19 minute read

MEET THE COVID KIDS

The Sheet Metal Workers Training Centre flexed its resilience muscles during COVID using technology, ingenuity, and first class support for its students

By / Jessica Kirby • Photos courtesy of SMWTC

Pick up any newspaper, open any news app and there is no shortage of COVID-19 news—most of it disheartening. In that climate, it can be hard to remember that with upset comes opportunity and with obstacles come solutions. The Sheet Metal Workers Training Centre in Vancouver, British Columbia, created something positive from the circumstances that arose from the pandemic, and though it wasn’t always easy, managed to keep its doors open and students safe and learning, while making important steps towards adopting the future of education.

Back in March when British Columbia went into initial restrictions, there were 41 students attending SMWTC in Levels 1, 2, and 3, and there was a lot of fear. Including the instructional staff, there were 48 in the building at once, which met the provincial health officer’s (PHO) 50-person limit and meant the school could stay open.

“At full lockdown, the limit was only five, so in a weekend everything changed,” says Training Coordinator Jud Martell. “We sent those students home on Friday and told them to wait for an email on Monday. On Monday we taught everyone how to Zoom and had a Zoom meeting in which I introduced the new normal moving forward.”

And a new normal it was. Martell and the instructors spent the weekend putting online the materials students would require to complete the final two weeks of their training. They cobbled together a learning package, scrounged loaner computers for those who didn’t have them, and provided access to the server for all then-current students—a cohort they nicknamed “The COVID Kids”.

“We feel like this was the safest boat to be on in the construction trade during that time,” Martell says. “Other schools shut the doors and told students to go away. They didn’t even get to pick up their things.”

In many ways, the pandemic expedited a situation already

in the making—the digitization of part of the training centre’s offering. Over the past two years, Martell has inched the centre closer to accepting more technological advancements, a mission that started with implementing a server the staff could access remotely. The centre’s COVID response hinged on that implementation.

Getting through those first few weeks required several pivots or areas of adjustment. The first pivot was shutting early, following the decision of the trustees and the provincial health officer’s (PHO) directives.

“We had one week’s notice and then went on to discuss with the training board what closing would look like,” Martell says. “The next pivot was to develop a way to ensure 70% completion by offering the final two weeks of instruction online.”

The third pivot was helping students stay in school and collect unemployment insurance because they would otherwise have to return to work in the middle of a crisis where their health and safety was not ensured onsite.

The fourth pivot was extending the technical training as far as possible, which engaged the students in helping the centre design its remote capabilities and online modules and test its online platforms.

Although all of those decisions were made with the utmost consideration, not everyone reacted favourably. “There was a strong reaction from some who believed we were making the wrong call,” Martell says. “We shut down our socials for months. I truly believed that the best course was not to get out of the boat. My own son was in that class, so there is no doubt I made each decision thoughtfully.”

That was in March and April, the heart of the panic. After the initial action, SMWTC cancelled the remaining class schedule for 2020-2021 and spent several weeks informing students that a new schedule would be developed once it was safe and appropriate to do so. Because the classes are concurrent, all 40 classes scheduled between April 2020 and early 2021 had to be cancelled.

“At that time, some people still thought the whole thing would be over in June,” Martell says. “The plan was to see if we could come up with a safe, sustainable way forward.”

They scheduled a Level 4 class to begin June 15. It would run for four weeks remote learning and three weeks in the school, knowing that if necessary, the students could achieve 70% completion with the remote portion alone.

“That is how we built in resilience,” Martell says. “The idea was to get Level 4 through and get them to write the interprovincial exam (IP).”

safety meetings.

On June 15, the SMWTC started three classes of eight Level 4s. It began with a Zoom meeting that included 30 people. They covered COVID protocol to train onsite, gave everyone iPads and computers on loan, and set a goal to write the IP on July 31.

The staff and instructors spent four weeks designing the online learning modules and developing protocol for bringing the students in. That meant considering social distance, helping people feel comfortable, and having regular safety meetings.

“On July 31, we held a graduation ceremony—everyone graduated in masks and people came and sat outside to watch from the lawn and parking lot,” Martell says. “The very next day we had three separate locations of eight each writing the IP, and we heard back shortly after that all 24 passed. In ten years, if those 24 are the leaders of our industry, we will be in good hands.”

On August 24, SMWTC started Level 1 and Level 2 classes running in parallel. A week later, the Level 3s started, and once again 48 students in total were remote or in-person learning. Making that work meant hiring six instructors and redesigning the entire space to have separate upstairs and downstairs areas where each class will only be on one level at a time. The schedule has 24 online and 24 in-class at one time, alternating by the week. Into October, three more classes—a Level 1, a sheet metal Level 3, and an architectural Level 1—began to finish the year.

Looking forward, SMWTC is leveraging its successes and setbacks during this transitional phase to begin offering its drafting portion online. As of the time of writing, Martell has secured a partnership with Microsoft that will allow the training center to receive 300 student software seats. A partnership with AutoDesk provides 1,200 student software seats. Martell is currently in discussions with Lenova about a hardware donation.

“Standardizing the hardware and software is a major goal right now,” Martell says. “We need that so there is always a touchstone students can come back to if they get lost.”

Online learning has been the saving grace for the training center, but it also has challenges. It is harder to identify online when a student is struggling, and having instructors on-hand to motivate and give individual feedback is irreplaceable. As well, students’ physical fitness suffers when they are not onsite.

“We give students lots of breaks and asked them to exercise, go for walks, and look after their health,” Martel says. “We have a dedicated instructional staff that can’t check in with students the same way. There is also a provincial health emergency going on and the background health emergency—the opioid crisis—all coming together at once. It definitely isn’t easy.

“We are working in the ‘new normal’ while taking all of this into account and putting our students’ health first,” Martel says. “The iTi has been the most dedicated partner through all of this, implementing incredible, dedicated support to the training center every step of the way.

“We have built resilience and flexibility into our programming and will continue to adjust things as necessary so the students get the most out of their training and we get the most out of the way they are helping our school evolve and grow.” ▪

Jessica Kirby is a freelance editor and writer covering construction, architecture, mining, travel, and sustainable living for myriad publications across Canada and the United States. She can usually be found among piles of paper in her home office or exploring nature’s bounty in British Columbia’s incredible wilderness.

Will Your Organization (finally) Achieve Inclusion and Diversity?

By / Alaina Love This article was originally published on SmartBrief on Leadership.

I recently had a frank conversation with colleagues about the struggle we’ve observed our clients experiencing with achieving true inclusion and diversity (I&D) in their organizations.

While our first instinct was to discuss possible solutions to what seems like an insurmountable problem, we had to admit that I&D is an issue fraught with complexity. “Most organizations say they believe in inclusion and diversity, but we believe that workplace intention and commitment must be met with action, or no sustained change will be possible,” said CB Bowman, CEO of Workplace Racial Equality.

Solutions, we concluded, needed to be holistic, address the systemic roadblocks that prevent inclusion from becoming a way of life inside organizations, and acknowledge that interpersonal blind spots can foster them.

“In all of my years working with leaders and teams, I’ve not seen any sustained and consistent improvement in my client’s success with creating real inclusion and diversity,” lamented Tony. As an executive coach of C-suite leaders, Tony found that he was frequently addressing this challenge with his clients, particularly over the last six months, as social justice matters have become more evident around the world and more widely reported in the media.

“As a white male talking to mostly white male clients, I’m just not sure of how best to advise them,” he admitted.

As our small group began to unpack possible solutions, we structured a framework for thinking about the major organizational and leadership components that would need to be part of any I&D solution, regardless of organization type. They include the following:

Board commitment

The governance body of any organization has ultimate responsibility for all matters that affect the success or failure of a business. When a company experiences major manufacturing, product or sales issues, those challenges are raised and monitored at the board level until they are addressed. These are the kinds of issues that influence shareholder value, market position, and customer satisfaction.

While inclusion and diversity should be no exception as important issues, they first require appreciation among the board for their value to the business beyond that which is morally, legally, or ethically appropriate—an appreciation that puts I&D on par with product development and sales growth.

When an organization is struggling with achieving meaningful improvement in the diversity of its workforce

and the inclusion of a range of people and viewpoints in the dialogue of the business, the board plays an essential role in resolving this difficulty.

Leadership development

No real improvement in the area of I&D is possible without an aware, educated and impact-driven leadership group. Much of what has been accomplished in I&D thus far has focused on awareness—most recently in the form of unconscious bias training and other awareness initiatives—yet more is required. Around the subject of inclusion and diversity, our group of colleagues arrived at a few important conclusions through our analysis of the leaders with whom we have worked.

Many leaders do not know themselves well when it comes to their understanding of the tenets of race, ethnicity, and culture that have shaped their mindset as it relates to people different from themselves.

Many leaders shy away from the “unmentionables” and struggle with the deep and potentially divisive discussions that would improve their capacity to appreciate others’ life experiences. Fear, and the lack of safe spaces and processes to have tough conversations about what is happening in our world and our workplaces, is preventing leaders from doing the important work required to understand the current state. This understanding includes the cultural experience for diverse people in the organization and the hurdles they leap (that others don’t) just to come to work in the morning. Developing true subject knowledge in this area is critical for creating a leadership team that can foster and sustain a diverse and inclusive culture. Without it, leaders cannot begin to imagine the new possibilities that they have the power to create, whether internally or in the surrounding community.

Until it becomes personal in some way, there are leaders who do not feel the need to transform. They hold on to systems and long-established workplace norms because they are, on some level, benefitting from them. Until leaders shape cultural systems in a way that better balances the benefits for everyone, attracting and retaining diverse talent will continue to be a challenge, and sustained change will be nothing more than wishful thinking.

Transformational change capability

As we continued exploring our framework, it became clear that achieving I&D requires a large-scale transformational change process in most organizations. Noel Tichy, professor of management and organizations at the Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan, would say these processes are like creating a “revolution” inside the organization. All successful revolutions, he asserts, require control of the police, the media, and the schools.

As it relates to I&D, it matters how an organization monitors and sets examples around how individuals are valued and included. In essence, how the organization polices behaviors and fosters fairness in systems and processes determines what becomes acceptable as cultural norms.

What are the messages and stories that get shared in your organization? This is the “media” that influences how others perceive the I&D transformation that’s underway in the company. How can you encourage and empower your workforce to put these ideas into broader practice? By highlighting the organization’s success stories, learning moments, and examples of diverse viewpoints, you help others understand how inclusion is making a difference in the business.

It’s important as a leader to help all employees learn about themselves and develop an appreciation for individuals who may have had different life experiences. Do you have “schools” in place (formal and informal) where your teams can gain greater exposure and experience across various dimensions of diversity, including cognitive diversity? Are there opportunities and tools for teams to practice inclusion, not just talk about it?

Finally, do you have a prepared cohort of leaders who are equipped to lead a transformational change inside the organization and within the community it serves? Achieving sustained improvement in inclusion and diversity requires knowledge and capability in change leadership and an appreciation for the complex suite of solutions essential for ongoing improvement.

Without a doubt, it also requires courageous leadership. Are you ready to make it happen? ▪

Alaina Love is CEO of Purpose Linked Consulting and co-author of “The Purpose Linked Organization: How Passionate Leaders Inspire Winning Teams and Great Results” (McGraw-Hill). She is a recovering HR executive, a global speaker and leadership expert, and passionate about everything having to do with, well, passion.

The Electric Future

Northwest Sheet Metal had the human powered expertise and state of the art technology to pivot in chaotic times

By / Jessica Kirby • Photos courtesy of Northwest Sheet Metal

The words “agility,” “nimble,” and “pivot” have become commonplace these past several months, and in conversations about a new project from Northwest Sheet Metal this is no exception.

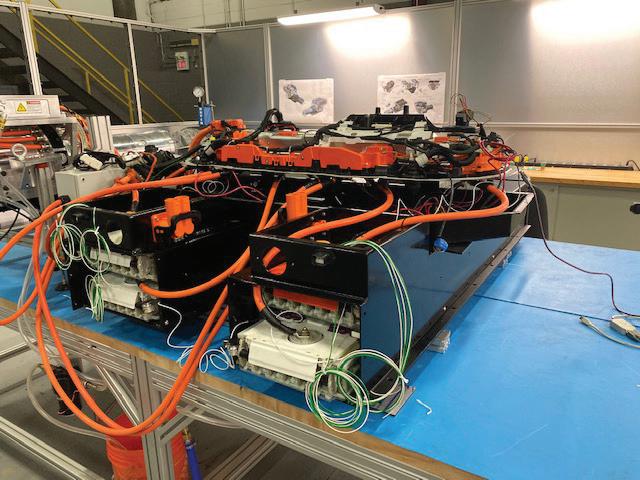

The Vancouver, British Columbia-based contractor took on construction of battery and engine boxes for an electric vehicle powertrain prototype designed by powertrain engineering firm Litens Automotive, which is headquartered in Toronto, Ontario. The system was constructed as a one-off research and development platform that will be used to test new electric vehicle-focused products in the areas of thermal and battery management. University of Toronto will also use this vehicle as part of a joint battery research project.

“Today, everything is controlled by software, which is protected and would require source code and modification in order to do the kind of adaptation that we need,” says John Antchak, vice-president of Litens Automotive, who is related to the Antchaks who own and operate Northwest Sheet Metal but is not affiliated with the company. “With this project, we started with an open source vehicle controller and built out from that. Everything in the vehicle is controlled by it, including the interior functions, lighting, steering, and others.”

The ultimate goal was a modern, first-class OE level electric powertrain, and the results have been outstanding. The ET187 is an all-electric truck built in house by the Litens’ engineering team. The prototype will start off as a new Ford Ranger 4x4 minus the standard powertrain and associated life support systems, which will be replaced by the electric system.

The heart of ET187 is a fully engineered low center of gravity lithium-ion battery system delivering 80 KWh capacity mounted under the floor between the frame rails. Muscle is provided by two 3 phase AC PM motors in series taking in 400V through two inverters and delivering 840 Nm of torque to a single gear reducer and out to the original transfer case and rear axle system.

Keeping the simple and effective driveline was one of the developer’s targets and ultimately resulted in the unique and innovative battery case design that accommodates the propeller shaft running through it.

Northwest Sheet Metal fabricated the battery case, battery management housing, and vehicle mounting system for the prototype. Four six-foot-long Tesla battery modules were extracted from a Tesla underfloor battery case and re-engineered to fit under the floor of the Ranger with the driveshaft for the rear wheels running down the center. Together, the batteries weigh 1,000 pounds.

“The battery case is complex with many precise dimensions to properly support the batteries and to fit into a very tight package between frame rails, rear axle, and transfer case,” Antchak says. “This required hard adherence to tolerances and precise craftsmanship.”

Considering road loads (bumps), cornering, potential impact, and stress from acceleration and braking, the battery system is under tremendous stress, which means it had to be fully validated through extensive computer modelling and simulation.

“The welding and forming have to be professional level to match the strength predicted by the computer models,” Antchak says. “The design and fabrication of this system was the hardest part of the truck project.”

Gord Gohringer, shop superintendent at Northwest Sheet Metal and Local 280 member, says because the project was a brand new idea, Litens essentially gave the team at Northwest a series of concept drawings that the team had to rework and confirm with the client.

“They weren’t exact, so we couldn’t just download them and begin fabrication,” Gohringer says. “We had to redraw the part and put it into the system to see if it would work. They knew the size and what they wanted, and we had to make it happen.”

The prototype’s uniqueness and the fact that it had zero tolerances presented a challenge for the team. “In CAD, the drawings are given sizes and allowances,” Gohringer said. “There was none of that. We had to make sure that the samples would work. It required special tooling, and eventually we had to create a bunch of samples to make sure we could even make it with zero tolerance.”

Having a cohesive, skilled labor and management team is what makes it possible to complete this kind of one-off, completely outside of the wheelhouse job, Gohringer says. It is what allows contractors to pivot on a dime.

“Because we are working in a union environment and trained by the union, we have the skilled workforce and management to adapt on the fly,” he says. “Without that kind of team, we couldn’t even begin to tackle something like this.”

Another factor is Northwest Sheet Metal’s readiness to adopt new technologies, making it one of the province’s most advanced in that capacity.

For starters, the company has a 20-foot laser metal cutting table, complete with fully automatic 4 coil line feed, capable of cutting 1-inch thick steel with absolute precision. It runs a Full Iowa Precision 5-foot coil line, a Vulcan Waterjet Table, which provides a green initiative by reducing waste by over 80%, a 20-foot Vulcan plasma table, and several other state of the art innovations.

“Northwest has invested in itself heavily with CNC technology that opens doors that were never available before,” says Bernie Antchak, co-owner and business operations manager for Northwest Sheet Metal. “We believe in it so much that we are looking to expand our detailing department even further.”

Northwest uses BIM and detailing on almost every project, and in fact, gets hired by other contractors to perform this task, as well.

“We have all the latest in software and drawing programs and the talent here to use it all to its highest potential,” Gohringer says. “The more doors we can open with technology that gets us moving out of the same old routine, the more work and opportunity we can offer our union members.”

“It also helps to be connected to two guys who are not afraid to tackle tough jobs,” John Antchak says. “Many vendors were afraid to tackle this job due to tolerances and quality expectations.”

At the time of writing, the project had run eight months through the COVID period and involved the collaboration of over 60 people in different disciplines working on subsystem teams: battery, powertrain, chassis, and design. The result is a testament to the talent, commitment, and adaptability of this immense team and a nod to the future. ▪

Jessica Kirby is a freelance editor and writer covering construction, architecture, mining, travel, and sustainable living for myriad publications across Canada and the United States.