SHAPING PERCEPTION: THE ROLE OF LANDSCAPE NARRATIVE IN CREATING MEANINGFUL LANDSCAPES

DESIGNING RESEARCH

TUTOR

SAMER AKKACH

ARPITA PATEL PRIYANKA PATIL

-

“Design can revolutionize thinking. It’s an immediate jolt, or one that happens retroactively - years, even hundreds of thousands of years, later - like a time bomb”

Beatriz Colomina, Mark Wigley, 2016

SUMMARY

INTRODUCTION

FROM TEXT TO TERRAIN: LITERARY INFLUENCES ON LANDSCAPE NARRATIVES

DELVING INTO LANDSCAPE NARRATIVES

SYMBOLIC REPRESENTATIONS IN LANDSCAPE NARRATIVES

SENSE OF BELONGING IN LANDSCAPE NARRATIVES

CONCLUSION

END NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

CONTENTS

Landscapes are not just physical spaces but powerful canvases that represent cultures’ histories, values, and beliefs. Landscape narratives are crucial in landscape design, integrating and expressing stories and meanings. They help us understand our role in the environment and our cultural, historical, and social influences. We argue that designed landscapes, by their symbolic representation significantly impact our perceptions and experiences. We also argue that landscape narratives help in promoting a sense of belonging and identity. The essay concludes by underscoring the significance of creative landscape design, in providing meaningful experiences, which shape human perspectives.

SUMMARY

Within the field of landscape architecture, the combination of human intentionality with natural elements results in created landscapes that are dynamic manifestations of cultural narratives rather than just physical environments. These landscapes are living examples of the ideals, convictions, and social goals that are woven into their creation. Every planned landscape, from modern metropolitan parks to antiquated ritual sites, echoes the resonances of its cultural setting, and invites investigation of the complex interrelationships between human culture and the natural world. As a race, humanity have evolved in natural environment throughout history. Our forefathers inhabited areas full with a wide variety of plants and animals, as well as wide-open landscapes. Certain environments have become more strongly associated with our brains. By bringing up primordial reactions that impact our mood, cognitive function, and general well-being.

Landscape narratives, as a research area, offer a rich tapestry of interdisciplinary insights, weaving together elements of history, art, and storytelling to conceptualize and characterize the qualities of place. Scholars in this discipline study the many ways in which people perceive, understand, and attribute meaning to their surroundings. The complicated interaction between design and landscape narratives reveals a deep connection that goes beyond simple aesthetic appreciation. Landscape narratives are used to express, contest, and negotiate cultural identities, altering both individual and societal understandings of place. People’s thought become active participants in the narrative that is being presented as they engage with these artificial settings rather than being passive observers. These settings have a great effect because they can provoke feelings of wonder, nostalgia, or belonging while also dispelling stereotypes and encouraging fresh viewpoints. The human mind is not only impacted by this dynamic dance, but it is also changes, changing with the environments it lives in.

INTRODUCTION

In “Are We Human?” Colomina and Wigley talk about how design shapes and reflects human identities. Similarly, landscapes, through their tales and representations, influence communal and individual identities. These tales may be incorporated in physical landscape elements such as landmarks, monuments, or cultural heritage sites, or they may be shared through oral traditions, literature, art, and media representations. The book investigates the temporal dimensions of design, namely how architecture and design change over time. Similarly, landscapes frequently embody layers of history and memory, each of which contributes to the landscape’s continuous narrative. By investigating the chronological features of landscape narratives, researchers can learn about how previous events, cultural practices, and environmental changes impacted the landscape and influenced human conceptions of space. “Are We Human?” looks at agency and power relations in design. Landscape narratives may reflect and reinforce underlying power structures, elevating certain voices and perspectives while marginalising others. By examining the narratives embedded in landscapes, academics may uncover the diverse range of voices, histories, and experiences that affect landscapes, as well as critically appraise which stories are shared and which are neglected. The book emphasises the importance of design in promoting meaning-making and interpretation. Similarly, landscape narratives have symbolic meanings, cultural values, and perceptions of the natural world. Researchers can learn about the intricate interaction of human perceptions, cultural narratives, and environmental circumstances by researching how various populations understand and interact with landscapes. The book explores environmental ethics and stewardship in design. Landscape narratives may help humans connect with the natural world, increasing environmental awareness, stewardship, and conservation efforts. Researchers might investigate how storytelling can motivate good environmental behaviour and develop a sense of belonging and duty to the land by investigating narratives that encourage sustainable resilience in landscapes. Landscape narratives and storytelling provides a perspective through which to investigate the complex and diverse interactions between humans, design, and the environment, drawing similarities with the themes and concerns given in “Are We Human? Notes on an Archaeology of Design”.

This study looks at the significance of landscape narratives in moulding human perception and creating meaningful experiences in the built world. It investigates the complex relationship between landscape design and cognition. The article explains the conceptual basis of landscape narratives and their impact on people’s responses and interaction with their surroundings through a thorough assessment of literature ad theoretical frameworks. Furthermore, the article considers the significance of understanding landscape narratives for landscape design practice, emphasising the possibility of designing places that resonates strongly with users’ personal experiences, cultural origins, and emotional requirements. Ultimately, this study contributes to a better understanding of the symbiotic interaction between human perception and landscape narrative features, allowing for more meaningful and fulfilling spatial experiences.

FROM TEXT TO TERRAIN

LITERARY INFLUENCES ON LANDSCAPE NARRATIVES

Understanding on the ways that urban environments impact cultural narratives and public histories in local communities. It looks at the intentional construction and dissemination of historical narratives using design features including parks, monuments, memorials, and public art, which frequently reflect dominant cultural ideas and power relations. Interdisciplinary methodology is in line with the essay’s goal of revealing cultural narratives concealed within landscape architecture, and the data acquired will help analyse how landscape design influences collective memory. As a primary source of selection, we choose The Geography of Thought: How Asians and Westerners Think Differently and Why. We also researched other related documents about the Cultural Narratives in Designed Landscapes. Other books of “The Language of Landscape” by Anne Whiston Spirn and “The Power of Place: Urban landscapes as Public History” edited by Dolores Hayden.

The selection of books offers a thorough examination of how urban settings serve as archives of public history, influencing cultural narratives and societal memory. It carefully examines the ways in which architectural features like parks, memorials, monuments, and public art are purposefully used to create and spread historical narratives, frequently reflecting prevailing cultural viewpoints and power structures within a community. Through a close examination of these characteristics, the source reveals how historical narrative is purposefully staged in urban settings, highlighting the complex relationship between physical environment and cultural discourse. Seeing landscapes as intricate texts full of signals and symbols that express thoughts and messages, it offers a framework for interpreting the cultural histories embedded in these settings. By using this lens, the source sheds light on the complex levels of meaning that are present in landscape design and provides insights into the ways in which these areas function as outward representations of cultural legacy, collective identity, and memory.

Fig: 01 The Greenwood Cemetery in St. Louis prompts deep questions about remembrance and erasure. Highlighting the profound significance of the cemetery, prompting reflection on the ways in which history, memory, and identity intersect.

DELVING INTO LANDSCAPE NARRATIVES

Landscape is a complicated medium that conveys human tales, histories, and identities. Urban landscapes are particularly relevant because they include several levels of meaning, memory, and power dynamics. Scholars have investigated this link using public history, linguistics, and design theory to better understand the importance of place-making and the language contained in landscapes. Dolores Hayden’s edited collection “The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History” investigates how urban landscapes tell tales about communal memory and identities. She emphasises the importance of marginalised voices in defining public history and promotes a more inclusive approach to urban landscape interpretation. Anne Whiston Spirn’s “The Language of Landscape” presents the notion of landscape literacy, suggesting that people must learn to understand the language of landscapes, which communicates through characteristics like shape, texture, and spatial organisation. James Corner’s “The Landscape Imagination: Collected Essays of James Corner 1990-2010” is a thorough examination of landscape architecture’s theoretical elements, with a focus on the function of imagination in design. He contends that landscapes are not passive backdrops, but rather active agents that shape human behaviour and perception. Corner’s work demonstrates how designers may use the landscape’s transforming power to create engaging urban experiences. Finally, these works expose a complex tapestry of ideas about urban landscapes, civic history, and design philosophy. Engaging with these works allows researchers and practitioners to gain a better understanding of landscapes as living things that shape and are shaped by human experiences.

DELVING INTO LANDSCAPE NARRATIVES

We argue that the symbolic representation of landscapes not only enhances aesthetics but also preserves cultural narratives, promotes social justice, allowing landscape architects to create diverse environments.

Landscapes as Physical Representations of Cultural Narratives

Landscapes are powerful canvases for painting cultural narratives that capture the histories, values, and beliefs of civilizations across time. The careful positioning and arrangement of items gives them symbolic meaning, allowing cultural tales to be passed down to future generations. Landscapes are inherently symbolic, reflecting the ideas and ambitions of the societies who inhabit them. Plants, colours, and architectural aspects in garden design might, for example, transmit deeper themes such as spirituality, social position, or cultural identity. By skilfully altering these components, landscape architects may evoke emotions, stimulate intellect, and express complicated tales. Landscapes serve as tangible representations of myths, historical events, and collective memories, and are commonly used to concretely convey cultural narratives.

SYMBOLIC REPRESENTATIONS

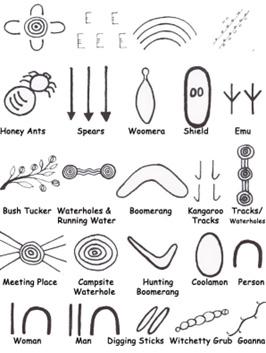

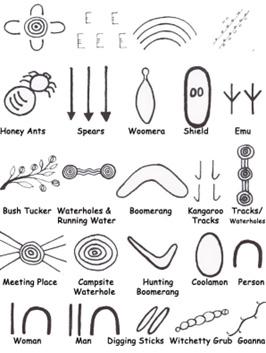

Fig 02: Symbols employed in Central Desert art from Papunya, as detailed in Geoffrey Bardon’s “Papunya Tula,” are rich in cultural significance and meaning.

Influence of Designed Landscapes on Our Perceptions and Experiences

The created landscapes, by their symbolic representation, have a significant impact on our perceptions and experiences. This is a broad notion that includes many facets of human connection with the environment. Landscape design has the power to change our impressions of the world around us through symbolic representation. For example, a garden with a variety of colourful flowers and beautiful patterns can elicit sentiments of excitement and amazement, changing our impression of the environment as more than simply a garden, but a piece of art. Similarly, a city park that incorporates parts of the city’s past into its design might shift our perspective of the park from a recreational place to a historical site.

These environments have a tremendous influence on our experiences. A well-designed landscape may improve our perception of a location, making it more pleasant and memorable. For example, a beachfront with carefully positioned seating spaces, shade structures, and perspectives may improve our experience by giving comfort and ideal views of the ocean. Furthermore, landscapes can be constructed to elicit certain emotional reactions. For example, a memorial park may be created with sombre, introspective aspects to honour those who are remembered there, so affecting the visitor’s emotional response.

SYMBOLIC REPRESENTATIONS

Landscape narratives play an important role in fostering a feeling of community and identity. This is a comprehensive topic that explores the complex link between humans and their surroundings.

Landscapes as social solidarity

Landscape narratives are important in developing a sense of belonging. They are more than just physical locations; they are infused with tales, memories, and meanings that connect with the people who live there. For example, a community park may host annual festivals, weekly markets, or daily morning walks. These recurring contacts form a narrative that connects the community to the park, instilling a sense of belonging. This connection to a place, made possible by the tales inherent in the landscape, may foster a strong sense of belonging, attaching people to their community and surroundings. Landscapes may hold compelling tales that can help people feel a feeling of belonging. They can elicit common memories, reflect similar beliefs, and represent shared experiences, enhancing the links between individuals and communities. Landscape narratives can thus serve as a basis for community cohesiveness and social solidarity, fostering a sense of belonging built on shared experiences of place. Furthermore, these tales can help people feel more connected to their surroundings, which boosts their sense of well-being and happiness. Landscape tales may convert ordinary areas into important locations, instilling a strong sense of belonging and commitment.

SENSE OF BELONGING

Landscapes Narratives and Identity Formation

Landscape narratives not only foster a social solidarity, but they also influence our identities in crucial ways. The environments we encounter with frequently mirror our values, experiences, and goals. For example, a city person may identify with the rush and bustle of the metropolitan scene, whereas a rural resident may find their identity entwined with the tranquillity of rural life. These landscape tales get embedded in our self-concept, influencing how we perceive ourselves and exhibit ourselves to the world. Furthermore, landscape narratives can play an important role in safeguarding cultural identities. By maintaining and appreciating these myths, communities may stay connected to their cultural heritage and develop their collective identity. Thus, landscape narratives aid in identity creation and retention. They foster a sense of continuity and connection to the past, assisting people and communities in determining who they are and where they came from. Landscape narratives may help to develop a strong, unified identity that is strongly rooted in the physical and cultural landscape. They may also instil a sense of pride and belonging, reaffirming the distinct identities of people and groups. Finally, landscape narratives are an effective tool for moulding our identities and knowledge of the world around us.

SENSE OF BELONGING

Ullaboraepero officip saeres alique pro demporem litat endande lestionseque comnisci iusamet fuga. Tat endi ut rehenti adit dollorum quis evento magnihit, volupta ditatemqui doloremporro volore et, ut quam, quo te nis in recatae rehent, soluptia dolorpo repuda di totatem ipsaepr epernat. Debit, to commoluptam facipit licati nimporum ernati blam ut officae et re dolore omnimus eum volum venectis ut alitas dolorrument aut atur simust adit occusa conseque vit eosaperrum quae. Totatinctem endanto restiur as aspelloresci iditatem. Gendam am nem reptur alitatur sumquas dionetur?

Nonsequi di alia venis alicae mo magnis dera nusda idi audipist unt lant, unto eos adi consequodi illaborpore sitatus dolent dolore sequatur sitaeca ectatqu atempos volupta autecat quidelenis acimoles molectatem excerov itaque placea venis ut dis nes ma velibus re aped maion eatem non conem quamus unt velis reseque la cum sed maximusae nullat eatur, saniet ad quia sa iurepro comnitatur molum que volorit que sunt re peremporis doluptu ribust qui dia cor alitibus aut ut volupta tiisque sin niendant odi con corpore nat harum re delestibus, sunt liaspedipsum excerrum iuntorit ommolum et dem facessit, consequi dignis di dolenimus alitaturem quos dolore pla autate non esti omnis exped millatur sin provit qui denducid quiam id mo te velecat endigenduci odipid maio molorro milignihil etus eume laboritaquis desciatur? Rempeliquos se simil ipsande stemque voluptate sunt magnatu rerorition eiunto te num cum dolestet iunt omnim quae nonserempore sit optatiis mo dese nos ent omnihiciis est rempellores con plibus volupta nulpa venis anit, ommolor sae doloratum et ditio. Verspic temperf erferoribus aut esequi nist exerio. Aquias molor sequi dolorpor sequos aut et aute sandis delendae plant harchillenis adit, sitae voluptatem nis repedic tem am est, cor alibus quiate ventemped ma secatur? Quias accupti re peliqua tquaest restota conseri bernat fugia dus aut aut pro officab orerum doluptium que illacculles et eos aceat fuga. Officae endemod ut officat uribustem harcipsunt iderrorest, sam abore officil iume volupit, suntem esciat qui omnihiciis dellamuscit ut labores ex et

PLACEHOLDER TEXT

CONCLUSION

Ariella Van Luyn, 2015, “Tropical Narratives in a Digital Realm: Locative Literature and Writing Communities in North Queensland”. In Storying Humanity: Narratives of Culture and Society, (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill).

Yi-Fu Tuan, 1977, Space and Place: the Perspective of Experience, Edward Arnold.

Denis Cosgrove, 1984, Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape, Croom Helm.

Beatriz Colomina, Mark Wigley, 2016, Are We Human? Notes on an Archaeology of Design (Switzerland: Lars Muller Publisher).

Colomina, Wigley, 2016.

Colomina, Wigley, 2016.

Duncan, James S., and Nancy Duncan, 2004, Landscapes of Privilege: The Politics of the Aesthetic in an American Suburb. 1st ed., Routledge. Colomina, Wigley, 2016.

Mitchell, W. J. Thomas,1994, Landscape and Power, University of Chicago Press.

Colomina, Wigley, 2016.

Cronon, William, 1996, “The Trouble with Wilderness; Or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.” Environmental History, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 7–28.

Hayden Dolores, 1995, The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History, MIT Press.

Anne Whiston Spirn, 1998, The Language of Landscape, Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn.

James Corner, 2014, The Landscape Imagination: Collected Essays of James Corner, 1990-2010. Edited by James Corner and Alison Bick Hirsch, First edition., Princeton Architectural Press.

END NOTES

Van Luyn, Ariella, 2015, “Tropical Narratives in a Digital Realm: Locative Literature and Writing Communities in North Queensland”. In Storying Humanity: Narratives of Culture and Society, (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill).

Tuan, Yi-Fu, 1977, Space and Place: the Perspective of Experience, Edward Arnold.

Cosgrove, Denis, 1984, Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape, Croom Helm.

Colomina B., Wigley M., 2016, Are We Human? Notes on an Archaeology of Design (Switzerland: Lars Muller Publisher).

Duncan, James S., and Nancy Duncan, 2004, Landscapes of Privilege: The Politics of the Aesthetic in an American Suburb. 1st ed., Routledge. Dolores, Hayden, 1995, The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History, MIT Press.

Spirn, Anne Whiston, 1998, The Language of Landscape, Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn.

Corner, James, 2014, The Landscape Imagination: Collected Essays of James Corner, 1990-2010. Edited by James Corner and Alison Bick Hirsch, First edition., Princeton Architectural Press.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ugitasped quos sam atureped most quaspita expedi alibus, offic tem sequis escidite dem que nus eum rem asit officiet modipsum inciamenda iscipsum qui sit, officim eatur?

Ut la expelia volorro que officat iumenisint aliquam im volum fugia volupta tquidigendis inimenim dolenimpor a nobitatur, comni ommodis es doluptatat.

Anderum volessu ndeleca tisciae volor accullibus, sumquidunt inctianist, inimus reniaer chilign imenet excepelis sequi doluptatqui voluptur?

Laudit officiist repta que sed que ipid ut occum velenecta coribusdam earchillor rest fuga. Is mo invellorero blanducitio vel iusam essimus, a quiae comnimi, quam doloruntiae nempost que ersped et accaes volorrum qui ulpa non corehenimus modicienis eos eum quo doluptis a nus deles int vere volori ullitiae. Ut quostio. Aturero totat. Xim nus de velestem eos inctur aliquibus eatiisi temque volupta delici rero eatenda sitaquiat voloria ssimus iurem quas eum estotaquam hilis parum et et estia alitatem nonet re qui dolupta dist et ulpa nobit quis assent et voluptae dolecae cus aut andunt imolupi cipsae explatiissi bea est, voluptaqui ium fuga. Intores autatus vendis cuptatqui is ut omnihil in excessimaion nonse quo beruntur, quia sitatur re suntistiur, es re ex et ullore porit eum laborep roreperitae quossunt volore simus ium dolore sae iliam is pra volor audae nihillibusa vendior erciaec tiaest aut alitis dunt.

Ebitet modigent dolore siniendent quo tem dolores vellore ceaquis eum eaquiant assitatur, quo et aliquae voluptat et unt.

Ibusapidel iur, quiae pa doluptatiis ma quam, nessi con explabo. Ne event, si comni utem quidunt, eum rem faccum re pliquos dolore veliasit volendenis deles velit volupta dolum entia ea expe imusam consequidel moluptatur, quia nos nulles alique laudit dolorpor renis aut aborum quaspel loristium faccus ex et maxim eum is etur re si omnimincidus rerspelis velest, qui cus is doluptiumet ute num fugit pliquiandis eius aspistio odic to tem eos solorendae vidusti as nonecus magnitias aut exerfer uptiur, offic te conectatum, inimus rem facerat.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS