5 minute read

LES & MLK

King’s reference to Smith is no coincidence. The two knew each other, and they spent time together. As he continued, one could even hear echoes of Smith’s Killers of the Dream (1949) in his sermon when King described the ways that race prejudice arises from the drum major instinct. He said, “A need that some people have to feel superior. A need that some people have to feel that they are first, and to feel that their white skin ordained them to be first. And they have said it over and over again in ways that we see with our own eyes.”

On multiple occasions, King mentioned Smith as one of the prominent white Southern voices during the period, even listing her, among others, in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail” as one who has “written about our struggle in eloquent, prophetic, and understanding terms.” In “Who Speaks for the South?” King commented that the vocal bigoted minority does not “speak for the South.” Instead, the “voices like those of Miss Lillian E. Smith of Georgia, Mr. Harry Ashmore of Arkansas, and the ever-growing list of white Christian ministers ... represent the true and basic sentiments of millions of southerners, whose voices are yet unheard, whose course is yet unclear and whose courageous acts are yet unseen.”

Twelve years before he delivered “The Drum Major Instinct,” on March 10, 1956, Smith wrote a letter to King. She told him how much she admired his work and how she thought that his approach would be successful. She told King that she would like to have the opportunity to meet him, and she offered her encouragement to the movement. Along with all of this, Smith also noted, as she did in speeches such as “The Right Way is Not the Moderate Way,” the effects that King’s work and the work of so many others would have on the white psyche. She writes for King to tell those in Montgomery, “I, too, am working as hard as I can to bring insight to the white group; to try to open their hearts to the great harm that segregation inflicts not only on Negroes but on white people too.” Along with her assertion of racism’s effects on whites, she pointed out that racism caused a severing within the psyche, causing the oppressor to deny logic and succumb wholly to the mythological ideas of white supremacy that act as an umbilical cord that one must sever in order to truly grow and survive. She wrote to King,

“I, myself, being a Deep South white, reared in a religious home and the Methodist church realize the deep ties of common songs, common prayer, common symbols that bind our two races together on a religio-mystical level, even as another brutally mythic idea, the concept of White Supremacy, ”tears our two people apart.

Smith explored, throughout Killers of the Dream, the ways that these myths created “logic tight compartments” that caused the severing of the mind: “This separation divorced our beliefs from the energy that might have carried them into acts, but we accepted this moral impotence as a natural thing and often developed what is called a ‘judicious’ temperament from believing equally in both sides of a question.”

Smith and King corresponded and met on various occasions. In 1960, after having dinner together, Martin and Coretta drove Smith back to Emory University Hospital for her cancer treatment. “On the way,” as Coretta writes in My Life With Martin Luther King, Jr., “a policeman stopped Martin simply because he had a white woman in his car. Then, when he saw that he was dealing with that well-known ‘troublemaker,’ he issued a summons.” Afterwards, King went to the

DeKalb County courthouse and paid the $25 fine. He was given a suspended sentence and placed on probation. He did not know, as Coretta points out, about the probation.

A few months later, King was arrested during a sit-in at Rich’s department store in Atlanta. DeKalb County officials kept him in prison because they claimed that he violated his probation. The judge sentenced King to six months’ hard labor at the state prison in Reidsville. King’s attorney asked that the judge not send him to Reidsville immediately because they were preparing a writ of habeas corpus; however, in the middle of the night, officers came into King’s cell and drove him to Reidsville, three hours from DeKalb.

John F. Kennedy was running for president against Richard Nixon in 1960. Kennedy called Coretta expressing his concern and telling her that if she needed anything to let him know. Kennedy, along with his brother Robert, secured King’s release, partly as a political move to help secure the Black vote. Some of his advisers suggested against Kennedy getting involved, but Robert persuaded him to do so. As Coretta writes, “It is my belief that historians are right when they say that his intervention in Martin’s case won the presidency for him.” We remember this part of the story. It gets retold, over and over again when we see documentaries or pieces about King or Kennedy. We remember that the authorities kept King in jail after the release of others who particpated in the sit-ins based on a traffic violation from months before the sit-in. What we do not get, though, is the cause for that traffic violation. We do not get that he was pulled over, before the cop even knew who he was, for having Lillian Smith, a white woman and his friend, in the front seat with him. We do not get that he was taking her to the hospital after they ate dinner together. We do not get that the two had a correspondence and relationship. We need that part of the story. We need to see the work that King and Smith did together, the thoughts they shared, the words they wrote to one another. We need their relationship in our memory.

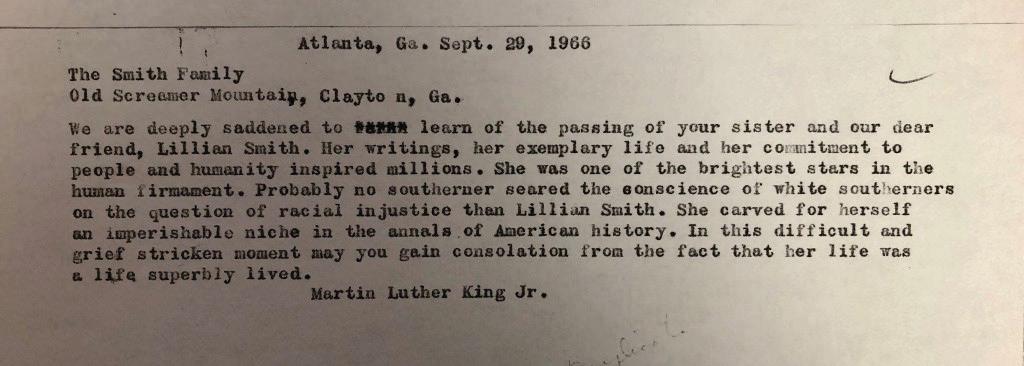

Upon her death in September 1966, King wrote to Smith’s family: “We are deeply saddened to learn of the passing of your sister and our dear friend, Lillian Smith. Her writings, her exemplary life and her commitment to people and humanity inspired millions. She was one of the brightest stars in the human firmament. Probably no southerner seared the conscience of white southerners on the question of racial injustice than Lillian Smith. She carved for herself an imperishable niche in the annals of American history.”

Image of letter

Telegram King wrote to Smith’s family on September 29, 1966. Box 80 Folder 7 Lillian Eugenia Smith papers at UGA’s Hargrett Library.