08 Dear control-freak seth, welcome to the stock exchange

14 The landmark IHC ruling that could change how Pakistan’s pharmaceutical industry works

19 There is a bidding war for a loss making fertilizer plant. But why?

23 After pandemic losses, Pearl Continental is well on the mend. But did their problems run deeper?

27 Round two: Mitchell’s back on the market

28 Pakistan has proven cricket can be profitable without India. That’s why we can afford to snub them

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz Khan - Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Editorial Consultant: Ahtasam Ahmad - Business Reporters: Taimoor Hassan | Shahab Omer

Zain Naeem | Saneela Jawad | Nisma Riaz | Mariam Umar | Shahnawaz Ali | Ghulam Abbass

Ahmad Ahmadani | Aziz Buneri - Sub-Editor: Saddam Hussain - Video Producer: Talha Farooqi

Director Marketing : Mudassir Alam - Regional Heads of Marketing: Agha Anwer (Khi) Kamal Rizvi (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) - Manager Subscriptions: Irfan Farooq

Pakistan’s #1 business magazine - your go-to source for business, economic and financial news. Contact us: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

By Zain Naeem

After decades of being considered, it is finally here. Dual class shares are being allowed for publicly listed companies on the Pakistan Stock Exchange, and Mughal Steel has decided to jump into the fray by announcing the existing of what they are calling “Class C” shares, which will not be tradeable, not eligible for dividends or bonuses, but will have 50 times the voting power of ordinary shares listed on the exchange.

Needless to say, this move is expected to be highly controversial, and many people – especially the handful of advocates for the rights of minority shareholders – are likely to be deeply upset by this development.

So why is the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP) even allowing such a thing to exist, whose explicit purpose is to reduce the power of minority shareholders and give insiders even more control over the companies they run?

Because there is more to dual class shares than meets the eye, and while it certainly has its downsides, it has benefits which the regulator is likely keen to see realized.

In this story, we will examine what dual class shareholding is and what its benefits and downsides might be, how it is done in other parts of the world, and then finally how it applies to the case of Mughal Steel.

What is dual class shareholding?

Consider the position of the Pakistani seth. After spending years of toiling and building up their business, in the naysaying culture of Pakistan that does not exactly encourage entrepreneurship, they want to make sure that they control every aspect. The seed that they nurtured and cared for has grown into a flourishing tree and they want to make sure they get to enjoy the fruits that they bear. In the case of companies that have managed to stay documented, they have even gone to the trouble of following all the rules while being treated like a criminal by the government at every turn.

But what happens when they want to get additional funds and capital to keep growing their business further. Either they have to head to the bank and ask for a loan – which Pakistani banks do not like giving to them unless they already have collateral worth much more than what they want to borrow – or they can go to the capital markets to raise the necessary funds. Once the banks have been maxed out (which does not take very long), the only option they have left is to head to the stock

exchange and issue shares of their business.

For many, the issue is not even about sharing profits. Investors who have invested in the business should get to share in the profits that are being earned and Pakistani business owners are no different from business owners all over the world in understanding that concept. The one thing that sticks in the seth’s craw is the fact that they have to give over some of the control over to these shareholders.

Shareholders get two things when they invest their money into a company. Firstly, they have a claim to a share of the company’s profits, particularly when they are paid out in the form of dividends. The second right, not one many retail investors often think about, is that they get to vote on important matters brought up before a vote of shareholders (including how much to pay out in dividends, and who to hire as CEO, being two of the most important). It is this voting on important decisions that can sometimes result in acrimony between the founding family and their minority shareholders.

With a dual class shareholding, there is no change to the claim investors have to the profits of the company, especially not to dividends and bonus shares. There are usually substantial changes to the voting rights, however. More specifically, a separate class of shares is created which carries more votes per share compared to ordinary shares.

In the case of Pakistan, there are other considerations, particularly some regulations that have tried to increase the number of shares available for trading for each company listed on the stock exchange.

In order to get listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange, the minimum initial public offering is expected to offer up 10% of the shares of a company to the public. The exchange then requires companies to increase their floated shares to at least 25% over time. Section 5.4 of the PSX Rulebook states that in case the offering is up to Rs2.5 billion, the listing company should initially offer 10% of the share capital and then increase it to 25% in a span of three years.

That 25% number is particularly important because under Pakistani corporate law, a 75% majority is required to appoint the CEO, which, as Asad Umar used to say when he was the CEO of Engro, is the single most important decision the shareholders can make. If a company floats 25% of its shares to minority shareholders, it needs absolute unanimity among the founders or family shareholders in order to ensure that they retain control over the decision to have their own CEO. For this reason, the 25% plus one threshold is called “negative control”, meaning that it gives minority shareholders a veto on an unacceptable CEO if all of them band together.

The giving away of power and control

is a big reason many companies choose to stay private. The two others are a desire not to share information about the company, and a desire not to share the profits. The exchange can do nothing about the latter two: after all, that is the very point of being listed. But they are betting that many Pakistani companies do not mind sharing information and profits, as long as they get to keep complete control, and that the founding family can never be ousted from controlling their company.

That is why the dual class shareholding is likely being allowed by the exchange, with the blessing of the regulator.

Dual class shares around the world

This may be a new concept in Pakistan, but how does the rest of the world handle it? Broadly speaking, the world’s markets are divided into three camps:

1. Allowed completely: United States, Sweden, and the Netherlands

2. Allowed with restrictions: Singapore, Hong Kong, Canada, India, and China

3. Banned completely: United Kingdom, Australia, most of Europe and Latin America

Needless to say, there is far from a consensus on how to approach this matter, and different countries have arrived at very different conclusions on what is the most appropriate set of rules. Based on what the SECP and PSX appear to be allowing, Pakistan’s approach appears to be somewhat similar to the United States than the other two approaches.

Since the United States accounts for more than 45% of the total market capitalization of all stock markets in the world, and is generally considered the most sophisticated of the world’s capital markets, it may be pertinent to ask: how are things done in that market?

In the US, dual class structures are becoming more common, especially among technology and media companies. They allow

founders and insiders to maintain control with a minority economic stake. About 7% of the Russell 3000 – an index of the 3,000 largest publicly listed companies in the United States – have some form of dual class shareholding structure.

Even in that market, however, they are not without controversy, with critics arguing they reduce accountability to shareholders. Proponents say they allow long-term focus and protect from short-term market pressures.

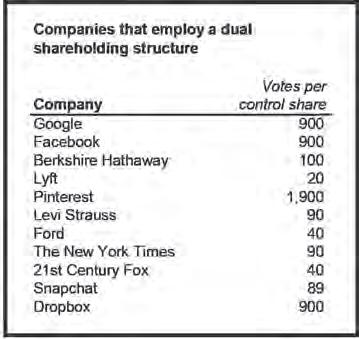

Many of the most famous companies in the world employ a dual class shareholding structure, including Google, Facebook, Berkshire Hathaway, Levi Strauss, The New York Times Company, and Ford Motor Company. Equally famously, however, many companies do not, such as Tesla, Amazon, and Microsoft. In the case of Microsoft, Bill Gates has publicly stated that he was opposed to the idea of a dual class shareholding that would have given him more power over the company.

The Mughal Steel transaction

Mughal Steel is creating a separate class of shares that would give its founding family significantly more control over the company. They are creating a set of Class C shares that will have 50 votes per share, and issuing 50 million total shares, which would give these shares 2.5 billion votes. The company only has about 336 million ordinary shares, so these Class C shares would exercise 88% of the votes in any shareholder vote, and hence have complete control over all matters in the company.

It appears that this new class of shares being created is not being exempted from the requirement of being offered to all shareholders, which means that the sponsors of Mughal Steel have had to come up with a way to ensure that outsiders will not want to buy these shares: Class C shares will not receive any profits or dividends from the company.

Since the shares are not eligible to receive

dividends, they are being issued at a substantial discount to the current market price per share of the stock, which closed at Rs70.51 per share at the close of trading on the Pakistan Stock Exchange on Friday. The Class C shares are being offered for Rs30 per share to the controlling family (technically to everyone, but likely only the sponsors will be bidding for them).

At that price, the sponsors will pay Rs1.5 billion to acquire 88% of the control of a company valued by the market at Rs23.7 billion as of the close of trading on Friday.

What is somewhat perplexing is that the Mughal Steel sponsors do not appear to need much by way of additional control. Between their direct family holdings and those they own through other companies in which they have controlling stakes, the sponsors control about 75.4% of the company already.

But perhaps 75% of the votes – and full control over the board and CEO hiring decisions – is not enough for the sponsors. After the issuance of the Class C shares, minority shareholders will have 24.6% of the shares but just 3% of the votes at annual general meetings and any extraordinary shareholder meetings.

The official use of proceeds is to finance the working capital of the company, which effectively means there is no specific use in mind other than the cash being made available for the day-to-day operations of the company. There appear to be no growth or expansion plans being funded by these funds, based on the draft offering document released by the company.

The company does have approximately Rs28 billion in short-term debt, though the bulk of that debt appears to go into financing the company carrying about four months of inventory on its balance sheet.

The Mughal story

Mughal Steel itself is a company that has a long history, having been founded in 1950 as a steel trading company (unincorpo-

rated for most of its early existence) called Mughal Traders. It is currently the largest manufacturer of long rolled iron and steel products in Pakistan.

Through the years, that sole proprietorship kept on growing and becoming more and more formalized, providing some evidence for the hypothesis that the Pakistani informal economy will automatically formalize when the barriers to growth start getting removed.

In 1994, a steel production unit called Al-Bashir Steel Industries (Pvt) Ltd was established on the outskirts of Lahore. The company installed a melting unit along with medium section re-rolling mills to produce residential and structural sections like I-beams, H-beams, C-sections, L-sections etc.

In 1998, Mughal Steel – by then a partnership – was established. In 1999, Mughal Steel imported and established two induction furnaces. In the same year an Argon Oxygen Decarboriser (“AOD”) was installed along with ladle refining furnace reaching a complete melting, refining alloying cycle. AOD was the first of its kind in Pakistan, capable of producing stainless steel of high quality.

In 2003, a stainless steel sheet rolling mill was added to the previously established Mughal Steel. The new production unit resulted in increased product line and efficiency. To compliment several production units and ensure quality standard Mughal Labs (“ML”) was established. ML is equipped with chemical and mechanical analytics machines as well as an optical emission spectrometer.

In 2006, foreseeing the rising demand of electricity, Mughal Steel set up a 9.3 MW captive power plant. In 2007, Mughal Ferros was established. The project was aimed at utilizing existing deposit of manganese and chromites in Pakistan for the formation of alloys such as ferro manganese and ferro chrome. It is used for reducing metals from their oxides as well as for deoxidizing steel and other ferrous alloys.

In 2008, Mughal Steel took over the

plant and machinery of Al-Bashir Steel and installed two additional mini sectional mills.

By 2010, the company formally converted from a partnership to a private limited company. In the same year, the company installed a bar re-rolling mill with capacity of 150,000 metric tons per year.

By 2015, the company – which had started off as an unincorporated sole proprietorship 65 years prior – converted to a public limited company in preparation for its initial public offering on the Karachi Stock Exchange, raising just shy of Rs700 million.

Where the company stands today

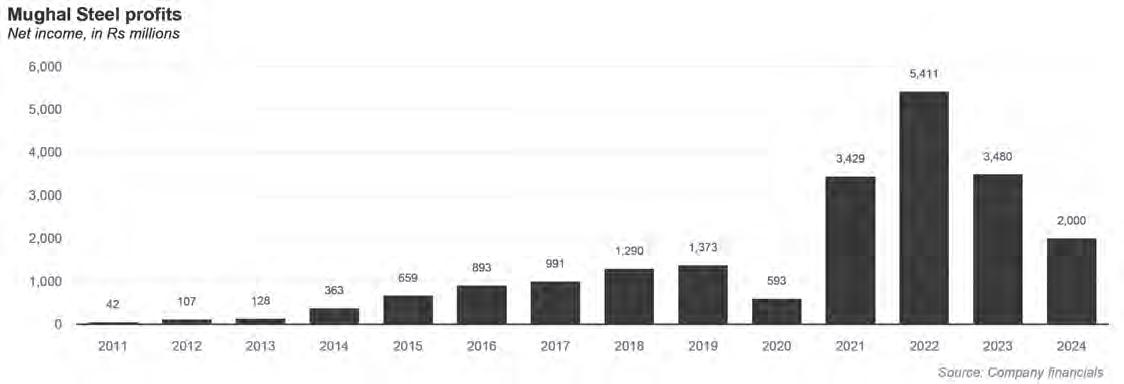

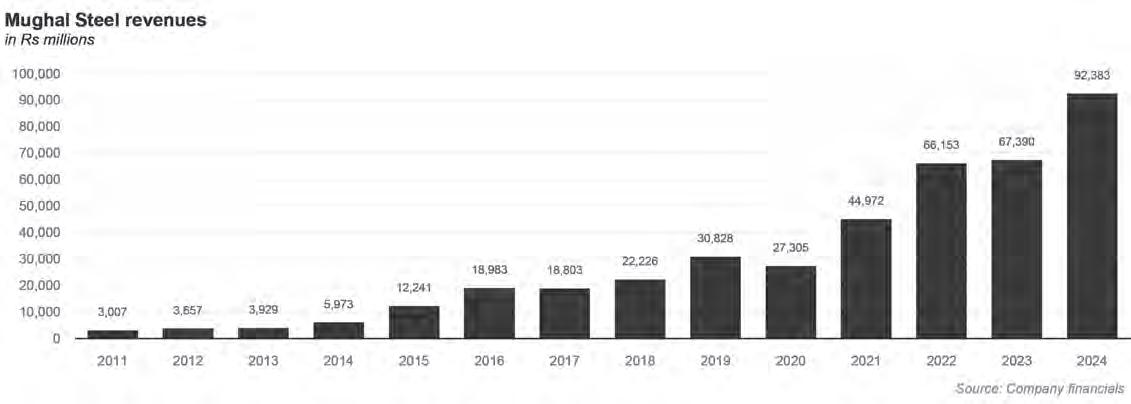

Mughal Steel has been one of the most dynamic companies in Pakistan’s steel sector and one of its fastest growing. In the 13 years that the company has been an incorporated business, it has grown its revenue from Rs3 billion in financial year 2011 to Rs92.4 billion in the financial year ending June 30, 2024, an average annualized growth rate of 30.1% per year. And despite several difficult years, it has never made a loss during any of those years.

This is a company that has been able to steadily grow its market share and, unlike most of its competitors in the steel industry, has exposure not just to industrial users of steel, but also supplies steel directly to consumers looking for steel girders for home construction.

And the company continues to expand its industrial footprint. Mughal Energy Ltd (MEL), a subsidiary of Mughal Steel, plans to setup a 55MW coal-fired power plant with the proposed investment of $137 million in Lahore, it announced in June of this year. The energy from that power plant would be used to supply all of the production units for the company, which currently operates the second largest steel manufacturing plant in the

And earlier this year, the company had also announced an investment plan that would involve the company investing in Balancing, Modernization and Replacement (BMR) of existing bar re-rolling mill and procurement of 6 gas-fired generators (3.1MW each) at a total estimated cost of Rs1.75b. The company management plans to enhance its re-bar capacity from the existing 150,000 tonnes to approximately 350,000 tonnes. The company expects that the efficiency of the bar re-rolling process will improve resulting in reduced manufacturing costs and improved margins.

All of these moves have come as demand challenges have continued to weigh on the industry and may even be driving a consolidation in the industry, though Mughal appears to be the one company bucking broader industry trends. According to IMS Research, the industry’s profitability during the second quarter of calendar year 2024 was driven largely by a robust quarter from Mughal Steel.

Part of what drove the higher revenue and profitability was the surge in global copper prices, which tends to have a downstream impact on other metal products such as iron and steel. As the steel sector navigates these ongoing challenges, the focus remains on companies like Mughal, which are leveraging diversification and strategic growth in non-ferrous segments to bolster their financial performance amid a tough operating environment.

Zooming out, the steel industry faces its own set of macroeconomic challenges. Steelmaking in Pakistan relies heavily on imported raw materials, with iron ore and scrap metal comprising 60-70% of production costs. Between 2018 and 2024, scrap metal prices doubled, only to fall back to earlier levels. Yet, the rupee’s sharp depreciation has eroded the cost advantage this drop should have provided. Steelmakers are now grappling with a dollar that trades at Rs 280—up from Rs 100 just a few years ago.

Why the regulatory wants to allow this transaction

One suspects the reason the SECP is allowing this to happen is simple: they know that Pakistanis tend to be control freaks and are loathe to give up control. As a regulator, the SECP has competing responsibilities. Yes, having companies with strong corporate governance and accountability is important. But so is increasing the liquidity and investment opportunities open to the general public through the capital markets.

As matter stand today, the total market capitalization of all companies listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange is under 14% of the total gross domestic product (GDP) of the country. This is significantly lower than even our regional peers. More worryingly, the market is not representative of the economy as a whole and many of Pakistan’s largest and most profitable businesses are not publicly listed.

While there are a great many reasons why each individual company might choose not to list publicly, the fact remains that fear of losing family control over what tend to be family-owned businesses is a major concern. The bargain the SECP is making is essentially hoping that more family businesses will be willing to share the economic value of their businesses if they do not have to give up meaningful control over their companies.

The Mughal Steel dual class shareholding, then is a trial balloon to see if some of the owners of Pakistan’s privately held companies take notice. In the next five years, if more of them decide to list their companies on the exchanges, this bet will have paid off.

Whether it will be worth the price – in the form of reduce accountability and potential for abuse of minority shareholder rights – remains to be seen. n

The landmark ruling could redefine the balance between consumer protection and industry viability, enabling drug manufacturers to sustain the supply of essential medicines amidst rising production costs

By Muazzam

“To state that the most expensive drug is one that is needed but not available would be a truism”

These were the words in which Justice Babar Sattar of the Islamabad High Court delivered a delicately scathing indictment of the federal government’s continued efforts to exert control over drug prices in Pakistan. The historic verdict of the IHC was delivered on the 30th of October as the result of a writ petition filed by Getz Pharma against the Federal Government.

But it was not Getz Pharma alone. Nearly the entire pharmaceutical industry in Pakistan including ICI Pakistan Ltd, GlaxoSmithKline Pakistan Ltd, SAMI Pharmaceuticals Pvt Ltd and Indus Pharma Pvt Ltd had filed their own petitions, and this decision provides them the same relief as Getz Pharma.

What was the core issue? The government, as we all know, has long been involved in regulating drug prices in Pakistan for populist appeal. But since drug manufacturing is a private business, if pharma companies cannot sell at viable prices they end up with supply shortages. Of course, there is an argument to be made for regulation. Life saving drugs should be accessible to everyone, and this is a business where small margins should be encouraged and competition should be fostered to make pricing more competitive.

But this particular case revolves around existing laws. You see, there is a Maximum Retail Price (MRP) policy in Pakistan that was enacted for drugs in 2018. This policy governs how drugs are priced, but also has safeguards that allow drug manufacturers room to increase their prices during times of hardship. It was this core issue that led the pharma industry to the courts, and the government’s own law was what the IHC used to rule against them.

Of course, the core issue here is multifaceted: A government aiming to protect consumers but failing to adhere to its own pricing policies; a pharmaceutical sector teetering on the edge due to profitability concerns; and a national healthcare system stretched thin, where accessible pricing of essential drugs remains uncertain.

This ruling, along with recent developments, probes whether the government can balance these competing interests without collapsing under the weight of the country’s economic challenges.

Pakistan’s drug pricing structure, designed to protect consumers, has increasingly ignored the economic realities faced by manufacturers who are left bearing the brunt of inflationary pressures without government mitigation. In early 2023, 70 pharmaceutical companies issued a plea to the Ministry of Health Services and DRAP, highlighting the immediate threat posed by fixed MRPs. These companies warned of possible industry collapse without price adjustments that reflect inflation and

ensure sustainable profitability, critical for addressing drug scarcity.

This landmark decision shines a stark light on Pakistan’s urgent need for an updated approach to MRP policy, one that ensures affordability for consumers while preserving the viability of manufacturers.

At its heart, it raises a critical question. As prices rise and government intervention lags, will essential medicines remain within reach for Pakistan’s vulnerable populations?

So how did we get to this point?

Amid the spiraling dollar-rupee inflation and global supply chain disruptions since 2020, Pakistan’s pharmaceutical industry has been facing unprecedented financial pressure. For Getz Pharma and many others, the rising cost of imports, as over 80% of the raw materials used in drug production are imported, has forced a steep increase in production expenses.

Many small manufacturers, lacking the financial cushion to absorb these costs, were compelled to shut down operations, as over 200 small manufacturing plants had to close due to untenable production costs. The impact was felt even more acutely as, despite these challenges, the government maintained its fixed MRP policy, prioritizing consumer access to affordable medicines over industry sustainability.

Against this backdrop, Getz Pharma sought an MRP increase under the “hardship” clause of the Drug Pricing Policy, 2018. Under this provision in early 2022, Getz applied for an MRP increase through the DRAP to ensure it could continue manufacturing at a time it is becoming unfeasible to produce.

Feisal Naqvi, legal counsel for Getz Pharma, explained, “the drug in question is a lifesaving drug used in hospitals to provide anesthesia to children, and another form of this drug was already being sold in the market for Rs19,000.”

The name of the Getz-manufactured drug for which a hardship MRP was requested and found that it was ‘Sevof’ whose price was set at Rs5,526 by DRAP in 2019. Despite its DRAP-approved MRP-increase to Rs 17,571, on account of economic hardship, which the government later rejected in 2022, an alternative called ‘Sevofluorane’ was already being sold at around Rs19,000.

In contrast, Naqvi explains that, “the hardship MRP requested by Getz, and approved by the Drug Pricing Committee, was much lower at roughly Rs17,000,” which would have offered a more affordable alternative in the market.

Yet, even as the economic situation continued to worsen, the government failed to respond within its mandated time, leaving Getz without recourse and unable to raise prices by the allowed 10% in the absence of a timely response. This delay underscored the growing discontent within the industry, as pharmaceutical companies bore the burden of

inflation alone while consumers faced potential shortages of critical medicines.

Although the government acknowledged these issues in May 2023, granting a onetime allowance for manufacturers to increase MRPs for essential drugs by up to 70% of CPI (capped at 14%) and non-essential drugs by CPI (capped at 20%), this move was viewed as too little, too late for an industry that had long voiced its grievances. The policy shift did provide some relief: pharmaceutical earnings rose by 70% to Rs13.3 billion in FY24, and sales increased by 19% YoY to Rs286 billion, with previously scarce medicines reappearing on shelves. Additionally, gross margins improved, better reflecting the industry’s increased costs.

In February 2024, the Ministry of National Health Services also responded by increasing MRP for 146 essential drugs and deregulating non-essential drug prices. This change allowed companies to adjust prices based on CPI inflation with specific caps, offering some relief to address supply challenges.

As a result, the start of the current fiscal year saw further gains with a 560% YoY growth to Rs5.6 billion in Q1FY25, attributed to a move that mirrors India’s approach to balancing free-market principles with price controls. This deregulation, however, only partially alleviates the financial strain facing the industry, as the MRP remains fixed for essential drugs.

Despite the government’s latest intervention, cost pressures remain high, with gross margins rising from 26% in FY23 to 30% in FY24, partly due to reduced raw material costs for some drugs. Meanwhile, selling and administrative expenses grew by 24% and 12% in line with inflation trends, and finance costs surged by 23% due to the increase in KIBOR rates from 18% to 22%

This brings us to the present legal challenge, where the recent judgment in favor of Getz Pharma calls for a critical examination of the MRP framework, its implications for industry stability, and the accessibility of essential medicines for consumers.

How does MRP and its legislation work?

MRP is a form of price-control inconsistent with the free-market system, but a much-needed form of government intervention in emerging economies like Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. This not only protects consumers and provides them access to medicines at prices affordable to them, but also protects the domestic industry as foreign players are prevented from dumping artificially lower price rates.

This system also pays little regard to retailers as they lose control over what profits

they make, which compounds the existence of a black market given that at times of shortage, smuggled and spurious drugs are sold at 3 to 4 times the prices.

In emerging economies like Pakistan, where there’s two categories of drugs in terms of pricing, ‘Essential Medicines’ and ‘All other drugs’, an MRP system has been used to shift the burden of increased inflation from the consumers to the producers, with minimal government intervention to build manufacturer capacity to fulfill what should be the government’s responsibility.

Prior to the government’s commitment earlier this year to deregulate non-essential medicines, there existed, and still exists until further amendments, 3 unique categories of MRP, under the Drug Pricing Policy.

Firstly, Annual Adjustments (Clause 7) provide a controlled yet predictable mechanism for price increases across most drugs. These adjustments are tied to inflation, allowing MRPs to rise annually based on a formula that factors in economic indicators like currency depreciation. This measure helps cover manufacturers’ rising costs in a manner that remains affordable for consumers.

Secondly, New Entrants (Clause 8) addresses the pricing of new drugs entering the market. Here, DRAP sets MRPs by benchmarking prices in countries like India and Bangladesh, with the goal of encouraging innovation and fair competition while keeping prices aligned with regional standards.

Lastly and most importantly, Hardship Cases (Clause 9) offer an urgent response mechanism for price adjustments due to exceptional economic challenges, such as rapid currency depreciation or import cost spikes. This clause is essential for safeguarding the supply of critical drugs, allowing manufacturers to apply for MRP increases when production costs soar unexpectedly.

As per the governments own policies that led to the creation of DRAP, under the DRAP act 2012, and the Drug Act, 1976, the government has delegated this responsibility of determining prices to the Drug Pricing Committee, and therefore according to Naqvi and Justice Babar Sattar, bound by it in absence of a reasonable justification to reject it.

Did the Government act reasonably and responsibly amid Getz’s economic hardship?

In the recent judgment, Justice Babar Sattar criticized the federal government’s refusal to accept hardship MRP adjustments for Getz Pharma, emphasizing that this

decision reflected a failure to follow its own established policies. This rejection, which came without adequate explanation or adherence to the Drug Pricing Policy’s provisions, cast serious doubts on the government’s commitment to ensuring both consumer affordability and accessibility to essential drugs.

According to Naqvi, “it’s simple. If the government has a policy, it must follow it. If it doesn’t wish to follow it, then it should change its policy. But in this case, the policy that safeguards my client still exists.”

This pointed remark underscores the core of the issue. The government has failed to act in accordance with Clause 9 of the Drug Pricing Policy, which explicitly outlines the procedure for hardship MRPs. By ignoring both the policy framework and the Drug Pricing Committee’s (DPC) recommendations, the government effectively undermined the principles of fair governance.

Justice Sattar observed that the government’s decision appeared arbitrary and unreasonable, lacking in both transparency and accountability. He noted that the Drug Pricing Committee, composed of industry experts, had recommended an adjusted MRP of Rs17,000 for Getz Pharma’s drug, a price notably lower than the Rs19,000 charged by a competing manufacturer.

This recommended adjustment would have not only provided a more affordable alternative but also ensured the continued availability of the drug. In rejecting this without valid reasons, the government failed to balance consumer affordability with accessibility, a critical responsibility in healthcare policy.

Furthermore, Justice Sattar pointed out that by acting inconsistently with its declared guidelines, the government destabilizes the pharmaceutical sector, creating uncertainty for manufacturers and threatening the supply of essential medications to the public.

In a healthcare landscape where access to lifesaving drugs is paramount, this judgment underscores the necessity for the government to act responsibly, transparently, and in alignment with established policy. The arbitrary handling of Getz Pharma’s hardship request highlights the risk of bureaucratic inertia overriding the core purpose of policies meant to safeguard both consumer welfare and industry viability.

How does regulation impact the economy?

The complex web of regulations governing drug prices in Pakistan has far-reaching economic implications, affecting various stakeholders. Lets look at its impact on each stakeholder, including the government itself, to better understand the challenges and economic distortions creat-

ed by inconsistent and stringent price controls:

(i) Producers: rising costs without mitigations

Pharmaceutical manufacturers in Pakistan face an uphill battle to sustain operations amidst mounting production costs and volatile exchange rates. With 80% of raw materials imported, currency devaluation significantly raises costs, particularly for multinationals who already operate on thinner margins due to regulatory price caps. The government’s refusal to adjust MRPs in line with inflationary pressures and currency fluctuations leaves manufacturers with few options.

As a result, multinational companies are gradually exiting the market, as seen in previous financial disclosures, prior to the notification surrounding deregulation of non-essential medicines, where three publicly listed pharmaceutical companies reported losses of Rs600 million, Rs500 million, and Rs300 million, respectively. This exodus not only diminishes competition but also disrupts the supply of essential drugs, putting further strain on the healthcare sector.

(ii) Retailers: diminished profits, increasing risk

For retailers, the regulated MRP limits profit margins, making it financially unrewarding to stock and sell certain drugs. In a low-margin environment, pharmacies and medical stores find little incentive to prioritize medicines with stringent price caps. This situation is exacerbated during times of shortage when demand is high, yet legal channels of profit are constrained.

Consequently, the rigid pricing policies inadvertently encourage a black market, where unofficial channels sell these scarce drugs at unaffordable rates, undermining regulated prices. Retailers, thus, operate in an environment where potential profits are not only constrained by regulation but also siphoned off by illicit traders, leading to a fragmented and inefficient supply chain.

(iii) Consumers: limited access and the rise of the black market

The intended purpose of price controls is to make medicines affordable for consumers. However, the current regulatory structure often has the opposite effect, limiting the availability of essential drugs and pushing desperate consumers toward black-market alternatives.

In times of scarcity, medicines regulated by strict MRPs are often unavailable in legal retail stores but can be found on the black market at inflated prices, sometimes three to four times the controlled MRP. For low-income consumers, this creates a heartbreaking dilemma: pay exorbitant black-market rates or forgo potentially lifesaving medication.

The regulations intended to protect

consumers from price gouging have thus inadvertently made medicines both unaffordable and inaccessible, undermining the very goal of consumer protection.

(iv) Government: Economic Leakage and Burdened Imports

The government’s stance on maintaining low drug prices aims to safeguard consumer interests, but it simultaneously creates an unintended economic burden. By discouraging local production through stringent price caps, the government increases dependency on imported medicines, which in turn puts additional pressure on foreign reserves.

The regulatory environment has created a reliance on imports not only for raw materials but, increasingly, for finished drugs as well. As local producers find it financially unsustainable to operate, import bills rise, exacerbating the balance of payments issue. Moreover, the lack of policy flexibility means the government must deal with increasing black-market activity and the resultant loss in tax revenue, further straining public finances.

In sum, the rigid MRP regulation, while well-intentioned, triggers a cascade of economic consequences. Without adapting the regulatory framework to address these market realities, Pakistan risks deepening the healthcare crisis, driving manufacturers away, increasing the black market’s influence, and overburdening its already fragile economy.

The Public Health Paradox: do price controls limit access?

While MRP controls are meant to keep essential medicines affordable, they often result in unintended shortages, leaving patients without critical drugs. The reliance on imports means that fluctuations in foreign exchange and rising customs duties significantly impact production costs. With MRPs fixed by the government, manufacturers face constraints in adjusting prices to reflect these higher costs, leading some companies to cut back or withdraw products altogether.

For patients with chronic illnesses, the implications are severe. Limited production and market exits have led to recent shortages, pushing many consumers towards black markets or without any medication. In a country where healthcare spending is less than 3% of GDP, these price controls are squeezing both access and affordability, creating a cycle of artificial scarcity.

Other emerging economies have adopted flexible pricing for non-essential drugs, focusing controls solely on essential medicines. Adopting a similar approach could allow Pakistan to protect public health without stifling

the market, ensuring that lifesaving medicines remain accessible even in times of economic instability.

The recent developments

The recent price adjustments for essential drugs and the deregulation of non-essential medicines could mark a turning point for Pakistan’s pharmaceutical sector. As the government has recently signaled deregulation, approving higher MRPs for 146 essential drugs, while giving companies the freedom to price non-essential drugs, it promises to boost profitability, with gross margins rising from 26% in FY23 to 30% in FY24, and a further surge anticipated as interest rates decline.

However, the broader question remains whether these steps indicate a genuine shift in government policy or are simply temporary measures. Industry experts have previously emphasized Pakistan’s lack of domestic biotechnology infrastructure, contrasting sharply with India’s 300 and China’s 3,000 biotechnology plants. The absence of R&D facilities and API (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient) production not only limits the industry’s growth but also keeps it reliant on expensive imported raw materials.

Dr. Khurran Hussain from Getz Pharma previously proposed that the government tap into the Central Research Fund, worth five billion rupees, to develop local R&D facilities and promote public-private partnerships. Such measures could pave the way for innovation and reduce import dependency. This would mirror the buffer-stock protections seen in the agricultural sector, where Minimum Support Prices (MSPs) safeguard farmers from market fluctuations.

As healthcare spending in Pakistan hovers below 3% of GDP, the IHC’s recent judgment underscores the urgent need for a balanced approach in drug pricing policy. This decision compels the government to rethink how it supports both consumer access and industry viability, key pillars that are currently misaligned. While recent measures like MRP adjustments and deregulation of non-essential drugs offer hope, they may only scratch the surface of deeper systemic issues in Pakistan’s pharmaceutical sector.

Will these reforms foster a competitive, innovation-driven industry, or are they simply short-term remedies? The true test lies in the government’s commitment to honoring the IHC’s ruling by establishing clear, actionable support for producers facing economic hardships. A genuine shift in policy could ensure a resilient supply chain for essential medicines, safeguarding the health of hundreds of millions while reinforcing the industry’s foundation. n