8 minute read

Does our pay for performance process deserve rewarding?

Does our pay for performance process

deserve rewarding?

COVID has awakened employees to what they really want from their employment, forced companies to view employee wellbeing as a priority, and challenged many of our prior beliefs about what motivates employees. We must step back and rethink our total reward strategies. We need to identify all of the rewards and benefits that employees receive or to which they have access. We need to design these to work together to produce the maximum impact. Employees need to be sufficiently and frequently advised about them, take them up, and be reminded of their value.

One of the most contentious components is Pay For Performance - often viewed as an essential component. But, from my nearly 40 years of HR experience it is often the weakest component. Here are some recurring reasons: 1. Even in our current difficult financial times, an increasing percentage of the working population are not significantly motivated by pay; 2. Focus on individual reward is not positively received in some cultures in our now global commercial world, often being viewed as divisive; 3. An increasing percentage of the working population are more concerned about fairness than personal gain; 4. Processes for determining individual performance-related awards typically consume excessive resources (time that

could be spent on strategic thinking, on addressing critical business issues, and on development) and emotional energy. They can last for weeks, often delaying planning for each upcoming period; 5. Most schemes are based on an unsubstantiated belief that because pay for performance feels right, that it must be effective.

There is even evidence that some are destructive; 6. The drive for simplicity has led to many Pay For

Performance schemes lacking comprehensive coverage of performance and sufficient specificity to support the level of precision and rigour that they demand; 7. Most performance assessments, on which Pay for

Performance is based, are of poor quality - lacking in validity, reliability, and comparability to name but three shortfalls. Moderation or calibration processes designed to address these often replace one set of biases with another. 8. In many cases, the difference between rewards to top performers and poor

Pay for performance is a staple of any rewards model, but practitioners often take for granted that it is sound. In fact, a good pay for performance model needs intensive planning and careful design By Clinton Wingrove

performers is insufficient to achieve any anticipated incentive. Yet when it is, it often created dissent.

What do we need to consider?

I am not against Pay For Performance. But, the design of Pay For Performance presents many opportunities and many pitfalls for us Human Resource professionals. Many questions need to be addressed, including: • Do we wish to recognise, reward, or provide an incentive for performance? Those are three different activities with different effects; • Why do we want to implement Pay for Performance? What do we believe it will do for the employees and thus for our organisations? • For which dimensions of performance do we wish to pay e.g., - What (outputs, results), How, or Growth? - Short term or long term? - Final, Cumulative, or Improvement? • Can we be assured of having comprehensive, valid, reliable, differentiating, comparable, and defensible measures of the chosen performance dimensions? This is notoriously difficult for knowledgebased and many other roles; • Does this fit with our declared values? • How do we want to balance company, team, and individual performance?

Company and team-based

Pay for Performance is far simpler to implement and more directly supports collaborative working. • How will the budget be derived, allocated, and then paid? Any ambiguity, uncertainty, or unpredictability risk suspicion and cynicism; • What might be the consequences of the scheme (employee reaction, union reaction, management commitment, local cultures, etc), and how will the system integrate with the other benefits packages? We need to consider both the employees and the managers as most schemes are highly dependent on the skill and commitment of the latter.

Many otherwise excellent schemes have failed to produce desired results simply because one or more such questions was either ignored or answered incorrectly. But the sheer commitment of resources most organisations have already made in their reward schemes activates the investment bias – “Given what we have invested in our scheme, we cannot scrap it now. Let’s invest a little more in refining it and I’m sure all will work better.” Will it; seriously?

What about the employees themselves?

The response of each individual to any scheme is greatly affected by them and their personal circumstances including but not limited to: • Their financial aspirations. Is the target employee pool working in a sector known for Pay for Performance? Do we specifically recruit people who are seeking high

financial rewards? Is pay the primary reward offered and generally low compared to competitors’ offerings? • Their personal financial security and horizon (the timeline over which they plan their cashflow). Is the target employee pool typically paid sufficiently well that they can think in terms of the period to which you wish to connect the rewards? • Their level of risk aversion. Is the target employee pool typically recruited because of their willingness to take risks, take personal accountability, and work independently? • Their discretionary finances. How big could any award be, compared to their typical discretionary finances? • Their ability to predict the award they might receive. What influence will each employee have over the measures set for them? To what extent will they be able to predict their award i.e., the return on their investment in the enhanced performance that we seek?

With the global decrease in trust in organisations, leadership, and management this has become a very significant factor.

The answers to the above questions should inform any design of a Pay for Performance scheme and how it addresses these three key issues: BUDGET: how much money will be allocated to the scheme;

ALLOCATION model: how will the budget be apportioned to the individuals;

APPLICATION model: how will the awards be paid. Budget

Before completing the design of any scheme, the question of how the budget will be determined needs to be considered. Will the scheme be funded by a predetermined sum of money, and, if so, how is this sum to be calculated? Or will the scheme produce a budget requirement and, if so, how will the factors that influence it be decided and what will be the final approval process?

Allocation model

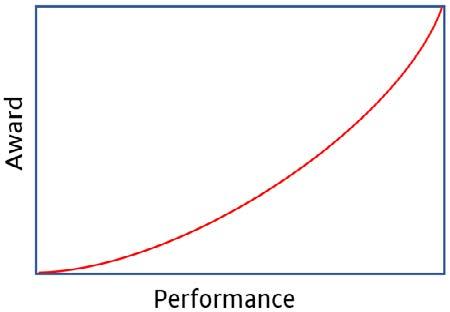

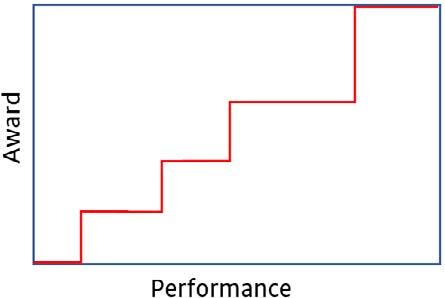

The objectives behind the scheme, and the existing base pay scheme will guide the determination of an Allocation Model: is it banded or continuous and what is the shape, as illustrated in the following diagrams?

If the objective is to reward and motivate individual ‘high fliers’, then the model will produce significantly higher awards for them.

If the objective is to provide an incentive for individual lower performers to improve (one of the most common intents), then there will be a sharp increase in

the size of the award for a small increase in performance at the lower end of the performance scale.

If the objective is to provide an equitable reward for performance, with continuous encouragement for improvement, then the model will be continuous and even.

Banded models are also possible, with performers being grouped based on their individual -performance. Such banding can be based on percentile (e.g., bottom 25%, next 10% etc.) or on actual performance (e.g. rating 0, 1-2, 3-4, 5-6 etc.). Application model

For individual Pay for Performance, there are four common ‘payment’ methods:

Base pay, where competency assessments may drive base salary to reflect the value of this proven ability/ asset.

Bonuses, where achievement of objectives may be used to drive one-off bonuses that reflect the value but potentially non-recurring nature of a contribution.

Share options, which may be driven by a combination of measures.

Access to special ben-

efits (e.g., funded learning and development), where development achievements may be used to trigger access to more expensive development resources to further capitalise on the individual’s potential.

The final model needs to ensure maximum equitability (payment versus performance) combined with optimum return on investment, and minimum risk/long term commitment for the company. Other considerations

Besides these, many less tangible factors have to be considered to address the wider context. These include: • What level of discretion will be needed for managers, to their commitment to and ownership of the scheme? • What other processes will influence pay management, and how? • What is the day-to-day performance management process and how will this ensure that the Pay for Performance scheme is effective? • What is the culture/climate of the company and its various locations, and will the scheme be compatible with those?

When we bake cakes, the quality of our cakes depends on the quality of the ingredients as well as the skill of us as chefs. As we move into an era during which TOTAL REWARDS become ever more significant, let’s not lose sight of the importance of ensuring that each INGREDIENT is well designed and fit for purpose. We may be great HR chefs but let’s not assume that the ingredients we already have in the cupboard, especially our Pay for Performance scheme, are up to standard!

Clinton WingrovE is the Principal Consultant, Clinton HR Ltd www.clintonhr.com