The Murillo Bulletin

About PHIMCOS

The Philippine Map Collectors Society (PHIMCOS) was established in 2007 in Manila as the first club for collectors of antique maps and prints in the Philippines. Membership of the Society, which has grown to a current total of 42 individual members, 8 joint members, and 2 corporate members (with two nominees each), is open to anyone interested in collecting, analysing or appreciating historical maps, charts, prints, paintings, photographs, postcards and books of the Philippines.

PHIMCOS holds regular meetings at which members and their guests discuss cartographic news and give after-dinner presentations on topics such as maps of particular interest, famous cartographers, the mapping and history of the Philippines, or the lives of prominent Filipino collectors and artists The Society also arranges and sponsors webinars on similar topics. The talks are recorded and can be accessed by members through our website. A major focus for PHIMCOS is the sponsorship of exhibitions, lectures and other events designed to educate the public about the importance of cartography as a way of learning both the geography and the history of the Philippines. The Murillo Bulletin, the Society’s journal, is normally published twice a year, and copies are made available to the public on our website.

PHIMCOS welcomes new members. The annual fees, application procedures, and additional information on PHIMCOS are available on our website: www.phimcos.org

Front Cover: Detail of the Philippines from the ‘Spice Map’ by Petrus Plancius, first state, Amsterdam, c.1594 (image courtesy of León Gallery, Manila)

1

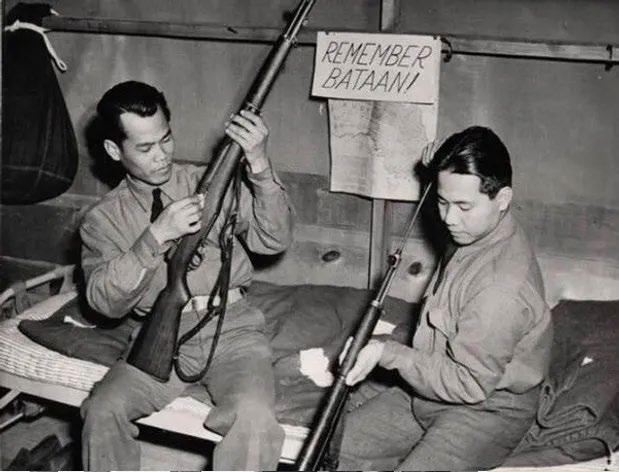

Issue No. 17 May 2024 In this issue PHIMCOS News & Events page 3 Our Cover: The Petrus Plancius Spice Map 7 How PHIMCOS was Founded by Mariano Cacho Jr. & Rudolf J.H. Lietz 9 Proposed Development Plan of the City of Cebu and Vicinity by Margarita V. Binamira 11 Mapping Peoples and Places by Mark Dizon 16 Alexander Dalrymple's ‘Chart of the Philipinas’ by Peter Geldart 23 Dauntless: book review by John L. Silva 33 Searching for Billie: book review by Jonathan Wattis 37 PHIMCOS Trustees, Members & Committee Members 40

PHIMCOS News & Events

ARRANGED by Jimmie González through his contacts in the Lion City, PHIMCOS events for last year culminated in a three-day visit to Singapore to attend the formal opening at the Asian Civilisations Museum (ACM) of the exhibition Manila Galleon ‒ From Asia to the Americas on 15 November, 2023. All PHIMCOS members had been invited, and more than a dozen of us (including relatives and friends) were able to join the events

The previous evening Dr. Melanie Chew, a former member of the ACM board, hosted a dinner to introduce us to Mark Lee, CEO of the Sing Lun Group and the current ACM Chairman, and Kennie Ting, Director of the ACM and the Peranakan Museum. They explained how the exhibition was visualised and planned, how long it took for the exhibits to arrive, and the implementation of the final preparations. From conception to execution, it was a journey of almost five years!

The Manila Galleon exhibition, which ran from 16 November, 2023 to 17 March, 2024, explored the trade that connected Asia to the Americas and then to Europe. Ships laden with porcelain, silk, spices and other goods sailed

annually from Manila to Acapulco, returning with millions of pieces of silver. Featuring over 140 extraordinary works of art from the 16th to the 20th centuries, the exhibition revealed how people, goods and ideas circulating through the Philippines and Mexico created a distinctive, shared cultural and artistic heritage. Looking at Manila as a precursor of Singapore, it reflected the unique qualities of Singapore’s own blended society and the important role port cities have played in trade and the cultural exchanges that shaped the world.

On the morning of 15 November we were treated to a preview of the exhibition led by Kennie Ting, Clement Onn, Deputy Director and Principal Curator, and Nor Wang, Assistant Director for Development. We are grateful to all of them for taking time out of their incredibly busy schedules to give us a private viewing of the exhibits.

In the first-floor foyer we admired the towering, five-metre Tree of Life created by the ACM in partnership with Lidia Riveros, an independent curator who specialises in Mexican culture and folk arts The tree of life, an ancient symbol used by cultures from all around the world, illustrates

3

Kennie Ting, Director, ACM (seventh from right) and colleagues from the ACM, with Jimmie and Connie González and other members of the PHIMCOS delegation on 15 November, 2023

relationships between ancestors, parents and descendants. The installation, featuring trade goods and photographs of people of African, Chinese, Filipino, Mexican and Spanish descent, took inspiration from the family trees of the mestizo communities that developed as a result of the Manila Galleon trade.

The various items and artifacts on display came not only from the ACM; many were on loan from various private collectors and museums in Mexico, Peru, the Philippines, Singapore and Spain. Highlights included the 1734 Murillo Velarde Map from the Fernando and Catherine Zobel de Ayala Collection; a gold chalice and a silver casket, both 17th century and adorned with precious and semi-precious stones, from the San Agustin Museum in Intramuros; preHispanic gold ornaments from the Ayala Museum and private collections in the Philippines; and (for many of us the pièce de résistance) the famous c.1650 wooden arcón (chest) with a view of Manila painted in its lid, from the Museo de Arte José Luis Bello y González in Puebla, Mexico. In the foreground of the view Chinese officials and merchants are depicted in the Parian, including some on horseback, implying their high status in Manila at that time.

That evening the exhibition was formally opened by the guest of honour, Hon. Alvin Tan Sheng Hui, Singapore’s Minister of State for Culture, Community and Youth and Minister of State for Trade and Industry. H.E. Agustín García-López Loaeza, Ambassador of Mexico to Singapore, and H.E. Medardo G. Macaraig, Ambassador of the Philippines to Singapore, also gave entertaining and inspiring speeches. In his remarks, Amb. Macaraig said that everyone present was part of the exhibition, and each conversation was living proof of the Manila Galleon trade. With the champagne, wine and hot chocolate flowing, and international canapés aplenty, the audience was then entertained until late by the Yvette Atienza Latin Jazz Ensemble.

The following day PHIMCOS member Julian Candiah arranged for those of us who were available to visit the National Library of Singapore. Makeswary Periasamy, the Senior Librarian for Collections (Rare Materials), welcomed us and laid out a selection of maps

for us to view. These included rare manuscript and printed 19th century Admiralty charts of the Straits of Singapore and Singapore Harbours and Roads, and a Proposed Development Plan of the City of Cebu and Vicinity that none of us had seen before (see page 11).

Makeswary Periasamy, Senior Librarian, and PHIMCOS members at the National Library of Singapore on 16 November, 2023

On 21 February PHIMCOS held its Annual General Meeting. The meeting, the first of the year, was attended by a record number of people: 24 members and 16 guests came in person, and 4 members and 5 guests joined us via Zoom. The atmosphere recalled our earlier meetings before the Covid pandemic. As it was the AGM, proceedings started with Jimmie González delivering his President’s Report. The past year was an active and successful one for the Society, with five presentations and a live demonstration; invitations to attend events at the Instituto Cervantes in Manila, the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. and the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore; the approval of amendments to our by-laws; continued growth in our membership; and healthy finances.

Jimmie reported that the Board has approved the designation of Nito Cacho as Chairman Emeritus, in recognition of his role as one of the founding members of PHIMCOS and our first President. Nito has been a critical adviser for our activities and in the early days was the indefatigable host to many meetings in his home. Under his leadership Nito has seen PHIMCOS grow from the group of 14 founding members (including the five board members) in

4

2007 (see page 9) to today’s society with its total of 62 members / nominees located in six countries. Our meetings, exhibitions, presentations, webinars and publications have been complimented both locally and internationally.

With his new designation, Nito has retired as a member of the Board of Trustees, and Miko David has been elected to the vacated seat. Miko has been a member of PHIMCOS since 2019 and is the President of David & Golyat, a digital strategy consulting firm based in Manila As an active member of the Communications Committee, he is helping us to improve our website, enhance our communications platform to ensure our members’ data privacy, and expand our contacts with potential new members through social media.

After the formal AGM proceedings and dinner, the meeting enjoyed two presentations. The first was ‘Mapping the Sarangani Islands’ by Ian Christopher B. Alfonso, who is the Supervising History Researcher and Officer-in-Charge of the Research, Publication, and Heraldry Division of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP). His books A History of the Sarangani Islands 1521-1921 and Dogs in Philippine History were available for members to purchase.

The Sarangani Islands, now part of the province of Davao Occidental, were among the earliest parts of the Philippines to be mapped as they were visited by the Magellan-Elcano expedition in 1521. They were subject to a centuries-long tug-of-war between the Spanish, the Dutch, the Portuguese, the Maguindanao Sultanate, and the regional inhabitants of the Sangihe islands. Alfonso explained that when Spain finally took control of Sarangani in the 19th century the local Blaan place names were adopted (see map on back cover).

In the second presentation, Ian Gill gave a highly-entertaining talk about the history of three generations of his Anglo-Chinese family in China, Hong Kong, New Zealand, the Philippines and England, as recounted in his newlypublished book Searching for Billie. The book (which was also available for members to buy) is a deeply personal memoir of the bonds between the author’s family and their crosscultural experiences, set against the background

of China’s most turbulent century His mother Billie, who was Chinese but was raised as a Eurasian, embarked on a journey through life shaped by the dramatic history of China in the 20th century. For better and for worse, Billie found that she belonged to both the Chinese and the European worlds.

After covering the story of the hotel in Chefoo owned by his great-grandparents, and his grandfather’s peripatetic career with the Imperial Maritime Customs and the China Post Office, Gill gave an animated account of his mother’s eventful life, including her adoption in Changsha; work as a popular radio broadcaster in wartime Shanghai; tragedy and a doomed romance in Stanley POW internment camp in Hong Kong; an unsuccessful attempt to set up a United Nations agency in Manila; receipt of an MBE from the Queen at Buckingham Palace; and a successful career with the U.N. in Geneva.

On 13 February, PHIMCOS members were invited by Andoni Aboitiz, in his capacity as Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the National Museum of the Philippines, to the official ceremony for the turnover by Edwin and Aileen Bautista to the museum of their gift of four early-19th century panels depicting the founder of the Augustinian Order. The panels, which feature the image of St. Augustine of Hippo, were originally on the pulpit of the Patrocinio de Maria Santisima Parish Church in Boljoon, Cebu.

PHIMCOS members were also invited, by the Spanish Embassy and the Instituto Cervantes, to the opening on 14 March of the exhibition ‘Four Centuries of Spanish Engineering Overseas’ at the Museo San Agustin in Intramuros.

Another invitation was extended to PHIMCOS members by Léon Gallery, to attend a preview on 19 March of the ‘Passion and Compassion’ Lao Lianben Collection of Dr. Leovino Ma. Garcia. Lao Lianben is a Filipino visual artist known for his minimalist, often abstract, works inspired by poetry and words. He uses found objects and indigenous materials to create unique textures and patterns, and his works are commonly associated with the spirit and aesthetics of the Zen.

5

London 4 Bury Street, St James’s London SW1Y 6AB +44 (0)20 7042 0240 New York PO Box 329, Larchmont NY 10538-2945, USA +1 (212) 602 1779 Daniel Crouch Rare Books info@crouchrarebooks.com crouchrarebooks.com

SCHENK, Petrus. Nova totius Asiae tabula. Amsterdam, [c1710].

Our Cover

The Petrus Plancius ‘Spice Map’

OUR COVER shows a detail of the Philippines from a rare first state of the celebrated map known as the ’Spice Map‘, produced by the Dutch mapmaker Petrus Plancius in c.1594. The map, from the early years of the so-called Golden Age of Dutch cartography, marks an important development in the Western mapping of Asia.

Having declared its independence from the dominant Spanish empire in 1581, the up-andcoming Dutch Republic wanted to muscle in on the riches of the Far East, in particular the allimportant trade in spices with the eponymous Spice Islands. To access this great source of wealth, the Dutch navigators and traders needed maps to chart the fastest, safest course for their ships sailing to Asia, and to protect their precious cargos. In an early case of commercial espionage, Amsterdam was able to acquire Portuguese and Spanish maps, which were then copied by Dutch cartographers.

This map, which shows all of Southeast Asia from Siam and the coast of Vietnam in the west to the Solomon Islands in the east, was a huge improvement on previous printed maps of Southeast Asia. In the Philippines, Luzon and Mindanao are well-drawn, although the Visayan islands are less accurate. Panay is named ‘Panama’, Negros ‘Negoes’, Cebu ‘Cabu’ and Leyte ‘Sabura’. An enlarged Palawan is confused with the Calamianes group of small islands to its east. To the southeast a vast New Guinea is tentatively shown as part of the theoretical ‘southern continent’. The map is one of the first to show ‘Beach’ (at bottom-left), the tip of the continent to be later known as Australia.

The map, which measures 38 cm x 55 cm, has been described as ‘the most famous, most important, most beautiful, most wanted and one of the rarest of all maps of Southeast Asia’. It is known as the ‘Spice Map’ because of the drawings at the bottom of nutmeg (Nux Myristica), cloves (Caryophilorum Arbor) and three colours of sandalwood: yellow (Santalum flauum), red (Santalu rubrum) and white (Santalum album).

The full title of the map is: INSULAE MOLUCCAE celeberrimæ sunt ob Maximam aromatum copiam quam per totum terrarum orbem mittunt: harum præcipuæ sunt Ternate, Tidoris, Motir, Machian & Bachian, his quidam adjungunt Gilolum, Celebiam, Borneonem, Amboinum & Bandam. Ex Insula Timore in Europam advehuntur Santala rubea et alba, Ex Banda nuces myrysticæ, cum Flore, vulgo dicto, Macis, Et ex Moluccis Caryophilli : quorem icones in pede hujus tabellæ ad vivum expressas poni curavimus. This can be translated as follows:

“The islands of the Moluccas are very famous because of their extremely great wealth in spices, which they export over the whole world. The most important islands are Ternate, Tidor, Motir, Machian and Bachian. Some would expand this list to include: Gilolo, Celebes, Borneo, Ambon, and Banda. From the island of Timor, red and white sandalwood is shipped to Europe, from Banda nuts with their flowers commonly named mace, and from the Moluccas cloves. At the foot of this map, we have arranged to include pictures of these products drawn from nature.”

The Flemish-Dutch mapmaker Petrus Plancius (1552-1622) was an astronomer and cartographer who was also a minister in the Calvinist Reformed Church. Plancius copied 25 confidential manuscript charts by the Portuguese cartographer Bartolomeu Lasso, obtained from Lisbon by the brothers Cornelius and Frederick Houtman. Following the successful rebellion against their Spanish overlords in 1579, the Dutch wanted a share in the lucrative trade in spices from the Far East. Plancius supported a covert mission to promote the Dutch voyages of exploration to the Spice Islands that would result in the establishment of the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC), the Dutch East India Company, in 1602.

Plancius’s Spice Map was not included in any atlases or books, but was issued separately and sold only as a loose chart. It was engraved by Joannes van Doetecum, and first published in Amsterdam by Cornelis Claesz in 1592-94.

7

The first state of the ‘Spice Map’ by Petrus Plancius, Amsterdam, c.1594 (image courtesy of León Gallery, Manila)

According to the expert Günter Schilder in his Monumenta Cartographica Neerlandica, Vol. VII (Uitgeverij Canaletto/Repro Holland, Alphen aan den Rijn, 2003) only five copies of the first state of the map were known to have survived: four in institutional collections and one, now in private hands, sold at auction in Europe in 2018. In 2023 a previously unrecorded sixth copy of the first state was discovered in the collection of the late Vilem ‘Bill’ C. Wilhelm, an American hydroelectric engineer who worked in the Philippines on projects for the World Bank. He collected maps in the 1970s and 1980s, knew Carlos Quirino, and bought maps from the English dealer R.V. Tooley. The map was sold by León Gallery in their Kingly Treasures Auction in Manila on 2 December, 2023 for a record-breaking price for a Spice Map of Php.12,016,000 (US$218,000).

The first state, with the engraver’s name ‘Ioannes à Doetechum fecit’ in the lower cartouche, below three scale bars, can easily be identified because the title is printed separately in letterpress and glued into the title cartouche. The first state map sold in Manila has a watermark used by Claudon Vincent, a papermaker in the Papeterie de Grennevo in Docelles in the Vosges, between

1583 and 1609. On the second state, also published by Claesz before 1609, the title was engraved on the copper plate. According to Schilder, only five copies of the second state are known, all in institutional collections.

In 1617, after Claesz’s death, a third state of the map was published in Amsterdam by Claes Janszoon Visscher, who had acquired the copperplate. In the lower cartouche the engraver’s name is replaced by ‘CIVisscher excudebat Ao. 1617’. Although still rare, at least two dozen copies of the third state are held in institutional and private collections. In 1598 a pirated English copy of Plancius's map, engraved by Richard Beckit, was published in John Wolfe's Discours of Voyages into ye Easte & West Indies, an English translation of Jan Huygen van Linschoten's Itinerario.

The Petrus Plancius Spice Map has a special importance for Philippine collectors because it is the map from which Jodocus Hondius Jr. copied the Philippines for his miniature map Philippinae Insulae, published in 1598 in the small-format atlas Tabularum Geographicarum Contractarum by Petrus Bertius.

8

How PHIMCOS was Founded

by Mariano ‘Nito’ Cacho Jr. & Rudolf Johannes Hermann ‘Rolf’ Lietz

For the benefit of the many new members of PHIMCOS, we would like to tell you about the inception and early years of our Society.

Nito, a former Chairman of Far East Bank and an avid collector of coins, had expanded his extensive collection of rarities to include items of Filipiniana from the Philippine Struggle for Independence and the resulting SpanishAmerican and Philippine-American Wars, called the ‘insurrection’ by the Americans. In the process he inevitably encountered prints and especially maps that started to fascinate him, and after Rolf opened his Gallery of Prints in 1995 Nito asked his assistance in assembling one of the most extensive collections of Filipiniana maps and prints in the country

Through the years, our business relationship evolved into a true friendship based on professionalism in our dealings Nito appreciated Rolf’s advice to collect only material in prime condition, as reflected in the quality of Rolf’s own large collection of prints and the demands of the Gallery – even if Nito’s cries of ‘your price is too high!’ had to be buried in a good Riesling.

On one of those evenings in Nito’s residence, in February 2007, after a few glasses of an especially nice vintage, we discussed the merits of joining IMCoS, the International Map Collectors Society, which Rolf had represented in the Philippines since 1998. Nito said ‘what the heck, we do not even have one in the Philippines’, to which we looked at each other and said ‘so why don’t we form one?’ – and toasted with a loud Mabuhay!

The next day, we asked Nito’s legal counsel and the law firm retained by Rolf’s company Rudolf Lietz, Inc. to draft incorporation papers and bylaws for the ‘MCAP’ (Map Collectors Association of the Philippines). We compared and merged the two drafts, reducing the voluminous paragraphs. Rolf said that the name should be changed to PHIMCOS ‘as it is the Philippine IMCoS’, and Nito agreed.

We needed three more incorporators since, at that time, the rules of the SEC required five directors. We decided to invite some of our fellow collector friends to see who would accept and put down the initial Php.10,000 each; Nito solicited Alberto Montilla and Alfredo Roca, whom we both knew, and at Rolf’s request Dieter Reichert also accepted. A preliminary meeting was held on March 6, 2007 between the two of us and Alfredo; then on April 24, 2007 the first meeting of the five members of the PHIMCOS Board took place in Nito’s residence, aptly (for a map society) located in Homonhon St. near Magellan St. in Magallanes Village.

During our constitutional meeting of May 11, 2007, Nito was proposed and elected as President, with Rolf as Vice President, Alfredo as Treasurer, Albert as Secretary, and Dieter as Trustee, all in an interim capacity. Our secretariat was handled by Mariros Ripoll (the sister of our Board Assistant, Yvette Montilla). PHIMCOS was subsequently incorporated on June 25, 2007.

Other founding members for the first period of 2007 consisted of nine of our common friends, who then joined the five Board members for the first official PHIMCOS function at the Manila Polo Club on October 6, 2007: Ambassador Theo Arnold, Ian Fish, Dr. Leovino Garcia, Robert Lane, Dr. Jaime Laya, the late Dr. Benito Legarda, Alain Miailhe de Burgh, Ms. Consuelo N. Padilla and Edmundo Ramos.

At the first formal meeting, in the Manila Polo Club on January 28, 2008, the Board for 2008 was officially confirmed by the membership. At that meeting Rolf gave a presentation on ‘Robert Dudley's Life and Maps of the Philippines’, and Leo Garcia talked about ‘The Maps of Heinrich Scherer’. In May 2008, we arranged the first PHIMCOS exhibition, ‘European Impressions of the Philippines in the 16th and 17th Centuries’, held at the Metropolitan Museum of Manila with 50 maps lent by PHIMCOS members

And the rest is history …

9

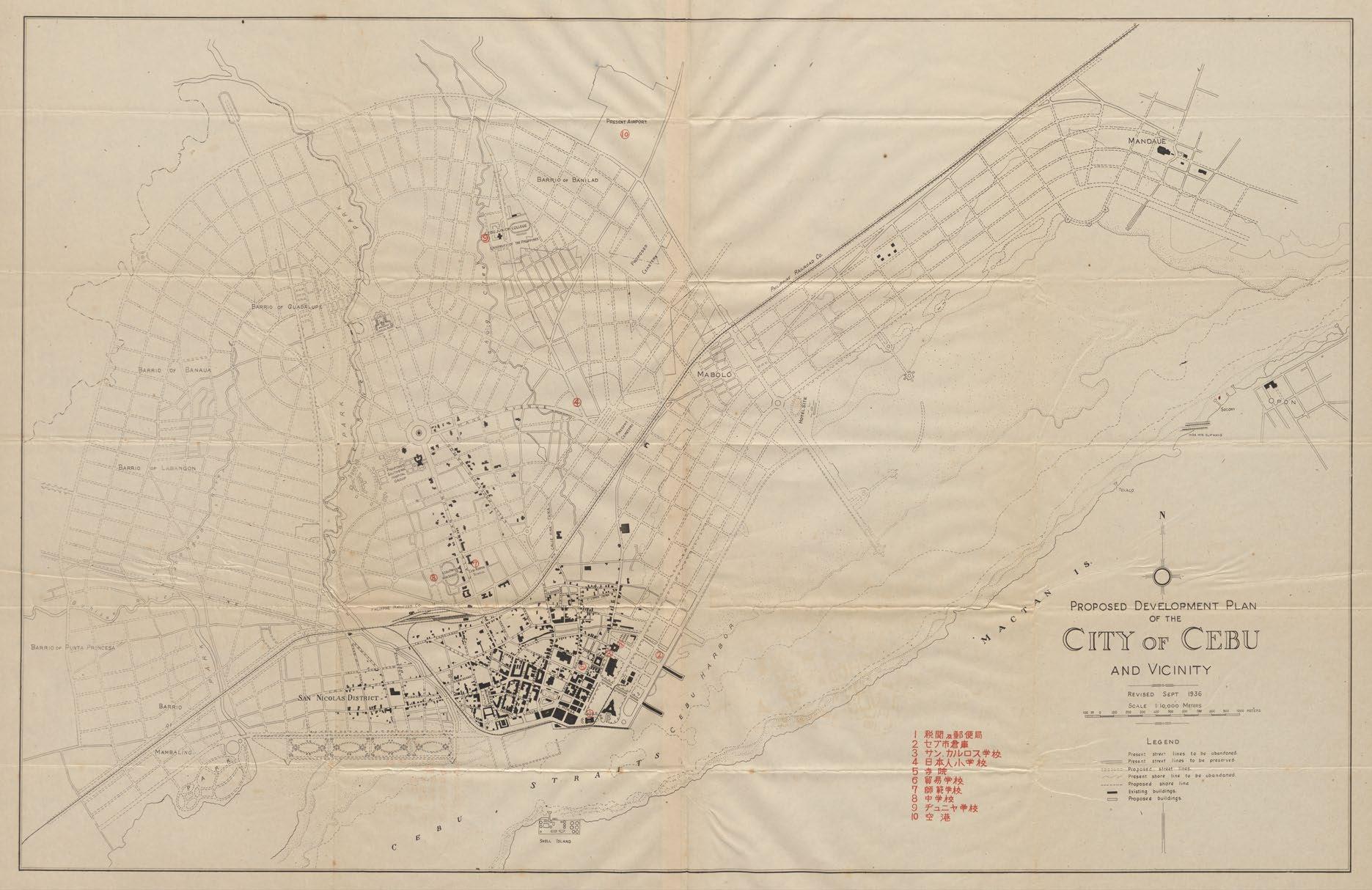

Proposed Development Plan of the City of Cebu and Vicinity

by Margarita V. Binamira

IN NOVEMBER 2023, when members of PHIMCOS were in Singapore for the opening of the Manila Galleon Exhibition at the Asian Civilizations Museum (see page 3), we were invited to see some of the maps in the Rare Materials Collection of the National Library of Singapore (NLS).

One map that caught our eye was the Proposed Development Plan of the City of Cebu and Vicinity. None of us had seen this particular map before, and the NLS’s example is particularly interesting because it has a key with Japanese notations, printed in red, that identify and highlight various locations in the city. The map, at a scale of 1:10,000 meters, carries a scale bar and a legend, but no information on where and when it was first published, who made it, or who printed it. The legend shows: Present street lines to be abandoned; Present street lines to be preserved; Proposed street lines; Present shore line to be abandoned; Proposed shore line; Existing buildings; and Proposed buildings.

In researching this map we found ourselves going back to the early 1900s, the American Colonial period in the Philippines. One major thrust of the American Colonial Government was to modernize and upgrade the cities and towns developed under the Leyes de Indias (Laws of the Indies). Under these Spanish laws, urban planning was centered around a plaza mayor (main square) surrounded by essential buildings such as the church, the casa real (royal house, the provincial seat of government) and the town hall, and by structures providing services such as schools, hospitals and clinics, and defense works.

American urban planning came to the Philippines largely through the efforts of the first civilian Governor-General of the Philippines, William Howard Taft. He instructed William Cameron Forbes, then a member of the Philippine Commission, to invite the architects and planners Daniel H. Burnham and Pierce Anderson to visit the colony and make general preliminary plans for Manila and Baguio. Proponents of the ‘City Beautiful’ concept, Burnham’s designs were

meant to showcase and ‘uplift’ these two cities with classical renaissance architecture and planned monuments. Tree-lined streets and avenues would direct the eye towards these monumental structures and de-emphasize the church-lined plazas from the Spanish period. At the same time, aside from the aesthetics, basic improvements to transportation, sanitary conditions and access to clean water were emphasized, and locations for hospitals and schools were identified.

After Burnham and Anderson left, a consulting architect for the colonial government was appointed to carry out the city plans. William E. Parsons was chosen for the position and stayed in the Philippines from 1905 to 1914. He was tasked inter alia with the interpretation of the Burnham and Anderson plans for Manila and Baguio, and the preparation of development plans for other cities based on Burnham’s work and urban design vision.

Parsons worked as the consulting architect for the Division of Architecture of the Bureau of Public Works (BPW), the precursor to today’s Department of Public Works and Highways. During his tenure he drew up city development plans, notably for Cebu and Zamboanga. After the general scheme was adopted, the next step was to build one or more of the buildings on the plan, which then necessitated the cutting of new streets. Once the main lines were fixed, the rest of the plan would take shape. At least that was the idea. In the case of Cebu, the Customs House was the first building to be erected, fixing its place permanently in the position it was given in the development plan. The Customs House still exists today, in the same location as in the Parsons plan, as the Cebu branch of the National Museum of the Philippines.

The 1912 development plan for Cebu City envisioned by Parsons included wide avenues, roundabouts, and the erection of the Cebu Provincial Capitol. It is this plan which we believe forms the basis of the Proposed Development Plan of the City of Cebu and Vicinity that we saw

11

Proposed Development Plan of the City of Cebu and Vicinity ‘Revised Sept 1936’, Japanese copy (image courtesy of Lim Shao Bin Collection, National Library, Singapore, ref. B29244774F)

in Singapore. Unfortunately, we have found images of the Parsons plan, but we have not been able to locate an original copy. After Parsons had left the Philippines, the Bureau of Public Works continued to undertake comprehensive city planning. From 1919 to 1935 this was increasingly done by Filipino architects, notably Tomás Mapúa and Antonio Toledo, working in the BPW’s Division of Architecture, with Juan Marcos Arellano as the Acting Consulting Architect.

We do not know when the Proposed Development Plan of the City of Cebu and Vicinity was first created; the only date given on the Japanese copy in the NLS is that it was ‘Revised Sept 1936’. We have been unable to find the first or any other earlier copy of this plan. According to email correspondence with Dr. Resil Mojares, in her book on the Capitol (op cit.) Architect Melva Rodriguez-Java writes: “When the Cebu Capitol project was revived in the 1920s, after having been shelved for a long time, the original Parsons plans could not be found and it was decided that Architect Antonio Toledo would be the one to draft a detailed set of drawings for the Capitol under Architect Arellano's supervision.” Also in email correspondence, Ian Morley has

explained that: “Toledo’s activities with the BPW were typically not of large-scale projects such as entire city plans. ... It was Arellano who tended to design large-scale planning schemes.”

The development plan of Cebu is strikingly similar to Arellano’s Proposed Development Plan of the City of Iloilo and Vicinity. That plan, at the same scale of 1 : 10,000, was first issued in 1926 and underwent at least six revisions before the final plan was drawn up, signed by Arellano as the Consulting Architect and approved by the Director of Public Works in 1930. The concepts for the two city development schemes are noticeably similar, as are the titles, typefaces, and legends of the two plans. Both plans involve parks, coastal / riverside developments, arterial boulevards with roundabouts, and new suburbs that incorporate the barrios that surround the cities. These similarities show that the BPW’s development plan for Cebu was essentially Arellano’s work, even if he did borrow some concepts from the 1912 Parsons plan.

New developments shown in Arellano’s plan of Cebu include the Proposed Southern Hospital Group; a second Proposed Cemetery; a Hotel Site; and the Proposed Capital (sic) Building. The

12

construction of Cebu’s provincial Capitol would begin in 1937, using the drawings drafted by Toledo under Arellano's supervision, and the building was inaugurated in 1938. In true City Beautiful fashion, the Capitol is neoclassical in spirit – grandiose, symmetric and imposing, yet with little ornamentation.

Interestingly, the NLS also holds a Japanese copy of the Proposed Development Plan of the City of Iloilo and Vicinity. This is a close copy of the original, albeit without Arellano’s name, but with a number of obvious typographic mistakes, and parts of the legend missing. Like the Cebu plan, it has a key with Japanese notations that identify and highlight various locations in the city

The Japanese maps in the NLS form part of the Lim Shao Bin Collection, donated in tranches to the library in 2016-17. Lim is a Singaporean businessman who studied and worked in Japan for many years. For personal reasons, in an effort to better understand World War II, he began collecting historic materials on Singapore and Southeast Asia. Whenever he found himself in Japan he would acquire items relating to the Japanese military history of the region. Part of the Lim Shao Bin Collection includes a cache of

more than 130 maps and atlases of Southeast Asia from the 1860s to the 2000s, many of them annotated in Japanese, including maps that Lim believes were some of the Japanese reconnaissance maps produced in anticipation of World War II.

In the case of this particular copy of the Proposed Development Plan of the City of Cebu and Vicinity, the Japanese notations list ten numbered locations within the city: (1) the Customs House and Post Office; (2) the Cebu City Warehouse; (3) San Carlos School; (4) the Japanese Elementary School; (5) a church (or temple); (6) the Trade School; (7) the Normal School; (8) the Middle School; (9) the Junior School; and (10) the airport. The Customs House has become the National Museum of the Philippines ‒ Cebu, and the Trade School is now the Cebu Technological University. The Normal School would be used by the Kempeitai (Japanese Military Police) during the war, and is now the Cebu Normal University. The Middle School has become the Abellana National School, and the Junior School is now the campus of UP Cebu. The airport at Lahug was transferred to Mactan Island in 1966 and the site has been redeveloped as the Cebu IT Park.

13

Detail from Proposed Development Plan of the City of Cebu and Vicinity (image courtesy of Lim Shao Bin Collection, National Library, Singapore)

Most of these Japanese annotated maps in the NLS come with a corresponding booklet of photographs, showing images of the indexed locations presumably for easy identification once on the ground. For this Cebu City map, the accompanying booklet of photographs in the NLS contains an aerial photograph of the city; another of the ‘principal commercial center’ (Magallanes Street); a view of the Plaza of Cebu, with the Customs House in the background; and photographs of the four buildings numbered (2) to (5). The caption for the photograph of No. (5) states that the church is the ‘Present-day Cathedral at Cebu’.

Other maps of the Philippines in the Lim Shao Bin Collection are annotated Japanese maps of Aparri, Baguio, Davao, Iloilo City (discussed above), Manila and Zamboanga. These are also believed to be Japanese reconnaissance maps. When the maps were copied and annotated in Japanese is not clear, but since all of them were copied from existing maps from the 1930s, and

the corresponding booklets of photographs are contemporary, it is clear that the Japanese undertook data collection and reconnaissance comprehensively before the outbreak of World War II. For the city development plans, Dr. Ricardo Trota Jose speculates that they may have been obtained from Filipinos working in the BPW; he also notes that before World War II Cebu had an active Japanese community. The map of Manila, at a scale of 1 : 11,000, is unattributed and undated, but appears to be a copy of the map of Manila published in 1935 by John Bach

This article would not have been possible without the invaluable assistance and information provided by Ms. Makeswary Periasamy and Ms. Gracie Lee, both Senior Librarians / Collections (Rare Materials) with the National Library of Singapore; Dr. Resil B. Mojares, Professor Emeritus at the University of San Carlos; Ian Morley, Associate Professor in the Department of History at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK); and Dr. Ricardo Trota Jose, Professor in the Department of History at the University of the Philippines, Diliman.

Proposed Development Plan of the City oi Iloilo and Vicinity (sic) ‘Revised Sept 1928 / Jone (sic) 1929 / Cot. (sic) 1930’, Japanese copy (image courtesy of Lim Shao Bin Collection, National Library, Singapore, ref. B29244772D)

14

Bibliograph y

Gracie Lee, ‘Prelude to War: Japanese Reconnaissance Maps’, in Stories From The Stacks, National Library Board, Singapore, Dec. 2020.

‒ ‒, ‘Japan in Southeast Asia: The Lim Shao Bin Collection’, in BiblioAsia Vol.14 No.2, National Library Board, Singapore, July-Sep. 2018.

Ian Morley, Cities and Nationhood: American Imperialism and Urban Development in the Philippines 18981916, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 2018.

‒ ‒, Tayabas: The First Filipino City Beautiful Plan, a paper presented at the 18th International Planning History Society Conference, Yokohama, July 2018.

‒ ‒, ‘The Filipinization of the City Beautiful 1916-1935’, in Journal of Planning History Vol. 17(4), Sage Publications, 2018.

‒ ‒, American Colonisation and the City Beautiful: Filipinos and Planning in the Philippines, 1916-35, Routledge, 2020.

Romeo B. Ocampo, ‘Planning and Development of Prewar Manila: Historical Glimpses of Philippine City Planning’, in Philippine Journal of Public Administration, Vol. XXXVI No. 4, October 1992.

A.N. Rebori, ‘The Work of William E. Parsons in the Philippines’, in The Architectural Record, Vol. XLI No. 4, April 1917 (Part I) and Vol. XLI No. 5, May 1917 (Part II).

Melva Rodriguez-Java, The History of The Capitol of Cebu: The History of Cebu Vol. 55, Provincial Government of Cebu, Cebu City, 2014.

Elgin Glenn R. Salomon, ‘Colonial Urban Planning and Social Control: The City Beautiful Plan of Iloilo City’, in Philippine Sociological Review Vol. 67, 2019.

15

Mapping Peoples and Places

by Mark Dizon

IN THE POPULAR imagination, most people usually associate maps with abstract, twodimensional depictions of space. Maps are flat, simplified geographical representations to help viewers pinpoint the location of specific places. But they are more than that. They also capture the beliefs and meanings of different times and places. Many historical maps are not simplified abstractions of geographical space.(1) They are littered with people, whether on the map itself or around its borders, indicating that actual people inhabited these landscapes. During the early modern period European mapmakers, confronted by a more interconnected globe, put different peoples and scenes of the world on their cartes-à-figures and other maps to convey to their audience the distinct cultures of faraway places. Spatial abstraction and mathematical precision were not necessarily the goals of these maps, which instead transported viewers to distant places through visual representations of their inhabitants.

The inextricable link between geography and people is visible in the personification of geographical areas such as continents and regions. Throughout the centuries, Europeans divided the world into different continents and represented these regions as people.(2) In the center of the title page of Gerardus Mercator’s Historia Mundi (1637), Atlas carries the weight of the earth on his shoulders.(3) At the corners of the page are the four continents personified: Europa, Asia, Africa and America. Each continent is depicted as a female figure with her own distinctive features, from her clothing (or lack of it) and accessories to the buildings, plants and animals in the scenery. The continents are not abstract spaces, but rather living and breathing people and places. We can see the same pattern of the personification of regions on the maps of Fr. Pedro Murillo Velarde, S.J. and Vicente de Memije, a Spanish creole living in Manila.

The text in the cartouche at the bottom of Murillo Velarde’s Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica delas Yslas Filipinas (1734), between the islands of Borney (Borneo) and

Mindanao, describes the archipelago and its different natural resources and inhabitants.(4) At the same time, the cartouche’s border is visually populated with several familiar figures you would have encountered in the Philippines. Near the top are a Chinese merchant with his parasol and fan, and a Negrito with his bow and arrow. At the right is an Igorot with his spear and shield, and at the bottom a man stroking his rooster while smoking a cigar. Maps are as much about the population as they are about geography. The eight vignettes that flank the map further confirm the importance of people in early modern cartography.

Title page of Historia Mundi or Mercator’s Atlas …, Second Edition published by Michael Sparke (1637) (image courtesy of David Rumsey Map Collection at Stanford University Libraries)

16

Details from the cartouche of Murillo Velarde’s Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica (1734) (images courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Memije’s Aspecto Symbólico del Mundo Hispánico (1761) is an even more obvious personification of geographical and political entities.(5) Besides continents and islands, the Hispanic monarchy is portrayed cartographically and allegorically as a crowned, standing female figure that has a global reach while gazing heavenwards to receive a flaming sword from two cherubs Her crown represents Spain, her mantle consists of Spain’s American colonies, her skirt is composed of the trans-Pacific routes of

the galleons, and her slippers are the Philippines.(6) In her left hand she holds the equinoctial line, depicted as the shaft of a staff from which flies the royal standard. In this map, geography itself is a person. Places, cartographical boundaries and routes define the symbolic figure that is the Hispanic monarchy.

Historically, places and people have been inextricably linked on maps, as we have seen in the cartographical personification of continents, archipelagoes and monarchies. Such a practice makes perfect sense, particularly in the holistic way the Hispanic monarchy gathered information about its distant realms. Royal officials used different methods, from reports and surveys to maps and actual specimens, to learn more about their territories.(7) Texts, drawings and objects became part of Spain’s vast knowledge of different places and peoples. This holistic approach meant that their geographical knowledge and cartographical endeavors were not merely concerned with charting empty, abstract spaces. Apart from describing the landscape and the natural resources of its various realms, knowing the inhabitants and subjects of the monarchy was a key element in assessing the value of a particular place. Even local maps of provinces in the Philippines, such as those by Fr. Bartolomé Marrón, O.P. and Fr. Alejandro Cacho, O.S.A., continued this practice of associating particular geographical spaces with certain people.

Seated at the provincial capital of Lal-lo in the north, the Dominicans were ecclesiastically in charge of Cagayan. In the 1690s, they had plans to expand their evangelization further southwards, into the interior of the province.(8) As part of these activities, the provincial of the Dominican order, Bartolomé Marrón, made a rough sketch of the territory based on eyewitness reports.(9) The map is oriented to the south, with the Pacific Ocean to the left (east), the northernmost coast of Luzon at the bottom, the Cordillera to the right (west), and the provinces to be conquered to the south at the top of the map. The dark, wavy lines indicate the mountains and the sea. The simple lines running through the plain are the Riogrande llamado Cagayan (Cagayan River) and its tributaries. Besides marking the Christian towns with a cross, the map also names the different indigenous communities inhabiting the Cordillera. From the

17

Aspecto Symbólico del Mundo Hispánico by Vicente de Memije (1761) (image © British Library Board, Maps K.Top.118.19)

perspective of the Dominican missionaries, the inclusion of people, especially unconquered groups, was an integral part of their mapping activities. After all, these maps visually tracked their religious successes in the form of mission towns and their pending evangelical projects in the animist communities they wanted to convert.

At the top of the map are the four provinces of Sifun, Yoga, Paniqui and Itui, which were targets of evangelization at that time. Far away from the provincial capital in Lal-lo, these provinces were at the vanguard of the missionary activities of the Dominican order. Marrón’s map depicts the four provinces as clearly bounded spaces, demarcated by rivers and mountains. It is a simplified, compartmentalized depiction of an unconquered, uncharted territory. In the cases of Itui and Yoga, the map names the province after its inhabitants, the Ituys and the Yogas respectively. Each ethnic group is tied to a particular area and landscape. This one-to-one correspondence between geography and

ethnicity is a fiction of the map, but it does show the continuing importance of people in the cartographical imagination, even in the local maps made by the missionaries. Mapping involved not only locating people, but also representing them visually ‒ even if only in the textual notation of their names.

The 1723 map of the mountains of Pantabangan and Carranglan by the Augustinian missionary Alejandro Cacho is another example of the prominence of people in missionary mapping.(10) In their evangelizing activities from the late-17th to the early-18th centuries, while Dominicans like Marrón moved from the north to the south in Cagayan, Augustinians including Cacho went the opposite way, starting from the south in Pampanga and moving their way to the north in Cagayan.(11) Like Marrón, Cacho highlighted the different nations or ethnic groups in the Augustinian missions. He divided the people into two groups: the converts in the mission towns and the independent communities in the surrounding mountains. At the center of the map, which is oriented to the northeast, the 22 circles with churches are the mission towns.

18

Mapa de la Vega del Río Grande llamado Cagayán by Fr. Bartolomé Marrón (1690) (image courtesy of Archivo General de Indias)

Along the top and left edge of the map are the unconquered ethnic groups represented by banderoles: Nacion de Ylongotes, Nacion de Yrapies, Nacion de Ytalones, and Nacion de Ygorrotes; the Nacion de Ysinais (in the process of becoming Christian) is also shown. Once again, people are embodied in the landscape. While the Christian converts occupy the white plains, the non-converts inhabit the surrounding black, green and red mountains and forests. Geography ‒ the division between lowlands and uplands ‒classifies the ‘civilizational’ character of the communities on the map.

So far, we have not seen the presence of actual human figures on the maps, which was a common practice in Renaissance cartography.(12) Mercator depicted the continents as female figures, Memije portrayed the Hispanic monarchy as a map in the form of a woman, Murillo Velarde surrounded his cartouche with the inhabitants of the Philippines, Marrón named provinces after ethnic groups, and Cacho represented the Christian / non-Christian divide in terms of a geographical split between plains and mountains. However, none of them placed depictions of actual people on the landscape

itself, which was a characteristic of the ethnographic style of European Renaissance maps. Our last example, Cacho’s ‘Mapa de una Parte del Norte de Luzon’ (c.1740), conforms to this mapping tradition that filled the landscape with drawings of its inhabitants.(13)

Cacho’s map portrays northern Luzon from Pampanga upward. Unlike Marrón’s and his own previous map, he did not merely write down the names of the different ethnic groups on the landscape. He also actually drew them to represent the various peoples living throughout northern Luzon, particularly the mission towns and their surrounding areas.(14) As on Cacho’s earlier map of Pantabangan and Carranglan, the ‘civilizational’ divide between Christians and animists is still a geographical divide between the lowlands and the uplands. On the map, rural, agricultural scenes represent colonial towns such as Arayat and Gapan, while hunting characterizes the surrounding mountains of the different groups of Negritos, known for their hunting skills. At the bottom of the map, near Arayat a man wields an axe while two women are pounding rice with pestles and mortar, and near Gapan two men hold their roosters in a cockfight.

19

Mapa de los pueblos existentes en los Montes de Pantabangán y Caranglán by Fr. Alejandro Cacho (1723) (image courtesy of Archivo General de Indias)

(image courtesy of Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin) (15)

The bottom right edge of the map portrays a section of the mountain abode of non-Christian communities; a Negrito with a bow and arrow is shooting at a deer, while another is aiming at an unsuspecting passerby.

Besides depicting actual and potential converts on his map, Cacho also illustrates the extent of the Spanish presence in Cagayan. Near Lupao a rider on horseback spears a deer. At the top of the map, we see Lal-lo, the only site that approximates a populous city with its several houses. A disproportionately large man with a sword and elaborate attire, most likely a representation of the Spanish provincial governor, towers over the town. A galleon ship is either anchored at the shore or passing nearby. In mid-18th century Philippines, Cacho carried on the Renaissance tradition of putting human figures and everyday scenes on maps. He combined cartography and ethnography, reminding viewers that these places were populated by actual people, and that these people made these places.

Maps are as much about people as they are about places. Continents and regions were

personified in stereotypical characters and inhabitants. In the early modern period, as Europeans learned more about the other continents, visual representations of distant lands in the form of representative human figures were a way to satiate the European appetite for knowledge about the world. In a way, Renaissance-style maps that combined ethnography and cartography lived on in the works of Murillo Velarde, Marrón and Cacho centuries later. The inhabitants of the Philippines ‒ whether as human figures in stereotypical conventional poses and costumes or as ethnic names on the landscape ‒ were visually present on the maps of these missionaries.

20

Mapa de una Parte del Norte de Luzon by Fr. Alejandro Cacho (c.1740)

Details from Mapa de una Parte del Norte de Luzon by Fr. Alejandro Cacho (c.1740)

Although 18th-century mapmaking saw a trend toward the abstraction of space through precise measurements and clear boundaries, missionary mapmakers adhered to a more traditional cartography. They combined both topography and ethnography. They highlighted the people on their maps, documenting their success by the people they had converted and the work still to be done in the people to be converted. A missionary’s primary goal was to save souls, and it showed in the presence of people on their maps. As mapmakers, missionaries were not only geographers, but also ethnographers, and their maps of the Philippines almost always had a human element.(16)

The missionaries may have portrayed some unconverted people, such as the Negritos, in a negative light, but they nevertheless acknowledged the presence of the native inhabitants cartographically. Whether as blocks of generic spaces, names on the landscape, or stick figures

References

performing ‘barbaric’ acts, the independent indigenous people of the archipelago revindicated their existence outside of colonial control, however indirectly, on the maps.

In the Renaissance and early modern world, our contemporary division of disciplines did not exist. Cosmography, geography, ethnography and cartography flowed into one another as an overall inquisitiveness to know and understand the world. Mapmakers, missionaries and monarchs all exhibited the same desire to map places and their people.

Mark Dizon is an assistant professor in the Department of History at Ateneo de Manila University; his research focuses on cross-cultural encounters in the early-modern Philippines. This article expands the presentation on ‘The Human Element in Fr. Alejandro Cacho’s Missionary Maps’ which he gave to PHIMCOS on July 19, 2023

1. Surekha Davies, ‘Maps’, in Information: A Historical Companion, edited by Ann Blair et al., Princeton University Press, Princeton, Oxford and Beijing, 2021.

2. Martin W. Lewis and Kären Wigen, The Myth of Continents: A Critique of Metageography, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1997.

3. Gerhard Mercator, Jodocus Hondius and Wye Saltonstall, Historia Mundi or Mercator’s Atlas , Second Edition, T. Cotes for Michael Sparke and Samuel Cartwright, London, 1637; Valerie Traub, ‘Mapping the Global Body’, in Early Modern Visual Culture: Representation, Race, and Empire in Renaissance England, edited by Peter Erickson and Clark Hulse, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 2000.

4. Pedro Murillo Velarde, Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica delas Yslas Filipinas dedicada al Rey Nuestro Señor por el Mariscal de Campo D. Fernando Valdes Tamon Cavallo del Orden de Santiago de Govor. y Capn. General de dichas Yslas, / Le esculpio Nicolas dela Cruz Bagay Indio Tagalo, Manila, 1734.

21

Detail from Mapa de una Parte del Norte de Luzon by Fr. Alejandro Cacho (c.1740)

5. Vicente de Memije, Aspecto Symbólico del Mundo Hispánico puntualmente arreglado al geografico, Manila, 1761.

6. Ricardo Padrón, ‘From Abstraction to Allegory: The Imperial Cartography of Vicente de Memije’, in Early American Cartographies, edited by Martin Brückner, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2011; Carlos Quirino, Philippine Cartography 1320-1899, Fourth Edition, edited by Dr. Carlos Madrid, Vibal Foundation, Quezon City, 2018.

7. Daniela Bleichmar, ‘The Imperial Visual Archive: Images, Evidence, and Knowledge in the Early Modern Hispanic World’, in Colonial Latin American Review Vol. 24, No. 2, 2015; Barbara E. Mundy, The Mapping of New Spain: Indigenous Cartography and the Maps of the Relaciones Geograficas, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1996; María M. Portuondo, Secret Science: Spanish Cosmography and the New World, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 2009.

8. ‘Petición del dominico Alonso Sandín sobre nuevas conversiones en Filipinas’, August 27, 1696, ref. no. FILIPINAS, 83, N.52, Archivo General de Indias, Sevilla.

9. Bartolomé Marrón, ‘Mapa de la Vega del Río Grande llamado Cagayán, hasta las provincias de Sifún, Yoga, Paniqui, Itui, etc., en el que se señalan misiones y pueblos’, September 8, 1690, ref. no. MP-FILIPINAS, 140, Archivo General de Indias, Sevilla.

10. Alejandro Cacho, ‘Mapa de los pueblos existentes en los Montes de Pantabangán y Caranglán, entre las provincias de Pampanga, Pangasinan y Cagayán, pertenecientes a las misiones de los religiosos de San Agustín’, February 18, 1723, ref. no. MP-FILIPINAS, 148, Archivo General de Indias, Sevilla.

11. Mark Dizon, Reciprocal Mobilities: Indigeneity and Imperialism in an Eighteenth-Century Philippine Borderland, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2023; Carlos Villoria Prieto, Un berciano en Filipinas: Alejandro Cacho de Villegas, Publicaciones Universidad de León, León, 1997; Carlos Villoria Prieto, ‘Los Agustinos y la misión de Buhay a principios del siglo XVIII’, in Archivo Agustiniano Vol. LXXXI, No. 199, Valladolid, 1997

12. Surekha Davies, Renaissance Ethnography and the Invention of the Human: New Worlds, Maps and Monsters, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2016.

13. Angel Pérez (editor), Relaciones Agustinianas de las razas del norte de Luzon, Department of the Interior, Ethnological Survey Publications, Vol. III, Spanish Edition, Bureau of Public Printing, Manila, 1904.

14. Mark Dizon, ‘Cartographic Ethnography: Missionary Maps of an Eighteenth-Century Spanish Imperial Frontier’, in Imago Mundi Vol. 71, No. 1, 2021.

15. The map is reproduced as Plate III in Relaciones Agustinianas de las razas del norte de Luzon (op cit).

16. Joan-Pau Rubiés, ‘Ethnography and Cultural Translation in the Early Modern Missions’, in Studies in Church History Vol. 53, Cambridge University Press, 2017; and ‘The Spanish contribution to the ethnology of Asia in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries’, in Renaissance Studies Vol. 17, No. 3, Wiley, 2003

22

The Map That Never Was Alexander Dalrymple's Unpublished ‘Chart of the Philipinas’ by

Peter Geldart

AL EXANDER DALRYMPLE (1737–1808) was the most important British cartographer of Asia in the 18th century I n 1779 he was retained (for the rest of his life) by the Honourable East India Company (EIC) for their hydrographic work, and in 1795 he was appointed as the first official Hydrographer to the British Admiralty A prolific cartographer, Dalrymple compiled, edited, wrote and/or published over 1,350 marine charts, plans, sheets of views, sailing directions, memoirs and books, including some 95 charts, plans and sheets of views of the Philippines. Of these, his three- sheet Chart of the Philipinas is one of the least- well known –because it was never completed.

Born in 1737 at Newhailes near Edinburgh, Dalrymple was the seventh son and one of 15 children of Sir James Dalrymple, 2nd Baronet. He was educated at a school in the nearby town of Haddington. At the age of 15, he was officially appointed as a Writer (c lerk) in the EIC and sailed for India, arriving at Fort St. George in Madras in May 1753 on board the Suffolk (Captain William Wilson). Because his handwriting was not up to the standards of legibility required by the EIC, Dalrymple was initially given a post as Assistant Storekeeper. However, through a family connection he had the support and encouragement of George Pigot, the new Governor of Madras Presidency, and in 1755 he was moved to the Secretary’s office, appointed to learn assaying, and taught to write ‘a very good and fluent hand’. (1) In May 1757 he was promoted to Deputy Secretary.

Two years later Dalrymple stepped aside from the promotion ladder to make the first of his three voyages to the eastern seas, including the Philippines. His purpose was to explore opportunities for British trade in the East Indies and the new route from Madras to China pioneered in 1757- 59 by Commodore Wilson in the Pitt. This so - called Eastern Passage, also known as Pitt’s Passage, went south of the Equator (via Batavia, the Spice Islands, and the northwest coast of New Guinea), then northeast to the east

of the Philippines, and finally around Luzon and northwest to Macao. The passage was to be used increasingly by East Indiamen keen to avoid the dangers of the China Sea, especially at times of war.

Dalrymple left Madras in April 1759, travelled to Malacca on the Winchelsea, and embarked on the schooner Cuddalore (Captain George Baker), where he took command of the ship. They reached Macao in early July, and the Cuddalore then spent two months exploring the islands to the north of Luzon. The ship returned in October 1759, and Dalrymple spent six months in Macao sorting out a dispute with the Portuguese and Chinese authorities over nine men who had deserted from the crew. He took the opportunity to make and collect charts and views of the Pearl River Delta and adjacent islands and coasts.

A portrait of Alexander Dalrymple at Newhailes, wearing the uniform of a sea-officer of the East India Company, in a painting of c.1765 attributed to John Thomas Seton (copyright © National Museums Scotland )

23

Dalrymple’s untitled and undated chart of parts of Luzon, Mindoro, Panay, Guimaras, and Negros (image courtesy of U.K. Hydrographic Office, ref. no. v53 Bb3 )

After a brief visit to Tourane in Cochin China, the Cuddalore returned to Canton and then set sail again on 30 December, 1760 as escort to five East Indiamen returning to England by way of Mindanao . There, Dalrymple stayed on to carry out coastal surveys locally, to the south and in the Moluccas; the Cuddalore then returned to Madras in January 1762 via Zamboanga, Manila, and the west coast of Palawan.

That summer, Dalrymple undertook his second voyage to the Philippines, in command of the packet ship London He revisited Borneo and the Sulu Archipelago in order to deliver cargo to his trading partners There he learned of the capture of Manila by the EIC and other British forces in October 1762. He took formal possession of the settlement on the island of Balambangan, which he intended was to be used as a British trading post, in January 1763, and was back in Madras in March. As he wanted to explain his Balambangan enterprise to the EIC’s Court of Directors in London in person, Dalrymple resigned from the Company and received permission to return to England.

On his third (and last) voyage to the Philippines, he left Madras in July as a passenger on the East Indiaman Neptune and set sail for Canton with orders to call at Sulu en route. At Malacca they were joined by the London. After a short but problematic stay at Sulu, and caught up in a web of intrigue between the Sultanate and the Spanish, Dalrymple decided to continue by way of Manila, where he arrived in October, 1763.

In Manila, Dalrymple reported to the DeputyGovernor, Dawsonne Drake, who called Dalrymple ‘my secret Enemy’. (2) Following bitter disputes with his Council, including allegations of extortion and embezzlement, Drake was forced to resign; on 29 March, 1764 the Council appointed Dalrymple as Provisional DeputyGovernor of Manila. Two days later he officiated at the f ormal ceremony and banquet at which Britain handed the occupied territories back to Spain. In April, the British fleet set sail for home, accompanied as far as Mindanao by Dalrymple, again in command of the London. After spending more time in Sulu and two months surveying the coasts of China , he went home in July 1765.

24

After his return to England, Dalrymple continued to promote his proposed trading settlement on the island of Balambangan; expounded the theory of the Great Southern Continent; and encouraged the exploration of the Pacific Ocean. However, he declined to join the Royal Society’s voyage to the southern seas to observe the transit of Venus in 1768 in HMS Endeavour because it was being led by Captain James Cook, a Royal Navy captain – which Dalrymple was not, making him ineligible to be in command of the expedition as he wanted.

By 1769 Dalrymple had established his position in London. For the next six years his main activity was the publication of charts, plans and memoirs, either based on his own surveys and observations or acquired from indigenous and other sources during his three voyages. By the end of 1771 he had published six memoirs and six charts of the China Sea, the coasts of China, the coast of Borneo, Balambangan, the Sulu Sea, and the west coast of Palawan. He also wrote pamphlets on EIC politics and on the Balambangan project. He was proposed for the Royal Society by Benjamin Franklin, and admitted in March 1771. A Collection of Charts and Memoirs was published in 1772, and that year he published a chart of the Bay of Bengal that had been given to him by the EIC . He then resumed his plans to publish his own charts, especially those of the Philippines ‘ from Balambangan to China ’ , including a Chart of the Philipinas

In 1773 Dalrymple was diverted from his other projects, initially by his dispute with Dr. John Hawkesworth over the latter’s official account of Cook’s voyage, and then by the launch of a new project to publish (by subscription) A Collection of Plans of Ports in the East- Indies. Issued in six parts, from February 1774 to March 1775, the collection comprised 83 plates (including 14 of the Philippines). The following month Dalrymple departed for India, where he stayed until returning to England in 1777; he left most of his books and maps in Madras, and these were not shipped back to him until 1781.

Although the engraving of charts for Dalrymple’s other projects had continued in parallel with publication of A Collection of Plans of Ports, ‘ the forced hiatus from 1776 to 1781 had broken the continuity of his work’ ( 3) He had become frustrated in his search for reliable cartographic

Dalrymple’s untitled and unfinished chart of parts of Luzon and adjacent islands dated Sepr. 24 th 1781 (image courtesy of Library of Congres s , Geography and Map Division , G1059.D23 Ma ps 3b58 )

A detail of the above chart

information on the Philippine archipelago; the Balambangan settlement had been abandoned;(4) and with the adoption of chronometers the EIC’s ships needed charts with details of longitude not shown on the older charts. Dalrymple concentrated on his new job as the EIC’s de facto hydrographer, ( 5) responsible ‘ for examining the Ships Journals from the earliest times … and for publishing from time to time such Charts and Nautical Directions as a comparison of the various Journals and other Materials may enable him to do ’ ( 6) Dalrymple's final reference in print to his collection of charts and memoirs of the Philippines as ‘ a Separate Work not yet published’ ( 7) was in 1783

25

Track of the Schooner Cuddalore, along the East Coast of Panäy; by ADalrymple, 1761 , dated January 6 th, 1775 (image courtesy of U.K. Hydrographic Office, ref. no. v51 Bb3 )

Dalrymple certainly planned to publish his Chart of the Philipinas, described in 1774 as ‘ another Work I have now in hand, viz. a Chart of the Philipinas which will be accompanied with Nautical Observations and Instructions and many Views of Land’ ( 8) The chart was to comprise three sheets.

The southernmost sheet was a revised state of Dalrymple’s well- known chart A Map of part of Borneo, and The Sooloo Archipelago. The chart was first published o n 20 October, 1769, and the first state of the map was copied as Plate 54 in the second edition of Le Neptune oriental. For his Chart of the Philipinas, he added soundings along the coasts of Borneo and throughout the Sulu Archipelago, and a dded ‘Republished with the Additions Feby. 2d 1775’ to the imprint ( 9)

The other two sheets of the proposed Chart of the Philipinas were on the same scale as the bottom sheet of approximately 20 nautical miles to the inch. These were engraved, but have survived only as proof states now retained in institutional collections:

• an untitled, undated chart that shows parts of Luzon, Mindoro, the Cuyo Islands, Panay, Guimaras, ‘ Buglas or Negros’, Camiguing and northern parts of Mindanao (Dapitan and Surigao); because it was designed to be joined to its neighbours, the chart has no borders outside the neatlines at top and bottom;(10) and

• a sketchy, untitled and clearly unfinished chart dated Sepr. 24th 1781 that shows the Batanes and Babuyanes islands (unnamed), parts of the west coast of Luzon from Cape Bajador (sic ), Bigan (sic ) and Cape Bolinao to Manila , and part of the east coast with Lampon Bay and the islands of Polillo and Alabat. ( 11)

As part of his project to publish charts of the Philippines Dalrymple also produced proof states of three charts, drawn on a larger scale of approximately 10 nautical miles to the inch, which were engraved by William Whitchurch of Islington (with Dalrymple’s imprint at the bottom) but not published for sale:

• Track of the Schooner Cuddalore, along the East Coast of Panäy; by ADalrymple, 1761, dated 6th January, 1775, which shows a line of soundings from the strait between Ylo Ylo (sic) and Guimaras, through the islands along the east coast of Panay, and then northwards, to the west of Great Tabones to wards the island of Sibuyan;( 12)

• Chart of Part of the Philipinas, Laid down chiefly from observations in 1761, & 1764 by ADalrymple, dated April 5th, 1775, which shows part of the southern coast of Luzon, Luban, most of Mindoro, part of Marinduque, Tablas, Romblon, Sibuyan, Ylin, and other adjacent islands;( 13) and

• Chart of the Cuyos, and Part of Panay, dated April 14th, 1775, which shows the Cuyos Islands with soundings and parts of the west coast of Panay from Dahay to Pt. Nasog . (14)

26

Chart of Part of the Philipinas , … by ADalrymple, dated April 5 th, 1775 (image courtesy of U.K. Hydrographic Office, ref. no. v5 0 Bb3 )

Dalrymple’s Chart of the Cuyos, and Part of Panay, dated April 14 th , 1775 (image courtesy of U.K. Hydrographic Office, ref. no. v52 Bb3 )

27

Portrait of J-B.N.D. d’Après de Mannevillette (15) (image courtesy of Antiquariat Daša Pahor)

Dalrymple delayed and eventually abandoned the publication of his Chart of the Philipinas because of the problems he encountered. He had difficulty in reconciling his own surveys of coasts, headlands and islands, together with his ships’ tracks, with the features shown on earlier charts he had viewed or collected (whether Dutch, French, Spanish or British). He also found it difficult to obtain reliable charts or surveys of those parts of the archipelago that he himself had not visited. He set out his requirements, and the limits of his own surveys, in a series of letters he sent from 1768 to 1771 to the great French cartographer J- B.N.D. d'Après de Ma nnevillette:

I have Some thoughts of publishing a Set of Charts of Borneo & the Philipinas from my own observations & the Collections I have made; I have already made considerable progress in the delineation of the Northern part of Borneo & the Philipinas.(1 6 )

I shall think it a great favour if you will oblige me with a list of the Charts & particular plans you have of the Philipinas.(1 7 )

In my Letter of 31st Jany I begd (sic) a List of the Charts & Plans you mean to engrave; & a List of Charts and Particular Plans of the Philipinas in your possession.(1 8 )

I have myself passed along the No. Coast of Magindanao or Mindanao, along the Wn. Coast of Paragua, ... along the W. Coast of Mindoro, Pany (sic) & Negros three times, thro the Cuyos once; & once between Pany & Negros & thence to the Eastward of Sibuyan into the common track of the Galleons to the South of Marinduque & along the Coast of Luzon.(1 9 )

I am now engaged in compleating (sic) the Charts of my own voyages thro' the Philipinas & other parts of the Eastern Islands.(20 )

D'Après de Mannevillette, the hydrographer to the Compagnie française pour le commerce des Indes orientales (the French East India Company), had published the first edition of his atlas of charts of the eastern seas, Le Neptune oriental, in 1745. Dalrymple first wrote to him in February 1767, and by the time of d'Après de Mannevillette’s death in 1780 Dalrymple had sent him 80 letters and received some 50 in reply. (21) The exchange of letters, charts and nautical information between the two cartographers was mutually beneficial. D'Après de Mannevillette copied six of Dalrymple’s charts for the second edition of Le Neptune oriental (published in 1775), and Dalrymple published copies of the charts he received from Monsr. D’Aprés, notably the Spanish chart of Palawan titled Chart of Faveau’s Voyage (1781).

Dalrymple kept d'Après de Mannevillette informed of his Philippines project although, a ccording to Dr. Andrew S. Cook, he continued their correspondence in 1772 and 1773 without mention of his plans for the Chart of the Philipinas (22) But Dalrymple returned to the subject in 1774:

I am at present engaged in compleating (sic) the Charts mentioned in the enclosed paper: my own Views of the Lands amongst the Philipinas are very numerous and very general, but having never passed the Embocadero, I have no Views and very few Observations concerning that part: If M. Crozet's Voyage contains any I flatter myself You will oblige me with them. […] I intend to engrave on the Plate [of the Philipinas] what is laid down from my own Observations; and, after taking a few Impressions from it in that State, to add from what other materials I have, or can collect, such parts as I have not been able to lay down from my own observations.(2 3 )

28

I am very impatient to see M. Crozet's Voyage (2 4 ) as I have at present in the hands of the Engraver a Chart of the Philipinas; this Chart contains my own Tracks thro' these Islands but I mean to add the other parts from the best materials in my possession and hope to obtain assistance from M. Crozet: The Chart I have in hand will join to that already published of the No. part of Borneo & the Sooloo Islands to which I have added the Soundings, and in two other Plates will extend to Formosa comprehending the Bashees &c.(2 5 )

But by 1783 Dalrymple had abandoned his partly- engraved but still unpublished Chart of the Philipinas. Why was it never completed? We know this was mainly because he had failed to find the additional charts or detailed descriptions he needed to complement and validate his own observations, and to fill in the areas of the Philippines he had not visited in person. But until recently we did not know the exact information that he was lacking. This has now been revealed, in a previously- unrecorded, unpublished, bifolium manuscript letter from Dalrymple dated 20th August, 1773. (26)

In the first paragraph of the letter he thanks his correspondent for the latter’s letter dated 12th Sept. [1772] received ‘at a time when I was in the country’, and states that he is enclosing a ‘map of Bengal … published a few days ago’ that is ‘ pirated and not published by authority of the Company’. (27) In the following paragraph he continues:

I have in view to publish a Map of the Philipinas in which perhaps You can afford me assistance. I shall therefore mention what I have in my possession besides those inserted in N 17 & 16 of the List I have published from whence You will see whether there are any things in your Collection which can be of use to me. I flatter myself your known inclination to promote Geographical Knowledge will secure to me your kind assistance and my Friend Mr. Orme who has taken charge of this Letter will pay to you whatev er expence (sic) may attend the making copies of what you may be so obliging as to favour me with.

The letter proceeds to list the places for which Dalrymple already has some charts, followed by the provinces and coasts for which he is seeking information:

The M.S.S. in my collection are

The Environs of Manila geometrically determined but containing only the positions of places and not the detail of the country.

Province of Bulacan on Luzon, but I have no materials to place it in the true situation with respect to Manila.

Southern part of Limbones on Luzon, the part adjacent to Manila Bay & Cavite is wanting.

Valer on East Side of Luzon – wants a scale and Latitude & Longitude of some place, or any other materials to affix it in its true situation.

Province of Cagayan on Luzon – NB. this is of doubtful authority –

Mindanao adjacent to Dapitan.

Besides materials for adjusting the situations of these maps I am particularly in want of materials concerning the Provinces of Pangasinan, Pampanga, Tayabas , Taal, & Camarines on Luzon, The plan I have of Camarines being very bad. I have not any thing circumstantial of Zebu, nor concerning the No side of Pany and but little of Mindoro, Samal &ca except my own tracks between Pany & Negros , along the West Coasts of Mindoro & Pany & along the No. Coast of Mindanao but my own observations on the last are scarce more than sufficient to determine the direction & extent; I have nothing I can rely on for the East or So parts of Mindanao.

The letter ends: ‘I have the honour to be / Sir / Your most obedient Humble Servant / ADalrymple / Soho Square / 20th. August 1773’.

[ Note : the words underlined above are copied as such from the letter. ]

Unfortunately, the letter has no envelope and the addressee’s name is missing, probably because it was enclosed in a larger package containing the map; consequently its recipient is unknown. Dr. Cook is firmly of the opinion that it was not sent to d'Après de Mannevillette, because it does not fit into the known sequence of letters exchanged between the two cartographers that year. (28) Also, he notes that Dalrymple would not have signed a letter to d'Après de Mannevillette as ‘Your most obedient Humble Servant’ (which has been altered from ‘obliged’).

29

Letter from Alexander Dalrymple to an unknown correspondent dated 20 th August 1773 (author’s collection ; images courtesy of Daniel Crouch Rare Books )

A likely explanation for the more formal valediction is that Dalrymple was writing to a social or (formerly) direct superior, perhaps a senior EIC official, or an army or naval officer, with whom he had been in contact but did not know very well. This would explain why he was

sending the letter through ‘ my Friend’ Robert Orme, (29) who had extensive co ntacts with the EIC hierarchy. Orme did not return to India after 1760, so the likelihood is that he was asked to deliver Dalrymple’s letter to someone who had also returned from India and was then living in

30

Britain. It is tempting to speculate that this could have been Lieutenant- General Sir William Draper K.B. who, after commanding the British occupation of Manila, had returned to England with £5,000 prize money from the EIC . I n 1773 Draper was living in semi- retirement in his house, ‘ Manilla Hall’ , at Clifton near Bristol. ( 30)

Apparently the letter was either not delivered or left unanswered. Although we cannot identify its recipient without further research, the letter

Bibliography

does shed light on Dalrymple’s frustrating and frustrated search for the information he needed to complete his Chart of the Philipinas. But the preliminary proof states of his charts and, especially, this newly- discovered letter do give us a clearer picture of how ‘ The Map That Never Was’ would have looked had Dalrymple been able to complete it

This article is based on the presentation given to PHIMCOS by the author on 13 November, 2019

Alexander Dalrymple, ‘Memoirs of Alexander Dalrymple, Esq.’, in The European Magazine, and London Review, Vol. 42, Philological Society of London, November 1802.

Andrew S. Cook, Alexander Dalrymple (1737 -1808), Hydrographer to the East India Company and to the Admiralty as Publisher: A Catalogue of Books and Charts, doctoral thesis , University of St. Andrews , 1992.

‒ ‒, ‘An exchange of letters between two hydrographers : Alexander Dalrymple and Jean-Baptiste d’Après de Mannevillette’, in Les Flottes des Compagnies des Indes 1600 -1857 , Service Historique de la Marine, Vincennes , 1996.

Andrew C.F. David, A Catalogue of Charts and Coastal Views published by Alexander Dalrymple 1767 -1808 privately, as Hydrographer to the East India Company (1779 -1808), and as Hydrographer to the Admiralty (1795 -1808) and their subsequent history (1767 -1959), private publication, 1990.

Howard T. Fry, Alexander Dalrymple and the Expansion of British Trade, The Royal Commonwealth Society Imperial Studies No. XXIX, Frank Cass & Company Limited, London, 1970

References & Notes

1. ‘Memoirs of Alexander Dalrymple, Esq.’ op cit .

2 From Drake’s correspondence with the EIC’s Court of Directors , quoted by Nicholas Tracy in Manila Ransomed: The British Assault on Manila in the Seven Years War, University of Exeter Press, Exeter, 1995

3 Cook 1992 op cit , p. 85.

4. The trading settlement on Balambangan was approved by the Company in 1768 and established in 1773 under John Herbert , but was a failure Described as ‘a riot of fraud and peculation’ (Vincent T. Harlow in The Founding of the Second British Empire 1763 -1793 , Vol. 1, Longmans, London, 1952 ), on 26 February, 1775 it was destroyed by Moro pirates led by Dato Teting, a first cousin of Sultan Israel of Sulu