IN Sunset Park

This research project revisits the cooperative legacy of Brooklyn’s Sunset Park, a workingclass neighborhood shaped by global and local economic forces, as well as successive waves of immigrants who have settled, built roots, and thrive together. Over the past century, the neighborhood has seen periods of prosperity, urban decline, revitalization and, most recently, gentrification. The collective strength of Sunset Park’s diverse immigrant communities has been essential in overcoming hardships and making meaningful contributions to the neighborhood's development and economy.

Delving into Sunset Park’s cooperativism, this research aims to identify strategies, opportunities and challenges for expanding shared ownership models in the context of the Community Land Act. This set of bills, if passed, would assist housing cooperatives, mutual housing associations, community land trusts, and other nonprofit organizations to develop, expand, and preserve permanent affordable housing, along with accessible community, commercial, and other spaces of critical need.

Sunset Park's rich history of cooperative housing, providing affordable housing, spans three distinct periods. The first began in 1916, when the Finnish community established the first self-managed worker housing cooperative in the United States. This groundbreaking initiative led to the creation of more than 25 Finnish co-ops throughout the neighborhood. While many of these co-ops remain collectively managed, some have transitioned to marketrate cooperatives, reflecting the broader demographic shifts and transformations that have shaped Sunset Park over the years.

The second period unfolded half a century later, during the late 1970s and early 1980s, amid the city’s near bankruptcy. During this challenging time, when housing abandonment ravaged many working-class neighborhoods in Brooklyn, the Sunset Park community rallied to transform old, vacant, and derelict properties into housing cooperatives. With hundreds of recently foreclosed buildings in the city’s possession in Brooklyn and across the city, New Yorkers pushed local authorities to establish public programs that would sponsor the rehabilitation of these properties.

Tenant-led initiatives deeply rooted in the squatter movement—such as Urban Homesteading, Sweat Equity, Community Management, and the Tenant Interim Lease Program—gave new life to entire multifamily buildings, converting them into low-income housing cooperatives. These co-ops were legally reconstituted as Housing Development Fund Corporations (HDFCs), specifically designed to serve low-income individuals and families. Today, most of these HDFCs are still managed by the original shareholders, although some have been converted into affordable rentals. New HDFCs have also been established in the area to serve specific populations, carrying forward Sunset Park’s legacy of collective, community-driven housing solutions.

Although housing cooperatives have provided significant benefits to residents and communities for over 100 years in both the district and the city, there is not enough information about their impact at district and city levels. For decades, the social and economic importance of this housing model was overlooked by politicians, city officials, and policymakers, leading to the dissolution of many programs that once supported and preserved housing co-ops. During this period, the development of rental housing barely affordable and market rate housing was heavily promoted by non and for profit development corporations, respectively. This trend largely overshadowed shared ownership approaches to housing that prioritize community control and shared management.

Not only the lack of support for housing cooperative development is concerning, but also the fact that housing cooperatives are increasingly at risk, especially in neighborhoods like Sunset Park, where speculation and gentrification are soaring property values. In this context, small housing cooperatives targeted by investors looking for profit are at risk. One of the few strategies proven effective in preserving deeply affordable housing in perpetuity is the establishment of community land trusts (CLTs).

CLTs ensure that the land on which cooperatives and low-income rental housing are built is stewarded in perpetuity, safeguarding it for the benefit of the entire community. Over the last decade or so, some community groups have looked into this model across the city to preserve low-income and immigrant communities, including Sunset Park. This project aims to delve particularly into the strategies needed to bring together the community and campaign for the establishment of a CLT. It seeks to find paths to achieve a collective vision, and identify opportunities and challenges to be considered.

DEVELOPED BY

Delaney Connor

Shivani Dave

Arooj Fatima

Zola Harper

Molly Meng

Gant Roberson

Antonia Simo

Ruth Wondemu

COORDINATED BY

Gabriela Rendón

Associate Professor of Urban Planning and Community Development

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

NEIGHBORS HELPING NEIGHBORS

Aura Mejia

Fabian Bravo

Carlos Villon

Jared Watson

SUNSET PARK IS NOT FOR SALE ORAL HISTORY PROJECT

Kelly Anderson

Rodrigo Camarena

Fabian Bravo

Jeremy Kaplan

Aura Mejia

Marcela Mitaynes

Carlons Villon

Jared Watson

Elizabeth Yeampierre

Neighborhood Demographics

• Sunset Park, Brooklyn

• A multilingual community

• Changes in race over time

• Median household income

• Median rent

Changes in the neighborhood

• Sunset Park Housing: Past, Presentand Future

• Rezonings

• Future threats to Sunset Park: The City of Yes and its impacts

• Organizations and their roles in Sunset Park

Revisiting shared ownership in Sunset Park

• Co-operative movements and housing solutions

• Co-operatives movements around the globe

• The co-operative movement in New York City

• Social housing and their types

• Community Land Trusts

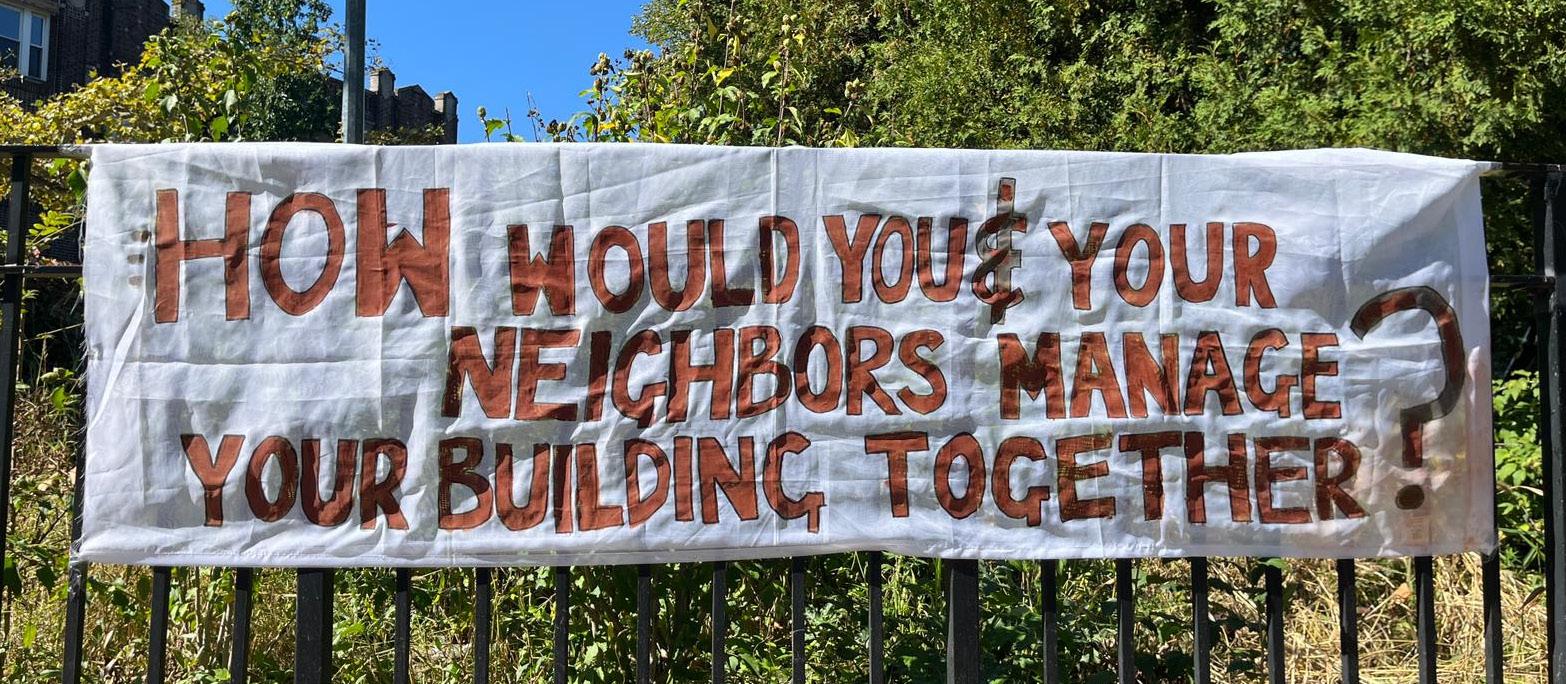

What does Sunset Park think about co-operatives?

• Introducting CLTs in Sunset Park

• Resident Survey

• Public Faculty

• An opportunity for community and trusts

Sunset Park is a culturally diverse area surrounded by Greenwood Cemetery (north), Borough Park (east), Bay Ridge (south), upper New York Bay (west). Historically, it has been home to a variety of immigrant communities that are under threat of gentrification today. It is a part of Brooklyn Community District 7 (CD7), that contains almost 200 acres of the South Brooklyn waterfront .

After the construction of the 3rd Avenue elevated railroad extension in 1983 and the opening of the subway along 4th avenue in 1915, development of row houses and industrial centres in the area took place.

It has been home to Irish, Italian and Scandinavian immigrants in the early 20th century and saw an influx of people from Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic and a few other Latin American countries in the second half of the 20th century.

A large increase of immigrants from China was seen in 1980s, and the 1990s saw an influx of people from Mexico, the Middle East and some from rural China. According to the American Community Survey’s estimate, CD7’s population was 124,433 in 2022.

With an estimated 40.4% of the residents across Sunset Park community district born outside of the United States, among those some of the more immigrant-dense tracts reaching nearly 70%, Sunset Park at its spirits has a multilingual core. According to American Community Survey (ACS) data 2018-2022, 49,324 estimated residents speak English less than “very well,” with 54.9% primarily speaking Spanish and 38.9% preferring Chinese.

Spanish

Chinese (incl. Mandarin, Cantonese)

English Only

Historically, Sunset Park has been a predominantly working-class neighborhood with large Hispanic and Asian populations, particularly Puerto Rican, Mexican, and Chinese communities. However, recent data indicates that while the Asian population, especially the Chinese community, has remained relatively stable or even grown slightly, the Hispanic population has been steadily decreasing. This trend reflects broader patterns of displacement, as rising rents push long-time Hispanic residents out of the neighborhood.

At the same time, the White non-Hispanic population has been gradually increasing, likely due to an influx of new residents moving into the neighborhood as part of broader gentrification trends in Brooklyn. These demographic shifts have altered the social and cultural landscape of Sunset Park, leading to increased tensions around affordability, access to housing, and the preservation of local culture.

Hispanic

Asian Non-Hispanic

White Non-Hispanic

The largest share of households in Sunset Park have a median household income between $60,000 and $100,000; however, in 2022, Sunset Park also had a poverty rate of 20.7% (which is higher than the city-wide rate of 18.3% for that year). This dichotomy has manifested in the area through changing

$76,000 to $85,999

$60,000 to $75,999 more than $86,000

$46,000 to $59,999

$30,000 to $45,999

housing trends (i.e. gentrification and commercialization of certain areas), changing business trends (from locally-owned to big name stores) and even changing communities, as the locals are being priced out due to the factors listed previously.

$1000-$1499

$1500-$1999

$2000-$2499

$2500-$2999

A combination of housing and infrastructure changes has meant a significant median rent difference in Sunset Park. With a 36.6% increase in median gross rent between 2006 and 2022, the residents of Sunset Park are facing a housing crisis.There is a loss of both market-rate and affordable housing, and

gentrification of some areas has ensured that the housing units that were affordable are now priced too high - making it so that the community itself cannot afford to live there and thus, may get displaced.

Balancing Development, Affordability, and Community Identity:

Sunset Park, a vibrant and diverse neighborhood in Brooklyn, has faced increasing development pressure over the past two decades. With its proximity to the waterfront and industrial areas, it has become a prime target for rezoning and redevelopment. While new projects have brought change, they’ve also driven up housing costs, displacing longtime residents and raising concerns about preserving affordability and cultural identity.

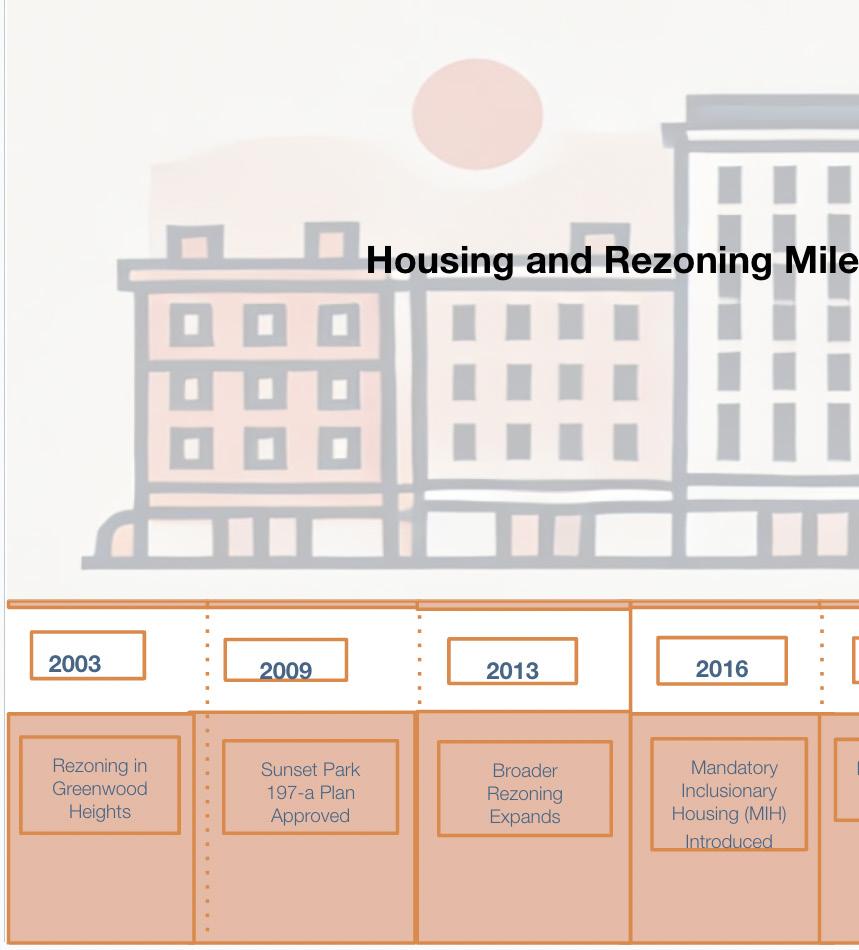

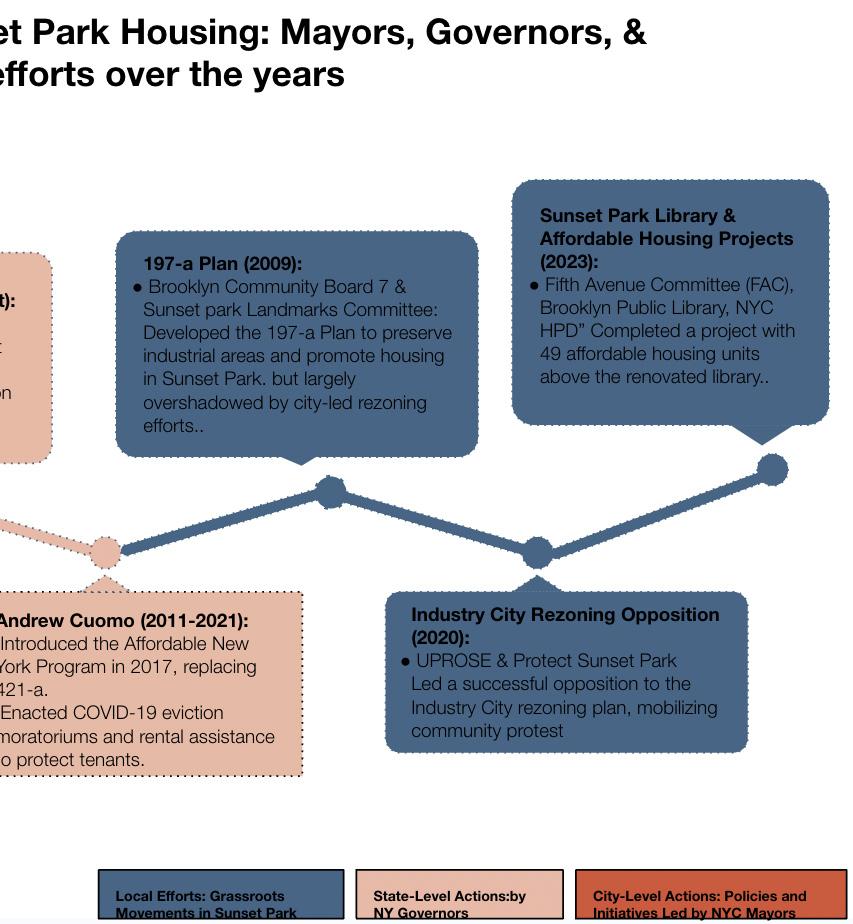

From the Sunset Park 197-a Plan to Broader Rezoning Efforts:

Zoning decisions in New York City have significantly shaped neighborhoods like Sunset Park. The 1916 Zoning Resolution, introduced under Mayor John Purroy Mitchel, aimed to improve housing conditions by promoting better ventilation, lighting, and sanitation. However, it was the 1961 Zoning Resolution, under Mayor Robert F. Wagner, that had a profound impact on Sunset Park. This resolution divided the neighborhood into distinct industrial and residential zones. While it helped preserve Sunset Park’s industrial base, it also restricted residential growth, limiting affordable housing opportunities.

In the early 2000s, under Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration, broader rezoning efforts were introduced to accommodate New York City’s growing population. In 2003, Greenwood Heights (northern Sunset Park) was rezoned to allow for higher-density housing. This rezoning aimed to encourage residential development in areas previously designated for industrial use, particularly near the waterfront.

By 2009, further rezoning along major corridors like Fourth Avenue expanded housing

opportunities as part of the city’s broader strategy for economic development. However, these changes, while promoting growth, also contributed to rising property values, increased rents, and the displacement of long-term residents.

Despite the approval of the Sunset Park 197a Plan in 2009—a community-led initiative developed to preserve the neighborhood’s industrial identity and ensure affordable housing—the broader city-led rezoning initiatives that followed often favored developers and market-rate housing. While the 197-a Plan was a positive step towards protecting the community’s interests, rezoning efforts under Mayor Bloomberg in the early 2010s introduced higher-density, market-rate housing across New York City, including in Sunset Park.

These changes, though intended to stimulate economic growth, led to rising rents and gentrification, which undermined the long-term affordability of the neighborhood. Later, Mayor de Blasio’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) program in 2016 required developers to include affordable housing units in new developments, but it still struggled to meet the growing demand, leaving many residents unable to afford homes in the area. In 2017, Mayor de Blasio expanded his housing efforts with Housing New York 2.0, a plan aimed at creating and preserving 300,000 affordable homes by 2026. While this plan focused on increasing affordable housing availability, it faced concerns about gentrification and displacement, as communities worried that new development would drive up rents and push out long-time residents.

Community Resistance, Pandemic Impact, and the Fight for Affordability:

Sunset Park’s waterfront, once dominated by industry, has increasingly become a focus of redevelopment. One key initiative was the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway, proposed in 2004 by community groups and supported by

the NYC Department of Parks & Recreation, aiming to create bike paths and parks along the waterfront. While widely supported, concerns arose about gentrification, as improvements made the waterfront more appealing to developers, contributing to rising property values and rents.

A significant flashpoint came in 2020 with the proposed Industry City rezoning, a redevelopment plan pushed by private developers and supported by Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration. Aligned with the city’s 2015 Industrial Action Plan, which aimed to revitalize industrial zones, the proposal sought to transform the complex into a mixed-use development. Local organizations, including UPROSE and Protect Sunset Park, along with former City Council member Carlos Menchaca, opposed the plan, citing concerns over displacement. After intense community resistance, the rezoning proposal was withdrawn in 2020, marking a victory for the community.

As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded in 2020, housing challenges worsened across New York, including in Sunset Park. In response, emergency measures such as an eviction moratorium and rental assistance programs were implemented to prevent mass evictions. Advocacy groups, including Housing Justice for All, pushed for stronger tenant protections statewide, leading to the introduction of the Good Cause Eviction Bill, which was championed by State Senator Julia Salazar and Assemblymember Pamela Hunter. The bill was passed by the New York State Legislature and went into effect on April 20, 2024. It limits evictions to valid reasons and caps unreasonable rent increases based on inflation, offering crucial protections for market-rate tenants throughout New York State.

New Housing Models and the Challenge of Displacement:

The fight for affordable housing continues as Sunset Park grapples with new development pressures. In 2023, a partnership between the Fifth Avenue Committee (FAC), Brooklyn Public Library, and the NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) completed a project creating 49 affordable housing units above a renovated library. This model integrates public services with housing solutions, addressing both affordability and community needs, though replicating it across the neighborhood remains a challenge. Sunset Park has also been impacted by broader citywide initiatives, including Mayor Eric Adams’ City of Yes Plan, passed in 2024. The plan aims to streamline zoning regulations and increase housing production across New York City. However, much of this new development is focused on market-rate housing, which has exacerbated displacement in the neighborhood. Ensuring long-term affordability remains a critical challenge as displacement continues to affect long-term residents.

The Future of Sunset Park: Balancing Growth and Identity:

Sunset Park’s housing challenges underscore the tension between redevelopment and the preservation of its cultural and economic diversity. While city-led initiatives have attracted investment, they have also driven up housing costs and displaced long-term residents. As the neighborhood evolves, the central question remains: How can Sunset Park encourage redevelopment while maintaining affordability and protecting its unique identity? The ongoing push for stronger tenant protections, affordable housing, and community-led planning reflects a broader struggle over the neighborhood’s future—one where redevelopment and preservation must align to ensure residents can continue to call it home.

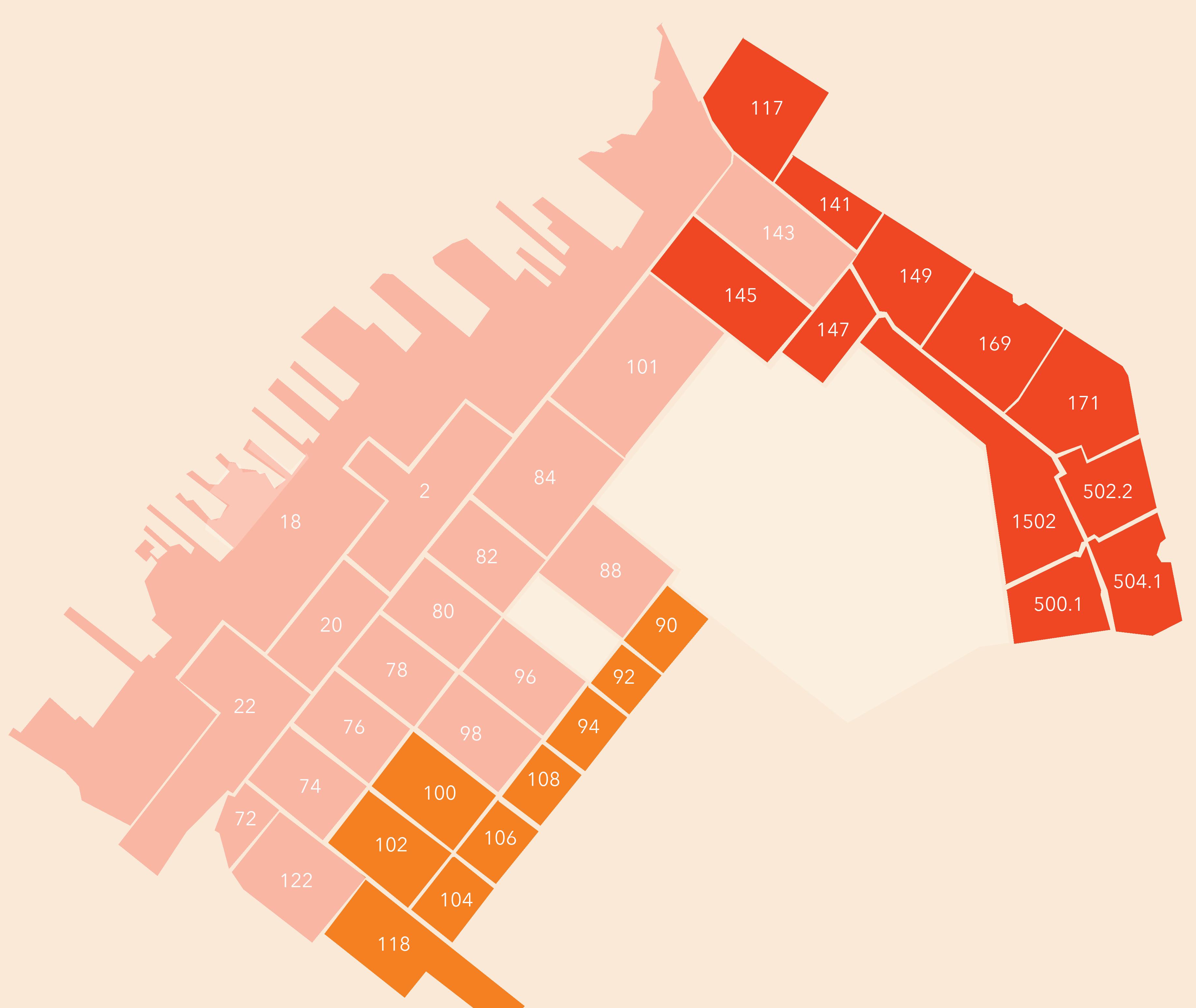

Upzoning

Downzoning

Unchanged

Zoning- regulates the use of land, applying it to new developments, add-ons and new uses of buildings/properties

R districts - this district only allows for residences and community facilities. The numbers signify density, R1 having the lowest density and R10 having the highest. Additional numbers signify additional controls.

C districts- commercial, as in retail, service or office use. Residential uses are permitted in all commercial districts with the exception of C7 and C8.

C1 and C2 are small retail services and shops.

C3 is for waterfront recreation.

C4 is for larger stores for goods and services.

C5 and C6 are business districts.

C7 is for amusement parks.

C8 is for heavy repair shops and automobile uses.

M districts- industrial/manufacturing, most commercial uses and some community facility uses. Residential development withhin an M district is only allowed within specific areas of the district with authorization. Light and medium M1 and M2 districts are governed by higher performance standards than heavy M districts.

M1 districts will have things like woodworking shops, repair shops, and wholesale service, storage facilities. offices, hotels and retail.

M2 districts have higher levels of noise, smoke and vibration are allowed, and some industrial activitity.

M3 districts are for things that generate lots of noise, traffic or pollution, like power plants, solid waste transfer facilities, recycling plants, and fuel supply depots.

Upzoning- Allowing for more dense construction within an area, increasing Flooring Area Ratios or relaxing zoning requirements. This is done to create more density and housing opportunity. While some argue that this could bring about more supply side opportunities for housing, tenant advocates argue that upzoning brings gentrification to neighborhoods by increasing housing costs. Upzoning tends to happen in neighborhoods with fewer white or wealthy residents and homeowners.

Downzoning- Downzoning means adding more restrictions to construction or shrinking the building envelope. Downzoning is often done in historic neighborhoods to preserve them. Downzoning typically happens in wealthier, whiter neighborhoods

Contextual Zoning- Regulates the height, bulk and setback from the street. This creates a more cohesive neighborhood.

Floor Area Ratio (FAR)- The ratio of the total building floor area to the area of the zoning lot. One can calculate the permited total building floor area by multiplying the FAR number of the district by the area of the zoning lot.

What’s happening right now with ongoing rezoning initiatives. The City of Yes is an active rezoning plan created under mayor Eric Adams aimed at streamlining development and promoting housing growth. City of Yes has faced criticism for allowing developers to bypass thorough community input and public review, raising concerns about transparency and accountability.

Goal of 500,000 homes over the next decade

Conversions of office buildings to houses

Accessory dwelling units- converting sheds, garages and basements into homes

Opening up restrictions on zoning

Building housing near public transit

Eliminating parking mandates for new homes

Allowing for the construction of smaller apartments

Mixed use zoning/ housing on top of businesses

20% square foot bonus if the bonus area is used for affordable housing

The borough presidents and community board 7, the community board of Sunset Park, support the City of Yes, with some caveats. However, more than half of the community boards have voted unfavorably. The Queens community board 7 says that the proposal will “destroy the quality of life in our neighborhood”, specifically in reference to the transit oriented development, accessory dwelling units and end to parking requirements.

Residents complain that an increased density will put more strain on the aging infrastructure, and that improvements will need to be made if more people are to live there. Basements are flooding due to undersized sewer infrastructure that cannot meet current demand. (Resident, Moore)

Tall buildings will mess with installed solar panels (also a part of the city of yes). Residents do not want buildings blocking the iconic view from Sunset Park.

(Community Board 7, Pena III)

Good for the environment but bad for public school teachers and MTA bus drivers who are more reliant on cars due to a lack of infrastructure for public transportation from the housing they can afford. (Resident, Moore)

More variable sized affordable housing, from studios to 3bed so it’s affordable for famlies too.

Unit size is capped so it’s not just bigger units being built but MORE units being built.

((Community Board 7, Pena III)

Town center zoning (housing above businesses on commercial streets) needing to also make some of this housing affordable, so it does not price out those around them.

(Community Board 7, Pena III)

Universal Affordability Preference (UAP) average Area Median Income (AMI) is reduced from 60% to 30%. This means that affordable housing would be affordable for someone with an income of $32,610 (30% AMI) as opposed to being affordable to someone with an income of $65,220 (60% AMI) (Community Board 7, Pena III)

City of Yes would allow developers to bypass the public review process ULURP (Uniform Land Use Review Procedure). The ULURP gives the community board 60 days to review the proposal and they must hold a public hearing for the proposal. While the proposal will continue on to

the borough president’s office, the city planning council and the mayor no matter what the community board says, those 60 days allow for the community to gather momentum and put up a fight againt proposals that are unpopular with the community.

Developers send in a proposal to the city council, borough president and communitiy boards impacted by the proposal.

The proposal gets certified when all forms are submitted. The countdown starts after certification.

The community board gets 60 days to review the proposal and they must hold a public hearing for the proposal. They then give their advisory recommendation to City Planning.

The City Planning Commission must hold a town hall within 60 days and give their approval, disapproval or any amendments to the proposal. Disapproval will go under council review.

The City Council does not always review when the City Planning Commission approves a plan, but is required to in certain situations like zoning map changes or housing and urban renewal plans. The City Council has 50 days to give their decision.

Mayoral approval is not required, but they can veto if they act within five days of the City Council’s decision.

The Community Land Act is a series of bills with the goal of creating permanant affordable housing.

COPA - the Community Opportunity to Purchase Act gives CLTs (Community Land Trust) and nonprofits priority to purchase multifamily buildings over developers when landlords decide to sell. COPA has already been put into place in Washington D.C. and San Francisco (how many have happened there how is it going over there)

TOPA - Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act gives tenants the priority to collectively buy their buildings. Tenants can collectively afford this through public loans or loans from nonprofits. Tenants can then pay off the loans like rent. TOPA is still in the early stages of being put into action in NYC (currently at the committee assembly stage), but TOPA has been enacted as early as 1980 in Washington D.C.. From 2003 to 2013 there were 1,400 units of affordable housing created.

Public Land for Public Good - City owned land often goes to for-profit developers. This bill would give priority to CLTs and nonprofit developers to increase the amount of permanently affordable housing.

Abolish and Replace the NYC Lien Sale - The Tax Lien Sale is when the city sends unpaid debt of the building owner (taxes, repairs, utilities, etc.) to a private trust which will then make money off of the debt by charging high interest. This translates in to homeowners going into debt, selling the buildings for less than they are worth or cutting costs on important repairs to tenant housing. None of this is an improvement to the community.

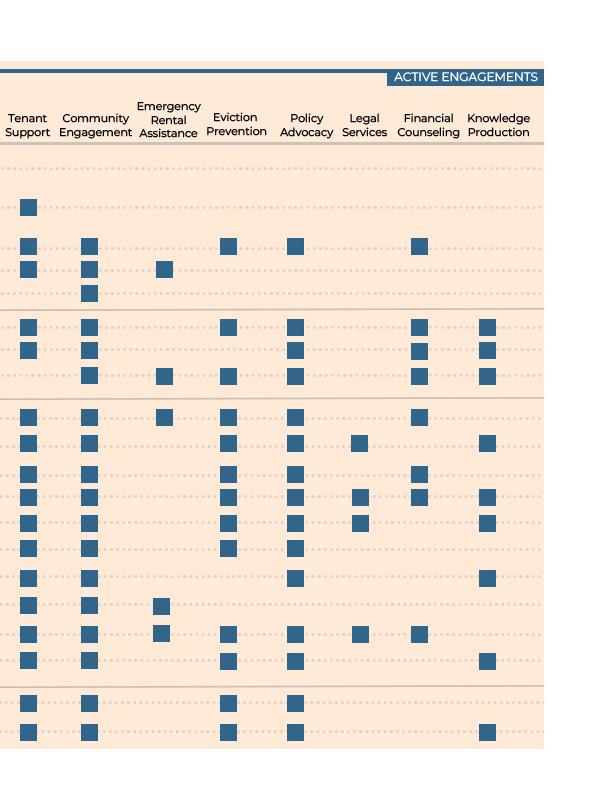

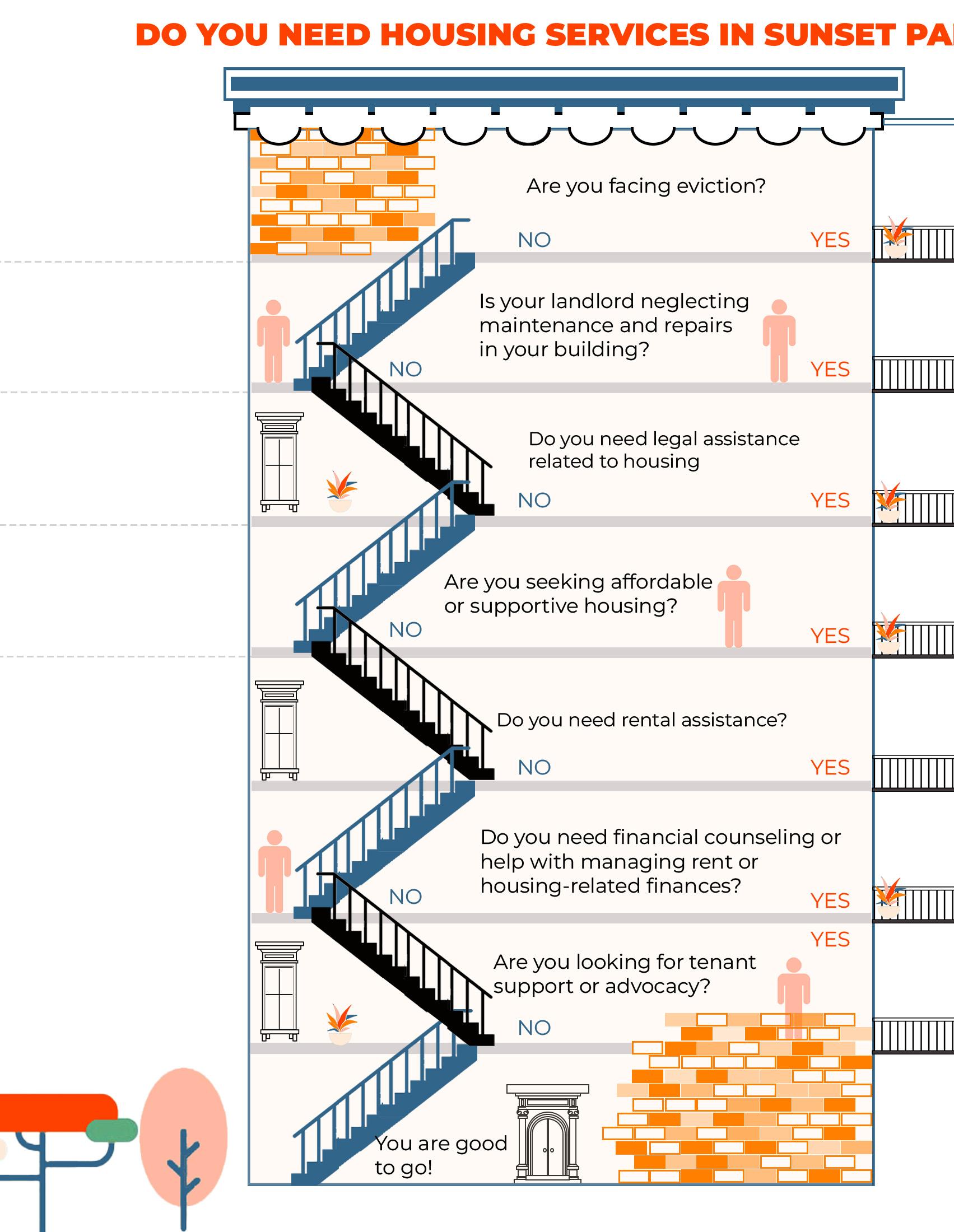

There are many nonprofit organizations across New York City working in different communities, serving a variety of purposes. However, several of these organizations share a common goal: providing essential housing services to support local communities. In Sunset Park, a number of organizations are present with this very focus. Each of them offers a range of services, from eviction prevention and affordable housing development to tenant advocacy and legal assistance. Some organizations help by creating housing co-operatives, while others focus on financial counseling, community engagement, and legal representation for housing disputes.

Among the organizations serving Sunset Park, some are based within the neighborhood itself, while others operate from nearby areas, offering services that extend into the community. In the following section, you will find detailed information on where these organizations are located, the specific services they provide, and guidance on which organization to approach depending on your housing needs. These nonprofits play a critical role in maintaining housing stability and affordability, especially as the area faces increasing pressure from gentrification and development. Their work ensures that vulnerable residents have the resources and support

Housing in Sunset Park is provided, managed, and advocated for by various kinds of organizations ranging from public agencies, nonprofit housing corporations, non-profit community organizations, and grassroots activism groups. As such, these housing initiatives vary in their focus, and in the kinds of housing and services they provide. Below is a list of the various organizations that are involved in housing in Sunset Park communities, and an infographic detailing the various forms of engagements that they are involved in.

Federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD):

The agency oversees a wide range of housing programs and initiatives, including public housing, rental assistance, affordable housing development, fair housing enforcement, and homelessness prevention. HUD provides funding to state and local governments, nonprofit organizations, and private developers to support the construction and rehabilitation of affordable housing, as well as rental assistance programs to help low-income individuals and families afford safe and decent housing. Additionally, HUD enforces fair housing laws to prevent discrimination in housing and promotes sustainable and equitable development practices to revitalize communities and improve access to opportunities for all.

Website: https://www.hud.gov/

The New York State Division of Homes and Community Renewal (HCR):

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) is a federal agency responsible for addressing housing needs and promoting community development across the United States. HUD’s mission is to create strong, sustainable, inclusive communities and quality affordable homes for all.

The New York State Division of Homes and Community Renewal (HCR) is tasked with advancing housing affordability, community development, and economic growth across the state of New York. HCR oversees various programs and initiatives aimed at addressing housing needs, promoting fair housing practices, and revitalizing communities. The agency administers programs to increase the availability of affordable housing, including financing for the construction and rehabilitation of affordable housing units, rental assistance programs, and initiatives to promote homeownership for low- and moderate-income households.

HCR also provides funding and technical assistance to support community development projects, infrastructure improvements, and economic development initiatives aimed at creating jobs and strengthening local economies. Additionally, HCR enforces fair housing laws to prevent discrimination in housing and promotes sustainable and inclusive development practices to foster vibrant, resilient communities across New York State.

Website: https://hcr.ny.gov/

The New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA):

The New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) is the largest public housing authority in North America, providing affordable housing to over 400,000 low- and moderate-income New Yorkers. Established in 1934, NYCHA manages public housing developments across all five boroughs, offering a range of housing services to low-income families, seniors, and individuals with disabilities. NYCHA’s mission is to provide safe, affordable housing and promote self-sufficiency for its residents through various programs, including job training, financial counseling, and health services.

In Sunset Park, NYCHA operates public housing developments that serve thousands of residents. Their housing services include maintenance and repair, tenant support, and community engagement programs aimed at improving

the quality of life for residents. NYCHA also plays a role in eviction prevention by providing financial counseling and connecting residents to resources for rent assistance. Additionally, NYCHA works to preserve affordable housing in the face of increasing gentrification pressures in neighborhoods like Sunset Park. Website: https://www.nyc.gov/site/nycha/index. page

New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD):

The New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) is responsible for implementing housing policies and programs to promote the preservation and development of affordable housing, enforcing housing quality standards, and supporting neighborhood revitalization across the five boroughs of New York City. HPD oversees a variety of initiatives aimed at addressing housing affordability, including the construction and preservation of affordable housing units, enforcing housing maintenance codes, providing rental assistance to low-income households, and promoting homeownership opportunities for firsttime buyers.

HPD works closely with community-based organizations, developers, landlords, tenants, and other stakeholders to address housing challenges and promote equitable access to safe, affordable housing for all New Yorkers. Through this comprehensive approach to housing policy and development, HPD supports the creation of vibrant, inclusive communities and improves the quality of life for residents across the city.

One key program offered by HPD is the Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP), which provides temporary financial assistance to low-income tenants who are behind on rent. ERAP covers up to 12 months of past-due rent and three months of future rent, as well as other housing-related expenses.

Website: https://www.nyc.gov/site/hpd/index. page

The New York City Department of City Planning (NYCDCP):

The department’s work in rezoning neighborhoods often incorporates provisions for mixed-income housing to address housing affordability concerns and foster diverse communities.

Website: https://www.nyc.gov/site/planning/ index.page

The New York City Department of City Planning (NYCDCP) is responsible for guiding the physical development of New York City. Its mission is to promote housing, economic development, and quality of life through strategic planning and zoning regulations. NYCDCP plays a crucial role in shaping the city’s long-term development by working on comprehensive land-use planning, ensuring efficient use of space, and implementing citywide and neighborhood-level plans. The department collaborates with city agencies and the public to create sustainable and equitable urban environments.

In terms of housing services, NYCDCP helps ensure that there is sufficient affordable housing across the city through land-use and zoning policies. It works to identify areas where new housing can be developed, promotes inclusionary housing policies that require affordable units in new developments, and supports initiatives that preserve existing affordable housing.

The Fifth Avenue Committee (FAC) is a nonprofit community development organization based in Brooklyn that has been addressing affordable housing, tenant rights, and community development since 1978. FAC focuses on improving the quality of life for low- and moderate-income residents by providing access to affordable housing, tenant organizing, and educational resources.

The organization works on a variety of projects, including the preservation and development of affordable housing units, tenant advocacy, and legal support for housing-related issues. FAC also runs programs aimed at preventing eviction and displacement, empowering tenants to fight for their rights.

In Sunset Park, FAC plays a significant role in providing housing services, particularly by helping preserve affordable housing in this rapidly gentrifying neighborhood.

They are involved in tenant organizing, supporting local residents facing housing challenges like eviction or rent increases. Through community engagement and advocacy, FAC ensures that residents have access to affordable and sustainable housing solutions. Their work also includes managing affordable housing properties and ensuring proper maintenance and repair for these units, offering a comprehensive approach to community development and housing stability. Website: https://fifthave.org/

The Urban Homesteading Assistance Board (UHAB):

The Urban Homesteading Assistance Board (UHAB), founded in 1973, is a nonprofit organization that promotes affordable cooperative homeownership for low-income tenants in New York City. Initially created to address the housing crisis during the fiscal downturn of the 1970s, UHAB has facilitated the development of over 30,000 affordable housing units in more than 1,200 limited-equity co-ops. The organization’s focus is on empowering tenants to take control of their housing, particularly in historically redlined neighborhoods such as Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Harlem. By offering technical assistance, tenant organizing support, and guidance on converting rental properties into co-ops, UHAB ensures long-term housing stability and access to affordable homeownership.

In Sunset Park, UHAB provides various housing services centered around tenant empowerment and legal advocacy. They assist tenant associations in organizing to fight against evictions, demand necessary repairs, and hold landlords accountable for poor housing conditions. UHAB’s eviction prevention efforts include organizing tenants and connecting them with legal resources, including support from the Right to Counsel campaign, which guarantees legal representation for tenants in housing court. Additionally, UHAB is involved in broader policy advocacy efforts to protect tenants and promote affordable housing solutions citywide, playing a key role in addressing housing challenges in gentrifying neighborhoods like Sunset Park. Website: https://www.uhab.org/

Enterprise Community Partners:

Enterprise Community Partners is a national nonprofit organization that has been advancing affordable housing and community development since 1982. Their mission focuses on financing and preserving affordable homes while promoting racial equity and community resilience. Enterprise played a key role in developing the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) and advocates for policies that ensure housing stability. The organization has helped create over 1 million homes across the U.S. and continues to collaborate with various stakeholders to expand affordable housing options, improve conditions, and provide services that support financial stability and community engagement.

In Sunset Park, Enterprise provides a range of housing services focused on affordable housing development and preservation. Their resident services include financial counseling, community engagement programs, and access to health and wellness resources to enhance tenants’ overall well-being. Additionally, Enterprise is active in policy advocacy, promoting tenant rights and affordable housing policies. They also support eviction prevention and emergency rental assistance through initiatives like Project Parachute and New York’s COVID-19 Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP), offering vital assistance to renters facing financial difficulties. Website: https://www.enterprisecommunity.org/

Center for Family Life is a nonprofit communitybased organization that has been serving the Sunset Park community since 1978. CFL’s mission is to support families and individuals by providing a range of social services, including housing advocacy, youth development, and workforce development. As part of the broader SCO Family of Services, CFL works closely with immigrant families and low-income residents, offering essential resources like counseling, after-school programs, and tenant organizing

initiatives. CFL’s housing services are focused on stabilizing families by preventing eviction, helping them navigate the housing system, and advocating for affordable housing solutions. In Sunset Park, CFL offers crucial housingrelated services to help families facing eviction or struggling with housing insecurity. Their tenant advocacy programs assist residents in understanding their rights and organizing for improved housing conditions. While CFL does not directly provide affordable housing units, they play an active role in eviction prevention, offering guidance and resources for families facing housing challenges. By collaborating with local organizations and tenants, CFL ensures that Sunset Park residents have access to the support they need to maintain stable housing. Website: https://centerforfamilylife.org/

Brooklyn Legal Services Corporation A:

Brooklyn Legal Services Corporation A (Brooklyn A) is a nonprofit legal organization that provides free legal services to low-income individuals and families in Brooklyn, with a focus on housing justice, economic development, and tenant advocacy. Brooklyn A works to ensure that vulnerable communities have access to legal support, particularly in cases involving housing disputes, evictions, and tenants’ rights. Their mission is to empower tenants to fight against harassment, displacement, and poor housing conditions, ensuring that residents can remain in their homes without facing illegal eviction or neglect from landlords. They also work with tenant associations to provide organizing support

to help renters collectively address housing issues.

In Sunset Park, Brooklyn A is involved in offering legal services to tenants who are facing eviction or dealing with landlord neglect. They provide legal representation in housing court and help residents fight against unlawful evictions. Their team also works on preserving affordable housing by advocating for policies that protect tenants from gentrification and displacement. Brooklyn A ensures that tenants in Sunset Park are wellrepresented and supported when it comes to asserting their rights to safe and affordable housing.

Website: https://bka.org/

Brooklyn Community Services:

Brooklyn Community Services (BCS) is a nonprofit organization that has been serving Brooklyn’s communities since 1866, with a mission to empower individuals facing social, economic, and health challenges. BCS provides a wide range of services to support vulnerable populations, including mental health support, workforce development, youth and education programs, and housing assistance. BCS plays a crucial role in helping individuals and families stabilize their housing situations by offering supportive housing programs. They focus on ensuring that low-income residents have access to safe, affordable housing, along with the necessary support to maintain stability in their lives.

In Sunset Park, BCS offers housing services that help individuals at risk of homelessness or eviction. Their programs include providing financial assistance to those struggling to pay rent, along with counseling and case management services to help residents navigate housing challenges. BCS also offers supportive housing for individuals with disabilities or those in need of long-term housing solutions. By addressing both immediate and long-term housing needs, BCS contributes to the overall well-being of Sunset Park residents, ensuring they have access to stable housing and supportive services.

Website: https://wearebcs.org/

Neighbors Helping Neighbors (NHN) is a nonprofit organization based in Brooklyn that focuses on housing justice, tenant advocacy, and financial empowerment for low- and moderate-income individuals. Their mission is to support tenants in maintaining stable housing by providing assistance with tenant rights education, financial counseling, and housing services. NHN works closely with tenants facing challenges such as eviction, rent increases, and unsafe housing conditions, helping them understand their rights and navigate housing-related legal processes. They also offer guidance on securing affordable housing options and assist first-time home buyers

in achieving homeownership through education and counseling.

In Sunset Park, NHN plays an important role by offering tenant support and advocacy services to residents who are at risk of eviction or displacement. They provide financial counseling to help tenants manage their housing expenses and avoid falling behind on rent, while also offering community engagement programs that empower residents to advocate for their housing rights. NHN is committed to preventing homelessness through eviction prevention programs and promoting long-term housing stability in Sunset Park. Their comprehensive services, including affordable housing support and tenant organizing, ensure that residents can remain in their homes and build stronger communities.

Website: https://fifthave.org/neighbors-helpingneighbors-2/

TakeRoot Justice is a nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing social and economic justice through legal services, advocacy, and community empowerment. They collaborate with grassroots organizations to provide legal support, particularly in the areas of housing, workers’ rights, and immigration. TakeRoot Justice focuses on addressing systemic inequalities by helping marginalized communities fight for their rights and access essential resources. In the realm of housing, they offer tenant organizing support, legal representation in eviction cases, and advocacy for affordable housing policies to prevent displacement and gentrification.

In Sunset Park, TakeRoot Justice plays a vital role in supporting tenants facing housing instability. They offer legal services to residents who are threatened with eviction or experiencing harassment from landlords. TakeRoot Justice also engages in community organizing efforts, helping tenants form associations to collectively advocate for better living conditions and rent protections. Their policy advocacy work aims to safeguard affordable housing and push for stronger tenant protections, ensuring that vulnerable residents in Sunset Park are not displaced due to rising housing costs or landlord exploitation.

Website: https://takerootjustice.org/

New York Communities for Change (NYCC):

New York Communities for Change (NYCC) is a community-based organization that advocates for social and economic justice across New York City. Their mission is to empower lowand moderate-income communities through grassroots organizing and advocacy, particularly in the areas of housing, workers’ rights, and environmental justice. NYCC plays a key role in fighting against displacement and gentrification, working to ensure that residents have access to safe and affordable housing. They work with tenants to organize against unjust evictions, rent hikes, and predatory landlord practices, striving to preserve the right of residents to remain in their communities.

In Sunset Park, NYCC is actively involved in housing advocacy efforts to protect tenants from eviction and ensure that affordable housing remains accessible to all residents. They provide tenant support through community organizing and policy advocacy, helping residents collectively push for stronger tenant protection and resist displacement pressures from gentrification. NYCC also focuses on eviction prevention by supporting tenants facing housing court cases and promoting policies that safeguard tenants’ rights. Their work in Sunset Park empowers the local community to fight for housing justice and secure long-term housing stability.

Website: https://www.nycommunities.org/

UPROSE is Brooklyn’s oldest Latino community-based organization, with a focus on environmental justice and community resilience. Founded in 1966, UPROSE advocates for climate justice, sustainable development, and community empowerment in Sunset Park and across New York City. While UPROSE’s primary mission revolves around environmental activism, they also address housing justice as it intersects with environmental concerns. The organization works to ensure that low-income communities of color, particularly those in Sunset Park, have access to healthy, sustainable housing and are protected from displacement caused by gentrification and environmental degradation. UPROSE believes that housing stability is an integral part of creating resilient communities that can withstand the impacts of climate change.

In Sunset Park, UPROSE supports housing justice by advocating for policies that protect residents from displacement while promoting sustainable development. They engage in community organizing, working with tenants and local groups to resist gentrification and ensure that housing development aligns with environmental sustainability goals. UPROSE also advocates for affordable housing that is resilient to climate impacts, recognizing that low-income communities are often the most vulnerable to both housing insecurity and environmental hazards. By combining environmental and housing advocacy, UPROSE plays a crucial role in ensuring that Sunset Park remains a community where residents can thrive without fear of displacement.

Website: https://www.uprose.org/

The Parent Child Relationship Association (PCRA) is a nonprofit organization dedicated to strengthening family bonds and supporting child well-being. Through family counseling, educational workshops, and advocacy, PCRA helps parents create stable, healthy environments for their children, with a focus on housing stability. Their services aim to address housing-related challenges and promote the overall well-being of families, ensuring children are raised in secure and supportive homes.

In Sunset Park, PCRA assists families facing housing instability by connecting them with

affordable housing resources and emergency rental assistance. They also provide counseling to help families maintain stable housing and resolve issues that could contribute to eviction. By offering holistic support, PCRA helps families in Sunset Park achieve long-term housing stability and stronger relationships.

Website: https://www.pcr.nyc/

Mixteca Organization, Inc. is a nonprofit dedicated to supporting the Latinx immigrant community in Brooklyn through programs focused on health, education, and housing. Mixteca offers a wide range of services aimed at empowering immigrant families, helping them navigate issues related to housing, health care, and legal rights. They provide workshops, educational resources, and direct support to assist community members in securing safe, stable housing and improving their overall wellbeing.

In Sunset Park, Mixteca focuses on providing housing support to Latinx immigrants, offering services such as tenant education, legal assistance, and connections to affordable housing resources. They help tenants understand their rights and work to prevent eviction and displacement, particularly for families who are at risk of losing their homes due to gentrification or landlord neglect. Mixteca also engages in

advocacy efforts to protect immigrant tenants from housing insecurity and ensure that they have access to stable, affordable housing in Sunset Park.

Website: https://www.mixteca.org/

Churches United for Fair Housing (CUFFH) is a grassroots nonprofit organization that works to advance housing justice and prevent displacement in Brooklyn. CUFFH was founded with the mission of empowering local communities, especially communities of color, to fight against the forces of gentrification and advocate for affordable housing. They work in collaboration with churches, community leaders, and local residents to organize around housing issues, provide tenant advocacy, and ensure that vulnerable populations have access to affordable and stable housing. CUFFH also focuses on fostering community engagement and building collective power to address the broader structural issues that contribute to housing inequality. In Sunset Park, CUFFH provides a variety of housing-related services, including tenant organizing, policy advocacy, and community outreach. They assist residents facing eviction, helping them understand their rights and navigate legal challenges. Additionally, CUFFH advocates for the development of affordable housing and works to resist displacement by pushing for policies that protect longtime residents from the pressures of gentrification.

Through their organizing efforts, CUFFH plays a critical role in ensuring that residents of Sunset Park have access to safe, affordable housing.

Website: https://www.cuffh.org/

Brooklyn Tenants United:

Brooklyn Tenants United (BTU) is a grassroots organization focused on empowering tenants to fight for their rights and ensure safe, affordable housing across Brooklyn. BTU works with tenants, community groups, and advocacy organizations to address issues such as rent increases, eviction, and poor housing conditions. Their mission is to support tenants in organizing for better housing policies and protection against predatory landlords. BTU focuses on tenant education, ensuring that residents understand their rights and have the resources to defend themselves in housing court or during disputes with landlords.

In Sunset Park, BTU provides critical support to tenants at risk of eviction or displacement. They organize tenants into associations to collectively address housing issues and advocate for stronger tenant protections. BTU also provides resources to help tenants navigate legal processes related to housing and eviction prevention. Their work ensures that residents of Sunset Park are not forced out of their homes due to gentrification or unjust housing practices.

The NYC Community Land Initiative (NYCCLI) is a coalition of grassroots organizations, housing advocates, and community members working to advance community land trusts (CLTs) as a tool for achieving housing justice and long-term affordability. NYCCLI promotes the development and expansion of CLTs, which allow communities to collectively own and control land, ensuring that housing remains affordable and is protected from market-driven speculation. The initiative focuses on addressing displacement, supporting tenant rights, and creating sustainable housing solutions that prioritize the needs of low-income residents.

In Sunset Park, NYCCLI supports efforts to establish community land trusts as a way to empower residents and preserve affordable housing. By helping to create CLTs, NYCCLI ensures that land and housing remain under community control, preventing displacement and promoting long-term housing stability. They also provide technical assistance and education to local groups interested in forming CLTs, advocating for policies that support these efforts and protect low-income residents from gentrification.

Website: https://nyccli.org/

The first housing cooperatives in the US were established in Sunset Park by Finnish immigrants in the aftermath of World War I. As one of the birthplaces of the modern cooperative movement, this neighborhood is a uniquely important site for revisiting the history of a form of social organization as old as our modern industrial economy, with a storied past both in New York City and across the world. Below we examine the role that cooperatives could play in addressing the contemporary crises that threaten working class immigrant communities like Sunset Park: rezoning, gentrification, landlord abuse, and the general lack of access to quality housing.

A cooperative is an organization of people owned and controlled according to collective cultural, economic, social, or material needs. Cooperatives are a value-based model for ownership. Their guiding principles typically include:

• Joint-ownership: owned and governed by its members

• Democratic control: each member possesses equal voting power

• Voluntary/open membership: anyone is welcome to join, typically with a required buy-in

• Social and environmental responsibility: prioritize sustainability, fair labor practices, and local development

Cooperatives can assume many different forms:

• Worker cooperatives: businesses owned and managed by their employees

• Consumer cooperatives: businesses owned and managed by those who consume goods and/or services provided by the cooperative eg. cooperative grocery stores

• Producer cooperatives: businesses where producers pool their output for their common benefit eg. agricultural cooperatives

• Service cooperatives: provide services to their members rather than goods eg. credit union, healthcare cooperative, utility cooperative

• Social cooperatives: These include childcare centers owned by parents or caregivers, youth cooperatives that manage city services, and businesses owned and managed by people with disabilities.

How is cooperative housing a potential response to Sunset Park’s community challenges?

Cooperatives are an alternative model to the private ownership of housing which leads to competition, exclusion, and exploitation. They aim to meet the needs of their members, rather than maximize profit–they generate community vitality through the localization of profit-sharing. They entitle control and decision-making to those most affected.

The challenges facing Sunset Park are endemic to a “housing crisis” which is affecting large parts of New York City. But what is often painted as perhaps a crisis of housing supply and an overabundance of demand (the narrative of private development) is actually a crisis of power and organization of working class tenants and their ability to resist oppressive market forces. Workers and tenants have built an organized response to their exploitations in the centuries since the Industrial Revolution. The ability for this group to self-organize and advance its own interests (through trade unions, cooperatives, mutual aid societies, etc.) has played a key role in beating back what we now know as gentrification and displacement. We must understand contemporary housing struggles within the history of the global and citywide cooperative movement.

The origins of cooperative movements stem from a response to the inequalities of private property, whereby the benefits of a property largely accrue to an individual or group of private owners. For example, land is held by a landowner, but worked upon by many agricultural workers, or housing which has many residents who all must pay rent to a single landlord or corporation.

Private property, in opposition to smallscale individual ownership, the commons, or collective property, dates to the beginning of class society around 5,000 years ago. But for most of written history, the vast majority of property forms have been individual or collective. These forms of property survive in the social organization carried on in indigenous societies, or in the survivals of small subsistence farming in various parts of the globe.

The modern cooperative movement draws from these pre-capitalist examples, but has mainly emerged in the West out of the worker’s movement, or the response of the new waged working class to its oppression under the capitalist system of production, and drawing strength from the necessity of the working class to cooperate and combine in order to fight for its own interests, as a class defined by its lack of access to property.

In fact, the modern generalized form of private property under capitalism, in which the great mass of people are forced to work and live under the direction of an owner of privately held property, is relatively new. The widespread privatization of land and housing dates to the large-scale urbanization that followed the Industrial Revolution of the 18th-19th centuries, spurred on by the enclosure of the rural commons.

The first cooperatives emerged on a small scale, with the first known cooperative store established in England in 1769 among a group of weavers. It was not until the organizations of The Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers, established in 1844, which organized on a set of guiding principles which helped to outline the basis for sustainable cooperative organization, that the cooperative movement gained a firm footing, forming the basis for the principles on which cooperatives around the world continue to operate.

The original Rochdale Principles:

• Open membership

• Democratic control (one person, one vote)

• Distribution of surplus in proportion to trade

• Payment of limited interest on capital

• Political and religious neutrality

• Cash trading (no credit extended)

• Promotion of education

The modern socialist movement, which dates its origins to the French Revolution (1789-1799), emerged alongside the workers movement in response to the perceived evils of private ownership of property. Within this movement there was fierce debate over not only the nature of the struggle against property, but also about the role of working class cooperation and cooperatives in the process of social change.

Robert Owen | 1771-1858

Sometimes called “the father of the cooperative movement” was a British factory owner who thought that establishing utopian communities was the key to overcoming private property, in which workers had access to decent quality of life and education, and had the freedom to cooperate and self-govern. The first cooperative store was established at his landmark experiment in New Lanark, Scotland in the early 19th century, and he theorized the creation of large-scale cooperative settlements. But Owen also thought that securing the financial support of the owning class (of which he himself was a member) was essential to working class emancipation, and he was largely spurned by this group. His further experiments in the United States failed, but his theories helped to motivate the budding cooperative and socialist movements.

Karl Marx | 1818-1883

A major political thinker of the mid-19th century and down to the present day. He thought that the working class could only emancipate itself by uniting to organize itself politically as well as economically, with the end of taking political power away from the capitalist class. Unlike Owen, Marx thought that working class independence and initiative was of the utmost importance, and unlike Proudhon, he saw the cooperative movement as one part of the self-organization of the working class for its own interests, necessary but not sufficient for overcoming private property.

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon - was one of the major socialist thinkers of the mid-19th century. His political thought, known as “mutualism” held that establishing cooperative forms of organization could overcome capitalism itself, and he did not believe much in fighting for political change or organization. Alongside Owen, he thought that the evils of private property largely resided in the dishonesty and thievery of individual bankers and industrialists, and that the organization of cooperatives could gradually overcome the system of private property.

The Cooperative Commonweath

In the American socialist movement of the turn of the 20th century, the future socialist society was often referred to as “the cooperative commonwealth.” The form and nature of working class cooperation remains a key part of imaging a world beyond private property.

The cooperative movement itself, however, while driven by utopian imaginations of a better world, has mainly served the structural function of fighting for a better lot for the working class within a capitalist system dominated by private property. This has defined the complex and evolving fortunes of the movement over the centuries, underpinned by a similarly evolving and complex relationship between working class self-organization, state policy, and long-term changes in the social fabric of the economy and society.

Influenced by the English co-operative movement, housing cooperatives were established in 1862 in Hamburg and have been making a comeback in recent decades. In 2002, the Federal Government set up an Expert Commission with the objective to develop and strengthen housing co-operatives as a third alternative to rental housing and ownership. WagnisART Co-operative in Munich is a prime example. Constructed on a former art colony in 2007, wagnisART was designed to create a collaborative urban existence in a creative and active neighbourhood where the wellbeing of its inhabitants is prioritised. Its five buildings are connected by a public courtyards and semi-public elevated passages. Known for its cluster apartments where one to three residents have a private kitchenette, bedroom and bath, and share a community kitchen and joint living space for up to 11 people. In addition, the complex has different facilities such as art studios, medical surgeries, offices, a café, workshops, a sewing room, rehearsal rooms, an indoor playground and guest apartments.

As early as the late Qing Dynasty, cooperative housing has had a presence in China. Initially introduced through the Gungho movement and later reinforced by the PRC during urban and rural collectivization, the success of co-operative, work-unit housing can largely be attributed to state backing. At the peak of collectivism in 1956, 96% of farming households were part of a cooperative. While economic reforms and the transition toward a market-based housing system have muted the state’s priority for cooperative housing, its legacy lives on in rural areas. As intermediaries between smallholder farmers and financial institutions, farmer-specialized cooperatives pool resources, enhance farmers’ bargaining power and improve their access to credit and loans—opportunities that would otherwise be difficult to secure due to a lack of collateral and credit history. The growth of farmer specialised cooperatives can be attributed to the Farmers’ Specialized Cooperative Law, first passed in 2007, which formalized the creation and operation of farmers’ cooperatives, granting them legal status and enabling them to engage in activities like credit facilitation, resource sharing, and collective purchasing.

The housing cooperative movement in Uruguay is known for its direct democracy and active participation amongst the community. These characteristics are playing an important role in the countries current housing reficit, where the country’s total permanent housing stock is slightly over 1.1 million, while the total population is less than 3.5 million. To create more livable and dignified housing, the movement the cooperative housing model centers around supporting low-income families building and managing their own homes through cooperatives. The Uruguayan Federation of Mutual Aid Cooperatives (FUCVAM) has been instrumental in strengthening the right to housing by uniting cooperatives under the principles of mutual aid and collective property. For some co-operatives, like the José Pedro Varela complex, the cooperative model has extended over the entire neighbourhood. Named after the Uruguayan sociologist and educator, the José Pedro Varela complex united dozens of co-operatives and includes public education facilities that the surrounding neighbourhood can access.

The roots of cooperative landholding in Mexico can be traced to indigenous traditions and were formalized in the 1917 Constitution (Article 27), which focused on land redistribution to empower rural communities. Under the ejido model, land remained state-owned but was allocated to communities for collective use, where members could farm individual plots without full ownership. Ejidos remain an important part of Mexico’s agrarian system, reflecting ongoing support for cooperative principles. A notable example is the Palo Alto Housing Co-operative, established in 1940 by families who built homes on a former sand quarry in the Bosques de las Lomas district. Despite the surrounding development and gentrification, the cooperative has preserved its community through collective ownership and its organizational structure.

With origins stemming from the Taino Indians, an Indigenous people of Caribean, the long tradition of cooperatives in Puerto Rico has led to the development of various experimental co-opertive models. From prisoner owned art co-operatives like Cooperativa de Servicios ARIGOS, to financial co-operatives like Co-op Moca that served as a lifeline to its members after Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico has extensive legislation that support the development of cooperative ventures. One prominent housing cooperative is the Cooperativa de Vivienda Ciudad Universitaria, which was established to provide affordable housing for university students and faculty. Located in Trujillo Alto, the co-op follows a participatory model where residents are involved in decision-making regarding the maintenance and management of the property.

New York City’s cooperative housing movement has emerged and evolved through a complex interplay between working class self-activity, state policy, and larger structural transformations in the global political-economy and its local impact on the City. It has broadly unfolded in three historical phases, corresponding to the worker cooperative movement of the 1910s-30s, the post-war state-directed construction of cooperatives under the Mitchell-Lama program and federal financing in the 1950s-60s, and the urban homesteading movement after New York City’s financial crisis in the post-1970s era. All of these phases of the movement have overlapping timelines of implementation and legacies that come down to the present day.

State Housing Act 1926, Establishes a state-controlled bank to finance low-rental housing and authorizes tax abatements

US Involvement in WW1 1917-1918

First Worker Housing Cooperative 1917 Under the Finnish Home Building Association

Amalgamated Housing Cooperative Established 1927, established trade-unions as major institutional backers for worker cooperatives

Great Depression 1929-1941

US Involvement in WW2 1941-1945

Worker Cooperatives | 1910-30s

New York City’s cooperative housing movement has evolved through a complex interplay between working class self-activity, state policy, and larger structural transformations in the global political-economy. It has broadly unfolded in three historical phases, corresponding to the worker cooperative movement of the 1910s-30s, the post-war state-directed construction of cooperatives under the Mitchell-Lama program and federal financing in the 1950s-60s, and the urban homesteading movement after New York City’s financial crisis in the post-1970s era. All of these phases of the movement have overlapping timelines of implementation and legacies that come down to the present day.

In the aftermath of the 60s and 70s mass abandonment and foreclosure crisis, including urban renewal policies, thousands of empty units were left in city’s hands. Grassroots groups began to push for public to cooperative ownership, given that the rehabilitation of the units could be financed. The Urban Homesteading Assistance Board (UHAB) was founded in 1973 as an organization promoting and financing the development of urban cooperatives, or homesteads. A more radical wing of the homesteading movement, the squatting movement, also emerged as a

form of cooperation that rejected state backing and legal recognition. The Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD)’s Division of Alternative Management Programs (DAMP) emerged as the state-side institutional backer of public-cooperative transition. However, as neighborhoods stabilized, real estate developers began to buy up and privatize homestead cooperatives. Housing Development Fund Corporation (HDFC) cooperatives continue to this day as limitedequity organizations, whose stability is rooted in a city regulatory agreement established to standardize cooperative management which to some extent limits privatization.

United Housing Foundation Established 1951, Real estate investment trust that constructed some of the largest co-op developments in the City

The Limited-Profit Housing Companies Act 1955, “Mitchel Lama” established the process for municipal acquisition by eminent domain, enabling developers to build low- and middle-income housing.

Urban Homesteading Assistance Board (UHAB) 1973, Non-profit involved with promoting and financing the development of urban cooperatives, or homesteads

First NYC CLT established in the LES 1994, Cooper Square CLT

NYC Fiscal Crisis 1969-1976

“Mitchell-Lama” State-directed Cooperatives | 1950s-60s

In the immediate post-Second World War period, trade-union sponsorship maintained a significant factor in cooperative housing development, culminating in the founding of the United Housing Foundation (UHF). The 1955 “Mitchell-Lama Act,” a state-directed response to the post-war housing shortage incentivized the construction of cooperatives through tax exemptions and low-interest loans. Enormous housing developments, like Co-op City in the Bronx, were developed under this Act, often through demolition of properties and displacement of existing residents. During this period, federal anti-poverty and housing financing also began to have an influence on cooperative housing development. In the long-term, pressures like gentrification have transitioned many Mitchell-Lama cooperatives towards market-rate deregulation.

Cooperativism has been central to Sunset Park’s immigrant communities since its formation. At the onset of the last century, Finns started settling in the area and establishing community centers, churches, newspapers, businesses and political groups following cooperative principles. The driving force behind the local cooperative movement was a Finnish man called Matti Kurikka who was an advocate of a particular strain of utopian socialism and a leader in the growing socialist moment in his homeland. He came to Sunset Park in 1909 and started working alongside other Finns on a housing cooperative movement responding to the worker housing conditions of the time.

The idea of both reducing the cost of rent collected by landlords and increasing their quality of life by constructing housing under a cooperative model emerged at the Brooklyn Finnish Socialist Club. In 1916, inspired by Kurikka’s ideals, a group of sixteen families founded the Finnish Home Building Association and established the first housing cooperative for workers in the country with a model based on shared ownership and limited equity. It was erected at 816 43rd Street under the name Alku, which means “Beginning” in Finnish. A second building named Alku Toinen, which translates to “Second Beginning”, followed next to it. Without antecedents in the country, the Finnish co-ops, as they are locally called, were perceived as revolutionary in all regards. The tenements of the time and the cooperative housing buildings had nothing in common except that both housed workers. In the coming years, over 24 Finnish co-ops were built around the park. The co-ops, mostly fourstory buildings with central yards, got names

with valuable meaning to the growing Finnish working-class as Hikipisara (Drop of Sweat) and Kyopeli (Old Maid’s Home). By the early 1980s, the buildings were still occupied by the original owners or their descendants and the price of the few units available was relatively low. In recent years, these coops have become highly desirable and sold at high prices. However, most of them continue to be owned and managed collectively.

In the mid-1970s, when housing abandonment plagued the neighborhood, collective efforts took place once again to save Sunset Park’s neglected, vacant, and foreclosed properties. The community efforts took advantage of the tenant-led programs sponsored by the newly formed Division of Alternative Management Programs at the NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development. Rooted in the squatter movement, the Urban Homesteading, Sweat Equity, Community Management, and Tenant Interim Lease Programs rehabilitated entire multifamily buildings across the city and turned them into limited-equity housing cooperatives. Coop buildings were established as special purpose corporations known as Housing Development Fund Corporations (HDFC) which were legally required to serve low-income individuals and families. At least nine cooperative buildings with over 225 units remain from that time in Sunset Park. Considering their formation years, between the 1980s and 1990s, and some of the housing co-ops’ names, it is estimated that they were established mostly by the Latinx community. During this period, other HDFCs were also created in the area by non-profit organizations to serve specific community purposes such as senior and transitional housing.

In 2006, another wave of cooperativism emerged in the neighborhood galvanized by the Worker Cooperative Development Program launched by the Center for Family Life. The program was introduced to meet the employment needs of the local immigrant community. Facing discrimination and abuse in the labor market Latin American immigrant women rapidly organized and established the first two cooperatives: We Can Do It! and Beyond Care. Respectively, these cooperatives provide housecleaning and childcare services across Brooklyn. In the following years, over 13 worker cooperatives mostly led by immigrants and minorities were established offering different services, from catering, tutoring, and senior care to dog walking, construction

Social housing is permanently and deeply affordable, under community control, and most importantly, exists outside of the speculative real estate market. Social housing can exist in different forms. It can be owned by public entities, residents or mission-driven nonprofits. It can be occupied by renters or homeowners. Some of its characteristics include:

• Socially owned

• Permanently decommodified

• Permanently affordable

• Under community control

• Anti-racist and equitable

• Sustainable

• High quality and accessible

• With tenant security

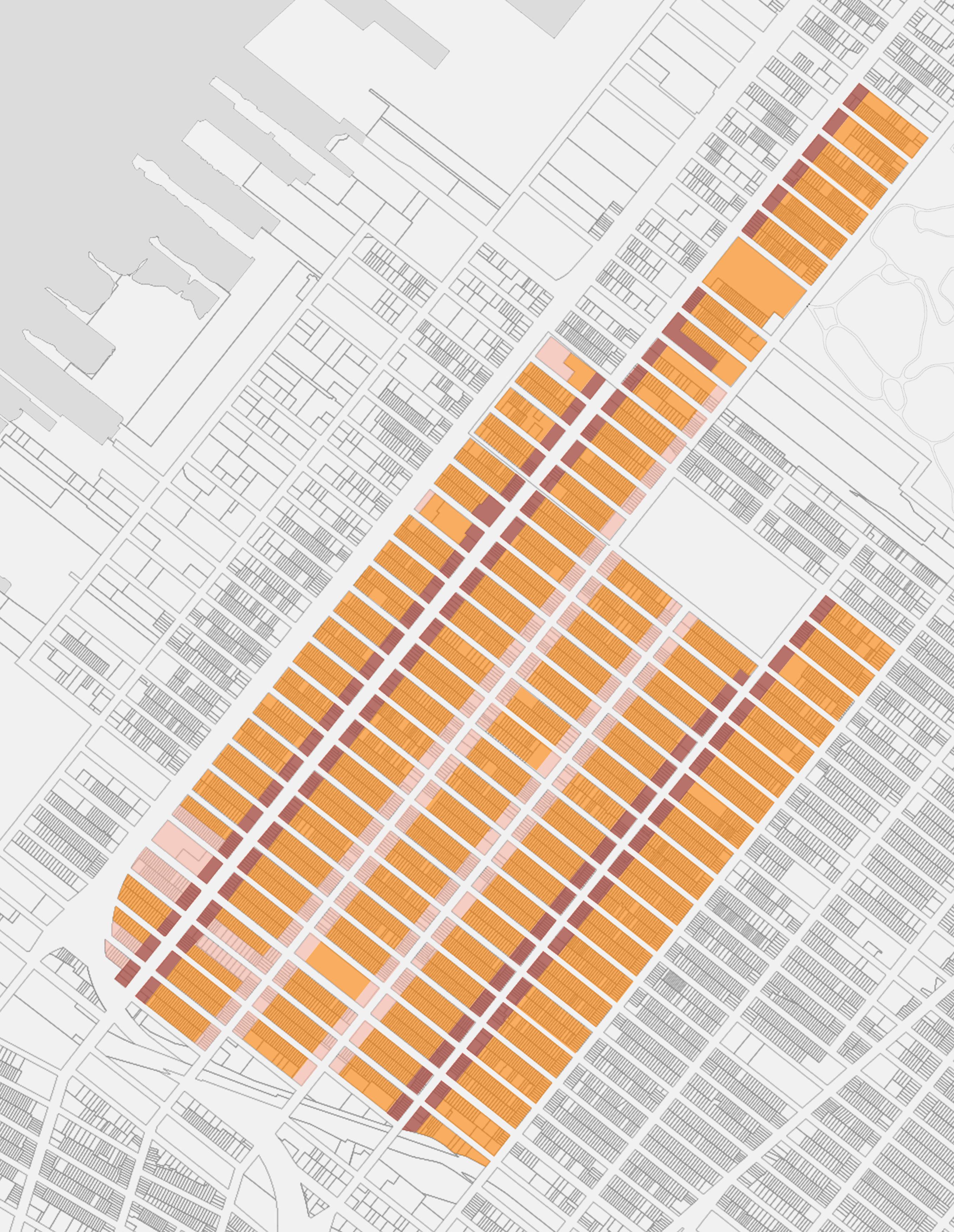

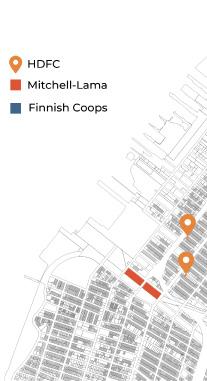

Sunset Park’s housing stock was directly shaped by New York City’s cooperative housing movement(s). This map visualizes the existing mixture of HDFCs, MitchellLama, and Finish Cooperative housing.

*Housing Development Fund Corporation. See next page for more information.

*These buildings are technically outside of Sunset Park’s neighborhood boundary.

The table below compares the characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages of the different cooperative organizations, within New York City, that facilitate or support each housing model. It also lists the

Housing Development Fund Corporation (HDFC) cooperatives

Mutual Housing Association (MHA)

Community Land Trust (CLT)

Market Rate Coop

Limited Equity Coop

Mitchell-Lama

• Resident-owned apartments

• Shareholders own an equal number of shares

• Shareholders elect a Board of Directors

• Limited Equity Corporation

• Nonprofit, community-based organizations that develop, own and manage housing

• Turn illegal squatters into legal homesteaders

• Government assistance in property acquisition

• Sweat equity; tenant ownership

• Buildings are owned and used by organizations, individuals, and businesses

• The CLT owns the land and works to ensure it is used in ways that benefit the community

• Residents are the sole owners through a corporation, which owns the land and buildings

• Members democratically govern the cooperative and elect board of directors to oversee operations.

• 1 Household/1 Member/1 Vote

• Residents are the sole owners through a corporation, which owns the land and buildings

• Members democratically govern the cooperative and elect board of directors to oversee operations

• 1 Household/1 Member/1 Vote

• Apartments are sold or rented through waiting lists kept by each development

• Maximum income limits differ for federallyassisted rental and cooperative developments

• Targets middle-income

Advantages

• Federal and State

• Required to meet

• Shareholders have a profit from selling longterm affordability

• Cooperative values/principles

• subsidies and tax

• Democratically governed

• Tenants gain ownership

• Reduce market pressure

• Democratic control

• Affordable in perpetuity

• Residents have the particular dwelling

• Regulation on sale affordable