Charles Rogers END

Saginaw, 1999

Kevin Hart

OFFENSIVE LINEMAN

Birmingham Brother Rice, 1974

Luis Sharpe

OFFENSIVE LINEMAN

Detroit Southwestern, 1977

Anthony Adams

OFFENSIVE LINEMAN

Detroit King, 1997

Gabe Watson

OFFENSIVE LINEMAN

Southfield, 2001

Jake Long

OFFENSIVE LINEMAN

Lapeer East, 2002

Antonio Gates

TIGHT END

Detroit Central, 1997

Mill Coleman

QUARTERBACK

Farmington Hills Harrison, 1989

Jerome Bettis

RUNNING BACK

Detroit Mackenzie, 1989

Tyrone Wheatley

RUNNING BACK

Dearborn Heights Robichaud, 1990 (captain)

Mark Ingram Jr.

RUNNING BACK

Flint Southwestern, 2007

Jake Moody

KICKER

Northville, 2017

Mark Messner

DEFENSIVE LINEMAN

Redford Detroit Catholic Central, 1983

Mike Lodish

DEFENSIVE LINEMAN

Birmingham Brother Rice, 1984

Nick Perry

DEFENSIVE LINEMAN

Detroit King, 2007

Pepper Johnson

LINEBACKER

Detroit Mackenzie, 1981

Pat Shurmur

LINEBACKER

Dearborn Divine Child, 1982

Jon Jansen

LINEBACKER

Clawson, 1993

LaMarr Woodley

LINEBACKER

Saginaw, 2002

Tony Dungy

DEFENSIVE BACK

Jackson Parkside, 1972

John Miller

DEFENSIVE BACK

Farmington Hills Harrison, 1984 (captain)

Todd Lyght

DEFENSIVE BACK

Flint Powers, 1986

Courtney Hawkins

DEFENSIVE BACK

Flint Beecher, 1987

John Herrington

COACH

Farmington Hills Harrison, 1970-2018

POSITION: Running back VITALS: 6-feet-1, 235 pounds

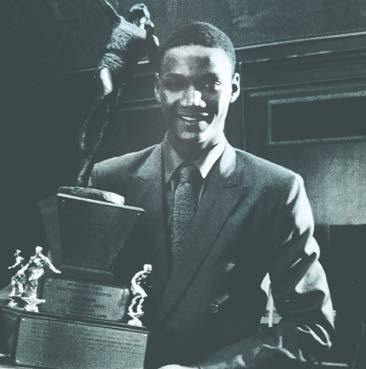

HIS LEGACY: Nicknamed “The Bus,” Bettis was as good a linebacker as he was a running back in high school, although bowling was his favorite sport as a kid. He was rated the top prospect on Mick McCabe’s Fab 50 — and ended up winning a Super Bowl in his hometown and earning a bust in Canton, Ohio.

AT MACKENZIE: In 1989, a knockout ground attack with Bettis at fullback and Walter Smith at tailback led the Stags to the PSL’s west division title and their first berth in the state playoffs. Bettis gained 1,365 yards on 123 carries — 11.1 yards a carry — and scored 14 touchdowns. He batted down nine passes as a middle linebacker. Still, he knew his role: “It’s to provide the dirty yards. Those are the grind-’em-out yards where you only get two or three a crack. That’s when you really earn the yards — when you’re in the trenches.” Coach Bob Dozier said: “He’s a bear of a football player. Jerome is exceptionally fast, unusually strong and very durable.”

IN COLLEGE: Bettis picked Norte Dame over Michigan. As a sophomore, he scored a school-record 23 touchdowns — 19 rushing, four receiving — and totaled 1,328 yards from scrimmage. Instead of two or three yards a crack, he averaged 6.1 a carry and 10.8 a catch. As a junior, he topped 1,000 yards again — and decided to turn pro.

IN THE PROS: The Los Angeles Rams selected Bettis with the 10th pick in 1993. Earning a new nickname — the Battering Ram — he made All-Pro with 1,429 rushing yards and won the offensive rookie of the year award. He made the Pro Bowl in 1994. After a down year, he was dealt to the Pittsburgh Steelers, where he rushed for 1,431 yards, made All-Pro again and was voted comeback player of the year. He spent his last 10 seasons in Pittsburgh, with six 1,000yard seasons and four Pro Bowls. He retired after the 2005 season with 13,662 yards — fifth all-time — and 91 touchdowns. His last game came at Ford Field in Super Bowl XL, when the Steelers beat Seattle, 21-10. He gained 43 yards on 14 carries. “To hear the ovation from the crowd,” he said, “and to hear people I grew up with cheering for me in the Super Bowl, it was incredible. … I’m a champion, and I think The Bus’ last stop is here in Detroit.” Bettis made the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2015 — the first enshrined who was born, raised and played in the Motor City. “The experience of growing up in Detroit,” he said in his induction speech, “helped give me the character necessary to push myself as hard as I did as a football player.”

BETCHA DIDN’T KNOW: To benefit The Bus Stops Here Foundation, Bettis staged the Jerome Bettis Superbowling Extravaganza at the Majestic Theatre Center during Super Bowl XL week in February 2016, featuring music by Dwele, partying, dancing and plenty of bowling. “If you’re not averaging 200,” he said, “it’s going to be tough to beat me.”

POSITION: Running back VITALS: 5-feet-10, 205 pounds

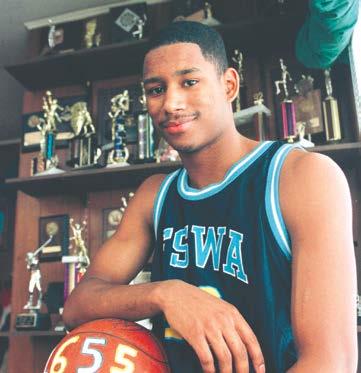

SCHOOL: Flint Southwestern YEAR: 2007

AT SOUTHWESTERN: Ingram transferred after three seasons at Grand Blanc — to move from a four-wideout to an I-formation offense — in part because “people always called me ‘son-of-former-NFL-and-Michigan-State-star Mark Ingram’” and because “I’m trying to make a name for myself.” Southwestern had never had a winning season since its 1988 opening, and even with Ingram, the Knights only finished 4-5 for the third straight season. When coach Gary Lee was suspended a game for playing two convicted felons, some Knights wanted to boycott. Ingram insisted they play — and rushed for 377 yards and six TDs on 20 carries in an 39-22 upset of unbeaten Bay City Western. His scoring runs covered 10, 65, six, 15, 16 and 59 yards; a penalty wiped out an 80-yarder. “This young man has tremendous vision,” Lee said, “and when he sees it he has tremendous explosion to the hole.” Ingram also was a terror as a defensive back.

IN COLLEGE: Ingram signed with Alabama instead of his father’s alma mater. After 728 yards and 12 TDs as a freshman backup, he posted one of college football’s great seasons as a sophomore in 2009: rushing for 1,658 yards, 6.1 a carry and 17 touchdowns; catching 32 passes for 334 yards and three TDs; and finishing with 1,992 yards from scrimmage, 20 TDs and 6.6 yards a touch. He won the Heisman Trophy over Stanford’s Toby Gerhart in the closest vote in the award’s 75 years. “My father has been a great influence on my life,” he said in the Big Apple, “and I love him to death.” Nine days from his 20th birthday, Ingram was the youngest winner, Alabama’s first winner and with USC’s Reggie Bush (2005) and Alabama’s Derrick Henry (2015) the only running backs to win this century. A month later, the Crimson Tide finished 14-0 for their first national championship since 1992 and Nick Saban’s first of five in Tuscaloosa. Ingram was the offensive MVP in the BCS title game with 116 yards and two TDs in a 37-21 victory over Texas.

HIS LEGACY: Ingram began his senior season with a Flint-record 319 rushing yards and four touchdowns against Midland Dow. He finished it with 1,699 yards on 192 carries — that’s 8.8 a pop! — and 24 touchdowns. Two years later, he found himself posing with his sport’s most famous trophy in New York’s Downtown Athletic Club — while his well-known father watched from a New York jail because of bank fraud and money laundering convictions.

IN THE PROS: Ineligible for the draft, Ingram returned for his junior season but needed knee surgery and missed the opening two games. He still gained 875 yards with 13 TDs but had only a pair of 100-yard games. In 2011, New Orleans drafted him with the 28th pick, the only back to go in the first round. After seven seasons with the Saints — highlighted by two 1,000-yard efforts and two Pro Bowls — Ingram signed with Baltimore in 2019, gained 1,018 yards and made his third Pro Bowl at age 30.

BETCHA DIDN’T KNOW: Ingram’s father, a wide receiver, also was drafted 28th — by the New York Giants in 1987.

Campy Russell

FORWARD

Pontiac Central, 1971

FORWARD

Lansing Everett, 1977 (captain)

Dan Majerle CENTER

Traverse City, 1983

Glen Rice

FORWARD

Flint Northwestern, 1985

Shane Battier

CENTER

Birmingham Detroit Country Day, 1997

Lofton Greene COACH

River Rouge, 1942-84

Terry Mills won a Class A title and Mr. Basketball with Romulus in 1986 — and three years later he won an NCAA championship with Michigan.

FIRST TEAM

Terry Mills, Romulus, 1986

Steve Smith, Detroit Pershing, 1987 (captain)

Michael Talley, Detroit Cooley, 1989

Mateen Cleaves, Flint Northern, 1996

Draymond Green, Saginaw, 2008

SECOND TEAM

Tom LaGarde, Detroit Catholic Central, 1973

Larry Fogle, Detroit Cooley, 1972

Sam Vincent, Lansing Eastern, 1981

Jalen Rose, Detroit Southwestern, 1991

Cassius Winston, U-D Jesuit, 2016 (captain)

THIRD TEAM

Jay Vincent, Lansing Eastern, 1977

Antoine Joubert, Detroit Southwestern, 1983

B.J. Armstrong, Birm. Brother Rice, 1985 (captain)

Morris Peterson, Flint Northwestern, 1995

Denzel Valentine, Lansing Sexton, 2012

In December 1996, flanked by trophies, Charlie Bell of Southwestern held the ball used to break the career scoring record for Flint schools.

FIRST TEAM

Mark Veenstra, Hud. Unity Christian, 1973 (captain)

Roy Marble, Flint Beecher, 1985

Derrick Coleman, Detroit Northern, 1986

Charlie Bell, Flint Southwestern, 1997

Drew Neitzel, Wyoming Park, 2004

SECOND TEAM

Jesse Campbell, Stockbridge, 1972

Leighton Moulton, River Rouge, 1972 (captain)

Steve Scheffler, G.R. Forest Hills Northern, 1986

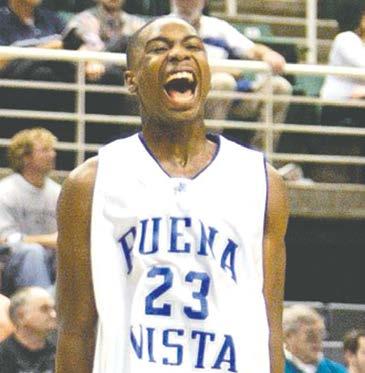

Mark Macon, Saginaw Buena Vista, 1987

Matt Steigenga, Grand Rapids South Christian, 1988

THIRD TEAM

Dirk Dunbar, Cadillac, 1972

John Wangler, Royal Oak Shrine, 1976

David Kool, G.R. South Christian, 2006 (captain)

Brad Redford, Frankenmuth, 2008

Carlos (Scooby) Johnson, Benton Harbor, 2020

As a sophomore in 2004 and a senior in 2006, point guard Tory Jackson celebrated Class C state championships with Saginaw Buena Vista.

FIRST TEAM

Mark German, Bronson, 1983

Negele Knight, Detroit DePorres, 1985

Willie Burton, Detroit DePorres, 1986

Tory Jackson, Saginaw Buena Vista, 2006

Monte Morris, Flint Beecher, 2013 (captain)

SECOND TEAM

Ron Fillmore, Sanford Meridian, 1982

Steve MacDonald, St. Ignace, 2001 (captain)

Ricardo Billings, Detroit Rogers, 2002

Brandon Cotton, Detroit DePorres, 2003

Malik Ellison, Flint Beecher, 2017

THIRD TEAM

Paul Griffin, Shelby, 1972

Brian Tolbert, Detroit DePorres, 1992 (captain)

Drew Naymick, North Muskegon, 2003

Michael Talley III, Melvindale AB&T, 2010

Jalen Terry, Flint Beecher, 2020

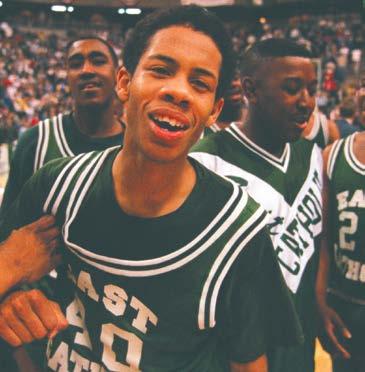

Andrew Mitchell’s three at the buzzer led Detroit East Catholic to its eighth (and last) state title in 1997 — 63-60 over Wyoming Tri-unity Christian.

FIRST TEAM

Jay Smith, Mio, 1979

Anthony Grier, Detroit East Catholic, 1981

Sander Scott, Northport, 1989

Andrew Mitchell, Detroit E. Catholic, 1997 (captain)

Jason Whitens, Powers North Central, 2017

SECOND TEAM

Tony Fuller, Detroit DePorres, 1976

Mark Kraatz, A.P. Inter-City Baptist, 1985 (captain)

Todd Lindeman, Iron Mountain North Dickinson, 1991

Bryan Foltice, Wyoming Tri-unity Christian, 1999

Michael Williams, Detroit City, 1999

THIRD TEAM

Jim Paciorek, Orchard Lake St. Mary’s, 1978 (captain)

Matt Stuck, Manton, 1992

Chris Kaman, Wyoming Tri-unity Christian, 2000

Durrell Summers, Redford Covenant, 2007

Dwaun Anderson, Suttons Bay, 2011

POSITION: Forward (captain) VITALS: 6-feet-8½, 198

HIS LEGACY: Unquestionably the greatest basketball player in state history, and arguably one of the top two or three players in NBA history. At 6-feet-9, Johnson’s ability to play guard changed the game forever. He’s among the few athletes whose skills were so amazing and his personality so dynamic that he was internationally known by a single name (a nickname at that).

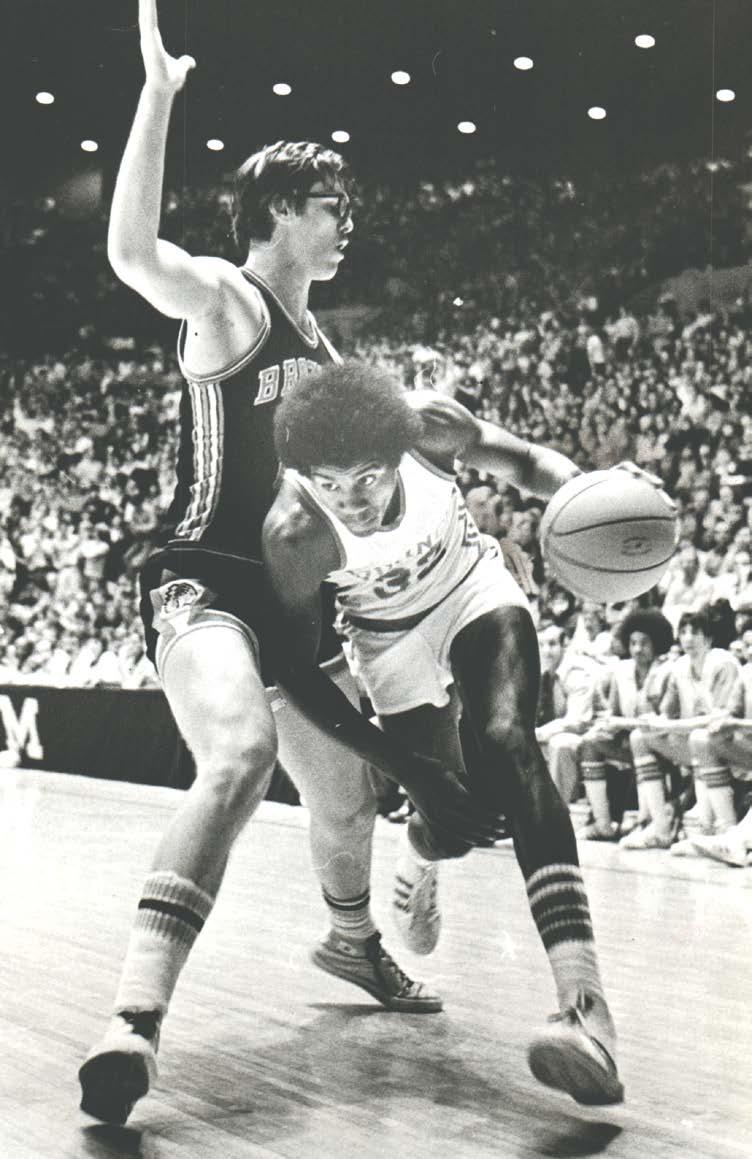

AT EVERETT: Johnson’s Vikings lost to Detroit Catholic Central in the state semifinals as a junior but won the Class A title as a senior in one of the most anticipated and exciting championship games in history — a 62-56 overtime victory against Birmingham Brother Rice. Johnson committed his third and fourth fouls in a 10-second period as the fourth quarter opened as Brother Rice built a seven-point lead. “It was my last year and my last game,” Johnson said. “And that fourth foul just made me play that much harder.” He finished with 34 points and 14 rebounds. When he finally fouled out with 66 seconds left and Everett up seven, Johnson received a rousing standing ovation in sold-out Crisler Arena. As a senior, he averaged 31.2 points and 17 rebounds. He was nicknamed “Magic” by former Lansing State Journal sportswriter

Fred Stabley Jr. early in his sophomore year.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 83

A little love tap on the arm couldn’t stop Magic Johnson from getting off his shot against Birmingham Brother Rice in the 1977 Class A championship game on March 26. Johnson’s hectic schedule after that Saturday: Thursday, McDonald’s Classic in Washington; Friday, Dapper Dan Classic in Pittsburgh; and Saturday, fly to Germany as captain of the U.S. junior national team. He returned April 17 and five days later picked the Spartans over the Wolverines: “Michigan is going to be good with or without me. Michigan State is going to be better with me. We’re going to surprise a lot of people.”

JOHN COLLIER/DETROIT FREE PRESSCONTINUED FROM PAGE 82

IN COLLEGE: Johnson chose Michigan State over Michigan and played guard for the first time in December 1977, his freshman season. He led the Jud Heathcote-coached Spartans to a pair of Big Ten titles, averaging 17.0 points, 7.9 rebounds and 7.4 assists as a freshman and 17.1 points, 7.3 rebounds and 8.4 assists as a sophomore. In 1979, MSU won its first NCAA title, 75-64, by defeating Indiana State, unbeaten and led by Larry Bird, in the most-watched championship game in history. Magic Man: 24 points, 8-for-15 from the field, 8-for-10 from the line, seven rebounds, five assists. Birdman: 19 points, 7-for21 from the field, 5-for-8 from the line, 13 rebounds, two assists.

IN THE PROS: Johnson nearly turned pro after his freshman year, but the Kansas City Kings, who held the second pick, reneged on the amount of money they said they were going to pay him. In 1979, he was the first pick of the draft by the Los Angeles Lakers, who won a coin flip with the Chicago Bulls, who had to settle for UCLA’s David Greenwood. L.A. had acquired the pick in 1976 by allowing aging Gail Goodrich to sign with the New Orleans Jazz. In 12 seasons with the Lakers, Johnson won five NBA titles, three MVP awards, three NBA Finals MVP awards and three All-Star Game MVP awards; made first-team AllNBA nine times; and was picked for the All-Star Game 12 times. In November 1991, at age 32, he retired after revealing he had tested positive for HIV. The following summer, he won Olympic gold in Barcelona with the original Dream Team. He mounted a comeback in January 1996 — averaging 14.6 points, 6.9 assists and 5.7 rebounds as a power forward — but retired again over the summer. Overall, he averaged 19.5 points, 11.1 assists and 7.2 rebounds, shot 52% from the field and 85% from the line, and played in the NBA Finals nine times. He was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame in 2002 and the Michigan Sports Hall of Fame in 1998. In retirement, he has dabbled as a coach, an executive and an owner and made millions in various business and entertainment ventures.

A QUOTE FROM MAGIC: From 1997, on his state title with Everett: “I’ve always said this was the most special championship. You were so innocent. You did it for the love of the game. You played for all these guys you knew. You knew their parents and their brothers and sisters. High school was special. I’ve got a memory like an elephant and I’ll never forget those times.”

BETCHA DIDN’T KNOW: Magic’s first nickname was “Junebug.”

In March 2015, assistants Derek Thomas and Michelle Lindsey carried coach Mary Cicerone around the Breslin Center’s court after Birmingham Marian’s sixth state championship. Thomas’ daughters, Samantha and Bailey, scored 29 of the Mustangs’ 51 points in a 14-point victory over DeWitt.

JULIAN

H. GONZALEZ/DETROIT FREE PRESS

JULIAN

H. GONZALEZ/DETROIT FREE PRESS

Teamwork makes the dream work, they say, and no teams worked together better than these 15 squads, which got the most out of stars and role players alike to ascend to the top of the Michigan prep mountain, dominating their foes along the way.

RECORD: 25-0 COACH: Larry Baker

LEGACY: The 1977 Marlins were the team that turned Farmington Hills Mercy into one of the elite programs in state history. The Marlins had lost in the previous three Class A state championship games — by one, five and 27 points — before winning the title with a perfect season. Then in 1982, after four straight titles by Flint Northern, Mercy rallied from an 18-point deficit with less than seven minutes left to play to end the Vikings’ long reign as state champs.

TOP PLAYERS: Lynn Yadach, Katie McNamara, Diane Dietz and Suzanne Brown. McNamara and Dietz played at Michigan, Brown at Central Michigan and Yadach at Oakland U.

SHAKESPEARE OF THE HARDWOOD: Baker was hired at Mercy, an all-girls Catholic school, to teach English, not coach basketball. In fact, the first girls basketball game he ever saw was the first game he coached. The trademark of Mercy basketball was its killer press. “If the press is successful, it’s a way of turning the momentum in your favor,” he said at the time. “We tend to have large crowds, and the press gets the crowd involved. It’s a way of generating offense when your half-court offense is stagnant. It creates a lot of easy baskets.”

AT LAST! After the three straight progressively more discouraging title game losses, it was far from easy when the Marlins finally broke through in 1977. Mercy trailed by 12 points in the second quarter against Detroit Mumford, out for revenge along with the state title after losing to the Marlins in the city championship game. Baker turned the tide by applying his trademark press and eventually the Marlins won by 11 points, 63-52. “I can’t believe they came back this year after last year’s humiliation when we lost, 68-41, to Marquette in the finals,” Baker said. “These kids are pretty special; they showed a lot of character, a lot of guts.” McNamara led the way with 21 points and 10 rebounds. Brown scored 15 points and Dietz added 14 points and 10 rebounds. “There was no way we were going to lose this game,” Dietz said. “I’ve played in all four of these games and winning it is the weirdest feeling. I can’t believe it. We’ve got six seniors on this team, and this makes it more of a victory for all of us.”

BETCHA DIDN’T KNOW: As the clocked ticked off the final seconds in Jenison Fieldhouse, the Marlins started singing the chorus from a song Queen released two months earlier: “We are the champions. We are the champions.”

Coach Larry Baker directed the Marlins’ senior nucleus in a drill. From the left: Suzanne Brown, Diane Dietz, Katie McNamara and Lynn Yadach. “A lot of men apologize for coaching the girls,” Baker said in 1977. “But I’ve never felt embarrassed coaching girls, especially after seeing the moves these girls have.”

LEGACY: Of the six Class A state championships won by Marian and Cicerone, the 2015 title was by far the Mustangs’ most dominant. They won their seven state tournament games by 133 points — an average of 19 points. The Mustangs also had captured the 2014 title, 44-26 over Canton.

TOP PLAYERS: Samantha Thomas, Bailey Thomas, Kara Holinski and Jaeda Robinson. Samantha Thomas played at Arizona and her sister Bailey played at West Virginia before transferring to UNLV. Holinski played at MIT and Robinson at Central Michigan.

THOMAS SISTERS: Bailey was a junior and Samantha a sophomore in the 2015 championship season. They left after the season because their father, Derek, was hired to run an AAU program in Las Vegas, and they finished their prep careers in the desert. Before assisting Cicerone for a few years, Derek Thomas had been a men’s assistant coach at Detroit Mercy and a head coach at Western Illinois. As a sophomore, Samantha Thomas made the Free Press Dream Team. “She’s just an all-around player; she does everything well,” Cicerone said. “Defensively, she can guard the other team’s best ballhandler or post player.” Bailey Thomas, meanwhile, made fourth-team Class A.

DOMINATION: The state tournament was not much of a challenge for the Mustangs, who did not lose to a team from Michigan that season. Their closest tournament game was nine points, 51-42 over Waterford Kettering in the quarterfinals. After beating DeWitt, 51-37, in the final, Holinski talked about winning the title with the Thomas sisters: “And to have these two, who are the most incredible and humblest players to be so good and to be so hard-working and so willing to help their teammates, you don’t see it that often.” Against DeWitt, Samantha had 17 points and Bailey 12.

O CAPTAIN! MY CAPTAIN! With many players in foul trouble, Holinski had to play the entire game. She scored 10 points, didn’t commit a turnover and Cicerone went on and on about her shooting ability, defense and ballhandling before shouting: “She’s Kara Holinski, my best captain ever in the world, and she got us here! She’s our leader.”

BETCHA DIDN’T KNOW: During the postgame celebration, assistant coaches Derek Thomas and Michelle Lindsey carried Cicerone on the court.

By the time Alexi Lalas visited Ford Field in 2011 to promote a soccer tournament, he had spent two decades as the country’s most recognizable player — thanks to his fierce defensive play, grungy long red hair and threeinch goatee. As a senior midfielder at Bloomfield Hills Cranbrook, his 13 goals and 10 assists earned him the Mr. Soccer Award. He also captained the state champion hockey team. At Rutgers, he won the Hermann Award, the Heisman Trophy of college futbol. In the 1990s as a defender, he was a fixture on the U.S. national team (with 96 caps), played in Italy and was in on the ground floor of Major League Soccer. He then directed MLS front offices and became a preeminent analyst on soccer broadcasts.

MANDI WRIGHT/DETROIT FREE PRESS

2019: Aidan O’Connor — Grand Rapids Forest Hills Northern

2018: Brennan Creek — Kalamazoo Hackett

2017: Michael Melaragni — Rochester Hills Stoney Creek

2016: Dalton Michael — Traverse City West

2015: Anthony Bowie — Grand Rapids Forest Hills Central

2014: DeJuan Jones — East Lansing

2013: Alec Lasinski — Ann Arbor Skyline

2012: Dewey Lewis — Rockford

2011: Zach Carroll — Grand Blanc

2010: Dzenan Catic — East Kentwood

2009: Soony Saad — Dearborn

2008: Kevin Cope — Plymouth Salem

2007: Casey Townsend — Traverse City West

2006: Casey Townsend — Traverse City West

2005: Eric Alexander — Portage Central

2004: Jake Stacy — Grand Rapids Forest Hills Central

2003: Billy Weaver — Lake Orion

2002: Simon Omekanda — Rochester Adams

2001: Ryan Alexander — U-D Jesuit

2000: J.D. Johnston — Portage Northern

1999: Ricky Strong — Rochester Adams

1998: Nick DeGraw — Clinton Township Chippewa Valley

1997: Ryan Mack — Birmingham Seaholm

1996: Corey Woolfolk — Ann Arbor Pioneer

1995: Anders Kelto — Traverse City Central

1994: Brandon Maggio — Birmingham Detroit Country Day

1993: Adam Hunter — Birmingham Detroit Country Day

1992: Tom Baker — Plymouth Salem

1991: Travis Roy — Livonia Stevenson

1990: Brian Maisonneuve — Warren De La Salle

1989: Joel Russell — Birmingham Detroit Country Day

1988: LaMarr Peters — Birmingham Brother Rice

1987: Alexi Lalas — Bloomfield Hills Cranbrook

1986: Lars Richters — Livonia Stevenson

1985: Lyle Wensley — Allen Park Inter-city Baptist

1984: Mark Noffert — Troy Athens

1983: Kanto Lulaj — Hamtramck

1982: Gary Mexicotte — Livonia Stevenson

1981: Marty Hagen — Troy Athens

1980: Nikki Gogri — Bloomfield Hills Lahser

1979: Tag Graham — Bloomfield Hills Lahser

1978: Bill Holmes — Bloomfield Hills Cranbrook

1977: Dick Huff — Birmingham Groves

1976: Tony Hermiz — Ferndale

1975: Doug Manning — Birmingham Seaholm

1974: George Poppa Jr. — Bloomfield Hills Cranbrook

In January 2010, before the Three Rivers basketball team played Richland Gull Lake, Carley Cottingham and her teammates played Apples to Apples — billed on its box as “The Game of Hilarious Comparisons!” — and enjoyed a meal prepared by Cottingham’s mother. Cottingham’s right hand was amputated in August 2009.

Midway through the first quarter, senior Carley Cottingham entered the lineup for Three Rivers. Two minutes later, she received a pass on the right wing, used an up-fake to get past a defender and drove for the first basket of her senior season.

A couple of minutes later, Cottingham drove from the left wing and converted an off-balance lay-up.

When she rejoined the game in the second quarter, Cottingham stole the ball and dribbled with her left hand before beginning a crossover move to elude a defender. But suddenly she stopped and picked up her dribble.

“I was like: ‘Crap,’” she said later. “I was so used to using both hands to fastbreak. So I just had to pick the ball up and wait for someone to come back to me.”

Cottingham no longer could use both hands to dribble … or shoot … or tie her shoes … or put her long light brown hair in a ponytail … or do any of the things she did for the first 17 years of her life.

Why? Because of the answer to a question she gave Aug. 26, 2009, at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit.

It was early that morning when a nurse at the door of an operating room asked Cottingham the question: “What are we going to do today?”

Cottingham glanced at her right hand and looked at Dr. Donna Tepper, a plastic surgeon. Tepper nodded and Cottingham said: “They’re going to take it off.”

Cottingham was back in her hospital room a few hours after having her right hand — her dominant hand — amputated at the wrist when she first realized the ramifications.

Her father, Chad, mentioned basketball.

“I started thinking: ‘How am I supposed to play? How do I shoot?’” she re-

Three Rivers guard Carley Cottingham had no intention of missing her senior season despite losing her right hand over the summer to thoracic outlet syndrome. She missed only three games.

called. “And then he said I’d have to be left-handed. I said: ‘I don’t want to be left-handed.’

“I used to mess around and say I

was going to write my name left-handed. Now I’m stuck.”

From the moment she left the operating room, Cottingham had to do everything left-handed.

But four months after the amputation, Cottingham was playing again for Three Rivers and acting exactly like the amazing, fun-loving, self-effacing teenager she was before she lost her hand. The doctors couldn’t save the hand, but they saved the patient — mentally and emotionally.

Cottingham became left-handed because she had two extra ribs at the top of each rib cage, just below her collarbone, and wound up suffering from thoracic outlet syndrome.

“There’s a little window where all the arteries and veins go through,” said her father, a middle school principal in Three Rivers, located in southwestern Michigan near Kalamazoo. “Well, the extra rib made it pinch, so the pinching was causing clots and then the heart would beat faster and — boom! — it would blow those clots and they