14 minute read

History of the Graphic stresses responsibility of student journalists

History of the Graphic stresses responsibility of student journalists to the community

EMILY SHAW | PIXEL EDITOR

Although the Graphic newsroom in the Center for Communication and Business building lies mostly empty, the space holds a long, meaningful history of students dedicated to providing news for their community.

Former editors, a former adviser and a current adviser of the Graphic share the challenges and accomplishments they experienced; they discuss Pepperdine’s history of student publications, the relationship between the paper and its audience and journalistic principles, providing a glimpse into the inner workings of the student news organization.

“It’s a lab in the sense that it’s OK to make mistakes, and you have kind of this umbrella of protection, so you’re not totally just jumping into something scary unprotected,” Pepperdine and Graphic alumna Falon Barton (2015) said. “But at the same time, it’s a real job with real tangible consequences with real tangible results.”

The Birth of the Graphic

On Oct. 30, 1937, the “GraPhiC” — reflecting the initials of George Pepperdine College through its capitalization — published its first edition.

It listed three individuals as part of the staff: Editor Bobby King, Business Manager Mac B. Rochelle and Faculty Adviser Hugh M. Tiner.

The following bullet points are the objectives of the Graphic at the time of its first edition, which come directly from the Graphic’s first print issue: • To reflect in an unbiased manner the campus news and such outside news as appears especially related to the college. • To help anything that helps George Pepperdine College. • To give religion a prominent place in these columns. • To help build up college athletics and all other beneficial extra-curricular activities. • To encourage sound scholarship. • To help build school tradition. • To offer constructive criticism, and to give praise where due. • To represent what we believe to be the best standards in college journalism.

Students could obtain an annual subscription to their weekly campus news by mailing $1 to the Graphic.

The first issues contained a News section, editorial page and Sports section, including many stories about the college’s firsts such as a record of the college’s first week, the first weekly fellowship forum, the first track team and the first chorus and orchestra rehearsals.

“It is all-important that those who are here now shall realize that they make up the small stream that is shaping the course of the mighty river,” the Graphic staff wrote in its first edition. “It is so very important that each one here appreciate the part he must play in the molding of this school in its infancy.”

Other Student Publications on Campus

(previous page)

Photo Illustration by Ali Levens

Photos of Graphic students from various years appear behind the letters taken from old editions that make up the name of the student newspaper. The Graphic has been around for about 84 years since 1937, when George Pepperdine College began its first semester.

(left)

Photo Courtesy of Pepperdine Libraries Special Collections and University Archives

The front page of the Graphic’s first edition, published Oct. 1937, covers the launch of George Pepperdine College’s first semester. The Graphic is Pepperdine University’s oldest student organization and has evolved since then, while staying true to its original mission to inform the Pepperdine community.

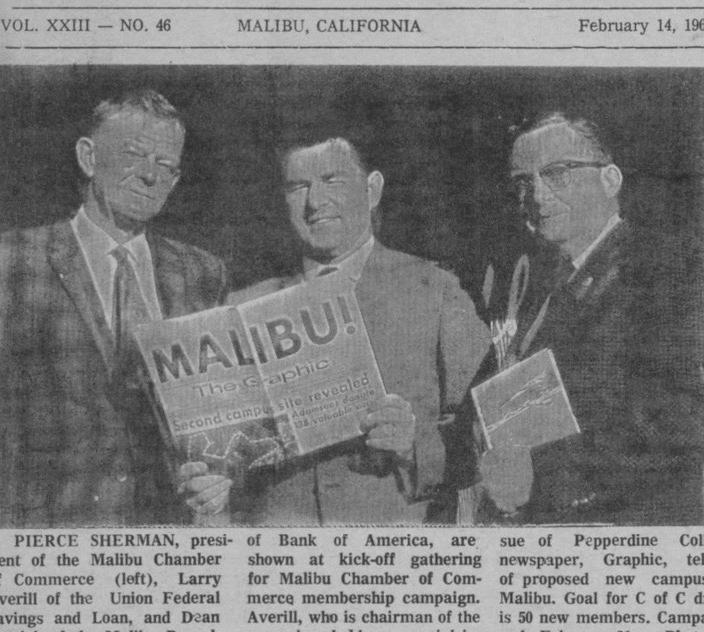

Photo Courtesy of The Malibu Times

In its 46th edition, published Feb. 14, 1969, The Malibu Times features a photo of Larry Averill of the Union Federal Savings and Loan holding a special issue of the Graphic, which tells of Pepperdine’s proposed new Malibu campus. The Graphic relocated to the Malibu campus in 1972, which prompted students in Los Angeles to form the Inner View. dine’s dominant news source on campus, other publications have appeared to serve different needs of the Pepperdine community over the years.

Due to an unknown conflict between the Graphic and the Association for Black Students during an ABS meeting in 1968, the Graphic suspended its Nov. 21 issue, which led some Black students to start their own newspaper, the Black Graphic. There are only three known publications of the Black Graphic.

In spring 1969, the Black Graphic wrote about Larry Kimmons’ death and the University’s response, the perspective of an Asian American student involved with the Black Graphic, the importance of teaching Black studies and the phenomenality of African American women, among many other topics. The Graphic also covered the death of Kimmons but not to the extent that the Black Graphic did.

In a 1969 newsletter, the Black Graphic wrote to Black Student Union members that they created the Black Graphic to amplify the voices of Black students.

“This media will serve the function of providing us Black Students with details of real happenings from the too real world..... [sic] as they relate to Black people,” the Black Graphic wrote. “This paper is not intended for those who are cowardly of heart, weak of mind, frail of body or sick of stomach. Although some of the material used in these pages may seem harsh, it is aimed at the liberation of the oppressed mind from the enemy — the racist pig.”

In 1972, Pepperdine opened the Malibu campus, and the Graphic relocated there. In the Graphic’s place, students remaining on Pepperdine’s LA campus started another student newspaper, the Inner View.

The Inner View, advised by Clint Wilson, provided news covering not just Pepperdine but also the surrounding LA community. While separate from the Graphic, the newspaper is a part of the history of Pepperdine student publications and supported the role of student journalists at the University.

The LA campus distinguished itself from the one in Malibu by embracing its urban location. In the first edition of the Inner View, the staff wrote an editorial titled “Urban newspaper” about the newspaper’s debut and the LA campus’ adoption of a new urban identity.

“The unveiling of the Inner View marks a new dimension for the fall at the Los Angeles Campus,” the Inner View staff wrote. “No longer will this campus be thought of as ‘the small, quiet campus on 79th St.’”

Covering the Surrounding Community

In 1972, the Inner View also interacted with the surrounding community, while focusing primarily on covering news affecting the LA campus.

After the Graphic moved to Malibu, Wilson said many of the juniors and seniors wanted to stay in Los Angeles and form the Inner View because of their pride in the LA campus and desire to cover the bustle of the city.

“They saw it as quite a journalistic challenge to cover the campus, as it was evolving in Los Angeles and in terms of working on covering the inner city,” Wilson said.

Wilson said he and others also revised the journalism curriculum and called it the Urban Journalism program, reporting on in-depth stories and taking on topics such as poverty and homelessness.

“The students really loved it,” Wilson said. “They just felt that it was a program that was preparing them for the real journalism world.”

During the Graphic’s 84-year history at Pepperdine, the paper and its connected publications have remained committed to serving the Pepperdine and surrounding communities.

While serving as reporter and editor of the Graphic, alumnus Tal Campbell (1961) also worked as an LAPD reporter at a newspaper in Los Angeles called Angeles Mesa News. Campbell said it was common for Graphic staff to work part-time for other local newspapers in the area.

Changing with the Times

Moving forward to 2012, Pepperdine and Graphic alumni Nate Barton (2016) and Falon Barton (2015) each joined the Graphic as first-year

students.

Now married, the Bartons said they both loved the community and sense of belonging they had at the Graphic. Falon Barton held multiple positions, including News editor, managing editor and Advertising director, and Nate Barton worked as creative director and executive editor, as well as other positions.

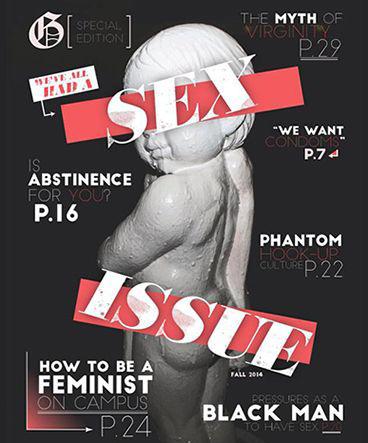

In 2014, the Graphic published its “Sex Issue” special edition. Special editions are issues of the Graphic that feature in-depth reporting on a topic or theme relevant to the community. This 2014 edition tackled a rather controversial topic, especially at Pepperdine — sex.

The Graphic staff had many thoughtful debates and conversations about the sex edition when putting it together, Falon Barton said, as she was managing editor at the time of the edition’s publication.

“One of our really good friends used the sex edition of the Graphic to come out as gay, and that was a big moment,” Nate Barton said. “It was really an honor to be a part of that.”

Elizabeth Smith, Journalism professor, Pepperdine Graphic Media director and faculty adviser to the Graphic, said the “Sex Issue” reflected a sentiment that things were changing socially on Pepperdine’s campus, especially with a bigger, more vocal push for an official LGBTQ+ student club.

Despite the controversial nature of the topic, Falon Barton said they did not receive any harsh or negative feedback.

Another major change for the Graphic was the shift to a digital-first model in the 2010s. “Digital first” is the idea of publishing content online first and then moving some of the stories into print editions.

Smith said the transition was two-fold: wanting students to get a more professional newsroom experience and wanting to better serve the audience by making content accessible online in a timely manner.

“Part of the reason why we do ‘digital first’ was because that’s where the industry was going,” Nate Barton said. “We’re trying to train the next generation of journalists.”

Falon Barton said becoming digital first also helped streamline things to be more efficient.

Today, a sign that reads “digital first, story first, audience first” sits in the trophy case in the Graphic newsroom.

Part of Pepperdine, Not Run by Pepperdine

Although the Graphic is a news organization at Pepperdine and is not financially independent, it is student-run and editorially independent from the University.

While Campbell was editor of the Graphic, the organization was self-supporting through its advertising sales, which he credits to the advertising director at the time.

“We never cost the University a dime,” Campbell said. “I was so proud of that.”

Campbell’s year as editor was atypical. The Graphic has received funding from Pepperdine through various means throughout the years. Smith said although the University partially funds the organization, the administration does not have a say in publications.

In providing essential news, student publications have had varying interactions with University leadership.

Campbell said during his time at the Graphic, the paper had an amicable relationship with administration, as Campbell knew President Norvel Young personally before becoming a student.

The front page of the “Sex Issue” of the Graphic features the Dolores statue that stands near the Tyler Campus Center on Pepperdine’s campus. The Graphic published the “Sex Issue” in 2014.

FALON BARTON PEPPERDINE AND GRAPHIC ALUMNA

“When anything between the newspaper and the administration occurred, I would get a call,” Campbell said. “If I had to go to the office, I knew it was serious. If it’s on the phone, it was no big deal. I can hardly even remember the issues, but it was kind of fun to have that access to him.”

The Inner View, however, did not escape backlash from administration during its short tenure on campus. For instance, the Inner View would often include advertisements of local businesses — a notable example being a nightclub called Whiskey A Go Go — that would receive criticism from administration, Wilson said.

“Those are the kinds of things you have to be very careful even unknowingly that they would object to, would call me in, so there were things like that that you wouldn’t normally think twice about,” Wilson said. “But they were very sensitive at the administrative level. So it was a very, very conservative environment.”

Smith said the Graphic today has an advertising policy that does not accept advertisements from bars, night clubs or other businesses that promote alcohol or drugs.

Wilson said the administration during his time as adviser also frowned upon the newspaper from reviewing certain movies.

“We’re not talking about X-rated movies; we’re just talking about regular theatrical releases,” Wilson said. “And word would get back that the administration is upset about this movie, and [say], ‘We don’t advise or recommend our students go see those kinds of movies.’”

Wilson said, in his role as adviser, he had to find a balance between protecting students from administrative backlash and not acting as a censor.

“You’re operating in an environment where the parameters are narrower than in other places, so it was a very interesting time,” Wilson said.

There were certain things not worth “going to the mat” over, but there were also stories that were worth standing one’s ground on, Wilson said.

One story, in particular, involved Norvel Young, Pepperdine’s third president and chancellor at the time, getting into a car crash. While driving under the influence, he got into an accident that killed two women Sept. 16, 1975, according to an LA Times article.

One of the administrators called Wilson and told him the Inner View could not run the story about the crash, Wilson said. Pepperdine’s fourth president William Banowsky also threatened to fire Wilson if he didn’t pull the article.

“He said something to the effect — this is Banowsky — that ‘Well, I don’t need to tell you what will happen if you run this story,’” Wilson said. “And I said, ‘Well, I’m prepared for that.’”

Wilson said he told the Inner View editor to publish the story because of his and the paper’s commitment to journalistic integrity.

The Graphic, on the other hand, did not run the story, Wilson said.

“As a consequence, from the standpoint of professional journalists in the area, the fact that the Graphic did not have the story, and we had the story in the Inner View, and everybody else in the United States had the story, made the Graphic look very bad,” Wilson said.

The Inner View set a precedent for Pepperdine student publications through its commitment to journalistic integrity, emphasizing the administration does not have a say in student-run news organizations.

In more recent controversy, the Graphic published a story on alleged hazing within Pepperdine’s Water Polo team in 2016 that received attention from administrators.

“We were treated like journalists, and an administrator came and kind of had some thoughts for us and sat Falon down and was very upfront about those thoughts,” Nate Barton said.

Falon Barton said although the conversation was serious, she thinks it was a productive and respectful one, and she and the administrator became friends after.

In 2012, when LA County Sheriff’s Deputies arrested President Andrew K. Benton’s son after alleged threats against his family, Smith said the Graphic decided to publish the story the next day because the staff did not want to publish anything until they could confirm the information.

The Graphic often reports stories that University administration might not like, but much of Smith’s ethos as an adviser is to ensure the Graphic is never inaccurate, illegal or unethical in its reporting, Smith said. In the event of missteps, the Graphic will be transparent about it by publishing corrections or updates.

Falon Barton said she felt very grateful to have Benton as part of the administration during her time at the Graphic, especially after hearing stories of what other college newspapers endured from their administration.

“He responded to every email; we shot an email, and he would always respond to us — just spectacular and phenomenally supportive of student journalism at Pepperdine,” Falon Barton said.

Benton shared with Smith how the Graphic’s careful reporting on the situation with his son gave him new insight into student journalism. Smith said she thinks it showed him that the Graphic wasn’t out to get him but rather out to do a job and do it well and with ethics.

A Sense of Duty

Campbell said the Graphic gave him the background of making a newspaper of interest and of value to its audience. What kept him going was knowing there were always better ways of getting the word out and keeping the community informed.

Especially when he wrote for News, Nate Barton said he felt a strong sense of duty to inform.

“I think there is something really unique about working for a newsroom — working for the Graphic, specifically — that I got work experience and life experience and relational experience that no one else I knew of, especially during their early years,” Falon Barton said.

Smith said she thinks the Graphic’s present readership is strong, especially now, because many people look to the Graphic for information first.

For example, in fall 2018, the Graphic covered a nearby shooting at Borderline Bar and Grill in Thousand Oaks and the Woolsey Fire.

“During the Borderline shooting and the Woolsey Fire, we were truly the only news that was coming out from inside the Woolsey Fire,” Smith said. “The media couldn’t get in and out, and so that was a moment where we were very aware that every word we were putting out about this, the world was watching.”