DEEP LOOKING Take a deeper look into the Museum’s Western American art collection with Tim Rodgers, PhD, the Museum’s Sybil Harrington Director and CEO, as he provides insight into the work of Willard Nash.

I

G O WILL W ARD E SNASH T YOUNGMAN

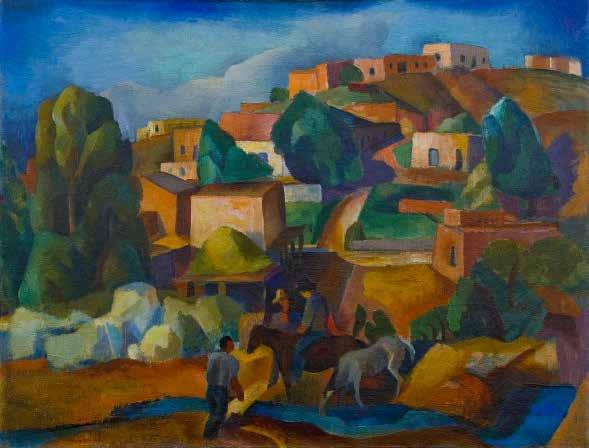

n search of good health and the “real” America, young artists such as Willard Nash (1898-1942) settled in New Mexico to paint the dramatic landscapes and Indigenous peoples of the region. He arrived in 1920 in response to an invitation from Mabel Dodge Luhan—the eccentric, East Coast heiress—to visit her compound in Taos. Luhan issued many such invitations with the hope that New Mexico’s scenic beauty and Indigenous cultures might inspire artists to create new work and establish art colonies in the West. Many now-famous artists, writers, and dancers, including Ansel Adams, Martha Graham, D.H. Lawrence, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Paul Strand, enjoyed Luhan’s generosity and created some of their finest works in response to the land and cultures they considered unfamiliar. In New Mexico, Nash quickly became part of a painting group called Los Cinco Pintores (The Five Painters) that included Jozef Bakos, Fremont Ellis, Walter Mruk, and Will Shuster. Although the artists exhibited together, their work shared very few stylistic similarities. Nash, more so than the other painters, relied on his familiarity with European artists and their work to inspire his creations. Seen here, in this 1925 painting, Untitled (Santa Fe Landscape), which is now in the collection of Phoenix Art Museum, Nash’s admiration of the art of Cézanne is apparent in the building block-like construction, the rough patches of colors, and the interest in a rural landscape dominated by a mountain. Both Cézanne and Nash were looking for terrain and an artistic style that declared a specific personal aesthetic and a national identity—whether French or American—and found them in rural, rugged landscapes painted in a rough-hewn manner. Nash, however, like so many artists who traveled and settled in the West during the teens and ’20s, was motivated to relocate because of more personal needs. His original visit to New Mexico in 1920 was prompted by a bout of Spanish flu, and like numerous fellow travelers, Nash hoped that the fresh, dry, unpolluted air of New Mexico would benefit his recovery. Later in life, after moving to California to be an art professor, he returned to New Mexico in 1942 to recover from tuberculosis. He settled in Albuquerque with the same belief that the high desert air would relieve his suffering. Unfortunately, Nash never recovered and passed away at the young age of 44. Illness, creativity, national identity, and a need to escape urban life and its mores—these are the ingredients of the lives of many early Western artists. Some found the utopia they sought; others struggled with poor health and poverty. Although Nash relocated to New Mexico more than 100 years ago, his motivations for doing so still resonate. How many of us moved West in search of good health, renewed creativity, and authenticity? In this time of another pandemic, we can empathize even more deeply with Western artists who gave up their settled lives to search for well-being and clear minds guided by a reset moral compass. image credit: Willard Nash, Untitled (Santa Fe Landscape), c. 1925. Oil on canvas. Museum purchase with funds provided by Betty Van Denburgh and Western Art Associates in honor of its 40th Anniversary.

WINTER/SPRING 2021 / PHXART.ORG

9