11 minute read

Father Pius

FEATURE

Father Pius Remembers: A Teacher’s Long Journey

By: Thea Sullivan

When he was young, Laszlo Horvath—Priory’s own Father Pius—was clear about one thing. He wanted to go to university and become a teacher. “Teaching was always in my mind, even as a child,” he admits.

The quest to fulfill this goal became the defining journey of his life, guiding him over one seemingly insurmountable obstacle after another, driving him out of his homeland and from behind the Iron Curtain, and eventually landing him in California where he’s lived now for fifty-six years.

At almost 87, Father Pius looks back on his choice to leave Hungary with mixed feelings. “I sometimes say to myself, ‘Would I have done that, taken that step of leaving my country and my family and everybody, if I had given it more time to think it over?’ I still don’t have the answer to that.”

But for a young person growing up in Eastern Europe in the turbulent years before, during and after World War II, getting an education was difficult, especially as an aspiring Benedictine priest. There were stops and starts, shifting borders, risks to consider and sudden decisions to be made.

During his school years, an early Communist takeover and subsequent war led to the redrawing of national borders, and the Hungarian village where his family lived was suddenly part of Czechoslovakia. To avoid attending a Czech-speaking school, he had to move in with his grandparents in Hungary.

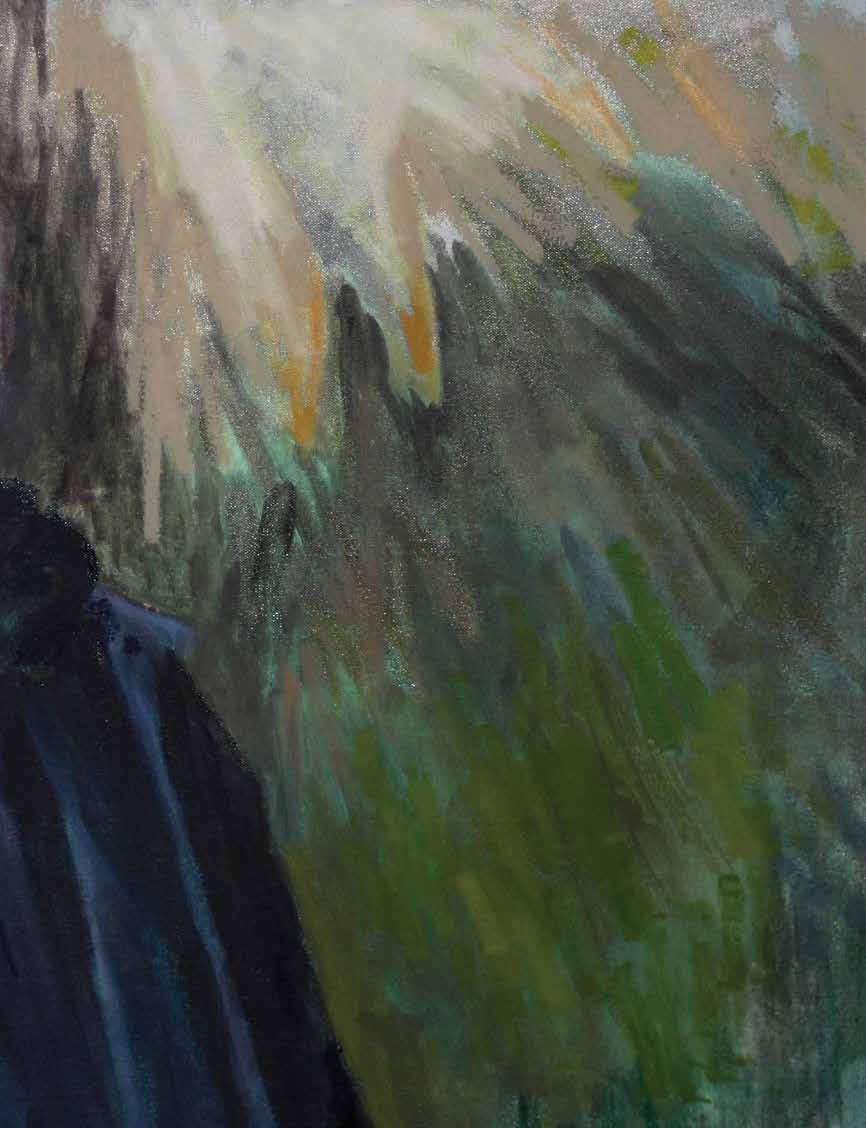

Painting of Fr. Pius by Zoe Ciupitu, Class of 2009

At his new Benedictine school, he tutored small groups of younger students. “My family was not well off, so I was trying at least to earn my tuition,” he explains. Though only in seventh grade, he discovered he loved teaching. “My idea, my purpose, was to study to become a priest and a teacher. That’s what Benedictines did,” Pius says.

A few years later, Laszlo’s plans were once again thrown into chaos. In 1945, just as he was starting high school, the war ended and the new Communist regime closed the schools. He moved back home to Czechoslovakia and joined an “underground school” run by Father Christopher, a teacher who, many years later, would help establish the Priory and invite the younger monk to join him in California.

Studying without a school was only half the battle for Laszlo. He also had to cross the border into Hungary to take an annual exam. Permits were hard to come by since the new Soviet regime fomented tension among its satellites to prevent uprisings. Many times, he crossed illegally, swimming across the wide Danube River or scrambling across chunks of ice to get to the other side.

Finally, after four years of piecemeal education and clandestine river crossings, he received his high school diploma.

Next, he entered the novitiate at Pannonhalma, the Benedictine abbey in Hungary, a cause for celebration but also sadness. The seven years of seminary and teacher training would mean a long exile from his family. Given heightening political tensions, a single visit

home to Czechoslovakia might mean never returning to Pannonhalma again.

As it would throughout his life, Pius’s commitment to education exacted a steep price. With only a year to go until his ordination and with teacher training and university finally within his grasp, the Soviet regime cracked down further. The Benedictine order was reduced by three-quarters, and Laszlo was transferred, along with his final-year classmates, to an overcrowded diocesan seminary to complete ordination. He was luckier than some, but plans for university study were once again on the chopping block.

“I had to take off my scapular,” Father Pius remembers, pointing to his robes, “and dress like a secular priest. That was a heartbreaking experience.” The seminarians were cold, poorly fed and crammed into a space designed for half their number. And they had to watch what they did and said. “We were spied on by moles,” explains Pius, “including by some of our teachers under pressure by the government.” They listened to the radio program Voice of America, but it was risky. “It was hard to know who to trust,” Pius says.

Such risks continued as the newly ordained Father Pius was assigned to parish work. “You had to be always careful, who you talked to, how you preached. Because the system was spying on you,” he says, but he wants it known that he didn’t leave the country out of fear. “I was cautious,” he explains. “I couldn’t always avoid compromising situations, but somehow I managed.”

Studying without a school was only half the battle for Laszlo. He also had to cross the border into Hungary to take an annual exam. Permits were hard to come by, since the new Soviet regime fomented tension among its satellites to prevent uprisings. Many times, he crossed illegally, swimming across the wide Danube River or scrambling across chunks of ice to get to the other side.

What propelled him to leave, once the Hungarian Uprising of 1956 temporarily opened the borders, was the same drive that had propelled him across the icy Danube years earlier. “I wanted to be a teacher,” he says, and that meant leaving Hungary to complete his studies.

He remembers saying to himself, “’I will find a university for myself. Someplace in the West. In a free country.’ I didn’t know much about the possibilities, but I knew that there must be something.”

The night he crossed the border into Austria with a classmate from seminary, he sensed the hand of Providence protecting them. The Russian guards drunkenly asked for money, but let them pass. The marshy, wet stretch of land where they crossed was a place tanks couldn’t follow. And a peasant cart showed them the way.

Pius recalls, “All you could see were those ageold trees and the muddy area and the dark sky. And you think, ‘When am I going to see my people, my country again?’”

There wasn’t much time for reflection. That same night, he and his classmate found themselves in Austria, in a school building packed with migrants. Pius stood up all night, with no place to lie down. “I said, I am getting out of here. I am not staying with this many people.”

He left before dawn to find the local pastor. “It was all dark. I said, how can you find a pastor? Find the church. How can you find the church in the darkness? Wait until they ring the Angelus bell in the morning. Follow the song.”

It worked. At the local parish house, he was given dry clothing, breakfast, and bus fare to Vienna, where Pius had the address of a fellow Hungarian Benedictine. That very morning, he arrived and announced to a priest in Vienna that he wanted to go to university in Belgium. “Forget it,” the priest said. “Go to Fribourg in Switzerland. There is a Catholic university there. I already have a scholarship for you, a scholarship for refugees. Be at the railroad station in the evening. They will put you on the train.”

“That same night I was already in a nice, clean, warm bed in Switzerland. It all happened very quickly,” marvels Pius. Was this God taking care of him? “Always,” he says. “My way was paved.”

Father Pius’s way, though paved, continued to have unexpected twists. After his years at the university in Fribourg, where he mastered German, French, and even the difficult Swiss-German dialect, he hoped to teach in Germany. But his Benedictine superior in Rome had other plans—to send him to Brazil.

“I didn’t want to go to Brazil,” Father Pius says. The only other option was California, where a Benedictine monastery and school was in the works. Pius knew four of the monks already, including Father Christopher from his high school days, and he could finish his studies at Stanford.

And so his quest to become a teacher led him here to California, to a new continent and a brand new life in another new language.

“I think I was the first Hungarian Benedictine to travel on a jet plane,” he says with a wry smile.

Father Pius was only thirty when he first arrived at Priory. He’s eighty-seven now, and his years as a German and Latin teacher are well behind him, but he looks back on them fondly. His first students helped him learn English, including American slang, and when girls arrived at Priory in the early nineties, he welcomed the new influx of energy. They added more “human society,” he says.

Father Pius’s playful smile and affectionate nature endeared him to students, and he’s always forged spe- cial connection with the smallest Priory residents, the children of on-campus faculty. Kate Molak, daughter of Head of School Tim Molak, remembers his happy greeting from when she was little: “Hello, neighbor!” Perhaps his trademark generosity stems from the deprivations of his youth. “I know from my own childhood that it can hurt when the grown-ups ignore you,” Father Pius has said. “Not to hurt you, but just as if children are not yet completely human, which is a great, great mistake. Because kids need a lot of atten- tion and help to build up their egos, (to feel that they) count for something.”

He knows little gestures can mean a lot, as when he sought to connect with one shy seventh grad- er. “She wasn’t even my student, but somehow we always crossed paths and I greeted her. She’d say, ‘Good morning,’ very shyly. So I started offering her a high-five. And the others watched, thinking what will happen now? She reciprocated.” The memory makes him laugh. “These things taught me a lot, gave me some confidence and satisfaction. Even if you wonder, what am I going to do now? There is something always to give.”

Now in fragile health, Father Pius is reflective about his choices, the challenges of living in community, and the state of the world. He has no easy answers about the future of Priory once the monks are gone. “That’s the great unknown,” he says. He cautions against the mythologizing of monastic life. It’s difficult, he says. “You are not hand-picked by God so you fit together perfectly,” he explains. “You have to work on it. That’s your challenge, because that’s the ideal and the idea you represent toward others.” And he reminds us it’s not just monks who have to learn to get along. “That’s what human society is,” he says. “You can see today that we are unhappy because we cannot live together. At so, at least compassion, gratitude, that was my response. You try to do what little you can to help people.” Even today, when he finds himself troubled by the state of the world, or by the persistent gap between rich and poor, he looks for what he calls the “human element,” those moments of connection and compassion that can always be found, no matter how difficult or bleak the circumstances. “I learned that during the war,” he says. He remembers when his family lived on the front line and Russian soldiers regularly entered their home to take food or find warmth. “They didn’t burn down our houses,” Pius concedes, “And they would cry when you mentioned their children. You’d say, “Do you have a baby?” and they would show you photographs.” Then there was the Russian child soldier who’d lost both his parents in the war. “He must have been my age,” Pius says, “Fourteen. And he discovered my sister and myself, and my mother (my father was away in the military), and he needed company. He kept coming. And Mother gave him food. Mother’s cooking was better than the military’s cooking. He had nobody. He was just a kid.” The family attempted to communicate with him despite the language barrier. Father Pius remembers how the boy’s machine gun scared his mother. “In Hungarian, and in sign language, she said, ‘Put down that damn thing!’ And the boy obeyed.” Now, after almost two hours of talking, Father Pius is growing tired, and the visiting nurse is coming soon to pay him a visit. But he smiles as he shares one more detail about the Russian boy from over seventy years ago. “One time he wanted to give me a souvenir. So he opened his pack and gave me a bullet.” He laughs quietly, remembering. “I’ll never forget Nikolai,” he says.