14 minute read

THE CAR FROM PARIS

TALBOT-LAGO Grand Sport

By Peter M. Larsen

The first Talbot-Lago T26 Grand Sport to receive a body was chassis 110101. The two-door coupé, built by Jacques Saoutchik, was the star of the 1948 Salon de l’Automobile in Paris.

“I'M READY FOR MY CLOSE-UP.”

Gloria Swanson as Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard, 1950

In the end, it was Anthony Lago, the astute businessman, who never paid full price for anything, who was forced to swallow his own medicine and sell out for a pittance when Henri Pigozzi of the French automaker Simca devoured what was left of Lago’s factory and company in the summer of 1958. Two years later, he died of heart failure. Lago was overweight, a smoker, and only 67 years old. For years, he had looked like a man ten years older: tired, ill, and worn out. It is no wonder — he had been fighting every day of his life to keep Talbot going since he finally took over the French company in June 1935.

In the beginning, things had gone well. In spite of Lago having to pull the company out of the clutches of inept owners and near bankruptcy, as well as fend off hostile takeover attempts, not to mention the effects of the Great Depression, the years up to World War II had been reasonably good. But since 1939, there had been no windfalls, no strokes of luck, nor merely steady growth in which he could have taken comfort. Instead, there had been a world war, occupation, crippling government taxation, another bankruptcy, and a vicious circle of steady decline. The last years of his life had been bitter indeed, and selling out to Pigozzi for a handout broke his heart.

Above: A rather dapper Anthony Lago in August 1937, two years after he took over Talbot. Left: Two or three of the flamboyant Saoutchik cabriolet-roadsters were built. Chassis 110120 is the only cabriolet that survives with its original coachwork, seen here at a Belgian Concours in the 1950s.

It was a different man who arrived at the Talbot factory in Suresnes outside of Paris in 1933 having carefully constructed the absolute deal of his life with its British owners: a dapper Anglo-Italian gentleman with no money but some sophistication, full of energy and vision for the moribund company, which Owen Clegg, his predecessor, had managed into the ground. At the age of 40, Lago was an accomplished wheeler-dealer, who had worked very hard to get where he was, and from the very beginning, he had allowed nothing and no one to get in his way.

Born in Venice on March 28, 1893, he was christened Antonio Franco Lago. The family was upper-middle-class with both social and cultural pretensions. The Lagos soon moved north to Bergamo, where Antonio’s father managed the local civic theater. There, young Antonio grew up surrounded by people of letters and music. Lago flirted with the nascent Fascist party in his youth — an involvement that ended with a bang. He soon found that militancy had supplanted early idealism, and Lago criticized the movement publicly. Fascist Blackshirts began to hunt him, and this culminated in an incident shortly after the Armistice where Lago was attacked at gunpoint in a local café.

They Look like nothing else.

Fortunately for him, the fascists shot the café proprietor first, and Lago was able to throw a hand grenade, which he not uncoincidentally was carrying in his pocket, making his escape in the ensuing melée. Lago fled to America, worked as an engineer for Pratt & Whitney, and later returned to London where he became an Isotta Fraschini dealer and acquired the European rights to the Wilson pre-selector gearbox — for which he deftly managed to pay nothing. He never set foot in Italy again.

By late 1932, Automobiles Talbot S.A., which was owned by the British Sunbeam-Talbot-Darracq combine (STD), was on the verge of bankruptcy. Lago presented himself to STD’s management as the “man to the rescue” and was sent from England for a few weeks to look over Talbot and make a report as to what could be done. Upon examination of the moribund Talbot factory, Lago found it in shambles. Chief engineer and fellow Italian Walter Becchia was on the verge of leaving, and the workers were uncaring and demoralized. The few cars being turned out were poorly put together. But beneath the dust and the cobwebs, Lago could see a plum ripe for the picking. After returning to England, instead of recommending liquidation, Lago suggested to STD that he be made managing director of Talbot in France for a two-year period with a put option to buy the factory at any time at its 1933 value.

He returned to France in early 1933 to rake the coals out of the fire with a doozy of a contract in his back pocket that would hand everything over to him if he played his cards right. He did. In fact, the coals were raked out so ruthlessly that Lago ended up owning the company without paying anyone anything. As payment, he simply assumed an old £500,000 debt that STD still owed the bank due to a loan taken in 1924 with the French factory as collateral. Imagine: not only had Lago become a carmaker without a centime to his name; through this deal he had just become STD’s biggest creditor, and this was all part of the plan. In 1936, he let Talbot go bankrupt in connection with the great strikes in France, thereby wiping out all debt. STD couldn’t call in its debt with the liquidators, as Lago was the first creditor in line. In the end, Lago obtained Talbot scot-free.

While conducting these scurrilous financial dealings, he also set about transforming the company. The entire product line was redesigned by Joseph Figoni, powerful new six-cylinder single-cam 4-liter engines were introduced, and Lago’s Wilson

Opposite page: The 1948 Talbot-Lago T26 Grand Sport Fastback Coupé by Figoni, owned by Robert Kudela, was a popular Best of Show Nominee in 2018. It also won the Vitesse ~ Elegance Trophy, having “zipped” along beautifully on the Tour d’Elegance. Left and below: Seen on the Pebble Beach Tour d’Elegance in 2017 and below at Le Mans in 1950, chassis 110105 raced at the 24 Hours of Le Mans from 1949 to 1953. Its first owner, the French driver André Chambas, ordered the sporty coupé body from the little-known coachbuilder Contamin-Besset.

pre-selector gearbox was slipped into the chassis. Then Lago went racing. Suddenly, Talbots were a hot commodity, and it is no exaggeration to say that the rest is history.

When the chassis design for the T26 Grand Sport was laid down toward the end of World War II, it was Lago’s intention to produce a very exclusive road-going sports chassis for the carriage trade. A chassis that in its conception, feel, and driveability was as close as technically possible to his glorious Grand Prix cars. In that sense, it was not really a new design: the layout and most mechanical details from the prewar GP cars were retained. This meant that the Grand Sport was a true sports car rather than a grande routière such as a Delahaye or a Delage. The target group was a wealthy and very sporting clientele, which on the one hand wanted a fast daily driver, and on the other, would not be averse to entering various racing and rally events as a privateer.

In retrospect, we know that even if the target group may have been there, the market certainly was not, as the rich had become careful about displaying their wealth in the austere postwar political climate. Market research, customer clinics, and scientifically targeted product development would have been totally alien concepts to a man like Anthony Lago. His thinking was much simpler: “I have developed, proved, and honed my chassis and engines in gruelling competition since before the War. I am now selling you a perfected road car chassis, which has much of the power, road holding, and strength of my Grand Prix racing machines. Surely, you must covet that and buy it!” They didn’t. Lago was flying by the seat of his pants, and this time his intuition failed him. For that we should all be thankful. Had he been “smarter” and taken a cooler and more distanced look at the new world surrounding him in 1945 and 1946, the Grand Sport chassis would never have come into existence.

The bare chassis made its debut at the Paris Salon in October 1947, and the first bodied cars were shown there the following year. As it turned out, production was extremely limited. In four years, from 1948 to 1952, Talbot produced a total of 32 documented GS chassis: 29 on the original short 2.65-meter wheelbase that was identical to that of the prewar racers, and three toward the end on a stretched 2.80-meter wheelbase. All were bodied by the crème de la crème of French coachbuilding. Saoutchik was the most prolific, but Grand Sports were also bodied by Chapron, Franay, Figoni, Dubos, Antem, and others. Exported chassis were bodied by Pennock in Holland, Van den Plas in Belgium, Graber in Switzerland, and Stabilimenti Farina in Italy.

Some Grand Sports turned out to be quite competitive and were rallied and raced enthusiastically by their owners. Others were laden considerably with voluptuous bodies. These extravagant creations blunted performance somewhat, but their lascivious beauty more than compensated for these shortcomings. Owners and coachbuilders avidly entered these latter Grand Sports in many of the postwar concours d’elegance in France and abroad, often winning grand prizes for elegance. The cars still do so today whenever they are shown. They look like nothing else. They are remarkable. They draw crowds, and deservedly so.

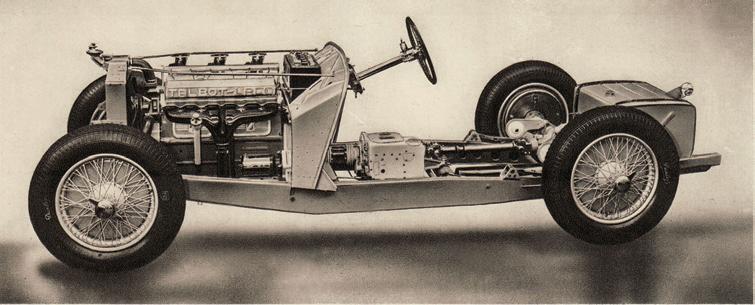

Left: The short-wheelbase Grand Sport chassis as introduced in 1947 was a prewar Grand Prix car in disguise. Below: Grand Sport chassis 110112, built in 1949 by the Parisian coachbuilder Antem, was a special order with full Grand Prix mechanicals and close to 300 hp. It was built for Marcel Paul-Cavallier, who had been on the Talbot board of directors since 1948.

Over the years, criticism has been levelled at the extreme shortness of wheelbase of the original Grand Sport chassis, coupled with the relatively tall powerplant, the large 18-inch wheels, and the massive 120-liter gas tank. The argument is that at only 2.65 meters, it complicated the work of the carrossier unnecessarily and resulted in bodies of dubious aesthetics. While it is true that stretching the chassis to 2.80 meters for the last cars was probably a concession (too little, too late) to the coachbuilders, in hindsight, this criticism misses the point.

First, Anthony Lago wanted precise sports car handling, so the GS was conceived strictly as a two-seater. Second, since there was no money left in his destitute company to develop new mechanicals, Lago had to work around a heavy engine with prewar origins and a heavy gearbox, and still aim for relatively light weight. The car had to have a short chassis, which would be very fast on the road and competitive on the race circuits. And this combination he certainly achieved.

The Wilson pre-selector gearbox was left unchanged, as it offered extremely fast shifting compared with standard gearboxes at the time. With its three large Zenith carburetors and aluminum cylinder head, the twin-cam 4.5-liter sixcylinder engine put out an impressive 190 hp. The chassis featured a transverse-leaf front suspension, and without a body it weighed in at 850 kilos, compared with 1,280 kilos for the standard Lago Record passenger car chassis, a savings of more than 400 kilos. This was enough to make the Grand Sport the fastest production chassis in the world — at least for a short while.

In Anthony Lago’s mind, the chassis he presented to the world in 1947 was destined for the grand cru sportsman and chic Parisian society in equal measure. It was a grand gesture, the final flowering in France of the great tradition of the truly custom and profoundly bespoke motorcar. This chassis was one of the last expressions anywhere in the world of grand luxury in the true sense of that word. Not just grand luxury understood as the amount of leather, wood door-cappings, thick carpets, drinks cabinets, or other accoutrements provided to gratify the owner. The sybaritic nature of the Grand Sport lay in its outrageous exclusivity. It was something for the very, very few. Not just because of its price, which was stratospheric, or its limited practicality, which was irrelevant.

The allure was the Grand Sport’s inherent good taste and rare appeal, which were not readily understood by the majority. Here was a car that was chic, ritzy, aristocratic, and sharp as a knife all at once. The Grand Sport chassis was a thing of grand luxury because it appealed to a genuinely sophisticated clientele, who could appreciate its pedigree and aesthetics. Grand luxury because of the truly unique hand-crafted bodies this chassis demanded. Grand luxury because of the elite gatherings on the racing and concours circuits to which this car gave admission, no questions asked. The Talbot-Lago Grand Sport was the embodiment of French haute couture in metal. It truly was The Car From Paris and just as truly the last of its kind.

It is indisputable that after the War, Lago went from being a whirling dervish in business to an aging and obdurate

Above: Grand Sport chassis 110121 by Franay was first shown at the Paris Salon in 1949. For the car's third grille treatment in as many years, Marius Franay copied Ferrari 212 Inter chassis 0177E, which he had seen at the 1951 Paris Salon. Left: Chassis 110156, a two-door coupé built by Saoutchik in 1951 and owned by the Blackhawk Collection, is a former First in Class winner at Pebble Beach.

It truly wasThe Car from Paris

and just as truly the last of its kind.

man, incapable of recognizing change and reacting properly to it. He and his tiny Talbot company remained alone and windswept in a bleak market with no corporate bankroll or government subsidy to keep him afloat. Yet he managed to manufacture these gorgeous and unique sports cars, run a racing department, and win the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1950. With some truth, evil tongues could say that he didn’t know when to quit.

It is a paradox, but there are only simple answers to the whys and the wherefores of Anthony Lago’s life. As is often the case, the motivations for greatness are banal and explanations pedestrian. It was a quest for glory, pure and simple, no questions asked, and no quarter expected. Lago was a man for whom the end always justified the means, no matter how devious. He was a hustler who burned with a passion equal to that of the greatest and most celebrated automobile constructors in history. A man who would not and could not accept defeat. A man who would get up, pick up the pieces, salvage what he could, and fight on in situations where others would simply have left the building. A man who was as single-minded as a young Ettore Bugatti or as committed as an Enzo Ferrari, a Carroll Shelby, a Giotto Bizzarrini, or any of the other legends whose lives and careers we continue to celebrate.

Right: Each of the 36 Grand Sports was unique. This coupé is the only T26 chassis bodied by the coachbuilder Pennock in the Netherlands. It was ordered by amateur racing driver Maneer Reichmann, who specified several modifications suitable for rallying.

Anthony Lago was not merely a mechanic, an engineer, or a businessman; he was an artist, and his canvas was car making. As such he should be judged. However, like an aging Henry Ford, the downside was a sclerotic insistence in later years that times had not changed and that old solutions were still viable. And like a sclerosis, the disease disseminated itself slowly and insidiously into all things. The culmination, when Lago was eventually forced to sell out to Simca, was a meek disappearance like a blip on a screen. It was not fair, nor was it an even playing field. Being eaten by Henri Pigozzi did indeed break Lago’s heart, but he would have expected no pity. Lago knew the rules, never questioned them, and entered the game. He played it with elegance, beauty, and great style.

The Talbot-Lago T26 Grand Sport is his swan song, his enduring legacy.