IT tip: If you are using this handbook electronically, the Navigation Pane/Document Map is helpful. On the View tab, tick the box next to Navigation Pane (or Document Map in older versions of Word) in the Show menu, and the contents list will appear on the left of your screen. You can then click on different sections to move around the document easily.

Every item in the contents is hyperlinked. Use Control (Ctrl) and click to go directly to that section.

Introduction

Welcome to the Action Research Modules TS2301 and TS4301 that are part of the Certificate in Education and PGCE.

As a partnership we have selected Action Research as a way for you to investigate your practice and continue to develop as innovative and critically reflective practitioners throughout your teaching career.

The Action Research module is designed to provide a safe space for you to learn and practise the research skills that will allow you to find and contribute your voice to the research in and around the teaching profession.

This handbook is designed to used alongside your action research classes.

What is Action Research?

Action Research is defined by a number of different people, but we are taking as our starting point the work of Jean McNiff who shared with us at a UCLan workshop in 2012, the ‘ purpose of action research is to improve practice, to generate theory that is grounded in the process of improving practice, and to test the validity of the claim that practice has been improved. You do this by referring to the evidence base which contains descriptions and explanations for the improvement.’

Action research is a process in which a specific focus of interest is identified and an interventiondesigned and tested with a view to gaining insight into the problem and ultimately solving it (Elliott, 2001).

Action Research promotes transformative change through the simultaneous process of taking action and researching the impact of the action and what it is you have learnt from your enquiry - underpinned by critical reflection.

Action Research helps us to understand what is happening in our classrooms and identify and investigate changes we could make to improve teaching and learning, such as the effectiveness of specific instructional strategies for our specialist subject, the performance of specific students, and classroom management techniques.

Educational research that uses control groups and experiments can sometimes feel disconnected from the realities our classrooms, and feels contradictory to supporting students, but Action Research is truly connected to ourpractice with ourlearners

According to Hensen (1996), action research:

• Helps teachers develop new knowledge directly related to their classrooms.

• Promotes reflective teaching and thinking.

• Expands teachers’ pedagogical repertoire.

• Puts teachers in charge of their craft.

• Reinforces the link between practice and student achievement.

• Fosters an openness toward new ideas and learning new things.

• Gives teachers ownership of effective practices.

By this second stage in your teacher education and teaching practice you are probably already doing some form of action research already. Every time you change a lesson plan or try a new approach with your students, you are engaged in analysing out what works by interpreting what is happening in your classroom and what your leaners are telling you. Even though you may not acknowledge it as formal research, you are still investigating, implementing, reflecting, and refining your approach.

Over the years many trainee teachers have engaged in Action Research and have really enjoyed the process while learning a great deal about their own practice, their learners and teaching and learning strategies.

We hope that you also enjoy taking part in this type of investigation and go on to use the principles of it throughout your teaching career, perhaps sharing your research with colleagues or even publishing your work.

Thinking about publication, the UCLan Teacher Education Partnership, produces an annual publication of past trainee teachers’ action research reports, ‘Throughthelookingglass: ReflectiveResearchinPostCompulsoryEducation’ .

The journals are available in college from your programme leaders and are also in the college library. They are very useful in getting ideas for investigations and also building on research activity that has taken place earlier.

As a UCLan trainee teacher, you have the exciting opportunity to contribute to the next edition of our journal. Your tutor will explain how you can contribute.

There are many good texts written about action research and you will find them in the online reading list via these links:

CertEd

https://uclan.alma.exlibrisgroup.com/leganto/public/44UOCL_INST/lists/437753884000382

1?auth=SAML

PGCE

https://uclan.alma.exlibrisgroup.com/leganto/public/44UOCL_INST/lists/437756422000382

1?auth=SAML

A good starting point is Jean McNiff’s work which you can access via her website www.jeanmcniff.com where you will find lots of free material and a booklet that I am sure you will find valuable.

Next, please look at the exercises (in the Activities section of this handbook) and start to draft out your ideas for your Action Research intervention.

Exercise One: Identifying the focus of your research intervention

Exercise Two: Challenges and Solutions

Exercise Three: Research intervention - `Problematising' an area of study

Exercise Four: Progressive focusing of the research

Section One: Developing a small-scale action research project Introduction

This module is concerned with the implementation of a piece of small-scale action research into any aspect of your practice that you would like to develop or explore. For a description of action research, we take as a starting point Jean McNiff and Jack Whitehead’s view that action research is a step on from ‘just’ teaching, in that ‘action research insists on teachers justifying their claims to knowledge by the production of authenticated and validated evidence, and then making their claims public in order to subject them to critical evaluation’ (McNiff and Whitehead, 2005, p.2)

Due to the focus on one of the groups you teach and the short time frame of the module, your research is necessarily ‘small-scale’, but that does not, in any way, diminish the value of your research focused on an aspect of your professional practice. Whilst your research may be small in scale, it can be big on impact.

Action research is about taking action and doing research. Theorised by Kurt Lewin and later elaborated and expanded on by other behavioural scientists, action research is both a research ‘approach’ anda research ‘process’.

Action research (and for that matter all kinds of research) is more than just doing activities. Remember the term ‘action research’ contains two words:

Action: The ‘action’ of action research refers to what you do: It involves you thinking about the circumstances you are in, how you got there and why the situation is as it is, i.e., your social, political and historical contexts.

Research: The ‘research’ of action research refers to how you find out about what you do: Data gathering, reflection on the action shown through the data, generating evidence from the data and making claims to knowledge based on conclusions drawn from authenticated evidence (McNiff, 2013, p.25).

The aim of the action research module is to build on your understanding of professional practice and support you in designing, creating, and undertaking your own action research project exploring your subject specialist teaching.

To support you in this, you will undertake your research project using this four-stage process:

• The first stage is to create your research proposal and ethics statement. You will do this by reflecting on your teaching practice and decide on an aspect (or topic) of your personal practice that you would like to explore – something that poses a difficulty or something you think could be improved: This will be the focus of your research intervention

You will focus your intentions into a conceptual framework of your key ideas, aim and research questions and your data collection methods.

Next, you will create your theoretical framework by reading around your chosen aspect to find out what literature, research or theories there are already in your topic area that you can build on and to devise an intervention that could lead to improvements.

• The second stage involves the formal process of submitting the research proposal and ethics. You will write your ideas and the outline of your intervention, including any ethical considerations which will need to be made, and submit a proposal and ethics form. Your tutor will need to approve your ideas before you start your project.

• The third stage is the period of time, usually four to six weeks, where you undertake the intervention and collect your data. We suggest you undertake a teaching observation during your research intervention, as this will allow your tutor to provide feedback and guidance on your intervention as it is happening

• The fourth and final stage is your Action Research report. Taking on board feedback on your proposal, you will write your research report. This handbook provides detailed information on each step in the research process, and you will cover this in more detail in class with your tutor and peers. There is a detailed assignment brief and framework for you to follow and you will be drafting the sections of your report each week.

The examination of – or research into – your practice is referred to as an ‘intervention’. All interventions are based around improving our practice for the benefit of ourselves, colleagues, and learners.

Your action research will take you on a reflective journey, one where you will follow a reflective cycle to develop your practice. McNiff says we should always be asking ourselves, ‘How do I improve what I am doing?’ and she suggests a useful plan for your research below:

• We review our current practice.

• Identify an aspect we wish to investigate.

• Ask focused questions about how we can investigate it.

• Read around the area – what has been done before, what research and theories are there (this is what is known as a literature search).

• Choose/decide on a way forward.

• Try it out and take stock of what happens.

• Modify the plan in light of what we have found and continue with the action.

• Evaluate the modified action.

• Reconsider what we are doing in light of the evaluation.

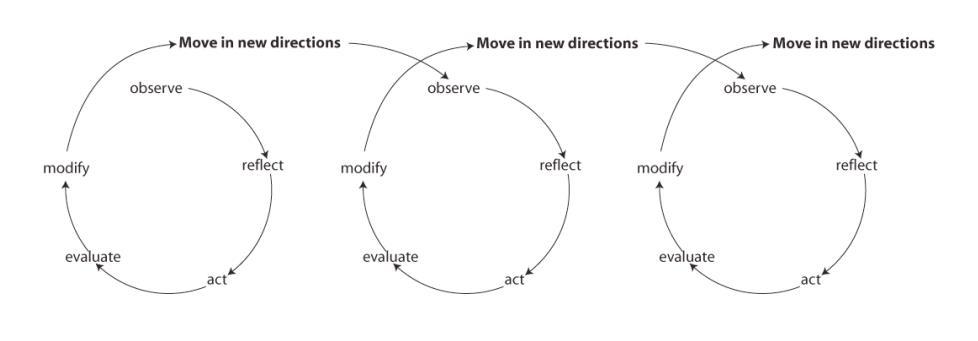

And so, Action research is widely acknowledged as a reflective cycle, seen here in the diagram from McNiff & Whitehead (2006):

But as teachers and researchers, action research is a continuous process, where one cycle of reflection and action leads to another, and another as we see in this extended diagram:

When you plan your action research you think about something you want to investigate, a real live issue that relates to the teaching of your specialist subject and needs your attention. It does not need to be a problem, though it tends to be something problematic or that poses a difficulty, or something interesting you are curious about, such as:

• Whether you are supporting your students to understand a threshold concept

• Re-organising your classroom in a more inclusive way.

• Adapting your teaching to ensure learners are making good progress.

Hints

Do chose an intervention that is subject related as opposed to generic.

Do choose an area to investigate that you can manage in the time available.

Do try to build on what other people have done - find this out from your reading.

Don’t choose something where it would take too long to see an impact. Don’t choose an intervention that is too insignificant, too ‘everyday’ or something that you could change and evaluate in only one lesson.

Some writers in the literature, however, do say that an enquiry begins with a problem. Whitehead (1989), for example, proposes that you begin your enquiry by identifying a situation where your values are denied in your practice: you may believe in social democracy, but you do not always give people an opportunity to state their point of view. This is a valuable idea that has been used widely.

* To note: in earlier texts I have used the language of ‘What is my concern?’ However, I now appreciate that the terminology can be misleading. This was brought home to me strongly in July 2012, when I attended a meeting at the University of Central Lancashire, and colleagues there explained how easy it was to turn the word ‘concern’ into ‘problem’. ‘My practice is fine,’ said a lecturer, ‘although I appreciate that I need to produce evidence to show how this is so.’ I have therefore abandoned the word ‘concern’. I have in any case always understood it as implying ‘something to be investigated’ but am now concerned that ‘concern’ may be too readily seen as ‘problem’. I do not see life as a problem, but as something to be engaged in and enjoyed.

Jean McNiff’s closing statement above is helpful. Life and teaching are not ‘problems’ but challenges that we engage in through the process of asking questions and being creative about solutions to our changing situations. We can enjoy meeting those challenges and improving our teaching and learning as a result.

Other writers and researchers view action research from different perspectives. None are right or wrong just different in their focus. Cohen and Manion (1994) define action research as a ‘small-scale intervention in the functioning of the real world and a close examination of the effects of such an intervention’ (1994, p.186) so there are some similarities here to McNiff’s earlier description.

We can use Cohen & Manion's (1994) perspective to clarify further the context of the intervention: 'action research is situational - it is concerned with diagnosing a problem in a specific context and attempting to solve it in that context '. Here Cohen and Manion are concerned with diagnosing a problem and solving it, a linear and more prescriptive approach, while McNiff is using language around investigations and exploring practice with the intent to improve what is going on. This is more unpredictable and ‘messy’, and the outcomes of the investigation are not always what you thought they would be.

Both of the above approaches will result in us learning something about ourselves as practitioners, our learners and also the teaching and learning process. The insight gained through your study will hopefully have value to you and your organisation. Although it may not be completely transferable into another classroom / situation what you have learnt is still important to other practitioners.

Cohen & Manion (ibid)go on to discuss the difference between appliedresearch(where

there is an imperative to produce generalisable knowledge by controlling the sample and reducing the number of variables) and actionresearch(which is concerned with illuminating a specific situation). McNiff states that the purpose of action research is to improve practice, to generate theory that is grounded in the process of improving practice, and to test the validity of the claim that practice has been improved. You do this by referring to the evidence base you collect which contains descriptions and explanations for the improvement.

Supporting documents

Your tutor will give the supporting documents to you at the start of the module.

Research Proposal and Ethics

A template has been designed for you to submit the proposal and ethics for your research to your module tutor beforeyou start your research. You may discuss this in a tutorial with your tutor.

Participant information and consent

Before you start your research and data collection you must gain informed consent from your participants (your leaners).

There is a template in the appendices of this handbook for you to use.

Action research assignment brief and writing framework

A writing frame for the research project report itself is provided in the assignment brief for the report. This will guide you in structuring your final report.

Section Two: Theoretical frameworks

As we read in the introduction to this handbook, ‘the purpose of action research is to improve practice, to generate theory that is grounded in the process of improving practice, and to test the validity of the claim that practice has been improved. You do this by referring to the evidence base which contains descriptions and explanations for the improvement.’ (McNiff, 2012).

Therefore, as researchers we must look to theory and literature around the focus of our research project andaround the intervention we are planning to undertake and research with our learners. To evidence critical thinking, you must look at more than single sources of evidence and you must refer to current, relevant literature.

REMEMBER Teacher Education has an intellectual basis. Please do not rely on internet searches for information. Use resources from your college library and remember that you have access to the multi-million-pound resources in the UCLan Library.

Consider carefully whether searching the internet (e.g. with Google) is appropriate to your search. If you do use this method – in addition to a library search - it is even more important to focus the search and to be very aware of which sources are reliable and which may not be.

Remember this is not a PhD and you are not required to carry out a search to identify every single piece of existent research relevant to your own intervention.

What we do require of you is that you demonstrate knowledge of the literature and research that relates to your teaching situation and intervention, and that you can summarise some of the main findings in key research that underpins your own project.

Literature search

A literature search involves finding out what articles, books, government reports, policy developments and so on have been written around subjects, themes, analyses, etc which have relevance to your research into your subject specialist teaching practice. This includes finding out about:

• The background and context of your research theme, e.g. policy, recent developments.

• What sort of interventions have been tried and researched before – so that there is a good rationale for the one you choose, and you can potentially build on others’ research.

• What theory and research are there surrounding the area you plan to investigate (e.g. learning theory, research into specific teaching and learning techniques).

These sources may be available in paper or electronic versions and obviously a library is the best place to start. Asecondarysource,but a good starting point, will be the bibliographies, abstracts, and indices, as these will provide a trail to the primarysourcereferences which will provide the important data you are looking for. Your quest for both paper and electronic sources will be more effective if you develop a systematic search method. Identify your subject, list the keywordsand then set some limits to narrow down the search, for example, time period,scope,formofmaterial,educationalsector,etc.

Exercise five (in the Activities section of this handbook) will help you create your theoretical framework.

Section Three: Research Methodology

Carrying out your intervention would be classified as ‘just’ teaching, but by investigating and evaluating the success of the intervention in a systematic way, and creating new knowledge from that process, you make it into research.

Action research has the capacity to empower teachers by developing critical reflection on their practice, and professional growth. In particular, ‘teachers are empowered when they can implement practices that best meet the needs of their students and complement their particular teaching philosophy and instructional style’ (Johnson, 2013, p.153).

‘Whereveryouwanttogoyouhavenochoicebuttostartfromwhereyouare.’ (Karl Popper, 1902-1994)

Action research’s strength lies in its focus on generating solutions to the practical problems we encounter everyday ion our practice (Meyer, 2000). But action research is not simply about solving ‘problems’ it’s about seeing how things could be improved, how things can be made better for everyone.

By engaging with research and literature, and the subsequent development or implementation activities, we harness the ability to enhance our learners’ experiences and empower ourselvesas teachers.

There are variety of types of action research, individual action research, collaborative, action research, system-wide action research, participatory action research, etc.

For this module you are undertaking the first example, individual action research where:

- You as the researcher decide upon the research question and research design.

- You as researcher, conduct the research

- The focus is to improve practice, to ‘find a better way’.

- Your learners are the participants.

- You try new ways of working – through the introduction of an ‘intervention’.

- You observe the intervention in action and collect qualitative data from your participants.

- You thematically analyse this data to show themes.

- You interpret the themes to make sense of things and answer your research question. (Individual action research is situated in the interpretivist paradigm.)

Research language can be complex but as you progress through the stages of research, several key terms will become familiar to you.

Here are two examples – the first an 'interpretivist'approach, involving a researcher formulating research questions and aims. The interpretivistwill be following an inductive process where the theory is drawn out of and informed by the practitioner's experience-based knowledge of the context (i.e. the teaching situation).

The second is a positiviststance, which establishes a theory prior to the investigation. In this

approach we are saying this is the theory I want to work with, and I am going to prove or disprove the theory by testing it out in some way or another.

For this module you will be engaging with the first, interpretivist, approach when you are undertaking your action research. You will be collecting data and interpreting meaning from it.

The research must be empiricallybasedand exploratory(using primary data that you collect from and with your participants) rather than deskorlibrarybased.

In other words, the action research focus encourages practitioners to build on their unique knowledgeof a particular learning context It is concerned with doing things more effectively in future, rather than analysing the characteristics of a past event. It allows you to explore your practice, investigate what going on there, and draw new insight as a result. You are involved in contributing to knowledge in the teaching of your subject. You will collect lots of data during the research process, but you need to turn that data into evidence to illustrate to other practitioners that your new insights are not just your opinion but are based on solid evidence that can be related to other established theory

Action Research Cycle

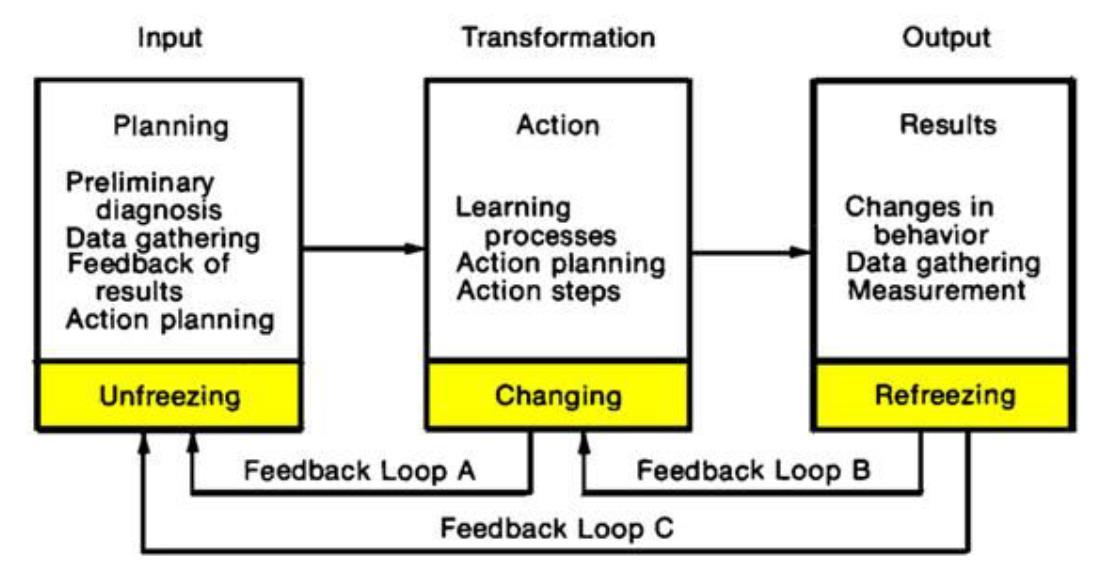

In section one, we saw McNiff & Whitehead’s (2006) models of the action research cycle. Kurt Lewin’s action research model shares a process of change that involves three steps:

• Unfreezing: Faced with a dilemma or disconfirmation, the individual or group becomes aware of a need to change.

• Changing: The situation is diagnosed, and new models of behaviour are explored and tested.

• Refreezing: Application of new behaviour is evaluated, and if reinforcing, adopted

To look at Lewin’s approach in more detail, we can follow his reflective cycle:

At this stage, in the cycle, things will have changed, including your own knowledge of the situation. The new data collection period is based on this change, thus it is really a spiral rather than a cycle

7 Reflecting on developments starting to explore again

1 Gathering information –looking at your practice

6 Reflecting on, and analysing the information to find evidence

Practitioner Research

The Action Research Cycle

BasedontheLewinmodel ofExperientialLearning.

(Becoming a ‘knower’)

Using a number of methods that are appropriate for the information to be found out. More than one source of information allows you to triangulate the data and get a balanced picture about what is happening.

Using for the information to be found out. More than one source of information allows you to triangulate the data and get a balanced picture about what is happening.

5 Gathering information (data)

4 Implementing possible solutions, trying out ideas

2 Diagnosing or identifying the focus of your concern

3 Formulating a number of research questions

Formulating Research Questions

As we have seen, action research does not begin with a hypothesis or a presumed outcome (as is the case in a quantitative study). However, Action Research cannot begin without a plan and a key part of that plan is a research aim and a set of clear research questions.

Well-crafted questions that can give shape and direction to a research project is a reflective and interrogative process, one that is often underestimated.

In section one we looked at developing a small-scale action research project and designing an intervention. A key part of the intervention are the research aim, and the research questions you wish to answer so that you can develop your practice. In exercise four (in the activities section of this handbook) you will have clarified the aim of your project and started to think about the specific research questions you intend to answer.

The research aim is a good place to start: What are the questions you will need to answer to fulfil your aim? These might be quite broad questions.

Qualitative inquiries like Action Research involve asking the kinds of questions that focus on the whyand howof human behaviours and interactions. Thinking back to Lewin’s model of action research then (on the previous page) where we are becominga‘knower’our research questions need to articulate what we want to knowabout our learners, our practice and what is happening in our classrooms.

Use good qualitative wording for these questions.

▪ Begin with words such as “how” or “what”

▪ Include what you are attempting to “discover,” “generate,” “explore,” “identify,” or “describe”.

▪ Ask “what happened over time?” to explore the process.

Writing clear research questions takes practise and time: But this is time well spent, as you will revisit these questions and answer them in your research report.

Exercise six (in the activities section of this handbook) is designed to help you craft your research questions

Rigour of Qualitative Research

As you will have noticed, one of the assessment criteria for Module TS2/4301 is your analysis of the research methods you have used during the study, and this would also include the effectiveness of your intervention. Central considerations when evaluating any research method are establishing the validity and reliability of the chosen approach.

In quantitative research reliability refers to research whereby, if it were to be carried out on a similar group of respondents in a similar context, it would produce similar results. However, in qualitative terms, reliability refers to if the tools we are using to collect data are ‘fit for the purpose’. In other words, if they provide consistency in our data collection (the tools we

use allow us to produce the same data whenever we use that tool), and also if there is a fit between what researchers record as data and what actually occurs in the setting that is being researched. Cohen, Manion and Morrison explain it as:

‘… a fit between what researchers record as data and what actually occurs in the natural setting that is being researched, i.e. a degree of accuracy and comprehensiveness of coverage…’ (2000, p.119)

Validity

Denscombe notes that in qualitative research, validity relates to truth. More specifically in AR this relates to construct validity – the findings reflect the way the participants actually experience and construe situations in the research – that the findings are told though the participants’ eyes.

• The data and the methods are right. In terms of research data, the notion of validity hinges around whether or not the data reflects the truth, reflects reality, and covers the crucial matters (Denscombe 2003:301).

• In qualitative data, validity might be addressed through the honesty, depth, richness and scope of the data achieved, the participants approached, the extent of triangulation and the lack of bias or objectivity of the researcher (Cohen et al. 2000:105).

• Similar to validity, is the concept of credibility in that the purpose of qualitative research is to describe or understand the phenomena of interest from the participant's eyes (Trochim, 2006).

Validity is the ability of the method to measure what it was intended to measure. In terms of action research Cohen and Manion make an exception which they define as essentially different in nature to ‘scientific’ applied research in that it is specific to a particular context and is concerned with addressing particular problems, rather than controlling variables in order to be able to generalise the findings to other comparable situations.

According to Creswell & Poth (2016) validity in qualitative research is concerned with trying to assess the “accuracy” of the results, as best described by the researcher and the participants. They believe that validity is used to emphasize a process of detailed description, and a close relationship between the researcher and the participants.

Generally speaking, then, as with the principles of assessment, in research terms validity, refers to accuracy of measurement and reliability to the consistency of measurement. However, validity and reliability in qualitative research differs to quantitative research. Lincoln and Guba (1985) used “trustworthiness” of a study as a qualitative equivalent for validity and reliability. Trustworthiness is achieved by credibility, authenticity, transferability, dependability, and confirmability in qualitative research.

To see these terms in action research, Whittemore, Chase, and Mandle (2001) give us some good descriptions:

Credibility

We must undertake a review of literature around the focus of the research and use triangulation

of data sources and ensure the results of our enquiry offer an accurate interpretation of the participants’ meaning.

Authenticity

Which may be framed in terms of being attentive, intelligent, reasonable, and responsible in engaging with the challenges of action research (Coghlan & Brannick, 2014). Are different voices heard in the research? As action researchers, we have to acknowledge all the data we collect, we cannot ignore (or bracket) findings we do not like, understand or think are irrelevant. All participants’ voices must be included.

To confirm that the results are transferable between the researcher and those being studied, we must give rich, thick description in our discussion of findings.

As researchers, we acknowledge dependability by understanding that the outcomes of our small-scale research will be subject to change and instability rather than looking for reliability.

Confirmability

Relates to the degree to which the findings of the research study could be confirmed by other researchers. Confirmability is concerned with establishing that data and interpretations of the findings are not figments of the researcher’s imagination but are clearly derived from the data.

Two other elements of rigour we should consider are:

Criticality

Is there a critical appraisal of all aspects of the research? Remember, we make things critical by using research and literature.

Integrity

Is the researcher self-critical? Are you reflecting on your research, its design, your role, and impact within in it, and what the outcomes mean for your practice?

Section Four: Research Methods

Qualitative research acknowledges the complexity of the classroom learning environment. While quantitative research can help us see that improvements or declines have occurred, it does not help us identify the causes of those improvements or declines, nor does it allow us as practitioners to interpret meaning from our learners and our practice. Action research using qualitative data (or mixed method) allows us to connect with our learners’ performance, behaviours and opinion, so that we can use to adjust our curriculum content, delivery, and instructional practices to improve student learning and progress. Action research helps is implement informed change!

The collection of data may have some quantitativeelements, such as the collection of contextual statistics about what,where,when,andhow?However, the purpose of such numerical data is to set the scene. There should be substantially more concern to gain insights into answers to the question ‘why?’ It is important to not only understand what is happening but also the reasons for the particular phenomena and to achieve this you will focus on qualitative methods.

Data collection methods

Data collection methods are inextricably linked to the methodology – a qualitative research project must use qualitative data collection methods.

When deciding on your data collection methods, you must also consider your research questions and think carefully about the data you need to answer the questions.

Let us now examine six examples of commonly used data collection methods

1 Observation

The careful observation of particular groups or individuals occupied in an activity relevant to the research focus will provide a tremendous amount of data. However, as Nisbet warns us ... observation is not a natural gift but a highly skilled activity for which an extensive background knowledge and understanding is required and also a capacity for original thinking and the ability to spot significant events. It is certainly not an easy option…(Nisbet, 1977 cited in Bell, 1999, p. 156)

Observations provide a first-hand, primary source for data. Researchers can see for themselves what is happening rather than relying on the perceptions of others as recorded during interviews or through the use of questionnaires. However, because in most `live' situations many things are happening simultaneously, a researcher must be organised in order to identify the important events and record data related to them. As Bell goes on to say:

This is harder than might at first appear... You need to be clear whether you are interested in the content or process of a lesson or meeting in interaction between individuals, in the nature of contributions by teacher, pupil or

committee members, or in some specific aspect such as the effectiveness of questioning techniques. (Bell, 1999, p.159)

All observers enter a situation with particular attitudes, needs, prejudices and biases, which affect what they see. Be aware of the ‘halo' effect where, for example, well-dressed, respectful students can create positive feelings in observers, which are not so evident when they are confronted by untidy, noisy students. These basic differences in perception can affect the interpretation of behaviours with the former group's ‘lapses' being tolerated where they would be noted in the latter group's case

In addition, it should be remembered that the presence of an observer may well alter a situation from the norm. The teacher or the students may act differently from the way in which they usually behave. This has been called the `Hawthorne effect; - the tendency, particularly in social research, for people to modify their behaviour because they know they are being studied, and so to distort (usually unwittingly) the research findings.

Observations will, by their very nature, be a ‘snapshot' of a particular situation and the observer will not be fully aware of what has gone on before the visit and or will occur afterwards. These unobserved sessions will inevitably be influencing what has been seen but the observer cannot be sure about the extent of these influences.

Researchers need to decide whether they will try to be an unobtrusive, 'fly-on-the-wall' type of observer, or will they take on the role of a 'participant-observer' who becomes an accepted part of the group during the research. IT is more likely that you be take the role of 'participant-observer', as you are a part of the class with your learners.

It is also important to be aware that, despite using a well-considered, systematic approach, an observer can only look in one direction at once (as can a camera) and so the data collected will inevitably be partial.

Finally, despite the very best of intentions, absolute objectivity is impossible due to the many ‘confounding' variables at play within a classroom. However, this does not negate the value of small-scale, action research projects. Remember, you are trying to illuminate a particular situation in order to move towards a more informed position and, providing that you are aware of (and articulate within your report) the limitations of what you are undertaking, the insights you gain will outweigh the counter-effects of subjectivity.

2 Questionnaires

During recent years, questionnaires (in one form or another) have been so heavily used within all branches of research and evaluation that many people believe that their design is simply a matter of gathering together and listing a set of appropriate questions. However, this is not true! Bell argues that ‘it is harder to produce a really good questionnaire than might be imagined…’ (1999, p.118)

One of the problems is that the use of questionnaires does have its roots in positivist research methodology (see Section One) as they were originally designed to collect factual data in order to provide quantified and generalisable outcomes. As mentioned earlier, it is more difficult to use questionnaires to provide insights into questions about why particular events have occurred.

However, qualitative data can be gathered through questionnaires if they are carefully designed for that purpose. So, it is important that you:

1. Introduce the questions clearly and honestly with a statement or explanation about its purpose. You may need a statement about confidentiality.

2. Keep the questions simple, short, self-explanatory and as non-threatening as possible.

3. Be aware of the focus of your research, i.e. start with a broad perspective but become more specific, leading the respondent towards the key issues.

4. Do not over-complicate the questions by asking more than one thing or by including too many qualifying statements.

5. Closed questions allow numerical analysis but may well be too restrictive for a qualitative study. Pose questions that require an open answer qualitative.

6. Ask ‘what’ and why’ and ‘how’ questions, to ensure your participants are able to tell you their experience, not just make a ‘best fit’ with options that you give them.

7. Avoid imprecise terminology, which can be interpreted in different ways by different respondents. Very,quite,completely,extremely,sometimes, are examples of these.

8. Avoid leading questions such as ‘Doyoufeelthatthereissufficientconsultationwhen collegeplansarebeingdrawnup?’Instead ask, ‘Whatwouldhelpyou todealwithnew collegeinitiatives?’

9. Minimise the possibility of misinterpretation or putting words into respondents’ mouths. For example: Wouldstaffdevelopmenthelpyoutodealwithnewcollegeinitiatives?

10. Be sure to test your questionnaire with peers and colleagues first, to see the sort of data your questionnaire will generate – and how useful this will be in answering your research question.

Try to be aware of the relative value of questionnaires to you as the researcher:

Strengths

• A lot of information can be obtained quickly

• Costs are low compared with other methods.

• They can provide comparable information

• They provide the opportunity for follow-up work.

• They are good at establishing facts such as ‘what’, ‘when’ & ‘how’

Weaknesses

• Only a snapshot in time

• Can lead to respondent exaggeration.

• There are problems with respondent interpretation

• If poorly designed, they can invade privacy.

• Poor at measuring sensitive issues or showing the ‘why’ or ‘how’ of something .

If you are attempting to understand attitudes or feelings, you can use a range of common-sense categories, which have been well tested. In some circumstances, you may wish to add ‘don't know’ but the ambiguity of phrases like ‘other’ should be avoided:

(excellent - good - fair – poor), (favour – oppose), (good idea - bad idea)

(too many - not enough - about right) (better - worse - about the same), (regularly – often - seldom – never), (approve – disapprove), (for – against), (agree – disagree), (too much - too little - about right), (vary - fairly - not at all), (more likely - less likely - no difference)

Remember…

Appearance - A crisp professional look will encourage a good response. Sophisticated IT now means there is no excuse to produce a poor-looking, unprofessional questionnaire.

Excellent printing facilities mean that multiple copies may be produced without loss of impact, and there are many ways to create an online questionnaire, e.g. with Google Forms, Survey Monkey, Menitmeter or Microsoft Forms.

Again, test the layout with peers and colleagues and always ensure that the final result is perfect for going into the public domain

Explanation - Use the participant information and consent form, to explain the purpose of the questionnaire.

Return date – Make sure that the respondent knows the deadline and how to return the questionnaire.

Repeats - Be prepared to supply replacement questionnaires and even reminders to late returners

Thanks - A note thanking the respondents at the end of the questionnaire will be appreciated and may encourage the return of the questionnaire.

Before using your questionnaire, test it on your class peers to see if it will give you the data you need/ think it will.

3 Interviews

A familiar and effective way of gaining information is to go and talk to the person involved with the topic you are researching. Using interviews in research has the same attractive simplicity in that, assuming the source of information is willing, you could gain direct access to valuable data. However, even a simple interview could well involve you in a number of methodological problems:

• Interview bias - because of the interactional nature of interviews and despite your best intentions, it is very easy to influence the interviewee during the process. This may simply be your tone of voice, non-verbal communication through posture or gesture or the power position of the interviewer.

• Lack of control - once an interview is under way, it is extremely difficult to remain in control of the flow of information.

• Misinterpretation - in a situation where participants are attempting to articulate difficult concepts within a restricted time frame.

On the other hand, an interview has many advantages which other methods do not:

• Depth of information - during a carefully and sympathetically handled face to face encounter an interviewer can get at sources of information (often involving extremely subtle nuances) which other methods could not achieve. These often provide `leads' which can be followed up by other methods.

• Confirmation of other data - interviews are excellent at part of a triangulation process used to ensure the validity of the data collection process by confirming the indications gained from other methods.

• Flexible - during an interview it is possible for a researcher to probe a range of issues and follow up the promising ones in a very flexible way, which other methods cannot match.

Planning

Before conducting an interview, it is important to consider a range of factors which may well affect the outcomes of the research - intendeddataanalysis,stanceoftheresearcherandformofthe interview. Before you start, you should be aware that interviews often generate a huge amount of data which has to be processed. If you record the interview, you can reckon on it taking you six times the length of the recording to transcribe the material it contains. This workload can be reduced with more careful planning in terms of the length and form of the interview and the careful indexing of the recorded material in both written and audio form.

Stance of the researcher

As suggested above, the interviewer has the responsibility for setting the parameters of the encounter and will, inevitably, set the tone of the discussion. It is worthwhile considering beforehand what researcher `stance' would be most beneficial in terms of the data you intend to collect. You may decide to use arespondentapproach where the interviewer remains in control. Depending upon the situation, this may take many forms from a sympathetic, friendly relationship to a more direct, almost aggressive search for the required information. An alternative is an informantapproach, which is an unstructured discussion allowing issues to be uncovered and then investigated.

Form of the interview

The style of interviews varies enormously. A researcher may wish to use a highly structured approach, where each interview is carried out using a consistent methodology. The same questions will be asked in the same order and recorder using the same process each time. Despite what has been said previously about interview bias, this method does allow the researcher to move towards a more reliable process and the interview data collected can be compared more systematically with other interviews and other data collected using other methods

A semi-structured approach would use a consistent pattern of questioning initially, but would then follow this up with more probing, individualistic questioning. An unstructured interview is often difficult to manage, particularly in terms of length. However, it does allow the researcher freedom and flexibility.

Before interviewing your participants, test the questions on your class peers to see if they will give you the data you need/ think they will.

4 Focus groups

Focus groups can be a helpful way of collecting qualitative data. In your group you can ask your participants about their perceptions, opinions, beliefs, and attitudes towards your action research intervention

Focus groups are usually 6-10 people, typically last about 30 to 90 minutes. A focus group lasting more than 90 minutes probably includes too many questions or topics for discussion.

A focus group can be led by the researcher, or a third party, or you can leave the group with the questions and ask them to record their discussion (you will need consent for recording).

It’s important that the focus group is organised so that it is appropriate for the type of participants in the group. Make sure:

- The participants understand how the group will work.

- Participants understand how their responses will be used.

- What the purpose of the group is: Why are they doing this?

- The questions are clear and specific (see the advice on writing questionnaire questions, above).

- All participants participate.

- That you are aware of the participants body language and engagement and check that they are happy to proceed.

One negative of focus groups can be the ‘Group effect’ or ‘group bias’ which can have a major impact on the results of your focus group. This ‘effect’ can lead to participants exaggerating responses and so your results may not accurately reflect the true opinions of all participants.

It’s important to monitor the group so that they are able to respond truthfully – but also keep on track.

Before conducting the focus group with your participants, test the questions on your class peers to see if they will give you the data you need/ think they will.

5 Artefacts (and documents)

As well as questionnaires, interviews and focus groups, you can also use artefacts or documents as a good source of qualitative data. Common types of artefacts are written texts such as documents, diaries, journals, memos, meeting minutes, and letters. For example, if your intervention is to improve students written work, you can use copies of their work which show improvements as data. Or if your students are keeping a reflective journal or action plan, these can be good sources of qualitative data.

6 Journal and Fieldnotes

You are required to keep a research journal throughout this module that will show all of your thinking and reflection on your action research. Essentially your journal is all the ‘workings out’, plans, and prototypes of your research and questions (the ‘messy’ stuff that you will tidy up to create your finished research report).

You will also use your journal to record ‘fieldnotes.’ Fieldnotes are qualitative notes recorded by researchers in the course of research, during or after their observation of a specific event or phenomenon they are studying – for you this is your students participating with your intervention.

The notes may be read as evidence that gives meaning and aids in the understanding of the phenomenon.

Finally…

Remain open to the reality that data is all around you. You have access to students’ work, assessment records, evaluation sheets, informal discussions, reflective diaries and student logs, past records, etc that may help in your understanding of changes in current data. Everything we have is data of one sort or another and you may be able to use this in your research discussion.

Section Five: Ethical practice

The first rule of ethical practice is that researchers must do no harm. The philosophy of Action Research is to change things of the better and in doing so,

All researchers create some type of data as part of their research, from our observations, questionnaires, interviews, focus groups, etc and a systematic and rigorous approach to research data management is fundamental to good research practice. Therefore, all data generated during your action research should be appropriately managed. It is inevitable that you will be faced with ethical challenges during the design and implementation of any research. The problem of the confidentiality of responses usually causes the greatest concern, but also issues related to race and social background need to be born in mind when planning question formats. Most researchers will usually be in a position where they will have to continue working with colleagues and living with the consequences of their research long after the project is finished.

To support your design of an ethical research project, you will complete the ethics and data protection sections of the research proposal

Data Protection Checklist

Your Action Research project is likely to include the collection of personal data. (Personal data is data relating to a living individual who can be identified from those data (or from those data and other information in our possession or likely to come into our possession). This checklist will ensure that you have properly considered how you are processing (using) the personal data you are collecting. You should provide further details where these are requested so that your proposal can be approved.

Participant Consent

The informed consent process requires that prospective participants, and/or their legal guardians/advocates, are provided with sufficient information about a research project to make a knowledgeable decision about whether or not they want to take part.

The design of an information sheet must reflect the nature of the research study and be accessible to the intended participants. For example, an information sheet for a complex study, or one that carries potential risks (such as a clinical trial), will need to be relatively detailed; an information sheet for children may use graphics or photographs rather than just text.

There is a participant information and consent form in the appendices of this handbook for you to customise and use for your research project. You must add a copy of this to the appenidces of your final report when you submit it.

For literate adults, information is normally provided in the form of an information sheet that they can take time to read and consider. However, there are many circumstances in which the procedures for informed consent will need to be customised, for example, when researchers work with children, people who have learning disabilities, cognitive impairments, have low levels

of literacy or don’t speak English fluently1. Given the requirement for fairness, if no special provision is being made for these participants, then they are effectively being excluded from the study, and this must be stated in the protocol and/or research proposal and justification must be given.

When working with children or vulnerable adults, you may need to produce two versions of the information sheet; one which is accessible to the participants and one which is intended for the legal guardian (e.g. parent / guardian/ caregiver etc.). The two versions must be aligned in terms of content and provide enough information, in appropriate detail, so that consent is fully informed.

It is important to remember that informed consent is an ongoing process, not just something that occurs at the start of a study. Consequently, participants must be free to withdraw their participation at any time and details of how they can do this should be clear on the information sheet. Make it clear that participants do not need to offer any reasons or explanation for why they wish to withdraw from the study.

It is important to ensure that participants are able to ask further questions and are provided with details about where they can find further appropriate information on the specific research area. This applies throughout the research process, even after the information sheet has been read and consent has been obtained.

Working with children

In the UK, people under the age of 18 (16 in Scotland) are classified as children. However, researchers should not assume that all children are vulnerable and incapable of providing consent because of their age. Children under the age of 16 can be capable of weighing up the pros and cons and making decisions for themselves. For studies involving children under 16, researchers may invoke the notion of “Gillick competence” which recognises a child’s capacity to make informed decisions for themselves. Whilst it has been legally validated for decision-making in healthcare, the basis for applying Gillick competence in research has not been tested legally. Researchers need to be aware that there is debate about how to assess Gillick competence, and whether consent should be sought from the child and assent from the parent or vice versa. Hence, while it is good practice to seek consent (or assent) from a child, it is normally in their best interests to also seek consent (or assent) from their legal guardian. This may involve the use of two consent forms: a parent/guardian consent form and a specific child consent or assent form (depending on competence).

Accessibility for all

You may need to make provision for participants who are not fluent in the language of the

information sheet and consider how to deal with challenges such as low levels of literacy. For example, you may choose to have information sheets translated into other relevant languages and/or use translators when seeking consent. Rather than providing the information in written format, it may be also delivered verbally.

If the intervention forms part of normal classroom activity and practice, for example, changing teaching, learning or assessment methods, using a new resource or mobile technology, then the students do not need to consent to participate in the intervention

Consent is required if you are collecting and processing (using) personal information about your students, even if students will not be identifiable in your research report. (e.g. questionnaire, interview, focus group, etc.) In most instances, the response to question 1 of the ethics section of your proposal will be ‘YES’. You will need to provide details of how the data will be used and think about how the data will be securely stored, and how students will be protected in the writing of your research

So, ensure that you:

• Speak to your Mentor or placement lead, before you begin to share your ideas and get their insights

• Make it clear on the title page that the research is yours and that it cannot be incorrectly perceived as originating from the institution

• Include a statement about the confidentiality of responses.

• State the purpose of your questionnaire in relation to the PGCE/Cert Ed programme of study

• Do not take co-operation for granted - even colleagues you have worked with for a long time may be reluctant. You should respect their doubts and fears

• Ensure you obtain informed consent from your participants (students, learning support colleagues, mentor and line managers, etc.) and provide them with clear information on what you are going to do with the data they have provided once it has been analysed. Make the limited distribution of the research report clear to them

• Respect confidentiality when writing up the findings by disguising roles and responsibilities, using pseudonyms and broad descriptions (such as a North-West College of Further Education) instead of actual names.

Checklist for ethics

1. Does the research abide by the laws and respect the cultural norms of the society within which the research is conducted?

2. Has approval for the research been obtained from any relevant ethics committee?

3. Have participants been supplied with sufficient information about the research?

4. Is participants’ personal data being processed? Do the participants need to provide their written consent to participate in the research?

5. Has the research been conducted with professional integrity (honest, objective, unbiased)?

6. Has the research avoided any misrepresentation or deception, if not has an explicit justification been provided?

7. Have the data been collected via legal and legitimate means?

8. Has the research avoided any intrusion into the lives of those involved?

9. Have the interests of the research subjects been protected throughout?

a. Avoiding stress and discomfort

b. Maintaining confidentiality

c. Protecting anonymity

d. Avoiding undue intrusion

10. Have reasonable steps been taken to maintain the security of data?

(Adapted from, Denscombe 2002, p.195)

Section Six: Analysis, interpretation, and presentation of evidence

Looking for evidence

Whichever data collection methods you decide to use, you will eventually be faced with the task of analysing, interpreting, and presenting this qualitative information. What is very important to remember is that the reason we are analysing data (remember that this means we are taking it apart and really looking into it), is that we are looking for evidence.

Initially we will look for all of the evidence that supports the research questions we had posed

Example: Exploring Assessment Activity

▪ We may have wanted to investigate why our assessment activities used with our learners did not accurately portray their real ability. This was our initial area of enquiry; it was what we wanted to explore more fully. At this stage we establish research questions that we want to explore.

▪ We imagined a way forward and changed the assessment activity for the better; we implemented it and tried it out

▪ We collected data about the changes we had introduced to see what was really happening now

▪ Then we analysed and explored that data to see what evidence it gave us. We were looking initially for evidence of more reliable assessment.

▪ We then looked at the remaining data to see what evidence this gave us. We may have some surprises that we had not anticipated and it’s important to write about this evidence as well

▪ The evidence we find becomes the themes for the discussion in the research report.

Although, on the face of it, you could decide how you will analyse / interrogate this data afterit has been collected, many researchers have unfortunately found to their cost that, once they have chosen their analytical approach the manner in which the data has been collected makes it extremely difficult to implement. These barriers could be physical in terms of how the data has been recorded, or they may be methodological in relation to the way the data has been collected.

In some cases, the data collected is, at best, sparse and at worse completely missing, from the very area where information is needed to build on previous concepts and principles. The obvious message here is that it is important to know as clearly as possible beforethe implementation of the research project, the questions which need answering and the sort of data that would be most useful in order to facilitate a method/s for analysing and interpreting data.

The difficulty facing qualitative researchers is that there is no ONE way to analyse, interpret and present data. Instead of going into detail here of the various options for analysing, interpreting and coding data you are strongly advised to read the following sections in key texts which provide good discussions of the processes that inform good data analysis. Tutors will also provide input and support on data analysis in week five of this module.

❖ Chapter 13 ‘Interpreting the evidence and reporting the findings’. In, Bell, J (2014) DoingYourResearchProject:Aguideforfirst-timeresearchersin educationandsocialscience(6th edition). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

❖ Part 3 ‘Data Analysis’. In, Denscombe, M. (2017) TheGoodResearchGuide(6th edition) Maidenhead: Open University Press

These are not the only useful texts that will help you explore methods of data analysis – tutors will share others with you and you are encouraged to explore your own ways of data analysis and presentation of data.

For your action research model we advocate that you use a thematic approach to analyse your data – where you will list, code, and slice your data, to make sense of it and find the evidence to answer your research questions.

Thematic analysis

There are six steps to the process:

Step 1: Become familiar with the data. This is really important: If you are familiar with your data you will find it much easier to analyse.

Step 2: Generate initial codes Looking at each data collection method in turn, group similar ideas and responses together and give them a name (a codename) e.g. ‘motivation’, ‘ambition’ ‘better behaviour’ ‘increased engagement’, etc

Step 3: Search for themes. Next look your coding for your data collection methods and slice throughthem: Which codes are appearing in one or more of your data collection methods? Group these things together to become ‘themes’.

Step 4: Review your themes. Do your themes make sense? Have you included everything? How many themes do you have? Could some be combined together?

Step 5: Define themes What do the themes relate to? How do they compare to your research aim and questions? (You set out your aim and questions in your statement of intent.)

Step 6: Write-up your findings and use your themes/findings to answer your research questions

A template has been developed (Exercise seven in the activities section of this handbook) to show you how to undertake thematic analysis and allow you to practise identifying themes that emerge in your research and then to classify the data in order to facilitate analysis.

It can be really helpful to share your data with your peers, colleagues, and tutor, to see what codes and themes they can identify in your data. (Be aware of confidentiality if you have sensitive data sources and make sure participants cannot be identified).)

Finally, remember that this project is designed as a vehicle for you to demonstrate your understanding of how to carry out an action research project and use a variety of data collection methods. So do not despair if your data does not provide you with the evidence you had hoped for. This is often the case in research and, providing that you can discuss the reasons for these shortcomings using appropriate references to sources, you will be able to turn what appears to be a weakness in your project into a strength, because you will be provided with a focus for an

insightful discussion about your action research methodology.