6 minute read

CHRISTINE FITZGERALD: A FIERCE AND ORDINARY REALITY

CHRISTINE FITZGERALD: A FIERCE AND ORDINARY REALITY

BY BRANDY RYAN

– Donna Haraway, When Species Meet

From the TRAFFICKED series, “Saiga Antelope Horns.”

What do we think about trafficked animal specimens, threatened birds and reptiles, and captive parrots? According to photographer Christine Fitzgerald, we barely think of them at all. Her deeply methodical photography practice thus invites us into a world of tangled dimensions — and encourages us to respond.

Christine Fitzgerald uses now-antiquated photographic processes, such as wet plate collodion, to achieve a printed tonal range that surpasses contemporary printing methods. The techniques in her laborious process date back to the nineteenth century, when photography was just being introduced to the world. This is precisely the draw for her. “I wanted to go back to the origins of photography, the basics,” Christine explains.

After retiring from a career as a health care executive, she enrolled in the School of Photographic Arts: Ottawa. “In the first month, I saw a book of Sally Mann’s work and fell in love with one of the images. I did some research on how she did it, and that’s how I got into historical processes.” Sally Mann’s Southern Landscape series transformed Christine’s view of photography entirely. Christine’s choice of medium and the richness of the wet collodion process make each image seem like it has come from the nineteenth century. Blurring the line between trompe l’oeil and still life, Christine’s TRAFFICKED series takes time for viewers to really take in what they see. Christine was able to get unprecedented access to the facilities of the Canadian Wildlife Enforcement branch to photograph what it confiscates: illegal animal specimens and parts.

From the TRAFFICKED series, “Bear Gallbladder with Bosc Pears.”

In “Bear Gallbladder with Bosc Pears,” the desiccated gallbladder is almost indistinguishable from the pears — until you take the time to really look. “People don’t quite know what it is. They think it’s just a traditional still life of the pears,” Fitzgerald notes wryly. “When they realize that it’s a bear gallbladder, I have their attention.”

Attention is key to the spirit of Christine’s work. She carefully crafts arrangements, light, and texture to blur boundaries between the ordinary and the exotic, the quotidian and the taboo. Numerous photographers document our complex relationships with the environs we inhabit and the animals with which we co-habitat; often, we see these cold, hard realities presented as stark documentary or photojournalistic evidence commanding our attention.

Christine’s fine art approach is more subtle and more emotional. The plumpness of the pears contrasts the withered gallbladder in a complex tangle of exotic animal object and everyday fruit. The ripe pears lean toward the withered gallbladder, as if in sympathy for its plight. Her goal is to make us feel something, to respond somehow.

From the Threatened series, “Leuconotopicus borealis.”

“Saiga Antelope Horns,” on the other hand, has the energy of a lively domestic scene: a table with a set of candlesticks, a wine glass, and a bottle of wine. Inviting and arresting, this image draws us close to stop us in our tracks. Those are not wax candles, but the ringed horns of the male saiga antelope, now devastatingly close to extinction because of human hunting and trafficking. So often these illegal objects are trophies, status symbols. But there are those among us as casual about these trafficked parts as we are about the candles we place on our tables. It is our pleasure and our consumption that drives such violence and desire for possession. We rarely encounter it as it so often appears: hidden in plain sight.

The tension between subjects and objects builds in Christine’s Threatened series, where animal specimens are chosen by her child subjects. These specimens function both as prop and proper co-subject, a common duality in our engagement with the animal world. The pairing of the symbolic future (children) with the threatened past (specimens of whole or part animals) evokes a meeting of species at the brink in the threatened present. Rather than cutely or coyly posing with a token animal object, the children gaze directly, seriously — even confrontationally — at the camera and their viewers.

That gaze encourages us to reconsider the notion of species as its Latin root, specere: to look at, to observe, to behold. “Setophaga petechia” asks us, stoically, to behold how we impact the future of the American yellow warbler, here figured as eggs in a nest. As the young subject gently holds this nest in her hands, I wonder, at what point do the curious, protective hands of children become the indifferent, mercurial hands of adults? At what point, and why, do we regard the animals around us as other, as disposable? And how might a photographer inspire us to hold them in higher regard, to see them in relation with us?

From the Threatened series, “Testudines.”

“Testudines,” also from the Threatened series, gives us a way in — or, rather, a way up, outside conventional representation. Given how frequently we look down on the turtle species and its hard, protective shell, Christine’s image encourages us to see it from a new angle. We look from below, where the turtle’s soft, unprotected belly gives us a fuller sense of the creature’s vulnerability, despite its shell. “When you look at it from the [underside],” Christine notes, “it’s almost as if it has its hands up, saying ‘Stop, stop. Stop doing this to me.’” With 61% of all turtle species extinct or threatened, this is less a plea than an imperative.

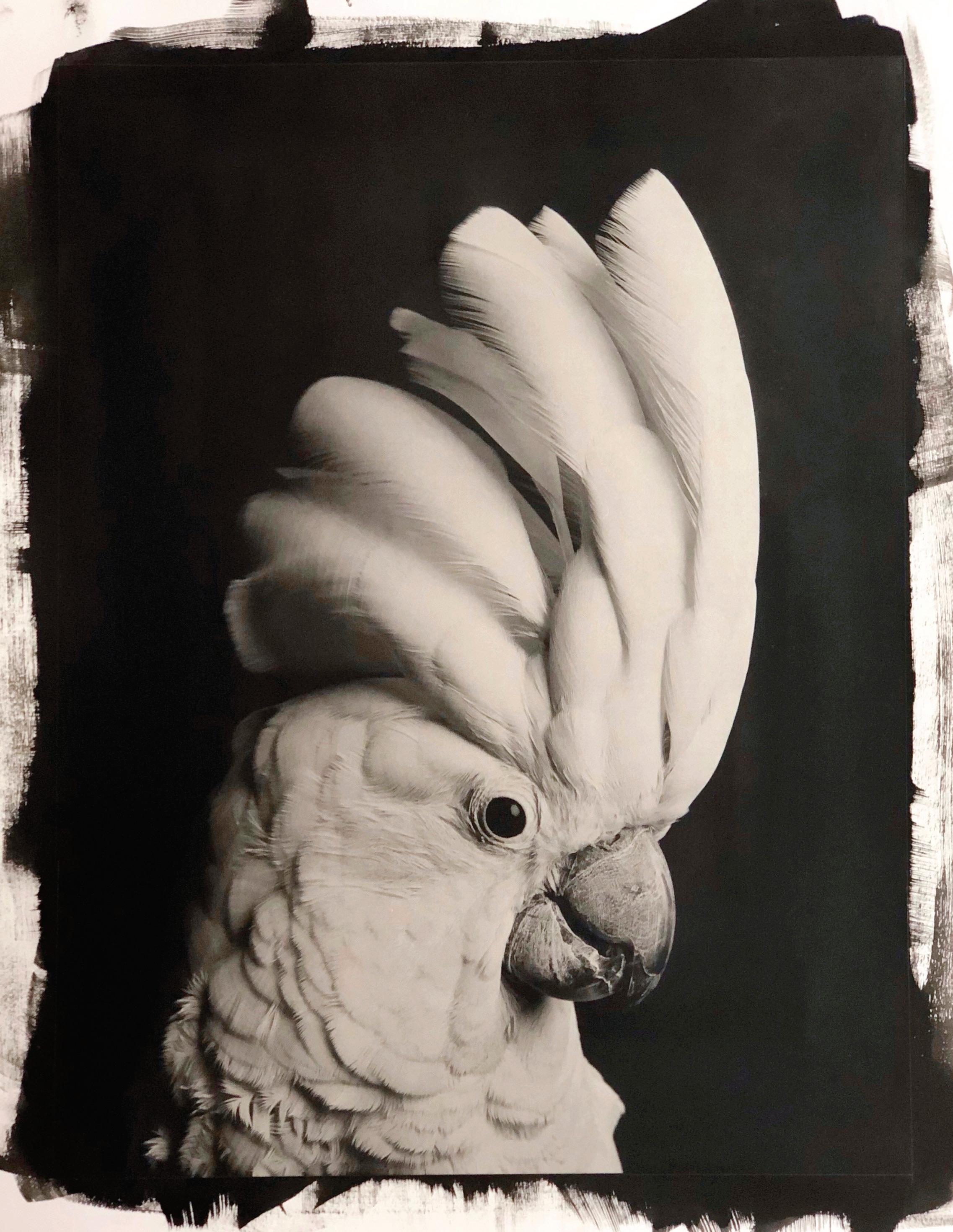

But we’re not just reckless with the trophies of wild animals. We’re also wildly irresponsible with the animals we “own” as companions. Christine’s CAPTIVE series takes us into the world of endangered parrots purchased as pets and then abandoned — often numerous times. “People buy these birds because they’re beautiful and they can mimic human speech, so they’re entertaining. But at the end of the day, they’re wild. It’s in their DNA. People buy them and then they can’t take care of them,” Christine says. Parrots also often outlive their owners (their life expectancy can surpass 60 years). Many are left, abandoned, or given up. “They call it ‘serial relinquishing,’” Christine observes. “They get owner after owner after owner, and they become very distressed.”

To create these stunning, intimate parrot portraits, Christine worked with a handler to photograph the birds in a rehab and education centre outside Ottawa. Parrots are unfriendly to strangers, so Christine spent hours with the birds, building trust so they would come out on the perch she had created for them. Although the birds were photographed digitally, Christine used three different historical processes to print the images: gum bichromate, wet collodion, and platinumpalladium.

Each print is created through a laborious process of trial and error, which takes several days and multiple steps. Christine believes that, without the parrots’ vibrant colours to distract us, we see into their being. The rich tones of her historical processes also lend the parrots crucial gravitas. Parrots are so often depicted as merely amusing and flamboyant, but through Christine’s lens they are subjects in their own right: striking, dignified, and innately wild.

From the CAPTIVE series, “Cacatua alba,” Platinum Palladium print.

It’s tempting to read TRAFFICKED, Threatened, and CAPTIVE as a linear and political trajectory from objectification to subjectivity. We encounter the dead and trafficked objects as still life, the specimen as prop and co-subject in human portraiture, and the rescued parrots as fully realized subjects of their own portraits. But the complex dimensions of these three series hold us even as we behold them, species to species, and the concerns they raise are iterative and imperative. Christine’s images are at once ordinary and fierce, reality and possibility.