24 minute read

PARKING PROJECT

Parking continued from Page 12

ham, among other sources.

Advertisement

The project will be completed by spring 2022. The second phase of the project wrapped at the end of November, reopening the original lot for the winter. The third phase is scheduled to begin March 2022.

WMBC board president Bill Hasenjaeger said the project’s completion is dependent on temperature and when the construction contractor can lay asphalt. During the winter, a handful of small tasks will be done to prep the lot for the final phase. Ram Construction General Contractors will then lay asphalt in the spring when temperatures are right.

“Laying asphalt will be the last thing done, which is weather dependent,” Hasenjaeger said.

He also said Whatcom County will be installing a lighted crosswalk on Samish Way from the new parking lot to Galbraith Lane. This will connect the Lake Padden trails with Galbraith Mountain. At the time of publication, the county had yet to approve the crosswalk.

“Recreation Northwest and WMBC have worked together over the years to help further our shared values as related to our complimentary mission statements,” Ellsworth said in the release. “When our Angel donor offered to help our friends get their parking lot to the finish line, we were ecstatic to be able to offer the gift.”

For more information on the project, visit wmbcmtb.org/galbraithparking. x Photo courtesy Eaglecrest Ski Area/Travel Juneau Creamer’s Field, a marvelous park where you can ski over a sublimely picturesque footbridge in snowy woods, just like in a movie.

Alyeska and Moose are joined in downhill distinction by Ski Land, north of Fairbanks, which is the northernmost lift-served downhill area in North America. The view from the top here literally encompasses the Arctic Circle about 50 miles away. East of Fairbanks, military staff and family members at Fort Wainwright take to their own on-base slope, Birch Hill … How cool is that? And Eaglecrest, near Juneau, has sensational mountain and sea views to match Alyeska, and shares with it the saltwater air found at virtually no other ski resorts on Earth.

None of these places are crowded. Anchorage and Fairbanks are 4 hours by plane from Seattle, and farther still from anywhere else. You have to fly to Juneau — no road reaches Alaska’s capital. Theoretically, you can drive to Fairbanks and on to Anchorage on the Alaska Highway. Suffice to say that ski travelers who do come this far north will never risk being flattened by an L.A. hotshot going 90 mph whose 5 cans of Monster Nitro dissolved his brain at 9 a.m.

But they can savor the sight, scent and sound of hoarfrost in birch woods on a 10 below morning — balmy for Fairbanks. They can take a last run, duck in the lodge for hot chocolate and come back out an hour later to scan for the Northern Lights.

You may even see a moose at Moose Mountain. They’re not allowed on the school buses, though. x

Eric Lucas is the author of the Michelin guide to Alaska. He lives on a small farm on San Juan Island, where he grows organic hay, garlic, apples and beans.

Plans for the new parking lot project. Courtesy WMBC (below) The project site on November 22, 2021. Ian Haupt photo

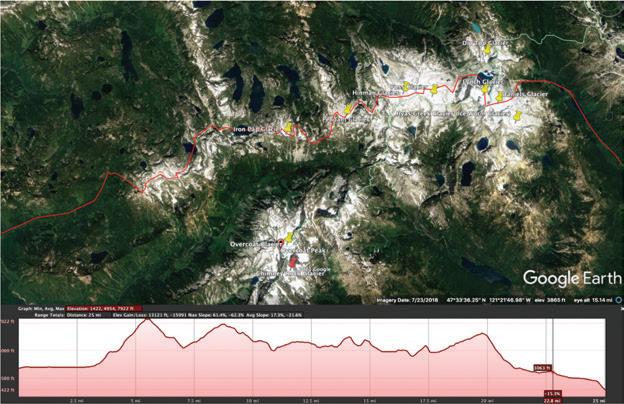

Mt. Daniel to Big Snow Traverse

Story and photos by Jason Hummel

Alex Kollar (1993-2021)

Adventures are like bus stops on the way down memory lane. One stop in particular has become all too familiar. It was a rare mid-winter ski traverse through the heart of the Alpine Lakes Wilderness with my friend Alex Kollar. What we found together was a Shangri La bathed in sunshine and endless fields of powder. More importantly, what I found was a new friend worth planning future adventures with, a rare individual who enjoyed my brand of suffering and exhilaration in the mountains.

Alex was a guy who smiled after he went headfirst into a creek and grinned when I explained I'd gone ass over teakettle through the forest. When we finished our four-day traverse and prepared to drive out, Alex saw a father and son stuck on a muddy side road. He didn't hesitate to wade through the mud barefoot to push them out, and laughed like a maniac when we got stuck in the same predicament a few moments later.

I will never forget Alex's go-to "Yeah, buddy" on a great downhill run. I'm sure he brought that same enthusiasm to the Deschutes River in Oregon. Sadly, he never made it out this October.

So now, when I'm riding down memory lane, I find myself stopping on this adventure. Step off the bus with me, and enjoy the journey!

As snows fall and winter winds march across the Alpine Lakes Wilderness, this mecca so many hikers tread and trod from one end to the other reverts back to a nomans land, winter bound and silent except, that is, for the occasional backcountry skier, like myself. For us, winter isn’t a barrier but a means to an end. Snowbound valleys become canvases to cut fresh trails across and snow-coated mountains become playgrounds to summit and descend from.

When it comes to winter wonderlands, few places curl up in my soul and become a part of me through and through as much as the Alpine Lakes Wilderness has. A direct result of not only my fascination with its sharpened pinnacles and bejeweled valley’s full of sparkling lakes, but because I get to visit this region over and again, year after year, and see the shift and shuffle of change in the world without, while time remains frozen in the wilderness within.

Variations of the Alpine Lakes Traverse have long interested me, but inspiration to tackle this particular version, which goes from Mt. Daniel to Big Snow Mountain, came from my need to visit glaciers for my Washington Glacier Ski Project. These glaciers included the Dip Top, Iron Cap and Pendant glaciers.

March 9: Deception Pass Trailhead to Pea Soup Lake, Mt. Daniel Summit

Under the heels of an angry snowmobile, 11 miles of road swept by in a spray of ice that thwapped my head. The praying sort would ask not to be keeled under sled tracks or dragged hogtied by a heavy pack across the icy road, but I like danger, it turns out, for about 10 miles. Only 11 miles of road later, Jake and Matt, who piloted Alex and I to the trailhead on their stallions, finally pulled up at the end of the road.

Jake and Matt joined us on the ascent of Mount Daniel. While there are many approaches to the summit, for expediency’s sake, we bypassed Cathedral Peak and made a direct ascent of the mountain. We toured past Hyas Lake (Hyas means ‘big’ or ‘great’ in Chinook jargon) and ascended a couloir I dubbed Killer Cornice Couloir because, of course, it’s as much a killer place to have lunch as standing under a crane that’s moving a piano to the top story of a city apartment.

Some few hours later, in a cold huddle near the top of Mt. Daniel, Alex and I split ways with Jake and Matt who were returning to their stallions and town, to cold beers and warm beds. While they vanished into wind and fog, Alex and I continued upward, soon becoming lost in the white miasma. Having been to the summit of Daniel a dozen or more times, I set out confident that I knew the way. Only, in reality, I didn’t. When we reached a summit we discovered that it wasn’t actually the summit at all, but the top of the east peak of Mt. Daniel.

With the help of the ‘of course, you’re right’ GPS, we made our way to the actual summit. Bruised dignity aside, the slow shuffle around the summit towers brought me back to the present. A distracted mind could, say, be unknowingly walking the plank, since cliffs abounded above and below, appearing in and out of the fog like ghouls.

All day (even with evidence to the contrary) our expectation was that the sun would grace us with her light. Instead reality provided a face full of graupel and the

omnipresent buzzing of metal that comes with a charged atmosphere. A sure sign that it’s time to not be standing on the highest point around. Even so, I yelled to Alex, “Look at those beautiful lakes and how about that Lynch Glacier? What a view!”

We laughed and retreated to a small pass just above the aforementioned glacier and from there dropped toward Pea Soup Lake.

Like two sea captains, we piloted our skis through the fog and somehow remained standing. After we arrived at Pea Soup Lake, I canonized the moment by saying to Alex, “How appropriate to arrive at Pea Soup Lake in a pea soup fog.” In the wind and snow I couldn’t tell if he laughed or groaned.

Midway across Pea Soup Lake, fog retreated and revealed our descent tracks. They were as if two children were given a white wall and markers to scribble with. Alex quelled my embarrassment over our ski signatures when he assured me that, “The snow will cover them by morning.”

March 10: Pea Soup Lake to Pea Soup Lake to Iron Cap Pass, Mt. Hinman Summit

Calm winter mornings are as silent as they come. Attempting to not break that peace and quiet, I crept out from the tent like a child from his room on Christmas morning. My present was a solo side trip to Dip Top Glacier. On my way there, the slopes unwrapped from behind ridges. As I crept up powder-filled slopes, I felt the kind of thrill only the unexpected fulfills.

Atop Dip Top Gap I skied onto the now-stagnant north facing Dip Top Glacier toward Jade Lake. In the midst, alone among all that disappearing ice, looking out onto a horizon of peaks, I felt that I was among friends, however non-corporeal they may be. Friends are always there for you, as are these peaks.

Back at camp, I rejoined Alex and we herded our gear into packs and descended from Pea Soup Lake to the valley below in a daze. For, there it was, that sunny powder we’d been jiffed of the day before. Our surging thrill came in waves, like the snow that was sent flying with each turn.

Hearts quieted after a short but earned for descent. After which we climbed the Lower Foss Glacier and the gentle slopes of Mt. Hinman whose slopes I’ve found unusual. Glaciers tend to create steeper north faces than south faces, in general. Hinman bucks the trend.

When we arrived to the crest of the ridge, the views assaulted us like scantily dressed ladies at a ball.

We tore ourselves from the views and traversed Hinman Peak until we descended to La Bohn Lakes. As I skied toward a blind rollover, I thought Alex waved me on. Just a few feet before the edge, I hockey stopped on icy snow, the worst we had the entire trip, and only then learned from Alex that his wave was telling me to stop. Because I couldn’t help myself, I did some quick and dirty math and my former trajectory didn’t add up to anything pretty.

With my excitement sufficiently checked, we descended the remaining slopes to Necklace Valley and from 4,900 feet we climbed onto the Pendant Glacier. Cloud shadows chased us across my second un-skied glacier of the trip. While I’d hiked through this terrain often, I find skiing through it so very different. In the winter, the high country reverts to its natural self: Wild and untrammeled.

Across Upper Tank Lakes was only recognized as a lake as I’d been there in summer. About halfway to Iron Cap, along a gentle bench, the views of the mountains grabbed us up and steered our skis to the rim of the valley. By the time the glamour was broke, dusk and sunset were upon us, so we decided to drop packs and camp. Sometimes stopping is worth hurrying into, the only distance worth gaining. When going further doesn’t get you anywhere that matters.

March 10: Iron Cap Pass to Gold Lake, Iron Cap Summit

A lazy and tranquil morning drew out the hours and before we knew it, noon was fast approaching. Since a warm day was bad for a crossing beneath Iron Cap, our tardiness was a regrettable oversight. Fortunately, conditions remained stable, but by then worry had already lit a fire under our asses, so we made short work of the mile-long traverse and boot pack to the crest of the north ridge. Slower, though, was the serpentine ridge to the summit; we couldn’t help but stop every 10 feet to take in the views ahead and behind us.

Immediately below us was the Iron Cap Glacier, which is stagnant ice today. The lake at the bottom is one of those newly formed in recent decades, a left over from glacier retreat much as the lower altitude lakes were leftovers from the last glacial surge of the Puget Arm of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet about 16,900 years ago.

Instead of wrapping around the shoulder of Iron Cap Peak, we decided to ascend 500 vertical feet over a ridge for a direct descent to Chetwoot Lake. At the top once more, another field of powder lay below, just as drool-worthy as the last, and after we ate up the vertical like starving shipwrecked survivors, we coasted onto the lake. All along the way sun speared through clouds, snow blasted around skis and we found ourselves suddenly stopped, feeling lighter no matter our heavy packs.

While we could either go over Wild Goat Peak or around it, we chose the more conservative route. It turned out to be the right decision. We found terrible snow on our ski to Gold Lake. We pitched camp on the lake ice and after the sun went down, I watched the starlight glint on snow crystals as I cooked a mountain feast fit for only hungry climbers.

March 11: Gold Lake to Dingford Creek Trailhead, Big Snow Summit

Morning awoke to light spreading across Big Snow Mountain and Gold Lake. Alex and I didn’t budge a muscle until it rolled over us like a slow rising tide. Eventually, resigned to our last day, we gathered gear and skinned across the lake toward a serpentine streambed. This led us from the flat, frozen lake toward gently rising and rolling terrain, which offered easy access to the uppermost slopes of Big Snow Mountain.

I’d like to say that a summit doesn’t attract me, but I’d be lying if I said it didn’t. What’s more is that the best traverses in my mind are those that add summits and descents in conjunction with horizontal movement across or along mountain ranges. That’s why going over the summit of Big Snow was part of this adventure. It shows how much work there is to do out here in this tiny corner of the Cascade Mountains. These (big) little peaks that surrounded us have character; different moods and faces that keep all of us guessing as to their true nature.

Once our boards were snapped on, our reward besides the views, which were kid in

a candy store kind of ‘google-eyed’ awesomeness we never get enough of, was the descent. Striking down the west shoulder of the mountain was a beauty of a line that would be the gobstopper of the trip. Usually I would take photos of such a descent, at least a few, but this time I put my camera away. Even a few shots can distract me from having fun of my own. Besides, soul turns mean soul turns.

And on the descent my ‘soul’ sang. Sadly, what also sang, except out of tune, were my legs. Not wanting to stop, I careened down the slope like a runaway train. Somehow I didn’t yard sale. Neither did Alex. After our final turn, we pointed our skis back up at the line. As it came into view, smiles grew, and I silently promised to get more ‘soul turns’ in the near future.

Every valley in Washington begins in the Cascade Mountains and every mountain in the Cascades Mountains ends in a valley. So it was that we descended into the forest. Between losing the trail and for the fact that there wasn’t quite enough snow to cover logs, rocks and debris, we were like a ski ballet troupe doing never ending practice rounds where we ducked and stepped, bent and danced, tripped and fell and, well, you get the point.

There was a point when Alex, caught up in the rhythm of our race down trail, when he was swept up by the rocks and cast sidelong into a creek. Swimming and skiing don’t usually go hand in hand, so when it happens there’s a full helping of laughing, moaning and, after which, the race goes on.

A few hundred yards before the end of our trip, I laid down my skis after going far too long on too little snow (something I’m more proud of than I should be), and waited for Alex.

It’s important to take a moment to look over any adventure you’re on and take it all in — to give it its due in the moment, not after, when you’re home. It’s been a crazy year with Covid-19, and ski adventures took a back seat for the first time in my life. That is why this adventure felt rejuvenating for me, a reminder of why I still push myself to go to these places. Yet, it also reminded me how much they mean to me, not in that I can’t exist without it kinda way, but in that I feel at home out here kinda way.

When Alex arrived, we walked the final yards to the truck and to beers of our very own.

Later, as we were helping a stuck father and son pull their rig from their proposed camping spot above the Middle Fork Snoqualmie, sans shoes and in ski clothes, Alex and I had to laugh when our kindness resulted in us also getting stuck. “At least we have our camping gear,” I told Alex.

Fortune was with us, though. A couple with a winch drove by just as dusk was falling. With their help we were once again on our way, mud splattered and thankful. It just goes to show, the adventure isn’t over even after you’ve returned to civilization.

Find a video Alex made of the trip online at mountbakerexperience.com. x

Greater Ranges

A winter ascent in North Cascades National Park

Story and photos by Jason Griffith

he North Cascades are notoriously rugged. Even in

Tsummer, steep terrain combines with thick brush, unmaintained trails and changeable weather to challenge the strongest mountaineer. In winter, the range is even less kind. Wreathed in storms for weeks at a time, riven by avalanches that can break old growth trees like matchsticks, the heart of the North Cascades remains a mystery, especially those areas distant from highways 542 and 20.

This started to change when John Scurlock built his tiny yellow plane nearly 20 years ago and took to the skies over the North Cascades. He documented wild winter vistas that the rest of us could hardly believe were in our backyard. And so, a new generation of climbers was transfixed, transformed and mobilized to seek out the challenges that the range offers in winter.

I was one of those climbers, familiar with the North Cascades in summer, but mostly considering it off limits during the short days of midwinter. However, the combination of John’s images and the up-to-date information on the message board “CascadeClimbers.com” had a way of slowly drawing me in. Image after image, trip report after trip report, my fear began to wane until I found myself looking at the long-range forecast in February of 2015, wondering how the NW Couloir of Eldorado Peak was looking.

Wondering, that is the operative word. Snow and ice are fickle mediums. It is often hard to know exactly how a climb will be unless you take the gear for a walk and see for yourself. I was lucky that I had a few others in my circle that also didn’t mind going on long, potentially fruitless walks in the middle of winter. This included Chuck and Tim, former ultra-marathoners and keen climbers, who, like me, were eager to see the North Cascades in their winter glory.

Chuck and I left the Eldorado climber’s lot Saturday morning at a reasonable hour, beginning to trudge over a vertical mile up to the base of the East Ridge of the mountain. Tim maintained that he would meet us at high camp early on Sunday, but we carried enough gear that we could complete the climb if he didn’t make it in time. The “trail” up to Eldorado isn’t much of one, more a straight up boot beaten line that tells you where to go. Where it fades into a boulderfield, we punched through shallow snow, trying to keep from twisting a knee on our way to camp. In the North Cascades, often the crux of the trip takes place below treeline, and winter doesn’t make the lower elevations any easier.

Chuck had forgotten his ski poles, so he grabbed a sturdy stick in the forest and broke it off to length. As we climbed higher and stepped onto the glacier, the sight of him plodding along with his stick made me smile. Or maybe it was the views?

Across the valley, the grand sweep of the north face of Johannesburg was impossible to ignore, with her hanging glaciers and snow flutings looking to avalanche at any second. To the east, the graceful pyramid of Forbidden was even more beautiful than usual, its normally bare rocks almost completely plastered in a veneer of snow and ice.

But the light was fading fast, and we had to stamp out a platform for the tent, melt many liters of snow, and battle the rising wind and spindrift. This is the part of winter climbing/camping that I don’t relish. It is hard, cold work. Thankfully, as we tended to camp chores, our friends Jason and Krissy pleasantly surprised us. They were returning from a successful one-day ascent of the standard East Ridge of Eldorado. We chatted for a few minutes, but they couldn’t linger.

Chuck and I settled in for a long, wind blasted night at the base of the East Ridge, wondering if Tim would meet us the next morning. A bright moon lit the scene brightly. A headlamp wasn’t needed, but the cold wind chased us into our bags early. I slept fitfully, as I often do before uncertain climbs.

Would the snow be firm enough … the ice solid enough … the clear weather hold long enough … would we find the rappel anchors? So many questions we wouldn’t know answers to until we committed to the climb.

The day dawned clear, as forecasted, but high clouds were scudding across the sky from the west, heralding the next storm system. As we prepared breakfast we kept glancing south across the glacier, looking for Tim. We could only wait so long, and so we began to slowly stow our gear and put on our harnesses. We were pretty sure he wasn’t going to make it. And who could blame him? This was pretty ridiculous, and maybe even point-

less. The NW Couloir wasn’t certain to be in good shape, but Chuck and I thought we could always go up Eldorado’s normal route as a consolation prize. Having a plan B is always a good idea in the North Cascades, even more so in the winter.

Then, just as we were turning to leave, a dot appeared far across the glacier, moving rapidly toward us. Tim was practically jogging and was soon at our camp, psyched for the day ahead despite the 2 a.m. start from his van. He grabbed one of our ropes and some of the pickets (snow stakes for protecting steep snow while climbing) and we set off across the glacier to find the rappel that would drop us near the base of the route. I grabbed a ski pole as we left camp, and Chuck grabbed his stick. Was he planning on packing it the whole way up and down the peak?

I didn’t have to wonder long, since the rappel anchor was less than a mile from camp. Tim and I quickly set up the rappel, threading both ropes through the anchor, and tossing them to the glacier 60 meters below. Chuck unceremoniously threw his stick to the side, threaded his belay device onto the ropes, and disappeared over the edge. I laughed, imagining climbers stumbling upon this stick next summer, so far from the forests below.

Once we touched down on the glacier, we had a view of the route, and it looked good. Consolidated snow and ice shone in the morning light just a short distance away. Our instincts had paid off. Quickly, I led out toward the couloir, roped to Chuck and Tim in case I punched through into a hidden crevasse. There were no tracks but ours, our senses fully awake to the possibilities, both good and bad.

At the base of the couloir, where it steepened, I stamped out a platform, sunk a picket into the icy snow and belayed Chuck and Tim up to me. Chuck grabbed the remaining pickets, ice screws, and draws and immediately started up. There is no time to waste in the winter and you must keep moving to stay warm. He soon began to encounter more challenging bits, primarily icy bulges over rock steps. As Chuck swung his ice tools, snow and ice chunks rained down, careening off the sides of the couloir. Tim and I huddled to the side as best we could, shifting right and left to dodge the biggest bits, and stamping our feet to stay warm.

This was repeated for several rope lengths as we worked our way up the couloir, Tim and Chuck taking turns to lead the team higher and higher in the cold shade of the gully while I trailed, taking photos. In all, we had found the climb in relatively “easy” conditions. This was just fine with us. We were in the heart of the range in the middle of winter, without another soul around. The jagged peaks around us held snow on their impossibly steep sides looking more like the greater ranges than the modest summits of our backyard. Above, as the climbing difficulties eased, we smiled and shook hands as we stowed gear for the final steps to the summit. It was rewarding to have snuck into the range on a whim and have it pay off so handsomely.

But the rising wind and the thickening clouds tempered our enthusiasm. We didn’t linger on the summit. We snapped a few photos and carefully descended back to camp to pack up and hustle down before the weather arrived. Tired, but satisfied, all three of us were lost in our thoughts as we trudged across the glacier in the late afternoon. The window we had used to sneak into the crystal fortress was about to slam shut. x

Accepting Canadian Cash

Where Your Budz Are

BUY LOCAL