Local Gardener Canada’s

Canada’s Local Gardener brief readers survey

From time to time, we like to find out who is reading our magazines so that we can make sure we can include the best information that is relevant to you.

You can fill out this survey and mail it in or you can access it online at https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/HB2776R.

Thank you for giving us a hand by answering a few questions! q

1. What kind of plants do you grow? Check all that apply.

Ornamental annuals and perennials

Fruits and vegetables

Herbs

Houseplants

Trees and shrubs

Water plants

2. Which articles do you enjoy reading? Check all that apply.

Flower profiles

Vegetable profiles

Herb profiles

Garden profiles

Ideas in gardening

Design

Insects and animals

Plant diseases

Projects

3. Are there any that you prefer not to see?

6. Do you live in an urban, suburban or rural area?

Urban

Suburban

Rural

7. What province do you live in?

British Columbia

Alberta

Saskatchewan

Manitoba

Ontario

Quebec

New Brunswick

Nova Scotia

Prince Edward Island

Newfoundland and Labrador

Other

8. What is your age?

30 and under

31 to 40

41 to 50

51 to 60

61 to 70

71 and over

4. How long have you been gardening?

Less than 1 year

1 to 5 years

6 to 15 years

More than 15 years

5. In which format do you read Canada’s Local Gardener?

Digital

Both

Mail your hard copy of the completed survey to:

Pegasus Publications Inc. PO Box 47040, RPO Marion, Winnipeg, Manitoba R2H 3G9

9. Are there any other topics you would like to see covered in Canada’s Local Gardener?

Or complete the survey online at: https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/HB2776R

How to access bonus editorial features

Find additional content online with your smartphone or tablet whenever you spot a QR code accompanying an article. Scan the QR code where you see it throughout the magazine. Enjoy the video, picture or article! Alternatively, you can type in the url beneath the QR code.

Follow us online www.localgardener.net

Facebook: @CanadaLocalGardener

Instagram: @local_gardener

YouTube: @LocalGardenerLiving

Published by Pegasus Publications Inc.

President Dorothy Dobbie dorothy@pegasuspublications.net

Editor & Publisher Shauna Dobbie shauna@pegasuspublications.net

Art Direction & Layout

Karl Thomsen karl@pegasuspublications.net

Contributors

Elaine Arsenault, Holly Burke, Dorothy Dobbie, Shauna Dobbie, Caroline Fu, Robert Pavlis, Tania Scott and Pam Stewart.

Editorial Advisory Board

Greg Auton, John Barrett, Todd Boland, Darryl Cheng, Ben Cullen, Mario Doiron, Michel Gauthier, Mathieu Hodgson, Jan Pedersen, Stephanie Rose, Michael Rosen, Aldona Satterthwaite and Trudy Watt.

P rint Advertising

Gord Gage • 204-940-2701 gord.gage@pegasuspublications.net

Marketing Manager Micaela Soto • 204-940-2702 micaela@pegasuspublications.net

Subscriptions

Write, email or call Canada’s Local Gardener P.O. Box 47040, RPO Marion Winnipeg, MB R2H 3G9 Phone: 204-940-2700 info@pegasuspublications.net

One year (four issues): $35.85

Two years (eight issues): $68.08

Three years (twelve issues): $98.40

Single copy: $12.95 Plus applicable taxes.

Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to: Circulation Department

Pegasus Publications Inc. PO Box 47040, RPO Marion Winnipeg, MB R2H 3G9

Canadian Publications mail product Sales agreement #40027604 ISSN 2563-6391

CANADA’S LOCAL GARDENER is published four times annually by Pegasus Publications Inc. It is regularly available to purchase at newsstands and retail locations throughout Canada or by subscription. Visa, MasterCard and American Express accepted. Publisher buys all editorial rights and reserves the right to republish any material purchased. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited without permission in writing from the publisher.

Copyright Pegasus Publications Inc.

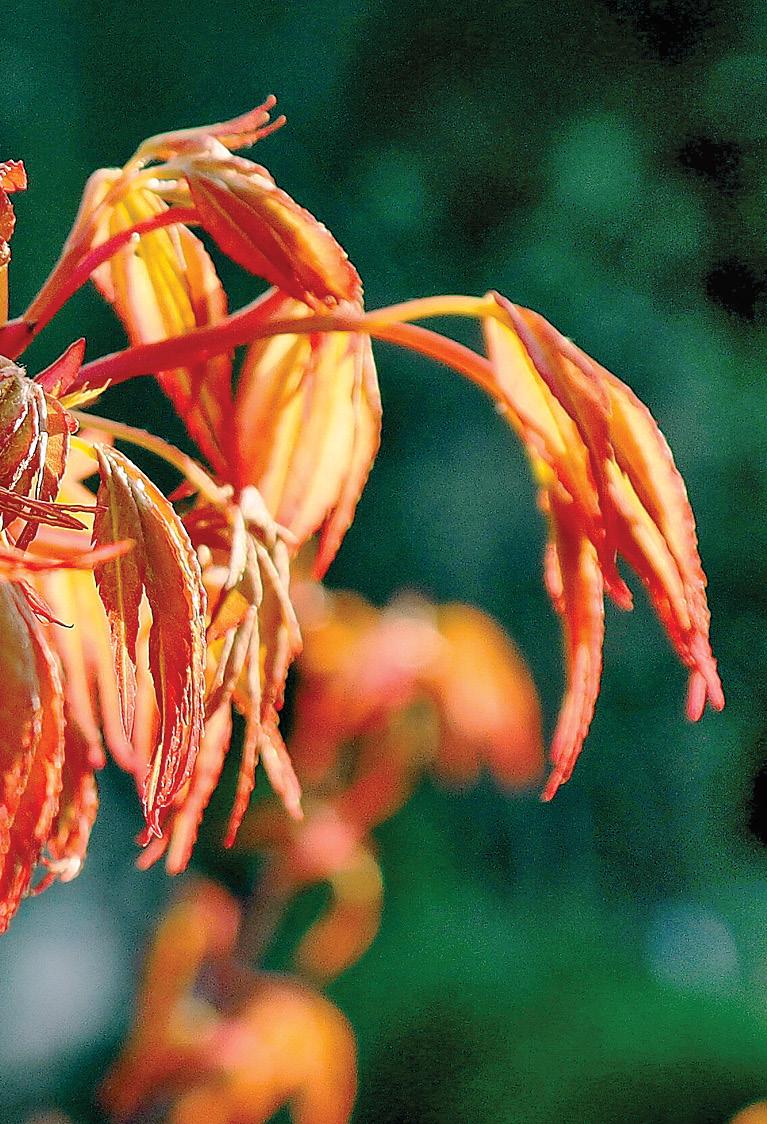

Also considered for the cover...

Yellow for fall with bright blooming heliopsis won the day when we were choosing the cover.

These pictures were all taken by Shauna Dobbie during a trip to the International Peace Garden near Boissevaine, Manitoba, in August. The Garden offers plenty of gorgeous vistas of flowers, which is perfect for Canada’s Local Gardener’s overall aim of inspiration for people at home.

The picture with yarrow, left, seems too pink for fall. The golden rod, below that, is a perfect lateseason flower, but both of these two pictures lack definition. The oxeye daisies, right, have some definition, and we could make the gap without blooms look better with words (“slugs”); in the end, it just left us all feeling kind of blah.

Creamy coloured lilies, upper left, make an excellent picture, but we are trying to offer covers with whole gardens rather than specimen shots. Still, this one could win the day for our next issue. q

See the piece on page 9 for a couple of fun facts about heliopsis.

Response of plants to wildfire smoke

When wildfire smoke fills the air, we retreat indoors to avoid inhaling harmful particles and gases. But what about the plants that remain outside? Research reveals that trees and other plants react to smoky conditions in ways that closely mirror human behavior – they too can "shut their windows" to protect themselves.

Plants breathe through stomata, tiny pores on their leaves, absorbing carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen. These pores also allow for the exchange of other gases, which can include pollutants from wildfire smoke. Early 20th-century studies observed clogged stomata in trees exposed to pollution, hinting at the adverse effects of environmental contaminants on plant respiration.

Recent research into the effects of wildfire smoke on plants has shown mixed results. Some field studies suggest that smoke might enhance photosynthesis by scattering sunlight, while laboratory studies indicate a

decline in plant productivity after smoke exposure, although plants recover after a few hours.

During a US field study during the 2020 wildfire season in Colorado's Rocky Mountains, scientists observed Ponderosa pines reacting to dense smoke by closing their stomata, effectively halting photosynthesis. This protective response suggests that plants can regulate their gas exchange as a defense mechanism against smoke.

Further experimentation showed that lowering smoke could temporarily

Improve your harvest with Seaweed Magic

Seaweed Magic is more than just a fertilizer. Made in Canada from seaweed harvested from the icy waters of Canada’s Atlantic coast, one 15 g packet gives you 125 litres of goodness you can use on your vegetables, flowers and houseplants, indoors and out. You can stock up on Seaweed Magic from Canada’s Local Gardener! 15 g for $12.95. Scan the link below or visit our webstore at localgardener.net

restore photosynthesis, indicating that plants may employ multiple strategies to cope with smoke, such as preemptively closing stomata or physically blocking them with smoke particles.

This adaptive behavior highlights the resilience of plants, yet the longterm effects of repeated wildfire smoke exposure remain unclear. As wildfires become more frequent due to climate change and human activities, understanding these responses is crucial for forest management and conservation efforts. q

Colourized electron microscope image of a stomata on the leaf of a tomato plant.

Photo by Greg Hume.

Photo by Photohound.

Norway spruce needles are dotted with white – showing the stomatas.

New All-American Selections for 2025

Abeautiful new annual (or perennial above zone 7), Dianthus ‘Capitán Magnifica’ from Ball Seeds, will bloom all summer, no matter how hot it gets. Give it a chop after blooming the first time and it will reward you with a bounty of new deep pink blooms with pretty picotee edging. The stems are long enough to cut

for indoor bouquets, too. And the more you cut for bouquets, the more flowers will bloom!

The AAS has also named some new colours from the nasturtium ‘Baby’ series, from American Takii, for the honour. Tropaeolum minum ‘Baby Gold’, ‘Baby Red’ and ‘Baby Yellow’ join ‘Baby Rose’. The plants are known for being a petite

and floriferous mounding variety with dark green foliage.

Rounding out the announcement is a new zinnia from Syngenta, Zinnia x marylandica ‘Zydeco Fire’. Double zinnias that are bigger than others on sturdy stems last from bloom right up until frost, and foliage is disease resistant. q

helps you stay connected to those who matter most,

Dianthus ‘Capitán Magnifica’.

Zinnia x marylandica ‘Zydeco Fire’.

Nasturtium ‘Baby Gold’.

Nasturtium ‘Baby Red’. Photos

Certify your garden at the Canadian Wildlife Federation

We love seeing birds and butterflies grace our gardens, delighting us with their song, colours and comical antics. And they play a critical role in pollinating our food, being a food source for other animals and controlling potential pest species. But gardeners also have the powerful opportunity to help them. With the simple everyday choices for enhancing or maintaining your garden, you have the power to tip the scales in helping our wild neighbours, and ultimately ourselves, thrive.

This is good news, but it gets even better! Gardening with wildlife in mind is so versatile that it can be tailored to any budget, property size or lifestyle. There are four main components, three of which are including habitat elements – water, food and shelter. The fourth is avoiding pesticides. Examples of water are

a pond with a shallow area or a shallow dish of water in the warmer months. Natural sources of food are easily supplied by growing a variety of native and other beneficial plants, from trees and/or shrubs to perennials. Shelter is also provided through these plants as well with many other natural features such as allowing some leaves to remain under trees where possible. Now you have a vibrant garden space that attracts and supports your wild allies, it is imperative that their food, and they themselves, are not poisoned with pesticides.

bee species and toads. The Canadian Wildlife Federation (CWF) celebrates these efforts by providing Garden Habitat Certification where your property receives “Wildlife-friendly Habitat” designation. Successful applicants are also eligible to purchase either a brushed metal or coloured sign which recognizes their efforts and can raise awareness in the community.

By doing so you have the satisfaction of knowing you are helping our local and migratory wildlife, from monarch butterflies to chickadees, endangered

CWF has a myriad of resources to help Canadians enhance their outdoor space from webinars and an online course to posters, handouts, a Native Plant Encyclopedia and more. They also have lots of information on our local and migratory wildlife and the plants they rely on. Visit GardeningForWildlife.ca to find out more. q

Get certified!

Plant some heliopsis

Heliopsis, often known as false sunflower, is a vibrant and resilient perennial that's native to the Americas. It’s hardy to zone 3 and loves plenty of sun, the more the better.

Despite its common name, it isn't closely related to true sunflowers (Helianthus species) but resembles them in appearance. This makes it a fantastic substitute in gardens where true sunflowers might be too large or aggressive.

Heliopsis plants are also known for their ability to thrive in poor soil conditions and tolerate drought once established, making them a low-maintenance choice for gardeners looking to add long-lasting colour to their landscape. They bloom from early summer to fall, providing bright, cheerful yellow or orange flowers that attract a variety of pollinators such as bees and butterflies. q

Hort Expo in China

The Canadian Nursery Landscape Association (CNLA) recently attended the International Horticultural Expo in Chengdu, China. This event is a showcase for Chengdu’s booming horticultural scene, drawing in experts and media from eight countries.

Set over 128 hectares, the Expo celebrates Sichuan’s rich culture with a theme of “The Park City”, demonstrating Chengdu’s knack for blending nature with urban living. Think green highways and quieter, prettier cityscapes.

The Expo, that ran until the end of October, offers a mix of indoor and outdoor activities ranging from gardening to arts and tech in horticulture. It’s a place for learning, playing, and exploring innovative garden designs that marry the old with the new.

There’s also a special spot in a beautiful area of the city, Pidu, known for its deep history in floriculture dating back over 3000 years. Here, visitors can marvel at the Flower Cube, which exhibits stunning floral arrangements from around the globe and highlights the local tradition of bonsai and orchid cultivation.

Chengdu, famed for its pandas,

is now gaining recognition for its role in global horticulture, aligning with efforts to integrate nature into daily urban life. The Expo itself is a visual feast, featuring designs inspired by plant life and offering a blend of hospitality, serene gardens, and vivid floral displays.

It was an honour for the CNLA to experience and help promote such an inspiring event. If you’re up for exploring ancient bonsai, tranquil gardens, and great food, Chengdu’s Horticultural Expo is not to be missed. Come see why it’s a top-tier event in one of the world’s loveliest regions. q

International Horticultural Exhibition 2024 Chengdu that ran from April 26 to October 28, 2024.

Zinnias

Story by Dorothy Dobbie

When we first create a new garden, it is hard to achieve all those beautiful blooms you are dreaming about in the early days. It takes time for perennials to reach their maximum blooming capacity, and some will remain stubbornly unflowering for two or three years as they acclimatize to local conditions. You are also still waiting to learn just how much to add as the new transplants develop into their final clump size.

One simple answer to the colour and space dilemma is to plant annuals, and one of the most rewarding of those is zinnia (Zinnia elegans). Zinnia are brilliantly coloured, come in all sizes, bloom all summer and are easy to grow from seed, saving the frugal gardener much added expense.

If you are looking for early colour, sow the seeds indoors about a month to six weeks before the last frost. Transplant outside after hardening them off (introducing them to the great outdoors a little at a time) in soil that has reached about 21 Celsius and you know that the last frost date has passed. It takes about 70 days from germination to blossom.

Much simpler is to buy seedlings started by your local garden centre, although they sometimes resent being transplanted.

Remember, even though zinnia is a native to southern North America and Mexico, these are tender annuals that will not resow themselves in Canada as would cosmos, for example.

The word zinnia comes from a German botanist, Gottfried Zinn, who made this gift to the botani-

cal world in 1759. They symbolize the thoughts of absent friends. The Aztecs loved zinnias and called them “plants that are hard on your eyes”. No wonder! Zinnias are brilliantly coloured in stunningly bright pinks, yellows, reds, oranges, peaches, purples, limes and white. There is even a deep, dark, blue one and some hybrids are multi-coloured.

You can plant zinnias directly into the ground or grow them in pots. Hybridizers have had fun with these flowers for the past 250 years so there are many choices. Stick the shorter varieties into containers and leave the tall ‘State Fair’ or ‘Benary Giants’ (that can get to four feet tall) for in-ground planting. But the choices are endless from there with all sorts of sizes down to ‘Thumbelina’ which is only 6 to 8 inches in height. Blossoms can be single, semidouble, double and some even come in cactus types.

Whatever variety you choose, be sure to keep them deadheaded to encourage endless blooming. They also need a steady diet of water to keep soil evenly moist (not wet) and lots of sunlight, six to eight hours a day. They like rich, well-composted soil with good drainage.

Zinnias make a very good cut flower lasting a week or more in a vase. Butterflies love them and their seeds are desirable food for local bird populations. And as a bonus, they are deer resistant!

Watch out for powdery mildew (plant them far enough apart to encourage air circulation). Now, sit back and enjoy their brilliance. You won’t be missing those perennials at all! q

‘Thumbelina’ zinnia.

Image courtesy of Ball Horticultural Company.

‘State Fair’ zinnia.

Image courtesy of Ball Horticultural Company.

Growing corn

Story by Shauna Dobbie

Every year in the fall, I’m sorry that I didn’t plant corn. Then in the spring, it feels like there just isn’t space for it. Here is what I need to know to do it next year.

Choosing the right corn variety

Presuming you want to grow “sweet” corn for fresh eating – there are also “flint”, for flour, and “popcorn” – look for an early-maturing type. ‘Peaches and Cream’ has been a favourite since it was introduced in the 1970s, but you can try, among others, ‘Allure’, ‘Montauk’ or ‘Raquel’. Each matures in under 80 days.

Planting corn

Give corn the sunniest area you can. This is not a vegetable to experiment with under a tree.

Wait until the soil has warmed up. It must be at least 21 Celsius for corn to germinate. Test the soil for temperature (you can use an instant read thermometer for cooking as long as it will read down to freezing). Seeds often rot before they germinate if planted in cold soil. If it rains and you don’t see sprouts in a couple of days, replant.

Soil preparation. Corn thrives in fertile soil rich in organic matter. Amend your soil with compost or well-

rotted manure in early spring. Aim for a pH of 6.0 to 6.8.

Sowing seeds. Plant corn directly into the ground after all danger of frost has passed, usually in late May to early June. Corn seeds should be planted about 1 inch deep and spaced 8 to 12 inches apart. It is wind-pollinated, so plant it in blocks rather than single rows to ensure good pollination. A small patch with at least 4 rows, each 3 feet apart, will improve pollination success.

Corn seeds last only about two years, so consider buying fresh seeds every year.

Watering and fertilizing. Corn is a heavy feeder. Keep the soil consistently moist and apply a balanced fertilizer, such as 10-10-10, when plants are about 12 inches tall, and again when tassels appear.

Pollinating corn

Plant as a block. As stated above, resist the urge to plant a row of corn. Instead plant it as a block: rather than 12 in a row, plant it in three shorter rows with four plants each.

Keep the garden wind friendly. Since corn relies on wind for pollination, ensure there’s some airflow through your garden. If you have barriers like solid

For many, fresh corn is the highlight of the summer harvest season.

fences or tall hedges, consider trimming them back or planting your corn in a more open space to allow wind to carry pollen through your corn patch.

Hand pollinating. For small gardens, hand pollination is a great way to ensure every ear of corn is pollinated fully. The tassels (the pollen producing flowers at the top of the plant) typically open about a week before the silks emerge. Once the silks emerge, gently shake the tassels above them.

Harvesting corn

Corn is typically ready to harvest about 18 to 24 days after the silk appears. The best way to tell if your corn is ripe is by checking the kernels. Pull back a small section of the husk and press your thumbnail into a kernel. If a milky liquid squirts out, the corn is ready to pick. If the liquid is watery, give it more time. If the liquid is thick

When you browse seed catalogs for corn varieties, you may notice letters like SU, SE, SH2, or SY listed after the variety names. These letters refer to the type of sweet corn and its genetic traits, particularly how sweet the kernels will be and how long they can be stored after harvesting. Here’s what they are.

• SU (sugary). This is the standard or traditional variety of sweet corn. SU types have lower sugar content and a creamy, old-fashioned

or doughy, the corn is past its prime.

Harvest your corn in the morning for the best flavour, and eat or preserve it as soon as possible, as the sugars begin converting to starch after picking.

Common problems

Nitrogen deficiency. Corn is sensitive to nitrogen levels. The leaves may turn yellow, especially the lower leaves, indicating a deficiency.

Other deficiencies. Poor soil fertility can also lead to issues like phosphorus or potassium deficiency, which will manifest as poor growth or weak plants.

Corn earworm. These caterpillars bore into the tip of the corn ear, feeding on kernels. To manage them, consider applying a few drops of mineral oil to the silk after pollination to deter egg-laying, or use biological controls like Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt). Ask for it at your

Alphabet corn

flavour. However, they must be eaten soon after harvest, as the sugars convert to starch quickly.

• SE (sugar-enhanced). SE varieties are sweeter than SU types and hold their sweetness for longer after picking. This makes them more forgiving for home gardeners, as you don’t have to rush to eat or preserve them immediately. SE corn has tender kernels and a more modern sweet flavour.

• SH2 (supersweet). These varieties have a much higher sugar content

than SU or SE types and maintain their sweetness for several days after harvest. SH2 corn is often used for freezing or long-term storage but can have crisper texture than SE types.

• SY (synergistic). SY varieties combine traits from multiple types of corn, often mixing SE and SH2 genetics to give you the best of both worlds: sweet flavour, tender texture, and good storage life. On the downside, it is a little pickier about growing than the other types, requiring perfect conditions.

Corn benefits from being planted in blocks rather than rows.

Season extension tips

For those in cooler regions of Canada, extending the growing season is crucial. Here are a few ways to help corn thrive in shorter summers.

• Start indoors. Corn doesn’t transplant well, but if your growing season is short, you can start seeds indoors in biodegradable pots and transplant them once the soil is warm.

• Use plastic mulch. Applying black plastic mulch around your corn plants helps to retain soil moisture and keeps the soil warm, promoting faster growth in cooler areas. Make sure you spend time watering your corn, making sure to target the hole in the plastic, since the mulch prevents water from getting to the roots.

• Row covers. Early in the season, clear plastic row covers can trap heat and protect young corn seedlings from cold nights or late frosts.

Corn smut

Corn smut, also known as Ustilago maydis, is a fungal disease that affects corn plants. It causes grayish-black galls to form on the kernels, leaves, and stalks. While often seen as a destructive pathogen in conventional agriculture, it has a fascinating dual identity. For farmers focused on selling flawless ears of corn, the presence of these galls can result in unsellable crops, but in certain parts of the world, this same fungus is considered a culinary treasure.

In Mexican cuisine, corn smut is highly prized and known as huitlacoche – sometimes referred to as “Mexican truffle”. Huitlacoche is harvested when the smut-infected kernels are still young and tender, before they mature and turn black. Once cooked, it transforms into a delicacy with a rich, earthy, and slightly smoky flavour similar to mushrooms. It is commonly used in tacos, quesadillas, and soups, and is becoming increasingly popular with food enthusiasts beyond Mexico.

For those interested in trying huitlacoche, it must be cooked to enhance its flavour and texture. When sautéed with onions, garlic, and spices, it adds a unique depth to dishes. Although corn smut is often considered a problem for gardeners and farmers, its reputation as a gourmet ingredient shows that even a crop disease can have a silver lining, depending on how you look at it.

garden centre if you aren’t familiar.

European corn borer. This pest tunnels into the stalk, weakening the plant. Keep your garden clean of debris where larvae may overwinter, and rotate crops yearly to reduce infestations.

Aphids. These small, sap-sucking insects can weaken plants and attract ants. Aphids can be managed by spraying a strong jet of water on the plants or by introducing beneficial insects like ladybugs.

Common diseases. Corn can suffer from rust (small, orange pustules on leaves). Remove infected plants immediately to prevent the spread of disease. Crop rotation also helps reduce the occurrence of these diseases.

Corn smut. You can control this by removing infected plants as soon as you see it, or you can grow it as a delicacy; see the sidebar.

Dealing with animals

Corn is a magnet for various birds, raccoons, and squirrels.

Birds. Crows and blackbirds are notorious for pulling up young corn seedlings. Use row covers or netting early in the season to protect your seedlings.

Raccoons. These nocturnal creatures love to raid corn patches just before harvest. Consider installing an electric fence (start by checking if it’s legal in your area) or use motion-activated lights or sprinklers to deter them. Honestly? If you have raccoons in your yard regularly, you may want to consider planting something else.

Squirrels. They may nibble on ears of corn. A combination of fencing and repellents, such as cayenne pepper sprays, can help reduce their activity. q

Corn is typically ready to harvest about 18 to 24 days after the silk appears.

Photo by Idéalités.

Fresh huitlacoche is a high-end gastronomic product in Mexico.

Biodynamic gardening

Story by Shauna Dobbie

Biodynamic gardening encourages a greater awareness of the Earth’s natural cycles – such as the cycles of the moon.

Biodynamic gardening, while often lumped in with organic practices, comes with its fair share of eccentricities. Originating from the ideas of Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner, who was searching for a synthesis between science and spirituality in the early 1900s, it mixes practical farming methods with a heavy dose of mysticism. For Canadian gardeners who are serious about sustainability, there’s a lot to appreciate in the emphasis on soil health and ecological balance. But some of the more esoteric aspects of biodynamic gardening – like planting according to lunar cycles and preparing cow horns filled with manure to bury in the ground – can seem a bit far-fetched.

At its core, biodynamic gardening does offer useful principles, particularly when it comes to soil management. Like organic gardening, it focuses on creating a healthy, self-sustaining ecosystem in which plants, soil, and animals all work together. Composting is essential, and biodynamic practitioners take it a step further by using herbal preparations made from plants like yarrow, chamomile, and valerian to ‘enrich’ the compost. These herbal additives supposedly enhance the compost’s ability to foster healthy soil, but the ritualistic way they’re prepared and applied – timed to the stars and moon – might raise some eyebrows among gardeners who prefer more straightforward methods.

Then there’s the biodynamic calendar, which guides planting, weeding, and harvesting based on the phases of the moon and the position of the zodiac constellations. The idea is that certain days are better for certain gardening tasks – root vegetables are planted on "root days," flowering plants on "flower days," and so on. While it’s tempting to see this as little more than a fanciful notion, biodynamic gardeners insist that working with these cycles improves crop yields and plant health. To the practical gardener,

Biodynamic agriculture is an alternative agricultural practice initially developed in 1924 by Rudolf Steiner (above).

though, success might have more to do with the attention to detail and careful planning that biodynamic gardeners inevitably apply, rather than the waxing or waning of the moon.

One of the more eyebrow-raising practices is the horn manure preparation, known as “500”. This involves stuffing a cow horn with manure, burying it in the soil through the winter, and then digging it up in the spring. The decomposed manure is then diluted in water and sprayed over the garden, with the claim that it enhances the soil's vitality. To skeptics, this might sound more like a strange ritual than a legitimate gardening technique. Still, biodynamic gardeners swear by it, and there’s no denying that focusing on soil quality is a pillar of any successful gardening approach, whether you’re into cow horns or not.

For Canadian gardeners, especially those in harsher climates, biodynamic gardening's emphasis on healthy soil, biodiversity, and ecological awareness makes sense. It aligns with broader trends towards sustainability and regenerative practices, which aim to not just minimize harm but actively improve the land. The more mystical elements – like reading the stars for when to plant your tomatoes – can easily be left by the wayside without compromising the real benefits of biodynamic gardening.

While some may find value in the cosmic aspects of biodynamics, it’s clear that much of the success in this method comes from a dedication to observing the environment and nurturing soil health. For gardeners who want to embrace a thoughtful, eco-friendly approach without buying into the more far-fetched ideas, there’s still plenty to take away from biodynamics. You don’t need a celestial guidebook to know that healthy soil and diversity in the garden will always lead to a flourishing garden. Whether or not you bury a cow horn filled with manure is up to you. q

Longkeeper tomatoes to extend the season

Story by Tania Scott

Longkeeper tomatoes are a great way to extend the gardening season in Canada. Longkeepers are a type of storage tomato that are meant to be picked unripe at the end of the season, and then stored for weeks or even months in a cool, dry place. Although not well known to Canadian gardeners, longkeepers have a long history in Spain and Italy, and are a part of the food heritage in these countries.

Considering our short growing season, longkeepers are a great choice for Canadian gardeners. Not only is it a wonderful feeling to eat tomatoes from your garden in December, especially when you look out the window and see your garden is covered in snow, but it is also a very practical thing to do, when you consider the price of tomatoes in December. Think of longkeepers as the future of food security.

How to grow longkeepers

Longkeepers don’t have any special growing instructions compared to other types of tomatoes. I start longkeepers indoors at the same time I start my regular tomato seeds (4 to 6 weeks before the last frost). I plant 2 or 3 seeds per container ¼ inch deep. When the seedlings are up, I move the pot into a sunny spot or under lights and then transplant the seedlings into a larger container when the plant’s true leaves appear. At the end of May, I transplant my seedlings outside (after the danger of frost has passed).

How to harvest, store and use longkeepers

At the end of summer, your longkeepers will probably be unripe and green, which is exactly what you want. A few may have turned their ripe colour, which is fine; you can enjoy them a bit earlier. Pick your longkeepers before the first frost and store them.

In their classic how-to book, Root Cellaring, food storage experts Mike and Nancy Bubel suggest storing longkeeper tomatoes at 13° to 18° Celsius to keep them on hold for a while. This likely means a spot in your basement or a colder room in your house. Place the longkeepers in a single layer in a cardboard box or on a shelf out of direct sunlight.

The Bubels also suggest you can store longkeepers on your kitchen counter at room temperature (15° to 21°

There’s nothing better than tomatoes off the vine, but there are some special longkeeper varieties that let you savour fresh tomatoes after you put the garden to rest.

Celsius), but this will speed up the ripening process. Keep it simple and do whatever works for you. Use longkeepers for fresh-eating (see the recipe for Pa am oli below) or in cooked dishes such as soups, stews, and sauces.

Longkeeper tomato varieties

‘Giallo a Grappoli’. This is a beautiful longkeeper from Italy. Pick ‘Giallo a Grappoli’ at the end of the summer when its ping-pong ball sized fruits are green or light yellow. Over the next few months, its skin will turn golden yellow when ripe and its internal colour will be a beautiful peachy-pink.

‘Piennolo Giallo del Vesuvio’, also known as ‘Giagiu’. This is the yellow version of the famous Italian heirloom ‘Piennolo del Vesuvio’. Translated from Italian it means, ‘Yellow Piennolo tomato grown in the Vesuvius area’. This Italian variety is traditionally used as a storage variety for winter tomatoes, but we also enjoy the cherry tomatoes in summer, as they can ripen early. The tall plants produce large clusters of mildly sweet, oval-shaped cherry tomatoes.

‘Golden Treasure’. This wonderful, beefsteak-size longkeeper is a Tim Peters’ variety. Tim Peters is a master American tomato breeder who created several excellent storage varieties. This is how Tim described ‘Golden Treasure’ in the 1999 Garden Seed Inventory:

“The first long-keeping tomato with gold skin colour, ripens from green to golden and can keep for up to four months. Vigorous indeterminate vines, fruits 70 g to 115 g [2.5 to 4 ounces], acidic tomato flavour becomes more mild in storage.”

‘Golden Treasure’ will turn golden yellow when ripe and feel firm.

‘Winter Gold’. This is another excellent longkeeper from the tomato breeder Tim Peters. Keep your eyes open for tomatoes developed by this master American breeder from Oregon. The plants are a compact 1 foot in height and do well in a container. They have dark green, rugose leaves and medium-to-large size tomatoes. ‘Winter Gold’ will turn yellow when ripe and feel firm.

Ramallet. Ramallet tomatoes are a type of longkeeper grown on the island of Majorca, Spain. They are listed on the Ark of Taste, a world catalog of significant heritage varieties of vegetables, animals and food products. There are several varieties of ramallet tomatoes, usually named after the region where they are grown, for instance, the tomato ‘Ramallet Sant Llorenc’ comes from the village of Sant Llorenc on Majorca. Ramallet tomatoes are generally small-to-medium size red-orange tomatoes with thick skin and good, higher acid taste.

In Majorca, ramallet tomatoes are hung in bunches to use over the winter. Traditionally, they are used in a dish called pa am oli (translated as ‘bread and oil’ from the Mallorquin language), which is described on the Ark of Taste website as: “a slice of toast with a drizzle of oil on which the tomato is crushed. Sometimes, it is also accompanied by Jamon Serrano [ham], cheese, local olives and pickles.” q

Tania Scott is a seed saver and urban farmer. Tania and her family love growing things and have started the seed company Common Sense Seeds (www.commonsenseseeds.ca) in Calgary. Ramallet tomatoes.

‘Giallo a Grappoli’ tomatoes.

‘Golden Treasure’ tomatoes.

Photo courtesy of Tania Scott.

Photo courtesy of Tania Scott.

Photo by Rotget.

7 Japanese maples and alternatives

Story by Shauna Dobbie

The beautiful Japanese maple, Acer palmatum, is a goal for gardeners in zones 5 and above and a dream for gardeners in zones 2, 3 and 4.

Japanese maples are prized for their elegant, graceful form and variously textured foliage, from finely cut leaves to small fat hands in perfect symmetry. The leaves come in a range of colours, from deep reds and purples to vibrant greens, with many varieties showcasing dramatic colour changes in the fall. Some varieties also have interesting bark, like the coral bark maple, which adds year-round visual interest. And they all stay a manageable size, none getting taller than 25 feet.

Here are some Japanese maples that are deservedly popular.

‘Bloodgood’ typically grows 15 to 20 feet tall. This is one of the most popular Japanese maples, featuring deep red-purple leaves that hold their colour throughout the summer before turning bright crimson in the fall. It forms a rounded canopy and has smooth, dark gray bark, making it ideal for medium-sized landscapes.

‘Crimson Queen’ reaches a height of 8 to 10 feet. It is a weeping, lace-leaf variety with finely cut, rich red

foliage. The leaves retain their colour well during the growing season and turn bright crimson in the fall. Its cascading form is perfect for smaller gardens or containers, adding a delicate texture to the landscape.

‘Sango Kaku’ (coral bark maple) grows to about 20 to 25 feet tall. This tree is famous for its striking coralcoloured bark, which intensifies in winter. The light green leaves emerge in spring and transform into yellowgold in the fall, providing multi-season interest. It’s a fantastic choice for adding winter colour to the garden.

‘Tamukeyama’ typically reaches 6 to 8 feet in height. This cascading variety has deep purple-red leaves that retain their rich colour well throughout the season. In the fall, the foliage turns a brilliant scarlet. The fine, lace-like leaves and elegant form make it an excellent focal point in a small garden.

‘Shishigashira’ (lion’s head maple) grows 10 to 15 feet tall. It has curled, deep green leaves that are densely packed, giving the tree a compact and upright form. In autumn, the leaves turn golden-orange, providing a stunning seasonal display. Its unusual growth habit makes it a standout in any landscape.

Acer palmatum ‘Bloodgood’.

Acer palmatum ‘Katsura’.

Photo by

Johnathan Billinger.

‘Emperor 1’ typically grows to about 15 to 20 feet in height. This cultivar is similar to ‘Bloodgood’ but leafs out later in the spring, reducing the risk of frost damage. The dark red leaves turn a vibrant crimson in fall, and its upright form makes it suitable for a variety of garden settings.

‘Katsura’ reaches a height of 10 to 12 feet. It is known for its early leafing, with the new foliage emerging in shades of orange and yellow in the spring. The leaves transition to green in summer, and then turn yelloworange again in the fall, providing beautiful colour changes throughout the year.

‘Emperor 1’ Japanese maple leaves during spring colour.

Acer palmatum ‘Sango Kaku’.

Acer palmatum var. dissectum ‘Tamukeyama’.

Acer palmatum ‘Shishigashira’.

Acer palmatum ‘Crimson Queen’.

Photo by David J. Strang.

Photo by David J. Strang.

Photo by Famartin.

Photo by Johnathan Billinger.

Photo by David J. Strang.

Photo by David J. Strang.

Alternative small trees to Japanese maples that thrive in colder climates

Amur maple ( Acer ginnala) can grow 15 to 20 feet tall. This hardy maple is known for its small, finely textured leaves, which turn fiery red in fall. It’s adaptable to a range of conditions and is often used for hedging or as a specimen tree in colder climates. Hardy to zone 2.

Saskatoon ( Amelanchier) typically grows 15 to 25 feet

tall. This multi-stemmed tree or large shrub produces white flowers in early spring, followed by edible berries. The leaves turn stunning shades of orange and red in fall. Serviceberries are very hardy, tolerating zone 2, with certain varieties hardy in zone 1.

Korean maple ( Acer pseudosieboldianum) can reach heights of 15 to 25 feet. This maple resembles Japanese

Acer ginnala.

Acer griseum close-up.

Sorbus aucuparia.

Amelanchier alnifolia.

Photo by Arnstein Rønning.

Photo by Sten Porse.

maples in its leaf shape and brilliant fall colours of red, orange, and yellow. Unlike its Japanese counterparts, it is hardy in zone 4, and possibly zone 3.

Mountain ash (Sorbus aucuparia) grows 20 to 30 feet tall. It has delicate, pinnate leaves and produces clusters of white flowers in spring, followed by bright orange or red berries. In autumn, the foliage turns orange to purple. It’s quite hardy, thriving in zone 3.

Paperbark maple ( Acer griseum) can reach 20 to 30 feet tall. This tree is known for its exfoliating, coppercoloured bark, which adds year-round interest. The leaves turn from green to shades of red and orange in

fall. It’s a little less hardy, guaranteed around zone 4.

Ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius) grows 5 to 10 feet tall. It’s a versatile shrub with dark foliage (especially in varieties like ‘Diabolo’ or ‘Summer Wine’), making it a great alternative to Japanese maples for colder climates. In addition to its ornamental bark, which peels, it produces white flowers in spring. It is hardy to zone 2.

American hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana) reaches 20 to 30 feet in height. This tree is known for its smooth, muscular-looking bark and vibrant orange to red fall colours. It’s highly tolerant of a variety of soil conditions and cold hardy to zone 3. q

Acer pseudosieboldianum.

Physocarpus opulifolius ‘Diabolo’.

Carpinus caroliniana in autumn.

Photo by Kenrais.

Photo by David J Stang.

Photo By James Steakley.

Joe Pye weed

Story by Dorothy Dobbie

Ihad heard of and seen Joe Pye weed throughout my gardening life, but I did not learn to respect it until I saw it taking pride-of-place in a lovely English garden. It was tall and imposing, showing off its purple and dark green leaves and in full rosy bloom, buzzing with bees. I fell in love.

Joe Pye weed is the common name for Eutrochium, a member of the family Asteracea, and a classification to which Eupatorium has been assigned. Eupatorium is the name most commonly used in Canadian greenhouses.

This versatile plant has many qualities and therefore has a whole list of common names: boneset, kidney root, gravel root, snake root, and thoroughwort to name a few. In early days, various types were used medicinally to treat infectious diseases carried by ticks, lice, mites and rat fleas. Joe Pye weed treated

fever, headache, rashes, not to mention rheumatism, gout, breathing problems and diarrhea.

The name Joe Pye is attributed to a Mohican named Joseph Shauquethqueat (also Zhopai), known to the settlers in 17th-century New England as Joe Pye. He saved a community from death by typhus using E. purpureum, whose leaves, flowers and roots are all useful. It is said that the plant contains flavonoids and euparin, a mild antioxidant.

Today, we grow Joe Pye weed for its ornamental value and because it is very bee and other pollinator friendly. Goldfinches love to feast on the seeds produced at the end of the summer.

It is also a forgiving perennial in the garden, blooming about six weeks but, under the right conditions, up to 10 weeks. It likes exposure in sunlight to light shade and soil that is rich but well drained, but

it is not that fussy and will generally grow wherever you put it. However, that beautiful specimen I saw in England was clearly responding to some garden empathy. I would suggest giving it lots of water because in the wild, it thrives at the margins of sloughs and wet ditches.

Joe Pye is generally a large plant that can create a 4-foot-wide clump so if you have a small garden there are now dwarf varieties you can grow. You can also cut back stems to half in June and this will result in a shorter, bushier plant with more stems, topped with flowers, that grow in umbels reaching as much as 8 inches across.

Good plant companions include Karl Foerster grass, Echinacea (purple cone flower), Helenium, Monarda and Persicaria

Spotted Joe Pye weed (E. maculatum) when wet and

happy, can grow to 8 feet tall. This is the one with the fluffy flowers. It is one of the very long bloomers, putting out umbels that can, in some species, get as large as 8 inches across.

On the other hand, sweet-scented Joe Pye weed (E. purpureum) is often confused with spotted Joe Pye weed, but has regular blossoms and smells like vanilla.

Hollow Joe Pye weed (E. fistulosum) is the tallest of the Joe Pye weeds, reaching 10 feet tall and sending out whitish-pinkish flowers late summer to early fall. Leaf cutter bees will overwinter in its hollow stems.

And there is also coastal Joe Pye weed (E. dubium) which has been hybridized for the smaller statured ‘Baby Joe’ and ‘Little Joe’.

Clearly, Joe Pye weed is best loved by those who like pollinator gardens and large plants and who love to attract pollinators and birds. q

Eupatorium purpureum ‘Euphoria Ruby’.

Eupatorium dubium ‘Little Joe’.

Eupatorium maculatum ‘Atropurpureum’.

Eutrochium fistulosum.

Photo by Cbaile19.

Image courtesy of Darwin Perennials. Image courtesy of Ball Horticultural Inc. Image courtesy of Ball Horticultural Inc.

Easy ZZ

Story and photos by Dorothy Dobbie

Many a would-be indoor gardener has been lost to the brown thumb league because they can’t keep tropicals alive. This probably has more to do with busy lifestyles than lack of ability, so I have an answer.

What if you had a plant that could live up to four months without being watered (not that I recommend this)? You could travel worry free and still come home to a green welcome and no nagging sense of guilt.

The miraculous ZZ plant is your answer. Not only is it easy-care, but it is very green and will even bloom under the right conditions. Yes, it blooms!

Its full name is Zamioculcas zamiifoila and it hales from Eastern Africa – exotic places such as Kenya, Mozambique and Zimbabwe, to name a few of its hosts. It has a lot of more casual names, among them emerald palm, Zanzibar gem, aroid palm and eternity plant, my favourite.

The toughness of this little gem – it grows to about 2 feet tall at its finest – comes from its remarkable ability to retain moisture. Its plump, glossy leaves are about 91 percent water, its leaf stems about 95 percent. The plant grows from tough underground rhizomes that know how to seek out the best the soil has to offer.

Despite this, it is not immortal and will be happiest if you water it every two to four weeks – be sure to let it dry out between waterings. It also prefers a bright room with indirect sunlight, but it will be equally pleased in a windowless room, surviving quite happily in artificial light. And in this case, you can water even less.

Overwatering is the biggest problem indoor gardeners encounter with ZZ plants. If you are overwatering, you may see the leaves turn yellow and drop off. If this happens, dry the plant out and give it a bit more light for a couple of weeks. It will revive. Make sure the plant drains well, and don’t allow excess moisture to collect and create a well of standing water.

ZZ is a member of the Arum family and, like its cousin the peace lily, its flowers are stout spadix types emerging from the soil at the base of the stems. The tongue shaped spadix is encased in a sheltering spathe. These plants seldom bloom indoors so its failure to do so is not your fault as a gardener.

ZZ is a true tropical and doesn’t like to get chilled. The temperature should not fall below 15 Celsius but it also resents very high temperatures exceeding 26 Celsius.

Propagation is easy. Simply prune one or more of the stems near its base and then put the pruned branch into a glass of water.

Like any other house plant, ZZ enjoys a summer holiday outdoors when you can feed it with a 50 percent dose of the usual fertilizer. Transplanting is best done in spring before it begins its seasonal growth spurt but if it is too crowded you can pot it up in a bigger home anytime.

This plant can attract the usual family of insects: aphids, spider mites, scale or mealybugs, but if your home is insect fee, you should be fine.

Enjoy ZZ. You will be well rewarded for very little extra care. q

ZZ plant blossom.

Box elder bugs

Story by Shauna Dobbie

It may be alarming to see a mass of orange and black insects clustered together in the fall – even trying to gain access to your house – but don’t worry. Box elder bugs are harmless to people, animals and even plants.

Box elder bugs (Boisea trivittata in Canada from Manitoba to the Maritimes, B. rubrolineata in Saskatche-

wan, Alberta and BC) are a common insect species in North America, often associated with the Manitoba maple (also known as box elder), other maples and ash trees, which provide their primary food sources. These insects become most noticeable in the fall when they congregate on the sunny sides of buildings and other structures, seeking warmth as

temperatures drop.

In terms of appearance, box elder bugs are around ½ inch long. They have a black body with prominent red or orange markings, including three distinct stripes that run along their back. When at rest, their wings lie flat against their bodies, giving them a somewhat elongated, oval shape.

A mass of box elder bugs on a fencepost in Bolton, Ontario in September 2018.

Photo by Kelisi.

Western box elder bug.

Adult and nymphs near Stirling, Ontario.

Photo by Jesse Keith Huffman.

Photo by Judy Gallagher.

One particularly interesting aspect of box elder bugs is their ability to form large, conspicuous aggregations in the fall as they prepare to overwinter. These gatherings can involve thousands of individuals, all clustering together on sunny walls or trees, creating a striking visual display. What’s fascinating is that box elder bugs are believed to communicate with each other using chemical signals, or pheromones, which help them locate these communal gathering spots.

This behavior isn’t just about warmth, it also plays a role in their survival. By clustering together in large groups, they can create a microenvironment that helps retain heat, reducing the risk of freezing during cold months. Additionally, this group behavior can serve as a defense mechanism, making it harder for predators like birds or spiders to pick off individual bugs from a large swarm.

The life cycle of a box elder bug consists of three stages: egg, nymph, and adult. In the spring, females lay their eggs on the leaves, bark, or seeds of their host trees. These eggs are initially yellow but turn reddish as they develop. After hatching, the nymphs are small, wingless, and bright red. As they mature, they gradually acquire their black markings and wings. Adults live for several months, and in warmer climates, they may produce one or two generations each year.

Box elder bugs typically live near

Classifieds

BOB’S SUPERSTRONG GREENHOUSE POLY.

10 & 14 Mils. Pond liners. Resists hail, snows, winds, yellowing, cats, punctures. Long-lasting. Custom sizes. Free samples. Email: info@northerngreenhouse.com www.northerngreenhouse.com Ph: 204-327-5540 Fax: 204-327-5527 Box 1450 Altona, MB R0G 0B0

To place a classified ad in Canada’s Local Gardener, call 1-888-680-2008 or email info@localgardener.net for rates and information.

Lookalike insect

Melacoryphus lateralis looks a lot like the box elder bug, and they have many of the same habits. These are more prevalent in desert areas of the US but are present in BC, Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Just as harmless as box elder bugs, don’t get upset if you see them. If you’re really determined to know which red and black bug you’re looking at, this one has red stripes only on the outside of its wings.

their host trees. However, in the fall, they are known to seek warmth and shelter, which often brings them into homes and buildings. Inside, they can be found in cracks, crevices, and other protected areas where they overwinter. While box elder bugs do not bite or sting, nor do they cause

structural damage, they can be a nuisance when they gather in large numbers indoors. When crushed, they emit an unpleasant odor, and their excrement can leave reddish stains on surfaces.

These insects feed primarily on the seeds, leaves, and stems of Manitoba maple trees and other maples and ash. They pierce plant tissues to extract sap, but they rarely cause significant damage to the trees they feed on.

Although they are not harmful, controlling box elder bugs can become necessary, especially when they invade homes. Preventative measures include sealing cracks, gaps, and openings around windows, doors, and other entry points to prevent them from entering. If they do get inside, vacuuming or sweeping them up is the most effective way to remove them without causing stains or smells.

Box elder bugs are most active in late summer and fall. During the spring and summer, they feed on their host plants outside. As the weather cools in the fall, they begin looking for warm places to overwinter, which is when they are most likely to be noticed in homes or other structures. If you are truly offended by the sight of them, you should know that they have a strong attraction to the same overwintering sites year after year, which can lead to colonies persisting in the same location for generations. Our best advice? Get over your disdain and use a broom to dispatch them from your home. q

Join the conversation with Canada’s Local Gardener online! www.localgardener.net Facebook: @CanadaLocalGardener Instagram: @local_gardener X: @CanadaGardener

Lookalike insect Melacoryphus lateralis.

Photo by Junkyard Sparkle.

How to build an arbour

Building an arbour is a relatively straightforward project that can enhance the beauty of a garden or walkway. Here's a stepby-step guide on how to build a basic garden arbour:

Materials

• 4 wooden posts (4x4 or 6x6) for the vertical supports

• 2 cross beams (2x6 or 2x8) for the top

• 2 to 6 rafters (2x4 or 2x6), depending on the size of your arbour

• Wood screws or nails

• Concrete (if setting the posts in the ground)

• Measuring tape

• Level

• Drill or hammer

• Saw

• Pencil and string

Step-by-step instructions:

1. Choose a location. Decide where you want to place the arbour. Typically, they are positioned over a pathway, entrance, or in a garden as a decorative feature.

2. Plan the dimensions. Determine the size of your arbour. Standard arbours are about 7 to 8 feet tall and 4 to 6 feet wide, but you can adjust this based on your needs. Mark the placement of the posts.

3. Set the posts

• Dig holes: If you're setting your arbour into the ground, dig four holes for the posts. They should be about 3 to 4 feet deep for stability, depending on your soil type.

• Add concrete: Place the posts in the holes and pour concrete around them. Use a level to ensure the posts are vertical and allow the concrete to cure for at least 24 hours.

4. Attach the cross beams

• Once the posts are set and stable, attach the cross beams across the top. These are the horizontal pieces that will form the top frame of your arbour.

• Screw or nail the cross beams into the posts, making sure they are level.

5. Install the rafters

• Cut and attach rafters across the cross beams, spacing them evenly.

Story by Shauna Dobbie

These will give the arbour its traditional look, with the beams providing shade or support for climbing plants.

• You can add decorative cuts to the ends of the rafters (such as a curve or diagonal cut) to give the arbour a more polished look.

• Secure the rafters to the cross beams using wood screws or nails.

6. Add decorative elements (optional). If desired, install lattice or horizontal slats on the sides for additional support for climbing plants.

7. Finishing touches

• Sand any rough edges and apply

a sealant, stain, or paint to protect the wood from the elements.

• If your arbour will support heavy plants, consider additional bracing for extra stability.

Tips:

• Wood choice. Use pressure-treated wood, cedar, or redwood for durability, especially if the arbour will be exposed to the elements.

• Anchoring. Ensure your arbour is well-anchored if you live in a windy area.

• Climbing plants. Consider planting vines to grow over the arbour for a lush, green canopy.

Depending on your tastes, you can make your arbour as simple or as funky as you want.

Photo by Gail Aslanian.

Vines for your arbour

Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) is a fastgrowing deciduous vine that thrives in zones 2 to 9. It produces lush green foliage that turns a brilliant red in the fall, making it a beautiful addition to an arbour. It will become rampant in your garden and can grow to a height of 30 to 50 feet, providing excellent coverage. Look for the variation called Engelmann’s ivy; it’s less vigorous and doesn’t have adhesive pads that allow it to climb, so you’ll have to attach it to your arbour.

Climbing honeysuckle (Lonicera dioica) is a great choice for zones 2 to 7. This vine produces clusters of red and yellow flowers, which attract hummingbirds and other pollinators. It grows to about 10 to 15 feet, making it a perfect size for smaller arbours. It is native across Canada.

American bittersweet (Celastrus scandens), hardy in zones 2 to 8, is another option for adding seasonal interest. This vigorous vine produces yellow-orange berries in the fall, which are often used in ornamental arrangements. Reaching a height of 15 to 20 feet, it needs both male and female plants to produce its vibrant fruit.

Dutchman’s pipe ( Aristolochia macrophylla) thrives in zones 4 to 8 and is known for its large, heart-shaped leaves and unique pipe-shaped flowers. This vine grows to about 20 to 30 feet and is great for providing dense shade, making it ideal for covering arbours or pergolas.

Clematis ‘Jackmanii’ (Clematis x jackmanii) is a popular clematis variety for zones 3 to 8, known for its large, deep purple flowers that bloom from midsummer to early fall. This vine typically grows to about 10 to 15 feet and adds a touch of elegance to any arbour with its showy blossoms. Any vining clematis that grows well in your area would be ideal.

Boston ivy (Parthenocissus tricuspidata), which grows well in zones 4 to 8, is another self-clinging climber with glossy leaves that turn a fiery red in the fall. This vine grows rapidly, reaching heights of 30 to 50 feet, and is excellent for creating lush, green walls on arbours.

Trumpet vine (Campsis radicans) is a vigorous, fastgrowing vine suitable for zones 4 to 9. Its tubular orange-red flowers are a magnet for hummingbirds and provide a splash of colour throughout the summer. This

vine can grow between 20 to 40 feet, but it requires regular pruning to keep it in check.

Arctic kiwi ( Actinida arguta) is a great option for zones 2 and up. This fast-growing vine has small white flowers which, if you provide a male and a female, will become grape-sized kiwis. It can quickly reach heights of 20 to 40 feet, providing excellent coverage for arbours. Fruit can take some years to develop.

Virgin’s bower clematis (Clematis virginiana) is a charming vine that thrives in zone 3 and up. It produces fragrant white flowers through summer, making it an excellent choice for adding mid-season interest to your arbour. This vine can grow up to 20 feet. It is native from Nova Scotia to Manitoba.

Western white clematis (Clematis lingusticifolia) is similar to virgin’s bower but with bigger flowers. Native to BC and Alberta, it reaches heights of 12 to 30 feet. Hardy to zone 3.

Prairie traveler’s joy (Clematis occidentalis) has little nodding bell shaped flowers in purple, hardy to zone 2. Grows 6 to 10 feet high, so plant one on either side of an arbour. Native from BC through Ontario, it is hardy to zone 2. q

Virginia creeper.

American bittersweet.

Clematis ‘Jackmanii’.

Photo courtesy of the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Climbing honeysuckle vine.

How to pave with stone

Story by Shauna Dobbie

Putting in a walkway or patio seems exhausting. If you’re a weakling like me, just carrying the pavers is tiring. Add to that shoveling gravel and sand and using a heavy tamper on it all?

But I want paths in my gardens, and I want them done right. The key for me is to work just a couple of hours at a time, because when I spend long hours at a physical task I get tired, and then I cut corners. This process requires patience and atten-

tion to detail.

Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to lay stone for a patio or walkway. Materials and tools needed

• Stones (natural flagstone, pavers, etc.)

• Gravel (for the base)

• Sand or stone dust (for leveling)

• Landscape fabric (optional, for weed control)

• Shovel

• Rake

• Tamper or compactor

• Level

• Mallet (rubber)

• Garden hose or spray bottle (for moisture control)

• Joint filler (sand, stone dust, or polymeric sand)

• String and stakes (for marking the area)

• Safety gloves and knee pads (for comfort and protection)

1. Plan and design the area

• Measure and mark. Determine the area where you'll lay the stone.

Photo courtesy of iStock.com,

photo by Irina Zharkova.

Mark it using stakes and string. Measure the area to calculate how much stone, gravel, and sand you’ll need.

• Design. Plan the pattern or layout for the stones. Some people prefer an irregular, natural look with flagstone, while others prefer a more uniform, patterned look with pavers.

2. Excavate the area

• Dig the base. Dig out the area to a depth of around 4 to 6 inches for walkways and up to 10 inches for patios, depending on the thickness of the stones and the climate (deeper if you experience freezing winters).

• Remove vegetation. Make sure the area is clear of any roots, grass, or weeds.

• Optional. Install landscape fabric over the excavated area to help prevent weeds from growing between the stones. Pay for the heavy-duty stuff!

3. Create the base

• Add gravel. Pour a 2-to-4-inch layer of gravel into the excavated area. Use a rake to spread it evenly.

• Compact the base. Use a tamper or plate compactor to firmly compact the gravel. This ensures a stable foundation. A tamper is cheap, but a plate compactor (rent it) is easier.

4. Add sand, stone dust or screenings

• Spread sand, stone dust or screenings. After compacting the gravel, spread a 1-to-2-inch layer of

sand or stone dust over the area.

• Level the surface. Use a long piece of wood or a screed board to smooth out and level.

5. Lay the stones

• Set the stones. Begin placing your stones on the sand or stone dust, starting from a corner or edge. Fit the stones together like a puzzle, leaving small gaps for joint filler if desired.

• Check level. Use a level to ensure each stone is level with the adjacent stones. Tap down stones with a rubber mallet to make adjustments.

• Cut stones (if needed). For more uniform patterns or tight areas, you may need to cut stones to fit. Use a chisel and hammer or a wet saw for more precision. (I think I’ll just build pathways that don’t require cutting pavers.)

6. Fill the joints

• Fill the gaps. Once all the stones are in place, fill the gaps between the stones with joint filler (sand, stone dust, or polymeric sand).

• Spread filler. Sweep the filler material over the surface and into the gaps between the stones.

• Compact again. Use a tamper to lightly compact the stones again, which will settle the filler into the joints.

7. Mist and set the filler

• If using polymeric sand, mist the surface lightly with water to activate the binding agents. Avoid overwatering as this can cause the sand to wash out of the joints.

• Check for settling. After a day or two, check if any joints need more filler and add as necessary.

8. Clean the surface

• Sweep off any excess filler material from the surface of the stones to prevent it from hardening on the stone.

• Hose down the stones lightly to settle any remaining dust or debris.

I will have to order gravel and screenings to be delivered because it’s much cheaper than buying bags of it at the big box store. And I’ll have to order pavers as well; I don’t see myself futzing about with getting flagstones all level.

I’ll have to buy a tamper because the project will take far too long to rent a plate compactor, although there is one from Vevor for around $600.

And I’ll need landscape fabric.

I think I can do this! Easy-peasy lemon squeezey, right? q

Excavate the area for the paving stones.

photos.

photos.

in the base material.

Level the surface and frame the area.

Garden reno on the cheap

Story by Shauna Dobbie

With the garden put to bed for the season, whether you clip everything down or leave the stalks for the bugs and birds, it’s time to think about next year. What are you going to do to make your 2025 garden the best that it can be? And how can you do it without spending a fortune?

Use your creativity, resourcefulness, and a little effort. Some of the best gardens aren’t the ones full of expensive planters and pathways; they are the ones full of love and expression.

1. Repurpose items you already have

• Old containers as planters. Use unused household items like buckets, cans, or old pots to create unique planters. You can paint them to give them a new look.

• Wood pallets or old furniture. If you have an old piece of furniture or wood pallets lying around, turn them into raised garden beds, plant stands, or vertical gardens.

• Mirrors and picture frames. A mirror can double the visual space. Just be careful to place it where birds are unlikely to fly into it. Put a potted plant into a picture frame and enjoy the beauty.

2. Rearrange your plants

• Relocate and divide plants. Most perennials can be divided, allowing you to create new plant groupings in different parts of the garden. This can change the look of your garden without purchasing new plants. Also? Many perennials benefit from dividing. One sign that it’s time is the plant getting bare in the centre.

• Swap plants. Trade cuttings or divisions with neigh-

bors or friends to introduce new species to your garden.

3. Create garden pathways

• Use materials on hand. When my husband and I bought our first house in Toronto, we put in a back patio with broken concrete from around the yard. No base or anything, we just dug out space in the mud. And we kept it for 20 years!

• Use mulch or gravel. Have these delivered to cut down the cost. You can put in plastic edging to make the pathway last longer or you can just freestyle the paths for a shorter period.

4. Compost for free fertilizer

• Start a compost pile. If you aren’t already making compost, do it. Composting kitchen scraps and yard waste can create nutrient-rich soil enhancement for your plants. It’s a free way to improve plant health. It’s easier than you might think!

5. Use found objects for art and structure

• DIY garden art. Collect rocks, branches, or other natural items from your surroundings to create artistic features like stone towers, twig trellises. Paint on them for rustic plant labels!

• Create a trellis or plant support. Use long sticks, branches, or old wire to create simple trellises for climbing plants.

6. Mulch with free organic materials

• Use leaves and grass clippings. Collect fallen leaves or grass clippings to use as mulch around your plants. This helps conserve moisture and adds nutrients

Gather up the fall leaves and use them as mulch for the garden.

to the soil as it breaks down.

• Cardboard for weed control. Lay down sheets of cardboard in garden beds to suppress weeds and cover them with organic materials like leaves or wood chips.

7. Grow from seeds or cuttings

• Start from seed. Instead of buying plants, grow flowers, vegetables, or herbs from seeds you already have or can gather from friends or other plants.

• Propagate from cuttings. Many plants can be propagated from cuttings, so take cuttings of herbs, shrubs, or perennials and start new plants for free.

8. Use free and low-cost community resources

• Join plant exchanges. Some communities organize plant swaps or offer free plant divisions. Look for local gardening groups or online platforms like Facebook Marketplace to find free plants.

• Join a garden club or horticulture group. If you don’t have gardening friends, this is a good place to get some. Look online to find one near you. Membership fees are truly affordable.

10. Enhance your garden’s structure

• Create borders with natural materials. Use stones, logs, or old bricks to define garden beds or pathways. This can give the garden a more organized and defined appearance.

• Prune and shape. Simply pruning your existing plants into new shapes can give your garden a tidier and more maintained appearance. q

A great yard or garden begins with a great foundation. Reimer Soils has been providing the highest quality landscaping products for more than 40 years. With a complete range of top quality products and unmatched customer service, there is no reason to look any further than Reimer Soils for all your landscaping supply needs.

Turn yard and kitchen waste into valuable compost for the garden.

Photo by Eileen Mak.

Alternative lawns

Story by Holly Burke

The neatly manicured, lush, green lawn has been a symbol of suburban perfection across Canada. Maintaining a traditional grass lawn even under the most arduous conditions has been a point of pride for many homeowners for generations. However, as environmental awareness grows and the realities of climate change become increasingly apparent, the desire for sustainable alternatives to traditional lawns is growing. Moreover, not everyone enjoys the weekly mowing, and frequent watering necessary to maintain a green grass masterpiece, and why should they have to?

There are plenty of environmentally conscientious, aesthetically pleasing, low-maintenance alternatives. It might be time for Canadians to creatively rethink their outdoor spaces with an escape from maintenance woes and greater eco-consciousness in mind.

Why might alternatives be more environmentally friendly?

1. Gas mowers contribute to air pollution. According to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates, gasoline-powered lawn and garden equipment (GLGE) were responsible for 6.3 million tons of VOCs, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, particulate matter (mostly fine particulate matter which has many health consequences), plus 20.4 million tons of carbon dioxide in 2011. Low or no-mow lawn alternatives cut back on these emissions. Even reducing the amount of typi-

cal grass in a garden would cut back on mow time and, therefore emissions.

2. Herbicides and pesticides can have serious health consequences for humans. These chemicals also end up in our water supply via groundwater and runoff. Many lawn alternatives naturally suppress weed growth, which could reduce or eliminate the need for toxic weed killers. Some options could also reduce or eliminate the need for pesticides.

3. Chemical fertilizers often required for our lawns can pollute air, water, and soil. Most of the alternatives growing in popularity do not require fertilizing.

4. Lawns require a lot of added water, which increases our water bills and demands a lot from our urban water infrastructure. As climate change is causing more droughts, our traditional lawns use more water than we might like. Many lawn alternatives do not require nearly as much water.

So, what exactly are some of these alternatives, and what might a yard look like with a little imagination and investment?

Meadow lawns (aka tapestry lawns) that include native plants increase biodiversity, heal the soil, and are good for our air. This stunning option only needs to be cut down once a year before winter. Native plants are quite resilient to the conditions of the area they belong in. Finding out which native varieties to plant and how

Many have replaced their lawn with a wildflower meadow!

to properly establish a meadow may seem difficult, but once established this pollinator-friendly option can take care of itself easier than you might think.

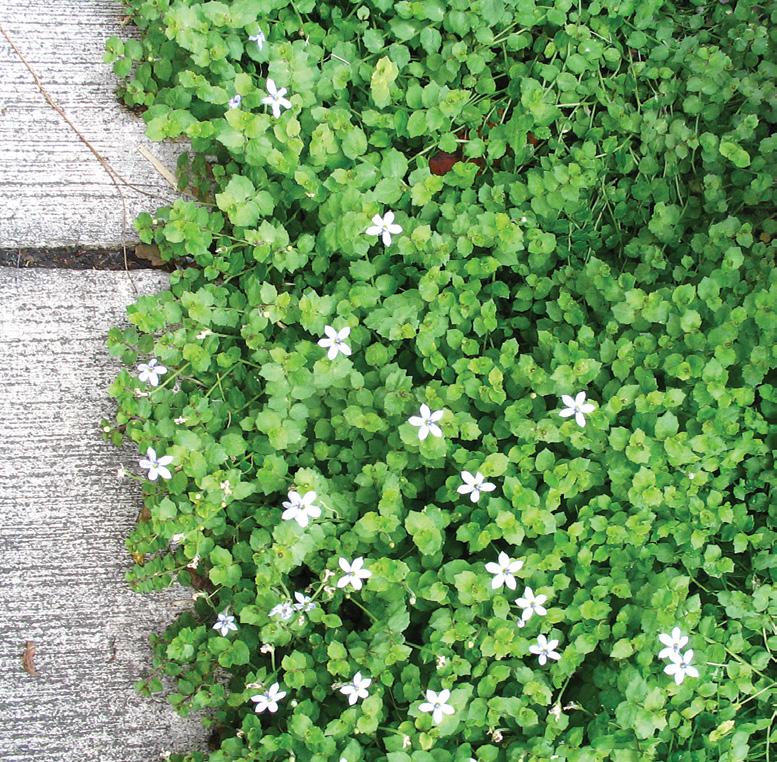

Herbal groundcovers can add lovely colour, texture, and scent. Creeping thyme is quite resilient. It adds a sense of peace and a pretty pop of purple to your space. However, it is only lightly trample-resistant, like most groundcovers. You can place thyme throughout rock gardens, or on the outskirts of higher-traffic areas of more trample-resistant options, like clover or hard fescue.

Herbal options may be best for lower-traffic areas. These herbal covers can be mowed when necessary, but require little maintenance. Winterizing one of these lawns for harsh winters may be challenging, however, as you need to cover it in a layer of loose mulch such as leaf mould. These herbs are so beautiful they may be worth some trial and error. Bonus of herbal options: many herbs deter pests and mosquitos!

Moss is a ground covering that can thrive in the right spaces. Many varieties like shade, but some might be happy enough in some sunlight. Some moss varieties are hardy enough to walk on. It can be added along rock or mulch gardens or have paths paved through it.

Hard fescue, Dutch white clover, and microclover, or a mix of clover and low- or no-mow grasses, are functional grass alternatives that can thrive in Canada. While some of the previously mentioned options may be appealing to some folks and some could be truly stunning, people with children and pets might need something more like a typical lawn regarding walkability.

Hard fescue and some other fescue grasses don’t need much mowing and are resilient to drought and freezing. Fescue can also be mixed with clover. It is trampleresilient enough for children and pets to enjoy.

Clover is gaining popularity for many reasons. It requires much less frequent mowing than a typical lawn, requires less water, can handle children and pets running around, and does not require fertilizer. Dutch white clover produces white flowers that attract pollinators, which increases biodiversity (hello butterflies!), but those with bee allergies or children playing in yards may wish to avoid them. Microclover flowers too, but much less. Mowing more often can keep flowering at bay if you don’t like it.

Rock gardens, which can help to prevent soil erosion, are a lower maintenance option that can suppress weeds and allow water to flow freely. An entire yard could be a rock garden, with plants, flowers, or herbs throughout. Alternatively, they could service just a portion of a yard also occupied by some of the options listed above or provide a path through a meadow lawn.

Bylaws

It should be noted that some cities may have restrictions on certain alternatives due to the threat they may pose of spreading to neighbouring lawns, but this doesn’t need to limit you. Talk to your neighbours and look into your city’s bylaws. With so many interesting options to choose from, there would certainly be a way to satisfy your desires without upsetting the neighbours or the city. Neighbourhoods could be filled with creative, beautiful, eco-conscious lawns! q

Creeping thyme.

White clover.

Methods for putting in a new bed

Story by Dorothy Dobbie

It might surprise you to know that planning a new garden doesn’t start with digging out some sod. It begins with scouting out the best location and that will depend on what you want to grow.

If it is vegetables or sun loving flowers, you will need a spot that gets at least six to eight hours of sunlight a day for most of these plants. Anything else is considered shade, from light to heavy. Light sunlight may be space near the outer edge of the canopy of a large tree where dappled shade can sift through the leaves. It may also be a place that is sunny for less than six hours. Heavy shade might be a location close to the north side of a house that seldom gets any sunlight. If the location you are favoring is near a tree, consider how large that tree will become. It can ultimately steal your sunshine, and its roots can steal moisture and interfere with plant

growth.

Secondly consider wind. If you are planting tall plants such as corn or delphiniums, wind can be a big factor. Finally, what is the drainage like? Does water collect in that spot you’ve chosen? Does it drain quickly?

Now that you have scoped out the location, you can begin the physical work. There are several possibilities.

Digging

If you live where the soil is sandy, digging is a realistic option. If you are planning to start planting the same year, you won’t have time to deal with the sod breaking down. Slice the sod in strips then pull it back before you begin. You can pile the removed sod, grass side down, in your compost pile.

In the old days, you would be encouraged to dig, rake, and break down the exposed soil to make it nice

It pays to do your research to figure out the growing conditions in your yard to help you decide which plants to choose from.

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock, photo by

P-Jitti.

Get to know your soil – it is the foundation for your garden. and smooth. Today, disturbing the soil more than necessary is considered undesirable. Digging wet or very dry soil is not recommended either. Digging in wet soil can damage the structure. Digging dry soil can be very difficult to do when the ground is hard and dry. Early spring, after the snow has disappeared and the soil is just damp enough to form a loose ball is the best time. We call this soil “friable”. You can dig easily without too much disturbance of the under surface eco system.