STR YA design adventure food wilderness 01.4

As the landscape turns golden and the trees go ablaze with color in their familiar rhythm—cottonwoods, aspens, larch—the giddy energy of summer settles into the calm and ease of fall.

This is the second autumn for the green o, and if there’s one thing the past year has reaffirmed for all of us here, it’s that for all this place has to offer on its own—the high-design Hauses, the innovative cuisine, the natural beauty that envelops the property—it’s the people who are the true lifeblood of it all. The inventive spirit of our chefs elevates Social Haus to a bona fide culinary destination. The infectious love of the wild shared by our activity guides is what makes an afternoon of wrangling cattle or casting for trout into a lifelong memory. Every aspect of the green o experience is taken to new heights by the warmth, passion and generous spirit of our team members.

Is there anything better than autumn in Montana?

Photo credits: (cover and spread) Stuart Thurlkill

With that revelation, it felt only right to dedicate much of this issue of Stray to celebrating makers and visionaries whose big dreams and zest for creation have helped them bring fresh energy to their respective fields. Ahead, you’ll meet a collector who turned her twin passions for art and wine into a vineyard- cum -sculpture park, an outdoorsman who is introducing a new generation of BIPOC adventurers to the wilderness, a husband-and-wife team whose obsession with artisan-made knives has inspired entrepreneurs across the country and even one of the green o’s very own, a painter on the construction team who moonlights as a skilled norteña singer.

Amidst all that, we’ll celebrate autumn with stories that delve into the beauty of a coastal enclave in fall, the allure of flyfishing on the Blackfoot after the heat of August has faded and one Montana poet’s bittersweet meditation on the cycles of nature and life. Time to grab a sweater, pull up a chair and relish the start of a new season. We can’t wait to see what it holds.

Jeff Severini Manager the green o

Jeff Severini Manager the green o

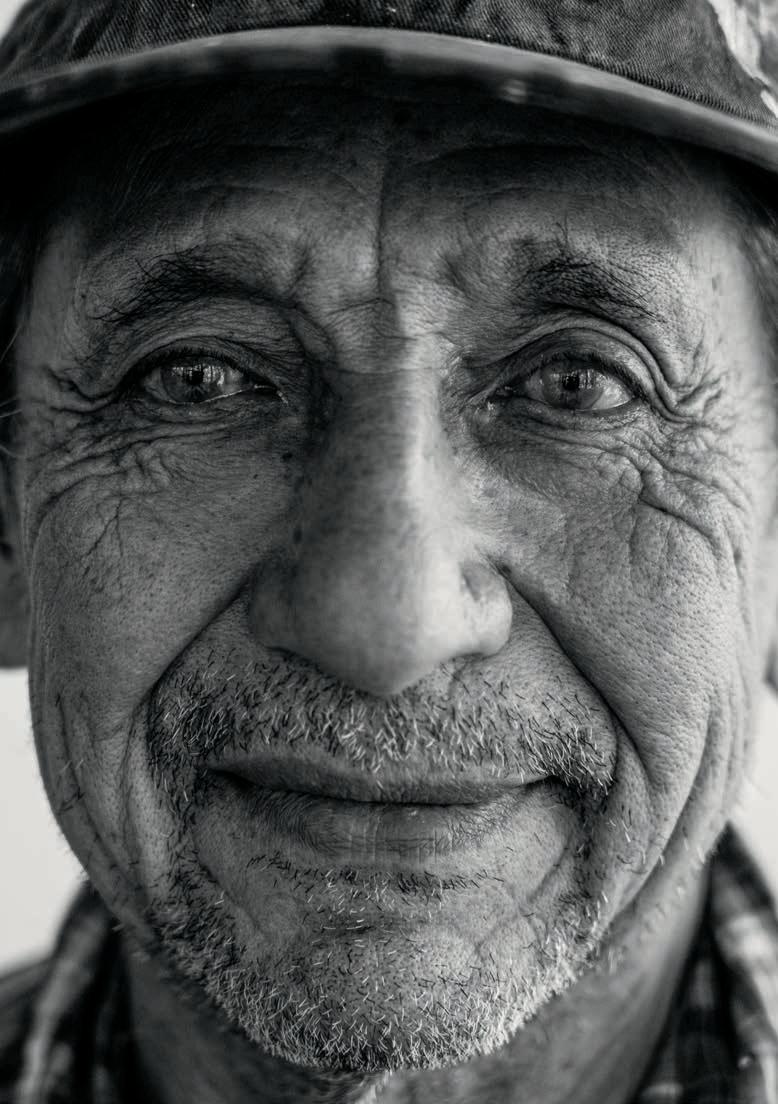

A question I get a lot is when’s a good time to come to Montana to fish? End of June or early July is a safe bet, and I also love the fall. Come September it starts to cool down on the Blackfoot. You see the leaves changing, the elk and deer are moving around a bit more, and there’s mist on the river before the sun comes up. You get there early and watch it start to lift up. Oxygen levels in the water go up, and the fish are a little bit happier. That time of year you can catch cutthroat, rainbows, brown trout—the brown trout become more active, so you can transition into streamer fishing, which gives you the opportunity to catch some of those 20-plus-inch bigger fish.

Trout eat bugs most of the time, but with cooler temperatures they become more predatory toward minnows and baitfish. A streamer fly is subsurface—it could have duck or marabou feathers, and it’s got a lot of movement, a lot of color. It acts like a little trout or a sculpin minnow under the surface. Streamers are typically heavy, and a little more difficult to cast. You’re trying to hit a log jam, get that fly in the perfect spot and retrieve it back. So you’re very active, you’re standing up. It’s a lot of fun. You’ll see the fish come out and flash on it. It doesn’t happen every cast, but when it does, it’s exciting.

I try to tell the guides it’s not necessarily about how many fish you’re catching—it’s about that whole experience. You get kind of locked in on what you’re doing, but it’s nice sometimes to take a minute to enjoy the scenery and be like, how cool is this?

Photo credits: (left and upper right) Stuart Thurlkill

By Lila Harron Battis

Photo credit: Stuart Thurlkill

Photo credit: Stuart Thurlkill

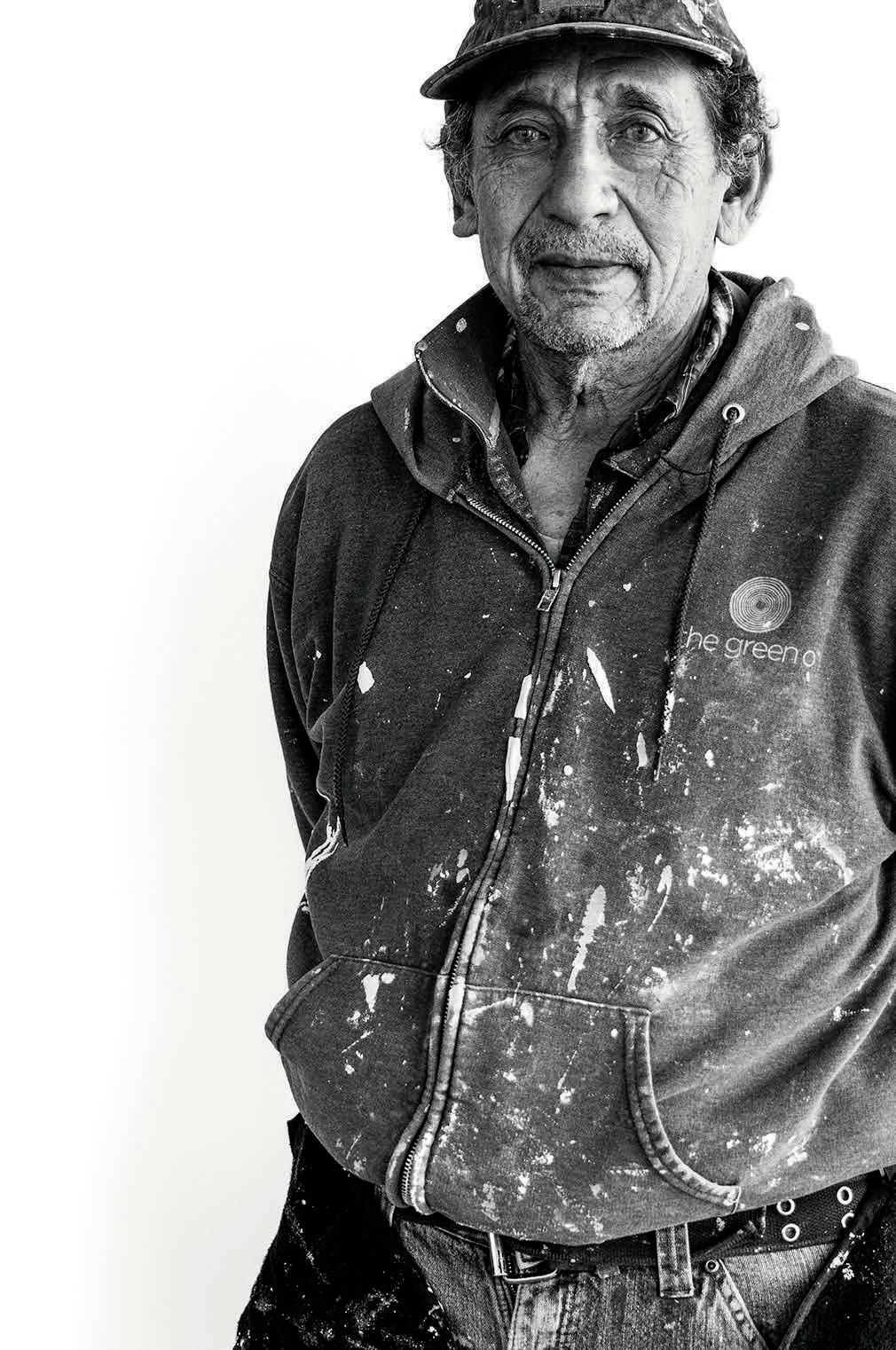

If you’d happened upon the green o long before it opened, when the pathways were still streaked with clay and hammering echoed through the trees, you might have spotted a man in plaid, his stubble more salt than pepper, his face bearing the creases of someone who’s spent much of his life smiling. He was likely wielding a paintbrush. This is Victor Duque, a 10-year veteran of the Paws Up team. “I often work on spaces where people stay, and I love that guests love my work,” he says. But Duque’s skill and long tenure with Paws Up belies his true passion. “I enjoy painting, and I always try to do the best I can and make it good quality,” he says. “But when I’m in front of an audience, with a microphone in my hand, singing? That transforms me. It transports me— spiritually, emotionally, energetically.”

The son of a French-born father and a Spanish mother, Duque grew up on a family ranch in Guerrero, Mexico, singing norteña and cumbia music with his dad. That childhood ritual evolved into a true talent, and Duque chased his dream to Acapulco, where he landed a radio show, founded a musical group and settled into the trappings of adulthood. Album promotion took Duque and his family to California in the late 1970s, where he nabbed a job performing and working as an announcer on KNSE, colloquially known as Radio Quince, a top Spanish-language station. He took side gigs as a painter to help support his young family. “I always worked both at the same time—painting during the day, and at night, singing or presenting or doing a show for an hour or two on the weekends,” he explains.

These days, Duque’s work at Paws Up—and his monthly trips to see his adult children and 10-year-old grandson in Las Vegas—take up much of his time. But just as he always has, Duque still makes room for music. His life and work in Montana, he says, provides the occasional fodder for songwriting: “This ranch has given me a lot of inspiration—it has quiet places, rivers, meadows. Ideas come to me in places where I can be alone and think.” And this fall, Duque plans to head back into the recording studio to lay down a few new tracks. “I am old,” says Duque, “but my voice is still young. And if the voice is young, the heart is too.”

DOWN BY THE BAY

By Devorah Lev-Tov

A slew of ambitious restaurant and hotel openings in Maryland’s Eastern Shore have put the region on the map for more than just seafood and coastal vibes. These days, visitors are flocking to once-sleepy towns to discover the area’s rich history and natural beauty—and while summer sees these coastal enclaves flooded with visitors, cooler weather and technicolor foliage make fall an ideal time to visit. Here’s where to spend an Eastern Shore weekend.

Friday

Start in St. Michaels, the region’s largest city, at the Wildset, a boutique hotel opened last year by the two sisters behind the acclaimed Nashville restaurant Henrietta Red. Browse ROEN candles and small-batch chocolates at the stylish boutique on site, then snag a seat at the property’s restaurant, Ruse, for a lunch of fresh and roasted oysters and heirloom carrot salad with labneh and pistachios.

After lunch, stroll the town of St. Michaels, stopping at the Lyon Rum distillery for a tasting (a new tasting room with cocktails is in the works) and the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum to learn about the seafaring history of the region. Then head to Easton for a stop at Bonheur, a chic ice cream and pie shop that recently started offering Friday afternoon tea, complete with cucumber sandwiches, house-made scones and seasonal jams.

Next it’s on to Oxford, a historic fishing village about 10 miles south of Easton. Stroll the shoreline, then make your way to Capsize, a waterfront restaurant that takes full advantage of the ocean’s bounty. Start with an Oxford Mule, then get your fix of the local specialty: you can’t go wrong with the crab dip with a freshly baked pretzel roll and crab cakes with fried green tomatoes and Old Bay cheddar grits.

Maryland’s Eastern Shore is adestination for chic shops, buzzy hotels and red-hot restaurants that go way beyond blue crabs.

Photo credits: (left image) Maya Oren, (inset image) Kimberly Kong, (upper right) Melanie Dunea, (right) Parasol Marketing

Begin your day at Rise Up Coffee Roasters, a small-batch roastery that was founded locally and has since grown to 11 locations in the region. For breakfast, head to Easton’s Bagelry, a from-scratch, organic bagel shop. Easton was once home to the courts and governmental offices for the whole Eastern Shore, nabbing it the title of Maryland’s “East Capital.” See the historic courthouse in the town square and the statue of Frederick Douglass, who was born and enslaved a few miles away—and held at the prison below the courthouse.

Pay a visit to the nearby Academy Art Museum, where American and European masterworks are on display in a former schoolhouse dating back to 1820. For lunch, hit up one of several Easton spots run by Bluepoint Hospitality, the brainchild of businessman Paul Prager, who’s spent the past decade investing in the town’s revitalization. At The Wardroom, you’ll find gourmet sandwiches, a food market and a wine shop stocked with European imports. Spend the afternoon browsing Easton’s shops, including Flying Cloud Booksellers, women’s designer clothing store Dragonfly Boutique, antique home furnishing store Wye New?, Trippe Gallery and Troika Gallery.

Stay in Easton for a prix-fixe dinner at Vienna-inspired Bas Rouge, another Bluepoint Hospitality spot. Expect dishes like lime-cured yellowtail amberjack with caviar and a classic wiener schnitzel, plus desserts from pastry wunderkind Melissa Weller, previously of New York restaurants Per Se and Sadelle’s.

Saturday Sunday

Brunch at the Inn at Perry Cabin’s fine dining restaurant STARS is a wellheeled affair. Book a table to nibble on avocado-burrata toast with Chesapeake Smokehouse salmon and omelets made with locally caught crab and cheese from Easton’s Chapel’s Country Creamery.

Before you head home, swing by the Easton Amish Market, with more than 20 vendors ranging from furniture makers to produce farmers. Don’t miss Fisher’s Pastries, where you can pick up local specialties like a slice of Smith Island Cake (a towering yellow layer cake with chocolate frosting) and Maryland Beaten Biscuits (yeast-free biscuits beaten with a rolling pin that are dense yet soft on the inside).

A FORPLaCE US

By Naomi Tomky

By Naomi Tomky

for many Camp Yoshi attendees, the first epiphany about the outdoors comes before even arriving at their pre-supplied personal tent. It happens as they take a long drive down a highway and then slow down for a sharp left onto an unmarked dirt road in rural Oregon. “In our world, that represents danger,” explains Chef Rashad Frazier, the founder of Camp Yoshi. “For us to go mobbing down these roads in a jeep, that brings a sense of security.”

Frazier, together with his wife and brother, created Camp Yoshi to diversify the lens through which people experience the outdoors, primarily by offering upscale guided outdoor adventures geared toward—though not exclusively for—BIPOC, or Black, Indigenous and people of color.

“The outdoors has not been most inviting for diverse communities,” says Frazier. But he grew up fishing, hunting and camping with his family in North Carolina. So, in July 2020, when the stress of closing his New York City catering company and the constant news of

racial injustice started to get to him, he found refuge in the wilderness. Contemplating his next move from the peaceful solitude of Glacier National Park, it struck him that he wanted to help other people experience the same respite. By that fall, the first test trip of 12 campers headed out to Oregon’s Alvord Desert. “They lost their minds,” Frazier says. “It’s kind of cool to watch these grown-ass people witness the stars for the first time.”

This year, trips headed out to more than a half-dozen locations, including Moab, Colorado’s San Juan Mountains and Tanzania. Camp Yoshi does all the planning and provides gear, transportation, gourmet meals and professional photographers to document the trips.

“There’s a narrative that camping means granola,” Frazier says, but like everything else at Camp Yoshi, the food is designed to show guests a different way to get outside. It also helps entice people to try something new. They might not know if they’ll enjoy the wilderness, but at least they can be sure they’ll like braised short ribs

With gourmet meals and awe-inspiring destinations, expedition collective Camp Yoshi is helping new audiences fall in love with the wilderness.

paired with a strong whiskey cocktail. Campers feast on Dungeness crab cake sandwiches for breakfast and eat grilled tomahawk steaks topped with freshly foraged herbs for dinner. “Sitting down and having an epic meal helps you be present,” he says, and it’s the glue that turns Monday’s solo campers into Thursday’s lifelong friends.

Most of the campers come alone, and few have any previous wilderness experience. The legacy of outdoor spaces in North America was often passed down from grandparents and parents, with kids going to an uncle’s cabin in the woods or their father’s secret fishing hole, but, as Frazier notes, this was often only an option for white people. “We were marginalized and kept from these spaces.”

With Camp Yoshi, he hopes to change that narrative and help bring more diverse groups out of their comfort zones. “We’re taking back our power, reconnecting in our own way,” Frazier says. “We’re going down the roads that had fences and signs saying ‘no entry’ or ‘keep out.’” campyoshi.com.

CAMP YOSHI does all the planning and provides gear, transportation, gourmet meals and professional photographers to document the trips.

Photo credits: Camp Yoshi

AMONG VINES

Photo credit: Drew Kelly

Photo credit: Drew Kelly

AMONG THE VINES

It all started with a one-credit course in the history of wine. As a student at Rice University, Texas native Suzanne Deal Booth studied maps, memorized varietals and learned about growing seasons and soil types, sparking a lifelong passion for wine. That undergraduate whim would eventually lead her to transform one of Napa Valley’s most historic estates into a destination for both oenophiles and art lovers.

But for many years, she was solely immersed in her other great passion: art. As a leading arts preservationist and collector, Deal Booth traveled around the globe, training under the legendary French-American collector Dominique de Menil, founder of Houston’s Menil Collection. Deal Booth worked at world-famous cultural institutions like the Centre Pompidou in Paris and oversaw projects including an architectural retrofit of a Napoleonic-era coffee house in Venice.

By Siobhan Reid

Of all the places she traveled, Napa Valley held unique appeal. “I’d been coming here for 15 years before I decided to purchase property,” she says. “There’s something beguiling about the place—the energy, the biodiversity, the rolling hills. It reminds me a lot of Provence.”

In 2010, an evening stroll around Rutherford took her past Bella Oaks, an historic vineyard that had produced some of the region’s earliest single-vineyard Cabernet Sauvignons. Deal Booth paused to take in the estate’s wild scenery and crumbling beauty. “I was struck by its beautiful setting below the Mayacamas,” she says. “The vineyard house didn’t look like much, but it had lovely bones.” When she learned the property was being entered into an estate sale, Deal Booth and her thenhusband decided to put in an offer. “It was a pretty spontaneous decision,” she admits, adding “but it quickly felt like home.”

At a 150-year-old estate in Napa Valley, a legendary collector and philanthropist has created a wine and art destination that transcends genres.

Upon acquiring the property, Deal Booth got to work, tapping David Abreu, one of Napa’s top vineyard managers, to gradually replant the winery’s 12.5 acres and Los Angeles-based architect Michael Maltzan to reimagine the humble vineyard house. For the first few years, Bella Oaks’ fruit was primarily sold to a neighboring vineyard, but in 2017, Deal Booth decided to double down on winemaking. She hired renowned oenologist Michel Rolland and winemaker Nigel Kinsman and oversaw the estate’s conversion to organic and biodynamic farming methods. Earlier this year, the 2019 Bella Oaks Proprietary Red received 100 points from wine critic Antonio Galloni—a sign of great things to come for the reborn estate.

But for Deal Booth, one of the greatest joys has been the art. She has installed several works from her extensive personal collection amid the winery’s landscaped gardens, olive orchards and tidy rows of vines: terra cotta structures from Mexican artist Bosco Sodi, an abstract cherry-red statue by Joel Shapiro, Max Ernst’s Le Genie de La Bastille and the pièce de résistance, a mirrored cube pavilion by Yayoi Kusama. After tasting the estategrown Cabernet Sauvignon, visitors can stroll the Bella Oaks estate and view the collection on a private tour.

Deal Booth recently acquired an adjacent winery, which she is currently overhauling with celebrated Thai architect Kulapat Yantrasast. She plans to open a dedicated tasting space and offer an expanded hospitality program of wine tastings and art tours. But for now, she’s simply enjoying the fruits of her labor. “This place has become my great love,” she says, looking out to the vines.

But for Deal Booth, one of the greatest joys has been the art.

Photo credits: (above) Erin Feinblatt, (top center) Matt Morris

FOUR MORE NATURE-CENTRIC DESTINATIONS FOR ART LOVERS Art En Plein Air

Glenstone Museum Potomac, MD

Set on 230 acres of rolling pasture and woodlands outside D.C., this private museum houses the collection of art world power couple Mitchell and Emily Wei Rales. A recent $200 million expansion brought about additional indoor and outdoor spaces showcasing American postwar masterpieces by the likes of Ruth Asawa, Robert Rauschenberg and Mark Rothko. The highlight is The Pavilions, an exhibition complex centered on a vast water court planted with more than 4,000 water lilies.

Tippet Rise Art Center Fishtail, MT

In 2019, Pritzker Prize-winning architect Diébédo Francis Kéré opened a pavilion on the grounds of Tippet Rise Art Center, located on a working ranch just north of Yellowstone National Park . It was an addition that cemented the institution’s global status, rounding out the already impressive collection of works by names like Alexander Calder, Patrick Dougherty and Stephen Talasnik. During the warmer months, Tippet Rise hosts classical chamber music recitals amid large-scale sculptures, allowing visitors to contemplate the interplay of art and nature.

Storm King Art Center New Windsor, NY

A favorite refuge of harried New Yorkers, this open-air museum in Hudson Valley is home to more than 100 giant sculptures, spread over 500 acres of undulating hills and verdant fields. Visitors can walk, bike or take a tram around the expansive grounds, passing by site-specific commissions by heavyweights like Andy Goldsworthy, Maya Lin, Richard Serra and, most recently, Sarah Sze.

The Chinati Foundation Marfa, TX

The West Texas town of Marfa has come to be synonymous with artist Donald Judd, whose minimalist works are scattered around the dusty grounds of this military base turned art museum, founded by Judd in 1986. Other draws include works by Dan Flavin and Richard Long, as well as a large-scale artwork by Robert Irwin—the only permanent, freestanding structure created by Irwin as a total work of art—installed in the museum’s central courtyard in 2016. —S.R.

Life on the Edge

Behind every blade, there’s a story, and modern cutlery shops across the country are bringing those tales to diehard knife nerds and casual home cooks alike.

By Carey Jones

By Carey Jones

the shelves at San Francisco’s Bernal Cutlery— aged rice vinegars and Oakland-made salsa macha , handmade ceramics, a thoughtful array of cookbooks. But further back, glass cases highlight what the shop is really about. Here you’ll find hand-forged gyuto and santoku knives from centuries-old Japanese makers, vintage carving sets, carbon steel cleavers. “If you’re not versed in knives, it might look like a weird culinary torture chamber,” laughs co-owner Josh Donald.

With a deep respect for the craft behind each tool, and for its potential in the kitchen, Donald and his wife and co-owner, Kelly Kozak, don’t just sell knives; they educate, and build community, around them.

A good knife is the single most important tool in a chef’s arsenal, and chefs are known to be fanatical around the subject. (A properly sharp knife is not only easier to work with, according to Donald, it impacts the food’s very taste, as a clean cut ruptures fewer cells and allows less flavor-altering oxidation.) But today’s knife shops appeal far beyond the industry, attracting home cooks to a world at the confluence of design, craftsmanship and history.

Donald and Kozak amassed their expertise over decades. In 2005, with their first son in a stroller, Donald sharpened knives around the neighborhood to bring in extra cash. Eventually, he began working with professionals. It gave him a window into what chefs were really using: “Not the status symbol knives,” he says, “but what’s truly a good tool.”

That knowledge sparked an interest in selling knives. Their home business expanded into a stall in a culinary marketplace, then to a stand-alone shop and eventually to this light-filled storefront on bustling Valencia Street. But the Bernal Cutlery crew remembers their scrappier days fondly. “It was a democratizing space,” says Donald. “Chefs would come in on their day off to get their knives sharpened, free from the hierarchy of their workplace.” It had the feel of a bar, or a barber shop, agreed Kozak—a beloved community fixture. “We interact with so many different types—people doing butchery in their backyards,

woodworkers, hunters,” says Kozak. “We try hard to make it an environment where they don’t feel intimidated.”

Bernal Cutlery sells knives from around the world, both well-made industrial products and hand-forged tools. But they have a particular emphasis on Japanese knives. “There’s been a continuum of craftsmanship in Japan,” says Donald. “They haven’t lost hand-working traditions.” Bernal works with small makers with generations or even centuries of history. Particularly popular are Japanese interpretations of the classic Western chef’s knife, a departure from Japan’s own tradition of using different blades for vegetables, fish and so on. “They applied their precise working style to that multipurpose tool,” he says. (Donald’s 2018 book, Sharp, is a fascinating deep dive on knives generally, and Japanese knives in particular.)

“If you’re not versed in knives, it might look like a weird culinary torture chamber ”

Any food-lover could get lost browsing

Photo credits: (above and below) Bernal Cutlery

Thousands of miles away, it was Bernal

Cutlery that inspired Evan Atwell to open his own shop, Strata, in Portland, Maine. He, too, grew his business over time, starting as a butcher who sharpened knives on the side, then opening Strata in a business incubator with a 90-square-foot sales floor before moving to a larger shop with more than 600 knives in stock.

Once customers venture into the world of specialty knives, Atwell says, an entire world opens: “They get hooked. Sharpness becomes addictive.” Strata’s social media following—nearly 10,000 strong on Instagram—reflects their obsession. “Knives are sexy, and sex sells,” he says. While he views the social media side of his operation as a necessary evil, there’s no doubt that it has helped drive business, he says. “As with any esoteric subject, there’s a small but passionate user network that really geeks out with each other.” And younger generations, he says, “disheartened by the throwaway economy,” are drawn to products with a story and a legacy.

Social media isn’t the only force behind newfound knife fans, says Craig Field, who, with Tina Chon, owns Denver’s Carbon Knife Co. “Over the pandemic, people found themselves at home, cooking daily, many for the

public. “We love hearing someone’s excitement owning their first real Japanese knife,” Field says. “The geometry provides such a pleasant, effortless feeling when cutting. It’s eye-opening.”

“Younger generations are

Jacqueline Blanchard and Brandt Cox, co-owners of Coutelier in New Orleans and Nashville, also approached their store from a culinary background. “As professional chefs,” says Cox, “we wanted to sell exactly what a chef would need for their knife roll.” Having traveled extensively through Japan, Blanchard and Cox highlight makers like Moritaka Hamono, outside Kumamoto, a 29th-generation family operation dating back to 1293. “You have to put some reverence and respect on that,” Cox says; “On a culture that’s so much older than, as Americans, we can even fathom.” At Coutelier, he laughs, “You don’t have to teach a new employee how to do inventory. You have to teach them basic culinary skills and Japanese history.”

first time,” he says. From bread-making to fermenting, home cooks found new passions, and wanted the proper tools.

Both former professional chefs, Field and Chon have kept their ties to the industry while educating a broader

A beautifully crafted knife is worthy of attention on its own. But ultimately, it’s the connection between the knives and the chefs that use them, the traditions they stem from, and the cultures they reflect that make them so compelling. “The more involved you get in this subject, the more it becomes an anthropological and scientific study,” Evan Atwell says. And if it ups your game in the kitchen? So much the better.

Photo credits: (bottom left) Carbon Knife Co., (above) Strata

drawn to products with a story and legacy

”

THE FIRST TO CHANGE

4069

Road Greenough, MT 59823 877-251-2841 thegreeno.com

According to the Japanese poets: the scarecrow, insect sounds, chrysanthemums, and the moon. Here, the willow swaps its green for yellow feathers. The emptiest stubble fields that fill with our large houses and roads. The so-called dead. Or the happiest people, who have the most to lose. The freshness of the words we use most often. The wind today grows restless to be done with leaves. Change sounds good when one is sick of oneself. My mother’s blood tests came back negative. Yesterday, she thought she was going to die.

The beginning of autumn, Buson wrote. Why is the fortune -teller looking so surprised? Young girls, saplings, snap peas entangled in their vines—if to grow is to become larger, to grow old must involve a trance, slipping out of the body into vaster realms of memory.

If time is our own construct, could we build it without beginnings or ends, with lamps, but no clocks and no miles? My mother slips like the creek slips through the afternoon, every day quieter and more shallow. First to change is the moment, next perhaps the months and years.

Last of all, perhaps all those who fear uncertainty.

—Melissa Kwasny

Autumn Sunrise by Jerry Schmidt

©2022 The Last Best Beef LLC. All rights reserved.

Backcountry