14 minute read

FIRECRAFT NW

FIRECRAFT NORTHWEST

A one-person outdoor education operation

Advertisement

By Ian Haupt

Rubbing two sticks together. Put so simply, it sounds trivial. Yet it was necessary for all that’s come after: The moon landing, TikTok, 7.9 billion people sustaining life on this rock and for you to read this now. All of which have separated us from nature. But through it and other activities, we can reconnect with nature.

Naturalist and wildlife tracker Ryan Johnson, who started his own outdoor education operation, Firecraft Northwest, said he felt closer to nature the first time he made fire by friction, and he’s seen it in the eyes of his students too. He said he also continues to experience it through animal tracking.

Johnson said when coming upon an animal track “we get an opportunity to tell the story of what happened even when we weren’t there and we didn’t get to see it.” This story and the required piecing together of the passing animal’s movements — through its tracks, gait, disturbances and behavior — builds a bridge between the tracker and nature, he said.

For those who attend his workshops — two of his favorites being friction fire and animal tracking — Johnson hopes part of what they get out of his class is a newfound connection with nature and the perspective of human beings as a part of nature, opposed to human beings against nature. “Once upon a time human beings lived in accordance with nature, if there’s a takeaway from some of my workshops and classes I hope that’s part of it.”

Johnson, 33, has been leading nature courses since 2014. He started as a volunteer for school field trips at Oxbow Regional Park in Gresham, Oregon, east of Portland. As a trade for his volunteer hours, Johnson received naturalist training for free. After two years he was working for the park while working in restaurants and as a lab aid. But running classes for the park, he said he couldn’t see himself doing anything else.

Johnson created Firecraft Northwest in April 2021, and said the pandemic played a role in its launch. His administrative job was fully remote. And with people getting vaccinated and back outside, the time felt right.

So far, Johnson has led spoon carving classes, friction fire classes and knife sharpening classes at the Chuckanut Center, where many of his woodworking classes are held. The center, beside Fairhaven Park, is a community-funded nonprofit, run by volunteers, that offers urban homesteading skills, gardening and cooking classes.

Johnson runs his wildlife tracking and survival classes out of the Bell Creek Nature School in Deming, on Mosquito Lake Road, and on the divergence of the Nooksack River’s north and middle forks. With 10 acres of old-growth temperate rainforest and riverside, the nature school provides space to explore and practice learned skills.

Johnson said one of the reasons he created Firecraft Northwest was to make outdoor education more affordable and accessible.

Most outdoor education opportunities are expensive, Johnson said, and he wanted to make them available to people from all income groups. Classes range from $25 to $65, with the more expensive classes offered on a sliding scale. “Having access to wild spaces and learning about nature and survival skills is something that is really enriching for everybody,” he said.

He also hopes to provide a space for families to share nature experiences. Many outdoor education classes are age-dependent, whether they are day camps or field trips to homesteading and gardening classes. He said he wants Firecraft to be a place for families to do these things together.

Johnson has multiple certifications including as a Pacific Northwest naturalist, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife hunter’s safety training, and wilderness first responder. He also has a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry and psychology from Arizona State University.

Johnson said he’s mostly worked with kids. And he said watching their progress, whether it be in tracking or crafts, is one of the most powerful feelings.

He recalled a course he taught with another instructor on overnight shelter building. They had adolescent students build their own fire and use it to keep warm through the weekend. As a challenge, Johnson said he and the other instructor held onto the students’ sleeping bags. They told the group, who said “OK” to the challenge, if they feel uncomfortable or get too cold, to let them know and they would give them back their sleeping bag.

“It was supposed to be a challenge for them, so that they could see what that felt like — to have to stay overnight at a shelter and tend to their own fire to stay warm,” Johnson said. “It’s a really powerful feeling.”

At one point during the night, a 12-year-old girl asked for her sleeping bag. The two gave it back, as promised. The next morning, Johnson said she woke up, came over to camp and told them she had nothing to fear the night before. “I woke up this morning, I looked up and there was a little bit of frost accumulating on my face, and all the birds were singing, and everything was so beautiful,” she said. “I had nothing to be afraid of.”

Johnson said he teaches for those moments.

For more information on Firecraft Northwest, visit firecraftnw.com. x

Our new office is located at 108 Commercial St. Stop by and let us assist you with any trip-planning needs and more! 360-466-4778 l www.lovelaconner.com

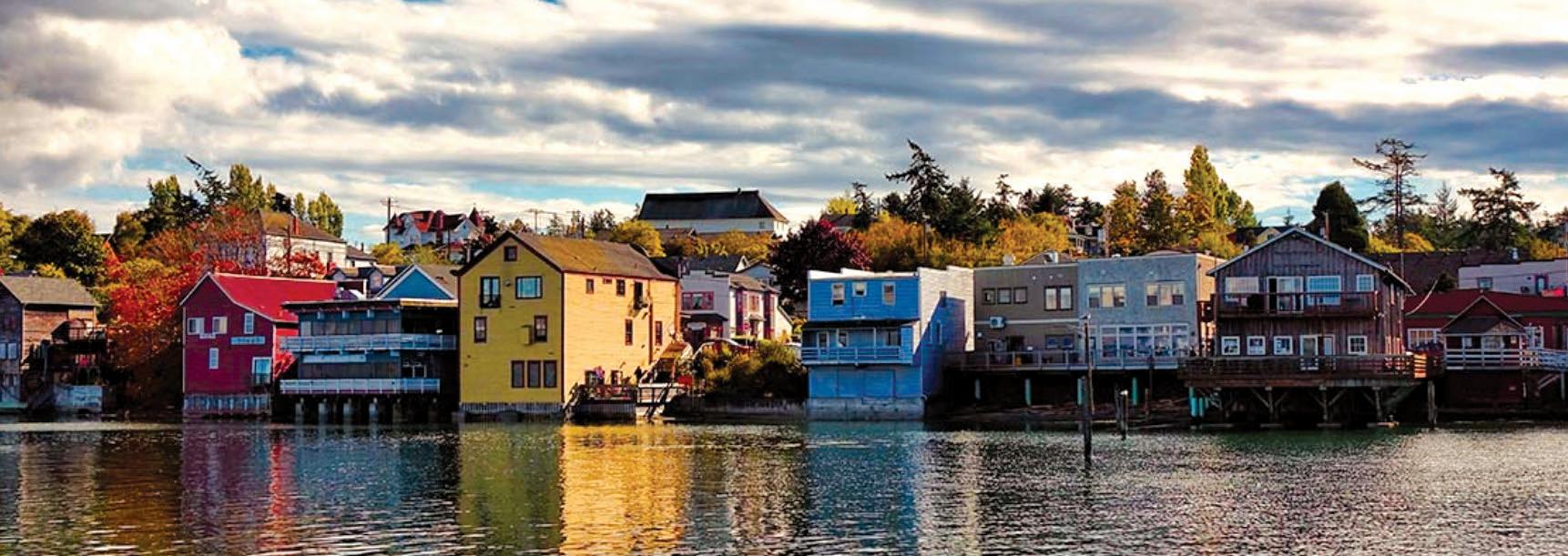

Experience Coupeville on scenic Whidbey Island

Come for the day or weekend and experience a slower pace with fresh air, friendly people and amazing sunsets.

We Ship! Local authors, New releases, Books, Maps, Cards, Stickers 16 NW Front St. Coupeville, WA 360-678-8463

Explore our walking and biking trails Stroll our historic district with its unique shops, restaurants and art galleries. Stay in one of our Bed & Breakfasts, Inns and Vacation Rentals.

Events throughout October. Visit hauntingofcoupeville.com

for list of events

Iverson Insurance

AGENCY

Please remember when visiting Coupeville to wear a mask - thank you!

Sucia Island boat camping

Story and photos by Jason Griffith

The sky seemed to have merged with the sea, except the stars below the horizon were like fireflies winking on and off, too numerous to count. I’d never seen bioluminescence* like this.

The slightest movement in the water left a wake of blue-green sparkling fire that slowly faded to black over several seconds. A rock tossed into the depths was like a comet with a trail visible from surface to bottom. Fish scattered, and underneath was like sheet lightning, the depths disturbed. Even better, there was no moon to drown out this light show.

I couldn’t help but lay on the dock, staring into the water, trying to comprehend what I was seeing. It was too dark to take decent photos (without a tripod, which was back at camp) — photography being my usual way of processing something remarkable. But it also provided the opportunity to reflect on the week we had spent boat camping on Sucia Island Marine State Park in the San Juan Islands.

Truth be told, we weren’t even planning on the San Juans until a short time before we left. Our original plan was to journey into Canada, but with the border closed to “non-essential” travel (vacations are essential!) meant we were left casting about for a Plan B.

Growing up I had often spent a week in the San Juans each summer, so it was an easy pivot, which afforded added bonus of seeing the islands through the eyes of my two boys, 10 and 12. It wasn’t hard to convince two other families to join us and the plan was set … if we could secure campsites.

The campgrounds in the marine state parks in the San Juans are first-come, first-serve, which works well for people like us who planned a trip last minute, but also poses a problem in that one could arrive to find all the sites taken at the chosen destination. Therefore, we had several other campgrounds on nearby islands scoped out as backups. But we never had to resort to Plan C since we scored the sites we needed for our group on Sucia. We were set.

Each day was a blur of activity as we took full advantage of our unique location. Some days we wouldn’t leave the island, lazing around camp drinking coffee in the morning, hiking to various destinations in the mornings and afternoon, beach combing, and watching the kids amuse themselves on the beach.

Sucia has about 12 miles of trail that access many areas of the 814-acre park and we tried throughout the week to walk about every trail at least once. It is an intricately shaped island with over 77,000 feet of shoreline, so there are many hidden coves, beaches and points worthy of exploration. While we could’ve spent the entire week on Sucia, there are so many other islands nearby to explore. And so we found ourselves on six other islands throughout the week.

On some we hiked, others we only sat on the beach and relaxed, and others we picnicked and swam. All had their own characters, their own histories, their own details to observe and compare. We were amazed at the diversity in such a small area. For example, on Jones Island we saw cactus growing on a windswept point with Western red cedar dominated wetlands just a few hundred feet away. On another, Garry oaks, madrone trees and wind pocketed sandstone combined to make that look that says, “you’re in the San Juans.”

But no matter where we were during the day, we always returned to our camp each night to fantastic dinners, campfires and sunsets watched from the bluff a short hike from our tents. Campfires and s’mores were the standard aperitif (you don’t want to try and put a kid to bed camping without s’mores) as the lights winked on boats swinging at anchor in Fox Cove and Fossil Bay and the stars came out.

Then, after dark, it was time to head to the dock to look into the water and think. x * Bioluminescence is light produced by a chemical reaction in a living organism. In Puget Sound most instances are caused by blooms of a single-celled plankton named Noctiluca scintillans aka “Sea Sparkles.” During warmer months, the population of the organism can explode, leading to large patches of the reddish algae visible during the day near the surface. At night, the blooms lead to episodes like we witnessed on Sucia. Noctiluca luminesce (glow) when physically disturbed, which is believed to be a defense mechanism to scare off predators.

IF YOU GO:

Most campsites in the Washington’s marine state parks are available on a firstcome, first-serve basis. Sucia Marine State Park has 60 standard campsites, four reservable group camps, four picnic shelters, portable drinking water at Fossil Bay early April through September, Echo Bay and Shallow Bay May through September and composting toilets. bit.ly/3yWvxr4.

Hart Steens odyssey Hart Steens odyssey Hart Steens odyssey

A road trip to the Northwest’s ‘real West’ A road trip to the Northwest’s ‘real West’ A road trip to the Northwest’s ‘real West’

Story and photos by Eric Lucas

IIII’m a middle-age white guy in a 1999 4Runner, V6, 206 cubic inches, 4WD, steel-belted Michelin truck tires. He’s a pronghorn buck, 2016 vintage, 206 pounds, 4-leg drive, keratin tires. Who’s gonna win? No contest. And not just because the back roads on Hart Mountain National

Antelope Refuge are really sketchy (they are) but also because the pronghorn antelope is the fastest land animal in North America. He could still beat me on a well-maintained gravel county road, inasmuch as antelope can reach 50 mph in short bursts.

I’ve come here in two long bursts from the Salish Sea. Eight hours drive, a stop in

Pendleton, then 6 more hours to Hart, and I’m in a place so radically different from my island home that it’s another universe. This is my favorite Northwest road trip.

Contrast is good for the soul. Uniformity is life’s fast food; come to Steens Country and there’s no fast food for hundreds of miles. Instead, there are pronghorn/car drag races.

Of course, the buck isn’t on a road. I am, bucking along a pavement made of desert dust, sagebrush roots and basalt. He’s dashing through the sage about 20 yards away, clearly enjoying our race across Guano Flats at the far southern end of the refuge.

Why are we racing? Biologists believe pronghorns like to match their speed against cars for, well, fun. And why not? We can’t catch them. Nobody can, really. Hart Mountain’s healthy cougar population focuses on deer and bighorn sheep, and the few hunters who prowl the refuge in the fall do best from blinds. But race-car pronghorns are just the start of innumerable non-Pacific things one can see and do around this part of southeastern Oregon.

“The Steens,” as locals and fans call the area, is anchored by Hart Mountain’s 8,017foot fault-block monolith, and Steens Mountain itself 60 miles away, a 9,733-foot behemoth that is by far the biggest thing for hundreds of miles. The entire region is larger than many European countries, but has less than 15,000 residents. Drive to the top of Steens – the highest auto road in the Northwest – and as you step over mid-July snowdrift remnants, you can gawk straight down almost 6,000 feet to the flat salt plain of the Alvord Desert. Once you’re done gawking, you could also:

• Stop to admire the mountain’s 300-strong wild horse herd. Desert advocates grouse that these are “feral” (non-native invasive) animals; and so they are, descendants of late 19th century ranch and cavalry cavvies, but beautiful and inspiring nonetheless. • Watch the roadsides carefully for badgers, rattlesnakes, mule deer and golden eagles perched on fence posts like emperors. • Hike three miles up Big Indian Creek to a high meadow where the area’s Paiute inhabitants used to bring horses to race during summer high-country camps. • Get stuck behind a cattle drive on the East Steens Road, which parallels the Alvord Desert at the foot of its namesake mountain. When you finally can pass, the cowgirl lifts her broad-brim hat in greeting. • Pull off to soak in the blissful, 108-degree mineral-rich waters of Alvord Hot Springs, where the view itself is larger than Liechtenstein. • Cast a Woollybugger fly into tiny pools in mountain streams for the rare and beautiful red-band rainbow or Lahontan cutthroat trout, both uniquely adapted to the harsh desert environment. • Make camp amid shimmering aspens at Hart Mountain, setting a couple of trout to cook over a spicy juniper fire. Later, lie awake listening to nighthawks dive in the dusk. • Or pull into the Frenchglen Hotel at 6 p.m., because it’s the only lodging for miles and miles, and the hotel’s ranch supper is “promptly served” at 6:30 p.m. sharp and laggards lose out. Maybe, if you’re late, there’ll be some peach cobbler left. Maybe not.

Oregon tourism officials label the state’s dry eastern side the Oregon Outback. I favor Ian Tyson’s description, the Sagebrush Sea. Frenchglen, the “town” in the center of the Steens, consists of eight buildings, one street, one store and one restaurant, with oceans of sage and juniper in every direction, interrupted by cottonwood armies along a mountain-born river named Donner & Blitzen (“thunder and lightning” in German). Here, in the riverside lowlands watered by the Steens summit snowmelt, enough lush grass grows that 150 years ago an enterprising cattleman named Pete French established the largest ranch in the country, the P Ranch. Though the town is named for him, his more famous legacy is as the cattle baron gunned down by a homesteader in 1897. Yes, just like in the movies.

Today’s cattle barons run smaller ranges, and coexist largely in peace with the 21st century pilgrims who come here to bird-watch, hike, sightsee and breathe sage air that I believe is an antidote to everything from modern malaise to Covid.

I can’t prove that, but I’ve been here almost every year since Bill Clinton was president. Native Americans burn sage to banish evil spirits; each year I bring some back from the Steens and in my home the desert’s sharp scent easily bridges the 500 miles between my island farm and the Sagebrush Sea.

And eventually, each year, the pronghorn pacing my car pull up and remind me that life’s not really a race. I get out, listen to the quiet, breathe in the sage, and salute their good common sense. x

Eric Lucas is the author of the Michelin guide to Alaska. He lives on a small farm on San Juan Island, where he grows organic hay, garlic, apples and beans.