45 minute read

A-Game

At left: Gilmore with the staff of Refettorio Felix in London Page 33: A bustling dinner at the Refettorio Gastromotiva Gilmore with husband Massimo Bottura at Casa Maria Luigia

Food for Soul restores and renovates neglected spaces, transforming them into inspiring community hubs. By partnering with artists, architects, designers, and musicians, Gilmore and Bottura are building a movement in which people in vulnerable situations— as well as the whole community—can feel welcome and valued.

“Imagine a beautiful space, filled with art, music, and good conversation,” Gilmore says. “This sparks social connections. Not just for the people in need, but for the volunteers, the chefs— everyone walking through the doors and joining the gathering. It brings them all together in an equal way. And everybody is raised up a little bit. That is the power of food. We think of food as delicious meals, but food—and the act of coming together around a table and creating a dialogue—transforms how we feel about ourselves.”

Food is both a teacher and a storyteller. One life-changing lesson—and quite possibly the genesis of Gilmore and Bottura’s food revolution—harkens back to 360,000 wheels of ParmigianoReggiano cheese.

Northern Italy’s Emilia-Romagna region, known for its balsamic vinegar and Ferrari sports cars, was not prepared for the destruction caused by an earthquake that hit Modena in 2012. The local dairy-farming community was pulverized and hundreds of thousands of damaged cheese wheels were destined to be thrown away— until Bottura and Gilmore stepped in, masterminding what is now known worldwide as “The Great Parmesan Rescue.”

Featured in the opening episode of the Netflix documentary Chef’s Table, Bottura developed a technique for cooking risotto in cheese to get chefs to buy the damaged wheels. With Gilmore’s communications savvy, they hosted an online fundraiser since dubbed the “biggest Italian dinner in history” on social media.

The easy-to-make and delicious recipe made it into home kitchens and culinary hotspots alike all around the world. Every cheese wheel was sold and the industry was saved.

“It was eye-opening,” Gilmore says. “Chefs are realizing they have a voice, and with that voice is an opportunity to make change.”

She points out that we’re at a critical moment. Almost one billion tons of ready-for-sale food gets wasted every year, most of it at home, according to the United Nations Environment Programme, for which Bottura is a goodwill ambassador.

“We want to communicate that wasting food is not ethical and show people how they can get creative and have real impact,” Gilmore says.

The first refettorio was born as a pop-up concept at the 2015 Food Expo in Milan. Housed in an abandoned theatre, the community kitchen brought together more than 60 international chefs to cook using food leftovers from the Expo. During the six months of the event, 100 volunteers washed dishes, mopped floors, and served over 10,000 meals cooked from 15 tons of salvaged food. Today, the Milan refettorio still serves healthy meals in a beautiful space five days a week.

The project has grown and flourished in cities across the globe, with each location—a historic colonial house in Yucatan, Mexico; an ancient crypt in the heart of Paris; a 100-year-old Gothic-style church in Harlem—boasting its own unique character and style.

“Like the finest dining rooms in the world,” adds Gilmore, a fine arts major, “the refettori are places where food and hospitality combine with art and culture. It is also about bringing dignity to the table, which can be done in many ways—through the power of beauty, the quality of ideas, and the value of hospitality—something we’ve learned over our 26 years of experience at Osteria Francescana.”

The wild success of the Modena restaurant, a 12-table, 34-seat intimate affair in a small town, has allowed Gilmore and Bottura to wield influence over issues they care most about and combine their love of community, art, and food to lead the charge on social impact entrepreneurship.

Three years ago, Gilmore and Bottura launched Tortellante, a project that teaches people with special needs how to make tortellini. Paired with veteran Italian pasta makers, students ages 16 to 25, including their son Charlie, produce tortellini daily for local restaurants, cafeterias, and businesses (including a Maserati car factory). The students gain both skill and pride for contributing to their town’s culinary identity.

When the pandemic made it impossible for the U.S. refettori to open their doors to the public, both locations— along with established refettori around the globe—transformed into brown bag delivery services for the most vulnerable. In Harlem, an average of 600 meals a week are still being delivered to those in need.

“The past couple of years has reminded us how strong we are when we work together,” Gilmore says. “We will always be a community gathering around a table of family, friends, and strangers who will become friends. Food is the binding force that draws us together and reminds us of our collective humanity.”

ANGELO DALBO MARCO PODERI

A TWIST of FATE

The day Lara Gilmore stepped inside her French classroom at Andover, it changed the course of her future.

“I just didn’t click with my teacher,” Gilmore says. “Sometimes it happens.”

So she switched to Italian, taught by Vincent Pascucci, whom Gilmore describes as an elegant, older gentleman from Como, Italy, who came to class every day in a beautiful suit and tie.

“Before we even learned the language, he made us fall in love with the culture—the food, the landscape, the art and music. It really opened my mind up to Europe and European history. And with that, at age 15, began the beginning of the whole rest of my life.”

As soon as she graduated from Andover, she visited Italy, knowing that someday she’d be back. Years later, when living in New York and studying art, she replied to an ad for a bartender at the Caffé di Nonna in Soho.

“I told them I could speak fluent Italian, make a good cappuccino, that I had traveled and knew a little bit about wine. They asked me to start working the next day.”

Massimo Bottura, an Italian who was learning his way around New York City kitchens, also happened to walk into that same café, looking for a job. The pair became fast friends.

Bottura would eventually return home to Italy. In 1993, Gilmore took a leap of faith and left New York for Modena to be with her future husband.

“I feel both American and Italian,” she says. “But when I’m in the kitchen, I feel more Italian.”

Rebecca Schrage ’97 enjoys her favorite snack— a piping hot Schragels everything bagel.

Schmear This!

An old family recipe helped Rebecca Schrage ’97 put New York–style bagels on the map in Hong Kong

very recipe tells a story. For Rebecca Schrage, a marriage of two worlds, family tradition, and new frontiers is where the plot thickens. So it’s fitting that, of all things, a food in the shape of a circle takes center stage in her kitchen.

Bagels, like pizza and mom’s mac and cheese, are one of those hot-button foods that evoke strong feelings. Schrage’s earliest memories involve waking up on Sundays to the heady scent, distinctively doughy and slightly sweet.

“We’d rush downstairs in our pajamas to dig in,” she says. “Weekends at the Schrage house were for bagel brunches with schmears [a generous slathering of cream cheese] and all the fixings—lox, whitefish salad, egg salad, and chopped liver.”

The golden-brown circle, perfectly imperfect, would still be warm as she raised it to her mouth and closed her eyes. This is where her journey began.

Food was the language of love for Schrage’s mother, Elizabeth, who found joy immersing her family in cuisine from two different worlds— Hong Kong, the place of her own roots, and the Jewish food traditions of her husband, Michael.

Schrage’s grandfather, Benjamin Schrage, emigrated from Poland to New York City, where, history confirms, the Polish-Jewish community introduced the unique and tasty bread to America. Benjamin owned and ran New York delis throughout the 1950s and 1960s. His granddaughter, who lived in New York post college when working on Wall Street as an investment banker, is—like any New Yorker—fiercely particular about the bagel. The art of boiling the dough, she says, and the persistence of a technique passed down through hundreds of years separates the real deal bagels from the phonies.

“A great bagel is all about the chew,” Schrage declares. “A thin, shiny, crackly

FULL CIRCLE

Because bicultural and biracial people have two identities within one social domain, their identification is often challenged. When applying to Andover in the mid-’90s, Schrage had to check a race box, and for the first time she found herself having to choose between her Caucasian and Asian identities. She attended the Andover Asian Society meetings because she was strongly connected to her Chinese culture, but still felt like something was missing—something that spoke to her unique experience.

So, Schrage founded the Interracial Student Association (now called MOSAIC), which also welcomed students who were in mixed-race relationships. The students bonded in their shared experiences and also shared with the Academy their frustrations over having to choose a single identity on the Andover application form. In response, the Academy’s application process was updated, enabling students to choose more than one descriptor.

“Growing up in a mixed culture household was so incredibly different. I thought it was important to create a place where interracial students could meet and share experiences, ask questions, and get advice on challenges they might face,” she says.

“The crossing of cultures back then was a big deal,” says Schrage. “I love this photo of my parents with both sets of grandparents. It’s a beautiful representation of love and where I come from.” crust and a dense, chewy interior come requests followed. Schrage purchased from the proper boiling. If it’s not boiled, an extra oven and refrigerator and was it’s not a bagel. Steaming doesn’t count.” soon rising before dawn to fulfill orders

Schrage earned a degree in eco- for restaurants, hotels, corporate events, nomics and Asian studies from the and individuals—all before heading to University of Pennsylvania. Her invest- her day job. ment banking career took her from In 2014, CNN Money ran the New York to New Zealand to Hong story “Hong Kong’s Bagel Banker,” and Kong. There, she joined fellow expats seemingly overnight Schrage’s purpose in a chorus of “can’t-find-a-decent-ba- changed. She found a commercial gel-in-Hong Kong.” The closest thing kitchen and decided to go all in. Schrage found were frozen, colorless, “The fact that there were no real flat bagels—a sure sign that the dough bagels in Hong Kong was shocking,” had been rolled out by Schrage says. “It’s a machine instead of by melting pot of so many hand. There was only WHAT’S NEXT different cultures that appreciate high-quality one way to ensure a fresh, authentic Schrage is currently working on opening a Jewish deli. It will involve food. That first order I got from a top restaubagel in Hong Kong: bagels, of course, but also rant chef was key—it Schrage dusted off her smoked meats, smoked made me realize there grandfather’s recipe and made her own. fish, and a lot of Schrage’s favorite traditional Jewish foods: potato latkes, was an opportunity for a real wholesale

A lucky friend knishes, blintzes, and business out here.” who got to try one of “mom’s matzah ball soup.” For top hotels, she Schrage’s first batches began to hand roll to of homemade bagels order. The Mandarin requested three dozen for a birthday Oriental preferred larger sesame and party. Schrage obliged. poppy seed bagels, Grand Hyatt wanted

Serendipitously, the party was mini bagels, and The Peninsula wanted attended by people from Hong Kong’s pink beetroot canapé bagels for their food industry, and immediately after iconic afternoon tea. Schrage got a call from a well-known “Whatever they wanted, we did,” chef who just had to have some. More Schrage says. “The coolest part was that many of our wholesale partners called the bagels ‘Schragels’ on their menu, which helped us expand really quickly.” The media caught on, with stories in the New York Times and South China Morning Post. And in 2016, the global magazine Jetsetter named Schragels one of the top bagels in the world. Schrage now runs a wholesale factory and a thriving retail space. In the Schrage family, the bagel represents the perfect food. A circle. No beginning or end but held within a single delicious ring—echoes of hard work, good intentions, the soul of a grandfather, and a gift of nourishment to the people it feeds. “I’ve always believed in the dream,” says Schrage.

Rev. Gina Finocchiaro ’97

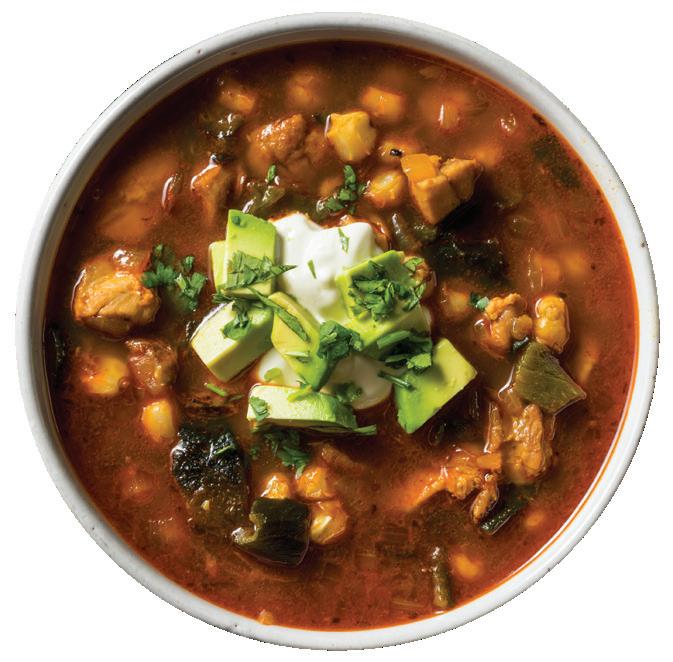

Interim Protestant Chaplain All my travel memories have a soft spot with food at the core. There was a pot of fondue with crusty bread in Québec City. The best cup of coffee with real sugar in Costa Rica, chocolate churros con chocolate in the south of Spain, fish and chips in a pub in London, pain au chocolat outside Notre Dame—and don’t even get me started about my time in Italy! Squid ink pasta on Lake Como, gelato in Florence, street food in Sicily, and cannoli from a food truck! I could go on and on. But my time in Santa Fe, New Mexico, inspired a new holiday tradition with posole. The centerpiece of Southwestern cooking is the chili pepper. I took a whole class on chili peppers when I was there. Posole is a festive colorful dish—a great recipe for days when a cook has more time as it takes a while to prepare. A pot will feed a lot of people, or last for days. In my kitchen, it is a good New Year’s Eve/Day project. It fills me with hope, sustenance, and nourishment to start the year off right. Best of all, posole is a good excuse to invite friends over!

Corrie Martin

English Instructor As years pile on living on the mainland, my trips home to Hawaii become increasingly centered around (should I admit, consumed with?) food. The moment after I click “Purchase Ticket,” a list and itinerary are produced—dishes, delicacies, restaurants, plate lunch joints, cafés, bakeries, markets, purveyors, shrimp trucks, and shave ice stands. My first stop from the airport is Tamashiro’s for poke, limu, and fresh poi. Want to hang out? Meet me at the Ramen place on King! Let’s go for a walk in Chinatown and stop for tea. I always thought the motto should not be “Lucky you live Hawaii,” but “Lucky you eat Hawaii!”

QuickBites

ISTOCK: POSOLÉ, BHOFACK2; HIBISCUS, OBSCURA99; POT, EDUARDROBERT; NAPKIN, ANDREY ELKIN

Ruth Quattlebaum P’93, ’96

Archivist Emerita

Kahlua Pie

26 chocolate wafer cookies, crushed ¼ cup butter, melted ¼ cup Kahlua 1 pint marshmallow creme 2 cups whipping cream, whipped stiff

Butter a 9-inch springform pan. Combine crushed wafers and melted butter. Press in bottom and up sides of pan, reserving enough for sprinkling on top.

Gradually stir Kahlua into marshmallow creme. Pour into pan and top with reserved crumbs

Put in freezer for 3 hours and bring directly to the table to serve.

Jennifer Savino P’21, ’24 Director of Alumni Engagement Food means family to me. Since I was a child, family dinners are every night. The people at the table are family, whether by blood or by choice. If you have sat at a family dinner table with me, you are part of my family. Family meals can take place in our home, at the beach, on vacation, anywhere in the world. The value of family dinner was instilled in me by my dad. It is a priority. It is a valued and sacred space. Food always tastes best when you are enjoying it in the company of family.

Lou Bernieri P’96, ’10

Director of Andover Bread Loaf, English Instructor My favorite food memory is of my grandmother’s pesto gnocchi— everything made from scratch with fresh ingredients—topped with Parmigiano-Reggiano.

Living Lives of Distinction

A financial services trailblazer and philanthropist. An awardwinning filmmaker and entrepreneur. A master chef and advocate.

Chosen by a seven-member alumni committee, the recipients of Andover’s Alumni Award of Distinction represent a diverse sampling of individuals and industries. While William M. Lewis Jr. ’74, Dorothy Tod ’60, and Ming Tsai ’82, P’18, have chosen different paths, these three alumni are united in their quest for excellence and their embodiment of Andover’s non sibi motto.

With more than four decades of Wall Street experience, Bill Lewis recently joined Apollo Global Management Inc. as a senior partner and member of Apollo’s executive committee.

Lewis graduated from Harvard College and earned an MBA at Harvard Business School before joining Morgan Stanley in 1982. In 1989, he became the firm’s first African American managing director. He joined Lazard Ltd in 2004, where he worked for 17 years and became chairman of Investment Banking.

Born in Richmond, Virginia, Lewis came to Andover through A Better Chance (ABC), a program whose mission is to “increase substantially the number of well-educated young people of color who are capable of assuming positions of responsibility and leadership in American society.”

Lewis went on to become ABC’s national chair, a leader in promoting advancement through educational opportunity, and a strong backer of institutions that

JESSIE WALLNER support youth of color.

Lewis is currently on the boards of several education and nonprofit institutions, including Uncommon Schools, The Posse Foundation, and City Fund. He served as a Phillips Academy charter trustee twice. In the early 2000s, he and his wife, Carol Sutton Lewis, established the African American Art Acquisition Fund, which has helped the Addison Gallery purchase 30 significant works of art to date.

William M. Lewis Jr. ’74

An award-winning film editor, producer, and director, Dorothy Tod is well known for her work on children’s television programs as well as compelling documentaries that shed light on timely social and environmental issues.

After graduating from Abbot Academy, Tod earned a BA at Vassar College. She began her film career editing footage for CBS’s Captain Kangaroo and PBS’s groundbreaking Sesame Street

Dorothy Tod ’60

LYNN HAYES and has since produced and edited more than 300 short nature films. In 1972, she established Dorothy Tod Films. What if You Couldn’t Read?, her 1980 documentary, won the duPont–Columbia Citation in Broadcast Journalism. Her 1981 film Warriors’ Women, also a prize-winner, aired nationally on PBS, providing insights into the impact of the Vietnam War. In 2000, Tod produced and directed A Dyslexic Family Diary, about a mother’s 18-year struggle to get an education for her bright dyslexic son. Tod also established and managed the Vermont Women’s Cable Network.

Following a 1998 flash flood that wreaked havoc in Vermont, Tod began focusing on water problems and dams. She is currently a member of the Producer’s Committee for Freedom and Unity: The Vermont Movie, a documentary series that aims to understand Vermont’s iconoclastic spirit.

Working in his family’s restaurant sparked his initial fascination with food, but Ming Tsai’s career path to “top chef” was not a straight one. While earning a degree in mechanical engineering at Yale, he spent several summers in Paris learning to cook. Studying at Le Cordon Bleu tipped the scales. He went on to earn a master’s degree in hotel administration and hospitality from Cornell and trained under internationally acclaimed master chefs.

In 1998, Ming opened Blue Ginger, an East-meets-West fusion restaurant in Wellesley, Massachusetts. Blue Ginger received three stars from the Boston Globe and earned Tsai Esquire Magazine’s “Chef of the Year,” among many other accolades. In 2013, he opened Blue Dragon in Boston, featuring his signature East-West fusion with a twist on traditional pub classics. Tsai is also host and executive producer of Simply Ming, an Emmy Award–nominated public television cooking show now celebrating its 17th season.

After his wife, Polly, was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2017, Tsai focused on healthier vegan cooking to help fuel her recovery. His MingsBings, highprotein, gluten-free patties packed with superfoods, debuted at Fenway Park this past summer. A portion of the proceeds will benefit The DanaFarber Cancer Institute and Family Reach.

Wonder Woman

Meet the CEO-entrepreneurtech outsider-mom who transformed a failing company into a billion-dollar enterprise

BY JENNIFER MYERS

Anjali Sud ’01 oversees a global platform with 230 million users and more than 1,000 employees as the CEO of Vimeo. She wakes every day fired up for learning more and building upon that knowledge to make an impact.

“At Vimeo, we are in a fast-moving, highly competitive space,” says Sud, who has served as CEO of the video hosting and sharing service since 2017. “There are no playbooks or rules to follow, which is challenging in the best of ways. I can’t imagine getting up every day and not feeling energized by that privilege.”

Under Sud’s leadership, Vimeo—once considered YouTube’s weird and artsy cousin—spun off from its parent company IAC/InterActive Corp. in May, becoming an independent, publicly traded company with a market value of nearly $8.4 billion.

While that energy can be intoxicating, Sud is conscious not to let her work fully consume her life. She takes time for self-care by aiming to get a solid eight hours of sleep each night and to go out for solo walks on the weekends to clear her head.

She is the first to admit that no one, not even Wonder Woman, can truly balance everything successfully.

It helps you admit what you don’t know, uncover dangerous blind spots, and continuously improve. I also think it makes you more empathetic in seeking to understand others’ perspectives.” “Code may look like random lines of indecipherable letters, but once you learn how to code, you’ll be mesmerized by how fascinating it is. Each word, each line has a purpose.”

“I live in a world of perpetual tradeoffs: as a CEO, mother, wife, friend, sister, daughter, and every other facet of my relationship with the world,” Sud says. “Every day is an exercise in picking the things to lean into and the things to let go. I’ve found that by embracing these tradeoffs and being more intentional about the things I let go, I am happier and more fulfilled in my life choices.”

Sometimes, she admits, those life choices include ordering pizza from Dominos or making a beeline for the nearest Olive Garden for those addictive breadsticks—everything in moderation.

In the workplace, Sud says she and her executive team lead by modeling curiosity and empathy in their daily interactions to create a culture that empowers people to do their best work while driving positive outcomes.

“The practice of curiosity is so valuable. It helps you admit what you don’t know, uncover dangerous blind spots, and continuously improve,” she explains. “I also think it makes you more empathetic in seeking to understand others’ perspectives.”

The mark of a successful CEO, Sud adds, is someone who can admit what they do not know and give those more talented than themselves the room to work and make decisions, knowing in the end the leader is always accountable.

“This is a skill I am continuously working on,” she says.

When the COVID-19 lockdown began in March 2020 and companies sent employees home, Vimeo was suddenly faced with a demand for their software they had never experienced before. The expansion the company had been working toward under Sud’s leadership accelerated at a rapid pace.

While the onslaught stretched the company from an operational standpoint, it also validated the vison and strategy she and her team crafted.

“Suddenly every process, every line of code, every customer interaction had higher stakes,” Sud says. “It really forced us to be more disciplined and scalable in everything we do.”

Will workers ever return to their cubicles fulltime in a post-COVID America?

“Why would we?” Sud asks. “We have a ton of work to do to truly figure out hybrid and remote work, but now that we’ve experienced some of the benefits, we can’t just bury our heads in the sand.”

The lockdown forced even the most reluctant companies to realize the constraints of time and place no longer exist. When we have the technology to hold live virtual meetings with colleagues around the globe in sweatpants from the comfort of our couches, there is no need for employees to commute two hours every day or to be restricted to job opportunities in their geographic area.

“I think the smartest companies will look at the pandemic not as a blueprint for the future of work, but as an experiment rife with learnings to test and optimize from,” Sud says. “If I had a crystal ball, I think we would see that technology—and video specifically—will continue to make work more asynchronous and accessible, so that everyone across a company, regardless of their location or schedules, can learn, collaborate, and connect more easily. That has powerful implications for productivity, culture, and inclusivity.”

Sud’s ambitious vision for Vimeo is to bring the power of video to every business in the world regardless of their budget, size, or expertise.

“If I’ve done my job well, every business—from the smallest shop to the largest enterprise—will be using video, and Vimeo will be powering a more efficient, better way for all of us to communicate, collaborate, and connect at work.”

GENDER EQUITY IN AI

To many people, coding sounds tedious and complicated. Not so for Athena Rhee ’24, who describes her newly learned skill as “fascinating” and even “fun.”

In fall 2020, while taking her PA classes remotely from her home in Seoul, Rhee taught herself to code. There were frustrations and challenges, but she was motivated: “Technology has great potential for good,” says Rhee, “but I realized that many artificial intelligence [AI] systems are being developed primarily by men. If female coders don’t step up and contribute, AI will not function equitably.

“Currently, only 12 percent of machine-learning researchers are female,” she continues. “Because of this gender disparity in STEM fields, the algorithms, data sets, and designs in AIs are at risk of neglecting the challenges faced by women and other gender minority groups.”

Rhee cites the field of medicine as an example. “Treatments effective for men might not be as effective for women.” Female coders, she notes, “offer different insights, resulting in data sets and algorithms that enable AI systems to provide more accurate diagnoses and more effective treatments for women.”

This past summer, Rhee was appointed to the board of Code Your Chances (CYC), a global nonprofit that teaches young girls the importance of computer science and showcases the opportunities available by learning to code. Rhee helps CYC locate organizations to collaborate with and host interactive workshops.

A member of PA’s Computer Science Club and AI Club, Rhee shares her coding experiences and enthusiasm widely. “AI will be guiding and controlling more and more aspects of everyone’s lives in the years ahead,” she says. “A more genderinclusive creation of AI will help technology address the real-world challenges that all humans face.”

—JILL CLERKIN

Paving the Way

Louis Parker ’73 helps the next generation navigate their way to success

BY DAVID PERRY

Louis Parker remembers well the change of scenery.

His hometown, Homewood, was an area of Pittsburgh known for gun violence and hardscrabble poverty; it was all brick, tar, and concrete. In the fall of 1969, he arrived at Phillips Academy—a visual feast of trees, manicured lawns, and historic halls.

But it wasn’t just the landscape. Parker, who came to PA through A Better Chance (ABC)—a nonprofit that pairs students of color with quality educational opportunities—was a young African American in a sea of white faces.

“By the time I arrived, ABC had really begun to change the population. There were 40 or 50 other students of color,” recalls Parker, adding that he arrived just a few years after his older brother, John, who was one of ABC’s first students in 1965. “The school I went to in Homewood had 2,000 students, and two of them were white.”

After graduating in 1973, Parker earned a BA in political science from the University of Pennsylvania in 1977 and an MBA from Harvard Business School in 1990. He then blazed a trail across the boardrooms of America, corporations that need only initials: notably, IBM, ADP, and GE. At General Electric, he rose quickly to become one of the corporation’s top 40 executives.

He now sits on the board of A Better Chance.

In 2011, Parker decided to concentrate on giving back to Black and Latino youth and, in 2013, he opened the public charter school Visible Men Academy (VMA) in Bradenton, Florida, to battle what he calls “the humanitarian crisis of education for boys of color.”

Recently, Parker left the corporate world to become VMA’s CEO. He made some changes, brought in fresh personnel, and bore down full-time on fleshing out his vision of a school that would eventually make today’s good students tomorrow’s good men.

The school, which is tuition-free, currently has 100 students, kindergarten through grade five.

“There is a crisis of Black and brown boys and a huge dropout rate,” says Parker. “Changing that is our mission.”

Education, he adds, is the key to making better partners, citizens, and employees.

“I was just like these boys,” he explains, “but there wasn’t an opportunity at the time for people like me in K–5— years that are very formative.”

Parker wishes his Alabama-born father had such an opportunity. Born on a farm, he came back from World War II and worked for the Pennsylvania Railroad, though he never learned to read or write. When he took a test to earn a higher license with the company, he had to ask to bring his wife in with him so she could read the questions.

“I thought I had a great childhood,” says Parker, who has a 15-year-old son. “I was a good student. I knew we weren’t rich, but I didn’t know I was living in poverty until I went to Andover. When I was doing well in corporate America, people would say, ‘you are living the dream!’ But I didn’t have that dream. As a kid, I didn’t know it even existed.”

In addition to academics, the students at VMA—thanks to Parker’s experience and leadership—are receiving an early childhood education that is strongly rooted in emotional health— focusing on character, relationships, and belonging.

Andover, he says, “taught me how to learn. I had done well in school before, but Andover was different. I had to learn how to learn and mature. At 14, being so far from home after growing up in an all-Black community was a big difference. When I got to Andover, I was so homesick. But after a semester I didn’t want to go home.

“Andover taught me who I am. It gave me the ability to navigate through society and to stand toe to toe with anyone.”

MANUEL A. “MANOLO” CADENAS ’40 recently joined the exclusive centenarian club and is the author of Memories of a Journey Through Time, an autobiography about his early life in Cuba and the difficult period of the 1960s when he, his wife, and three young children left behind all their material possessions to seek freedom in America.

UNEXPECTED ART

JENNIFER CECERE ’69

Thousands of people hustle through the Little Italy–University Circle railway station in Cleveland every year. All pass under a suspended intricate sculpture that might remind some of the handmade white doilies adorning side tables at Nona’s house. Some may be surprised to find a 15-foot-long sculpture of five interlocking white lacy domes made of laser-cut steel casting intricate shadows on the tile station walls.

“The goal for the piece is to champion the handiwork of unsung women. I love the idea of taking activities like knitting and crochet, often considered safe outlets for women done alone in private, into the public realm,” explains Jennifer Cecere, who won a national competition to create the permanent public art work. “The view is a little bit unexpected. You’re in a public space being confronted with materials and processes that you don’t expect to see. It’s meant to challenge our notions of public art.”

Cecere grew up in Richmond, Indiana, as a 4-H girl and a daughter of Italian-American parents. She became interested in art at a young age, studied art with Ginny Carter and photography with Wendy Snyder MacNeil at Abbot, and earned a BFA at Cornell University.

For more than 40 years, Cecere has created large public sculptures, such as Double Doily—a white bench featuring a lace pattern made of aluminum (see below)—and other pieces made of plastic, vinyl, and fabric. Her work has been exhibited in sculpture parks, galleries, and museums, including Central Park, the Staten Island Ferry Terminal, Newport Beach Sculpture Park, the Guggenheim Museum, MoMA/PS1, Smithsonian Museum, and the Addison Gallery of American Art.

—NANCY HITCHCOCK

KNOWLEDGE & GOODNESS: THE ANDOVER CAMPAIGN

Big Blue Connections

Finding resonance in reunion giving

Reunion, whether in person or virtual, presents a unique chance to reconvene, reminisce, and create new Andover moments. For alumni celebrating these milestones, reunion also provides an opportunity to make a singular impact at Andover— one that lasts long after Reunion Weekend has ended.

In fact, every year, more than 1,500 donors across 21 classes unite to pair their personal and class affinities to Knowledge & Goodness priorities, such as scholarships, campus enhancements, Outreach programs, and other key areas.

For alumni Amy ’98 and Peter Christodoulo ’98, making a gift to mark their 20th Reunion was a natural way to commemorate their own time at Andover. Twenty years after Commencement, through college, careers, and parenthood, they’ve never forgotten the place where they met, the place that Peter still calls “home.”

Recently, the couple named a locker room in the Snyder Center with their first major gift, a tax-smart donation of appreciated securities.

“A lot of things aligned—our reunion, the campaign, and our resources. I thought, we can make this an especially meaningful show of support,” says Peter, who played squash and tennis as a student. “We wanted to demonstrate our enthusiasm for the Academy and what it’s meant to us, and our reunion was a good chance to do that.” “When we made this gift we were kind of new to philanthropy,” Amy adds. “We didn’t come from families that gave in big ways, so it wasn’t like this was a well-established thing that we did. But I always wanted to help today’s students have the same kind of transformative experience we had. When I think about our formative years and the impact that the Academy had, I will always be grateful.” The Class of 1971 was also prompted by gratitude—and non sibi spirit—GIL TALBOT for their 50th Reunion gift. A dozen classmates collab-

GIL TALBOT

BETHANY VERSOY

orated to match any donations from the rest of the class to Andover Bread Loaf and PALS, two longstanding Academy Outreach programs. The chosen recipients of the match funds were the nonprofits Groundwork Lawrence and Habitat for Humanity, in recognition of the decades-long partnership the school has enjoyed with the greater Merrimack Valley community. Additionally, a state tax credit awarded to some of the donors will be re-donated. The unique endeavor—christened the PA’71/Lawrence Project—proved popular, pushing total class reunion participation to 41 percent. Many volunteered their time for Andover as well.

“Most of us had been struck by the state of the world and COVID-19 and Every year, more than 1,500 donors across 21 classes unite to pair their personal and class affinities to Knowledge & Goodness priorities, such as scholarships, campus enhancements, Outreach programs, and other key areas.

its impact on the economy,” says Geoff Foisie ’71. “I asked, what if we use this occasion—reunion—as a way to assist those who are less fortunate. And class members responded right away.”

The gift resonated with a class that attended Andover during an era of increased social consciousness. “This was really a group initiative, and that was one of the great things about it,” he says.

Likewise, the Class of 1966 banded together for its recent reunion effort. Galvanized by the leadership donation of Chris “Topper” Lynn ’66 to fund the pool in the highly anticipated Pan Athletic Center, the class successfully launched a series of giving challenges aimed at facility enhancements and financial aid.

“Topper’s gift caught the imagination of our class, and we went from there,” says Robin Hogen ’66, who works to build alumni participation as head class agent. “Everyone we asked to contribute said, yes, I’m in, I want to do this.”

In an impressive flurry of generosity, the class named the boys’ locker room and hot tub in the future Pan Athletic Center, and endowed two scholarships, all in tribute to much-loved and admired classmates. Donors hope the funding helps keep Andover athletes competitive and boosts educational resources for current and future students. According to Hogen, the Class of 1966 is exploring additional avenues for impact.

“Who knows what the next five years will bring?” he says, given that gifts made in the five-year reunion cycle— ending in Reunion Weekend—count toward class giving and participation goals. “There’s plenty of opportunity for alumni to join in.”

TORY WESNOFSKE

To learn more about reunion giving, please contact Nicole Cherubini, director of development, at 978-749-4288 or ncherubini@andover.edu.

Transforming Our Investment in Health Care

BY VANESSA KERRY, MD, MSC, ’95

As a physician I have worked in myriad settings. I have had the privilege to train in some of the world’s top hospitals, serve in urban community health centers, deliver care in rural Africa, work overnights in post-earthquake Haiti, and swelter in PPE in the trenches of COVID-19. Each of these experiences has cemented my deep understanding that health care is fundamentally human-centered. Doctors, nurses, midwives, and health workers of all types serve as the front lines of human response in sickness. And at the center is the patient who is a wife, a father, a child—a human life in need, with a community that revolves around them.

Thus, when World Health Organization Director General Dr. Tedros Ghebreyesus shared in May that more than 115,000 health-care workers had died due to COVID-19, I was stunned. Though paling in comparison to the millions of lives COVID-19 has taken in total, these workers’ deaths are significant. Collectively, they represent a loss of over one million years of education, $4.5 billion in training, and a devastating blow to a sector already facing personnel shortages estimated to reach 18 million people by 2030. The immediate impact is that more people, especially in communities that need it the most, will lack access to health services.

As we respond to COVID-19, we will need to acknowledge and act in support of the profound role of health workers far more than we have to date. In recent years, the promise of technology in global health has drawn massive speculative dollars and attention. Financiers, philanthropists, and governments have intensified their investments in health care research and infrastructure. Interventions have made progress in some disease areas like HIV. However, support for the front lines of health delivery—the workforce—has not kept pace, and impact has remained siloed and underleveraged. The lack of prescriptive policies or funding to invest in the workforce are telling, reflecting a persistent misunderstanding of the essential role of health workers in ensuring health for all.

The global COVID-19 vaccine rollout offers a poignant example. The need for vaccines is without question, but health workers are critical to delivering shots in arms and protecting essential services. Independent reports have indicated that for every $1 invested in vaccine supply, $2.50 would be needed to deliver vaccines to patients. Yet, while governments wrestle with their vaccine donations to COVID-19 Donations Global Access (COVAX), none have committed to the essential human resources needed to deliver them. As a result, many countries remain unprepared: vaccine readiness in at least 11 African countries is at 75 percent or less.

The pandemic has rolled back decades of progress, tested the resilience of health systems, and unmasked continued inequities across the globe. Recent studies have shown increases in maternal mortality and tuberculosis deaths, for example, since COVID-19 began. The World Bank has estimated the cumulative cost of COVID-19 to be more than $16 trillion to date. In contrast, researchers have estimated the cost to achieve necessary and overdue global benchmarks in health, including universal health care and filling the global shortages of health workers, to be a fraction of that figure. At $400 billion, the annual investment required to close the gap is one-fortieth of the cost of COVID-19 and promises dividends in development, economic growth, and well-being, beyond those of health.

While the investment is significant, evidence shows that growth of the health sector and health system improvements have sizable returns. Macroeconomic analysis has indicated that 25 percent of economic growth in low- and middle-income countries from 2000 to 2011 was attributed to improvements in population health. Additionally, investing in health systems has multiplier effects. It improves health, strengthens

economic growth and national security, and fosters greater social protection and cohesion. The health and social sectors generate jobs, almost 70 percent of which will be occupied by women. The employment of women achieves progress toward both gender equality and poverty alleviation and brings families into the formal sector.

I have seen this transformation firsthand in my work at Seed Global Health, the international non-governmental organization I run. At Seed, we focus on the power of investing in health and the health workforce to transform countries. Through partnerships with sub-Saharan African governments and in-country academic institutions, we have helped train more than 30,000 doctors, nurses, and midwives over the past nine years and have impacted hundreds of thousands of lives. Today, these are the same health workers who have been on the frontlines of the pandemic, responding to COVID-19 and protecting essential services—the tuberculosis cases and deliveries that are otherwise on the rise. Our model leverages education over time to help provide better care to patients, train future generations, support the health sector, and catalyze change in the health system. Though it has taken a decade, we can see the progress in closing the unacceptable gaps in health care that not only exist, but also are now expanding.

COVID-19 has underscored the importance of health as essential for social well-being, economic growth, and equity and for resilient communities and countries. It has shown us we must meet health challenges directly—newly emerged or entrenched.

As we seek to define and enact “pandemic preparedness” or to “build back better,” we must transform our priorities in health and our approach to health investments. Otherwise, we will only cement our status quo, and the global health system—and all its impacts—will continue to operate as it always has.

The world has the capacity—tools, science, technology, financial mechanisms—needed. We must now summon the political will and courage to redeploy these resources more effectively for systemic transformation. It starts by investing in and valuing people, our own futures, and those health workers who protect them.

ISTOCK: WANLEE PRACHYAPANAPRAI

Vanessa Bradford Kerry is founder and CEO of the nonprofit Seed Global Health, which focuses on the power of investing in health and the health workforce for social well-being, economic growth, and equity to transform countries. She is also a critical care physician at Massachusetts General Hospital, serves as the associate director of partnerships and global initiatives at MGH Global Health, and directs the Global Public Policy and Social Change program at Harvard Medical School. Kerry recently lent her expertise to Andover’s health advisory board to help the Academy navigate the COVID-19 pandemic.

LOOKING BACK ON CLASS NOTES

REMEMBERING 9/11

Normally, Class Notes capture important life transitions: weddings and births, degrees earned, careers charted. Social get-togethers and Andover/ Abbot memories are reliable staples, too, as are, especially in older classes, obituaries, and fond farewells.

Occasionally, though, a singular event triggers reactions from all corners of the PA community. Then “normal” no longer applies. Such was the case 20 years ago following the 9/11 terrorist attacks, when this magazine published a special

September 11 Reflections issue.

Of the 100 Class Notes columns published that winter, nearly half made reference to 9/11. Many entries were intensely personal, particularly from alumni living or working near the attack sites.

The first came via Jim Carrington ’42, who shared news of his grandson’s “miraculous” escape from the World Trade

Center. From John Li ’50, a Brooklyn hospital physician: “So many blood donations were collected from people who waited in long lines for hours, more than could be used,” he wrote, in true non sibi spirit. More than ever, he concluded, “We have to help the world.”

Martha Belknap ’54 posted similar sentiments. “May we continue to pray for light and love to enter the hearts and minds of everyone so that peace will prevail in our world.” Edie Williamson Kean ’54, already volunteering at Ground

Zero, observed, “It helps to have some tiny part in the cleanup.” Jennifer Cecere ’69 wrote that while New York City was slowly healing, there remained a “big sadness,” inspiring her to join a group committed to rebuilding Lower Manhattan.

Sven Hsia ’59 had watched the South Tower collapse from his office window. “A greyish cloud of debris came rumbling down Wall Street with the full force and effect of a flash flood roaring down a narrow canyon passage,” he recalled. Weeks later, he could still smell the acrid smoke. From her office in Queens, Sara Ingram ’71 also witnessed the towers aflame. “Someone walked by, looked out the window, and asked if they were filming a movie—that’s how unreal it looked,” she posted. Closer to campus, John Doherty ’59, director of Veterans Services for the Town of Andover, wrote of supplying PA with American flags for a campus candlelight service.

Another eyewitness, Julian Hatton ’74, had stared through a rooftop telescope at a woman trapped in the blown-out tower, waving for help. And then, “I turn to see Tower 2 snapping at the level where the hole was,” he wrote. “I don’t remember hearing the roar and tear of steel; it’s as if the spectacle was encased in a silent cocoon.” Robert Preston ’74 reflected upon the emotional impact of the shrines—teddy bears and love letters—he’d seen to victims still missing or presumed dead.

Alex Belida ’66 had been headed to his Pentagon office when the hijacked plane struck. Two days later, he visited the impact site, “which by then was filled with thousands of FBI, troops and rescue-fire workers,” he reported, comparing the scene to others he’d witnessed in war-torn Africa. “It’s a shame,” he added, “it took these horrific events to focus our government and people on a plague that has ravaged other countries for years.” CNN newsman David Ensor ’69 echoed that theme, writing, “Many Americans did not understand how interdependent they really are with the rest of the world.”

The longest entry, from John Ketterer ’82, was a harrowing narrative of searching for a friend in the smokey chaos near Ground Zero. Miraculously, the two found themselves side-by-side in an adjoining plaza, ash-covered and barely recognizable to each other.

The sense of loss expressed by friends of Todd Isaac ’90 and Stacey Sanders ’94 was particularly sharp. “Todd modeled for us all the beauty and importance of being yourself and reaching out to share your positive spirit with everybody,” penned Louise Parsons ’90. Within two days of the attacks, wrote Moacir de Sa Pereira ’94, the class e-mail list was flooded with posts as “it became clear that we’d lost a classmate, something for which no one is ever prepared.”

Threaded throughout was a message perhaps best expressed by ’83 columnists Elizabeth McHenry and Electa Sevier: “Our hearts go out to all who have lost loved ones,” they wrote. “We hope that the news we report here will inspire you to contact old pals and renew bonds of friendship that are so central to our happiness and well-being.” Those Andover bonds had rarely seemed more important. Or more durable.

—JOE KAHN ’67

Déjà Blue offers snapshots of alumni letters and Class Notes from Abbot and PA archives, thanks to the Class Secretaries Committee.

Food for Thought

BY ALI ROSEN ’03

Idon’t know how to get people to agree on politics or money or religion. But start talking about food, and I can get your entire life story.

I always wanted to be a storyteller—at Andover I wrote for The Phillipian and directed theatre—but no arena inspired me the way food does.

Food is our childhoods, our cultures, our celebrations, and our comfort in trying times. It is one of the few mediums in which you can tell a story through every one of the senses.

I always felt this way about food, but I never thought I could actually make it into a career. My path to food as a profession was a circuitous one. I interned and worked in restaurants and wrote recipes when I was younger, but I never saw it as a serious option that I could pursue professionally. After graduating from college, I started working in news production. But a few years in, I had a sit-down with a correspondent who passionately advised me to follow my dreams by following the story. He, of course, was referencing his years in far-flung bureaus, doggedly pursuing whatever was behind the international headlines. But it planted the seed that my storytelling passions might lie elsewhere.

I took a leap and went to work for a food website startup. It was a risk, but one that I could not have been happier with once I got to spend my days in kitchens, learning from chefs about their most beloved dishes.

I eventually landed my own show, Potluck with Ali Rosen, telling the stories of chefs, restaurateurs, farmers, and makers around New York City and across the globe. I’ve been lucky to interview some of the greats like Anthony Bourdain, Jacques Pepin, and Martha Stewart. But I have so much more enjoyed the opportunity to share the stories of people whose food hasn’t garnered as much attention.

I’ve watched thousands of dumplings being made for the dim sum brunch rush and gone behind the scenes of a generations-old matzoh factory. I’ve gone to salmon hatcheries in Alaska and whiskey distilleries in Japan. And the best part of my job is that whenever I want to learn a recipe, I not only get to ask the best chef how to do it, but

NOAH FECKS

also get to share their intimate knowledge with viewers who want to know. In turn, I’ve been able to take my knowledge and help others become more confident cooks through my show and cookbooks.

Covering food professionally means a lifetime of education. There is no such thing as full expertise on food. You can spend years studying one niche topic and still learn every day. You can meet the world’s foremost expert in the foods of a specific region or of a particular type of baking and yet there is still a hunger to know more. There always is more. And at the end of that exploration there is always a literal treat. What career could possibly be better?

Ali Rosen ’03 is an Emmy Award- and James Beard Award-nominated food writer and TV host. Her show, Potluck with Ali Rosen, is in its 13th season on NYC Life. Rosen is the author of two cookbooks: Bring It: Tried and True Recipes for Potlucks and Casual Entertaining and Modern Freezer Meals: Simple Recipes to Cook Now and Freeze for Later. Follow her on Instagram @ali_rosen

JUNE 28–JULY 31, 2022

Give your child the gift of an Andover Summer experience

Phillips Academy’s Summer Session is seeking talented, motivated students to join our

2022 cohort. More than 500 students from the United States and abroad enjoyed a safe and successful return to Summer Session on the Phillips Academy campus in 2021, sharing a transformational five-week academic experience they needed after a challenging year. This coming summer, our flagship program for rising 7th- through 12th-graders will offer a variety of exciting new courses—including Entrepreneurship, Neuropsychology, and Art as Action—as well as old favorites like Writing for Success, CSI: Andover, and Applied Physics. In addition, our new 9th-Grade Academy will offer students an interdisciplinary course designed to prepare them for the unique transition from middle to high school.

From in-person to online, Phillips Academy offers something for everyone in summer 2022.

at Andover, MA and additional mailing offices

A Hoppin’ Good Show

More than 1,200 guests attended Family Weekend in October, marking an in-person return to this important annual event. In addition to enjoying concerts by the

Academy bands and orchestras, families also had a chance to watch Andover’s student talent show, Grasshopper Night. For more photos, visit

phillipsacademy.

smugmug.com.