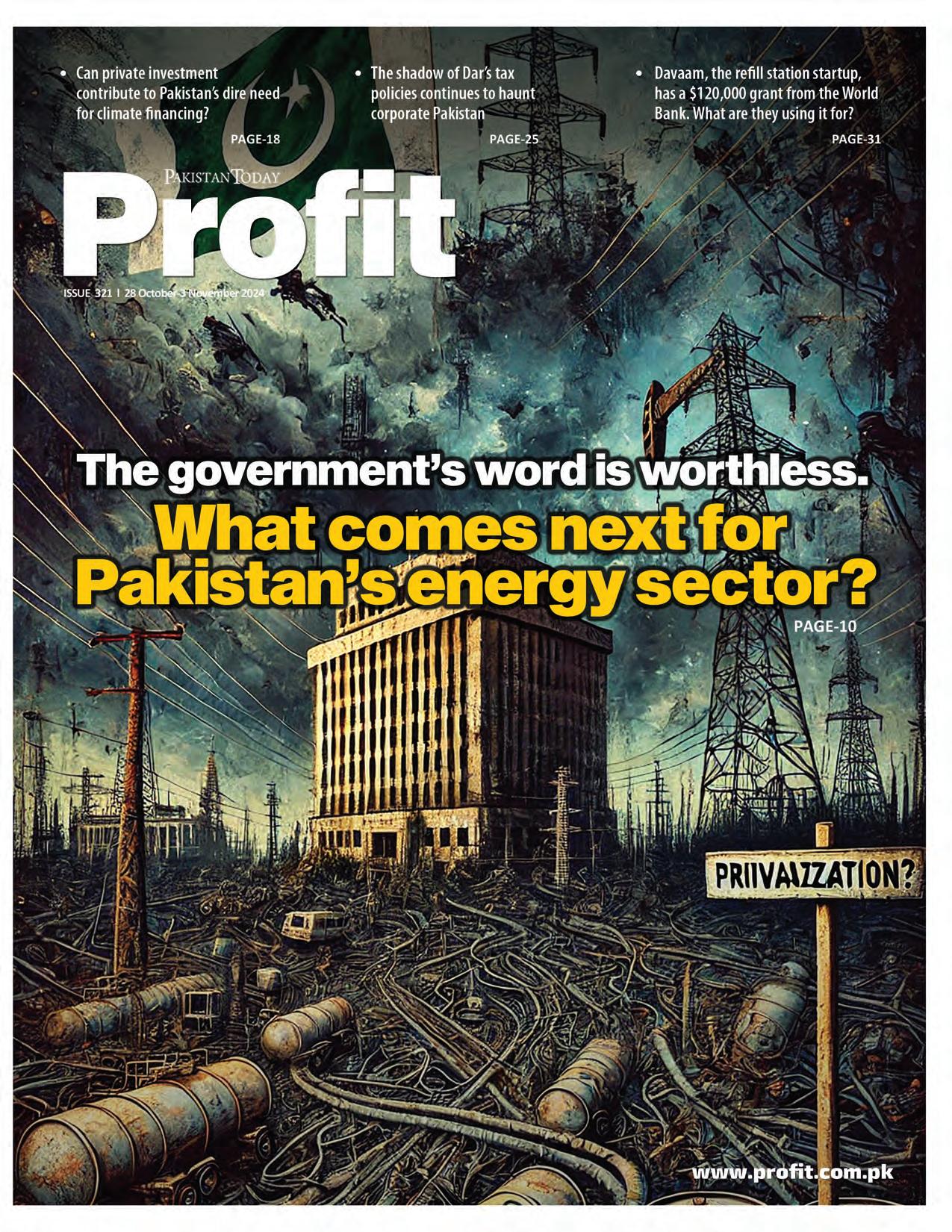

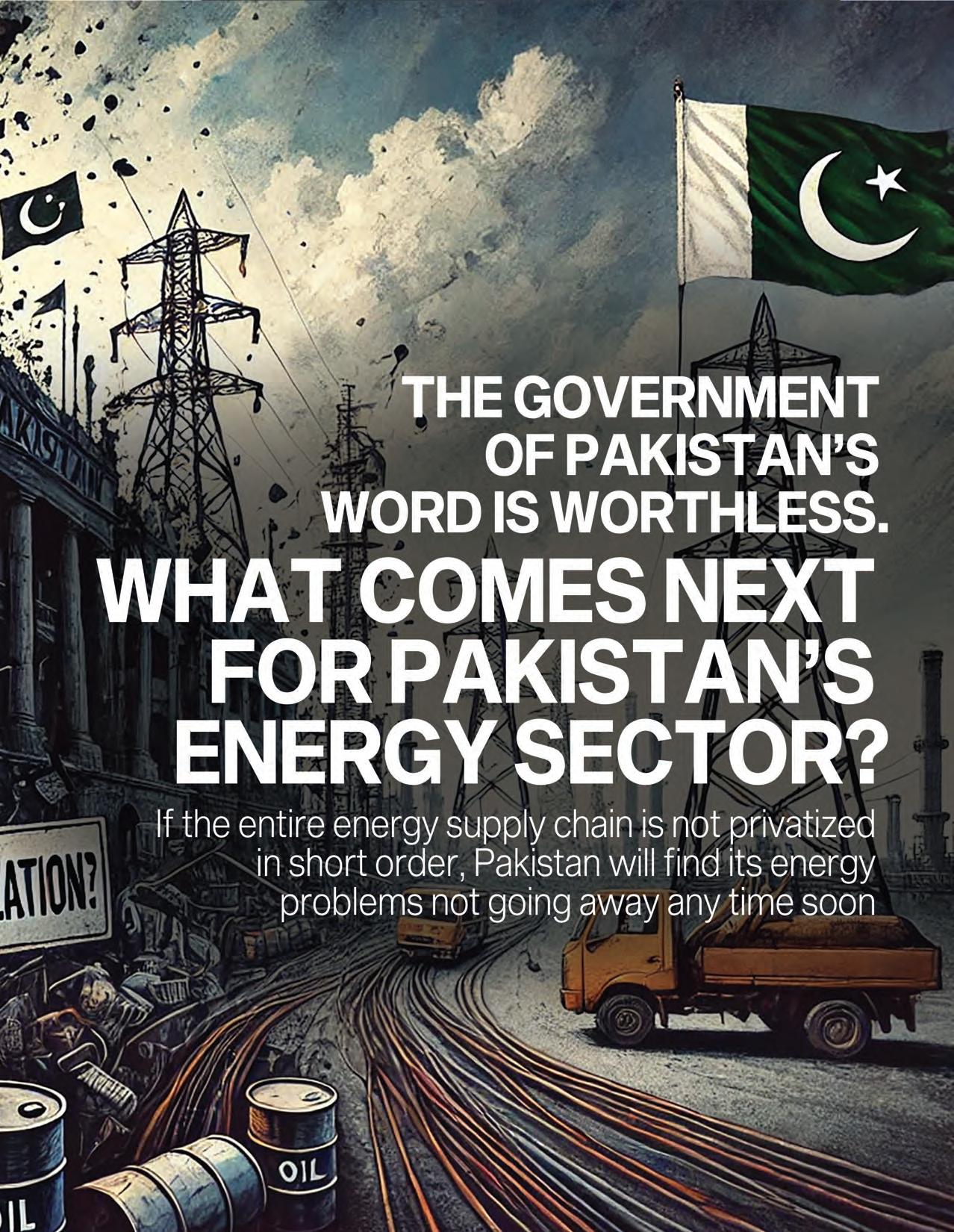

10 The government of Pakistan’s word is worthless. What comes next for Pakistan’s energy sector?

18 Can private investment contribute to Pakistan’s dire need for climate financing?

20 With new regulation and licences, what are the implications for branchless banking?

25 The shadow of Dar’s tax policies continues to haunt corporate Pakistan

28 In CCP hearing, Zong claims PTCL’s acquisition of Telenor will create an uncompetitive environment. Why do they say that?

31 Davaam, the refill station startup, has a $120,000 grant from the World Bank. What are they using it for?

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz Khan - Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Editorial Consultant: Ahtasam Ahmad - Business Reporters: Taimoor Hassan | Shahab Omer

Zain Naeem | Saneela Jawad | Nisma Riaz | Mariam Umar | Shahnawaz Ali | Ghulam Abbass

Ahmad Ahmadani | Aziz Buneri - Sub-Editor: Saddam Hussain - Video Producer: Talha Farooqi Director Marketing : Mudassir Alam - Regional Heads of Marketing: Agha Anwer (Khi) Kamal Rizvi (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) - Manager Subscriptions: Irfan Farooq Pakistan’s #1 business magazine - your go-to source for business, economic and financial news. Contact us: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

By Farooq Tirmizi

In a large, ornate conference room in one of the higher floors of the building of the New York Stock Exchange, there is a rather expensive-looking vase that once belonged to Tsar Nicholas II of Russia. The vase was sent to the exchange as part of the collateral against a bond issued by the imperial Russian government to finance their expenses during World War I. When the Bolsheviks took control during the Russian Revolution, they reneged on all of Russia’s debts and made a separate peace with Germany.

In the mid-1990s, after the communists heirs of the Russian Revolution had been pushed out for a – briefly – democratic Russia, the Russian government tried to make a comeback on the international bond market, and as part of that effort, Russian leaders toured financial institutions in the United States, including the New York Stock Exchange. During their tour of the NYSE, they saw the vases and asked if they could be returned to Russia. The NYSE officials giving the tour said: “Absolutely. Right after you pay back the money the Tsar borrowed.”

The market has a long, long memory. It does not forget. And it especially does not forget a sovereign that reneges on its debts.

There are many ways to spin the socalled “renegotiation” of the government’s contracts with independent power producers, but make no mistake about what it is, and how the market will view it. It is a sovereign default by the government of Pakistan. And the market will not forget it – or forgive it –any time soon.

The mess that is Pakistan’s power sector has few, if any, heroes and there is a lot of blame to go around. But while it is possible to say that nearly everyone is to blame, only the government of Pakistan is responsible for what comes next.

The good news is that this sovereign default could be the start of a permanent fix to the problem. The bad news is that this government has made it clear that they do not have the capacity to seize this opportunity.

You have doubtless read many pieces talking about what has gone wrong, and we will certainly examine how this mess was created, how each party in the entire energy supply chain is at least partly to blame for this mess, and the dangerous consequences of what the government has done with the IPPs.

But we will also provide you something else that you may not find in other news sources: how the government can get out of this mess. We are not optimistic that the government will take our analysis seriously, but it is worth trying anyway.

Let us start this conversation about blame by first explicitly saying what happened. The government of Pakistan, de facto run by the Pakistan Army, forced the owners of independent power plants (IPPs) to “agree” to the annulment of their contracts with the government-owned company that has a legal monopoly on buying electricity from any power company in Pakistan.

We have no evidence to suggest that guns were used, but they did not need to be physically present for us to characterize these agreements as having been secured virtually at gunpoint. The government pointed a gun at the heads of the majority shareholders of the IPPs and said to them: “You have contracts that say we owe you money. Announce to the world that you are giving up your claims to the money we owe you.”

Oh sure, there were the final settlement amounts, and no doubt the accountants and lawyers will haggle over definitions and numbers, but none of that matters. What matters is that the government used brute force to get out of its contractual obligations.

Why does this matter? The government of Pakistan has always had the power to use brute force to get out of contracts. But while Pakistan has never really had rule of law, we could reasonably claim to be on the path to one day achieving the rule of law because the government of Pakistan did things like at least trying not to break contracts it had entered into, even during moments of extreme financial duress, when it may have delayed payments it owed, but it never renounced its obligations outright.

Well, now they have. Yes, they have reasons, and yes those reasons sound reasonable because they are. The reality of this situation is enormously complicated and requires an understanding of nuance generally absent from most discussions of politics or economic policy in Pakistan. The fact is that the contracts the government entered into with the IPPs should probably never have been signed in the first place. There were too many IPPs that got sovereign guarantees, some (but not all) of them were granted guaranteed rates of return that were too high. And those too many and too generous contracts were costing the electricity system too much money and causing consumer electricity bills to rise too high.

Something had to be done, so the government decided to undo those contracts that were the original sin. It sounds reasonable.

But that is if you assume that the contracts with the IPPs are where the problem started. It is, quite obviously, not.

Think about why IPPs were even conceived of in the first place. The Hub Power Company (Hubco) was the first IPP and was set up in 1994. What was happening back then? The country’s power grid, then managed by the Water and Power Development Authority (WAPDA) had completely lost the ability to keep pace with the country’s needs.

WAPDA is a government department, and hence dependent on government funding to be able to invest in power generation. But the government invested far too little in power generation in the Zia era, which caused the electricity shortage in the country to be exacerbated.

The solution, proposed and financed by the World Bank, was to allow private investors to finance the construction of power plants. But since the government was the only buyer of electricity, that introduced a level of risk that no reasonable investor would ever want to take: if you have only one customer, then your business only lasts as long as that customer wants to buy from you. The day they change their mind is the day you go bankrupt.

So the World Bank proposed a solution that was implemented for the first time anywhere in the world with Hubco: not only would the government agree to buy the full electricity that the power plant would produce, but that agreement to buy the electricity would be tied to its sovereign credit rating that it uses to borrow from global lenders, including the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The government would either have to buy the electricity that the company made available, or else it would have to pay a “capacity charge”, a phrase that has been the subject of intense debate in Pakistan recently.

The contracts also included guaranteed returns, which served two purposes: the first was to ensure that the returns would be high enough that investors would want to put their cash into setting up power plants in Pakistan. (Remember: before Hubco in 1994, nobody had ever done this in any developing country in the world.) And the second was to set up a mechanism that would try to mimic how a market-based pricing mechanism might work, in the absence of an actual market to determine prices at which the company would sell its electricity.

IPPs did this long, convoluted workaround to a basic problem: the government wanted to maintain control of the electricity grid through WAPDA, even though the politics of the budget meant that allocating mon -

ey towards electricity generation projects was rarely a priority. Extending electricity connections as part of village electrification programs, the government wanted to do. Setting up the power plants to supply that electricity, they did not.

But instead of giving up the initial source of the folly – which was to politicise who got an electricity connection by maintaining tight political control over WAPDA – the government decided to find a workaround by offering these contracts to IPPs, so that they could keep doling out political favours anyway.

In this, as in just about all things, the government of Pakistan’s attitude is that

they need to maintain control, when it fact their actual responsibility is to maintain order. The two are not the same thing, but the government seems unable to tell the difference.

To be clear, the government is far from the only one to blame for the problem. The IPPs were initially given generous, dollar-linked contracts that were to last for 25 years. Ideally, companies like Hubco should have been planning for a 25-year run with the initial

plant and then planning for fresh contracts, perhaps even on slightly less generous terms, for subsequent contracts. They made no such preparations.

Instead, the industry as a whole piled into contracts that were clearly too generous, though the government designed them that way precisely because it wanted to attract as much capital as possible to electricity generation. But the companies should have known better. They should not have leaped into contracts with the government that they knew were too good to be true, and even after the government had spent decades failing to pay on time.

And of course, we the citizens are

also at fault because we either engaged in otherwise tolerated the stealing of electricity which meant that the cost of electricity always had to include the cost of theft, making honest citizens feel duped for paying high prices for a poor quality of service, making at least some people feel justified in stealing, resulting in yet more increases to the costs of electricity in a vicious circle that kept making the problem worse.

Reading this might lead some policymakers – in uniform or outside of it – to believe that they did the right thing. That the companies themselves were to blame, and so forcing them to give up their contracts was the right thing to do.

Instead of giving you an opinion on that, we will lay out what is likely to happen as a result of that decision.

The biggest consequence of what has been done is now the following: the government of Pakistan’s word is utterly worthless. No intelligent person in Pakistan should ever do business with the government ever again because to do so is to do business with a known liar and a fraud. Indeed, the only people who will continue to engage in commercial transactions with the government will be the talentless hacks who only know how to make money by currying favour with the government. Sycophants and amoral creeps with no qualms about bribery will continue to court the government, but the reputable business houses in Pakistan – of which there is a small, but increasing number – will stay away.

Unfortunately for us, given the current state of surplus capacity in the nation’s

electricity grid, it will be several years before the government feels the consequences of this decision. But when the current surplus capacity runs out – probably in about a decade – the government will finally feel the effects of what it has done this year, and it will go something like this. These sycophants are typically people who are not very talented at doing technically difficult things, which means they will either fail to get their projects off the ground, or even when they do, they will do so in a much less efficient manner than the current crop of investors. Functionally, it will be nearly impossible for the government to convince anyone to come and set up private sector power plants with government buyers in Pakistan. Once you lose the trust of a market, it takes decades to win it back, and sometimes not even then. The government has some time before it runs out of the current surplus capacity of electricity, but it does not

have infinite time. To understand just how thoroughly the government’s actions decimate trust, let us take a look at another example. In the 1990s, the government promised Pakistanis that they could keep their money in US dollars at Pakistani bank accounts and that those accounts would be full convertible and unrestricted. In 1998, after a run on the banks’, the government took the seemingly reasonable-sounding measure of first suspending withdrawals, and then only allowing very small quantities at a highly inflated exchange rate relative to the US dollar. People lost their trust in the system so badly that even now, 26 years later, foreign currency accounts at Pakistani banks have not even reach the nominal levels they reached in the 1990s/.

A generation lost trust in the government’s promise about US dollar deposits, and their children are still unwilling to trust the government with dollar deposits. If the country’s electricity grid’s surplus capacity will only last about a decade, but it takes more than 25 years to recover the trust that has now been lost, what do we think is going to happen during the first 15 years after surplus is gone? The same thing that is happening now: no material improvement to load shedding, and a mad dash to try to dole out even more outrageously generous incentives to try to persuade investors to trust the government again. Beyond just the logistical challenges, though, do we sincerely believe that having a government that our own citizens and the world believe to be liars can ever help form the basis of a shared prosperity? Do we think shattered trust can ever give birth to the kind of society we want to live in?

What is the one way to solve the problem of nobody believing that the government is a reliable counterparty in the

energy sector? Stop having the government be anybody’s counterparty in the energy sector.

If the government retains control over the electricity supply chain, but also reneges on its contracts, the electricity sector of Pakistan will effectively cease to function. But if the government reneges on contracts, but then stops forcing anyone to sell 100% of their electricity to the government, then the reneging of the contracts becomes something different. It would be viewed as the government cancelling bad contracts before instituting structural reforms and handing off a cleaned up electricity grid to the private sector to manage through privatization.

Privatization now, after having eliminated the most expensive contracts, would change the dynamic completely. This would not be the government proving itself the untrustworthy counterparty, it would be the government fixing the original sin, which was seeking absolute control over the electricity grid.

By letting the market take over after giving it a clean slate, the government would demonstrate that it has the ability to solve big problems for the country. It would have massively increased the electricity generation capacity of the country, put the electricity transmission and distribution companies on a much sounder financial footing, and then finally admitted that it did not need to micromanage this vital sector of the economy.

Will this happen? Probably not.

The core problem with the government of Pakistan is that they believe that control is the only way to maintain order. They believe the

voters are stupid, and will only give them credit for explicit things they do for them. So, for example, every politicians lives for the day they get to announce a reduction in the prices of some essential item that the government controls.

They cannot fathom the idea that voters can be trusted with the truth, and that they will give credit to a government that creates a broadly felt prosperity, even if the government is not explicitly doing things that make people feel happy.

The current military-led government, with its pre-occupation with trying to control the contours of the country’s political spectrum – is particularly unsuited to implementing a policy that would involve them ceding control.

They know they have to privatise something because the IMF is forcing them to do so, so they decided to privatise the kind of things that do not give them control over every day prices. Hence the prioritization of Pakistan International Airlines for privatization.

It will do very little to revitalize economic growth in Pakistan to privatise PIA, but it will also mean they will not giving up the ability to provide “relief” to ordinary voters. Privatizing the electricity distribution companies is something the government is petrified of doing, even though it would effectively eliminate load shedding in urban Punjab within a couple of years, and kick off a boom in small-scale industrial activity that would create the kind of economic growth that could alter the very mood of the country.

Could the government surprise us yet? Theoretically, yes. But practically, it looks very much like the government’s plan to solve one problem is to create another. n COVER STORY

NRSP and Sarmayacar have partnered with GCF, a $50 million fund, in a move to reinvigorate Pakistan’s climate tech landscape

By Ahtasam Ahmad

In 2023, Pakistan was in the spotlight. At the COP 28 conference in Dubai, the entire world was looking towards Pakistan both as an example and an opportunity. The year before in 2022 historic monsoon rains had devastated Pakistan, causing over $30 billion in losses and damages.

The entire episode was a stark reminder of Pakistan’s vulnerability to climate change. At the COP28 conference, mostly because of the situation in Pakistan, one of the topics that was front and centre was loss and damage reparations from first world countries to vulnerable third world economies. Despite all the talk, international climate funding is a complicated business, particularly coming from international organisations.

In the midst of this traditional reliance

on international aid, a new initiative is emerging that could transform how Pakistan tackles its climate challenges. The National Rural Support Programme (NRSP) alongside Sarmayacar has just secured Green Climate Fund (GCF) support for a $50 million Climaventures Programme, marking a decisive shift from Pakistan’s toward nurturing home-grown solutions through its burgeoning startup ecosystem.

The numbers tell a sobering story. According to the Post-Disaster Needs Assessment report, Pakistan needs at least $16.3 billion just for post-flood rehabilitation and reconstruction. The 2022 floods alone inflicted $14.9 billion in damages and $15.2 billion in losses. But these figures represent only a fraction of the climate challenge facing the world’s eighth most vulnerable

nation to climate change.

Standing at the crossroads of melting glaciers and persistent droughts, Pakistan faces a monumental task. The World Bank estimates that the country needs approximately $348 billion by 2030 – a staggering 10% of its cumulative GDP – to implement comprehensive climate solutions. Of this, $152 billion is earmarked for adaptation and resilience, while $196 billion is needed for decarbonization efforts.

The challenge is further complicated by Pakistan’s international commitments. As a signatory to the Paris Agreement, the nation has pledged to reduce its projected carbon emissions by 50% between 2015 and 2030. While 15% of this reduction will come from domestic resources, the remaining 35% depends on international financial support, demanding sweeping changes across energy, transportation, waste, and agriculture sectors.

Enter the Climaventures Programme, a novel approach to addressing Pakistan’s climate funding crisis. Rather than depending solely on public sector funding – already strained by high indebtedness – the initiative aims to catalyze a private capital for innovative climate solutions through a two-pronged strategy.

At its foundation lies a $10 million Venture Accelerator, backed by a reimbursable grant and a technical assistance facility from the GCF. This component will serve as an incubator for climate-focused businesses at their earliest stages, providing both financial support and technical expertise to help entrepreneurs transform their ideas into viable products ready for market.

The second component, the $40 million Climaventures Fund, represents an even more ambitious step. Managed by Sarmayacar, Pakistan’s first formal venture capital institution, the fund will invest in climate ventures ready to scale.

What makes this fund particularly innovative is the GCF’s $15 million first-loss equity commitment as an anchor investor – a structure that effectively creates a safety net for other investors, making the fund more attractive to Development Finance Institutions and International Financial Institutions.

Investors Amount

GCF 15

Development 10

“We are targeting both DFIs and commercial investors in addition to the commitment from GCF. The latter’s commitment also comes with first-loss cover for commercial investors so their risk-return profile will look even better. We will be targeting commercial returns with impact for all investors, but this first-loss cover offers some downside protection to incentivise private sector participation in the fund,” remarked Rabeel Warraich, Founder and CEO at Sarmayacar.

The landscape of climate technology in Pakistan is as vast as it is underexplored. From carbon capture solutions to sustainable foods, from low-carbon mobility to clean energy, the po-

As per estimated by the GP based on market conditions and the performance of invested companies, the fund will target a gross return of 3x

Class A Interests will be allocated to investors Financial with mission orientation and no requirements for Institutions (DFIs) downside protection, such as development finance institutions and institutional foundations

Non-DFIs/Private 14.6

Class B Interests will be allocated to investors with Investors a commercial mission orientation, such as private individuals, corporations and pooled funds.

Key Persons/GP 0.4

Class D Junior Interests allocated to the Carry Vehicle

tential for innovation spans every sector of the economy. Yet, climate tech has only managed to attract merely 2-3% of total startup venture funding between 2018-2023 in Pakistan, with most investments concentrated in e-mobility and agritech ventures. Even more telling is the average deal size – less than half that of the broader startup ecosystem.

This tepid investment climate stems from multiple challenges. The domestic private sector’s engagement in climate action remains notably low, with Pakistan’s private sector accounting for just 5% of total climate finance tracked in 2021 – significantly behind peers like Nigeria at 10% and Kenya at 14%. Current donor-funded climate programs often prioritize short-term metrics over sustainable impact, while policy implementation lacks clear operational frameworks.

For entrepreneurs, the barriers are even more immediate. Beyond the usual startup challenges, climate tech ventures require substantial capital expenditure and face heightened risk perception in nascent green sectors. Many struggle to access even basic support services – market feasibility studies alone can cost between thousands of dollars, putting them out of reach for most early-stage ventures.

Despite these challenges, NRSP, in its proposal to GCF, claims to have identified over 100 ideation-stage climate ventures operating within Pakistan’s climate sector, with more emerging as awareness grows.

In parallel, Sarmayacar steps in as an investor, having previously invested in climate tech startups, including Orko – a platform tailored for Electric Vehicle (EV) diagnostics and after-sales service management and Aabshar – a water conservation venture, through their initial $25 million fund in 2018. For the new Climaventures Fund, they’ve already identified ventures ready for investments totaling approximately $22 million as per documents

submitted with GCF.

“There is an existing pipeline that could use up to half of the fund we have targeted. We made a couple of climate-related investments from the first fund as well. Once there is a dedicated fund, we expect a number of new startups to emerge in the space so over the investment period of the fund, we hope to be able to find 15-20 companies to invest in,” Warraich adds.

The financial projections for the fund also look promising, even in the face of challenging macroeconomic conditions. As per the submissions to GCF, the projected gross returns for the fund are between 2.9x and 4.1x, translating to net returns of 2.5x to 3.5x and a seven-year IRR of 14% to 20%. But perhaps more importantly, the fund’s biggest impact lies in its ability to demonstrate that early-stage climate ventures can be a viable asset class while delivering meaningful environmental impact.

The Climaventures Programme targets both immediate climate impact –aiming to mitigate 3.5 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent –and long-term market development, potentially benefiting nearly 6 million people in Pakistan’s climate-vulnerable population. As Pakistan continues to grapple with increasing climate vulnerability and limited public resources, similar initiatives are likely to pop up in an attempt to experiment in leveraging private sector innovation for climate action.

Yet, unlike other funds the stakes here are higher. Alongside Acumen’s $80 million Climate Action Fund (also backed by GCF), this $50 million bet on home-grown innovation might just be the catalyst Pakistan needs to build a more resilient future.

Success could transform Pakistan’s approach to climate challenges, shifting from dependency on international aid to fostering sustainable, locally-driven solutions. n

With new regulation and licences, what are the implications for branchless banking?

JazzCash and Easypaisa dominate branchless banking, but then why are they keen on gaining licences to be ‘digital banks’?

By Mariam Umar

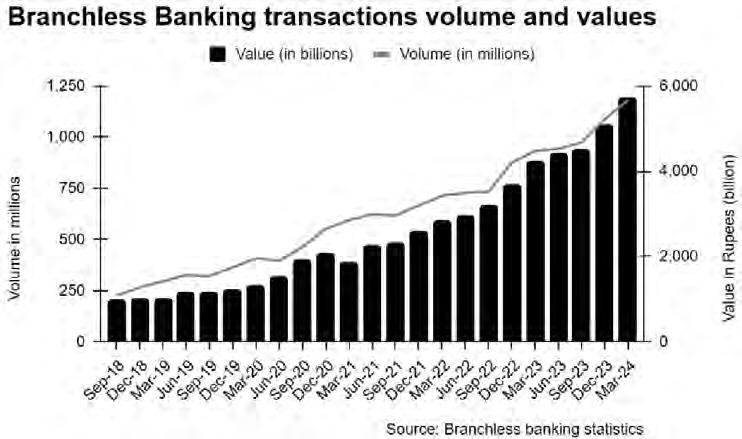

Perhaps nothing speaks to the success of JazzCash and Easypaisa more than the fact that they control 70% of the total value of branchless banking transactions that take place in the country, and just over 80% of the total volume of these transactions.

It is important to define a few terms here before we get into why this matters. Branchless banking is a very specific category within the banking sector, defined by what licence has been granted to a financial institution by the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP). Branchless banking is not a term used to define online banking as a whole, but for institutions like JazzCash and Easypaisa which provide certain financial services without having branches. And these two are not the only players in the market, even though they have become synonymous with the concept. In fact, traditional banks like HBL and UBL have also introduced their own branchless banking services such as Konnect and Omni.

That is what really matters. Even though major banks made a pretty big splash trying to get in on the branchless banking segment, the telco backed JazzCash and Easypaisa have dominated the segment. But the era of branchless banking might be changing. The SBP has introduced new regulatory measures, particularly its new digital banking licence, that could signal a turning point for the industry.

These digital banking licences, set to launch operations by 2025, may alter the landscape as existing branchless banking providers evaluate whether they should transition fully to digital banking models or remain within the branchless banking framework. This article explores the history of branchless banking in Pakistan, its rise through the efforts of telecom giants, challenges faced by traditional banking institutions, and the regulatory changes that may redefine this sector.

The seeds were sown in March 2008, when the SBP introduced regulations to enable banking without the physical presence of branches. This move aimed to increase financial inclusion in a country where traditional banking systems had long been out of reach for vast rural populations and underserved communities. The SBP’s regulations allowed financial services to be delivered through mobile networks and authorised agents, bypassing the need for physical branches.

At the time, this was not particularly groundbreaking. Pakistan still did not have fast mobile internet, and the banking sector was sluggishly digitising their existence. But over

time, all of these factors combined to create the perfect environment for a digital banking experience.

By 2016, the branchless banking framework expanded, and in December 2019, SBP introduced updates to address operational challenges. This evolved framework helped providers innovate on services like account creation and money transfers. Through these successive reforms, branchless banking became a cost-effective alternative to conventional branch-based banking and empowered financial institutions to access previously untapped rural and remote markets. “When branchless banking first emerged, it revolutionised access to financial services by eliminating the need for physical branches,” says Monis Rehman, a fintech veteran in Pakistan.

The core difference between a branchless banking licence and a conventional banking licence lies in how services are delivered. While conventional banking requires physical branches to conduct operations, branchless banking relies on mobile networks, agents, and digital platforms to facilitate account creation, payments, and money transfers. Unlike traditional banks that must invest in costly infrastructure, branchless banking can tap into existing telecom networks, drastically reducing operational costs.

Prior to the branchless banking framework, individuals needed to physically visit a bank branch, provide documents, and go through face-to-face verification to open a bank account. The branchless banking framework changed this, allowing customers to open accounts outside of traditional branches, and even via mobile phones.

“The branchless banking framework was a pioneering move by the State Bank of Pakistan that facilitated a wave of online account creation. This led to the majority of financial accounts being opened through JazzCash and Easypaisa as these providers launched early. They initially operated with microfinance bank licences and later transitioned to branchless banking licences. Consequently, in SBP’s reports, JazzCash and Easypaisa are categorised under the branchless banking segment due to the licence type they currently hold.”

The introduction of branchless banking allowed telecom companies to enter the financial services sector, leading to the creation of new financial ecosystems. Telcos like Telenor and Jazz, which already had extensive networks of agents, retail outlets, and large user bases, capitalised on the opportunity to introduce mobile financial services.

Easypaisa, launched by Telenor’s Tameer Microfinance Bank in October 2009, was the

first major player in the sector. By allowing users to perform transactions and bill payments over-the-counter, even without having a Tameer bank account or Telenor phone, Easypaisa opened financial services to millions. JazzCash followed in November 2012, with Mobilink (now Jazz) leveraging its extensive agent network to provide similar services. As of 2023, JazzCash operated over 238,000 agents, while Easypaisa managed around 213,000.

Telcos in Pakistan were interested in branchless banking for several reasons. Firstly, the telcos were looking to diversify their income as their voice business was not making them money. Speaking at the first merger and acquisition conference organised by TerraBiz on December 7, 2016, Nadeem Hussain, the founder of Tameer Bank, informed that telcos Average Revenue Per User (ARPU) had come down from $15 to $2 while Telenor Pakistan had invested $1-1.5 billion in infrastructure, merchant networks and licences.

Besides, telcos already had a widespread network of agents and retail outlets, which they could use to offer banking services without significant additional investment, they also had a large customer base that they could tap into. By entering the branchless banking sector, telcos could capitalise on their strengths and expand their service offerings, ultimately benefiting both their business and the broader community by improving access to financial services.

Both JazzCash and Easypaisa used these established agent networks to serve Pakistan’s unbanked population effectively. Their cumulative reach has enabled them to process approximately 70% of branchless banking transactions in Pakistan. In 2023 alone, Easypaisa and JazzCash processed transactions worth Rs 6.9 trillion and Rs 5.8 trillion, respectively.

This success, however, was largely unattainable for traditional banks, which struggled to replicate the telcos’ agent-based model. Conventional banks had been quick to jump on the opportunity to expand their network without investing in new brick and mortar branches.

Motivated by the success of telecom-based branchless banking, several traditional banks attempted to launch similar services. UBL Omni, launched in 2010, sought to replicate the telecom model by providing over-the-counter bill payment services. Likewise, in 2012, Askari Bank partnered with Zong to introduce Timepey, a branchless banking initiative. Despite having over 3,000 agents at its peak, Timepey struggled to achieve profitability and ceased operations in 2016. HBL’s Konnect launched in 2018 but has yet to

match the scale and market share achieved by JazzCash and Easypaisa.

Maintaining a network for branchless banking is a pretty expensive proposition, and the telcos had the advantage of an existing network. The dominance of JazzCash and Easypaisa stems from their reliance on telecom infrastructures, particularly the vast networks of agents spread across Pakistan’s rural areas, where bank branches are scarce. In contrast, traditional banks faced high costs and logistical challenges in setting up similar networks. As Rahman noted, “Just because someone has a branchless banking licence does not mean that they have the ability to execute.”

Why were telcos more successful?

According to the recent annual payment systems report, the branchless banking landscape consists of 16 key players. We have already mentioned three earlier. Apart from these, others include microfinance banks like Finca Microfinance Bank, U Microfinance Bank, NRSP Microfinance Bank, and HBL Microfinance Bank. Additionally, commercial banks like JS Bank, Dubai Islamic Bank, BOP, Askari Bank, MCB Bank, Allied Bank, United Bank, Meezan Bank, Habib Bank Limited, and Bank Alfalah also possess branchless banking licence.

Habib Bank Limited offers Konnect, a digital mobile wallet that was launched in 2018.

Looking at the success of easypaisa, the commercial banks also attempted their foray into branchless banking. While telco-led branchless banking thrived, the commercial banks’ attempts were less successful.

For example, in 2012, Askari Bank announced the launching of a pilot project called Timepey, a branchless banking solution in collaboration with Zong. At that time Timpey had 3000 agents. However, the mobile-based banking service ceased to exist in 2016. How-

ever, Zong attempted to enter the payments business again later in 2022.

Similarly, in 2014, Warid Telecom and Bank Alfalah Limited announced the launch of their marketing campaign for Branchless Banking Services under the brand name Mobile Paisa in Pakistan with Monet (Pvt) Limited as the technology provider. (Later in 2017, Jazz acquired Warid).

Even though there are 16 players in the branchless banking, JazzCash and Easypaisa account for almost 80% of transactions undertaken by branchless banking wallets. “Just because someone has a branchless banking licence does not mean that they have the ability to execute,” remarked Rahman.

The reason why JazzCash and Easypaisa have been able to dominate the branchless banking market is that they had access to the extensive agent networks of the telecommunication companies.

In Pakistan, telecom operators sell their products through a few key channels: digital platforms and a vast retail distribution network of franchises and agents.

The telcos’ mobile applications, such as Ufone’s “My Ufone” app, allow customers to transfer money from their bank accounts or digital wallets to recharge their airtime and make purchases.

Moreover, Telenor Pakistan and Jazz, like other telcos, leveraged their extensive franchise and retail distribution networks to reach consumers across the country. These franchise partners have contractual relationships with the telcos, and they oversee a network of retailers who sell various products, including airtime.

This retail network plays a crucial role due to the relatively low smartphone penetration in Pakistan, which stands at around 50% according to industry estimates. However, as

smartphone adoption increases in the future, the need for this distribution network may diminish.

The access to this extensive telco agent network is what enabled JazzCash and Easypaisa to effectively reach and engage the underserved segments of the population, contributing to their dominant position in the branchless banking space as the majority of the country is poor.

While branchless banking experienced consistent growth in transactions over the years, maintaining a large network of agents has proven costly, leading to a decline in the number of active agents in recent years. Between 2023 and 2024, active agents declined by 53,000, highlighting a potential saturation point as operational expenses have risen.

Easypaisa and JazzCash have gradually shifted focus toward promoting digital wallets rather than solely relying on cash-based agent transactions, which are both resource-intensive and prone to logistical complications. Although the number of branchless banking transactions increased by around 7.5% each quarter, the average transaction size has remained relatively static over 23 quarters, showing only a slight 0.5% increase. This suggests that while transaction volumes are growing, they are mostly small in size, limiting the profit potential for providers.

The regulatory landscape in Pakistan has evolved significantly since the introduction of branchless banking. The SBP initially required entities

interested in mobile payments to own a bank, a model that prompted telcos to purchase microfinance banks to gain branchless banking licences. However, with the introduction of Electronic Money Institution (EMI) licences in 2019 and digital banking licences in 2022, the central bank has opened alternative paths for non-bank entities to enter the digital payments ecosystem.

The EMI licence permits entities to accept deposits and facilitate transactions but does not allow them to lend funds. Players like Nayapay and Finja have entered the market under these licences, while telecom company Zong attempted to launch its own payments solution, PayMax, in 2022. However, in October 2023, Zong applied to surrender the PayMax licence, highlighting the limited revenue potential of EMI licences. As Amer Pasha, former Visa country head, commented, “The EMI licence represents a more restricted set

of financial services compared to a full-fledged banking licence.”

The digital banking licence, on the other hand, has offered a more robust alternative by allowing licensees to provide a full suite of banking services entirely through digital means. Easypaisa is among the first recipients of this licence, while JazzCash has also shown interest in pursuing a digital bank licence in the future.

With Easypaisa’s shift towards digital banking and JazzCash’s likely pursuit of similar capabilities, the future of branchless banking in Pakistan appears to be at a critical juncture. Easypaisa’s digital banking licence will enable it to extend lending services beyond the limitations imposed by microfinance regulations. This transition will likely see Easypaisa’s transactions categorised under digital banking, potentially reducing reported branchless banking volumes even as underlying transactions persist.

Digital retail banks are expected to begin operations by 2025, with Easypaisa among the first to launch. JazzCash’s future will depend on whether it secures a digital banking licence, and until then, it will continue to operate under its branchless banking framework. The dominance of telco-backed platforms like JazzCash and Easypaisa has proven pivotal for financial inclusion in Pakistan, but new entrants and regulatory changes may redefine this sector.

As Pakistan’s financial sector evolves, the question remains: will branchless banking adapt to become a subset of the digital banking ecosystem, or will it eventually become obsolete in favour of fully digital platforms? For now, branchless banking continues to bridge financial access for underserved populations, but its place in the future is likely to change as digital banking takes root. n

By Zain Naeem

In the leadup to the 2023 budget, the halls of Q-block were buzzing as employees of the finance ministry did their best to try and outdo each other. Their task was very simple: finding ways to collect as much tax as possible. Among the many ideas floating around, one that snuck past everyone and made it into the budget was the idea of taxing bonus shares.

The taxation rules were changed in 2023. The example of Mari Petroleum’s recent bonus share tax meltdown is telling of how well the changes have taken root

Either no one realised the chaos this would unleash on the stock market, or no one cared.

Nothing illustrates this better than the recent dividend declaration made by Mari Petroleum along with their annual financial statements. In fact, what has happened to Mari shows the idea to impose this tax on bonus shares is poorly implemented at best and ill conceived at its worst. The law ensures investors and companies are saddled with excessive burden, and we now have a solid example of investors facing losses because of this plan.

So what exactly happened over at Mari? To start off, we need to understand how bonus shares work.

Bonus shares are shares that are given out by the company to its existing shareholders in order to attract investment and to reward the shareholders. The bonus share is given against the

company’s earnings or reserves that are accumulated by the company over time. This issue increases the share capital of the company and the number of shares circulating in the market without increasing the market capitalization. The shares given out do not dilute the ownership of the shareholders.

Companies carry out bonus issues in order to lower the price of the share and promote investment and liquidity in the stock. Research has shown that as the price of a stock rises, the participation and hence the liquidity in the share decreases. In order to encourage investment, bonus shares can be given which slash the price of the stock. As the price falls, shares become more affordable and easier for investors to trade in. The shareholders can buy more shares which pumps more liquidity and interest in the market.

Bonus shares are also given out in order to reward the shareholders when cash dividends cannot be announced. The company might want to hold onto cash for its own needs and allots a portion of its reserves for this purpose. Companies are always looking to maintain cash within the company. As an alternative, they can use these bonus shares to reward the confidence of the investors. Bonus shares are also beneficial as they showcase the strong financial position of the company and shows that the company is financially stable.

One of the biggest advantages of a bonus issue is that it is not taxed. Nowhere in the world is such a dividend or entitlement taxed and is considered one of the reasons that companies are encouraged to give out bonus shares rather than maintain it within the company or give out cash dividends. Maybe that is why it was considered a good avenue to generate tax revenues from when Q-block devised a manner to tax it. But the fact that these shares are not taxed has a very good reason behind it. Bonus shares do not add any value.

When a bonus share is announced, the investors do not gain anything from such a move. On one hand, the shareholders see their shareholding increase while on the other, they see the price of the share fall by the same amount. In real terms, the value of their investment stays the same. An investor who held 100 shares at Rs 10 before the bonus of 100% would see his shares rise to 200 shares but the price per share will fall to Rs 5. Similarly, the company only sees its number of shares increase on its balance sheet and moves the value from its reserves to its issued share capital. The numbers are moved around with no implication on the assets and liabilities of the company. No cash or value has been realised and the taxation being carried out cannot be determined based on a value that is notional rather than actual. There is a reason

why bonus shares are not taxed anywhere in the world. The all knowing Dar failed to realise this and passed this into law.

The logic behind keeping bonus shares tax free is due to the central tenet of bonus shares. The shares do not add any value and are not providing any beneficial gain to the shareholder or the company. Bonus shares are used for capitalization of profits which means that the reserves of the company are being utilised to increase the share capital of the company. No inflow or fresh funds are injected into the company which means that no additional income or cash flow is being generated which needs to be taxed. The shareholders are not receiving any benefit from this issue as their investment is still considered to have the same value before and after the bonus shares are credited.

As the shareholding of the investors also stays the same, no transfer of value or property is being carried out which would alter the wealth of the shareholders. There is also a perception that the shareholders are actually getting two benefits from bonus shares being given. The investor has the ability to sell additional shares and they can sell them whenever they want leading to additional value in the future. This rationale is again flawed. In terms of being able to sell at a later date, the investor is liable to pay capital gains tax on these shares once he realises a profit. As some value has been gained after the bonus share, it is taxed and there is no need to tax the bonus issue before that fact.

The

2023 taxation rules started seeing both cash dividends and bonus shares as income from other sources. This would mean that if the company gave out a cash dividend, the Federal Board

of Revenue (FBR) could expect to see a tax of 15% on this dividend. In case a bonus share was given, the FBR could expect 10% of the bonus share to be collected in the form of tax. This came in continuation of Dar and his tax policies from 2014 where it was felt that companies were able to use this loophole and give out bonus shares rather than cash dividends. There were also plans to tax the undistributed reserves and profits that companies had accumulated on their balance sheets and there were suspicions that companies would start giving out bonus shares in order to avoid this tax. Sadly, the 4D chess that the dear minister was playing went against basic logic and the impact of this decision is slowly dawning on the market.

So what does the law actually state? Section 236Z of the Income Tax Ordinance 2001 states that bonus shares declared by the company shall be liable to pay ten percent of bonus shares which are to be withheld by the company itself. These shares are only to be released to the shareholder once they have deposited the amount of tax which is obligated on them. Once they do so, the shares are released to them by the company which had been frozen previously. In case the shareholder does not deposit the tax, the company has the authority to sell these bonus shares and, based on the funds generated from the sale, collect the tax that has to be paid by the company. The company has 15 days from the date of book closure to deposit this tax with the FBR whether the shareholders have paid this tax or not.

When this law was proposed and passed, there were critics who had already started to see how this tax was not well thought out and did not pass the smell test in terms of accounting norms and standards. Shabbar Zaidi wrote an article lambasting this taxation policy as it was taxing based on

notional value which was determined in the market. The whole concept was absurd as it meant that FBR was expecting the companies to collect tax on value that had not been realised. The law had been designed with little understanding of the subject and could not be implemented in its previous form from 2014 to 2018. The new incarnation of it was going to face similar backlash and would be rejected by the business community. Whenever it was implemented in the past, the matter was stayed by the courts as well.

Market value of a share is based on future expectations and market sentiment of a share. Basing any taxation on this value would mean that shareholders are expected to deposit a tax which they have not earned or realised. Taxing bonus shares also falls under the purview of double taxation as it would mean that bonus shares are taxed initially when they are given and then these same shares will also be subject to capital gains tax being applied when they are sold. The investor is expected to cough up the withholding tax on the bonus shares initially and then capital gains tax when they are sold. The double whammy in this case is that bonus shares are considered to be acquired at Rs 0 which means all sales proceeds on these shares fall under the gambit of 15% capital gains tax.

The Pakistan Business Council (PBC) also felt this section of the Income Tax Ordinance needed to be scrapped as it is a taxation on unrealized gains of the shareholder before any gain is realised. Their advice was not heeded and the Federal Budget for 2024 was passed with no such action being taken

Even if it is considered that the taxation should be carried out, the mechanism devised by the lawmakers is problematic. First of all, the taxation is being carried out on market value rather than the face value of the share which is mostly higher leading to extra burden on the shareholders. Another complication that has been added in the law is that the market price being used for determination of tax is to be the first day of book closure of the company. This is where Mari Petroleum comes into the picture.

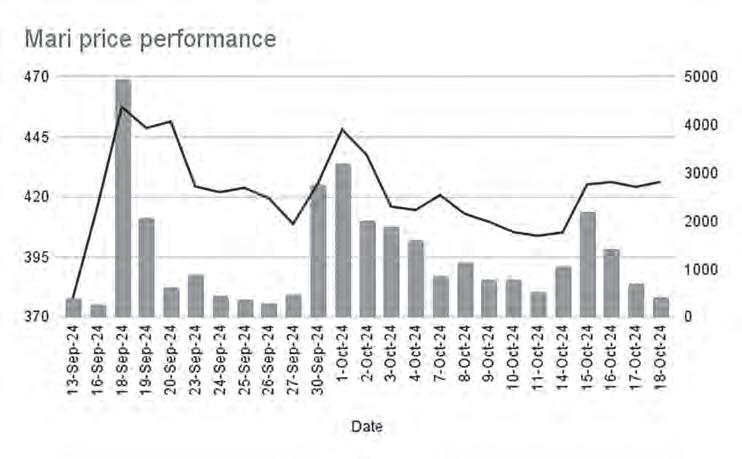

On 8th of August 2024, Mari released its financial accounts. Based on this, its board announced that they were going to recommend a cash dividend of Rs 134 per share and a bonus issue of 800% to its shareholders. This would mean that each shareholder was going to get Rs 134 and 8 shares for every share that they held. The date for book closure was determined to be 19th September to 24th of September. This meant that for any shareholder who had the shares on 13th, they would be entitled to get

the dividend and shares. When the market opened on the 16th, the share price of the company had gone from Rs 3,536.83 to Rs 378. From 16th to the 19th September, the stock saw its price increase upwards and close at Rs 448.71 on the 19th. Under law, Mari was expected to collect 10% of the bonus shares that they had given at Rs 448.71 per share. On 24th September 2024, the shareholders resolved to give out the proposed entitlement to their shareholders. By 26th, the cash had been sent to the bank accounts and by the 27th, the shares had been sent to the shareholders.

On the day the shares were sent, the share price of Mari hovered between Rs 422.97 and Rs 407.5 closing at Rs 408.83. Many of the investors started to sell the additional shares as they were able to realise a profit of Rs 30 per share on the 8 shares they had received. On the 30th of September and 1st of October, this trend increased as the share price had touched Rs 448 by the 1st. By now, it dawned on the management at Mari that the share price of the stock was volatile and mostly trading below Rs 448.71. This meant that shareholders would not pay the withholding tax as they can get the same shares at a much cheaper rate from the market. This would mean that the company would be liable to pay the tax out of its own pocket rather than collecting it from the shareholders. This is the problem that has been codified in the bonus share taxation law. It sets an arbitrary date for determination of the market price rather than anything concrete. Once the shares start trading, the price keeps changing and the company has no control over it. Shareholders have the option to either pay the tax or let go of these shares if they can get the shares at a cheaper rate in the market. The company is left on the hook and has to pay the tax even if the shareholders have not done so.

The management at Mari approached the Islamabad High Court which directed the Central Depository Company Limited (CDC) to freeze an additional 10% of the shares of filers and 20% of the shares of non-filers. Mari contended that once the recovery of the full taxation amount was done through the shareholders or the sale of the withheld bonus shares, the extra shares would be released to the shareholders.

In normal circumstances, an investor sells his shares in the market and then these shares are cleared and settled in two days’ time. For shares sold on Monday, the amount is credited to their account on Wednesday and the shares are taken away on that day. The order that the court passed was able to provide relief to the company. However, it led to financial losses for the investors. Investors had sold their shares on the 30th of September and 1st of October which would have been

settled on 2nd and 3rd of October. When the court placed a freeze on these additional shares, these shares were not settled as they would have been settled under normal circumstances. The sellers were not allowed to sell these shares. But normal functionality of the market has to be guaranteed. The ones who bought the shares from these sellers need to get these shares. They could have further sold these shares and need to fulfil their own settlement needs. In order to make sure the system does not collapse, sellers were mandated to provide these shares.

The market presumed that the sellers did not have the shares and had shorted them which is not allowed. The remedy that the market has devised for this is to penalise the sellers Rs 2,000 for the trade and then force them to buy these shares in the Square Up market from someone who actually has the shares. The financial burden of this is that the square up and another investor who has the shares can charge up to 30% above the price being traded in the market. The sellers had to buy at these higher prices, pay a penalty and be liable for the delivery of these shares for a decision that had been passed by the courts.

In addition to having to pay these additional costs, they might still have to pay the tax at a higher price in order to get their frozen shares back as well. The investor will bear all these costs while the problem will stay on the books as it is not addressed.

The last date to pay the tax was set at 15th of October which has come and passed. Currently there are investors who paid the tax and have not received their shares. The company has little it can do as it would want to avoid paying any tax from its own pocket. The shareholders will look to avoid paying any tax as the price on the 15th was at Rs 425. In the end, the law would mandate a pound of flesh to be extracted from the company and the investors on a law that should not even be on the books in the first place.

The remedy for this situation is to scrap the tax on bonus shares altogether. FBR already has mechanisms in place which tax the shareholders. Cash dividend is charged 15% in withholding tax and it has been earned which allows for this tax to be collected. Bonus shares are being taxed at 10% which should not take place as it is a tax on a notional value. Once the shareholders sell these shares and make a profit, the profit is taxed as capital gains tax. Bonus shares will always yield a profit as the cost associated with bonus shares is always considered to be zero meaning all sales proceeds are considered profits. In the case of Mari, it has also been seen that investors can lose out additionally once the company goes to take legal recourse in order to protect itself which hurts all the market participants. n

Here’s what it means for your monthly grocery bill

GMO soybeans are an efficient source of edible oil but more important poultry feed, and their import could mean a reduction in chicken prices

The federal government has approved the import of genetically modified (GMO) soybeans, granting licenses to 39 companies. This landmark decision aims to support the poultry sector, which relies heavily on soybean as a protein source for feed.

It is a big win for soybean importers in Pakistan, who have been running from pillar to post trying to have their imports approved by the government. In Pakistan, nearly 90% of the import of oilseeds is constituted by palm and soybean oilseeds. In a special report for the financial year 2022, the State Bank of Pakistan included a section on rising palm and soybean imports. According to the report, Pakistan’s palm and soybean-related imports stood at $4 billion, rising by 47 percent year-on-year, compared to compound average growth of 12.3% in the last 20 years.

The share of soy and other oilseeds in this has been growing. There is a clear indication that as people climb social and financial brackets, their preferences change towards cooking oil over Vanaspati Ghee, which is the main source of cooking oil used in Pakistan. Edible oil consumption in Pakistan has increased significantly over the last few decades: from 0.7 to 4.7 million tonnes between 1981 and 2020. The main demand drivers are rising population, dietary preferences and increase in per capita income. According to the recent SBP report: Pakistan’s per capita edible oil consumption is already higher compared to economies with similar income levels.

In addition, increasing income levels may also translate in increased per capita consumption of edible oil, as will population growth. According to the UN’s World Population Prospect 2019, at constant-fertility, the country’s population in 2025 is set to reach 245 million, and 328 million by 2040. This implies that demand for edible oil will continue to increase noticeably. According to estimates by the Pakistan Oilseed Department, total demand for edible oil in the country is conservatively expected to grow to 5.9 million tonnes in the fiscal year ending June 30, 2026, from 4.7 million tons in fiscal year 2021.

And that is not all. There is another major advantage to oilseeds such as soy. In the solvent extraction process in which these seeds are pressed, the remaining material that is left after the oil is extracted is highly nutritious. This material is then used to create “meals” which are fed to poultry. In the three decades since 1990, the consumption of oilseed meals as feed for livestock has tripled in the country – a big reason for which is the growth of the poultry industry. Just think about it. If you remember a time before the 1990s, chicken was not the cheapest protein available and the poultry boom only came later.

Soybean meals are apparently especially good for the poultry industry. Since it is rich in nutrition, its meals offer better digestibility, quality mix of amino acids and have the highest protein content (around 44-50%) compared to all other oilseed meals. These qualities make it a better feed ingredient for chicken in comparison to cottonseed – which was the traditional oilseed used in Pakistan.

However, sinc the winter of 2022, soybean imports have faced faced some serious challenges.

To cut a very long story short, It all started with a technicality — but a technicality that was being ignored for a few years. On October 20, 2022, two shipments were stopped at Port Qasim in Karachi. The shipments contained GMO oilseeds worth some $100 million on board. And despite the very vocal protestations of the importers that had paid for the consignments, they stayed stuck at the port pending a single certification from the ministry of climate change. The climate ministry was concerned that the oilseeds were GMOs. In the months that followed, more vessels joined the two stuck at Karachi and the value of the oilseeds piling up at the port grew over $300 million.

Now, it is worth pointing out here why the shipments of GMO oilseeds were stopped. There is a general fear of GMOs in many places across the globe, fears that are completely unfounded and not based in any scientific research.

Even though the scientific evidence is overwhelmingly in the favour of GMOs, the public perception of GMOs is unfavourable. This is mostly coming from the same brand of pseudo-science that promotes homoeopathic remedies over actual, tested, medicine that

works and peddles crystal therapy and all manners of snake-oil.

GMOs are safe by all accounts and nothing to be feared. Despite this, their acceptance in Pakistan is low. When the oilseed shipments in Pakistan were stopped in 2022, it was followed by a huge ruckus raised by then food minister Tariq Bashir Cheema, who announced he would suggest people stop eating chicken because it was “toxic”. These unfounded fears have caused more harm and confusion than anything else.

In December 2023, the government actually made changes in Pakistan Biosafety Rules to include provision for GMO grain imports. It seemed sense would prevail after the ugly business, but since then the EPA has been taking an excessive amount of time to process applications and has not given approvals.

Finally, however, these imports have been allowed.

The Pakistan Poultry Association (PPA) welcomed the move, describing it as crucial for maintaining steady protein supplies, especially after a prolonged ban on GMO soybean imports. The National Biosafety Committee (NBC), alongside other government bodies, led extensive consultations before finalizing the approval process. All of this will also help the poultry industry, where prices saw a direct and sharp increase. It also helps extractors, who will be able to do much better business. In fact, cheap feed has been a hallmark of the poultry revolution.

Starting in around 2000, the local poultry industry had made remarkable investments in its value chain. This was followed, in 2015, by a change in the feed formulation to a corn-soybean diet which resulted in significant gains in the Feed Conversion Ratios (FCR, the ratio of feed consumed and bird weight achieved). The net impact of these remarkable initiatives was a significant decline in poultry products’ prices in real terms, making chicken meat and eggs the cheapest protein sources in the country. For comparison, a kilo of chicken meat which cost more than a kilo of beef prior to 2000, hovered at less than 40% of the cost of beef over the last decade. The poultry industry was devastated by the unavailability of soybeans resulting in steep rise in poultry prices. The local corn crop has also been affected by this crisis as poultry was the main market for it.

The inability to get these GMO oilseeds has serious business implications for soybean extractors. The average premium for non-GMO soybeans is around $150 per ton. So if the market is 2 million tons, the total yearly impact is around $300 million. Furthermore, higher cost of poultry resulting from 30% higher soybean meal cost kills demand which further affects the feasibility of poultry farming. Only 12% of Pakistan’s edible oil demand is met through indigenous sources. In the absence of soybeans, we end up importing more soybean oil and lose

the opportunity to have value addition in the country by importing raw material instead of finished products.

The permission for the import of GMO soybeans is a good sign and has taken repeated lobbying efforts with government functionaries that are often slow on the uptake. However, stakeholders should continue to be cautious.

decision follows ongoing debates and opposition from several governmental factions, including the Ministry of Climate Change and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Some officials remain wary, expressing concerns about the potential entry of GMO seeds into local agriculture and the implications for Pakistan’s non-GMO status.

Industry insiders noted that the previous restrictions severely impacted the poultry sector, with over 60% of industry players contracting or closing operations due to high feed costs.

With the new licenses in place, companies are now better positioned to stabilize feed supply chains, which could lead to more competitive poultry prices in the market. n

In CCP hearing, Zong claims PTCL’s acquisition of Telenor will create an uncompetitive environment. Why do they say that?

By Ghulam Abbas

The Rs108 billion deal for Pakistan Telecommunication Company Ltd (PTCL) to acquire Norwegian telecom giant Telenor’s Pakistan operations continues to languish in limbo as the Competition Commission of Pakistan (CCP) hears a complaint made against the acquisition by PTCL’s rival Zong.

In a hearing on Wednesday, Zong raised objections to the acquisition, arguing that it could significantly distort the competitive landscape of Pakistan’s telecom sector. Zong contended that PTCL, which also owns Ufone, would have a combined market share of 36.5%. The current market leader is Jazz, which has a 37% share and the acquisition would throw Zong into a distant third place acquisition of Telenor’s Pakistan business would push the combined company’s market share to 36.5%, close to Jazz’s 37% share, leaving Zong at a distant third place with just 25.6% of the market. At the heart of the case is the issue of spectrum allocation, a key determinant of telecom companies’ ability to offer efficient mobile services. During the hearing, government officials informed the CCP that if the deal were to go through, the merged Ufone-Telenor entity would control 34.4% of the total spectrum allocated in Pakistan. Spectrum, which is a limited and highly regulated resource, is essential for maintaining service quality and network coverage. Zong’s representatives argued that this consolidation would create a duopoly in the telecom market, drastically reducing competition. The CCP is now tasked with deciding whether such a concentration of market power is permissible under Pakistan’s competition laws, or whether it would harm consumers by reducing the incentives for competitive pricing, innovation, and service quality.

Behind this entire story is another concerning tale: Telenor’s decision to exit from Pakistan. A Norwegian company, Telenor entered the Pakistani market in 2005, investing over $2 billion in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) over the years. However, the Norwegian telecom giant’s decision to divest from Pakistan is part of a broader restructuring of its Asian operations.

In 2023, Telenor merged its Thailand and Malaysian operations with local companies, creating larger, more profitable regional units. A similar attempt was made in Pakistan, but the Norwegian firm was unable to finalize a local merger. “We also tried to do a merger in Pakistan, but we didn’t manage to get that, and when we saw this wasn’t happening, the second-best alternative was to arrange a sale,” said Telenor CEO Sigve Brekke when the sale was announced in December 2023.

Brekke explained that the decision was driven by both structural challenges in the Pakistani market and the need to maximize value for Telenor’s shareholders. In the first nine months of 2023, Telenor Pakistan contributed 2.6 billion kroner ($247 million) in service revenue and 1.4 billion kroner ($133 million) in earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) to the Norwegian group. Yet, these figures weren’t enough to justify a continued presence in the country, given the company’s broader strategic realignment in Asia.

Telecom companies in Pakistan have one of the worst average revenue per user (ARPU) in the world, at $0.8/month and for the Norwegian company, ARPU was a big concern, considering that other subsidiaries of the Telenor group in countries like Malaysia, Thailand and Bangladesh were doing much better. Telenor entered the Pakistani market in 2005 and over the years managed to amass a subscriber base of approxi-

mately 45 million customers. However, operating in a highly saturated market presents its own challenges. One such challenge is the steady decrease in ARPU, which is a concern for the entire industry.

The company restructured its operations to focus on low-value customers who primarily demanded voice and SMS services. With the rise of 3G/4G services and OTT apps like WhatsApp, Telenor began losing its stronghold in voice and SMS services and eventually exited the Indian market in 2017. The events leading to Telenor’s decision to exit the Pakistani market closely resemble what happened in India.

If the deal goes through, PTCL, which already owns the Ufone mobile network, would acquire Telenor’s 45.2 million customers. Combined with Ufone’s 25.2 million subscribers, this would give PTCL over 70.4 million users in Pakistan, nearly equal to Jazz’s total number of subscribers.

However, contrary to some claims, it is also important to address that despite being closely integrated with Telenor Pakistan, the leadership and ownership of Telenor Microfinance Bank and, by extension, of Easypaisa remains the same. The bank as of now is jointly owned by Ant group (Alibaba) and Telenor’s Norwegian parent company. It was made clear by the PTCL leadership that the Share Purchase Agreement referred to the operations of Telenor, the telco alone. With the previous ownership structure, Telenor Microfinance Bank enjoyed cross-marketing and other preferential pricing like the SMS costs for transaction prompts on USSD supported easypaisa accounts. These are likely to be discontinued/ However, the Telenor Group will still retain its ownership of the digital bank unless announced otherwise. n

refill

$120,000

startup, has a

grant from the World Bank.

What are they using it for?

Davaam’s whole thing is sustainability. Their immediate plan is to reduce plastic waste and fight period poverty

By Nisma Riaz

Three years ago, when Profit first covered Davaam, the sustainability-focused startup was aiming to revolutionise waste management and install innovative refill stations, hoping to convince multinational FMCGs to embrace a more environmentally conscious approach to packaging.

It was the kind of plan that hopes large companies manufacturing products such as

shampoo will encourage their customers to refill their bottles (and save a little money in the process) instead of buying new ones. They were banking heavily on their refilling stations.

Three years later, this plan has failed to materialise. In case you have not noticed, there are not any refilling stations offering these services, or any companies advertising their products at refilling stations.

Yet Davaam is alive and kicking.

The company has evolved into something far more ambitious; a technology company that’s finding unexpected success in industrial

solutions, private labelled products for refilling old plastic bottles and corporate partnerships for its sanitary napkin vending machines.

So what is Davam doing now, after big MNCs closed their doors on their face.

The original idea behind Davaam to create circular economy initiatives in order to manage wastage in society. They launched a refilling machine

in their store in Karachi where customers can bring their shampoo bottles and refill them at a discounted price in 2021. It was an idea that intuitively makes sense, and in the initial days, Unilever also showed interest in their design. But over time their strategy has changed.

Salman Tariq, co-founder & CEO of Davaam, reflecting on Davaam’s journey, described a fundamental shift in their approach to sustainability. But what necessitated this shift?

When Davam initially developed their refill station technology, they were faced with roadblock. “We had made a machine, but who had the products? Unilever, Procter & Gamble, Reckitt Benckiser,” Tariq said, answering his own question.

“Our initial model was to make the machine and partner with these large companies because they have the products. But what happens when none of these companies want to invest in my machine?” Tariq asked.

The answer? They are left with shiny technology that just sits and collects dust.

This realisation forced another crucial pivot. Rather than waiting for major FMCGs to adopt their technology, Davaam began contract manufacturing its own products, such as liquid soaps and even cooking oil. “Making hand wash is not rocket science. You can make it at home,” Tariq pointed out. “These companies have brainwashed you with advertising that makes you believe your hands won’t be clean unless you wash it with their product.”

What’s interesting is that these big brands themselves rely on contract manufacturers. Tariq revealed, “So we went directly to the best local manufacturers and commissioned them to create products matching top-tier quality standards. We said, ‘Make us a surface cleaner, hand wash, and dishwashing liquid that can compete with the leading brands.’”

They claim to be not cutting corners, having everything tested by Pakistan Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (PCSIR). Tariq emphasised, “If we tell you that our hand wash kills 99.9% of germs, produces the same foam quality, causes no skin irritation, and has the same appealing fragrance as leading brands, why would you not buy it? The only real difference is that our products cost 40% less.”

So the question becomes simple, if you can get the same quality of products, verified by laboratory testing, at nearly half the price, would you still need the big brand name?

The answer, at least for the average Pakistani, is a resounding no. They genuinely do not care, when it looks and feels the same, while also saving them money.

“What makes our business model unique is that we’re not just a hardware company,” Tariq noted, adding, “Think of it like a printer company that also supplies the ink. We’re handling everything from manufacturing and

maintenance to product distribution. We’ve become an all-in-one tech-driven distribution company.”

The current model has proven far more sustainable than simply selling machines. Tariq explained, “A one-time sale doesn’t generate recurring revenue. But by focusing on both the technology and the products, we’ve created a continuous income stream.”

They are predominantly focusing on products towards which they believe people are brand agnostic, “We’re very strategic about our product selection,” he added. “We focus on categories where brand loyalty isn’t strong, things like dishwashing liquid, surface cleaners, and hand wash. We’re not attempting to compete in categories like shampoo, where consumers are particularly brand-conscious.”

He noted that Davaam’s partnership strategy has also evolved based on experience. “We’re working with companies like Co-Natural, a Lahore-based firm that was actually our first pilot partner three years ago. Initially, we thought major multinational corporations would be our ticket to success since they invest heavily in innovation. But we’ve learned something surprising, local companies are actually more enthusiastic about embracing innovative solutions than their multinational counterparts.”

Davaam has now evolved from waste management to waste prevention, and from technology provider to full-service solution. By controlling both the distribution technology and the products being distributed, Davaam has created a model that doesn’t rely on the cooperation of multinational FMCGs to make an impact.

Davaam’s funding journey is not a smooth one. “We were two entrepreneurs that bootstrapped since 2017,” Tariq recalled. “We were two sustainability fanatics, who for the first five years bootstrapped everything and all the experiments that we did related to solar and waste management were from our own money.”

Their first significant funding came in 2021 when they won the Karandaaz green challenge fund, securing a concessional loan of around Rs 50 million. This initial funding allowed them to properly fund their R&D activities and develop their machines. “The challenging part was that we had to build our R&D capabilities primarily through loans. Even though they were concessional loans, they still needed to be repaid, and building an R&D-based business on loan funding isn’t ideal. That pressure was significant,” Tariq admitted.

“However, we’ve managed to emerge from this financial challenge successfully. Now we’re seeing interest from multilateral development institutions and donor agencies. We’re even in promising discussions with foreign equity investors, despite the currently constrained investment climate.”

More recently, they received an innovation grant of $120,000 from the World Bank and UNOPS.