5 minute read

RICK MILLER’S HOMECOMING

BY KERRY MANDERS

Geneviève Thibault, “Childhood Revisited 3,” Sunny Bank, Gaspé, QC, 2018.

“This room provided insufficient refuge from my suicidal ideation. What had been an idyllic childhood location lost its sense of safety as my teenage depression spiralled downwards.”

“I’M A CRAZY PERSON,” Rick Miller laughs, adding, “I’m allowed to say that, but you probably shouldn’t.” It was as a Mad Artist that Rick applied for — and won — Ontario Arts Council funding for his autobiographical series Ancestral Mindscapes. A collaboration with photographer Geneviève Thibault and documentary filmmaker Jules Koostachin, Ancestral Mindscapes explores “the intersection of madness, Indigeneity, colonialism, environmental destruction, and the healing power of nature.”

According to the Canada Council, Mad Art is “framed as a social and political identity by people who have been labelled as mentally ill or as having mental health issues.” Mad Art focuses not on awareness campaigns or coping with stigma, but on storytelling, meaning-making, and community-building practices.

Geneviève Thibault, “Childhood Revisited 1 (Dyslexia),” Murdochville, QC, 2018.

“My childhood home, next to the mine my family worked at. While Asperger’s made friendships difficult, dyslexia made communication impossible at times. I didn’t speak intelligibly until I was in elementary school.”

Rick’s “crazy creativity” is not curative but is a means of his survival. His work is definitively not “art therapy.” He does not do art as therapy. He’s an artist first and foremost, and he embraces the fact that his art practice has therapeutic side effects.

Geneviève Thibault, “Miller Mementos,” Sunny Bank, Gaspé, QC, 2018.

“This hints at a century of my family’s mementos. My grandparents raised eight children in their farmhouse. Their grandchildren and great-grandchildren left behind treasures with every visit.”

Rick has lived with mental illness all his adult life. He was a professional editor in the television industry before he lost his livelihood, and eventually his home, to the repetitive cycle of his depression. After a period of hospitalization, Rick rebuilt his life — again. He secured co-op housing and earned a Master of Fine Arts degree from Ryerson University.

Rick also found Workman Arts. Established in 1987 by psychiatric nurse Lisa Brown, Workman Arts is Canada’s longest-running multidisciplinary arts and mental health organization. A theatre company of eight members at its inception, Workman Arts now comprises nearly 500 members. Rick started off as a filmmaking student there and was soon teaching photography classes of his own and working as media artist-in-residence.

Rick finally fit in. “Mad Artists flourish best in community, where we can maintain and sustain each other,” he says. Rick credits his fellow Mad Artists with giving him “the courage to pursue my dreams” and a place he can “call home.”

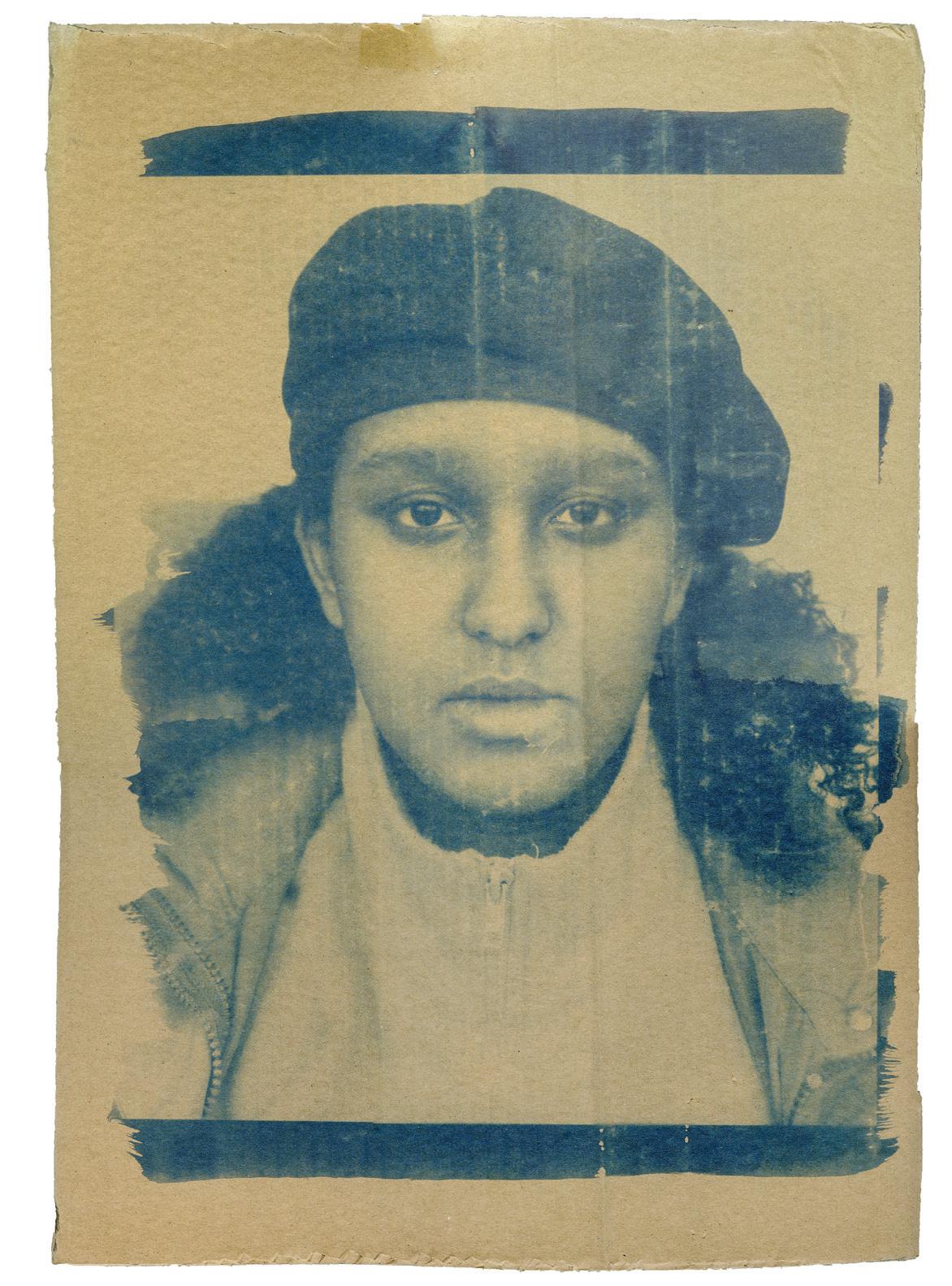

Rick Miller, “I Am Haunted By Waters,” La Chute on the York River, QC, 2018.

“My grandfather and great-grandfather worked as fishing guides on this river. I could feel my ancestral heritage flow through me as I stood by the water.”

Finding a new home allowed Rick to confront his old one. At its core, Ancestral Mindscapes is a return to the home where he was a depressed — often suicidal — kid. Rick hadn’t been home in roughly 20 years; then, in 2014, his siblings asked him to accompany his increasingly ailing, elderly parents to Gaspé, Quebec, for a month-long visit. Ancestral Mindscapes was born with and from this familial journey. Despite the temporal and geographical distances, Rick discovered that he and Gaspé are inextricably connected.

Geneviève Thibault, “Miller Farmhouse At Night,” Sunny Bank, Gaspé, QC, 2018.

Rick, Geneviève, and Jules literalize longing and belonging by inserting and photographing Rick in his old haunts: the old houses and schools, the waterways, and the landscapes of his youth. Far from simple nostalgia, this photographic return is rife with pain and sadness. Various portraits are titled “Childhood Revisited,” but each attaches a parenthetically powerful rejoinder: dyslexia, pareidolia, teenage depression, social isolation, suicidal ideation. Revisiting physical locations entails revisiting mental states — the titular mindscapes — and rendering visible Rick’s “invisible disabilities.”

The notion of “rendering visible” resonates in multiple directions. Rick describes Jules as a Cree artist and seer, saying, “She was our big-picture person, attentive to overarching themes and issues of representation. She has an Indigenous understanding of mental health as opposed to a Western-medical approach.” Jules offered Rick the gift of her (in)sight as he looked for and at his ancestry. Rick says, “As Jules taught me, it’s possible to see mental illness as a spiritual affliction beyond the physical.”

Jules saw the spirit of Rick’s paternal grandmother, Louisa, trapped within her old home (“Miller Farmhouse at Night”). Louisa died before Rick was born, but Jules believes her spirit attached to Rick when he was a teen and manifested as his depression. The challenge now is to help Louisa leave the house in which she’s trapped and, in turn, to let go of Rick. To those who feel that such an explanation stretches the limits of believability, Rick says, “Well, sure. And our co-creator [Geneviève] was thoroughly skeptical, too. Until one week into the project. Then she was fully on board with our unexpected discoveries.”

Rick asserts that Jules’s alternative explanation of his mental illness is “as accurate a diagnosis as I’ve ever received.” He doesn’t concern himself with whether his “ghost story” is implausible or unpalatable to others: it’s a story that he can tell himself about his “self” and why he lives with mental illness. It offers him a new path of understanding and acceptance, and his depression is “less random, less pointless, less debilitating.” Crucially, this “narrative medicine” means Rick feels less lost than found.

Rick’s homecoming inspired a series of interrelated questions: “Who was I? Who am I now? How does my past inform my present? How do others see me?” Rick’s exploration of his personal history and identity (he’s a cis, het, white, Mad man who is also part Métis) inspired larger — and equally fraught — questions about the history and identity of place, particularly about the legacies of his settler colonial heritage. Ancestral Mindscapes includes Geneviève’s intimate portraits of Rick’s return and panoramic landscapes that literally and figuratively broaden the context. Rick is a subject in time and place; he’s also subject to history and geography.

Returning to grapple with (his) ghosts changed Rick’s fraught relationship to “home.” Originally resistant to wading in the water for “A River Runs Through It,” Rick accepted his collaborators’ challenge and now describes this immersion as radically transformative. As “a chubby, bald man” and a photographer, Rick found himself less comfortable in front of the lens than behind it. Letting go of such inhibitions, Rick ended up feeling more “at peace, more connected, and more grounded than ever before.” Paradoxically, letting go was a profound way of hanging on.

Home always beckons to Rick: “I wish I was back there. I’m going to go back there.” Ancestral Mindscapes is Rick’s record and his promise of return.