Paul Burlin’s move to Santa Fe, subsequent his participation in the 1913 Armory Show in New York, would herald a new era of modernism in New Mexico. The Armory Show, he later recalled, had little impact on his work and yet he was affected; simultaneously unsettled and yet galvanized by the event. As time passed, the new ideas and inspirations Burlin experienced at the Armory Show and in other established galleries in cities across America began to appear in his paintings.

Returning to the Southwest to live, he drew inspiration from the culture and the landscape. Like many modernists of the day, Burlin was fascinated by so-called “primitive” art, particularly the designs and palette of the Native cultures he encountered in New Mexico. In 1917 he met and married Natalie Curtis, a highlyregarded ethnomusicologist specializing in Native American music.

In 1921, Paul and Natalie Burlin moved to Paris as part of an exodus of expatriate artists responding to the provincialism of America after World War I, exemplified by the hostile reaction to his abstract work and other modern art. In Paris, Burlin found himself in the cultural center of modern art. He studied European abstract artists, working with the Cubist Albert Gleizes, and further developed some of the intellectual and symbolic elements that he had begun in the Southwest.

Later that year, Natalie was killed in an automobile accident. Burlin was devastated. He moved back to the Southwest, but found no solace there, and soon returned to Europe. He continued to live in Paris until 1932, when he moved back to the United States in the midst of the Great Depression to work for the WPA. During this time, Burlin’s work tended toward social-realism, experimenting with political and urban themes. Throughout the war, Burlin employed themes of war and persecution, drawing much of his inspiration from Picasso’s war paintings.

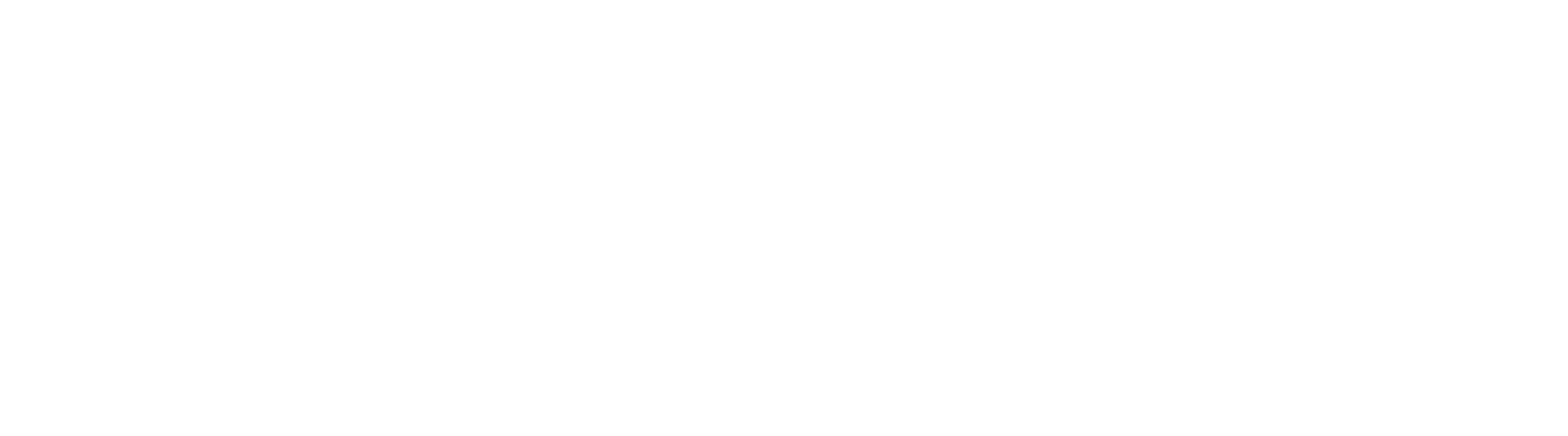

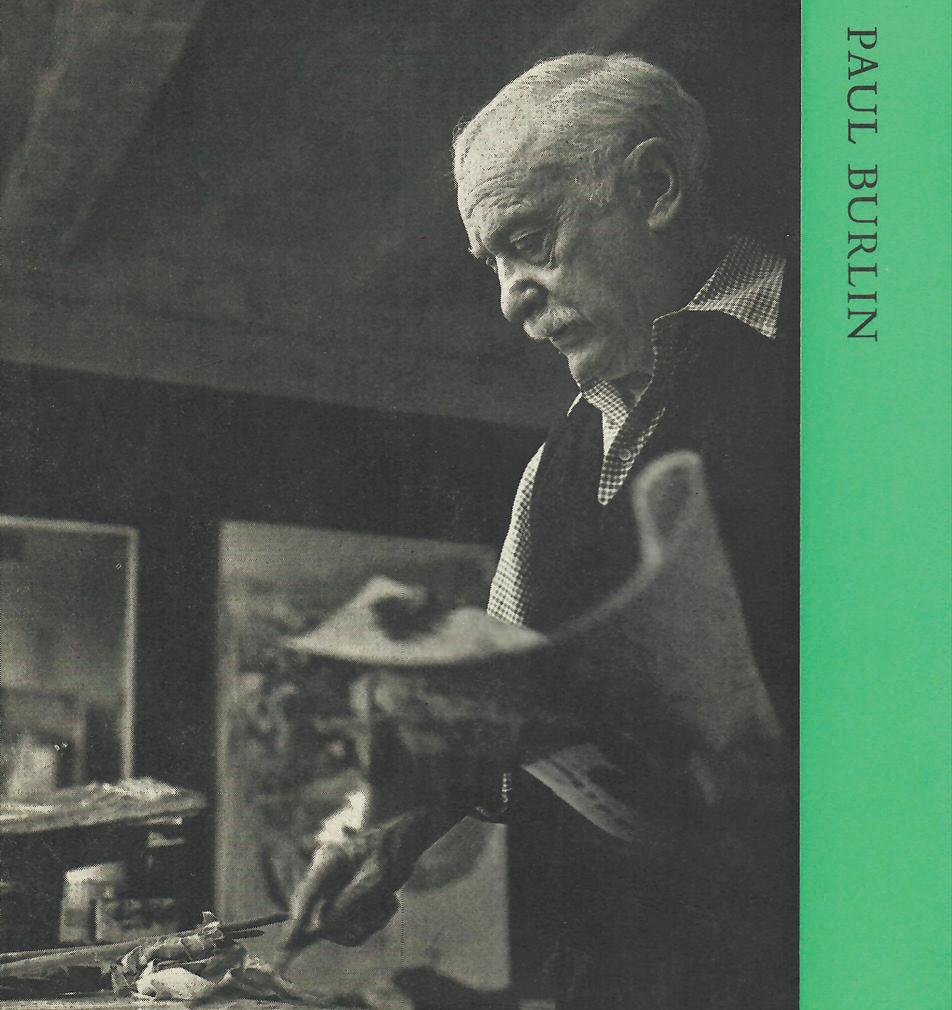

Later years would see him visited by visual difficulties, undergoing early cornea transplants in the mid 1960’s, and at times legally blind but,. . . .still painting.

Endeavoring to calculate Burlin’s contributions to early modernism/expressionism in New Mexico onehundred and ten years after the fact is challenging, but it can be said Burlin was not only the first Armory Show participant to arrive in New Mexico, but the earliest painter of Modernism in the region.

The exhibition and catalogue titled “ Transformation of Spirit to Pigment: Harmony in Chaos ” celebrates Paul Burlin’s mature works, ca. 1950 –1969; not only his most prolific and productive period but arguably his most poetic, with numerous canvases from the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Museum of Modern Art exhibitions. This publication is the most extensive biographic chronology of the artist to date including his exhibition history, literature and publications.

We gratefully acknowledge the participation and support of the Paul Burlin Art Trust and the immediate and extended family of Paul Burlin.

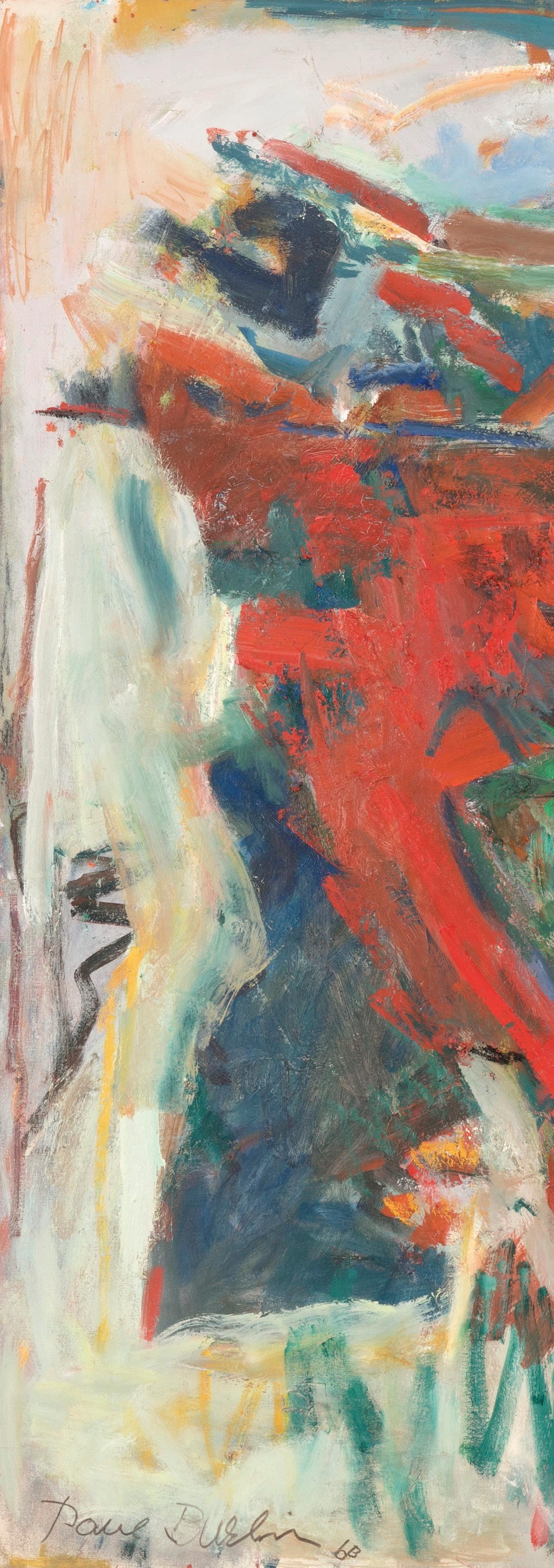

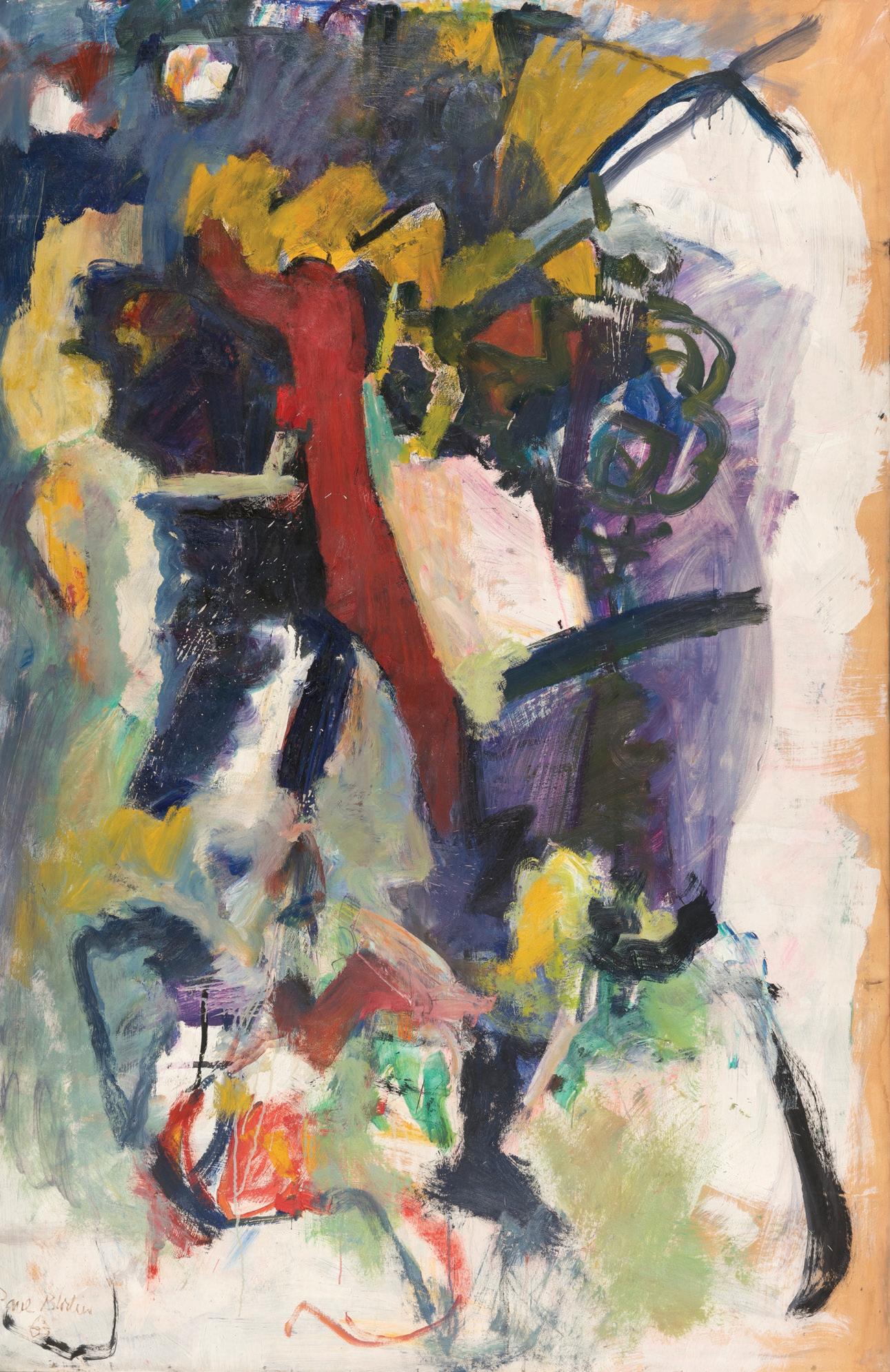

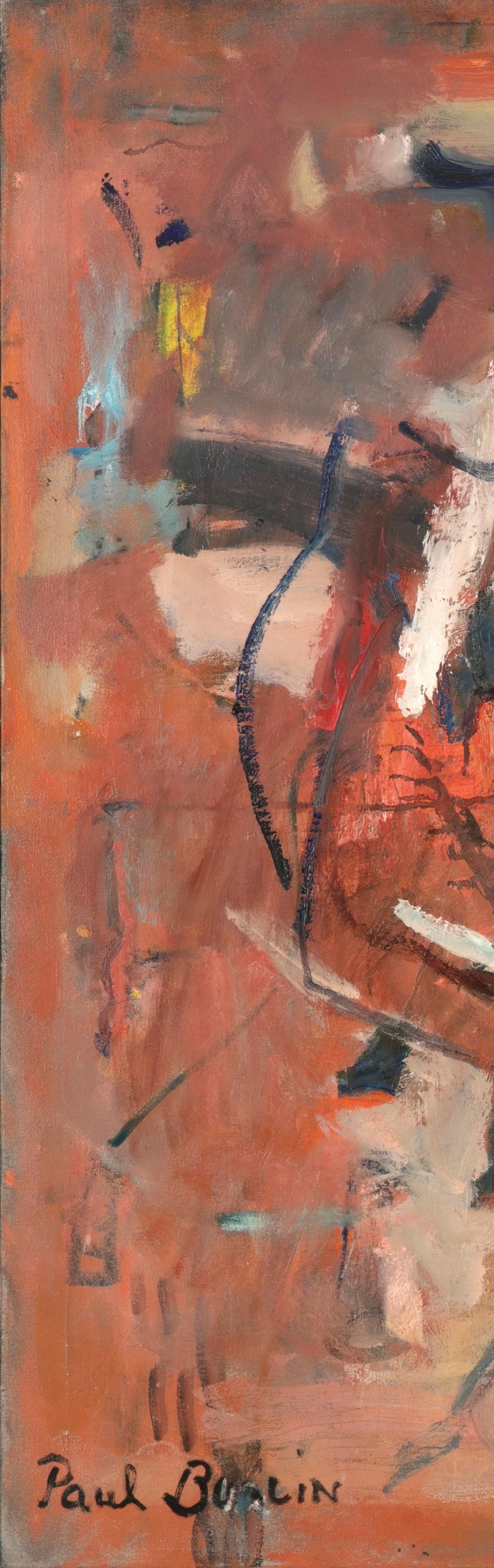

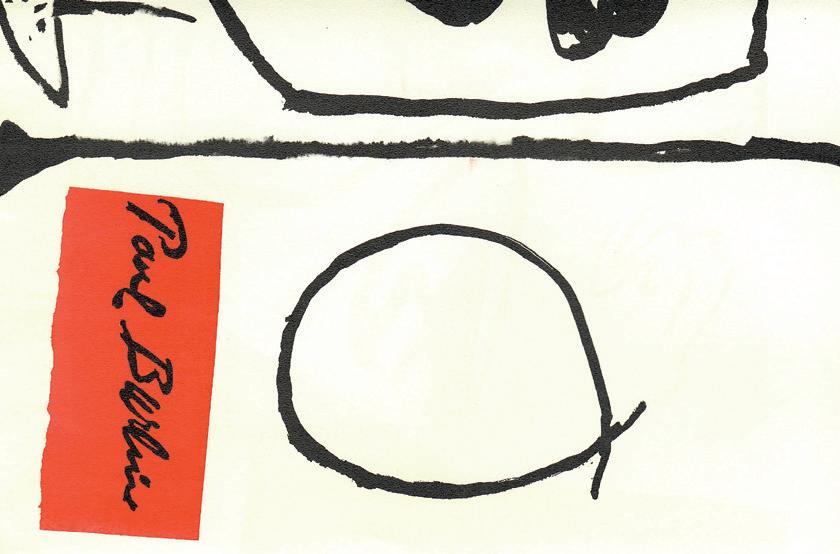

Vincent Vallarino Vallarino FIne Art John Wright Schaefer Peyton Wright GalleryCHICAGO, 1960

OIL ON CANVAS

48 X 72 INCHES

SIGNED & DATED LOWER LEFT

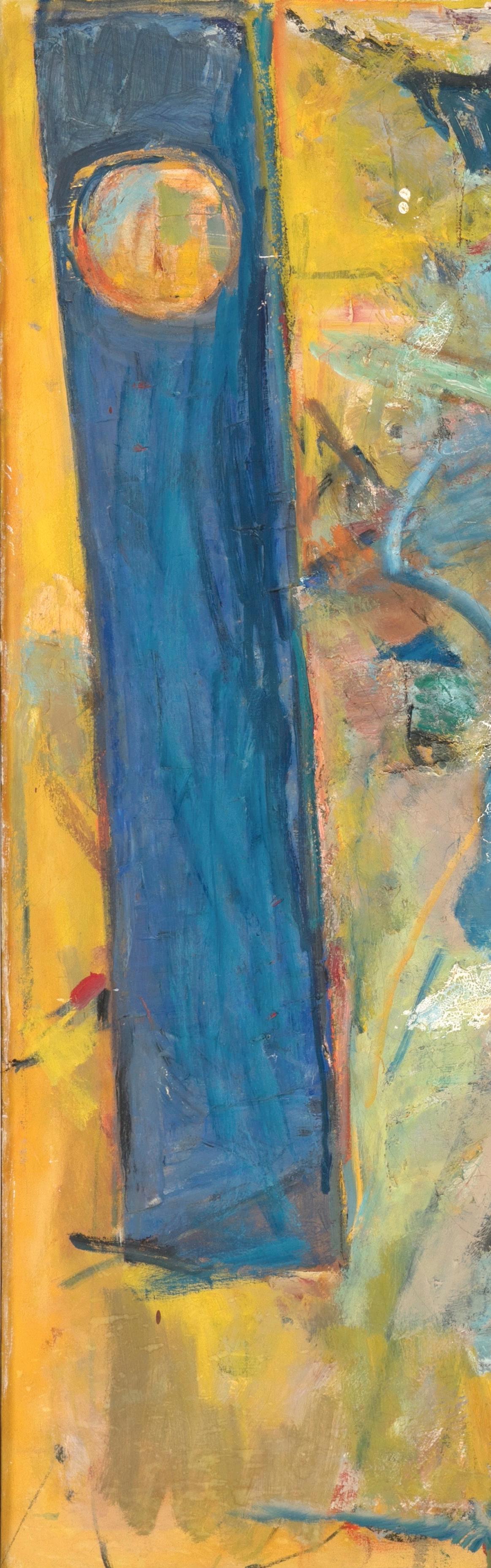

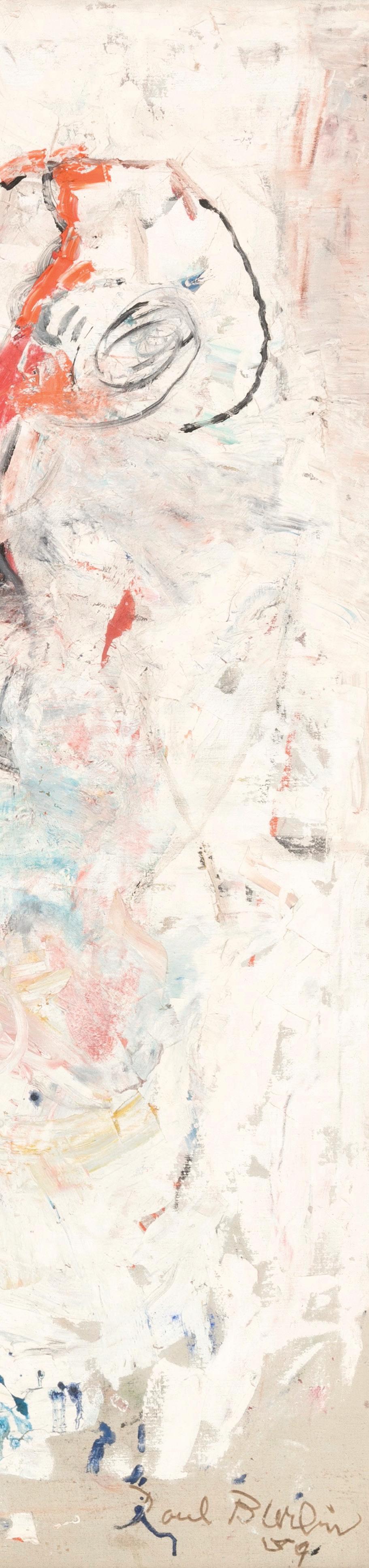

The raw intense complementaries in the recent canvases of Paul Burlin are painted impetuously, yet they well up from deep within themselves, coalescing into mobile forms that make the limitless space dense. Color, that most enigmatic of pictorial elements, rather than line, is used to create structure. In It Is (1959), the image looms from active bluish and greenish whites. A massive centrally located yellow quadrilateral halved by a snaking blue, slides precariously to the left as it thrusts forward aggressively from blue and red. Suspended above it and to the right are tumbling brown and blue fragments, and below, a configuration of calligraphic signs—emergent forms—in the path of a red that bursts in from the right. Burlin takes his stance in chaos but does not succumb to it. Although the off-balance complexes of open forms are in unceasing flux, the shapes, each imbued with its own emotional and pictorial meaning, strain to regroup themselves about some still unknown center of gravity. One senses that Burlin once had more definite ideas about equilibrium, but relinquished them. All that remains is the yearning for order and the hope that it is achievable. Found in the file of miscellaneous papers that he keeps is a quote from Ortega y Gasset: “There is but one way to save a classic; to give up revering him and to use him for our own salvation—that is to lay aside his classicism . . . to make him contemporary, to set his pulse going again with an injection of blood from our own veins, whose ingredients are our passions and our problems.” The turbulence in Burlin’s pictures is a sign of a new attitude to life, of a changed relation between the individual and his environment. As he wrote in 1954: “The artist reflects his age. Raphael had the serenity of the Renaissance behind him . . . a calm immutable balance. This was the period of a belief in man and hence a period of distinguished portraits, for the portraits of the Renaissance were the embodiment of an idea. Today we have no such ideas….We have lost our face….We live in an age of treacherous, harrowing notions of mutability, death and decay. . . . All of the old realities have dissolved . . . all rigidities of form disappear and enter into a new metamorphosis.” Burlin has dedicated himself to finding his “face” —not a particular set of idiosyncratic features, but the changeable physiognomy of a contemporary man.

The sense of dynamic “metamorphosis” has become more real to him than fixed impersonal abstractions that can no longer embrace the wholeness of the individual. The rejection of predetermined ideas about art and life has compelled Burlin to begin at the beginning, to re-examine the elemental motives of painting. Like many of his contemporaries, the so-called Abstract-Expressionists or Action Painters, he has sought for certitude, for self-realization in the immediate process of creation, the powerfully felt esthetic experience—the fusion of subliminal impulses and conscious action. The choices that Burlin makes while working—the gestures and responses to gestures; the coloring, shaping and locating of pictorial elements, the organization of space– are dictated by a passionate yearning for authentic self. He feels conscience-bound to follow his vital impulses wherever they may lead, refusing all that is arbitrary, unessential and contrived. “I loathe the manipulation of art and all of the little niceties and clevernesses. I am against the pastiche artists. They can’t dare to fail. They haven’e got that kind of guts.” Painting for Burlin is a moral act— “the absolute conviction that this is how it should be and no other way.” The finished work bodies forth the substance of the artist, but in its own autonomous terms. It is not complete until it becomes an organic entity with a presence as alive as that of the artist for which it is a symbol. Although Burlin has discarded comfortable ideas about what art is supposed to be, outworn conventions and formulas, he brings to painting more than half a century of experience as an artist. Some of his knowledge has taught him what he doesn’t want to do—interlock closed forms in the Cubist manner or treat color in terms of dark and light values— but his profound command of the mechanics of painting, his comprehension of the potentialities of pure color, have enabled him to clarify what he is after. He wrote in 1951: “For the artist to give rein to his instinct and yet to master it is the quintessence of expression.” It is this combination of freedom and audacity, of discipline and craft, that has made Burlin one of the most powerful and distinctive of contemporary colorists. Like the man himself, Burlin’s “selfportraits” are a lively mixture of robust poetry, tough unsentimentality, elegant flamboyance, irascibility, wit. They are self-assertive with a forthright sincerity that verges on rudeness. Burlin claims that he is dissatisfied with a picture unless he finds in it “‘an arrogance that says to hell with all reasonableness but this.” The social value of Burlin’s works lies precisely in this kind of self-affirmation (and he is constantly concerned with their social value).

WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS

WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS

The “we” in his statement “we have lost our face” becomes more than a literary convention meaning “I.” Burlin means to challenge the prevailing mass stupor which threatens the individual with a loss of identity. His paintings “yawp” because he intends for them to stand apart from the millions of superficial images that bombard and deaden the retina. He means to force his works into life, to create “‘a stir in the world” as Robert Henri put it, to proclaim that man is not an insignificant integer in some anonymous public without will or aspiration, but that man can realize himself. Burlin’s individualism is rooted in the heritage of American dissent. As a young man in the early years of the twentieth century, he was affected by the Progressive movement (he worked on “Delineator” when Theodore Dreiser was the editor) and by its artistic counterpart, the Ash Can School (it was William Glackens who invited Burlin, then 27 years old, to exhibit in the Armory Show of 1913). In his thinking about art, Burlin was more adventurous than the urban realists who continued to work in anachronistic pre-Impressionist styles, more sympathetic to the modernistic tendencies of Alfred Stieglitz whose Gallery 291 he frequented. However, he did assimilate a number of insurgent attitudes, many of which he still holds. For example, the Eight stood for “truth” as against “beauty”; for “life” as against “art”; for the “real” as against the “artificial.”

To Burlin, these attitudes have a particularly American flavor. He thinks of himself as an American artist, but with ambivalent feelings. On the one hand, he delights in the American’s energy, crudeness and dynamism, and in the fact that the artist here is not weighed down with the aesthetic baggage of his European counterpart. On the other hand, he is appalled by the backwardness, smugness and philistinism that he finds so prevalent in the United States, and has waged war against the slick, the cautious and the commonplace through his painting, his teaching and in the public arena. In lectures throughout the country, he has repeatedly stressed that “the artist is a barricade in the face of vulgarity and decadence.” He has fought to get society to incorporate the artist as “a valuable social unit,” but on his own terms. Shortly after the Armory Show, Burlin went for a trip to the Southwest (before the founding of the Taos and other art colonies). Fascinated by the inhuman drama of the desert, he decided to remain there. He lived in Santa Fe until 1920, but maintained contact with the New York art scene, exhibiting periodically at the Daniel Gallery. The Armory Show had made a profound impression on him, but he was not yet ready to commit himself to Fauvism or Cubism, although the influence of Post-Impressionism began to manifest itself in his painting. Like many of the European pioneers of modern art, Burlin went through an intensive preoccupation with primitive art. In New York, he had been stimulated by the Marius de Zayas collection of African sculpture, but he did not fully appreciate the power of primitive art until

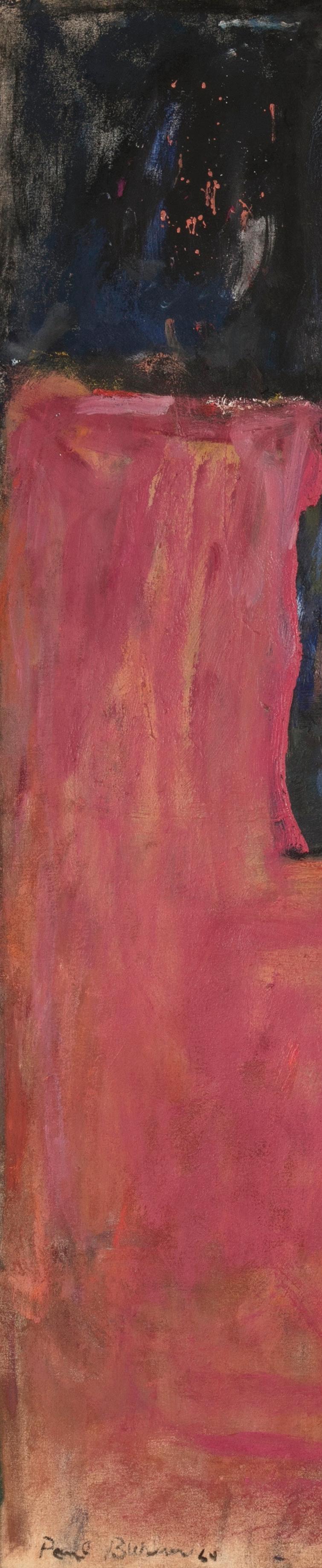

BORGENICHT GALLERY, NY, 1975

“I have been interested in the strange hard jewels hidden deeply in nature; forces evocative, distant and unrelated to life...dreams of bygone ages... beautiful, shining and cold....and yet forces that man uses.”

PAUL BURLIN, 1953PAUL BURLIN,

he encountered the forceful geometry and brilliant color of American Indian decoration. Unlike most advanced artists in Europe whose contact with native cultures was limited to the works of art, Burlin with his wife, Natalie Curtis, a distinguished musician and ethnologist (her “Indian Book,” Harper Bros., 1907, remains a classic study of the music and poetry of these people) got to know the desert tribesmen intimately.

During this time, Burlin began to paint portraits of Indians. Guy Péne Du Bois, editor of “Arts and Decoration” and one of the organizers of the Armory Show, in an article written in 1917, placed Burlin among those “men who speak of primitive force as a religious precept. Mr. H. Paul Burlin .. . belongs to this straight from the shoulder group of painters. [His] pictures [are] executed with straight arm motions, which does away with sensitiveness, which includes a human figure with a few strokes of the brush, blind to local incident, and he paints all of . . .[the] figures in the same preconceived color harmony. Educated primeval instinct this — worshiping the wooden god of a new religion. But something will come out of it nevertheless. It is required only that artists worship, which means that what they worship matters very little.” In 1916, Burlin visited the Colorado Fuel and Oil Company in Pueblo. He later wrote of this experience: “I instinctively made an abstract collage of machinery. I realized that the force, the smooth beauty and terror of the machine could only be expressed in abstract terms.” Burlin did not become an abstract artist at this time, but the possibility of creating such art was not lost on him. In 1921, as a result of the bitter reaction against modern art in the years immediately following the first World War, Burlin went to Paris as one of the Expatriates. Earlier that year, friends of his threatened to sue The Philadelphia Morning Telegraph and forced that newspaper to apologize for the violent attack by its critic on a painting he exhibited in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. As a result of the threatened lawsuit, a symposium of physicians, meeting at the Philadelphia Art Alliance, diagnosed modern art as insane. This was but one example of what Burlin calls “the palsy of the spirit” that prevailed in America at that time. It was the return to normalcy, to chauvinism and provincialism, and the increasing hostility to creative artists that caused so many of them to go to Europe in search of a sympathetic milieu. Burlin’s trip to Paris was prompted by a desire to pick up the threads of the Armory Show experience, the impulse of a restless man to go where things were challenging and alive. In Paris, he shared a studio for a time with Albert Gleizes who admired his paintings. The Cubist indoctrination that Burlin received from Gleizes was a valuable one, but he reacted against the older artist’s attempt to codify Cubism into a set of formulas, an attempt that Burlin felt spelled the death of Gleizes as a painter.

1926

“We hear much of the need of communication in painting, and yet like a face, a painting changes as we get to know it better and becomes a mirror for our thoughts. To venture beyond nature or the merely visual, to go beyond personal experiences becomes a new creative enrichment.”

PAUL BURLIN, 1953

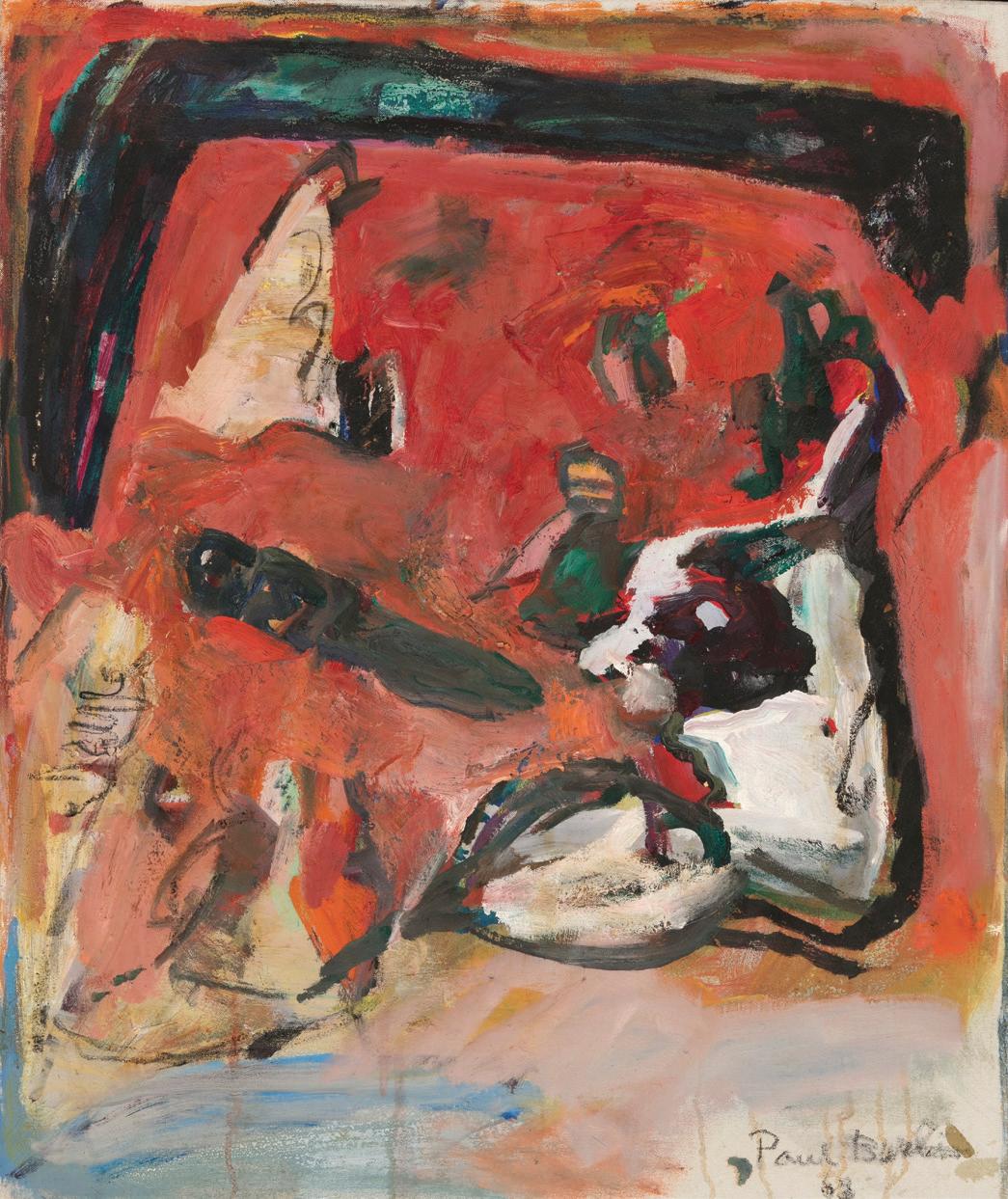

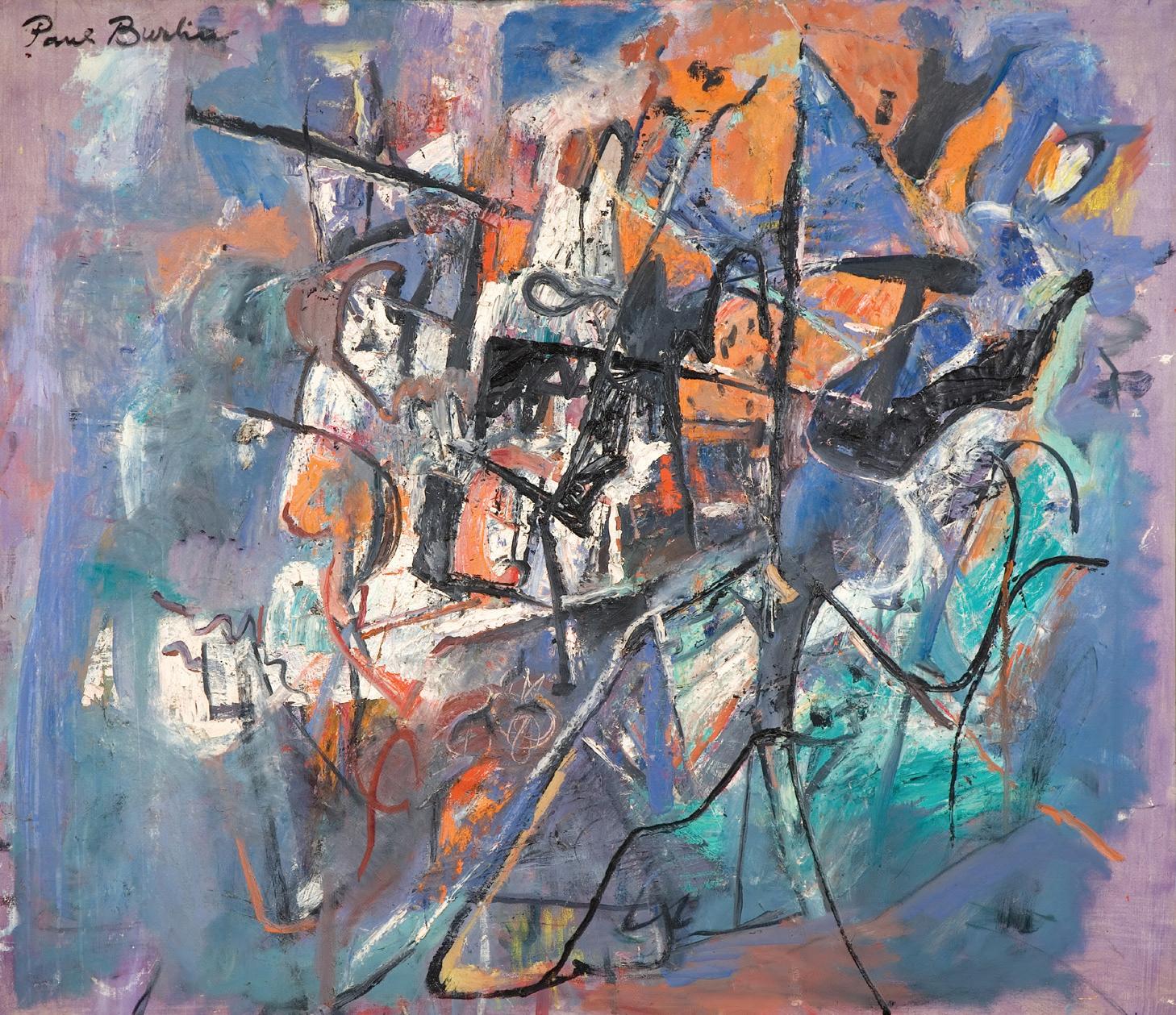

OIL ON CANVAS

54” X 60”

SIGNED LOWER LEFT

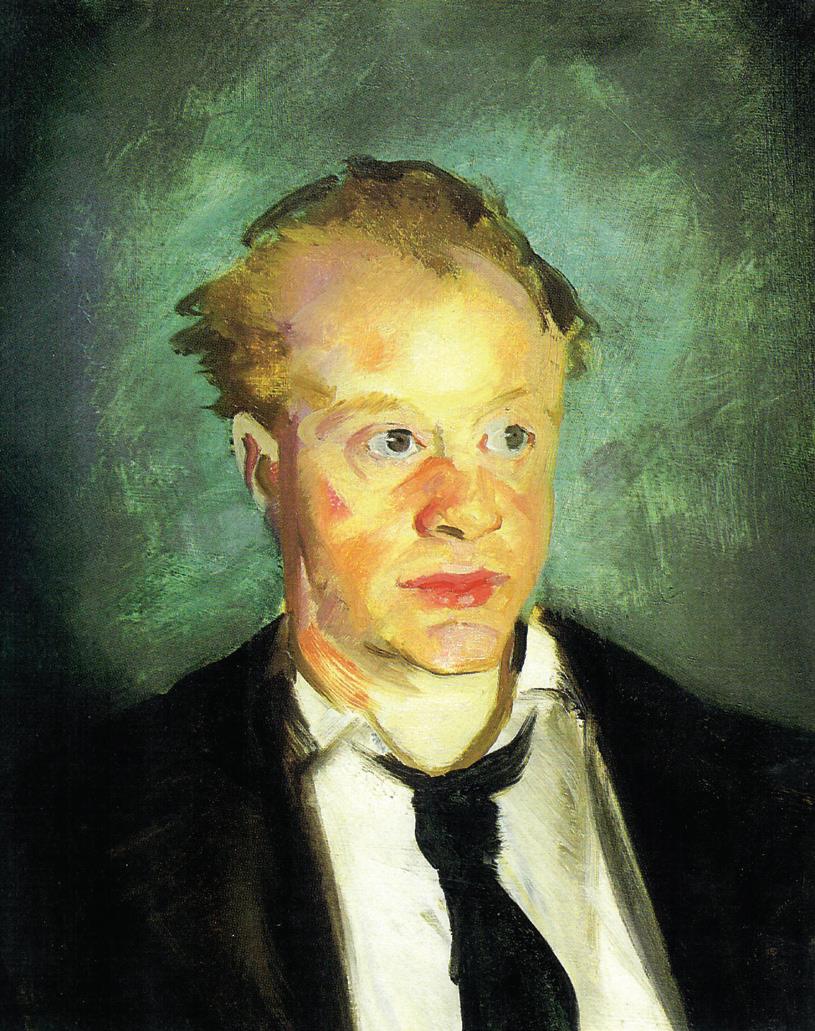

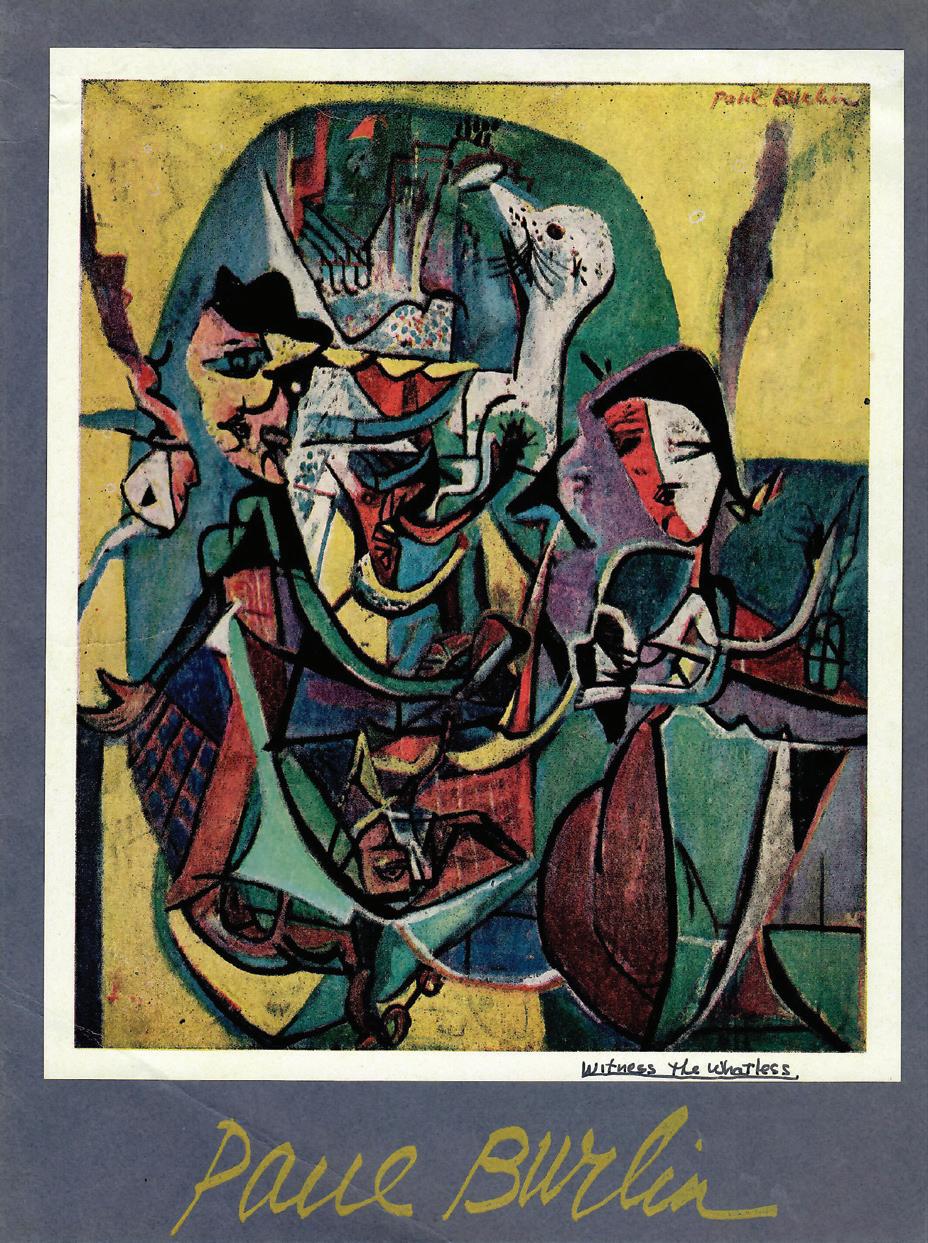

Burlin also got to know many of the other artists of the school of Paris. Leo Stein became a close friend and wrote the introductory statement for one of Burlin’s projected shows in Paris. Despite the excitement of the Parisian art scene, the overall impression that remained with Burlin after his twelve-year sojourn there was that he felt like an outsider, an alien. The need for roots caused him to return to America in 1932. During the middle and late 1940s Burlin began to pay less attention to subject matter and more attention to the expressive possibilities of painting in itself. He turned to mythology for themes but was increasingly concerned with the daemonic spirit of myths which he tried to infuse into the act of creation. Painting for him became a kind of incantation. In the brochure for his 1946 show, he wrote “The magic itself of the painting aims to destroy visual reality and the primitive colors shape themselves into a reality of their own.” The example of Kandinsky’s early improvisations was important in Burlin’s development at this time. He was stimulated by Kandinsky’s audacity—his daring to base his pictures on “inner necessity” alone, and his creation of a subjective, intangible space so radically different from that of past art. He was also attracted by Picasso’s barbaric paintings of women in the 1930s. These elements are increasingly felt in Burlin’s own canvases, in the emotional distortions and cacophonous complementaries. In “Young Man Alone With His Face” (1944) all of the pictorial attributes found in later abstractions are already in evidence. In the early 1950s, Burlin carried his Expressionism into abstraction. The world of natural appearances was completely swallowed up in the vehemence of the painting. In this sense, Burlin can be called an AbstractExpressionist in a way that many artists now classified under the label but who arrived at the new art via Cubism and Surrealism cannot. The evolution in Burlin’s work was gradual and coherent; it lasted over a period of a dozen years. His change was not a breakthrough, but an attempt to avoid being trapped by a style he had already achieved. The new approach offered him fresh points of departure, a more direct and immediate method of arriving at intensely personal images.

Burlin’s turn to abstraction took place when he was approaching his seventieth year, a testimonial to the youthful outlook of this artist. His constant search and development has not stopped to this day. “Quiescent Monster,” one of Burlin’s recent pictures, has a novel massiveness and simplicity. The violent carmine and green expanses suggest uncharted continents that have yet to be explored. The newness in Burlin’s painting is earned; it is the result of a lifetime committed to exploring all that which is vital in art.

Irving Sandler

OIL ON CANVAS

84” X 66”

SIGNED & DATED ‘59 AT LOWER RIGHT

Exhibited: American Federation of the Arts, New York, “Paul Burlin Retrospective”, January 1962-February 1963. Curated by Irving Sandler, the exhibition traveled to museums around the country, including the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Philadelphia Art Alliance.

Publications: Sandler, Irving, “Paul Burlin,” The American Federation of Arts, 1962, plate 27

OIL ON CANVAS

52” X 60”

SIGNED LOWER LEFT

“ PAUL BURLIN’S PAINTINGS ARE NOT LUSH, POETIC, OR LYRICAL. HIS ABSTRACT PAINTINGS ARE JUST TOO DIRTY TO BE POETIC, TOO MUDDY TO BE LYRICAL. THEY ARE IN A WORD, NASTY. ”

JOSEPH DREISS, ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM, ARTS MAGAZINE, SEPTEMBER 1975

OIL ON CANVAS

52 7/8” X 73 1/4”

SIGNED LOWER RIGHT

(DETAIL)

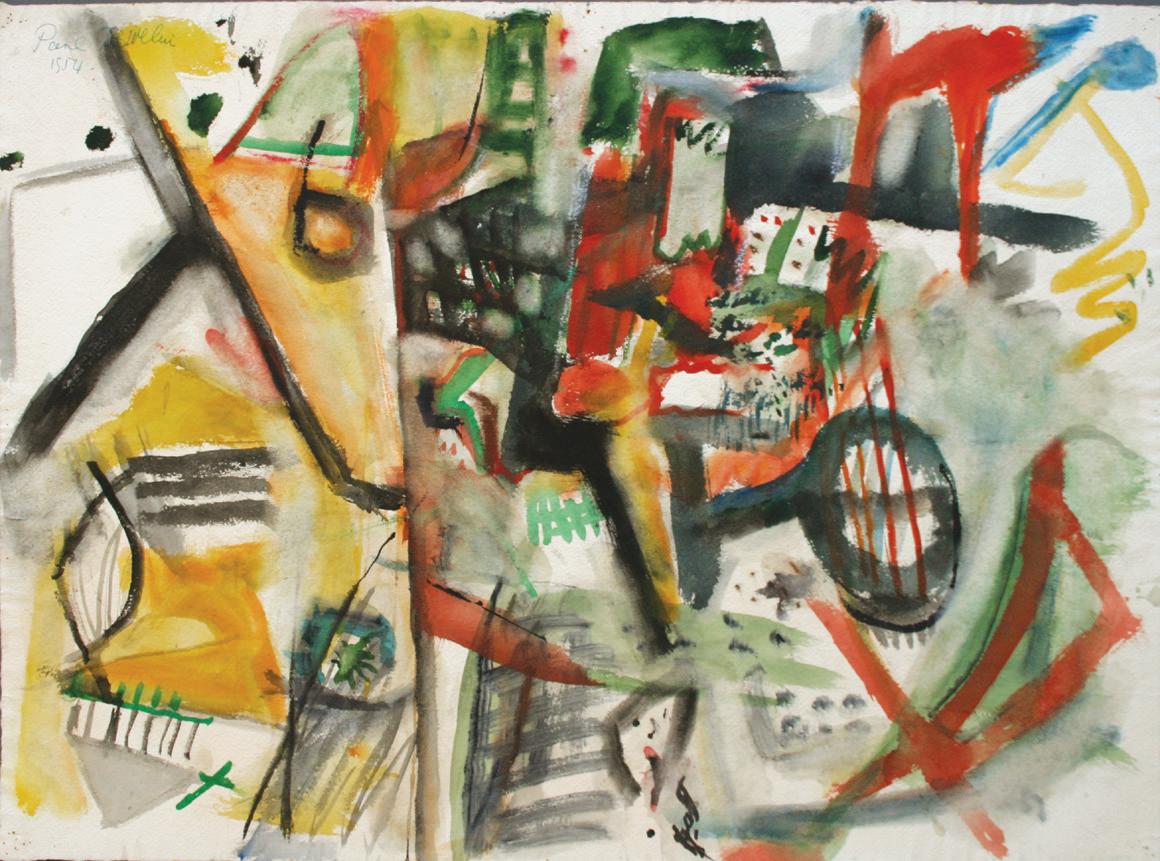

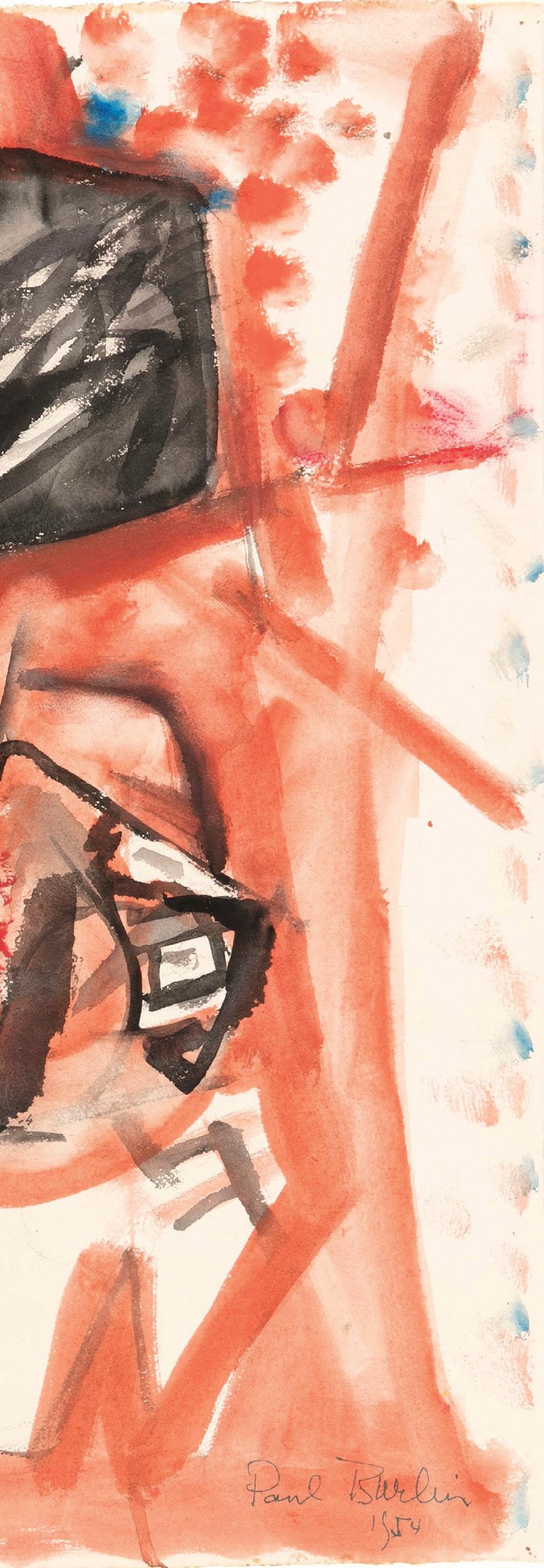

WATERCOLOR ON PAPER

22” X 30”

SIGNED & DATED 1954 AT UPPER LEFT

DECEMBER 1 - JANUARY 30, 1971

“My point of departure is a step by step organization of shape and color into a unity of design. And these shapes and colors are like floats on a limitless space because I preoccupy myself with making them exist in a two-dimensional world—not in a world of perspective, but in an infinity of space.”

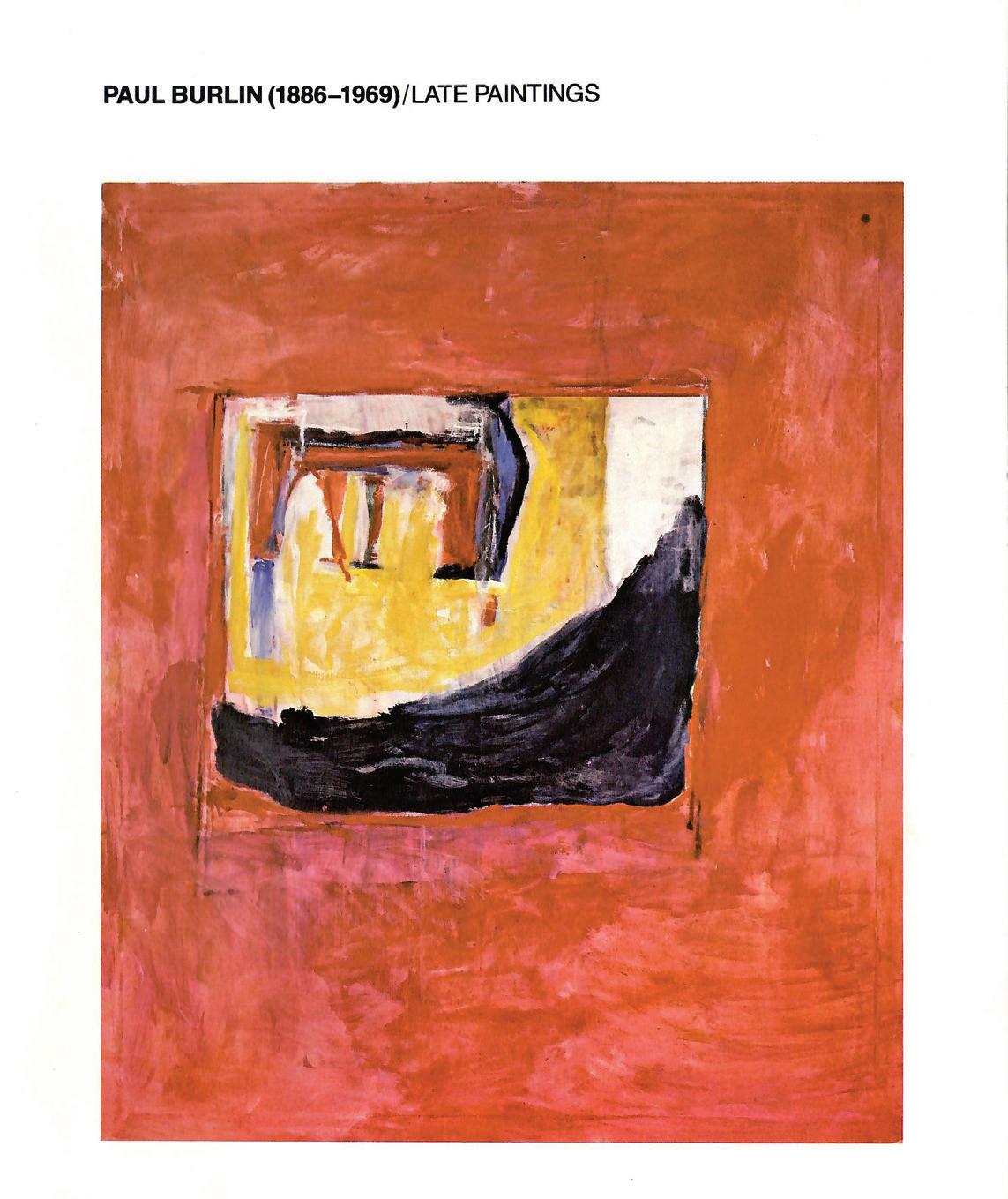

Virginia Allen, The Museum of Modern Art

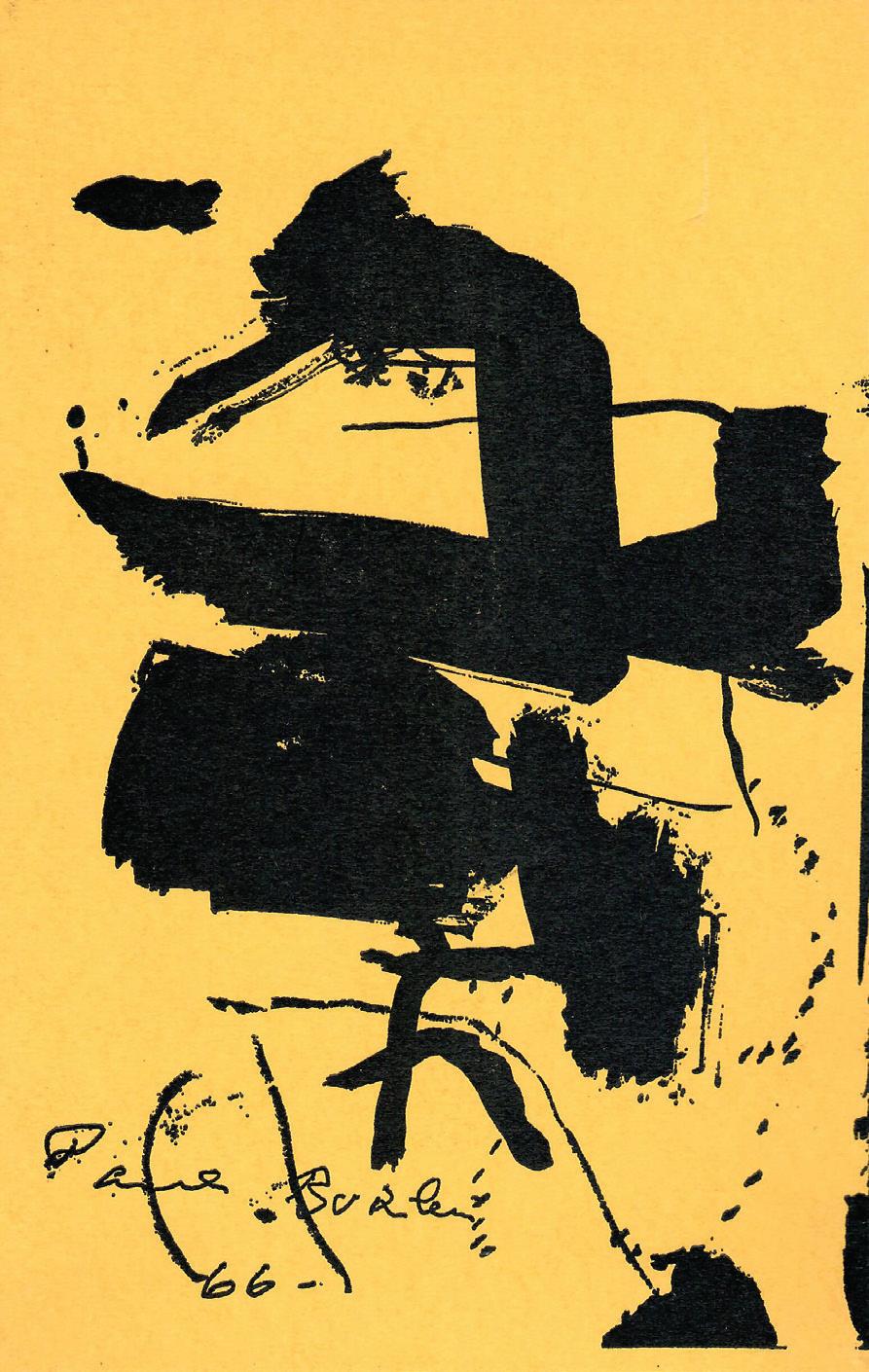

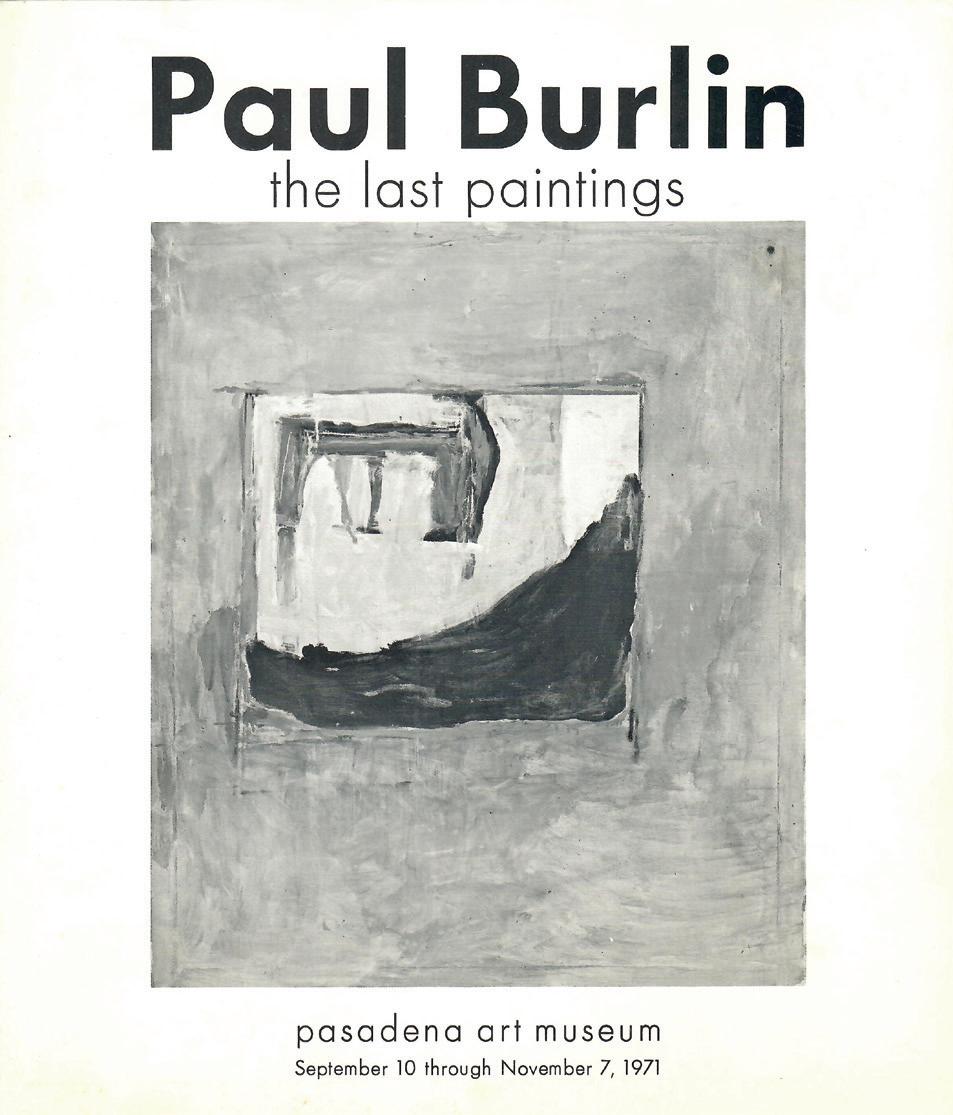

What Paul Burlin wrote in 1949 applies almost prophetically to the Series of 9, which he painted in 1969 during the five weeks before his death at the age of 82. This exhibition shows, for the first time, seven from this series, which evolved out of, but extends far beyond, Burlin’s work of the preceding decade. The paintings of the 1960s, already concerned with the pictorial rendering of limitless space, were charged with surface energy generated by the opposition of open, angular forms and the fluctuation of juxtaposed pure colors. In this last Series of 9, Burlin has calmed the turbulent surfaces and moved toward a new openness, simplicity, and serenity. The window shape—the primary pictorial element repeated throughout the series—may in this context have ideological and symbolic significance as well. The artist’s canvas is in a metaphorical sense his “window” onto the world. It is as if Burlin saw the essence of spatial infinity through his canvas and was thus able to achieve on its surface the climactic and authoritative synthesis of his life’s work. Burlin’s somewhat enigmatic career embraced the artistic developments of the twentieth century. He never became wholly a part of any movement or style, always retaining that degree of skepticism which allowed him to reject what could not be reconciled with his demanding criteria for painting. He was associated with the Ash Can School, participated in the Armory Show of 1913, and lived in Santa Fe, New Mexico from 1913 to 1920. His departure for Paris in 1921 was as much a retreat from the chauvinism and hostility of the American art world toward “modern” painting as it was a journey to the center of that European painting which had excited him in the Armory Show. In Paris, he absorbed the Cubist vocabulary of forms but rejected the rigidity and intellectualism of formal Cubist construction. Certainly the Impressionist/ Fauvist color tradition was to have more lasting influence and significance in his work. Returning to America in 1932, Burlin worked in the prevalent Social Realist Style of the Depression years. The 1940s saw his gradual escape from the fetters of subject matter, and he began to work Cubist forms in an increasingly expressionist manner. From the early 1950s, Burlin’s commitment to expressionism led him, like other painters of the New York School, increasingly in the direction of abstraction—looser forms, more painterly surfaces, and more expressionistic and sensory use of color. In spite of the obvious painterly gesture that links Burlin’s work to Abstract Expressionism, his aesthetic—like that of his contemporary, Hans Hofmann, whom he first knew in Paris—lay outside the movement’s mainstream. Both artists were substantially older than even the first generation Abstract Expressionists, their ties with the European tradition stronger. What is most remarkable in the career of Paul Burlin is that, with increasing age, he painted with increasing vigor, sought and discovered pictorial solutions that were intensely strong, and achieved in these final paintings an elemental solution that climaxed a lifelong quest.

The Museum of Modern Art first showed the work of Paul Burlin in 1930 - in the ninth exhibition of its young life. We are pleased and honored to present this small tribute on the fortieth anniversary of our association.

OIL ON CANVAS

84” X 66”

SIGNED LOWER CENTER

Exhibited: American Federation of the Arts, New York, “Paul Burlin Retrospective”, January 1962-February 1963. Curated by Irving Sandler, the exhibition traveled to museums around the country, including the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Philadelphia Art Alliance.

Publications:

Sandler, Irving, “Paul Burlin,” Whitney Museum / The American Federation of Arts, 1962, painting #24

OIL ON CANVAS

72” X 48”

SIGNED & DATED 1960 AT LOWER RIGHT

OIL ON CANVAS

54” X 60”

FRAMED: 55.75” X 61.25”

SIGNED & DATED LOWER LEFT:

PAUL BURLIN ‘60

Exhibited:

American Federation of the Arts, New York, “Paul Burlin Retrospective”, January 1962-February 1963. Curated by Irving Sandler, the exhibition traveled to museums around the country, including the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Philadelphia Art Alliance. (label verso)

Literature:

Irving Sandler,, Paul Burlin, American Federation of Arts, New York, 1962 no. 35 (illustrated)

Note:

Sold by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art to benefit future acquisitions

Burlin, Paul (Harry Paul):. American painter, 18861969

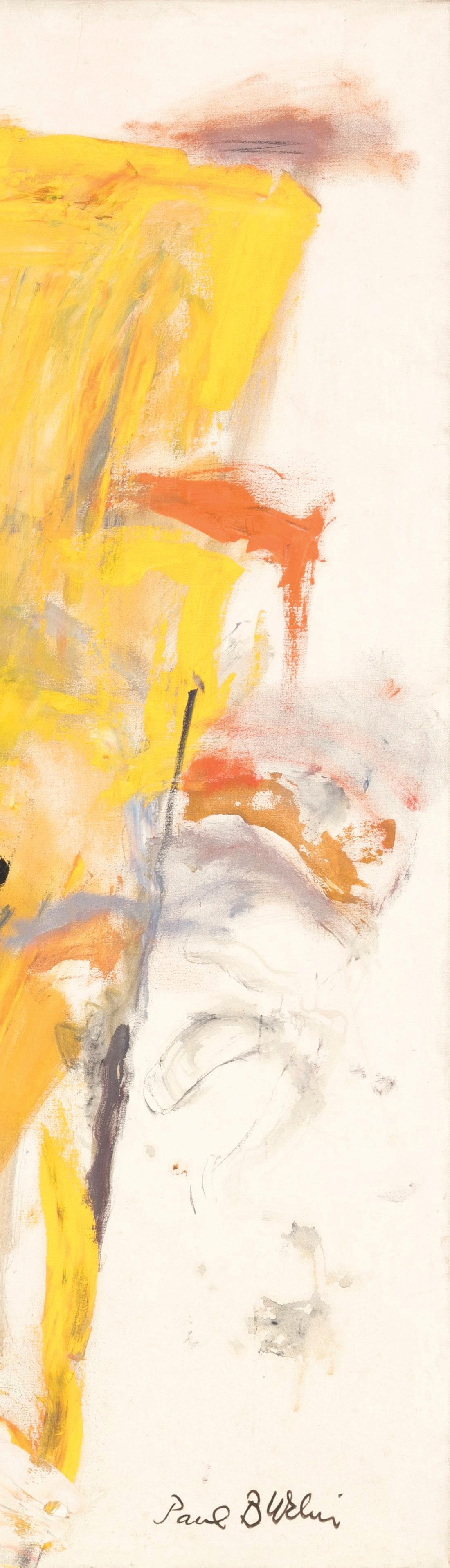

OIL ON CANVAS

72” X 48”

SIGNED & DATED

“

MY AIM IS TO MOVE FROM THE CHAOTIC OF THE UNSEEN TO THE SPIRITUAL. THE ENDING IS ABRUPT.” THESE TWO SIMPLE SENTENCES ARE THE SUMMATION OF BURLIN’S LIFE: A LIFE SPENT SEEKING THE EXPRESSION OF HIS EVOLUTION, FROM A MAN STRUGGLING WITH THE CHAOS OF HIS METAPHYSICAL NATURE TO THE ARTIST WHO, AT AGE 83, ACHIEVED HIS TRANSFORMATION OF SPIRIT TO PIGMENT. ”

GEORGE WHITNEY, ABRUPT ENDING: THE WORK OF PAUL BURLIN

OIL ON CANVAS

54” X 60”

SIGNED & DATED LOWER LEFT

Exhibited: University of Texas Gallery, 1964 Grace Borgenicht Gallery, NY

OIL ON CANVAS

48” X 72”

SIGNED & DATED LOWER RIGHT ‘60

OIL ON CANVAS

30” X 25”

SIGNED & DATED LOWER RIGHT

“ AS A MAN BURLIN HAS ALWAYS BEEN A SMOLDERING VOLCANO EMITTING FROM TIME TO TIME FIERY BLASTS IN IDEAS, WORDS, OR PAINT, BUT THE BLASTS, SO FAR AS I KNOW, HAVE NEVER ESCAPED CONTROL. HE BOILS, HE GENERATES HEAT THAT WOULD BURN ANY OPPOSING IDEA TO A CRISP; BUT HE NEVER BLOWS UP. IN CONTROVERSY HIS MIND IS QUICK ON THE TRIGGER AND HIS AIM IS DEADLY. ”

OIL ON CANVAS

48” X 54 3/4”

SIGNED LOWER RIGHT

OIL ON CANVAS

48” X 56”

SIGNED LOWER LEFT

“ HE TALKED ABOUT MATISSE AS THOUGH HE WERE DEFLOWERING LITTLE GIRLS. MATISSE DEFLOWERED MANY LITTLE GIRLS IN ORDER TO BECOME MATISSE. ”

PAUL BURLIN

OIL ON CANVAS

54” X 60”

FRAMED: 55.5” X 61.5”

SIGNED & DATED

LOWER ‘59 AT LOWER RIGHT

Exhibited:

American Federation of the Arts, New York, “Paul Burlin Retrospective”, January 1962-February 1963.

Curated by Irving Sandler, the exhibition traveled to museums around the country, including the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Philadelphia Art Alliance.

Boston College Art Gallery

Grace Borgenicht Gallery, New York, NY

Publications:

Irving Sandler, “Paul Burlin”, The American Federation of Arts New York, 1962, plate 21.

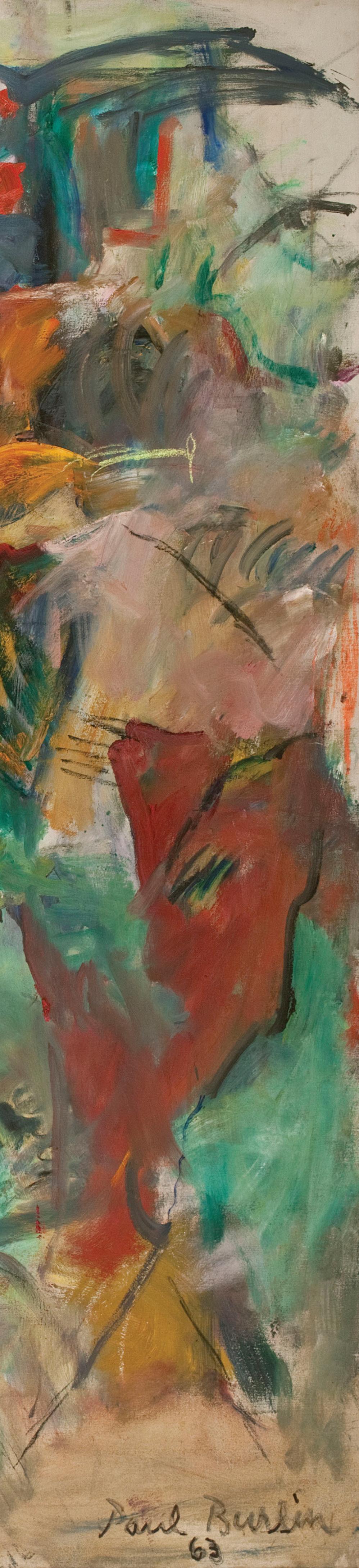

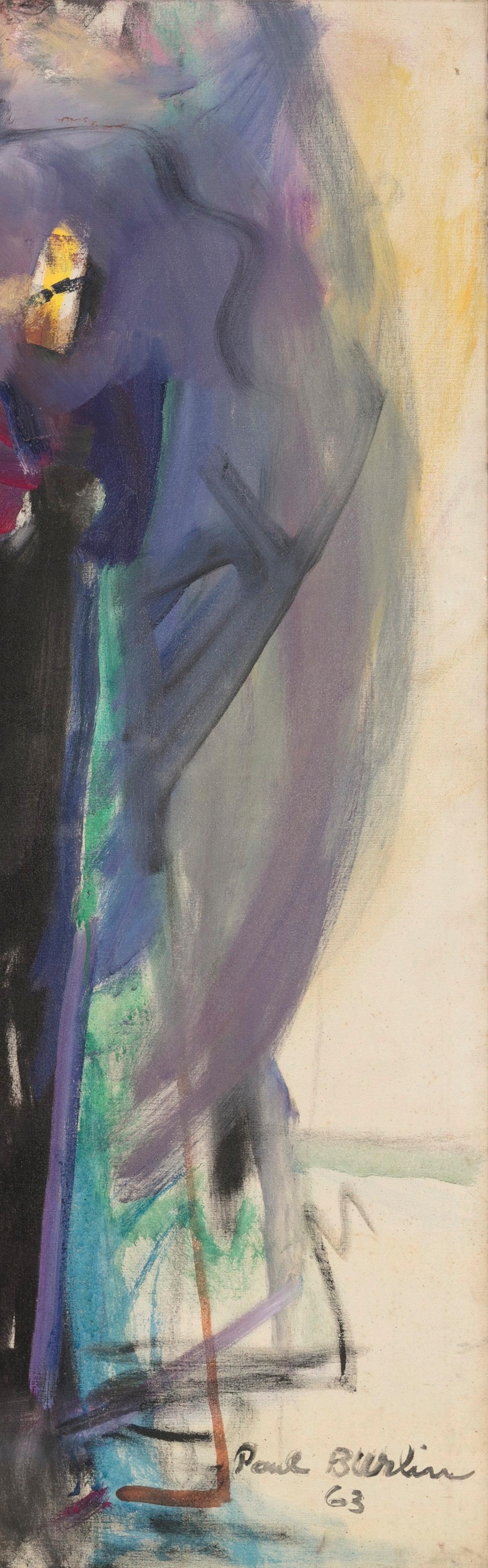

OIL ON CANVAS

80” × 70”

SIGNED & DATED ‘63

AT LOWER RIGHT

“ THERE ARE IDEA PAINTERS AND THERE ARE THOSE WHO THINK OR FEEL IN PAINT… WHAT INTRIGUES AND ENGAGES ME IS TO CAPTIVATE THE SENSUAL WITHIN A POINTED AESTHETIC… TWO CONTRARY ELEMENTS, ONE TO EXCITE, THE OTHER TO COOL. THE DUALITY RELEASES THE NEED FOR THINKING AND FEELING.

“AS A MAN BURLIN HAS ALWAYS DERING VOLCANO EMITTING FIERY BLASTS IN IDEAS, THE BLASTS, SO FAR AS ESCAPED CONTROL. HE HE GENERATES HEAT THAT OPPOSING IDEA TO A CRISP; BLOWS UP. IN CONTROVERSY ON THE TRIGGER AND HIS

RALPH PEARSON, EXPERIENCING

RALPH PEARSON, EXPERIENCING

ALWAYS BEEN A SMOL EMITTING FROM TIME TO TIME WORDS, OR PAINT, BUT I KNOW, HAVE NEVER BOILS, THAT WOULD BURN ANY CRISP; BUT HE NEVER CONTROVERSY HIS MIND IS QUICK HIS AIM IS DEADLY. “

EXPERIENCING AMERICAN PICTURES,

EXPERIENCING AMERICAN PICTURES,

OIL ON CANVAS

54” X 60”

SIGNED LOWER RIGHT

Exhibited:

American Federation of the Arts, New York, “Paul Burlin Retrospective”, January 1962-February 1963. Curated by Irving Sandler, the exhibition traveled to museums around the country, including the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Philadelphia Art Alliance.

Boston College Art Gallery

Grace Borgenicht Gallery, New York, NY

Literature:

Sandler, Irving, “Paul Burlin,”

The American Federation of Arts, 1962, plate 28

“ PAUL BURLIN WAS ONE OF THOSE DISTINGUISHED MEN WHO FOUGHT THE BATTLE OF MAKING ABSTRACT ART ACCEPTABLE AND POSSIBLE IN AMERICA. A FEW YEARS OLDER THAN MOST OF THE FIRST GENERATION ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISTS, HE EVENTUALLY ARRIVED AT A PUNGENT AND FORCEFUL ABSTRACT STYLE, THAT GREW MORE DARING AS HE GREW OLDER. HIS ART POSSESSED A KIND OF ENERGY AND FORTITUDE THAT TRANSFORMED ITSELF INTO FRONTAL COMPOSITIONS, SLOW RHYTHMS AND FULIGINOUS COLOR. THOUGH IT IS DIFFICULT TO SPEAK OF “HONESTY” AS AN ESTHETIC QUALITY, THE WAY IN WHICH HIS ART EXPERIENCED ITS PROBLEMS COULD CERTAINLY BE SEEN AS A MATTER OF MORALITY AND CONSCIENCE. ”

WATERCOLOR ON PAPER 22” X 30”

SIGNED & DATED

WATERCOLOR ON PAPER

22” X 30”

WATERCOLOR ON PAPER

22” X 30”

SIGNED & DATED LOWER RIGHT

“ FREE FROM ALL EXPRESSIONISTIC NIGGLING, THE PAINTINGS LOOK LIKE THE WORK OF A YOUNG MAN. PERHAPS THEY WERE SPURRED BY THE IMMINENCE OF DEATH, OR MAYBE IT WAS A MATTER OF THE CENSOR IN THE BRAIN RELAXING, AS IT OFTEN DOES IN OLD AGE. WHATEVER THE REASON, BURLIN DIED, IF NOT A MAJOR PAINTER, A FULLY REALIZED ONE. ”

VIVIEN RAYNOR, THE NEW YORK TIMES, FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 11, 1981

OIL ON CANVAS

72” × 48”

SIGNED & DATED’63 AT LOWER RIGHT

OIL ON CANVAS

44” X 50”

SIGNED LOWER RIGHT

“ BURLIN’S NAME IS NOT GENERALLY IDENTIFIED WITH THE 1950S AND 1960S; NOR ARE HIS PAINTINGS OF THAT TIME WELL-KNOWN, BUT THEY SURPRISE THOSE WHO DO KNOW THEM FOR THEIR CONSISTENT STRENGTH AND CONVICTION. ”

WILLIAM C. AGEE, PAUL BURLIN: THE LAST PAINTINGS, THE PASADENA ART MUSEUM, 1971

OIL ON CANVAS

63 3/4” X 46 1/8”

SIGNED LOWER RIGHT

OIL ON CANVAS

60” × 54”

SIGNED & DATED ‘63 LOWER LEFT

OIL ON CANVAS

48” X 72”

SIGNED LOWER RIGHT

1964

OIL ON CANVAS

72” X 48”

SIGNED & DATED ‘64

LOWER RIGHT

“

BURLIN, HOWEVER, THINKS AND ANGUISHES AND DISCOVERS: NO ONE PAINTS YOUNGER FOR HIS AGE THAN HE. IN HIS GRITTINESS AND UNPREDICTABILITY THERE IS A MORAL VALUE THAT IS ADMIRABLE. BEHIND IT, TOO, IS A POETRY WHICH WE HAVE TO FLUSH OUT FOR OURSELVES. HIS SPIRITUAL QUEST, IF THAT IS NOT TOO BLOODLESS AN EXPRESSION, IS VERY MUCH IN PROGRESS, AND WE CAN BY NO MEANS FEEL FINISHED WITH HIS ART. IT IS SIMPLY TOO INVIGORATING.

OIL ON CANVAS

54” X 60”

SIGNED & DATED LOWER RIGHT

OIL ON CANVAS

48” X 72”

SIGNED LOWER RIGHT

“ I HAVE OFTEN BEEN ASKED WHAT IS MY PHILOSOPHY AS A PAINTER, AND WHAT PROPHECIES I CAN MAKE ABOUT THE FUTURE OF ART IN AMERICA. THE LATTER QUESTION I LEAVE TO THE MEN WITH THE LONG BEARDS, THE PONTIFICATORS, THE WISHFUL-THINKERS OF VARIOUS TYPES. AS TO MY PHILOSOPHY OF ART, I CAN ONLY SAY THAT I AM NOT A MAN WHO FELL ON A PATTERN AND REPEATED IT. CONTEMPORARY THOUGHT IS NOT A CONTEMPORARY THING. IT REFLECTS THE PASSION AND ASPIRATIONS OF A PEOPLE. THE ARTIST DEALS IN TERMS OF HIS OWN WITH IMAGES RELATED TO THIS CONTEMPORARY LIFE AND ASPIRATION. AND WHEN HE ENTERS THE DOMAIN OF PLASTIC ART IN ORDER TO EXPRESS THESE VALUES, HE IS SEEKING NEW IMAGES TO DIFFERENTIATE THEM FROM REALISM. WITHIN THIS APPROACH, THERE IS THE POSSIBILITY THAT THESE NEW IMAGES WILL HAVE A MAGIC OF THEIR OWN. ”

PAUL BURLIN

PAUL BURLIN

OIL ON CANVAS

72” × 78”

SIGNED & DATED ‘61 LOWER LEFT

OIL ON CANVAS

48” X 71 5/8”

SIGNED & DATED ‘59 LOWER RIGHT

OIL ON CANVAS

40” × 51”

SIGNED AT LOWER LEFT

“ THE THIRTIES WERE A POTPOURRI OF CHANGING REALITIES. AESTHETIC IDEAS IN AMERICA WERE DISTURBING SOUNDS, WITH MANY ECHOES. PAINTING LOOKED FOR A NEW MAGIC. ”

OIL ON CANVAS

60” X 54 1/2”

SIGNED & DATED LOWER RIGHT

OIL ON CANVAS

72” X 83”

SIGNED & DATED 1961 AT LOWER LEFT

“ WHILE SUCH LEADING MASTERS AS DE KOONING, ROTHKO AND GUSTON ARE TOTTERING ON THE EDGE OF BECOMING THE GRAND OLD MEN OF AMERICAN ART, MORE ATTENTION - PERHAPS TOO MUCH - IS NOW BEING GIVEN TO ITS EVER-YOUNGER LUMINARIES. IF HIS RETROSPECTIVE AT THE WHITNEY IS ANY INDICATION, HOWEVER, IT APPEARS THAT WE HAVE BEEN NEGLECTING ALL ALONG ONE OF OUR ELDER STATESMEN. IT HAS BEEN PAUL BURLIN’S FORTUNE NEVER TO HAVE GOT ENTANGLED WITH THE PHALANX OF IDEAS AND INTUITIONS THAT BECAME THE GESTURAL PAINTING OF THE NEW YORK SCHOOL. ”

OIL ON CANVAS

40” X 50”

SIGNED AT UPPER LEFT

MAX KOSLOFF, THE NATION, MARCH 10, 1962

“ THIS IS NOT TO SAY THAT SPONTANEITY PLUS SIGHTLESSNESS ARE THE ORTHODOX INGREDIENTS OF ART, BUT, IN THE CASE OF PAUL BURLIN, DEEP-STORED MEMORIES ERUPTED INTO A NEW KIND OF FREEDOM. IT WAS ALMOST AS IF THE VERY BURDEN OF HIS HANDICAP BECAME A LIBERATING FORCE. ”

KATHARINE KUH, APRIL, 1968

OIL ON CANVAS

32” X 45”

There are idea painters and there are those who think and feel the paint. What intrigues and engages me is to captivate the sensual within a pointed aesthetic-two contrary elements, one to excite, the other to cool..”

Paul Burlin

1886 BORN SEPTEMBER 10, IN NEW YORK, SON OF A GERMAN MOTHER AND ENGLISH FATHER. BROUGHT UP IN NEW YORK AND LONDON.

1900-1912 STUDIED PART TIME AT THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF ART AND THE ART STUDENT’S LEAGUE. ESSENTIALLY SELF-TAUGHT.

1903+ ILLUSTRATOR FOR THE DELINEATOR WHEN THEODORE DREISER WAS THE EDITOR.

1908-09 PROBABLE DATES OF EUROPEAN ART TOUR.

1910 FIRST TRIP TO SOUTHWEST. EXHIBITION IN NEW YORK OF SANTA FE WORKS. STRONG REVIEW FROM AUTHOR JAMES HUNEKER.

1911-13 STUDIO ON 10TH ST. NEW YORK. MURAL FOR MR. & MRS. EDWIN HARRIS.

1913 EXHIBITED IN THE ARMORY SHOW.

1914 MET NATALIE CURTIS, MUSICIAN AND ETHNOLOGIST. MARRIED 1917. (DIED 1921, PARIS).

1913-20 LIVED IN SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO. EXHIBITED IN THE DANIEL AND ANDERSON GALLERIES, NEW YORK.

1919 EXHIBITED AT THE PHILADELPHIA ACADEMY OF FINE ARTS. SHOW PRODUCED A CRITICAL BACKLASH THAT LED TO THE BURLIN'S EXODUS FROM AMERICA.

1921-32 LIVED, WORKED, AND EXHIBITED IN PARIS, FRANCE. OTHER EXHIBITS IN EUROPE AND NEW YORK. TRAVELED IN ENGLAND, BELGIUM, HOLLAND, GERMANY, SPAIN, AND NORTH AFRICA.

1922 MARRIED MARGARETE (MARGOT) KOOP, IN PARIS. (DIVORCED 1936). ONE DAUGHTER, BARBARA, NOW MARRIED TO EUGENE WEDELL, LIVES IN CALIFORNIA.

1930 INCLUDED IN THE NY MUSEUM OF MODERN ART’S 9TH EXHIBITION.

1932 RETURNED TO THE UNITED STATES. LIVED AND WORKED IN NEW YORK AND PROVINCETOWN, MASS. MEMBER OF THE FEDERAL PROJECT ORGANIZED BY THE WHITNEY MUSEUM. LEFT PROJECT IN 1936-37.

1937 MARRIED HELEN SIMONSON. (DIVORCED 1946). BOUGHT SUMMER HOME AND BUILT STUDIO IN WOODSTOCK, N.Y.

1944 EXHIBITED IN THE ART IN PROGRESS SHOW AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK.

1945 WON FIRST PRIZE OF $2,500 IN THE "PORTRAIT OF AMERICA" COMPETITION SPONSORED BY THE PEPSI-COLA COMPANY AND THE ARTISTS FOR VICTORY, INC. FOR THE SODA JERKER.

1947 MARRIED MARGARET TIMMERMAN FROM BATESBURG, SOUTH

1949 VISITING ARTIST AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA, (SUMMER).

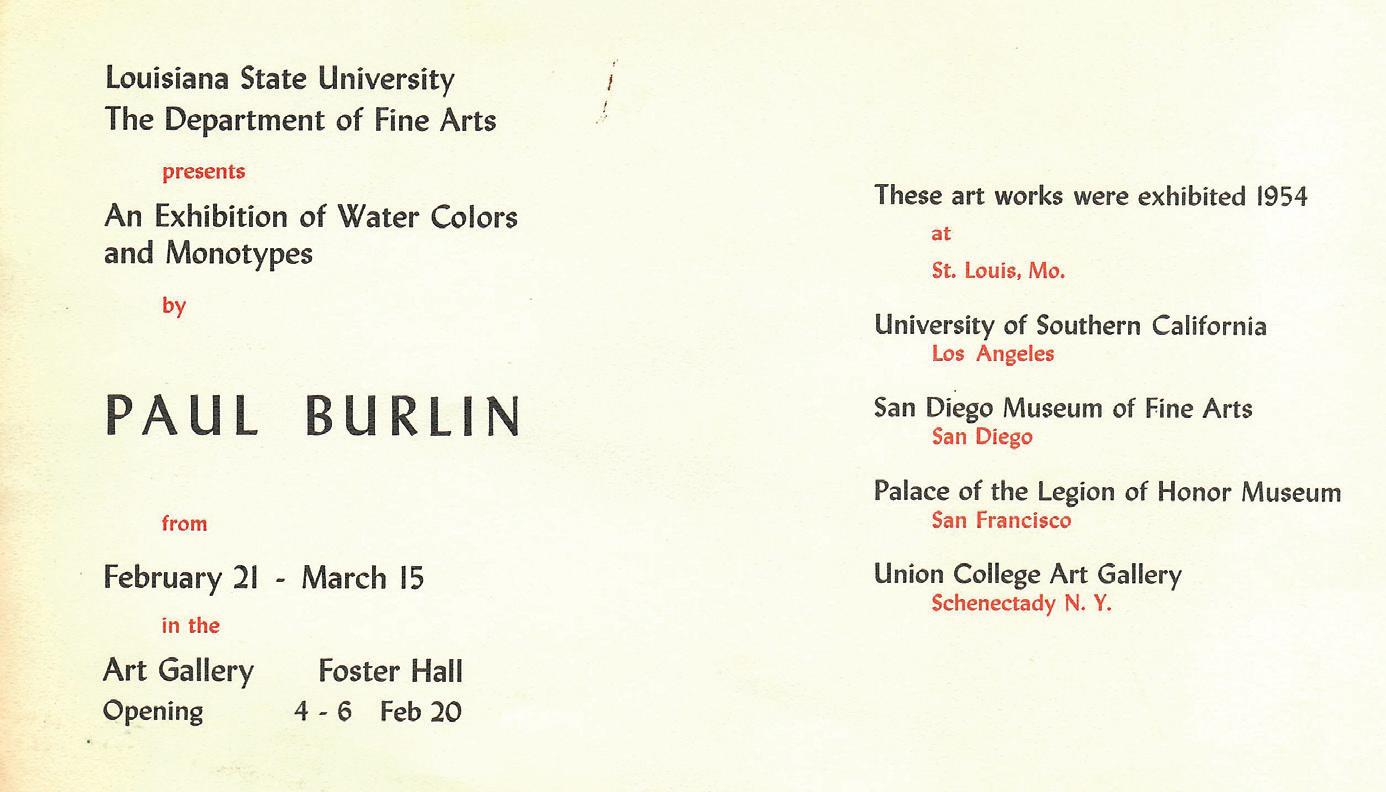

1949-54 ARTIST IN RESIDENCE AT WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY, ST. LOUIS.

1951 VISITING ARTIST AT THE UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO (SUMMER).

1952 VISITING ARTIST AT THE UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING (SUMMER).

1954 VISITING ARTIST AT THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA, LOS ANGELES (SUMMER).

1954-55 JOHN HAY WHITNEY FOUNDATION VISITING PROFESSOR AT UNION COLLEGE, SCHENECTADY, NEW YORK.

1959 FIRST OF EIGHT CORNEA TRANSPLANTS.

1959 ONE OF THREE FIRST PRIZEWINNERS OF $1,000, ART U.S.A.: 59, NEW YORK, FOR ROSE, WHITE, UPRIGHT.

1959-60 CORCORAN 28TH BIENNIAL EXHIBITION.

1960 VISITING ARTIST IN RESIDENCE, SCHOOL OF THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO. WON HONORARY WATSON F. BLAIR AWARD OF $2,000 FOR IT IS, ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO.

1960 REVISITED LONDON AND PARIS AND TRAVELED THROUGHOUT SPAIN.

1961 LIVED IN NEW YORK; SUMMER IN PROVINCETOWN, MASSACHUSETTS. WORK HANDLED BY GALLERY MEYER, NEW YORK CITY.

1962 RETROSPECTIVE EXHIBITION, THE AMERICAN FEDERATION OF ARTS. EXHIBITIONS IN PHILADELPHIA ART ALLIANCE, THE WHITNEY MUSEUM IN NEW YORK AND BOSTON COLLEGE GALLERY (1964). MONOGRAPH BY IRVING SANDLER.

1962-96 WORK HANDLED BY BORGENICHT GALLERY.

1963 PAFA, J. HENRY SCHIEDT MEMORIAL PRIZE.

1963-4 ARTIST IN RESIDENCE, UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS.

1968 PENNSYLVANIA ACADEMY OF FINE ARTS EXHIBITION. WON $2,000 FIRST PRIZE FOR RED, RED, NOT THE SAME LL.

1969 DIED, MARCH 13, N.Y.C. BURIED IN SOUTH CAROLINA.

1971-72 EXHIBITION OF SERIES OF NINE AT THE MOMA, NEW YORK AND THE PASADENA ART MUSEUM, PASADENA, CALIFORNIA.

1976 MARGARET BURLIN DIED, SEPT. 6, COLUMBIA, S.C.

1911 UNNAMED GALLERY IN UPTOWN NEW YORK.

1913, 1914-20 DANIEL GALLERY, NEW YORK.

1926, 27 KRAUSHAAR ART GALLERIES, NEW YORK..

1927 WESTHEIM GALLERY, BERLIN.

1928 DE HAUKE GALLERY, NEW YORK

1942, 43, 44 ASSOCIATED AMERICAN ARTISTS, NEW YORK.

1944 VINCENT PRICE GALLERY, LOS ANGELES.

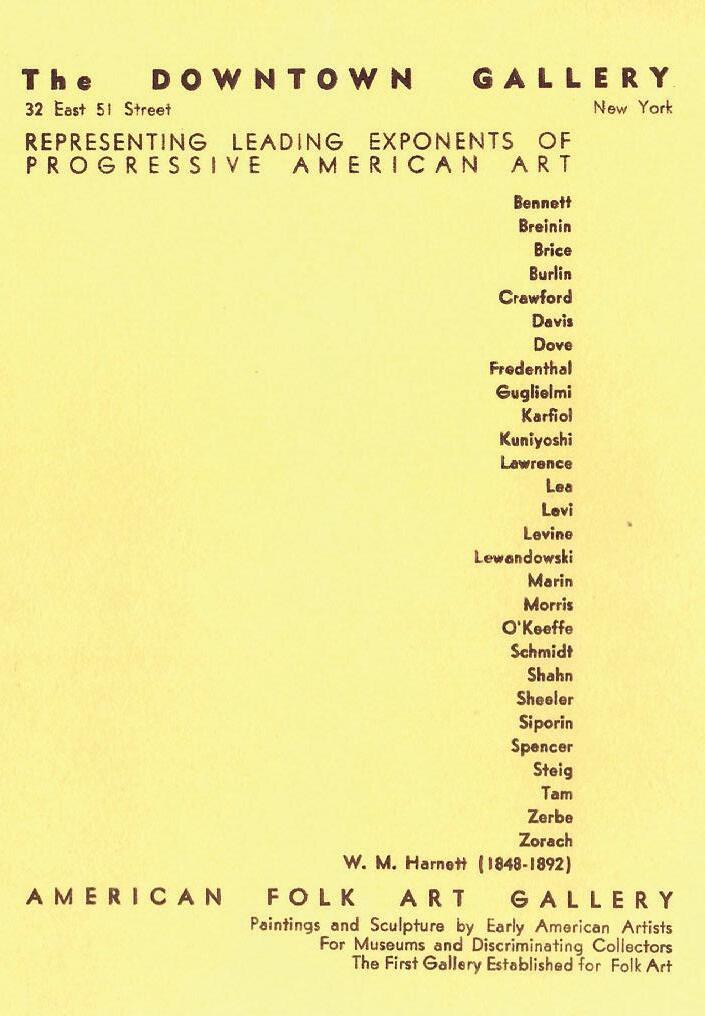

1946, 49, 52, 53

DOWNTOWN GALLERY, NEW YORK

1949 UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA, ST PAUL.

1950 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN ILLINOIS.

1952 UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING.

1954 WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY, ST. LOUIS. UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA, LOS ANGELES. THE FINE ARTS GALLERY, SAN DIEGO.

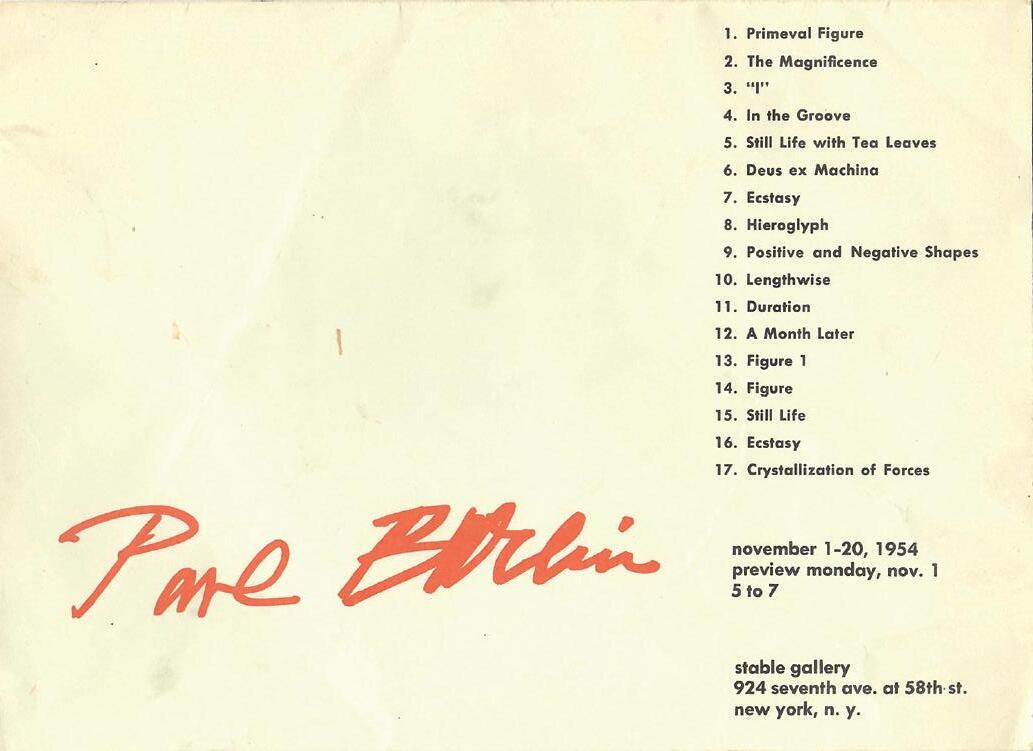

1954 MARTIN SCHWEIG GALLERY OF MODERN ART, ST. LOUIS. UNION COLLEGE GALLERY SCHENECTADY, N. Y. LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY GALLERY, BATON ROUGE, LO. THE STABLE GALLERY, NEW YORK

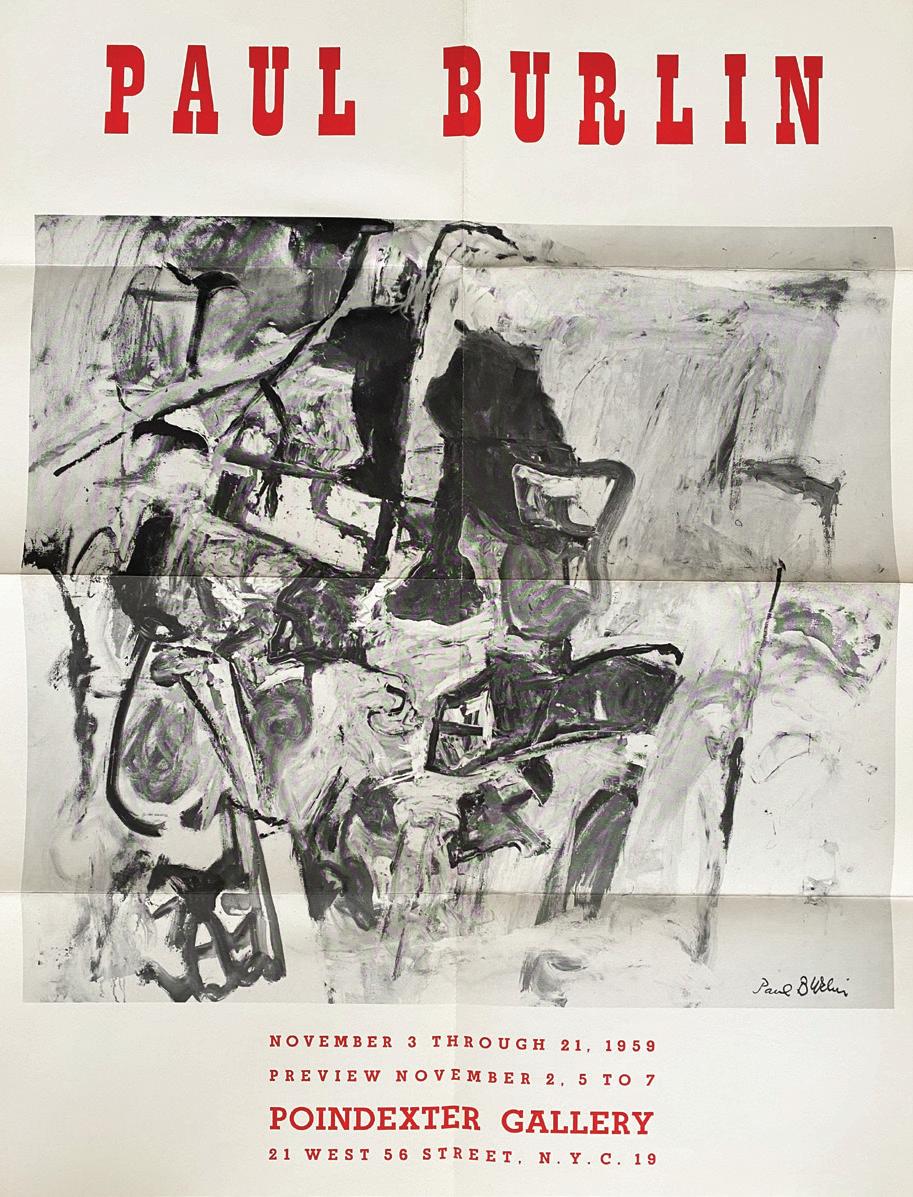

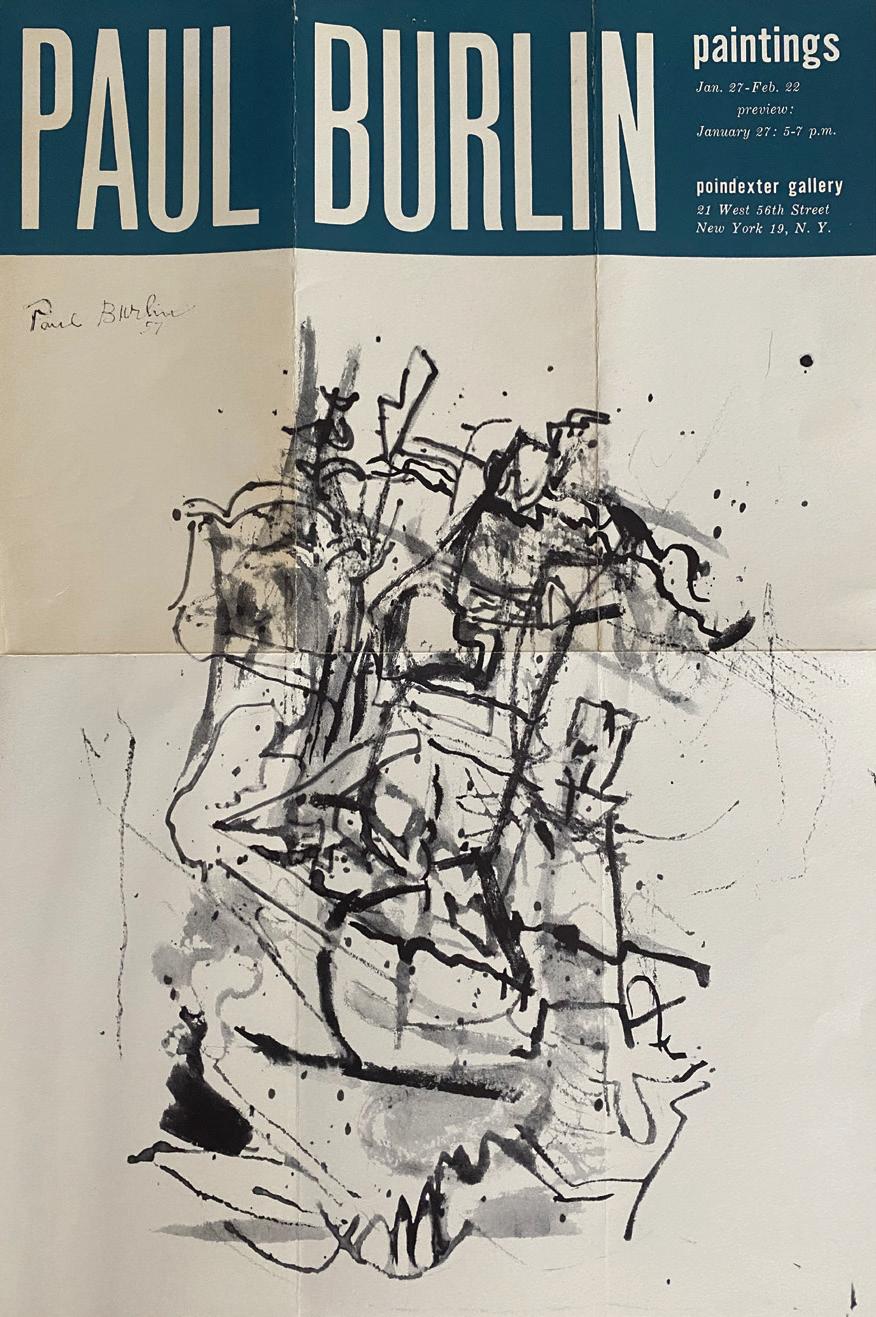

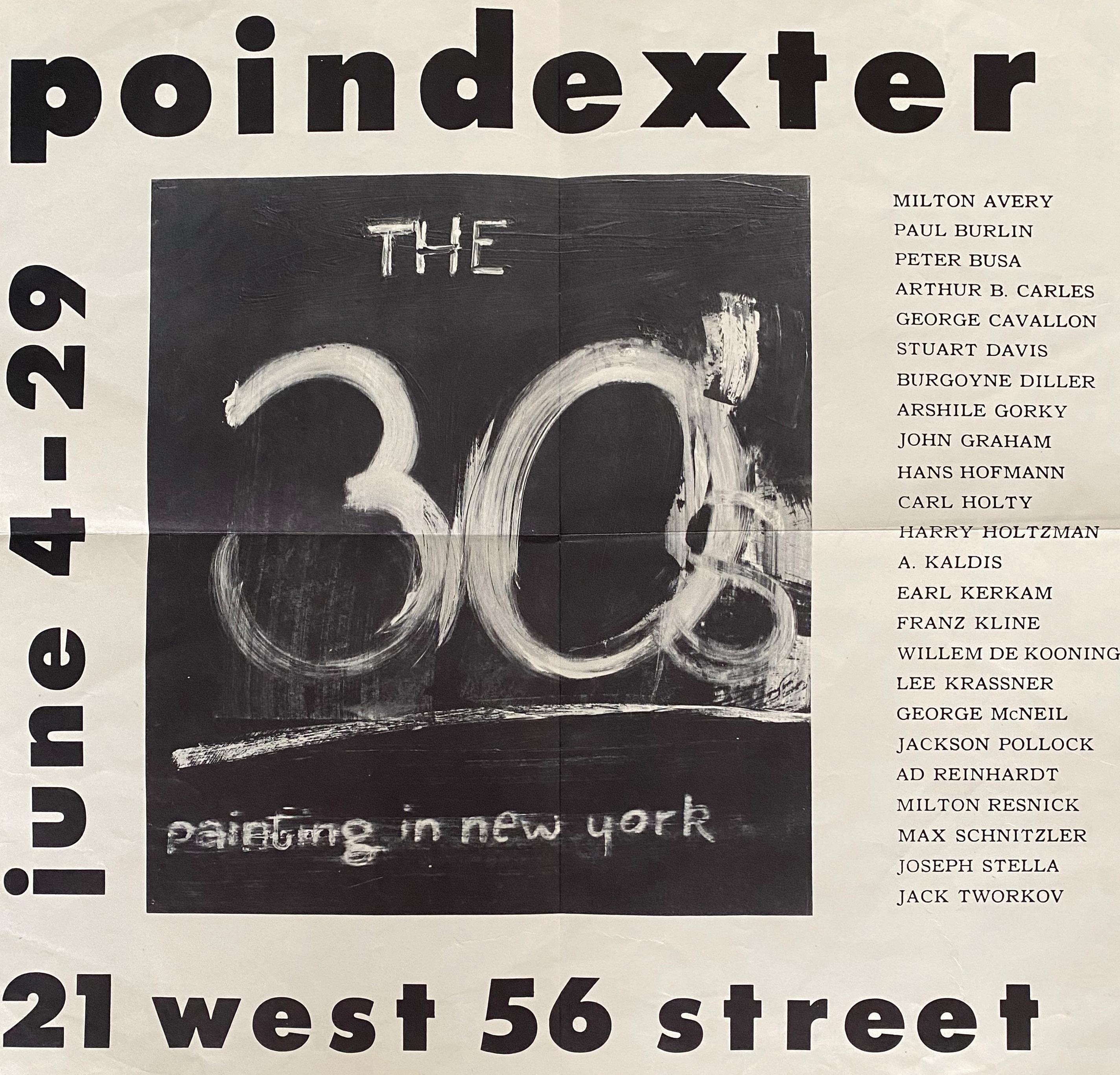

1958, 59, 62 POINDEXTER GALLERY, NEW YORK.

1959 UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI. STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, NEW PALTZ, N.Y. ALAN GALLERY, NEW YORK.

1960 THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO. SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY. HOLLAND GOLDOWSKY GALLERY, CHICAGO.

1962-64 RETROSPECTIVE EXHIBITION SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN FEDERATION OF ARTS FIRST SHOWN AT THE PHILADELPHIA ART ALLIANCE, FOLLOWED BY THE WHITNEY MUSEUM, NEW YORK AND THEN AT THE BOSTON COLLEGE GALLERY TWO YEARS LATER.

1962 POINDEXTER GALLERY, NEW YORK. GALLERY MAYER, NEW YORK.

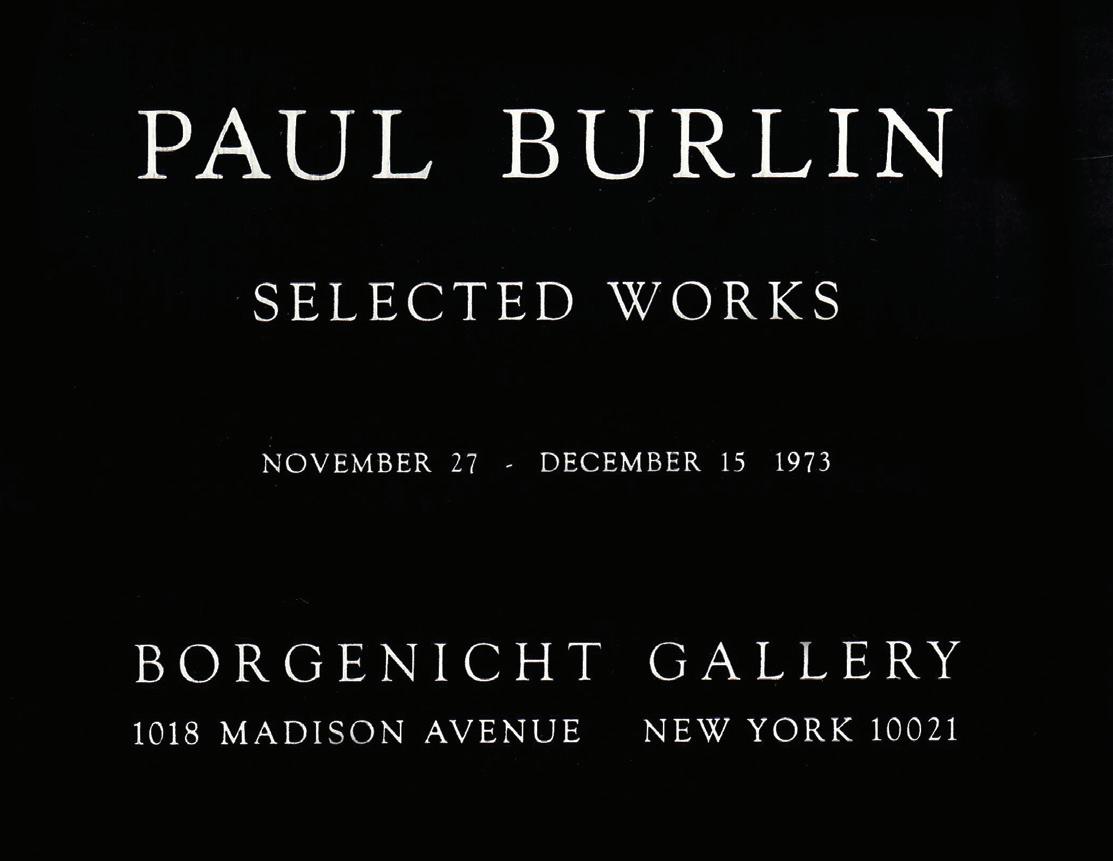

1963-66, 70, GRACE BORGENICHT GALLERY, NEW YORK. 71, 73, 75, 81, 86, 87

1964 UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS, AUSTIN. HILLWOOD GALLERY, GREENVILLE, N.Y.

1970 SERIES OF NINE RETROSPECTIVE AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK WITH A PARALLEL EXHIBITION AT THE GRACE BORGENICHT GALLERV. NY.

1913 THE ARMORY SHOW, 67TH STREET ARMORY, NEW YORK.

1916 ANDERSON GALLERIES, NEW YORK. INDEPENDENTS SHOW.

1917 PALACE OF THE GOVERNORS, SANTA FE.

1919 PENNSYLVANIA ACADEMY OF FINE ART, PHILADELPHIA.

1919-24 VENICE INTERNATIONAL, VENICE, ITALY. COPENHAGEN, DENMARK. LONDON, ENGLAND, TRI-NATIONAL EXHIBITION. LONDON, ENGLAND, GRAFTON GALLERIES. PARIS, GALLERIES GEORGES PETIT. (EXACT DATES UNKNOWN)

1922 SANTA FE MUSEUM OF FINE ART, SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO.

1921-24 SALON DES INDEPENDENTS, PARIS, FRANCE.

1930 NEW YORK MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK.

1935 ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO.

1938 WOODSTOCK GALLERY, N.Y. WOODSTOCK ANNUAL EXHIBITION.

1939 WORLD’S FAIR, NEW YORK.

1941 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF DESIGN, NEW YORK. 121ST EXHIBITION.

1944 MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK. ART IN PROGRESS EXHIBITION.

1945 BOSTON, MASS. MODERN ART EXHIBITION.

1946 DOWNTOWN GALLERY, NEW YORK. ANNUAL EXHIBITION. WHITNEY MUSEUM, NEW YORK. 21ST ANNUAL EXHIBITION OF CONTEMPORARY PAINTING. CARNEGIE INSTITUTE. PITTSBURGH, PENNSYLVANIA. WMAA ANNUALS. MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK. 40 LIVING AMERICANS. SMITHSONIAN MUSEUM, WASHINGTON, D.C., METROPOLITAN MUSEUM, NEW YORK, GALLERIES IN PRAGUE AND PARIS. ADVANCING AMERICAN ART.

1949 DOWNTOWN GALLERY, NEW YORK. THE ARTIST SPEAKS. WHITNEY MUSEUM, NEW YORK. JULIANA FORCE AND AMERICAN ART: MEMORIAL EXHIBITION. UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA, MINNEAPOLIS.

1950 THE ALAN GALLERY, NEW YORK. WHITNEY MUSEUM, NEW YORK, 7950 ANNUAL OF CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN PAINTING.

1952 WHITNEY MUSEUM, NEW YORK. FROM THE EDITH AND MILTON LOWENTHAL COLLECTION. POINDEXTER GALLERY, N.Y. METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, NEW YORK. AMERICAN WATER COLORS, DRAWINGS AND PRINTS, 1952

1954 WALKER ART CENTER, MINNEAPOLIS, MINN. FOURTH BIANNUAL OF PAINTINGS AND PRINTS. PALACE OF THE LEGION OF HONOR, SAN FRANCISCO.

1957 MUSEÉ GALLERIE, PARIS. PEINTRES AMÉRICAINS CONTEMPORAINS.

1958 WHITNEY MUSEUM, NEW YORK. FRIENDS. POINDEXTER GALLERY, NEW YORK.

1959 NEW YORK COLISEUM, NEW YORK. ART USA, 1959. BURLIN’S UNTITLED SELF-PORTRAIT WON FIRST PRIZE. THE PAINTING TRAVELED TO AN EXHIBITION IN ROME, ITALY.

1959 CAMINO GALLERY, NEW YORK. FIVE CONTEMPORARY PAINTERS IN A 25TH YEAR RETROSPECTIVE.

1959- 60 CORCORAN GALLERY, NEW YORK. 28TH BIANNUAL EXHIBITION.

1962 BROOKS MEMORIAL ART GALLERY, MEMPHIS, TENN. CINCINNATI ART MUSEUM, OHIO.

1964 CINCINNATI ART MUSEUM, OHIO.

1965 THE BUTLER INSTITUTE OF AMERICAN ART, YOUNGSTOWN, OHIO. THE ANNUAL MID-YEAR SHOW.

1966 WHITNEY MUSEUM, NEW YORK. CONTEMPORARY PAINTINGS.

1967 WITHERSPOON ART GALLERY, UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, GREENSBURO. ART ON PAPER INTERNATIONAL.

1977 EMERSON MUSEUM OF ART, PROVINCETOWN, MASS

1979 THE CONTEMPORARY ARTS CENTER, CINCINNATI, OHIO.

1968 UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS, AUSTIN. PENNSYLVANIA ACADEMY OF FINE ART, PHILADELPHIA.

1980 SMITHSONIAN MUSEUM, WASHINGTON, D.C. PIONEERS OF AMERICAN ART REVIEW.

1981 THE BROOKLYN MUSEUM, NEW YORK. EDITH AND MILTON LOWENTHAL COLLECTION.

1987 GERALD PETERS GALLERY, SANTA FE. SANTA FE ART COLONY.

1988 GRACE BORGENICHT GALLERY, NEW YORK, SIX ABSTRACT PAINTERS.

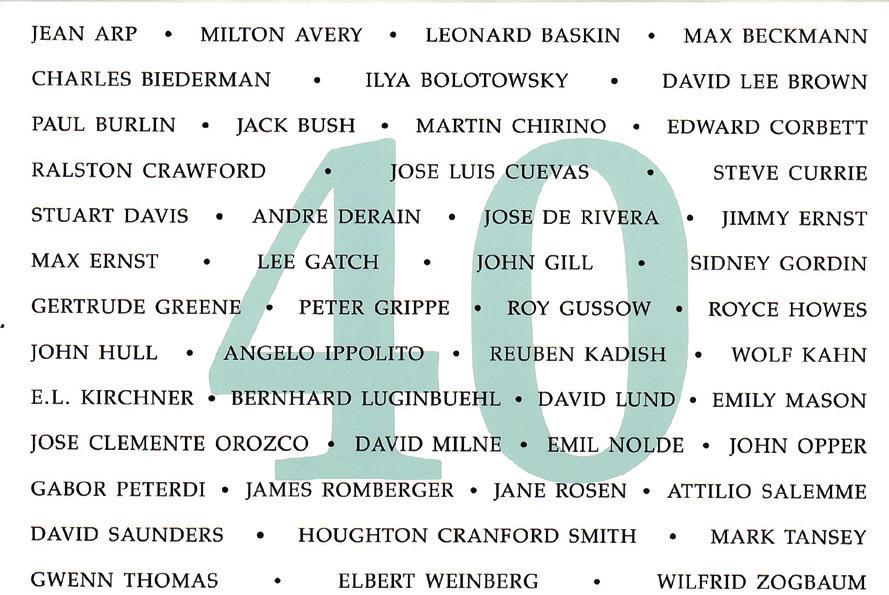

1991 GRACE BORGENICHT GALLERY, NEW YORK. FORTY EXHIBITION YEARS, MAY 1951 TO MAY 1991.

1993 LEWIS NEWMAN GALLERIES, LOS ANGELES. VISIONS IL.

1995 GALLERIE RAAB, BURLIN, GERMANY.

1996-97 METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, NEW YORK. EDITH AND MILTON LOWENTHAL COLLECTION.

WRITINGS BY BURLIN

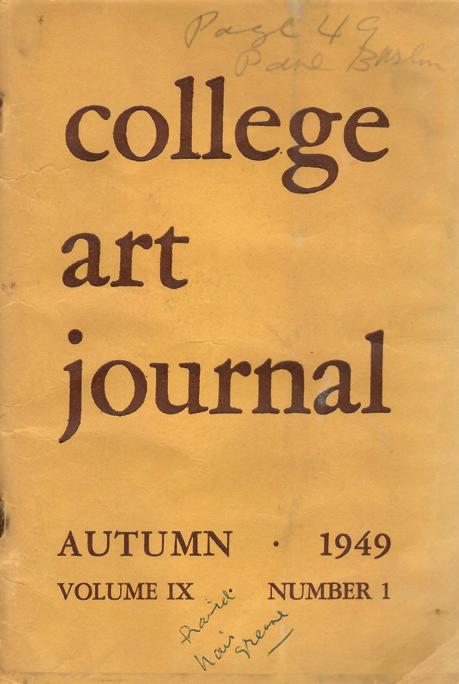

THE ARTIST’S POINT OF VIEW. COLLEGE ART JOURNAL 9:49-51, 1949. THE ARTIST AS TEACHER. COLLEGE ART JOURNAL 9:265-7, 1950.

ADDRESSES

1. ON AMATEURISM.

2. ONTHE TEACHING OF PAINTING, PERSPECTIVES (WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY, ST. LOUIS) SPRING, 1954. 4 ILLUSTRATIONS.

BOOKS

CHIL ARNOLSON LES ARTISTS AMERICAINES MODERNES DE PARIS, LE TRIANGLE, PARIS 1932, 3 ILLUSTRATIONS.

VAN DEREN COKE, TAOS AND SANTA FE, THE ARTIST’S ENVIRONMENT, 1882 TO 1942, 1963, P 27, 31-35 + 9 OTHER PAGES.

GANAUER, EMILY: BEOSF TART , 1948, P 151.

KOOTZ, SAMUEL: NEW FRONTIERS IN AMERICAN PAINTING, 1943, P 55.

MYERS, BERNARD: MODERN ART IN THE MAKING, 1950, P 391.

NORDNESS, LEE, EDITOR, ART U.S.A. NOW, VOLUME |. J. BUCHNER, LTD. LUCERNE, SWITZERLAND, 1962, P 30-34, 4 ILLUSTRATIONS.

PEARSON, RALPH: EXPERIENCING AMERICAN PICTURES, 1943, P 175-181.

PEARSON, RALPH: THE MODERN RENAISSANCE IN AMERICAN ART, HARPER BROS. 1954.

IRVING SANDLER, PAUL BURLIN, AMERICAN FEDERATION OF ART, 1962.

GEORGE P. TOMKO, CATALOG OF THE ROLAND P. MURDOCK COLLECTION, WICHITA ART MUSEUM, 1972. P. 24.

SHARYN ROHLFSEN UDALL, MODERNIST PAINTING IN NEW MEXICO, 1913 TO 1935, UNIVERSITY OF NEW MEXICO PRESS, 1984. “EARLY ARRIVALS; FAUVE-EXPRESSIONIST TRADITION, SECTION 2”

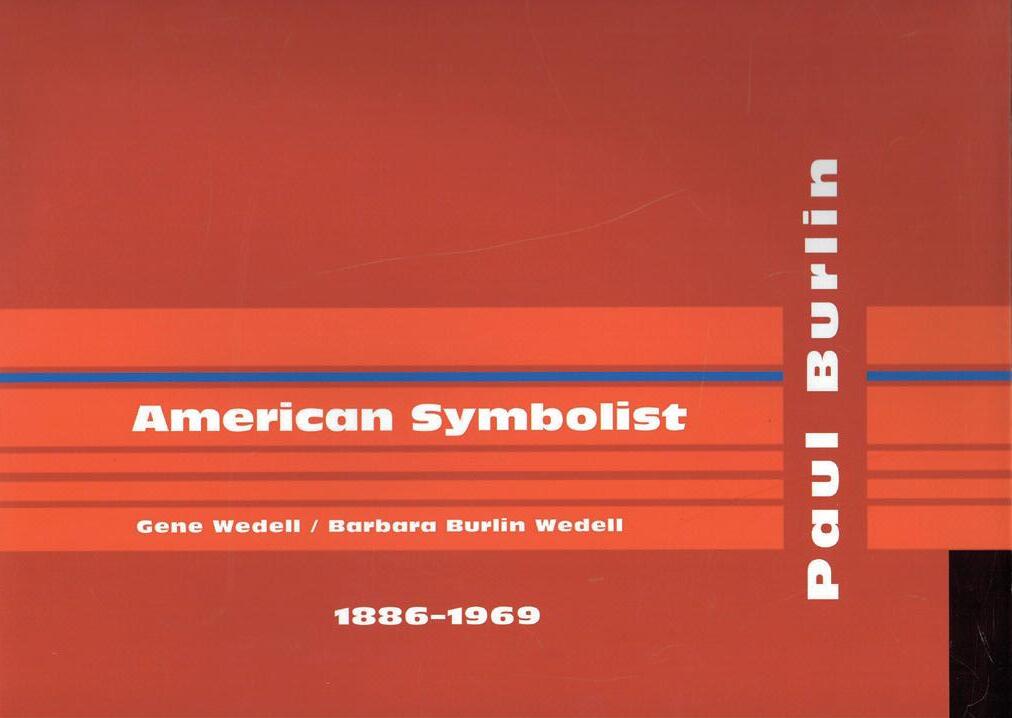

WEDELL, GENE AND BARBARA BURLIN WEDELL, PAUL BURLIN, AMERICAN SYMBOLIST, 2009, PAUL BURLIN ART TRUST.

WEDELL, GENE AND BARBARA BURLIN WEDELL, PAUL BURLIN CATALOG, ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONIST PERIOD, 1946-1958, 2009, PAUL BURLIN ART TRUST.

ARTISTS’ ARCHIVES

DOROTHY SECKLER, PAUL BURLIN, 1962, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTE. TAPED INTERVIEWS.

WILL BARNET ON PAUL BURLIN, INTERVIEW FOR THE SMITHSONIAN ARTIST’S ARCHIVES, 1966.

PERIODICALS

AMERICAN ARTISTS AT PARIS. FORMES (PARIS—PHILADELPHIA), 22:225-227 F 1932.1 ILLUSTRATION.

ART U.S.A., 1962, 1 ILLUSTRATION.

ATIRNOMIS: ARTS, DEC. 1971, P 64.

BRACE, ERNIST: WOODSTOCK ANNUAL. MAGAZINE OF ART 31:536 A 1938, 1 ILLUSTRATION.

CHEW, PAUL A. : PAUL BURLIN. PERSPECTIVES (WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY, ST. LOUIS) SPRING 1954.

CLEMENTS, G. :EXHIBITION, BEVERLY HILLS. ARTS AND ARCHITECTURE

61:14 MARCH 1944.

DOCUMENT: ON AMATEURISM. ARTS DIGEST 29:14 DEC. 15, 1954. PORTRAIT.

DREISS, JOSEPH: ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM. ARTS MAGAZINE SEPT. 1975, P 26.

EXHIBITION OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF PAINTERS, SCULPTORS, AND GRAVERS. CREATIVE ART 10:133 FEBRUARY 1932, 1 ILLUSTRATION.

HLF. : EXHIBITION, DOWNTOWN GALLERY. ART NEWS 48:49 APRIL 1949, 90 90

FARBER, MANNY: EXHIBITION, ASSOCIATED AMERICAN ARTISTS GALLERY. MAGAZINE OF ART 36:109 MARCH 1943, 1 ILLUSTRATION.

FIELD, HAMILTON EASTER: DECORATIONS BY BURLIN IN RESIDENCE OF GEORGE A. HARRIS. ARTS 1:30-31 FEB-MARCH 1921. | ILLUSTRATION

S.G.: EXHIBITION AT POINDEXTER GALLERY. ARTS 32:53 FEB. 1959. 1 ILLUSTRATION.

GOODRICH, LLOYD: NEW YORK EXHIBITIONS. ARTS 15:124 FEB. 1929. 1 ILLUSTRATION.

B.DH. : RECENT DRAWINGS AT ALAN. ARTS 33-65 JAN. 1959. HARITT, FREDERICK: DIE NEUEREN WERKE VON PAUL BURLIN. WERK (ZURICH) 39:27-32 JAN. 1952.

HEWETT, EDGAR L.: OPENING OF THE ART GALLERIES IN SANTA FE. ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY 7:66 JAN-FEB. 1918. 1 ILLUSTRATION.

MAX KOZLOFF, REPRINTED FROM THE NATION, MARCH 10, 1962, BY ART INTERNATIONAL P 45, VI/3, APRIL, 1962.

MYERS, BERNARD: THE PAINTING OF PAUL BURLIN, PERSPECTIVES (WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY, ST. LOUIS) SPRING, 1954.

FP. : ABSTRACTIONS AT DOWNTOWN GALLERY. ART NEWS 52:37 MARCH 1953.

PEARSON, RALPH: BURLIN—PIONEER AMERICAN MODERN. FORUM P 37:367 JUNE 1938.

PEMBERTON, MURDOCK: EXHIBITION AT DEHAUKE GALLERIES. CREATIVE ART 4:52-54 FEB. 1929. 1 ILLUSTRATION.

PRIZE WINNERS-THE BIG SHOWS. AMERICAN ARTIST 10:16 JAN. 1946 1 ILLUSTRATION.

REVIEWS AND PREVIEWS. ART NEWS 45:54 APRIL 1946. 1 ILLUSTRATION.

IH.S. : ARMORY SHOW VETERAN AT ALAN GALLERY. ART NEWS 57:11 FEBRUARY 1958.

RECENT CANVASES AT POINDEXTER. ART NEWS 56:11 FEB. 1958.

SCHULZE, FRANZ: ART NEWS FROM CHICAGO. ART NEWS 59:46 MAY 1960.

SCHNAKENBERG, H.E. : NEW YORK EXHIBITIONS. ARTS 7:173, 174. MARCH 1925. 2 ILLUSTRATIONS.

SCHUYLER, JAMES: PAUL BURLIN’S LAST PAINTINGS, ART NEWS P 28-29 DEC. 1970. PORTRAIT, 1 ILLUSTRATION.

SECKLER, DOROTHY GEES: PROBLEMS OF PORTRAITURE. ART IN AMERICA 46:35 WINTER 1958. STATEMENT CHAIN OF GENERATIONS; CONTRAST AND CONTINUITY. ART IN AMERICA 48:97 SPRING 1960.

SUSAN SIVARD, THE STATE DEPARTMENT “ADVANCING AMERICAN ART EXHIBITION OF 1946 AND THE ADVANCE OF AMERICAN ART. ARTS MAGAZINE, P 92-99. APRIL 1984.

WALTER, PAUL A.F. : ART IN WAR SERVICE. ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY 7:398 NOV-DEC. 1918. 1 ILLUSTRATION.

WHITNEY, GEORGE,: ABRUPT ENDING: THE WORK OF PAUL BURLIN. ARTS, SEPT. 1981, P 97.

GRACE BORGENICHT GALLERY, NEW YORK. RECENT PAINTINGS, PAUL BURLIN 1963. PAUL BURLIN 1965. PAUL BURLIN LAST WORKS 1971. PAUL BURLIN LATE PAINTINGS, 1981.

CIBI-GEIGY ART COLLECTION, ACQUISITIONS AS OF SUMMER OF 1973, 1974, 2 ILLUSTRATIONS. ABSTRACTS OF ABSTRACTION, SEPT. 1981 P 15-16.

ENCYCLOPEDIA BRITANNICA, COLLECTION OF CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN PAINTING, 1945, 1 ILLUSTRATION.

GRAND CENTRAL ART GALLERIES, FROM |.B.M. COLLECTION, 60 AMERICANS SINCE 1800 NOV-DEC. 1946. SEND BY THE U.S. STATE DEPARTMENT TO CAIRO IN 1947.

MACDOWELL COLONY, SEVEN DECADES OF MACDOWELL ARTISTS, 1976, 1 ILLUSTRATION.

EDITH AND MILTON LOWENTHAL COLLECTION, BROOKLYN MUSEUM, MARCH 1981, P 9-11, 4 ILLUSTRATIONS.

METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART BULLETIN, SUMMER 1996, P 19, 42, SELECTED WORKS FROM THE EDITH AND MILTON LOWENTHAL COLLECTION. 1 ILLUSTRATION.

NATIONAL BANK OF TULSA ART COLLECTION + THE WILLIAMS COMPANIES, 1968, 3 ILLUSTRATIONS.

NEBRASKA ART ASSOCIATION, SIXTY-SECOND ANNUAL EXHIBITION, 1972. NEW YORK MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, PAINTING AND SCULPTURE IN MOMA, 1948, P 234, 1 ILLUSTRATION. ART IN PROGRESS-15TH ANNUAL EXHIBITION, 1941, P 62, 219, 1 ILLUSTRATION. PAUL BURLIN (1886-1969) LATE PAINTINGS. DEC-JAN. 1970-71.

PASADENA ART MUSEUM, PAUL BURLIN THE LAST PAINTINGS SEPT-NOV. 1971.

UNIVERSITY OF LOWA, CONTEMPORARY, 1958, 1 ILLUSTRATION. ART MUSEUM, UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS, RECENT AMERICAN PAINTINGS, 1964, 1 ILLUSTRATION. PAINTING AS PAINTING, FEB. 1968 P 28.

WHITNEY MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART CATALOG, THE COLLECTION, 1914-1960.

ANSCHUTZ COLLECTION, DENVER, COLORADO.

AUBURN UNIVERSITY, AUBURN, ALABAMA.

BUTLER INSTITUTE OF AMERICAN ART, YOUNGSTOWN, OHIO.

BROOKLYN MUSEUM, BROOKLYN, NEW YORK.

CARNEGIE MUSEUM OF ART, PITTSBURGH, PENN.

CARLETON COLLEGE, NORTHFIELD, MINNESOTA

CIBA GEIGY COLLECTION.

COLUMBIA MUSEUM OF ART, COLUMBIA, SOUTH CAROLINA.

ENCYCLOPEDIA BRITANNICA.

INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS MACHINES CORPORATION.

JOHNSON & SON, INC.

LAMONT ART GALLERY, PHILLIPS EXETER ACADEMY.

MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK.

MODERN MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART.

NEWARK MUSEUM, NEWARK, N.J.

ROSE ART MUSEUM, BRANDEIS, UNIVERSITY, WALTHAM, MASS.

CIBA GEIGY COLLECTION

SAN FRANCISCO MUSEUM OF MODERN ART. SAN FRANCISCO, CALIF.

MR. & MRS. WM. EISNER COLLECTION

SANTA FE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, SANTA FE, N.M.

FEIBES & SCHMITT COLLECTION

SHELDON MEMORIAL ART GALLERY, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA, LINCOLN.

MR. & MRS. SAM JAFFEE COLLECTION

EDWIN HARRIS COLLECTION

SIDNEY KOHL COLLECTION

THE MILTON LOWENTHAL COLLECTION

VINCENT PRICE COLLECTION

NATHANIAL SALTONSTALL ARTS FUND

DR. & MRS. SAMUEL SUSSMAN COLLECTION

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTE, GIFT OF S.C.

UNIVERSITY OF NEW MEXICO, ALBUQUERQUE, N.M.

TEL-AVIV MUSEUM, ISRAEL.

UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA, MINNEAPOLIS, MINNESOTA.

SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY, CARBONDALE, ILLINOIS.

WADSWORTH ATHENIUM, HARTFORD, CONN.

WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY, ST. LOUIS.

WHITNEY MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART, NEW YORK.

WICHITA ART MUSEUM, THE ROLAND P. MURDOCK COLLECTION, WICHITA, KANSAS.