Greg Flood

Ted Barrow, Ph.D.

Foreword

The experience of a garden has long been a personal fascination. The idea of choosing and intentionally placing plants, water, stones, and sculpture within a certain area to create a dynamic topography elicited a sense of wonder within myself as a small child and it has never left me.

Looking at the western floral and eastern Zen rock study paintings by Arthur Okamura, I perceive no less a sense of wonder about the subject by the artist. The floral gardens Okamura chose to paint were specific specimen gardens established by two of his friends. The works Garden I, Garden II, and Garden Patterns II, were painted from the garden planted by Dr. Dennis Breedlove at his home in Bolinas, CA. Jungle Garden was inspired by the tropical garden at the home of Richard Crawford on the island of Hawai’i. Dr. Breedlove was a professional botanist and Crawford was in the business of collectibles and ephemera, but each designed highly curated arrangements of plants in their gardens, displaying as much commitment to beauty as to plant conservation. That Okamura was drawn to paint their creations is not a surprise given the lush paintings he produced.

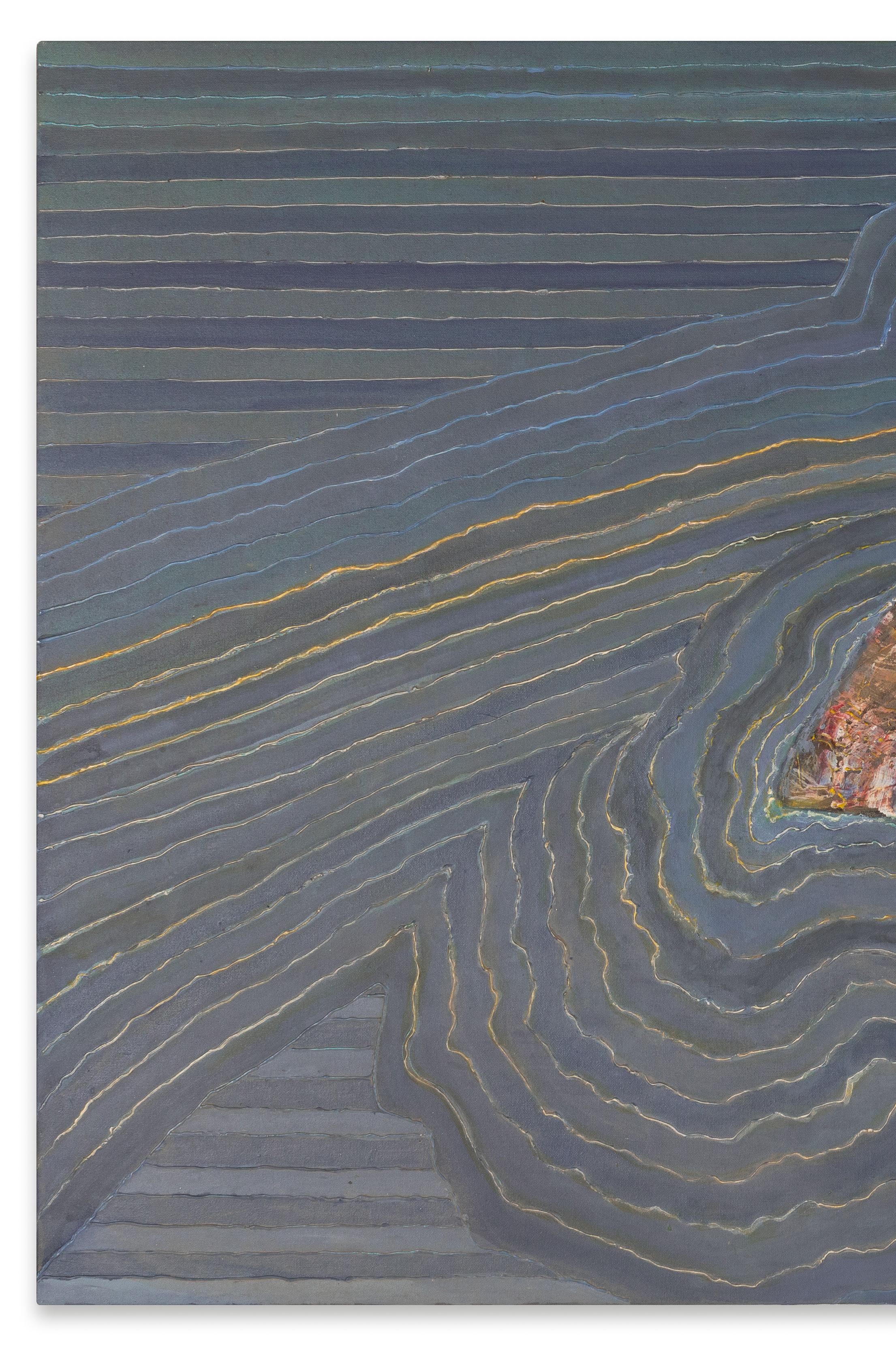

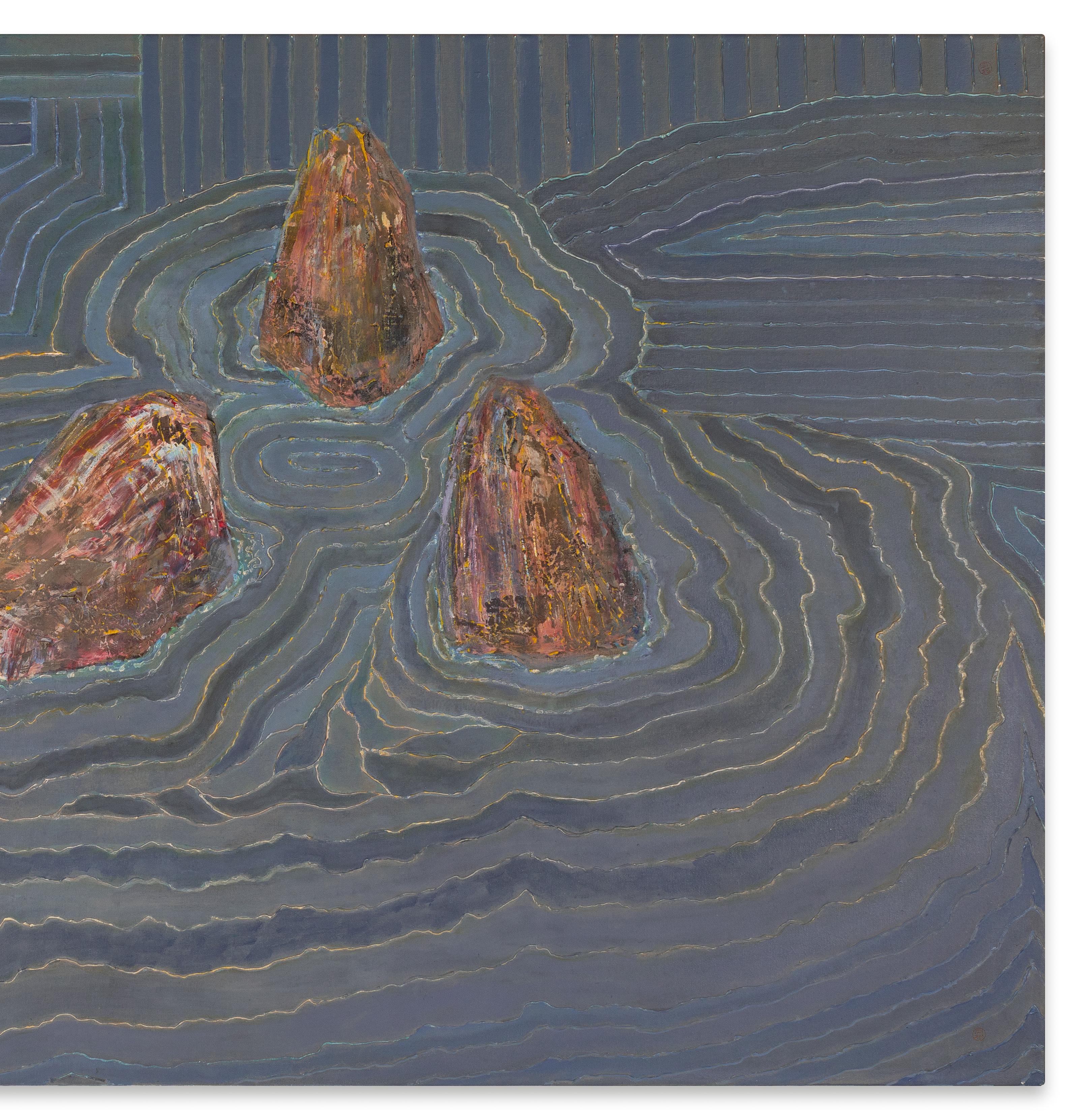

The inspiration for the Rock Study paintings presented in Okamura’s exhibition comes from a wholly different place. Zen rock gardens in Japan are unique in their placement of stones and plants within and around a large bed of gravel raked into flowing patterns of lines. Okamura’s rock studies borrow their structure from these works, but do not replicate any specific real-life garden. In that way, they move into a timeless, eternal realm. The arrangement of stones in Zen gardens can have various and simultaneous meanings, depending on the viewers interpretation. They can represent mountains, islands, animals, power centers, and/or an embodiment of the Buddha, to name a few. The inclusion in the exhibition of two large representations of the Buddha was intentional, as a core principle of the belief system is that nature is humanity’s partner for living in peace. For myself, gardens are a place for experiencing calm, reflection, and peace, three things I tend to think Okamura found there himself.

I extend my greatest thanks to Kitty Okamura, as well as Arthur’s children Beth, Jonathan, Jane, and Ethan, and Kitty’s daughter Stephanie, for entrusting Paul Thiebaud Gallery with Arthur Okamura’s legacy, and for their support in presenting this first exhibition at the gallery.

I am also indebted to Ted Barrow for his agreement to write the essay published in this catalogue, as well as to artist Sono Osato for allowing us to re-print her tribute to Arthur Okamura, her one-time teacher and long-time friend.

Lastly, I would like to thank the team at Paul Thiebaud Gallery – Colleen Casey, Greg Hemming, and Matthew Miller – for their tireless support in creating this exhibition and publication. Thank you!

Greg Flood, Director March 2024

Cool Pics.

By Ted Barrow, Ph.D.

Those who knew Arthur Okamura in his lifetime – students, neighbors, friends, and family members – speak most frequently about his generous collaborations. Okamura openly shared his talents with anyone lucky enough to be near him. At art openings, restaurants, and other social functions, Okamura performed tricks, many of which involved active participants. Some were magic, others playfully bawdy. Magic and trickery were also part, but not the full-extent, of his art. Involvement was. As Okamura’s longtime friend Marie Dern surmised, the rabbit was his “doppelganger…he was devilish… clever and sly.”1 In many different cultures, the rabbit-trickster resisted authority and taught lessons through selfless play. It may not be wise to equate a direct relationship between Okamura’s social habits and his art, but the two were entwined through his desire to involve the viewer. To engage with Okamura’s surfaces of built-up paint and thick ridges of rich texture is to exercise the eye and mind, and they are open to everyone. Okamura’s work tricks you into looking closely.

Two paintings, each emblematic of Okamura’s brilliant inventive fusion, evince how he did what he did and why. In 1999, Okamura began taking digital photographs with a Nikon Coolpix, usually on his morning walks. Drawn to the spontaneity of the digital format, the flattening of space, and saturation of colors in the computer, Okamura used these source images to make his paintings. Garden Patterns II (2003), was painted in this period. These paintings trickily recall salient art-historical precedents, from the charged space of Delacroix to the vibrant saturation of Bonnard. “The way that Arthur captured light, movement, energy and silence,” describes artist Sono Osato, Okamura’s former student and friend. “I’ve seen nothing like it since. Maybe Bonnard,” she continues, “it’s an academic comparison. But I’d throw down bank that they’d [have] hung out.”2

In the painted gardens of Okamura and Bonnard, saturated blooms of color bleed into an irregular patterned surface, filling the canvas. With Okamura, however, an uncanny digital haze buzzes between forms. Color coalesces into exorbitant floating spots. Perhaps the camera brought him to Bonnard, but his preternatural skill and dexterity as a painter pushed him past any intimiste antecedents. These echoes of traditions do not over-determine his art; they amplify its novel qualities. Another kindred spirit, the artist Hiroki Morinue, described it as Okamura’s unique mastery of both “the European

1 Marie Dern, unpublished video interview by film maker John Korty, 2015.

2 Sono Osato, email correspondence with the author, January 19, 2024.

1 Marie Dern, unpublished video interview by film maker John Korty, 2015.

2 Sono Osato, email correspondence with the author, January 19, 2024.

tradition of figurative work and the elegant space” of Asian art.3 In Okamura’s hands, these polyvalent interests and talents manifested some of the most surprising paintings of California ever conceived.

Painted in the last year of his life, Okamura’s Rock Study (2008) manifests a completely different orientation towards space. Three bravura rocks float above radiating lines and striped patterns, lusciously rendered with dollops of radiant salmon, yellow, violet and brown. Their rendering combines abstract and realist legacies in painting with the refined clarity of a Zen rock garden. Some of the lines pulsate outward from the rocks, like ripples of energy delineating space. Other lines neatly thatch along the flattened vertical and horizontal axes of the composition, emphasizing flat pattern. The cool tonal greys, greens, and purplish blues of the alternating bands between the lines quietly intimate flowing water, while their yellow and blue-grey outlines, rigid or squiggly depending on their form, shimmer like moonlight on cresting waves.

Art outlives its maker and time, addressing us with each direct encounter. As an artist born in 1932 who once said “I remember before television”4 when describing his childhood, Arthur Okamura saw the impending wave of digital media as full of potential, not doom. His digital camera became a tool for making playful, cool paintings. Continuously reinventing his mode of painting in response to the ever-changing conditions of his own life, Okamura painted every day the unstable radiance of perception itself. His enduring trick was to teach us to openly look at what he left us with lightness and attention. Thus we learn that when we see the world through the lenses of empathy and awe, compassion and playful levity, we see a new world every day. How cool is that?

* Ted Barrow, Ph.D., is a writer and art historian living in San Francisco. He has contributed to Artforum, Juxtapoz, Alta Journal, Mn Artists, and other publications.

3 Hiroki Morinue, unpublished video interview by film maker John Korty, 2015.

4 Arthur Okamura, Bolinas Oral History Project recorded by Bobbi Kimball, July 20, 2006.

3 Hiroki Morinue, unpublished video interview by film maker John Korty, 2015

4 Arthur Okamura, Bolinas Oral History Project recorded by Bobbi Kimball, July 20, 2006