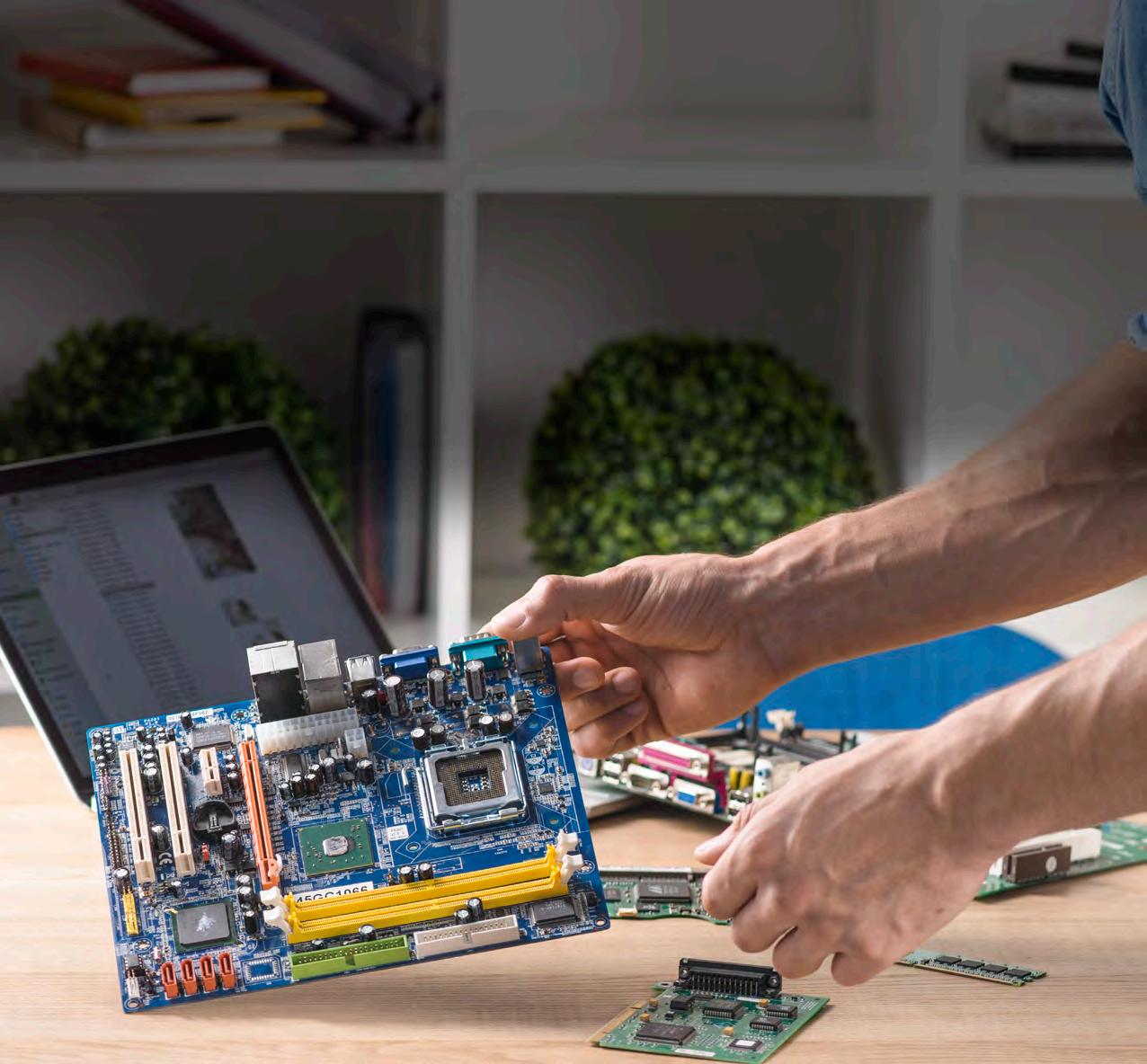

Air Link Communication, the Lahore-based retailer, distributor, and assembler of Chinese cellphones in Pakistan, announced last week that it had entered a partnership to start assembling

Acer laptops within the next year.

The agreement was signed with Acer Gadget Inc., a subsidiary of the Taiwanese tech giant Acer Inc., to assemble and distribute Acer’s latest lineup of laptops, tablets, and all-in-one devices in Pakistan. Acer is the fifth largest computer manufacturer in the world, with a 6% global market share, according to data compiled by data firm Canalys.

The partnership, officially announced

in a notice to the Pakistan Stock Exchange, grants Airlink exclusive rights to assemble Acer’s products at its state-of-the-art facility in Lahore. Airlink’s management is optimistic, projecting monthly sales of 10,000 units with an annual revenue target ranging between Rs15-20 billion. Production is set to kick off in the second quarter of 2025, with a focus on laptops initially, before expanding into tablets. This is, on the surface, a very big deal. It

is not the first time a Pakistani company has started assembling laptops inside the country. Haier Pakistan has a small laptop assembly business based out of its plant in Lahore as well. But come one, when was the last time you heard of someone buying a Haier laptop? Acer, on the other hand, is one of the biggest names in the business worldwide. If Acer laptops start getting assembled in Pakistan, that has to mean something significant, right?

Maybe, maybe not.

It is tempting to think of this development as being similar to the launch of the electronics manufacturing capabilities of East Asian companies, including Acer itself, which originally started off as an importer of Japanese and American electronics (like Air Link), before moving into assembling those products (like Air Link) before eventually developing complex manufacturing capabilities originally made available for contract for foreign brands before eventually launching its own global brands.

Those last two steps have not happened yet in Pakistan, quite obviously, and this would only be a big deal if there was a clear pathway towards eventually having a similar trajectory. Otherwise, it’s all very nice for Air Link shareholders, but would likely have limited impact on the Pakistani economy. After all, Pakistan has been assembling Toyota, Honda, and Suzuki automobiles inside the country for decades, and it has not translated into a large domestic car manufacturing industry, certainly not one that is not reliant almost entirely on imported parts for the most complex components.

So, what will this development mean for Air Link, and what will it mean for Pakistan’s nascent electronics assembly and perhaps eventual manufacturing sector? And how will we know which direction this will take?

We explore the answers to those questions in this article. But first, a bit of context about Air Link, what it currently does, and

what it is setting about to build in the future.

Air Link began as a company that one might not even have noticed, not even incorporated as an entity when it started operations in 2010, instead being organized as an Association of Persons. Its business initially was imported and distributing mobile cellphones in Pakistan, taking advantage of a conducive regulatory environment that allowed the tax-free import of cellphones, as the government was keen to encourage the adoption of mobile telephones by the wider population.

It quickly expanded from just cellphones into the import and sale of laptops and tablets as well, eventually growing to a point where it decided to incorporate itself formally in 2014. In 2019, as the company continued to grow its revenue, it expanded into smartphone assembly, initially signing on to assemble Android phones made by the Chinese manufacturer Tecno, and then in 2022, started assembling phones from Xiaomi.

That locally assembled phones business is starting to become highly significant already, both for Air Link, and for the Pakistani market. For Air Link, it constitutes about 70% of its total revenues, and gives it a market share of between 30-40% among domestically assembled smartphones. Xiaomi and Tecno have rapidly climbed the ranks in Pakistan’s smartphone market, with Xiaomi now the fifth-largest brand and Tecno the fourth among locally assembled phones.

In aggregate, Air Link now accounts for approximately 6% of all cellphones sold in Pakistan, according to an analysis conducted by Sunny Kumar, an equity research analyst at Topline Securities, an investment bank.

But Air Link’s rise – and the growth of smartphone use and eventually domestic

assembly in Pakistan – would not have been possible without the specific economic and regulatory context that was created to enable it.

Like most countries in Asia, smartphone penetration rates have been rising in Pakistan. About 56% of the population has a broadband internet connection that they access through their mobile phone, implying that they have a smartphone.

According to data from the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA), annual mobile phone demand is rising by 6% per year for the past decade, with a particular surge expected this year. Total sales are expected to reach 33 million units in 2024, up from 22.9 million in 2023, which was a uniquely bad year as a combination of a sharply depreciating rupee, high inflation, and government-imposed import bans all conspired to severely limit the sale of new mobile phones in the country.

The year 2024 is therefore one of recovery, and the expected surge in demand comes despite the recent imposition of an 18% sales tax on mobile phones in the federal budget for the fiscal year ending June 30, 2025.

In this, as in many things, Pakistan’s core advantage is demographics: the median age in the country is 21, and in urban areas at least, youth literacy rates are very high, as much as 90% in some metropolitan areas, meaning that the largest cohort of Pakistan is just now aging into becoming part of the workforce, is literate, more likely to be urban than the past, and is more technologically savvy than its parents, creating the demand for a smartphone.

All of Pakistan practically lives on WhatsApp (odds are very high you are reading this article as a result of someone sharing it on WhatsApp); but even beyond that, there

are now many domestic technology services that have become a part of everyday life, with InDrive, Careem, and Bykea for transportation, FoodPanda for delivery, Daraz for e-commerce, the one-third of the Pakistani population that is currently between the ages of 20 and 40, earning an income and literate enough to be able to use smartphones, is fully engaged and online, and needs a smartphone to function.

How do we know the market for cellphones is driven by the demand for internet-enabled services? Because sales of cellphones in Pakistan peaked in 2020, at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, when 38 million phones were sold as more and more Pakistanis had to rely on the internet to get things done.

Demand pull factors explain why cellphone sales are rising. But that does not explain the rise of cellphone assembly and domestic supply. For that, one needs to understand the sea change that has taken place in the country in the past four years, driven largely by government policy.

As recently as 2016, just 1% of the cellphones sold in Pakistan were assembled inside the country, but in the first seven months of 2024, almost 95% of all cellphones sold in the country were assembled domestically. And locally assembled phones are increasingly more likely to be smartphones. According to the PTA’s data, in 2019, only 1% of domestically assembled phones were smartphones, a number that rose to 62% during the first seven months of 2024.

“We believe the increase in local assembly/manufacturing will lead to increased market competition, which will ultimately translate into competitive and affordable prices,” wrote Sunny Kumar, the research analyst at Topline, in a note issued to clients earlier

this month. “That said increased supply of low cost smart phones will further shift customer preferences from feature phones to smart phones.”

How did this happen? Two independent policies, both implemented by the Imran Khan Administration converged. Firstly, the Device Identification Registration and Blocking System (DIRBS) policy, introduced in late 2018, by the PTA ensured that government tax policy on cellphones was actually implemented beginning in January 2019.

This was a policy that meant that the government could block any cellphone on which taxes had not been paid from operating on mobile networks in the country, effectively rendering them useless unless the tax on them was paid. Smuggling was actively disincentivised.

And secondly, the 2020 Mobile Device Manufacturing Policy introduced a set of incentives to boost domestic assembly of cellphones.

The policy slashes regulatory duties for CKD (Completely Knocked Down) and SKD (Semi Knocked Down) manufacturing by PTA-approved manufacturers operating under approved quotas. This means lower costs for those assembling phones locally.

The fixed income tax has been axed for devices priced up to $350. For mid-range devices ($351-$500), the tax increase is modest, while high-end devices (over $500) see a more significant bump. Sales tax on CKD/SKD manufacturing? Gone. And locally assembled phones will be exempt from the 4% withholding tax on domestic sales, giving them a price advantage on home turf.

All of this serves to ensure that it is easier for Pakistani cellphone assemblers to serve the local market, protected through favourable tax regimes. The structure of the taxes helps Pakistani assembled phones – which are otherwise of somewhat lower quality – to be able to compete against foreign products.

Topline estimates that, based on the latest changes to the tax code implemented in the 2025 federal budget, the tax protection is highest for phones priced between $100-200 (Rs27,800 to Rs55,600), where the tax creates a 32% price difference. The average protection comes out to 18% on phones priced below $100 and even lower, at 11%, on phones priced at $700 (Rs194,600) or higher. Conversely, it is about 7% cheaper to import a phone priced at $30 (Rs8,340) or less compared to buying a locally assembled one in the same price range.

Air Link assembled about 1.2 million cellphones in Pakistan in 2022, and had revenues of about Rs98.1 billion during the 12 months ending on March 31, 2024, the latest period for which financial statements are available. That represents a massive three-fold increase over the Rs32 billion in revenue it earned during the preceding 12 months, though that was admittedly a time of considerable disruption in the company’s normal course of business as it faced the brunt of the government’s import bans that prevented it from importing supplies and fully assembled phones.

Yet, despite the fact that it is utilising only a fraction of its 3.2 million units smartphone assembling capacity, the company appears bent on continuing its expansion, both into laptops as well as the production of smart television sets.

Airlink is set to launch Xiaomi Smart TVs in Pakistan, tapping into the country’s growing demand for smart home devices. The smart TV market, currently dominated by brands like TCL, Haier, and Samsung, is estimated to reach 1.2 million units by 2025, according to estimates by Topline Securities.

Airlink’s entry into this market is a strategic move, with the company planning to assemble and distribute Xiaomi Smart TVs at a slightly lower price point than its competitors.

The plant for Xiaomi Smart TVs has already been set up in Lahore, with production expected to begin in the second quarter of 2025. Airlink aims to sell 45,000 units in the first year, with capacity utilisation projected to increase from 15% in 2025 to 30% by 2028, according to Topline’s estimates. This venture is expected to contribute Rs7 billion to Airlink’s revenue by 2025, with a compound annual growth rate of 39% over the next three years.

On the laptop front, the company aims to sell 120,000 units in the Rs125,000 to Rs175,000 price range, which could result in around Rs15-20 billion in annual revenue in the first year.

Pakistan’s laptop market, estimated at around 400,000 to 500,000 units annually, though this represents a sharp slowdown from the nearly 900,000 units the country imported during fiscal year 2022, according to data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS).

The industry has so far relied heavily on imports. According to Airlink’s management, local production of these devices could not only boost its market share in this large and growing market but also position the company to secure lucrative contracts with federal and provincial governments for their laptop distribution schemes for students.

In terms of profitability, despite the price protections afforded by the tax regime, Air Link operates on relatively low single-digit gross and net margins.

So is this rapidly growing, clearly ambitious company the start of something new in Pakistan? Are we going to see the rise of domestic electronics manufacturing that eventually develops into a globally competitive industry?

Or is this going to end up more like the auto industry, where what was supposed to have been temporary tariff protection ends up

becoming a permanent lobby for an industry that is grossly uncompetitive and cannot continue to exist without the tariffs, resulting in no productivity gains or the establishment of a truly competitive domestic industry?

The answer to this question lies in one word: exports.

As Pakistan moves towards near-autarky in cellphone manufacturing, the handful of local players have engaged in behaviour that is already different from the automakers in one key way: they have begun asking for policies to incentivise exports, instead of merely being satisfied with creating an oligopoly to serve the tariff-protected domestic market.

The government appears to already be in discussions with industry representatives to offer as much as an 8% tax rebate on mobile phone exports to local manufacturers if they can achieve exports equal to their imports of parts and fully assembled phones within three years. It is unclear whether or not this policy will go into effect, though the aggressive export-oriented nature of the lobbying suggests a desire to be globally competitive, which is what an industry needs to do in order to have an impact on the domestic market.

Yet industry executives caution about getting too optimistic too quickly about exports. Air Link’s management, for instance, point out that only about 20% of the value of a cellphone can even be manufactured locally, since about 80% of the value of a smartphone consists of the LCD screen, the chips, and the motherboards, which are highly specialised products that only a handful of companies produce for every single user in the world. None of them are likely to locate production facilities in Pakistan any time in the foreseeable future.

But just because a significant portion

of the value of a smartphone will continue to consist of imported components does not mean that they cannot become a meaningful generator of export earnings for the country. As the Air Link management pointed out in a briefing to analysts, that is precisely the model being followed by assemblers in Vietnam, who only assemble phones with the more complex parts continuing to be manufactured mainly in Taiwan, and yet phone assembly contributes meaningfully to Vietnam’s export totals.

And as complicated as the most valuable parts of cellphones are, laptops are even more complex, with much the same narrow supply chains involved in its highest value parts: semiconductors, LCD screens, motherboards, all precision manufactured in facilities that are so critical and so difficult to get right that the United States and China are effectively preparing for war over who gets to control those technologies.

Laptop assembly has not yet begun in Pakistan in a significant way just yet, and even cellphone assembly is quite new. It is way too early to say whether or not this is the beginnings of a large scale industrialisation of Pakistan that would include electronics manufacturing, but we do know what variables to watch out for in order to know whether or not we are headed in that direction.

If the domestic assemblers are able to begin exporting a substantial proportion of their production capacity within the next five years or so, it is likely that that the tariff protections will prove to be a truly temporary measure that helped an infant industry get on its feet and eventually become globally competitive on the strength of its own product quality.

If that does not happen, expect to live with terrible cellphone sets – or very expensive imported ones – for the next 60 years. n

Engro has become the first fertiliser manufacturer to push heavily for specialised fertilisers depending on farm needs. It is only the beginning

By Taimoor Hassan

The bosses over at Engro Fertilisers have made some changes to their sale strategy. The decision would have been taken at the company’s corporate offices in Karachi, but the implementation is supposed to take place far away in farms all over Pakistan.

You see Engro has split their sales team into two. The first team will continue to sell conventional fertilisers used in Pakistan for decades. The second team will be focused on selling specialty fertilisers, which focuses on balanced nutrition and balanced fertilisation.

For a very long time now Pakistan’s fertiliser industry has been dominated by urea and DAP. Urea constitutes around 69% of the total market share for fertilisers in Pakistan, DAP makes up about 13% of the consumption, and the remaining 18% is split between phosphates, nitrates, and other specialised products.

The split of product consumption is telling. Pakistan’s agriculture has long suffered from apathy, lack of research, and an attitude that preferes generalised solutions to specific problems. Fertilisers and their application are just one part of the problem. Contributing to approximately a quarter of the nation’s GDP and giving employment to over 90 lakh people, the agriculture sector faces a perennial problem of low yields and uncompetitive farm practices. And while the introduction of new fertiliser products from the private sector is beneficial, it is only scratching the surface of much larger issues such as the lack of farm mechanisation and modern farming techniques.

But how will these changes affect the fertiliser sector in Pakistan? Will it bolster competition or meet resistance from farming

communities that are often stuck in their ways? And most importantly, what more is there to be done?

The very core problem of modern agriculture all over the world is simple. Population growth means we need more food. Urbanisation and shrinking water resources mean there is less and less land available to farm on. The question that we are left with then is this: How do we grow more food on less land?

In more developed areas of the world, farming practices have evolved to keep up. Mechanisation through large scale machinery means time and labour can be saved. Farmers now use GPS guided tilling and harvesting machines that follow very particular paths on the farmland down to the inches to ensure the land does not lose its fertility due to overstimulation. Drone technology is used to determine the best place to plant seeds. All of these are simply farming techniques. We haven’t yet gotten into the details of seed evolution, research, and availability. Similarly, in most places, fertilisers are used methodically and in bespoke quantities. Each soil type and crop requires different treatments.

The total size of arable land in Pakistan is roughly 76 million acres with around 59 million acres under cultivation and 17 million acres unutilized. Pakistan’s two major cash crops, wheat and rice, significantly lag behind regional counterparts like Bangladesh, China, and India in terms of per-acre yield. Wheat in Pakistan averages 29.5 maunds per acre, while Bangladesh, China, and India achieve 33.4, 58.8, and 35.1 maunds per acre respectively. Similarly, rice yields in Pakistan stand at 26.7 maunds per acre, compared to 49.2 in Bangladesh, 103.2 in China, and 42.6 in India.

These inefficiencies in farm management not only hinder productivity but also contribute to broader challenges of food insecurity and sustainability. Lower yields mean less food availability, which strains the country’s ability to meet the nutritional needs of its growing population, leading to an increase in imports.

In Pakistan, the challenges faced by the agricultural sector are deeply rooted in inadequate farm management practices, with significant consequences for productivity and sustainability. At the core of these issues is the widespread unavailability of high-quality, high-yield seeds. While the rest of the world benefits from advanced seed technologies tailored to local climates and conditions, Pakistan’s seed industry struggles with limited research and development.

“This lack of innovation leads to a reliance on outdated seed varieties that are ill-suited for modern agricultural demands,” says Atif Muhammad Ali, chief commercial officer at Engro Fertilizers. “Consequently, farmers often face low germination rates and poor crop yields, hampering the sector’s potential and exacerbating food insecurity.”

Some of the high-yield crop countries such as the United States and China have cutting-edge research in agriculture that has led to the development of high-yield seeds, driven by prominent research institutions. In the US, organisations like the USDA Agricultural Research Service and the University of California’s Davis campus are renowned for their advancements in crop genetics and seed technology. Similarly, China’s research is spearheaded by institutions such as the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences and the National Key Facility for Crop Gene Resources and Genetic Improvement, which

focus on improving crop varieties to achieve higher yields.

These countries have leveraged extensive research to enhance agricultural productivity. In contrast, Pakistan’s agricultural sector lacks comparable research infrastructure and investment, leading to a significant gap in seed development and overall farm productivity. This deficiency in cutting-edge research hampers Pakistan’s ability to compete on a global scale and meet its agricultural needs effectively.

The issue of fertiliser use in Pakistan also contributes to the inefficiencies in farm management. Fertiliser application is often conducted without proper soil analysis, leading to a general approach of applying fertilisers indiscriminately.

“Farmers commonly use urea excessively, neglecting the balanced application of essential nutrients like phosphorus and potassium. This practice results in nutrient imbalances that undermine soil health and reduce crop yields. Effective farm management requires a nuanced understanding of soil content and the application of fertilisers based on specific needs, a strategy that is largely absent in current practices,” Atif explains.

Just look at the numbers on this. Urea accounts for 70-75% of the country’s fertiliser production. Meanwhile, DAP contributes around 8 – 10 % of the country’s fertiliser production since all sector players, except FFBL, are involved in the import of DAP. Other fertilisers such as CAN, NPK, NP, SSP collectively account for 15 – 20 % of the country’s annual fertiliser production. Similarly on the offtake front, urea accounts for almost 70% of the country’s total fertiliser offtake followed by DAP at 13%. The remaining fertilisers contribute the rest.

But all major crops in Pakistan require different kinds of fertilisers. Just take a look at the breakdown that one research paper has made:

In the quest to address Pakistan’s agricultural inefficiencies and bolster food security, innovative solutions need to emerge that promise transformative impacts, argues Atif. For instance the introduction of specialised fertiliser products that cater to the broader soil nutrition requirements rather than the obsession of spreading urea. This is the point we began our story with.

What specifically do we mean by this? Well, most fertilisers provide similar macro nutrients to nourish and give good yields. These nutrients include nitrogen, potassium and phosphorus. But there are other micronutrients that even in small quantities play a

minor but important role in crop health and production. Imagine then that there are specialised fertilisers that are the usual fare but laced with these micronutrients. For example regular urea has been in use in Pakistan since at least the early 1960s and began production in Pakistan in around the same era. But in 2017 Engro developed a product under the brand name Engro Zabardast Urea which comes with the additional benefits of Zinc.

According to Engro, this product has resulted in an increase in yield by 10% in both wheat and rice. Scientifically speaking, the increase in yields does not only augment farmers’ incomes by enhancing productivity on existing land, but also fortifies the nutritional content of the grain, providing essential zinc to growing children.

The value of such innovations could be enormous. Given that Pakistan imports around 2.5 million metric tons of wheat annually at a cost of approximately $600 million, a 10% boost in yield could potentially replace these imports, creating significant economic benefits. By matching the yields of more productive nations, Pakistan could add approximately $28 billion additional to its agricultural value.

The introduction of such products can also have an effect on the overall industry. Engro’s product seems to have stirred others into action as well. Indications came in late last year that after the adoption of Engro’s Zinc enhanced urea, the Fauji Fertilizer Company was also looking into Zincated Urea given the significance of additional margins, according to well-informed sources.

Remember, there is also a cost factor in these products. Last year in 2023 when it saw good adoption by farmers, Engro Zabardast Urea was sold at Rs 4,725 per 50 kg bag, which is 38.5% higher than the Engro urea price of Rs 3,411 per 50 kg bag. This is thus a significant increase in a significant input cost. And by Engro’s own estimation, the increase in overall yield is a healthy 10%. But for farmers to adopt these expensive products that they are not used to, someone must lead the way.

Many farmers remain reluctant to adopt innovative farming solutions due to a lack of awareness and education. In other words, they want to stick to bad or old farm management practices. This resistance is often rooted in a stubborn reliance on age-old methods passed down through generations. The shift towards modern agricultural practices is a gradual process, often spearheaded by progressive farmers who act as role models for their peers.

These early adopters showcase the benefits of new techniques, such as advanced fertilisers and digital farming tools, which can significantly enhance productivity and efficiency. However, the widespread adoption of

such innovations requires time and concerted effort to educate and convince the broader farming community, highlighting the need for targeted outreach and support to overcome entrenched practices.

“Our speciality teams consist of graduates in agriculture and not business graduates. We train them and their responsibility is to go to farmers, call farmer meetings and explain to farmers that other than just straight urea there are other fertilisers which you must use,” explains Atif.

Alongside fertiliser innovations, the adoption of modern agritech solutions is crucial for improving agricultural efficiency. Technologies such as precision farming, agri-fintech, digital farming platforms, smart irrigation systems, agri-drones, and soil health management offer farmers advanced tools to optimise soil use, accurately apply fertilisers, and manage water resources more effectively. These technologies promise to reduce input costs and increase farmer income, providing a much-needed boost to Pakistan’s agricultural sector.

Smart irrigation systems are another groundbreaking development. These systems use technology to precisely control water delivery, reducing waste and improving efficiency. As water scarcity becomes a critical issue worldwide, smart irrigation represents a vital step towards sustainable water management. In Pakistan, investing in such technologies could help address the acute water shortages that affect agricultural productivity. But as experts explain, such systems are expensive and therefore their vast adoption is difficult unless there is a way to finance them such as through government subsidies. Drip irrigation systems, which used to cost Rs200,000-300,000 per acre to install were subsidised by the government but they were still not affordable for average farmers. As per a report from the Government of Punjab’s agriculture department, the entire province only had 200 acres of land where a drip irrigation system was installed.

Together, the integration of high-yield seeds, innovative fertilisers, and advanced technology paves the way to fixing Pakistan’s agriculture. These innovations enhance overall farm management by implementing effective practices that improve yield and productivity. By embracing these advancements, Pakistan can significantly bolster food security and work towards long-term sustainability. Ultimately, this comprehensive approach has the potential to transform the agricultural landscape and secure a more prosperous future for its farming community. n

The

increase in revenue is driven mostly by price increases as drug manufacturers can finally raise prices based on business need and rising costs instead of regulatory fiat

In the first quarter after price deregulation, Pakistan’s pharmaceutical industry has posted its highest-ever quarterly sales, raking in a staggering Rs237 billion in the second quarter of 2024 – a 25% increase over the same quarter last year, according to data from IQVIA, a healthcare analytics firm.

This growth in revenue was driven in part by increased volumes, but mostly by increasing prices. A hefty 20% of the yearon-year increase is attributed to price hikes, while the remaining 5% is due to a rise in sales volumes. The price surge follows the government’s decision to deregulate drug prices for non-essential categories earlier this year, alongside a one-time price adjustment for 146 drugs in February 2024.

Following that robust quarter, annual revenue for the pharmaceutical sector in Pakistan hit Rs916 billion in fiscal year 2024, up 22% from the previous year. This 22% annual growth also surpasses the industry’s five-year compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 17%, suggesting that the price deregulation may have a significant impact on the pharmaceutical industry’s ability to increase its revenue in the years to come.

Historically, Pakistan’s drug pricing policies have been tightly controlled. The entire pharmaceutical industry in Pakistan is regulated by the government under a legislative framework first created by the 1966 Drug Act, which also created the Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan (DRAP).

DRAP has introduced pricing policies first in 2015 and then in 2018 that were designed to ensure that pharmaceutical companies are able to continue to make profits on their products while also not increasing the prices too much for the public. Coming as it did after a 15-year effective moratorium on drug price increases, that change was considered welcome by the industry.

But the structural problem was this: the government used to set both the retail price as well as the retailers’ margins, which effectively means that gross profit margins for the entire

industry are set by regulatory fiat. The manufacturer is able to receive a price between 20% and 25% below the retail price, which meant that the entire supply chain operated on margins contained in that 25% margin.

Pharmaceutical companies argued that they need both patent protection for the newly researched drugs that they have produced, as well as the ability to charge whatever prices they deem fit in order to be able to cover the cost of the research and development that goes into producing new and innovative therapies.

Critics of the pharmaceutical industry argued that pharmaceutical products are not like other products where a consumer has many other choices, including the ability to choose not to buy the product. A life-saving product is something that the person who needs it values very highly and would be willing to pay even extortionate levels of prices to secure access to something that will keep them alive. But it is in society’s interest that as many people as possible have access to the healthcare products they need, and hence they advocate for price controls.

The approach advocated by the pharmaceutical companies is one adopted pretty much only by the United States. Virtually every other country in the world has some form of price controls over and above any public health insurance program they may have. That means that most countries not only offer free or highly subsidized healthcare to their citizens, they also force the pharmaceutical companies to charge prices determined by government bureaucrats, and not the market.

In effect, this means that the large multinational pharmaceutical companies – whether they be American or European – make their money in the United States to help pay for the research and development activities they conduct for breakthrough therapies. The United States is subsidizing the development of advanced treatment for the whole world.

Pakistan has historically been like almost every other country in the world in that it has government-mandated price controls for pharmaceutical products. And the government

not only mandated the initial price, it mandates just how much they can go up each year, and how much each participant in the supply chain is allowed to keep as their profit margin.

The recent deregulation marks a significant shift. For the first time since the Drugs Act of 1976, pharmaceutical companies will have greater autonomy in setting prices for non-essential drugs. This decision, welcomed by the industry, is seen as a necessary correction to years of stifling regulation that left companies struggling with unsustainable profit margins amid rising production costs and a devaluing rupee.

Yet, the move has not been without controversy. Critics argue that deregulation could lead to skyrocketing prices, placing essential medicines out of reach for the average Pakistani. The Lahore High Court’s decision to stay the deregulation on February 22, 2024, was the predictable populist response to the deregulation. The stay order was then vacated on April 5, 2024.

The issue is emblematic of the broader challenges facing Pakistan’s pharmaceutical industry. The country’s reliance on imported raw materials, coupled with high inflation and currency devaluation, has squeezed profit margins to the point where companies are forced to either cut production or absorb losses. The case of Panadol—a widely used pain and fever reliever—illustrates this dilemma. Production was slashed, leading to widespread shortages, after GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare (GSKCH) struggled to secure a price increase in line with rising production costs.

The question now is whether deregulation will resolve these issues or exacerbate them. Proponents argue that by giving companies the ability to set prices, the industry will be able to maintain quality and ensure a steady supply of medicines. They point to the need for a balanced approach, where the Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan (DRAP) continues to monitor and regulate prices to prevent exploitation while allowing the market to function more freely. n

The

Punjab Government has decided it will cut the power tariff by Rs14 for consumers using up to 500 units but cutting the province’s development budget. It will do nothing for inflation except exacerbate it later, and it has other provincial governments fuming

By Abdullah Niazi

There is a sort of unspoken understanding within Pakistan’s political elite that the Chief Minister’s office in Punjab is the most sought after government position in the entire country. Punjab is the largest province by population, it gets the biggest slice of the NFC award (Sindh comes in second at around half the amount Punjab gets), and has the most number of industrial cities in the country.

Any man or woman that finds his or herself occupying the CM house in Lahore is presented with an incredible opportunity to run good looking projects in education, health, and other important sectors on as large a scale as possible without the headache of fixing the economy or managing Pakistan’s foreign policy.

On top of that, Takht-e-Punjab is considered a stepping stone to the Prime Minister’s office, which is largely an unearned reputation. Only four men have graduated from Chief Minister of Punjab to the Prime Minister’s office. The first two, Feroz Khan Noon and Malik Meraj Khalid, did so on technical grounds. Mr Noon was briefly prime minister for just under 10 months in 1958. Before his brief premiership, Mr Noon was unilaterally appointed chief minister of Punjab from 1953-55 at a time when provincial elections and legislatures were not a developed concept. Similarly, Malik Meraj Khalid was Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s pick for Chief Minister before he became Prime Minister in the 1990s in a caretaker capacity.

There are really only three men that have gone from CM to PM in Pakistan through the electoral process. One of them, Zafrullah Khan Jamali, was the executive of the Balochistan government twice before he became prime minister in 2002. The other two are brothers.

Mian Nawaz Sharif and Mian Shehbaz Sharif both went from leading the Punjab government to the federal government.

But even as the younger Sharif stumbles through his second stint as prime minister, his older brother is perhaps the first to voluntarily take a bit of a backslide on the political ladder. Ever since the February elections where the PML-N barely managed to form a coalition government even after the elimination of their opponents the PTI, Mian Nawaz has seemed more interested in the affairs of the Punjab Government than with his party’s government in Islamabad.

Perhaps that is why it was Mian Nawaz, and not his daughter the Chief Minister, who made the announcement that the Punjab Government was cutting the power tariff for domestic consumers using less than 500 units by Rs14. The subsidy is expected to cost at least Rs700 billion, and the money for it will come at the expense of development projects, even though the former prime minister failed to specify which part of the development budget this money would come out of.

The decision seems desperate. The amount of money set out for the subsidy will make it last only about two or three months. The subsidy is also coming right after peak electricity consumption season, which means bills are going to go down anyway and the number of consumers using less than 500 units will increase. On top of this, the decision has caused problems for his younger brother’s government at the centre, where coalition allies are unhappy with the scheme and suspicious that part of the funding will come from Islamabad.

The only question is: what in the world does Mian Nawaz achieve from this plan?

The short answer is nothing. The subsidy is a combination of internal PML-N politics and

How sustainable is this temporary measure by the Punjab government really? We don’t want to drain out public money for any temporary good after creating a mess

Murad Ali Shah, chief minister of Sindh

old fashioned political beliefs that Mian Nawaz holds dear which dictate short-term, expensive solutions as a way of cheering up the electorate. Historically, no such scheme has worked out and has only ever led to deeper financial problems. But how exactly will it play out?

It is not exactly great for Maryam Nawaz’s political career that her father seems to be running her government. It is even worse that he does not even bother to do this from behind the scenes. Since his daughter took charge, Mian Nawaz has regularly chaired meetings of the Punjab Government. There is some legal basis for him to do so, considering he is the President of the PML-N and as such has legislative authority over his MPAs but it has not exactly been a good look.

But it does seem Mian Nawaz’s involvement in the Punjab Government is to ensure his daughter’s government becomes more prominent in the eyes of Punjab’s voters over his brother’s government at the centre. The relief plan announced by the Punjab Government on the 17th of August said customers using up to 500 units will get a subsidy of Rs14 per unit in August and September.