CALIFORNIA ART CLUB PRESENTS

May 11–July 28, 2024

ON LOCATION IN MALIBU 2024—the ninth in a triennial series at the Weisman Museum— celebrates the continued vitality of California Impressionism and plein air painting with all new works created by members of the historic California Art Club (CAC). This year’s exhibition, featuring more than 50 works of art, was juried by CAC executive director and CEO Elaine Adams, President Emeritus Peter Adams, and president Michael Obermeyer, with special guest juror Rick Gibson, senior vice chancellor at Pepperdine University.

In this roundtable conversation, moderated by Weisman Museum director Andrea Gyorody, the jurors discuss the history of the exhibition, the experience of painting in nature, and the new perspectives emerging in this year’s presentation.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

ANDREA GYORODY: Can we start by recounting a bit about the history of this exhibition at the Weisman Museum?

PETER ADAMS: The On Location in Malibu exhibition started off as an update or an alternative to an earlier exhibition that [late Weisman Museum director] Michael Zakian had put on. It had two historic painters, William Wendt and George Gardner Symons. They painted Malibu and the Rindge Ranch. There was a railroad there at the time too. These were historic paintings done more than a hundred years ago of the Malibu area. Michael came to us and said, “Why don’t we update the exhibition and put it in contemporary eyes?”

ELAINE ADAMS: Malibu has everything. There’s so much beauty. Dr. Zakian’s idea was to show how the beauty continues and that artists are still inspired by the area. In our first collaborative exhibition, he invited California Art Club artists to paint their interpretations of Malibu. From the more than 300 submissions, 65 paintings were selected for the exhibition. We just thought it was going to be a one-time show. But it was so popular, he said, “we want to do another show next year.” After that, it became a triennial. Here we are now in our ninth triennial exhibition, 27 years later. I think it’s a great tradition.

Plein air painting has been done for centuries. It’s just painting on location. It’s really California Impressionism but the quality of plein air painting has grown over the last couple of decades through the California Art Club. It’s because the artists come together and they push each other and make each other better and stronger, teach each other some techniques. The artists see something that another artist did, and they’re inspired.

These types of exhibitions help inspire the artists in their work and in developing skills, but they also educate the public about art, about their immediate community, and what it is that the artists are seeing that maybe we as mere mortals miss.

In plein air painting, it’s difficult to grasp a lot of information right in front of us and then edit it and decide what the main features are. What I enjoy is watching artists painting the same location and arriving at completely different interpretations, different techniques, different approaches. It’s because something caught that artist. Why is it important? It’s because the artists really connect with our world, who we are today. Even though plein air painting is a tradition, it’s different today than it was 100 years ago.

THE ARTISTS REALLY CONNECT WITH OUR WORLD , WHO WE

ARE TODAY.

MICHAEL OBERMEYER: As an artist from Orange County who can’t just venture up to Malibu after lunch, this show forces me and a lot of the artists who don’t live close to travel up to Malibu and spend a couple of days just exploring and painting. Sometimes I have something in mind, what I think I want to capture, but when I’m going to paint, I’ll go in early morning, spend the whole day and end up painting two or three completely different scenes and finding three or four more that I want to return to. I get inspired by the other painters every three years. I want to come up with an idea that’s maybe slightly different than the typical Malibu paintings and go off the beaten path a little bit and discover so much more about this whole area. Then I have three or four new ideas for three years from now.

RICK GIBSON: I worked with Michael Zakian on the first show in a role I had on the design team [at Pepperdine] as they worked on the catalogue. Michael and I talked a lot about this show, and one of the things that’s interesting is this idea that unlike, say, Laguna Beach, Malibu has always been hidden, off limits. It’s felt like that for a lot of people. That was the intent, I think, of a lot of people who lived here. It certainly was with Mrs. Rindge. She built the railroad as a legal loophole, as I understand it, because the state would not compel her to have a second railroad go through her property. To avoid that happening, she built a small railroad long enough for them to reroute around.

Malibu has always been mysterious. It’s been an enclave of people who like to keep to themselves. The mystery and the mythology around Malibu has always been of great interest. Michael liked being able to show that with these paintings, which were often very narrowly focused. It was like we were revealing Malibu’s secrets here and there.

AG: For this year’s exhibition, I’m curious to know whether there were specific tendencies that emerged in the submissions.

PA: I was absolutely surprised this year. I thought that a lot of the artists would mail it in, because this is the ninth time we’ve done this exhibition, they might have old paintings they could pull out. I was genuinely surprised at the variety of the artwork that came in. That one painting that was of the red fire scene with the firefighters, I thought, wow, that is really an interesting piece. We didn’t have anything like that. Then some of our top artists really pulled out some great works of art. Michael, you did, and Ray Roberts. I was generally delighted by the high caliber of work.

MO: Yes, I agree with Peter. I love the variety. I’m always looking for variety when I paint and when I’m viewing paintings. As Peter said, that fire scene, it was so expressive and unique. When you consider that Malibu has a history of fires and it’s never been captured in painting, at least for our show. It was unique and exhilarating to see, especially with the way the artist handled it.

RG: This is my first time to jury [an exhibition], so thank you for the opportunity. At baseline, we were looking for the quality of the work from composition to the mastery of technique, being able to create a sense of light in particular, which I think is critical to plein air painting. We were always asking and thinking about some of the mystery around the lighting.

We started as a baseline just with quality, and then we moved quickly to subject matter, and then beyond that, how it made us feel, how evocative and expressive it could be. One way or another they all began to tell an amazing story about the area.

PA: There were a few nocturnes in the exhibition that I thought were very interesting, the Jeff Sewell nocturne, then there’s one of Neptune’s Net. I thought that was an interesting piece because it’s so Malibu, so much a part of going up and down the coast.

AG: Michael, in your work in particular there’s built environment cutting through the landscape, as opposed to a kind of romantic, untouched view of nature. As we’re looking at these submissions together, built structures and interventions crop up in other works as well, and I wonder what you think about these two approaches.

MO: I think it’s important to capture Malibu in its current form. I paint here in Laguna Beach and I love all the paintings of Laguna where I climb around and paint and see how much it’s changed and evolved over a hundred years. I think it’s our responsibility, at least for me as a plein air painter, to dictate or record my surroundings as they are now. As beautiful as the coastline is in Malibu and Laguna, you can’t help but have this strip of concrete that winds down and all the development encroaching on the hills and it becomes part of what we know. This year both of my paintings [in the exhibition] are views of the city from the road and very familiar views if you ever drive around Malibu. To me, it’s a time and place. It’s a sense of 2024 Malibu.

Anna T. Kelly, Saving Malibu, 2021, oil on linen.

PA: So many of us have very strong environmental concerns and really love the open spaces so much. That’s probably one reason why there are a lot of wonderful landscapes and seascapes in the show that don’t have a whole lot of buildings in them. It’s a timeless quality in a sense, but in another sense, it’s wonderful to document the day and time that we live in. Michael, I know you do that very well and so do so many of our other artists. It’s nice to have both of those approaches in the show.

MO: It’s funny. I’m inspired by light. For me, the subject is always the light, whether it’s hitting a street or beach or an open meadow or a mountain. Like Peter said, I love being out in pristine, quiet outdoors where there’s no people, but I also love painting the city. Sometimes I’m so inspired by the open landscape. I’m wondering if I’m inspired just because they look like the paintings of the 1920s and ’30s. We were driving out to the desert yesterday, my wife and I, and there’s an area that’s just wide-open valley with hills, and there was this perfect haze. I said to my wife, “Oh, look at that. That is a painting to me. I want to pull over and paint that.” Then a minute later I thought, maybe it’s just because it looks like a Hanson Puthuff painting or a William Wendt. Maybe I’m just inspired because I want to try to copy what they were painting, and I’m going to fall short of that and be frustrated. Am I inspired just because it reminds me of old paintings, or am I inspired because I really think it’s beautiful? At the same time, I’m also inspired by driving down a busy boulevard with the light and haze and a distant hill as well.

AG: I love that observation. Of course Malibu is used as a set quite often, and it’s very hard to drive through this landscape without images from film and television in your mind as you are experiencing what’s in front of you. It’s not a raw, unmediated experience anymore because we’re so inundated with footage of this place. I wonder if you see that, Michael, reflected in the works themselves. Are you seeing the effect of that mediation, or the fact that these are views that many people have painted over and over again?

MO: Yes, I see that sometimes, or at least I think I see it. I can’t read the artist’s mind, but sometimes I’ll look at certain views that they’re painting, a certain beach or area, and I’m thinking, “Well, they painted that for the same reason I did, and it’s because that reminds me of when I was a child watching this TV show where they filmed it on that beach all the time.” It’s a beautiful beach, we all want to go there and capture it.

PA: I don’t think that many of us are now at the point where we’re trying to copy anyone else. We’ve all become our own artists.

Top to bottom: Jeff Sewell, Moonlight Mile, 2024, oil on board. Renae Wang, Dinner at Neptune’s Net, 2024, oil on panel. Michael Obermeyer, Highway One, Malibu, 2024, oil on canvas. Beverly Lazor, Peering Through the Pier, 2023, oil on linen.One thing that I really like about this exhibition is the different styles and the fact that a lot of these styles are the artist’s own style, not something that they’ve taken from someone else.

When an artist is out painting in nature, at least I, and I think most people, have a strong bond with what I’m painting. You’re there for two or three hours painting it, and you see the painting years later and you can remember the smells at that time. You can remember what you were thinking and the popular songs of the day. You become one with the scene that you’re painting. That’s not so true if you’re photographing it because that just takes a second.

If you’re there for a few hours working and struggling and trying to get this palm tree to look like a palm tree and get the fronds to look right, and also capture the sense of light, it’s an endearing experience that is not found in photography or really any other art form. That’s something that is wonderful about plein air painting. It brings you closer to the subject matter that you’re working on.

YOU BECOME ONE WITH THE SCENE THAT YOU’RE PAINTING.

MO: Oh, yes. Absolutely. I agree. For me, they’re more than paintings. They’re an emotional response to that three-hour period where you’ve just become so tunnel visioned, focused on what you’re painting and your immediate environment. Like Peter said, you can remember the smells, conversations people might have had as they were walking by. Just the feeling of that day that you can’t capture any other way. For me, those paintings become valuable personally. It’s a gift from that day that I get to take home.

EA: I like to think of these works as works of poetry and this feeling of self-expression from the artist. When you look at these, if you really think about them and remove the idea that we’re programmed to look at pictures as photographs, think on a deeper level. What is the key point of the work? Where is the artist taking me with this work? It’s really a personal journey between the viewer and the artist.

I look at accomplished plein air works as works of poetry and unique from other genres. Looking, for instance, at the Karl Dempwolf painting at Leo Carrillo, you can hear the ocean, you can feel the warmth on this hiker, you can smell the salty air. You don’t have to just look at the picture, you can put all your senses into this, the touch, the feel, the sound, everything goes into it.

RG: If we’re not careful, at least as I was looking at the art, plein air sometimes can feel a little sentimental in its approach. But I found that many of the paintings in this exhibition are hardly sentimental. They’re showing the power of the landscape itself, the power of water, for example. These are really powerful works. I don’t think there’s a single artist that thought, “Hey, I can improve upon nature here.” It was the opposite. It was, “How do I find a way to embrace what is so powerful?”

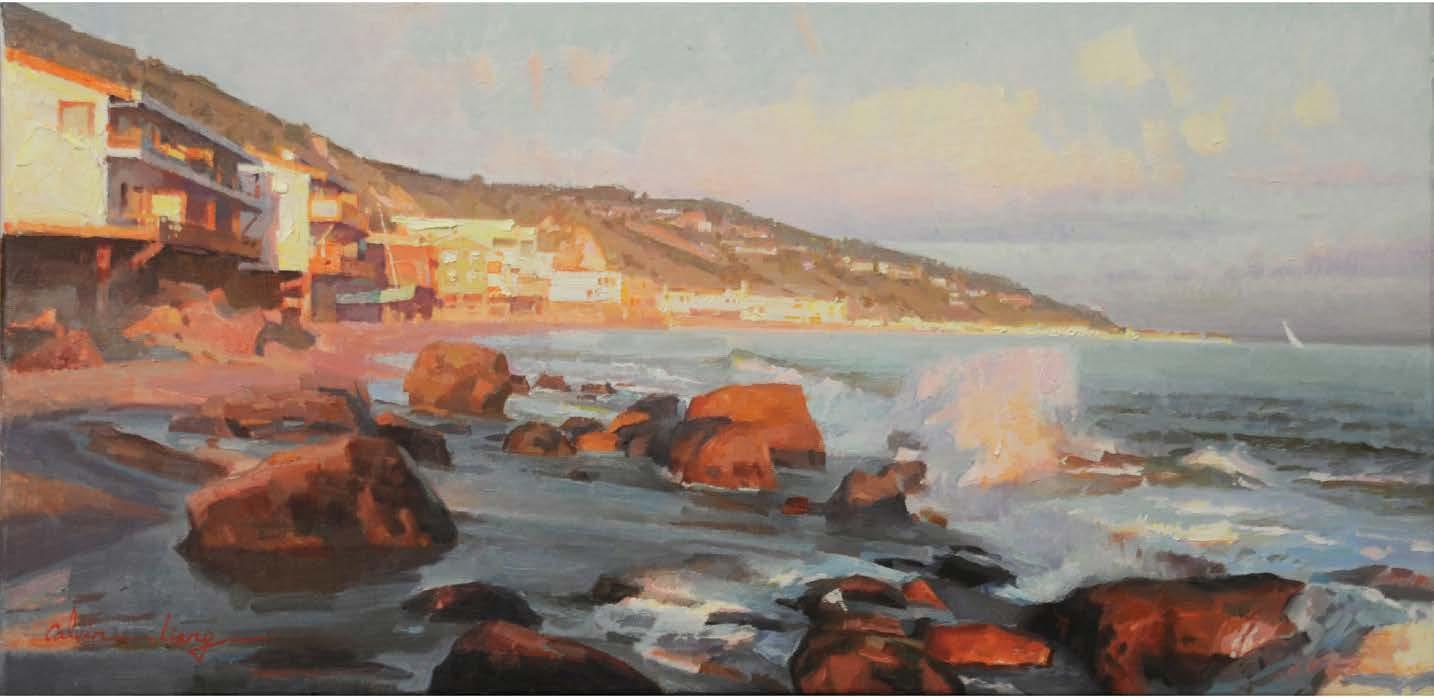

EA: In Peter’s seascape paintings, for example, the emphasis is on a split second in time, the fleeting relationship between the light and its effect on the ocean, sky, and rocks. The scene is constantly changing. The effects are changing.

Peter Adams, Afternoon Foam and Surf; El Matador Beach, 2022, oil on panel.

Right: Karl Dempwolf, The Crags, Malibu, 2024, oil on canvas panel.

Peter Adams, Afternoon Foam and Surf; El Matador Beach, 2022, oil on panel.

Right: Karl Dempwolf, The Crags, Malibu, 2024, oil on canvas panel.

The mood is changing. They could be very powerful as you were saying, Rick. Being able to interpret the ocean that’s constantly moving, to make the painting effective and have a poetic response. There are so many moods you can get out of seascapes.

MO: Yes, literally a fluid landscape that just continues to move. In a good painting you can feel that movement.

EA: That’s the beauty of the Malibu area, because you have these amazing landscapes with the mountains, and the gorgeous trees, the ranch areas, and then you’ve got the ocean on the other side. It’s a pretty special part of the world, quite frankly. You could see why so many films were done there in the area.

AG: Speaking of cinema, I wanted to return to Anna T. Kelly’s painting of the Woolsey fire, because it’s such a phenomenal image, with so much drama compared to all of the other works in the show. Malibu is this incredibly beautiful, richly diverse place, but it’s also quite dangerous, with the constant threat of mudslides, landslides, and wildfires, and yet there are people who continue to build new homes here despite all of that. I wonder why more artists aren’t drawn to depicting ecological disasters given how much they are a feature of living in this place.

PA: It was hard for artists to get out there and paint during the fires. It was a very difficult thing to do because you weren’t allowed to go into the area. You’d really need to live in the area.

RG: I feel like this painting makes the point that I was trying to make—this is hardly sentimental. This is almost journalistic. Having served on the emergency operations committee at Pepperdine during the Woolsey fire, what a very frightening time that was. On our committee, we had some natural scientists, including Lee Kats, and he was reminding us that the forces of nature that carved this beautiful landscape are still at work. The water, the rain, the floods. What we love about the landscape was carved violently, created violently, and we should not be surprised that that’s still active. Someone like Steve Davis, one of our Pepperdine scientists who knows the Santa Monicas better than anybody, would go so far as to say nature is pushing back. It’s always reacting and adapting. I just think this painting had to be in the show when we talked about it.

I’m sure there’ll be people who will wince when they see it because it was painful for us. It was difficult, but I think it should make you feel that way. It should evoke a reaction.

THE FORCES OF NATURE THAT CARVED THIS BEAUTIFUL LANDSCAPE ARE STILL AT WORK .

MO: We had a brush fire across from my studio complex, probably 20 years ago, one day in the summer. One of the artists in the complex went out and did a plein air painting of the fire burning the hillside, the fire engines on the side of the road, and I was just blown away. I didn’t even consider painting a brush fire, but he went out and captured this day in the canyon. I always thought there was a negative connotation, like, “Oh, I’ve got to paint the destruction.” When I do see brush fires from a distance, like Malibu, for example, from Santa Monica, you have that huge, almost cumulus cloud of purple smoke. You can see some of those flames at the very bottom, and to me, there’s almost a beauty to that. That drama of the smoke and the colors that aren’t natural, but I’ve never considered painting them. Now you just lit my fire a little bit. Because I do see beauty in some of the smoke and just the drama of the dark in the middle of the day, and it is something to capture.

PA: There is that prejudice that if you paint a disaster scene, a car crash, or something where people have been hurt or killed, you’re trying to make money or sell your painting off of someone else’s disaster, out of someone else’s hurt. You never want to do that. There’s a reluctance to get involved with things that are somewhat disastrous, that are hurtful, where people have died or lost their homes and so forth. Yet it is part of nature, and it should be approached, but it has to be approached very respectfully.

RG: It raises questions about what our relationship with nature is. Even though there are big questions associated with that, and there were lots of people who lost their homes and it was a scary, scary time, there’s going to be more of it. There’s going to be a lot more of it.

MO: Maybe this painting in the show will open the minds of some of the artists to consider tapping into that in the future.

AG: Among the other rarities in this exhibition is a sculpture by Paige Bradley, who happens to be a Pepperdine graduate.

EA: The work by Bradley is like a sun worshiper out on the beach. That’s how I feel looking at this. It’s titled Illumination. You can just feel the sun capturing the body and warming up and uplifting the spirit.

RG: I saw it as surrender, and I mean that in a positive way. Being subject to all of this nature, it’s the opposite of controlling it. It’s a surrender to its beauty. To me, this work puts in the human perspective. The human spirit is now inserted into this story that we’re telling at the exhibition. Now, if you look at the Ray Roberts painting, what’s interesting is it’s almost a symbol of what we were just talking about. This is a resilient piece of stone here. Look at what has been washed away. I don’t know the geological story, but somehow it remains. It’s being carved away underneath, but there it still is, and it’s more beautiful than ever.

BEING SUBJECT TO ALL OF THIS NATURE, IT’S THE OPPOSITE OF CONTROLLING IT.

IT’S A SURRENDER TO ITS BEAUTY .

Paige Bradley, Illumination, 2019, bronze with electricity.

Ray Roberts, Matador Beach, 2023, oil on linen board.

Paige Bradley, Illumination, 2019, bronze with electricity.

Ray Roberts, Matador Beach, 2023, oil on linen board.