IN RESEARCH FALL 2022 allen Online Privacy Anti-Racism rothman Navigating the Identity Thicket yoo Contemporary First Amendment Protections

ADVANCES

The faculty at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School dedicate themselves to producing research and scholarship that illuminates the most pressing issues facing society today. From net neutrality, artificial intelligence, and climate change to cutting-edge research on corporate governance, privacy law, and achieving racial, social, and economic justice, and more, our professors discover and share pathbreaking insights that push the legal academy forward and reshape real-world policy.

Our faculty members are interdisciplinary thinkers who bridge the gap between the law and myriad connected fields by collaborating extensively with scholars from institutions around the country and throughout the world. Their work exemplifies diverse methodologies and perspectives, revealing the wide range of modes of thought and areas of academic inquiry that thrive here at the Law School.

In this issue of Advances in Research, we offer a snapshot of some of the most noteworthy research and scholarship conducted by our faculty over the past year. The featured faculty members include both longstanding experts in their fields and promising scholars at the beginning of their careers. We hope you enjoy this edition.

Ted Ruger Dean and Bernard G. Segal Professor of Law

Sincerely,

RESEARCH BY 2 ALLEN Online Privacy Anti-Racism 4 BURBANK Class Certification in the U.S. Courts of Appeals 6 COGLIANESE Algorithm vs. Algorithm 10 FISCH ESG Promises 12 GALBRAITH Runaway Presidential Power Over Diplomacy 14 HARRIS Taking Disability Public 16 HOFFMAN (A.) The Future of America’s Health Insurance 18 HOFFMAN (D.) Longer Trips to Court Cause Evictions 20 HOVENKAMP The Invention of Antitrust 22 KOSURI Nowhere to Run to, Nowhere to Hide 24 MAYERI Equal Protection and Abortion 26 MAYSON Pretrial Detention and the Value of Liberty 28 OSSEI-OWUSU Velvet Rope Discrimination 30 PARCHOMOVSKY Third Party Moral Hazard 32 POLLMAN The Corporate Governance Machine 34 ROTHMAN Navigating the Identity Thicket 36 TANI Lost Disability History of the ‘New Federalism’ 38 WANG Pandemic Governance 40 WELTON Neutralizing the Atmosphere 42 YOO Contemporary First Amendment Protections

ONLINE PRIVACY ANTI-RACISM

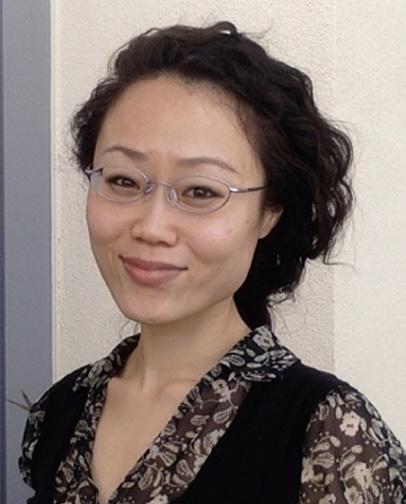

ANITA L. ALLEN Henry R. Silverman Professor of Law and Professor of Philosophy

In “Dismantling the ‘Black Opticon’: Privacy, Race Equity, and Online Data-Protection Reform,” published in the Yale Law Journal Forum, Allen introduces a critical analysis of the particularized vulnerabilities African Americans experience through online surveillance, exclusion, and exploitation. Allen terms this intersecting pattern “the Black Opticon.”

In her African American Online Equity Agenda (AAOEA), Allen set sets forth a “specific set of policymaking imperatives . . . to inform legal and institutional initiatives toward ending African Americans’ heightened vulnerability to a discriminatory digital society violative of privacy, social equality, and civil rights” and uses this framework to analyze three potential legislative solutions. Ultimately, her work delineates the urgent need for explicitly antiracist data protection policies that better serve African Americans.

African Americans Disparate Online Vulnerability

African Americans face disparate online vulnerability in three distinct categories: discriminatory oversurveillance, discriminatory exclusion, and discriminatory predation.

Allen examines how location-analytics software exposes African Americans to disproportionate risks of privacy invasion. In 2016, several major online platforms faced harsh criticism for providing user data to Geofeedia, a software company that used social media posts and facial-recognition technology to analyze and collect a history of individuals’ locations, which it then marketed to law enforcement. After African American Freddie Gray was killed while in police custody, police in the majority-Black community of Sandtown-Winchester used data purchased from Geofeedia to find and arrest individuals who participated in ensuing Black Lives Matter protests.

“Location tracking, the related use of facial-recognition tools, and targeted surveillance of groups and protestors exercising their fundamental rights and freedoms are paramount data-privacy practices disproportionally impacting African Americans,” Allen writes.

Discriminatory exclusion involves “targeting Black people for exclusion from beneficial opportunities on the basis of race” by collecting information that, when analyzed, identifies a person as African American.

When Dr. LaTanya Sweeney, an African American Harvard professor and former Chief Technology Officer at the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), searched “LaTanya Sweeney,” Google returned an advertisement for InstaCheckmate.com that read “LaTanya Sweeney Arrested?” Sweeney contrasted this with her search for the more ethnically ambiguous “Tanya Smith,” which did not return the same arrest advertisement. From this, Allen writes that “biased machine learning can lead search engines to presume that names that ‘sound Black’ belong to those whom others should suspect and pay to investigate.”

on research by

on research by

2

ANITA L. ALLEN

“Existing civil-rights laws and doctrines are not yet applied on a consistent basis to combat the serious discrimination and inequality compounded by the digital economy.”

In addition to identifying users as African American, online platforms have leveraged this information to systematically exclude African Americans from viewing certain advertisements. These discriminatory practices prevent African Americans from participating in vital sectors of the market, including but certainly not limited to education, employment, housing, and loan procurement.

On the other side of discriminatory exclusion is discriminatory predation, or the targeted advertisement to African Americans of products meant to “induce purchases and contracts through con jobs, scams, lies, and trickery.”

“Discriminatory predation makes consumer goods such as automobiles and for-profit education available, but at excessively high costs,” Allen writes. “Predation includes selling and marketing products that do not work, extending payday loans with exploitative terms, selling products such as magazines that are never delivered, and presenting illusory money-making schemes to populations desperate for ways to earn a better living.”

An African American Online Equity Agenda

Allen employs her AAOEA to evaluate whether a new state law in Virginia, new privacy protection resources of the (FTC), or a proposed new federal privacy agency would adequately serve the online privacy interests of African Americans.

Though some activists have been successful in calling for industry-led self-governance, data privacy is embodied within several legal regimes, including data-privacy, antitrust, intellectual property, constitutional, civil rights, and human rights.

“At this critical time of exploding technology and racial conflict,” Allen writes, “I believe that policy making should be explicitly antiracist.”

The AAOEA centers on five points of guidance for anti-racist law and policy making, which Allen unpacks in turn:

• Racial inequality nonexacerbation

• Racial impact neutrality

• Race-based discriminatory oversurveillance elimination

• Race-based discriminatory exclusion reduction

• Race-based discriminatory fraud, deceit, and exploitation reduction

Assessing Enacted State Law: Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (2021)

While the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (2021) (VCDP) includes antidiscrimination provisions, it fails to “explicitly reference the interests of African Americans or antiracism as a legislative goal” and relies on insecure enforcement mechanisms.

Significantly, the law excludes massive sectors that crucially affect the day-to-day lives of African Americans. As Allen writes, “[t]he rationale for exempting all nonprofits regardless of size — as well as commonwealth governmental entities, including the police, jails, and prisons — is unclear,” though likely relates to the desire to make the unanimously-passed legislation “uncontentious.” Additionally, the law does not protect photographs and related data from being used by Virginia law enforcement, which is of particular concern to African Americans, who tend to be disproportionately impacted by the criminal justice system.

Moreover, though the law prohibits collecting personal data in violation of antidiscrimination laws, it is unclear that these measures will have a pragmatic effect in protecting African Americans’ data. Notedly, the VCDP permits targeted advertising so long as consumers have the right to “opt out.” Allen argues that placing the onus of “opting out” on the consumer is problematic, as it relies on the assumption that consumers are aware they may be being targeted based on their data — and possibly their race. Lastly, any enforcement of the VCDP falls at the discretion of the State Attorney General, with no right of private action, thus effectively subjecting the law to political bias and fluctuation.

New Resources for the Federal Trade Commission

Three factors may signal advancement in the FTC’s historically sparse track record of pursing enforcement actions related to online discrimination: continued diverse leadership, funding for a privacy bureau, and an express commitment to addressing problems faced by communities of color.

In 2021, President Joe Biden appointed Alvaro Bedoya, an immigrant from Peru and naturalized U.S. citizen, to serve as the Commissioner of the FTC. Thus far, Bedoya “has demonstrated an understanding of the problem of racial-minority-targeting surveillance.” Further, the U.S. House Committee on Energy and Commerce recently voted to create and operate a bureau within the FTC dedicated to fighting unfair practices and enforcing Congressional laws related to privacy, data security, and related matters. This proposal could potentially bolster existing race conscious antidiscrimination practices.

A Proposed Federal Data-Protection Agency

The Data Protection Act (DPA) of 2021 introduced by Senators Kirsten Gillibrand and Sherrod Smith in June of 2021 is “striking for its deep responsiveness to calls for equitable platform privacy governance.”

Among its components, the bill would create an autonomous Federal Data Protection Agency (FDPA) that would engage in policymaking, research, law enforcement, and protection against discrimination. The FDPA would include a Civil Rights Office to “regulate high-risk data practices and the collection, processing, and sharing of personal data,” which Allen notes fits squarely into the aims of the AAOEA.

Though the DPA is “not likely to move through Congress soon or intact,” the bill sets a “high bar for future legislative-reform proposals” and “signals a new era, laying out a dynamic framework for an agency with unprecedented authority to pursue equity in the context of data protection.”

In conclusion, according to Allen, without updated governance to reflect recent decades’ profound advances in technology, online platforms can reproduce racist social structures through their design –thereby amplifying discrimination, hate, and white supremacy.

“[T]he Black Opticon is a useful, novel rubric for characterizing the several ways African Americans and their data are subject to pernicious forms of discriminatory attention by racializing technology online,” Allen writes. “These reform agendas have a grave purpose, as grave as the purposes that motivated the twentieth-century civilrights movements.”

3

STEPHEN B. BURBANK David Berger Professor for the Administration of Justice, Emeritus

CLASS CERTIFICATION in the U.S. COURTS OF APPEALS

“Mindful that there were few Supreme Court class certification decisions in our earlier studies, and that they may not provide an accurate picture of class action jurisprudence (let alone class action activity) over time, we launched a project to fill a larger part of the empirical vacuum.”

In their new paper, “Class Certification in the U.S. Courts of Appeals: A Longitudinal Study,” published in Law & Contemporary Problems, Burbank and Sean Farhang of the University of California, Berkeley, continue their prior work tracing the counterrevolution against private enforcement of federal law, led first by the Reagan administration and then by conservative activists, business groups, and the Republican party.

In this groundbreaking study, the authors fill more of the empirical vacuum regarding class actions in the federal courts by analyzing and testing both prior empirical scholarship and commonly asserted claims, finding significant variation over time in appeal outcomes and greater ideological polarity among judges.

“Mindful that there were few Supreme Court class certification decisions in our earlier studies, and that they may not provide an accurate picture of class action jurisprudence (let alone class action activity) over time, we launched a project to fill a larger part of the empirical vacuum,” they write.

The Existing Literature: Data and Claims

The authors begin with a literature review that identifies the scholarship and common assumptions surrounding Rule 23(f), the Class Action Fairness Act of 2005 (CAFA), and final-judgment appeals involving Rule 23(b)(3). They note that most systematically collected data have focused on Rule 23(f), which went into effect in 1998, with much speculation on its influence.

“Many predicted at the time it was being debated, and asserted after it was promulgated . . . that it would (or did) disproportionately benefit defendants,” they write of the challenges to the rule’s facially neutral classification. “Although the published studies of experience under Rule 23(f) vary in many respects, until recently they appeared largely to confirm such predictions and assertions.”

Regarding CAFA, they discuss a study conducted shortly after its enactment by the Federal Judicial Center that found “a dramatic increase in the number of diversity class actions filed as original proceedings in the federal courts in the post-CAFA period.” The authors write that “perhaps assuming that this documented increase would translate into a similar increase in the courts of appeals, a number of scholars have claimed that the volume of class certification appeals increased after CAFA.” However, they do not find any empirical data to support this.

To conclude their literature review, they note that most existing studies “ignore final-judgment appeals, perhaps regarding them as trivial in number.” Yet, as final-judgment appeals constitute roughly half of all appeals between 2002 and 2017, they write that “their absence from existing studies significantly limits the inferences that can be drawn from them.”

4

on research by

Longitudinal Patterns in Certification Decisions

The authors created a comprehensive data set of 1,344 published and unpublished class certification decisions in the United States Courts of Appeals. The published decisions include all published panel decisions addressing whether a class should be certified from 1966 (when the modern Rule 23 became effective) through 2017. The unpublished panel decisions are collected from 2002 through 2017.

They find that both published and unpublished decisions grew sharply following Rule23(f), with interlocutory appeals constituting “14% of published decisions prior to 2000 and 57% of them from 2000–2017” and about 30% of non-published decisions from 2002–2017. Yet, while interlocutory appeals account for the greatest amount of growth, final-judgment interlocutory appeals were roughly balanced during the 2002–2017 period.

The authors find a similar spike in the number of decisions in cases seeking certification of state claims only after CAFA was passed in 2005. Since they could not reliably code claims in federal court under CAFA, they instead review cases seeking certification of state claims only. They discover that prior to CAFA’s passage in 2005, the majority of published decisions on certification were in cases seeking certification of federal claims only, while cases seeking certification of state claims only grew threefold following 2005. Additionally, “in published and unpublished decisions in 2002–2017, certification decisions on state law-only classes grew more strongly, increasing fivefold and becoming as frequent as certification decisions on classes asserting only federal claims,” they write.

The authors then examine “whether the growth in availability of interlocutory review had a disproportionate impact on the proportion of appeals addressing (b)(2) versus (b)(3) classes.” It has been claimed that final-judgment appeals in (b)(3) were rare based on the assumption that, until Rule 23(f), parties would opt to settle instead of pursue further litigation if a district court certification decision involved damages classes under (b)(3). “If this dynamic were at play,” they write, “we would expect to see that (b)(3) classes are more likely to appear in appeals under interlocutory versus final-judgment review.”

Instead, the authors find that final-judgment appeals of certification decisions with respect to (b)(3) classes accounted for 33% of the decisions, with defendants bringing 40% of those appeals. “This casts doubt on the notion that parties are rarely willing to litigate through to final judgment once a district court has certified or declined to certify a [damages] class,” they write.

The authors further probe interlocutory appeals in relation to the decisions in Wal-Mart Stores v. Dukes and Comcast v. Behrend Noting that “prior to Wal-Mart, interlocutory appeals were far more frequently used to reverse grants of certification than to reverse denials,” they find the trend reverses after Wal-Mart, “and by 2017 reversal rates were comparable for grants and denials of certification by district courts.” They find a similar trend for final-judgment appeals.

Lastly, the authors explore the probability of a pro-certification outcome in cases with Democratic- versus Republican-majority panels for decisions published from 1970–2017. The gap between such panels narrowed from the mid-1970s to late 1990s, but then widened around the same time Rule 23(f) went into effect. They find that this widening gap corresponds with their previous research, which concluded that, since the mid- to late-1990s, “there was a growing focus in the Republican Party on restricting opportunities and incentives for private civil actions in general, and class actions in particular,” “Supreme Court justices became more polarized along ideological lines in their voting on Rule 23 issues,” Republican legislators introduced more anti-class action bills, and conservative activists boosted efforts to curtail class actions.

Yet, surprisingly, the gap between Democratic- versus Republican-majority panels began to close somewhat from 2011 to 2017, “when in the posture of making law, both Democratic- and Republican- majority panels were at their highest probability of procertification outcomes in the forty-eight years covered by the data.” They add that this occurred during an era when “both Wal-Mart and Comcast were governing law.” Still, even while both parties grew more pro-certification, Democratic- and Republican-majority panels remained polarized.

The authors conclude by writing that, “this temporal pattern of polarization is similar to what we found in earlier work on the Supreme Court in private enforcement cases in general, and in Federal Rules cases in particular. In the statistical models, we observe that party has a larger effect in interlocutory appeals (the gap between Democratic and Republican-majority panels is larger). Thus, the growing number of interlocutory appeals under Rule 23(f) in the 2000s contributed to the polarization we document. In this sense, one consequence of Rule 23(f) was to inject more ideology into class certification on the U.S. Courts of Appeals.”

5

STEPHEN B. BURBANK

ALGORITHM vs. ALGORITHM

CARY COGLIANESE

Edward B. Shils Professor of Law and Professor of Political Science and Director of the Penn Program on Regulation

In “Algorithm vs. Algorithm,” recently published in the Duke Law Journal, Coglianese and Alicia Lai L’21 tackle a key choice increasingly confronting governmental decision-makers: when to automate administrative tasks. They frame this choice as fundamentally one between the use of digital algorithms — such as artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning — versus the continued reliance on the existing algorithms that constitute human decision-making.

Humans “operate via algorithms too,” write Coglianese and Lai, and these are reflected in status quo governmental processes — including existing administrative procedures.

In this pathbreaking article, Coglianese and Lai offer a framework for determining when government should choose digital algorithms over human ones. Although they caution that “public officials should proceed with care on a case-by-case basis,” they also argue that decision-making about AI ought to be predicated on the acknowledgement “that government is already driven by algorithms of arguably greater complexity and potential for abuse: the algorithms implicit in human decision-making.”

Human algorithms are susceptible to many the same problems as digital algorithms, they write, and “will in some cases prove far more problematic than their digital counterparts.” Digital algorithms can “improve governmental performance by facilitating outcomes that are more accurate, timely, and consistent,” they argue.

Limitations of Human Algorithms

Coglianese and Lai review the range of physical, biological, and cognitive limitations that afflict human-decision-making. These include issues with memory, fatigue, aging, impulse control, and perceptual inaccuracies.

Human bias in various forms can also “lead to systematic errors in information processing and failures of administrative government,” write Coglianese and Lai. While training programs and other attempts at “debiasing” humans may counteract some of these problems, it is not always possible to remove errors and biases completely from human decision-making, they note.

Some of the examples they provide of biases embedded in human “algorithms” include:

• The availability heuristic: that is, “the human tendency to treat examples which most easily come to mind as the most important information or the most frequent occurrences”;

• Confirmation bias: or, “the tendency to search for and favor information that confirms existing beliefs, while simultaneously ignoring or devaluing information that contradicts them”;

• Anchoring effects: by which decisions can be skewed by how questions are framed or selective information is provided;

• System neglect: which often occurs when individuals make decisions in isolation “with insufficient regard to the systemic context”;

• Present bias: or the undue discounting of the future, which can also be related to loss aversion;

• Susceptibility to overpersuasion: which occurs when people are “persuaded by superficial, even irrelevant” appeals; and

• Racial and gender discrimination: which can manifest either as explicit animus or implicit but deeply ingrained biases.

Coglianese and Lai show how these individual human tendencies that negatively affect governmental decision-making.

They also note that, when it comes to making group decisions within organizational settings — as frequently occurs within government — humans succumb to a variety of well-documented collective dysfunctionalities, such as groupthink and free-riding, among others. These problems also too often impair governmental decisions, Coglianese and Lai explain.

The Promise of Digital Algorithms

Coglianese and Lai extol the potential advantages of using digital algorithms in governmental processes by noting their importance to “nearly every major advance in science and technology” in recent years.

Machine-learning algorithms, they write, are often grouped into two categories: “supervised learning,” which are provided with labeled data, and “unsupervised learning,” which can learn without labeled data. While humans are necessary to establish AI processes, machinelearning algorithms otherwise can operate autonomously. They “largely design their own predictive models based on existing data, finding patterns in the data that can be used to generate predictions that are quite accurate,” write Coglianese and Lai.

Machine-learning algorithms have become increasingly attractive in both the private and public sector because of benefits that “might even be characterized as inherent to digital algorithms” — accuracy, consistency, speed, and productivity.

Coglianese and Lai are quick to point out that this does not mean that machine-learning algorithms will always be better than human algorithms. They argue that the choice is always a comparative one: that is, one of a digital algorithm versus a human one.

They note the strengths of each type of algorithm. Digital algorithms can provide consistency and speed, while the human mind

6

on research by

“is well-suited to making reflexive, reactionary decisions in response to sensory inputs.”

Coglianese and Lai discuss a growing body of research that has “compared machine-learning algorithms’ performance with status quo results and found improved performance in a variety of distinctively public sector tasks.”

Despite these results, worries persist about the use of machinelearning algorithms, especially about the possibility that they can be “too opaque and prone to bias.” Coglianese and Lai note that existing systems dependent on human algorithms, though, “do not necessarily compare favorably to machine learning” on these grounds.

“When it comes to bias, the issue again is not whether machinelearning algorithms can escape bias altogether, but rather whether they can perform better than humans,” they write.

Deciding to Deploy Digital Algorithms

In their article, Coglianese and Lai warn against human errors that can occur in designing and operating digital algorithms. They suggest that the necessary human element in the design and establishment of computerized systems may be digital algorithms’ biggest weakness. Still, they argue that digital algorithms can promise to make fewer mistakes overall — “if they are used with care.”

“The key is for humans to engage in smart decision-making about when and how to deploy digital algorithms,” write Coglianese and Lai.

To aid government officials in deciding between digital and human algorithms, Coglianese and Lai present three approaches for balancing different, often competing values involved in these decisions:

• Due process balancing: As articulated by the Supreme Court in Mathews v. Eldridge, this approach “seeks to balance the government’s interests affected by a particular procedure . . . with the degree of improved accuracy the procedure would deliver and the private interests at stake”;

• Benefit-cost analysis: Under this approach, “machine learning would be justified . . . when it can deliver net benefits (i.e., benefits minus costs) that are greater than those under the status quo”;

• Multicriteria decision analysis: A variation of the first two, this last approach requires running through “a checklist of criteria against which both the human-based status quo and the digital alternative should be judged.”

Coglianese and Lai land on multicriteria decision analysis as the best and most practical approach for structuring administrative decisions about automation — and then they explain that the key question turns to which criteria should be used in coming to such a decision.

They acknowledge that the precise criteria to rely upon will vary according to each particular use case, but they explain that generally two types of criteria should be considered when deciding to digitize a governmental process. Specifically, these criteria are those related to the preconditions for the successful use of digital algorithms and the validation of improved outcomes from digital automation.

Coglianese and Lai write that, in addition to the need for adequate human expertise and computer technology, three main preconditions “can be thought of as a necessary, even if not sufficient, condition for a potential shift from a human- to machine-based process”: (1) goal clarity and precision, (2) data availability, and (3) external validity.

“Taking these three preconditional factors together,” they write, “machine-learning systems will realistically only amount to a plausible substitute for human judgment for tasks where the objective can be defined with precision, tasks that are repeated over a large number of instances (such that large quantities of data can be complied), and tasks where data collection and algorithm training and retraining can keep pace with relevant changing patterns in the world.”

On how to validate whether machine learning in fact improves outcomes, Coglianese and Lai identify three general types of impacts that should be tested: (1) goal performance, (2) impacts on those directly affected by an automated system, and (3) impacts on the broader public.

Coglianese and Lai emphasize the importance of agency officials carefully thinking through their decisions to digitize. Failing to do so “can have real and even tragic consequences for the public” as well as open the agencies up to public controversy and litigation.

The article concludes by offering readers three principal strategies for making sound decisions about putting digital algorithms into place: planning, public participation, and procurement provisions.

Coglianese and Lai conclude that “agency officials should take appropriate caution when making decisions about digital algorithms — especially because these decisions can be affected by the same foibles and limitations that can affect any human decision.” They conclude that “officials should consider whether a potential use of a digital algorithm will satisfy the general preconditions for the success of such algorithms, and then they should seek to test whether such algorithms will indeed deliver improved outcomes.”

“Algorithm vs. Algorithm” is one of the latest of a series of articles that Coglianese has authored or coauthored on public sector use of artificial intelligence, including “Regulating by Robot: Administrative Decision-Making in the Machine-Learning Era,” “ Transparency and Algorithmic Governance,” “Administrative Law in the Automated State,” and “AI in Administration and Adjudication.” A more complete collection of his work on artificial intelligence can be found online within the Penn Carey Law scholarship repository.

“With sound planning and risk management, government agencies can make the most of what digital algorithms can deliver by way of improvements over existing human algorithms.”

7

CARY COGLIANESE

ESG PROMISES

on research by JILL E. FISCH Saul A. Fox Distinguished Professor of Business Law and Co-Director, Institute for Law and Economics

As the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) movement movement continues to expand, Fisch has collaborated with co-authors Quinn Curtis (University of Virginia) and Adriana Z. Robertson (University of Toronto) to conduct a cutting-edge empirical analysis of ESG mutual fund behavior, presenting valuable data to regulators who are increasingly concerned with this sector. “Do ESG Mutual Funds Deliver on Their Promises?” was published in the Michigan Law Review.

The Rise of ESG Mutual Funds

Calls for corporations to be held accountable for the ways in which they contribute to climate change, racial and gender inequity, and supply chain human rights issues have contributed to the rise of the ESG movement.

Investments in mutual funds incorporating ESG criteria have grown significantly, prompting discussion on what it means for a fund to be designated as “ESG” as well as whether such ESG funds charge investors higher fees or deliver lower performance. A broad lack of clarity has raised many concerns, and regulators have signaled interest in enacting rules that would target ESG investment options, ostensibly to protect investors from risks such as greenwashing, inferior performance, and investor confusion.

Regulatory Pressure on ESG Funds

Both the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Department of Labor (DOL) have taken initial steps toward more stringently regulating ESG investing.

The SEC has expressed concern that funds with names that signal “green” or “environmental” practices might potentially be giving investors a false impression of their sustainability. Accordingly, in 2020, the agency requested public comment regarding updates to its existing “Names Rule,” which sets standards for the use of certain words in funds’ names. Among the issues on which the SEC requested comments was the Names Rule’s application to ESG funds. Subsequently in May 2022, the SEC proposed amendments to the Names Rule that expand the scope of the 80% policy required by the rule. The SEC also proposed amendments to its regulation of investment companies and investment advisers concerning funds’ and advisers’ incorporation of ESG factors. Among other things, the proposal would create a distinctive taxonomy of funds based on their incorporation of ESG factors.

Participant-directed retirement accounts, such as 401(k)s, are among the largest holders of mutual funds and subject to complex regulations under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) and DOL. Under ERISA, employers must uphold

“[W]hen faced with a critique of ESG funds, regulators should ask first whether there is an empirical basis for singling out ESG funds or if the purported ESG issue is one that affects the entire fund market.”

8

JILL E. FISCH

fiduciary duties and act “solely in the interest” of plan holders when making investment decisions. In recent decades, the DOL has issued increasingly specific guidance regarding a fiduciary’s decision to incorporate ESG factors, guidance that has shifted in accordance with the political values of the administration. Most recently in 2020, the DOL adopted a rule that specifically prohibited fiduciary agents from sacrificing any potential return on investment for non-pecuniary purposes such as ESG. Subsequently the Biden administration announced its intention to not enforce the rule.

These regulatory initiatives have focused their attention on ESG mutual funds and are motivated by the perception that such funds offer distinctive investor protection concerns. This proposition can be empirically tested.

Empirical Analysis

The authors constructed several categories of ESG funds, based on funds’ use of names that suggested a focus on ESG criteria and a list of ESG funds compiled by Morningstar. The authors compared these “ESG” funds to the rest of the mutual fund industry on the basis of their respective holdings, voting practices, costs, and performances.

In evaluating the extent to which an ESG fund’s portfolio differs from that of a non-ESG fund, the authors incorporated ratings from four leading ESG rating providers to construct a fund portfolio’s “ESG tilt.”

The analysis revealed that ESG funds tended to have portfolios with higher ESG scores than non-ESG funds. In examining low scoring ESG funds under the four different ESG measures, the authors found that only two “failed” each of the four tests. Even then, the authors note that the funds’ prospectuses divulged that those funds were intended to be “impact funds,” making it “unsurprising” that the funds invested in companies with lower ESG scores, as the aim was to increase those companies’ approach to ESG criteria over time.

The authors also investigated whether ESG funds generally vote their proxies differently than non-ESG funds. Using data from the ISS’s Voting Analytics database, the authors compared the voting behavior of ESG funds with that of non-ESG funds. As with portfolio composition, the analysis revealed statistically significant differences.

“Although our results do not speak to the question of whether ESG funds vote against management or in favor of shareholder

proposals ‘enough,’ there is compelling evidence that they vote differently from their peers and that a typical ESG fund’s mission involves voting policies as well as stock selection,” the authors write.

Critics have voiced concerns over whether ESG investments incur greater costs or yield lower returns than non-ESG investments. The authors assessed cost in two ways, inquiring whether (1) fees charged by ESG funds are higher than comparable non-ESG funds, and (2) whether the returns ESG funds offer differ systematically from those of comparable non-ESG funds.

Results indicate that ESG funds do not generally cost investors more in fees, generate reduced returns, or provide inferior riskadjusted performance. Funds that merely “consider” ESG principles incur a more complicated analysis.

Implications for Regulatory Policy

The authors’ empirical analysis, although limited to a specific time period, reveals “no glaring evidence of problems in the ESG space.” ESG funds are genuinely different from non-ESG funds and, despite these differences, do not appear to provide investors with an inferior investment option. As a result, the authors argue against ESG-specific regulations, concluding that “[t]he ESG sector of the fund market does not seem to be functioning worse than other parts of the mutual fund industry.”

More significantly, the authors reason that a variety of the concerns flagged by commentators — about investor confusion, higher fees, and the lack of a clear relationship between a fund’s name and its investment strategy — apply to a range of mutual funds, including growth, value, and industry-specific funds. Considering the findings outlined in this article, the authors recommend that, “when faced with a critique of ESG funds, regulators should ask first whether there is an empirical basis for singling out ESG funds or if the purported ESG issue is one that affects the entire fund market.”

In closing, the authors underscore that the results of their empirical analysis “provide no justification for regulatory invention,” and, moreover, “reveal[] that ESG funds do not currently present distinctive concerns [relative to other funds] from either an investorprotection or a capital-markets perspective.”

9

THE RUNAWAY PRESIDENTIAL POWER OVER DIPLOMACY

by JEAN GALBRAITH Professor of Law

by JEAN GALBRAITH Professor of Law

Galbraith breaks new ground in “ The Runaway Presidential Power over Diplomacy,” an article recently published in the Virginia Law Review. Especially in recent years, presidents have claimed an “exclusive” power over diplomacy as a justification for ignoring important congressional statutes — statutes that structure diplomatic engagement, ban appropriations for forms of international engagement, or require executive branch disclosure of diplomacy-related information. Although largely overlooked by scholars up to this point, these claims have led to a significant expansion of presidential power. Galbraith analyzes and critiques these claims, arguing for a more modest understanding of presidential power over diplomacy.

The President’s Claims to Exclusive Diplomatic Powers

Though the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) considers the President’s “exclusive authority to conduct the Nation’s diplomatic relations with other States” to be a “well settled” matter of constitutional interpretation, Galbraith contends that such power is far from “exclusive.” She breaks down the overarching power of diplomacy into five interrelated powers, three of which include strong histories of Congressional involvement:

• The power to represent the United States abroad

• The power to recognize foreign nations

• The power to decide the content of communications

• The power to select and control agents of diplomacy

• The power to control access to diplomatic information

10

on research

In her analysis, Galbraith agrees that there is a strong argument for the power to represent the United States abroad to remain squarely with the executive branch. Moreover, in Zitovsky v. Kerry, the Supreme Court directly addresses and affirms that the President exclusively holds the power to recognize foreign nations. Nonetheless, that still leaves the extent of presidential exclusivity regarding the other three powers of diplomacy largely unsettled.

Historically, the judiciary has “only rarely” participated in the determination of diplomatic power —Zitovsky was not decided until 2015, and even then, Galbraith underscores that the Supreme Court only addressed a fraction of the overarching “bundle” of the powers of diplomacy.

“Without the courts, it is left to the political branches to sort out their respective powers. . . . [I]t creates a dynamic where the executive branch can always win if it really wants to,” Galbraith writes. “The executive branch is far better positioned than Congress both to articulate its legal positions and to implement them in practice.”

The executive branch’s advantage comes largely from its institutional capacities to assert and implement its powers. On the other hand, Congress’s capacity to “cast a powerful indirect shadow on the conduct of U.S. international engagement” arises from its abilities to enact legislation and make vital funding decisions that could complicate the executive branch’s claims to “exclusivity” in international issues.

Forgotten Constitutional Struggles for What Counts as Diplomacy

At the time the Framers drafted the Constitution, “diplomacy” was barely — if at all — a word in the English language. Reviewing the history of its use and application reveals notable fungibility that remains to this day. Significantly, contemporary OLC practices and documents tend to define “diplomacy” broadly.

“By defining diplomacy broadly for constitutional purposes,” Galbraith writes, “executive branch lawyers vastly enlarge the reach of the President’s assertedly exclusive powers over the content of U.S. international engagement, the agents who undertake it, and information related to it.”

In demonstrating that such a definition is “neither constitutionally predetermined nor conceptually mandated,” Galbraith sets forth four potential means of limiting the executive power of diplomacy, including:

• limiting the power to encompass negotiation rather than policy;

• limiting the power to only “political” rather than “technical” matters;

• tying the power to certain institutional actors within the executive branch; and

• limiting the power within the context of participation in international organizations.

Rethinking Constitutional Control Over International Engagement

In this section, Galbraith sets forth three doctrinal approaches to the distribution of the power of diplomacy: exclusive control to the executive branch; ultimate control to Congress; and an intermediate option, which she favors while acknowledging that such a path would still leave much unsettled.

An intermediate doctrinal approach to the power of diplomacy could include limitations in each of the four categories. Galbraith’s first suggestion is to narrow the concept of “diplomacy” to negotiation and not policymaking. She also suggests that diplomacy powers could be limited to only the President and those executive agencies that focus primarily on foreign affairs, thus “allowing Congress to control nondiplomatic agencies as they engage abroad similarly to how Congress can control them as a matter of domestic law.” Moreover, even in international contexts, Congress could mandate statutory reporting requirements as a tool for oversight much the same way as they do for domestic issues.

Importantly, Congress has several available strategy options to increase its involvement in diplomacy. Congress could emphasize its views on diplomatic powers; formalize its legal reasoning; invoke “soft power” strategies to raise the cost of diplomacy for the executive branch; and/or challenge the executive branch’s assumed “exclusive” powers in court. The final suggestion — involving the courts — carries both significant risk and opportunity for Congress, and Congress has several avenues to pursue a case, if it desired.

The thought leadership put forth in this paper is “important not only for its treatment of this fascinating and understudied issue but also for what it contributes to more general debates in constitutional theory and practice.”

Galbraith encourages future scholars to consider the multitude of different legal questions this scholarship both raises and helps to answer. For example, this research demonstrates the counterintuitive phenomenon that transparency can, at times, be used as a “tool of power rather than constraint,” pointing to the OLC’s practice of generating a record of low-stakes precedent to build “valuable legitimacy for major moves down the road.” Further, this research also serves as a useful scholarly reminder of the strong historical support of Congress’s legitimate claim to some portion of the power to engage in international affairs. Lastly, the work also underscores the complex intersection of administrative and foreign relations law — an increasingly relevant and impactful nexus of study.

In closing, Galbraith reaffirms that “[i]t is time for a better structural allocation of power.”

“Future administrations will need to decide whether they wish to make indefensibly broad claims of exclusive executive power or instead pivot towards a more nuanced stance,” she writes. “If the executive branch does not cede ground of its own accord, then Congress has tools at its disposal to bolster its constitutional authority over international engagement.”

11

“Both Congress’s traditional role in supervising agencies and the substance of these agencies’ work suggest that their international engagement should not necessarily partake of whatever exclusive powers the President holds over diplomacy and instead should be more subject to congressional control.”

TAKING DISABILITY PUBLIC

on research by

JASMINE E. HARRIS Professor of Law

In “ Taking Disability Public,” published in the University of Pennsylvania Law Review, Harris argues that strong privacy norms underwrite disability antidiscrimination law and policy. Preferences for protecting access to information about disability as a means of preventing disability discrimination, however, may actually prevent societal engagement with disability as a complex, socio-political identity and increase costs of compliance.

Disability as Private Conventionally, the prevailing associations with “privacy” are those of individual dignity and autonomy. Because legal doctrines and policies tend to conceptualize privacy as an individual concern, rather than a public interest problem, decisions to make disclosures and redress violations often remain with the individual. Both the rise of the public welfare system and state interest in its regulation have encouraged disability’s conceptual placement within the “private” sphere. Relatedly, the “medical model” of disability presumes a person is disabled by their own body, instead of by a lack of accessible public infrastructure, further emphasizing disability as an individual concern. Moreover, contemporary trends of the “optimized” workplace hinge on the idea of an “ideal worker” who performs the job in accordance with specific methods. This is challenging for employees who need accommodations to perform the same work in accordance with their individualized abilities. Further, because increased professionalization of human resources departments have afforded employees and their supervisors little discretion in making adjustments to accommodate for varying needs, employees with disabilities are often deterred from seeking and obtaining reasonable accommodations.

The Logic of Privacy

In describing why greater privacy could function as a prophylaxis for contemporary discrimination, disability antidiscrimination scholars put forth several theories.

Privacy law can be appealing in the context of antidiscrimination because it allows individuals to make their own decisions about self-determination and self-care, is easier to enforce than complicated disclosure regulations, and preemptively protects individuals. Moreover, privacy law can insulate people with less visible disabilities from disability discrimination that often manifests in harmful public scrutiny and prejudice. Additionally, maintaining disability privacy may help a person avoid algorithmic discrimination, which has grown in recent years as lawmakers have begun to use artificial intelligence to detect a person’s disability status and use it to monitor them and potentially exclude them from employment or enjoyment of public services and accommodations, believing that their disability creates a risk for society.

Further, contemporary antidiscrimination laws are highly imperfect and may not offer as much post hoc protection or meaningful remedies for post hoc discrimination that flows from disclosure of information about disability. Discrimination can be difficult to prove under laws that require proof of intent and causation. Privacy law, on the other hand, operates on a fairly straightforward factual inquiry of whether a defendant attempted to obtain protected information or had a duty to protect confidential information and failed to do so. Thus, for someone seeking a remedy for disability discrimination, privacy laws may offer blanket protection against inadvertent secondary disclosures of disability information.

Privacy Norms as Antidiscrimination Law

In the context of disability, different areas of the law “nudge” privacy by explicitly requiring secrecy, accepting the negative valence of disability as a “fact,” and by emphasizing the law’s role in remedying harmful disclosure.

Many disability adjudications happen in informal settings with little or no public access, for the purported reasons of preventing embarrassment and stigma. In many of these non-public proceedings, it is not even required for the person with the disability to be present, and official records are not available to review on legal databases or through public requests.

Across several scenarios, education law discourages disclosure of disability information beyond a strict “need to know” basis.

“[O]ften, schools use privacy laws as a sword to enforce social norms of disability as deficient and stigmatizing, or, paternalistically, in the best interests of young people to protect them against longterm risks associated with these social norms,” Harris writes.

In the context of disability, tort law is used to protect against and remedy the harm that comes from an unintended disclosure of a “private” fact, such as one’s disability status. This paradigm reinforces the idea that one’s disability is inherently negative information. Harris uses LGBTQ+ history to draw parallels between tort law’s treatment of LGBTQ+ identities as legally private facts and broader social oppression.

The Costs of Privacy

Our collective overvaluing of privacy has made it impossible to accurately measure societal disability — especially disability that is not “visible.” This has led to many misconceptions about disability, including false notions about its prevalence and homogeneity.

Particularly in the employment context, privacy in the context of disability often hurt people with disabilities and prevent them from securing work because employers fear potential liability. For example, empirical studies have shown that when job applicants choose to leave resume gaps unexplained, employers tend to be less likely to hire them on account of the ambiguity — so, although people with disabilities are not legally obligated to disclose their disability to their employer, non-disclosure often comes with significant risks.

Additionally, for a person with a disability who seeks benefits such as workplace accommodations, the ADA creates a “‘double bind,’” requiring the person to demonstrate both that they are qualified to

perform essential functions of a job and that they are “substantially” impaired. Not only does this exacerbate the binary understanding of disability as being either unreal or vastly incapacitating, but it also encourages employees with less visible disabilities to attempt to self-accommodate or “pass” as non-disabled to avoid getting stuck between the law’s conflicting requirements.

The Value of Publicity

“Outside of disability law, several privacy law scholars have moved away from a narrow framing of privacy as purely an individual right to self-determination by recognizing public interests at stake in the production and circulation of information,” Harris writes. “These discussions among scholars can help us better understand why some degree of privacy must exist in the context of disability identity and status but, perhaps most relevant to the disability space, why privacy is not absolute nor simply a matter of individual choice.”

Privacy, some scholars argue, functions not only as a private right but also as a public good, as it is difficult for any individual to have privacy without all individuals having a similar minimum level of privacy. In all, Harris argues that privacy discussions in the context of disability must be contextual and nuanced.

On the other side of privacy, publicity values offer crucial opportunities to reform social norms around disability. Embracing disability as a public issue can help to create a more inclusive society wherein people with disabilities can occupy the sociopolitical identity of having a disability without shouldering the burden of that identity on a solely individual basis.

Harris sets out a series of recommendations as to how to make disability more visible, beginning first with the need to collect more data on the impact that contemporary disability laws and policies have on society. Moreover, social science indicates that the workplace and higher education are the most impactful places wherein people with less visible disabilities can “come out,” thus suggesting that targeting publicity efforts in those two environments may offer the greatest opportunities to change social norms. Finally, Harris suggests alterations to threshold questions that categorize people as “disabled,” stronger discrimination protections for those who choose to disclose their disabilities, and procedural shifts in the burden of proof and persuasion in disability litigation.

13

“Taking disability public requires a nuanced approach that surfaces the values and risks associated with legal designs that privilege privacy.”

JASMINE E. HARRIS

THE FUTURE of AMERICA’S HEALTH INSURANCE

on research by ALLISON K. HOFFMAN Professor of Law and Deputy Dean

Hoffman’s “How A Pandemic Plus Recession Foretell the Post-JobBased Horizon of Health Insurance,” published in the DePaul Law Review, describes problems that arise with a U.S. health insurance system overwhelmingly comprised of job-based coverage. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted these problems, when hundreds of thousands of people lost their jobs — and, in turn, health insurance — during a health emergency. Hoffman predicts that recent events could herald in significant shifts in the way the U.S. organizes and regulates health insurance.

The History and Present State of Job-Based Health Insurance

About half of all Americans are covered by employer-sponsored health insurance (ESI), which has been the dominant source of U.S. health care coverage since the twentieth century.

Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, job-based health insurance accessibility and affordability were declining. Not only were fewer employers offering health insurance to their employees, but among those that did, the cost to both employers and employees continued to rise.

First, the number of people working in non-traditional arrangements, such as 1099 or “gig” work, has increased in recent years. Though measuring this data poses challenges, much of this work tends to be structured in ways that does not obligate the employer to provide benefits, such as health benefits.

More critically, many employers, including large corporations, increasingly express frustration at healthcare’s rising costs and their diminishing power to negotiate for prices. Recent data from a survey conducted by a nonprofit organization that represents some of the largest employers and the Kaiser Family Foundation show that employers heavily favor greater healthcare regulation, such as stronger antitrust measures, more price transparency, government price caps, and even perhaps Medicare expansion.

What COVID Revealed About Having Health Insurance Tied to Work

“Because of the high costs and stakes of COVID-19 care, the federal government and states scrambled to try to keep people insured even as they lost jobs and to provide access to testing and some medical care even if not insured,” Hoffman writes. “The patchwork of policies enacted to pursue these goals perfectly captures the overly complicated healthcare financing system in the United States.”

While several pieces of legislation focused on ensuring that COVID-19 testing and vaccinations remained free regardless of insurance coverage status, COVID-19 treatment was less regulated.

About two to three million people became uninsured between March and September 2020. Though this is a high number, it is only a fraction of the number of people who became unemployed during this timeframe, in part because of efforts by policymakers and companies to keep people insured. For example, legislation and voluntary efforts by employers allowed some employees to retain their health insurance during a temporary or permanent job loss. Others who lost jobs were able to enroll in Medicaid or plans through the Affordable Care Act marketplaces. For those who remained uninsured, the costs of COVID could be overwhelming (the average charge for someone hospitalized with COVID-19 was by one estimate $43,986 and for ICU patients using mechanical ventilators, $198,394).

The initial policy response included the Trump Administration’s extension of the use of COBRA, which enables people to retain health benefits after losing a job, and Congress’s passage of the Families First Act, which discouraged States from restricting Medicaid enrollment requirements and provided $64 million to the Indian Health Service. The Biden Administration added to these efforts by making it easier for people to sign up for ACA marketplace plans, though a special enrollment period increased subsidies to buy coverage.

The Future Horizon of Health Insurance

These pre-pandemic and pandemic experiences have illuminated the benefits of moving away from job-based health insurance. Even more, employees may prefer to disentangle work from healthcare to prevent their employer from accessing private healthcare information, and employers may prefer to divorce healthcare from work to avoid tension with employees regarding what types of claims plans cover. Additionally, separating healthcare from employment may also grant individuals greater flexibility in pursuing entrepreneurial and other non-traditional career paths.

Admittedly, the transition away from job-based health insurance will be challenging in large part because of the lack of political support for any one solution.

14

Proposals for the Post-Job-Based Horizon of Health Insurance

1. Remove the ACA Firewall Between Group and Nongroup

Coverage

One solution experts suggest is removing the ACA “firewall” that encourages people to enroll in their employer’s plan rather than an individual plan under the ACA. Hoffman writes that this solution would especially assist low-income people who qualify for higher subsidies.

2. Voucherization of Health Insurance

Individual Coverage Health Reimbursement Accounts (ICHRAs), which allow employers to make pre-tax contributions to individual coverage plans for employees, offer another alternative. Small companies and companies with sicker workforces can use ICHRAs to avoid shouldering too much risk; however, plans individuals obtain using ICHRAs may not be as good as job-based health plans.

3. Medicare for All

A Medicare for All (MFA) plan would involve moving everyone to public Medicare coverage, creating one streamlined, single-payer system. Hoffman writes that “many experts have estimated that this plan, which would leave no one uninsured or underinsured, would result in little or no growth in national healthcare spending.” To combat risks associated with the inevitable disruption to America’s finance systems, advocates have suggested longer “phase-in” transition periods. Yet, this option is politically the most challenging.

“[T]he goal is a policy that simultaneously offers an alternative to employer plans in the short term and builds a foundation for a more equitable and efficient health insurance system in the long term,” Hoffman writes.

Not only would this solution lessen employers’ stressful involvement in the healthcare business while still providing their employees with health benefits, but it could also save employers money. The co-authors describe that such a plan would be voluntary — employers could elect whether it was beneficial to participate. Moreover, it would be possible to integrate employer contributions and ACA-style subsidies in a way that might expand coverage to people who could not previously afford their share of the cost of their employer plans or who are less often offered coverage through such plans, such as part-time or gig workers.

Importantly, premiums paid by employers and employees would help finance the employer public option, rendering it more broadly politically palatable than MFA. Further, this proposal may even fit into Byrd Rule limitations, meaning it could pass the Senate in a budget reconciliation bill.

Overall, COVID-19 did not create, but did expose, a myriad of flaws intrinsic within America’s current health care financing system. Hoffman urges policymakers to think deeply about the need for reform.

4.

A Public Option for Employer Health Plans

Finally, Hoffman worked with scholars Howell Jackson and Amy Monahan to develop a new proposal for an “employer public option” that would allow employers to enroll all members of their health plans to a Medicare-based public option.

“This system no longer serves many people well during the best of times, and even less so during a public health crisis,” Hoffman writes. “With these shortcomings in such clear relief, it is an ideal time to begin to invest in policies that can foster a more secure, less complicated, and more equitable post-pandemic horizon of health insurance.”

15

“[I]t is an ideal time to begin to invest in policies that can foster a more secure, less complicated, and more equitable post-pandemic horizon of health insurance.”

ALLISON K. HOFFMAN

LONGER TRIPS TO COURT CAUSE EVICTIONS

“Controlling for census tract characteristics and residence type, we find that excess commuting time increases default rates.”

on research by

DAVID HOFFMAN William A. Schnader Professor of Law and Deputy Dean

In the first controlled study of eviction rates across time in a large urban center, Hoffman and colleague Anton Strezhnev of the University of Chicago found that Philadelphia tenants who live further away from the city’s courthouse and rely on mass public transit are more likely to fail to show up, leading to eviction by default. In “Longer Trips to Court Cause Evictions,” Hoffman and Strezhnev report their findings that excess commuting time increases default rates.

The study reviewed nearly 235,000 evictions filed against approximately 300,000 Philadelphians from 2005 through 2021. Using datasets obtained through the non-profit Philadelphia Legal Assistance (PLA), the Pew Charitable Trusts, and elsewhere, Hoffman and Strezhnev found that 40% of tenants in eviction proceedings during that period lost due to default.

Like many cities across the nation, Philadelphia continues to suffer from an ongoing eviction crisis; Hoffman and Strezhnev write that because commuting time is plausibly unrelated to other causes of eviction, policymakers may consider it as an instrument to better identify how eviction causes downstream social problems and prevents disadvantaged people from flourishing.

Preliminary Considerations and Findings

Hoffman and Strezhnev found it “surprising that although policymakers describe defaults as a part of the eviction crisis [in Philadelphia], we lack information about their incidence across jurisdictions.” Accordingly, the authors set out to explore questions such as “How many defaults are there, really? Do they lead to evictions? Who fails to show up, and why? And given the shock of Zoom justice wrought by COVID-19 in eviction court, did making justice remotely accessible matter to outcomes?”

According to the calculations of Hoffman and Strezhnev, for every 10 minutes in additional commuting time, tenants are between .65 and 1.4 percentage points more likely to default. A one-hour increase in commuting time has a 3.9 to 8.6 percentage point average effect on the probability of tenant default. Were all tenants to be able to get to their hearing in 10 minutes or less, Philadelphia would have eliminated approximately 4,000 to 9,000 such evictions due to default during that time.

“Controlling for census tract characteristics and residence type,” write Hoffman and Strezhnev, “we find that excess commuting time increases default rates. This effect holds when comparing properties owned by the same landlord, when controlling for direct distance to the courthouse, and even when controlling for commuting time measured during the weekend.”

In contrast, when tenants were offered Zoom or virtual hearings during the COVID-19 pandemic, the commuting time effect disappeared. The result is also absent for tenants in public housing, whose eviction processes are laxer and are not built around defaulting those who show up to court late.

Moreover, Hoffman and Strezhnev also found that “petitions to reopen defaults are rarely filed and infrequently granted.”

16

Materials and Methods

From PLA, the authors obtained 339,172 eviction documents involving residential properties from January 2005 through July 2021. Hoffman and Strezhnev filtered the dataset to include only properties from which they could “unambiguously parse and address number and street name from the text of the listed address and obtain, from Google Maps API, a correctly matching address with a latitude and longitude.”

For demographic covariates of concern — namely, the socioeconomic characteristics of different Philadelphia neighborhoods — the authors gathered median income and median contract rent from the 2015 American Community Survey; they used 2010 census block-level data for racial demographics.

Landlord data presented a unique problem that required a creative solution. “Because the docket often only lists the filing LLC as the plaintiff, and since individual landlords may own multiple properties through different LLCs, we would be unable to identify common landlords across eviction proceedings without additional data.” Accordingly, to obtain landlord data, Hoffman and Strezhnev used a novel database of Philadelphia landlords obtained through an agreement with the Pew Charitable Trust to match roughly 55,000 landlords to 136,000 rental properties.

The authors’ primary independent variable of interest was, of course, the commuting time to the Municipal Courthouse. For this determination, they queried the Google Maps Distance Matrix API to determine the estimated distance and travel time between each building in the dataset and the Philadelphia Municipal Courthouse. They measured the time and distance to the courthouse using public transit on a weekday (when hearings are scheduled) and on the weekend.

Upon extracting the outcome of the proceedings from the docket, Hoffman and Strezhnev landed on a dataset of 223,840 eviction proceedings across 61,104 unique buildings and 283,812 unique named defendants. The plurality of judgments were in favor of the landlord and nearly all were defaults, with the second most common outcome a settlement between the parties, and the third most common withdrawal of the case by the landlord.

In non-public housing (non-PHA) cases, default rates varied over time and space with the earliest period of 2005 to 2010 having the highest rate of 40%. The data showed a steady decline in that

number over time, though, which coincided with the imposition of new landlord regulations that increased the costs of filing frivolous evictions. In public housing cases, default judgments accounted for about 20 to 25% of evictions and showed no similar pattern of decline. “Because those evictions are so distinctive,” wrote Hoffman and Strezhnev, “for our primary analysis, we focus on non-PHA cases.”

In addition to the main text, the authors provide an impressive amount of supplementary information that includes discussions and analyses of data pre-processing, sensitivity analysis, the frequency of reopening default judgments, weekday vs. weekend commuting times, effects of commuting time on judgments by agreement and complaint withdrawals, absence of seasonality in treatment effects, and regression tables for the main text results.

Finally, the authors replicated their findings using a dataset of over 800,000 evictions from Harris County, Texas. They used data accessed through the Eviction Lab and “found results extremely similar to Philadelphia, despite the radically different jurisdictions.” Since mass transit is largely unavailable in that location, the authors focused on the relationship between driving time (to the local justice of the peace office) and the likelihood of eviction. They found that a 10-minute increase in driving time resulted in an increase in the likelihood of default by 3%. Even when comparing evictions taking place in the same building, in the same month, but which are assigned to different courthouses, defaults are more likely in the courthouse that is further away.

In conclusion, Hoffman and Strezhnev find that their results “indicate that policymakers should consider the distributive effects of rules which forfeit legal rights conditional on showing up to the courthouse at a particular time.” They suggest that alternatives “from remote hearings, to easy rescheduling, to no-excuse reopening” are not only available but would also “reduce the incidence of this pathologic practice.”

Turning to the legal academy, the authors encourage scholars to consider whether other legal proceedings are similarly impacted by transit. “Essentially, we highlight the role of physical place in producing access to justice. And our results may offer a novel and better identified tool to study the downstream effects of evictions.”

17

DAVID HOFFMAN

THE INVENTION of ANTITRUST

In “ The Invention of Antitrust,” published in the Southern California Law Review, antitrust expert Hovenkamp offers a thorough analysis of the shifting economic, political, and judicial tides from the late nineteenth century to the middle of the twentieth century that formed the foundation of antitrust law as we know it today. He makes the case that Progressive Era reformers pushed approaches to market intervention to the left, even as boundaries and structures were still being defined, leading to an extended neoliberal correction that emerged in the reaction to the New Deal.

In the first three decades of the twentieth century, policymakers “invented antitrust law,” Hovenkamp writes. “In fact, after decades of experimentation we are reclaiming much of it.”

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 and the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 were accompanied by a Progressive antitrust movement that was “both political and economic,” reflecting growing concerns about industrialization, the labor movement, consumer power, and the evolution of distribution in an era of technological advancement. In this turbulent economic environment, marginalist economics and industrial organization theory offered competition analysts new tools to assess the marketplace.

Hovenkamp refutes the notion that the Progressives were focused only on size in their antitrust efforts and ignored the opportunities it created. United States Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, for example, was an advocate for scientific management and its beneficial effect on pricing. The response to the growth of trusts was, instead, based in concern that exclusionary practices would be a vehicle for achieving and sustaining higher prices and cementing market dominance.

The Chicago Conference on Trusts

The emerging trust problem was addressed at the Chicago Conference on Trusts in 1899, “an exceptional window into the contemporary mindset,” Hovenkamp writes. Its attendees, which included politicians, economists, lawyers, social scientists, business and labor leaders, insurers, and even clergy, represented every interest group with a stake in policy regarding trusts. Opinions about the treatment of trusts naturally varied widely, but “the strongest consensus around a single view was that the trusts should be controlled by changes in corporate law.”

Following the conference, Hovenkamp writes, “Progressives began to focus more narrowly on the antitrust laws and the discipline of economics as the preferred tool for dealing with the trusts.” Political and moral rhetoric has always been present in the conversation around antitrust, as the conference laid clear, but it failed to serve as a policymaking guide.

Marginalist Economics and Market Revisionism

As Hovenkamp emphasizes, “one cannot understand the set of tools that the Progressive antitrust policy makers deployed without understanding their underlying economics.” And by the 1930s, nearly all economists were marginalists, an “undervalued” movement in the history of antitrust. Marginalism offered a forward-looking perspective on value, placing it in the willingness to pay for the next, or “marginal,” unit of something. This served as a break from the classical view of value as being present in a good or the labor used to make it.

18

“Today antitrust policy sits between the aggressiveness of the Roosevelt Court on one side, which often condemned competitively harmless practices, and the decaying remnants of the Chicago School on the other.”

on research by

HERBERT HOVENKAMP James G. Dinan University Professor

Marginalist analysis presented new ways to quantify supply and demand, expanded the use of mathematics in economics, and undermined the classical view of markets as inherently competitive.

“As a result, marginalism began to make a broad and unprecedented case for selective state intervention in the economy,” Hovenkamp writes.

The shift toward understanding markets as a “created human institution,” rather than simply a product of nature, “was perhaps Progressive economics’ most important contribution.” The markets were increasingly viewed as a reflection of state policy and judged accordingly, and concerns about market coercion grew. Progressive law school professor Robert Hale gave voice to trepidation about the way markets could limit freedom, writing that prevailing economic systems were “permeated with coercive restrictions of individual freedom, and with restrictions, moreover, out of conformity with any formula of ‘equal opportunity.’” This view filtered into public law as well as into competition law, where it influenced a more aggressive approach to vertical mergers.

The development of partial equilibrium analysis, which Cambridge University professor Alfred Marshall borrowed from the science of fluid mechanics, allowed analysts to group firms producing similar products into discrete markets, making the analysis of market behavior “both tractable and useful.”

The focus on individual industries took over the field of business economics and shaped approaches to antitrust policy. Increasingly, regulation was seen as a “corrective for market failure” — those instances when ordinary market forces are insufficient in keeping an industry operating “tolerably well.” Over time, encouraged by the Great Depression, regulation expanded beyond this narrow framework to question whether markets can be trusted to remain efficient and egalitarian at all.

Among the reasons for doubt, Progressives identified pricing discrimination as one of the evils brought about by the trusts, and “most of the economic foundations for our understanding of price discrimination developed during the Progressive Era as an outgrowth of marginal analysis,” Hovenkamp writes.

Potential competition, which had been a “crucial” element in early antitrust analysis as a deterrent to monopoly pricing, “was natural and ordinarily to be expected,” the common Progressive position went. But under closer inspection, policymakers began to worry that “dominant firms could devise practices that would prevent or limit its operation.”

Working with all of these factors in mind, economists John Bates Clark and his son John Maurice Clark formed arguments that helped develop the basic model for antitrust that still holds today, requiring

a showing of “both monopoly power and anticompetitive practices,” Hovenkamp writes. Over time, issues of potential competition evolved into the modern doctrine of “barriers to entry” — “natural or fabricated obstacles” that stood in the way of competition, a term the Supreme Court first used in U.S. v. American Tobacco Co

Over time, as doubts grew about potential competition and its efficacy, assessing the number and power of a company’s actual competitors became more important. By the 1940s and 1950s, “relevant market” analysis was central to questions of market power in a rising tide of judicial decisions.