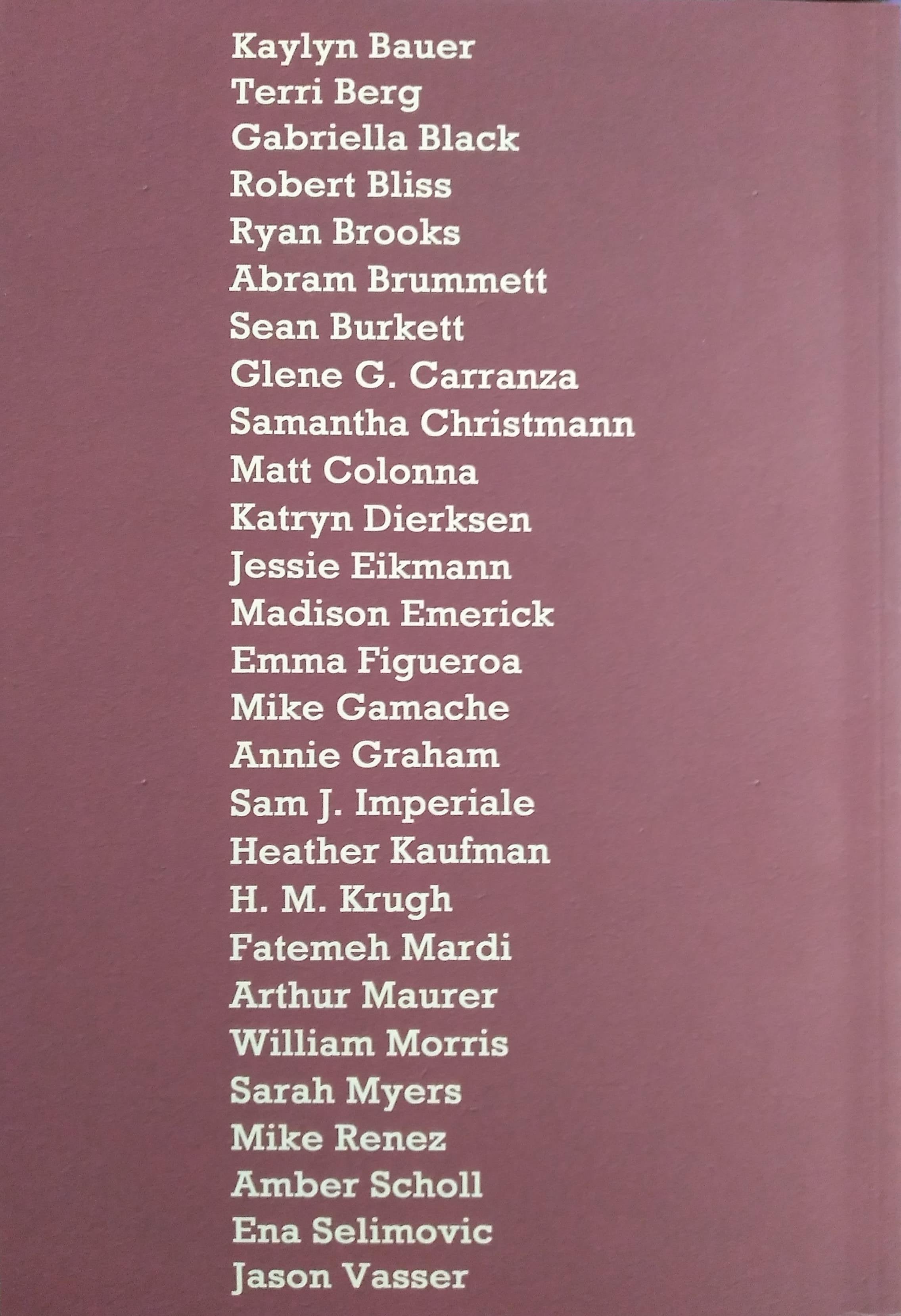

Solipsist

Bellerive 2014

Issue 15 solipsist

1. The philosophical theor y that only the self exists, or can be proved to exist. 2. Extreme preoccupation with, and indulgence of, one’s feelings, desires.

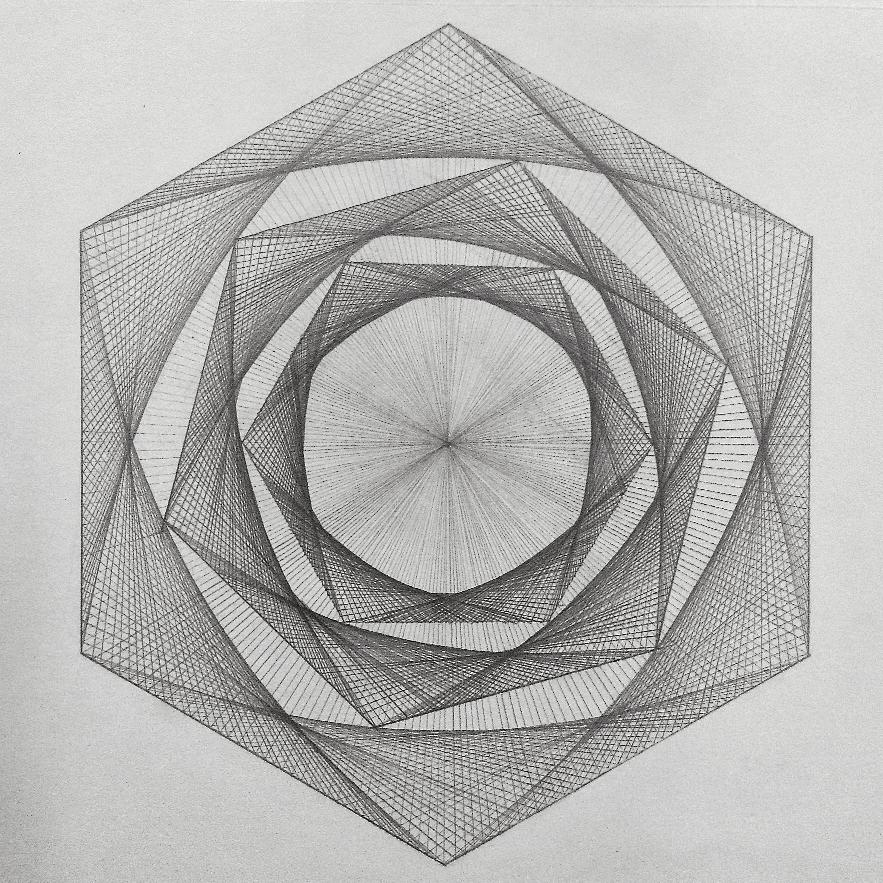

Cover Ar t: Sharp Corner Mike Renez Pierre Laclede Honors College University of Missouri—St. LouisStaff Acknowledgments

Ar t

Ryan Brooks

Emma Figueroa*

Sarah C. Gill

Editing

Peter K. Benoist

Nicole Bonsignore*

Madison Emerick

Samantha Kolar

Benjamin Luczak

T homas S. Mays

Melissa Somerdin*

Layout

K atr yn Dierksen

Marie Kenney

Amber Scholl*

Public Relations

Bekah Cripe

Anna Glushko

David J. A. Niemann

Brian E. Pickens*

Faculty Advisor

Geri Friedline

All members of the staff par ticipated in the selection process.

*Denotes committee chair person

Letter to Tigger, Private Ear

Jessie EikmannW hen you can’t see the w oods Cause ther e ’ s too many tr ees, And you can’t find the needle Cause the hay makes you sneez e . . . Ne ver f ear. Tig ger the Pri vate Ear Is her e. From “Eeyore’s Tail Tale”

After seventeen years, Mr. Private Ear, I have a case for you. Put on your Sherlock cap And patchy cloak. I promise this is the case of your career.

I’m sure you remember Blinking through your magnifying glass At a pair of blue eyes, Blond-headed bowl cut, and Overalls stitched in your imag e, Pacing the public restroom f loor, Imitating your wet lisp And car toonish spring-ste p To ever y unsuspecting patron Of the stalls.

Please find the bathroom actress. Trace the gumshoes back T hrough g roaning escapades, Sweet nothings dribbling from wet lips. Follow the clue: a r usty Sterling ring wedg ed on the fing er, T hen discarded, cleaned of prints. I beg, find the self that can resist Pussyfooting in the gutters.

And promise me, Tig g er, T hat even if you must Plaster the town in cr udely drawn “Wantid” posters or devise an Elaborate trial to convict my libido, You’ll “leave no stone underdone”

Looking for your gig gling big g est fan, Because my nostrils are clog g ed With vulg ar hay, And the trees are blocking my view Of the Hundred Acre Wood.

Maybe the Bonobos will succeed when it all comes to a head, and Africa welcomes Nor th America and Europe to her chest, memories of voyag es lost to the winds the temples will house questions to our writings

as to how communication failed even the wisest of apes, languag es unspoken felt in an embrace.

Perhaps, hiding in the forests where howls will be heard from a distance, there will be sightings of some missing link with answers that will g o uncounted, a member confined to the shadows and to the dark.

He sits

Maintenance

Kaylyn BauerOn the g round with legs spread out Attaching the wires, Working with his hands timid but with the ease of an ar tist.

Sur veying the faces, Colleg e life in naked for m, He sees more than they for the hands of the future g rasp them tightly commanding their attention.

Oak Kitten

Emma Figueroa

Do not aver t your stare as I scamper into traffic for the lone acor n thrown by your branches. And when the tire nearly claims my tail, I’ll pretend I never saw the ill-fated others, later scraped from the pavement for your licks of laughter. Adjust your smirk as I scur r y back into the safety of your knothole, the acor n harbored dee p within my cheeks, where the jeer of your eye cannot penetrate. T he same acor n will fatten me into hiber nation, where I will rest in the chokehold of your boughs until the fr uit of your limbs reg enerates, and I per petuate our morbid ear thy spectacle.

Bar tleby Was a Smoker

Ena Selimovic

Dreams feel real. Last night: my foot on the g as, the seat too close to the wheel, my legs awkwardly slanted. T he car approaches a shar p tur n, but I cannot g et my foot off the g as. Only just before does it edg e its way to the brake, and then only to press g ently. And it is at that point that I see from outside the car, and it looks to be nearly f lipping off the road. But I’m okay. I’m outside. And then I wake, and it’s Friday mor ning, nine o ’clock, and there’s a whole day. All I can think is: Dri ving is m y trig ger for wanting to smoke, that explains the dr eam, and, yes, a cigar ette will be nice.

I don’t know when it happened, but scenes beg an to be reminders instead of what they were, which is experience, or what entailed being present in the moment, what would be italicized in the pag es of self-help guides: Being there. Being pr esent. In the moment. I was anywhere, but her e and ther e were off the g rid (and I vowed never to own a GPS in fear of losing or, at this stag e, g aining a sense of place). W hen a song called “All Your Light” came on, I thought of cig arettes (it was about romantic love, which, in my logic, was still more or less relevant). At the g rocer y store parking lot, a woman said to her whining child, “Is it so ver y impor tant that you couldn’t do without it? Are you happy now?” and I recontextualized it: “Is a cig arette so ver y impor tant that you couldn’t can’t do without it?” Ever y scene reminded me: You can smoke a cigar ette with that thought and w ouldn’t that thought be nicer with a cigar ette? Or : How nice of you to notice X. Now, how about you smoke a cigar ette to tur n of f a bit since you ’ ve been so praisew or thily conscious?

W hen they were sitting unlit in their packs, I felt they would be better lit; as soon as one was lit, I already felt nostalgic that its end was nearing.

T hen, I realized, I star ted listening to my mother, which, aside from ref lecting other more obvious problems related to forever-adolescent pride, made me realize she had convinced me: I was addicted. T his was a kind of, you know, problem, maybe.

If the present was a reminder, the past was a sign. Being aware of the reliance seemed to make me even more addicted, whatever that would eventually mean or, to the outside obser ver, already meant. I star ted looking for the first signs. W hen during lunch one after noon my then-boyfriend Brian said, “T he only reason I would smoke is to be able to say, ‘I smoked once, but I quit,’ and be proud of the fact that I could do it,” I thought, This isn’t going to w ork.

And I meant the relationship. W hat he said about smoking re peatedly resurfaced. W hen he asked what happened, told me we had been happy for months (How many? And had we, really? I felt like I still barely knew him. And anyway, what was there to know about someone? T he philosophical questions did it, right? It wasn’t the passing comment about cig arettes?), I said, “You like to make yourself suffer. You ‘work through’ some stupid experiment, and then claim it as g enuine experience. But it’s crazy, you

realize? W hat do you know?”

T hat g ot him. He was furious. I had never seen him ang r y before. It became clear that it was possible we wouldn’t have been happy, or weren’t really, since he couldn’t be himself in full, as he was now, revealing this ferocity. (I never believed that another could make you better than you were; dee p down you always were what you were.)

“For the record” what record? “ you are the actual smoker!”

“Exactly!”

He didn’t g et it, and I wasn’t sure what I was saying. After a pause, neither of us saying anything, he stopped breathing into his phone and said, “I didn’t tell you: I’m g oing through a lot right now. T his is such bad timing.”

“Isn’t ever ything. Email me. I have to g o. ”

I hung up and thought about how g ood a coffee and cig arette would be out on the porch. And then I did just that, forg etting completely about what’s-his-name. And now I think, maybe, that was the first sign. Severing relationships, being impatient, oversensitive, weighing words all these were in self-help guides. I had become a smoking gun.

Reminders tur ned reminiscences into reg retful patter ns. I heard someone else in the way I lashed out at Brian and knew whose words they were.

It was a couple years ag o. At seven in the evening Jack came over after work in the habit of the time, living apar t but tog ether. I had been feeling ill that day, and dinner was unmade. W hile he showered, I g ot out of bed in the oversized nightg own I had g otten into the habit of wearing, opened the fridg e, and stared blankly. I took a dee p breath. T he car ton of eg gs seemed to stare back, and I slid it onto the counter behind me I scooped a spoonful of butter from the second shelf and, having walked to the stove with the car ton of eg gs tucked under my ar m, shook it into the pan (the nightg own shook with me).

It was just after seven when I cracked four eg gs, watched them sizzle as the colors solidified.

I was plating them as Jack, now in his pajamas, sat at the table. He had a fork in his hand when he paused to ask, “Is there any bread?”

W hen I shot a pitifully annoyed look at him, he quickly apologized and said, “I’ll g et it,” but I was already by the cupboards on the other side of the island.

I opened the cupboard next to the fridg e and g rabbed the loaf, cut three slices, and placed them next to his plate.

He quickly forg ot I was ir ritated then and beg an eating.

I went back to bed, tr ying not to notice how loudly he ate.

Ten minutes must have passed when I decided to g et up ag ain. It was clear an argument was set to begin from the star t of the conversation, but it came to full potential when Jack said, “It’s nothing you want to hear.”

I answered, “I don’t know if it makes sense in my head, but I’m relieved.”

Following a quick “W hat?” he looked up from his meal, his fork still

raised.

“It’s women. T here’s another woman. It isn’t your health or family troubles or finances. Anything that matters. I mean, it’s not like we would’ve ever worked out, anyway. We hardly know each other. But anyway. ”

“How do you know that?”

“We’re different. You always wander, and I don’t.”

“You’re full of shit.”

“We barely talk anymore, anyway. I’ve always been ter rified of that. Not having anything to talk about. You know? You see those couples in restaurants and ever yone mentions them. T hose couples who don’t talk anymore. T hey’re even mentioned like this by couples in films who are scared of becoming those couples. You know? And that’s what happened with you and me right at the beginning. I mean, look at this nightg own. And you’re eating eg gs for dinner.”

He was eating ag ain, but slowly, looking up at me between scoops.

Fearing there would eventually be no eg gs left on his plate, I continued, “You were there until you realized the feeling was mutual. T hen you were g one. It was enough for you. I know how it g oes. ”

He remained silent at first, then re peated, “You’re full of shit,” his mouth half-full. He looked down at his food ag ain.

“T hat was just the beginning for me. But it was already over for you. Women.” I remember scoffing with a smile. It didn’t feel like me, like something I would do. I didn’t know what it meant.

“You don’t know anything. W hat do you know?” he had said.

I paused. “Anyway, I hope the eg gs are g ood.”

He broke the silence ag ain, saying, “I actually have to g o back to work in the early mor ning. Inventor y stuff. I thought I’d stop by. I wanted to tell you it didn’t work out between me and her.”

I continued looking at him.

“I thought you’d be happy,” he added.

I didn’t know what to say. (At first, I was distractingly annoyed by the way he held his fork with his right hand in a fist.) I felt like I had cheated someone out of a potentially positive relationship, when I had nothing really to do with it, and when it tur ned out not to be, according to him, positive at all. So I said the only thing I could think of saying: “Well, it isn’t like I ever wanted you to be sad.” W hich was tr ue.

“You’re difficult. Anybody ever tell you that?”

I went back to bed without responding. Or that was my response. I had already quit; it took me nine more months to realize.

W hen he entered the bedroom, he was loud enough that I could pretend he’d woken me when in reality I found slee p taxing, because remembering was the only activity my body seemed to will itself to do, and memories embodied phantom pains. He had no way of knowing, anyway; I was lying on my side, my back to him.

“W hat’s wrong?”

I didn’t answer. I wasn’t ready for what was inevitably g oing to

happen now. I didn’t understand why he had to confront me. I wasn’t feeling well, after all. Perhaps I hadn’t been feeling well for a while. W hat did he know?

I looked to the right with my eyes, as if they could roll back and see, without being noticed, his slightly lifted head, looking at me.

“So? W hat’s wrong?” Hearing nothing still, he implored more ster nly, “Louise.”

I said, “I’m sor r y. I haven’t been feeling well.” W hich was tr ue.

He r ustled to his side, his back to mine, and jolted his half of the blanket.

T hen the car alar m went off.

After five minutes, Jack muttered, “You have g ot to be kidding me. ”

He resituated the blanket, par tly uncovering me, and covered his head with his pillow.

W hen another five minutes passed, I sug g ested it was his car.

“It can’t be. Mine doesn’t sound like that.”

I mouthed, bobbing my head sideways, Maybe it is. W hat do you know? You don’t know anything .

I threw my par t of the blanket to the side and swung out of bed into my slippers.

“I’m telling you, it’s not mine.”

“Well, if it isn’t, I’ll at least see whose it might be.”

“T here you g o ag ain. W hat’s it to you?”

I didn’t want to be in that room with him. W hat was worse, I wasn’t sure why. All this happened quickly. T hen I retur ned to being there, in this then-present moment which required that I react to Jack’s snide remark I stopped at the doorway and tur ned back to look at him, but it was too dark and I couldn’t tell if his eyes were closed. I wished he could see my look. I didn’t want to talk.

I shr ug g ed and proceeded to the next inevitable par t of the scene. But then I couldn’t find his keys. He usually left them on the island as he came in. Still, it didn’t matter. I knew he knew his alar m better than I did (how many times had I heard it in two years?), that it wasn’t his car, but this wasn’t about the alar m anyway. So the faux search pretended to aid results.

T he alar m stopped before I g ot to the front door. I thought I heard the next-door neighbor shutting the door of his house. I retur ned to bed.

“And? W hat did Detective Huffing puff find?”

W hen tr ying to be playful, he was always cheesy ir ritating even (more than his style of fork-holding). Maybe he reg retted what came before. All of it. Maybe I did too. I hit him with my pillow before settling back into bed, unsure whether I would use the g esture to lighten the air or whether there was really no g oing back from what was happening, or would happen.

He laughed, and I then quickly decided: “It was yours,” I said.

I still had my back tur ned to him, but I could feel a chang e; I could see him raise his head and look at me. I reg retted then. I felt heavy. I wanted to sink into slee p.

Instead, I re peated, “It was yours,” feeling his continued challenging g aze. It was all too simple: I had already given up, and he wouldn’t stop me.

“It couldn’t have been.”

“Are you g oing to slee p, or what?” I had no idea what I was doing.

He g ot up. W hen he retur ned to the bedroom, he had his coat in one hand and the keys dangling in the other. I was relieved; I thought he was leaving, but then I remembered this scene revolved around a car and that the keys might be relevant.

Sure enough, he said, “I had the keys the whole time. How’d you tur n the alar m off if it was mine?”

His wanting to prolong the argument ref lected how we had been these past few days weeks? (How many?)

“Now you can’t stand being wrong about a damned car alar m?”

I didn’t want to argue anymore.

“Exactly! Let me slee p already.”

He left the blanket with me, but when he retur ned ag ain, he took his pillow and sle pt on the sofa downstairs. I had a hard time falling aslee p. I ke pt hearing the alar m. I ke pt hearing Jack say, “W hat do you know? You don’t know anything.” I wanted to ask him if there was somebody else still, if it was working out, if he wanted me to make some eg gs, knowing he had already eaten, knowing he would say there was nobody, and then to tell him, “I hope the eg gs are g ood.” T hat was all I had hoped for, and it wasn’t enough.

Ever ything came tog ether in a ball of smoke emitting from my mouth, knowing I was addicted, and I felt without within and pr esent, ther e, in the moment at least until the end of that cig arette and the beginning of the next T he in-betweens were hard, but they were hazy anyway. T hings had come to pass, and it didn’t matter what I knew. For the first time, I found something simply ir resistible. I put the kettle on the stove, retur ned to the porch, and thought, I am happy. It is so ver y impor tant that I can’t li ve without whate ver makes me so. I hoped I would have the same dream ag ain that night.

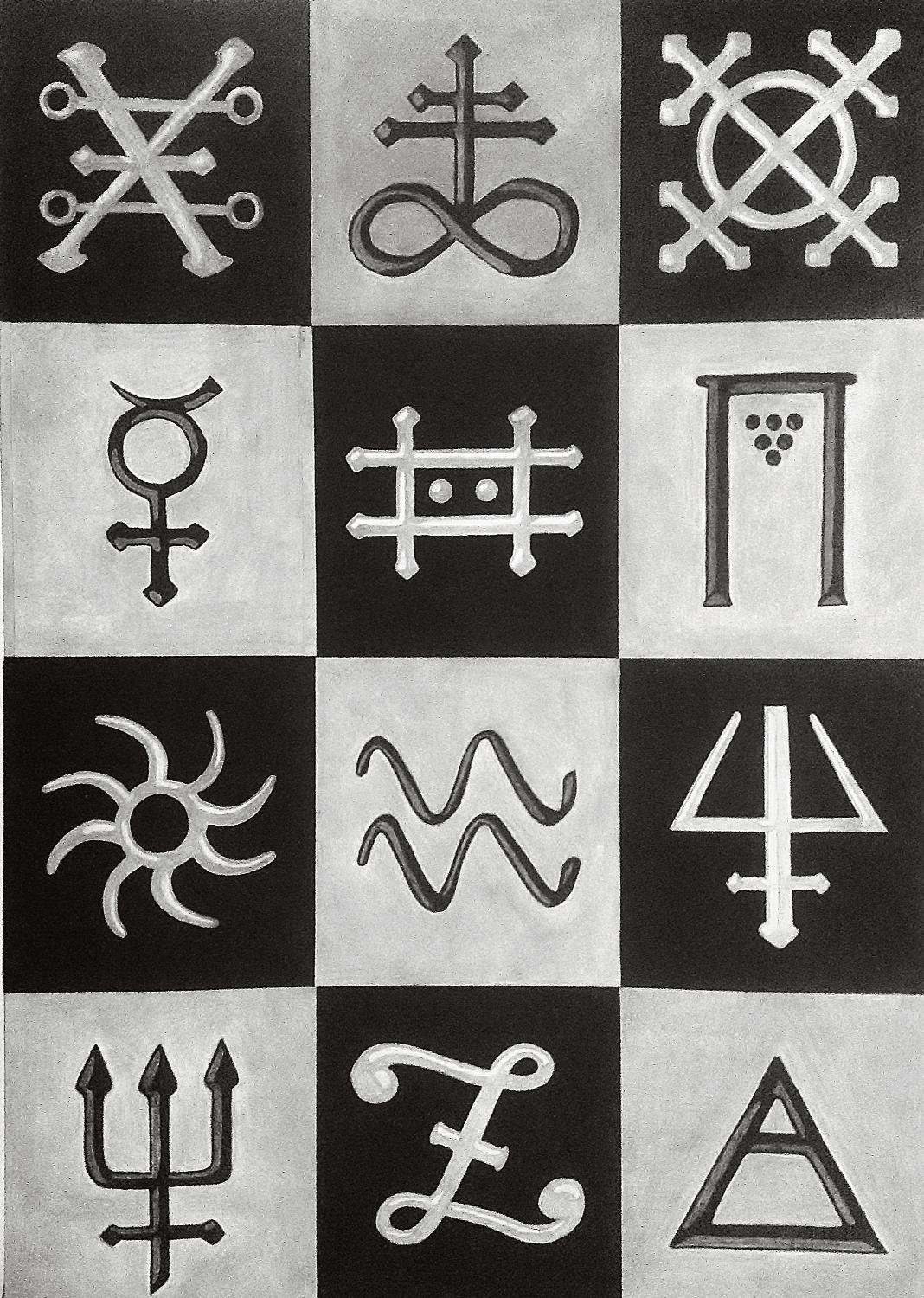

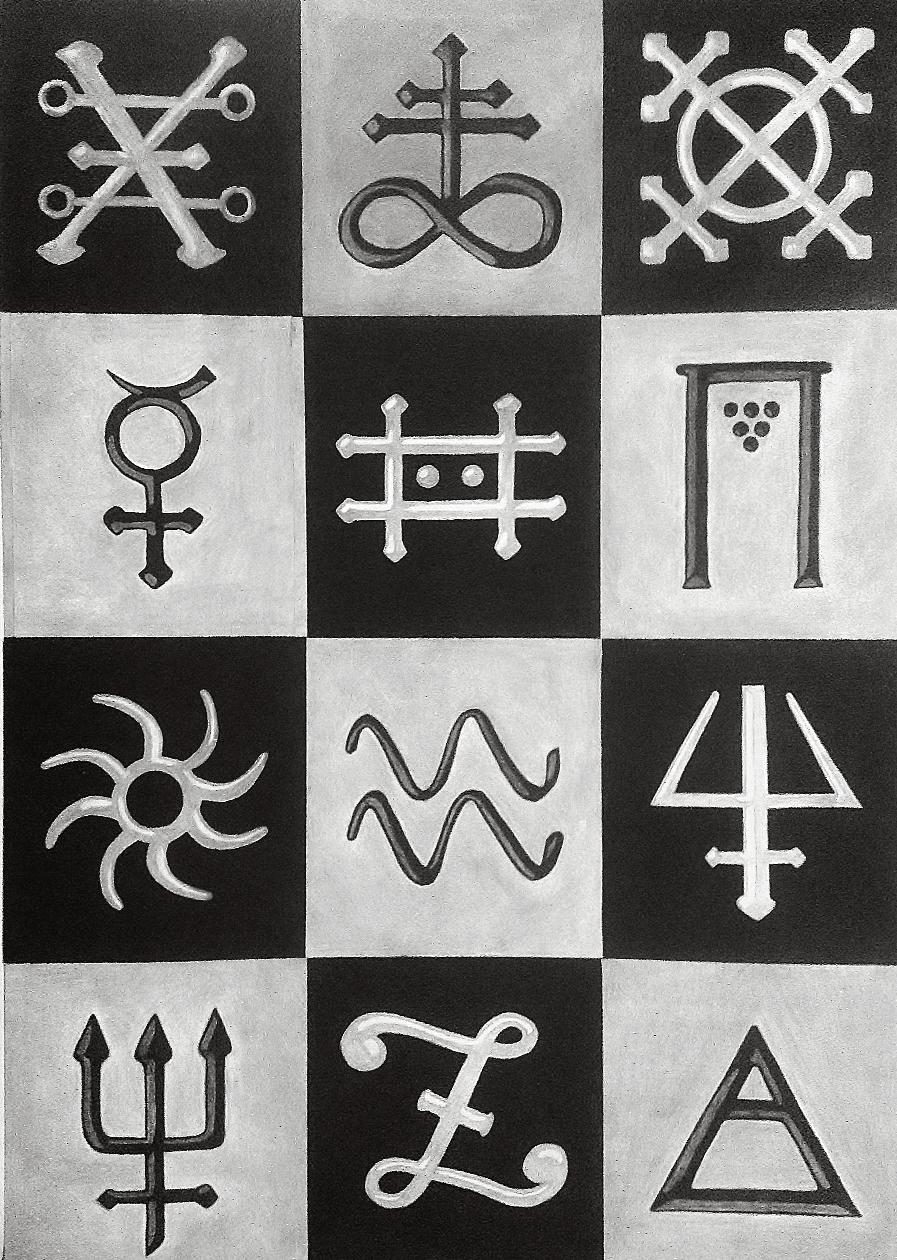

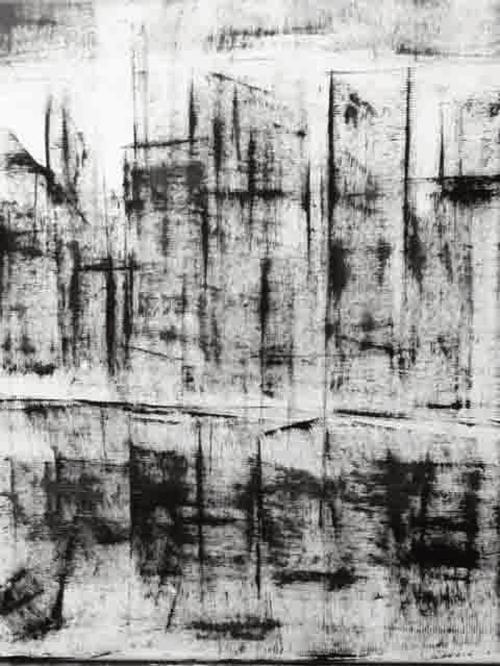

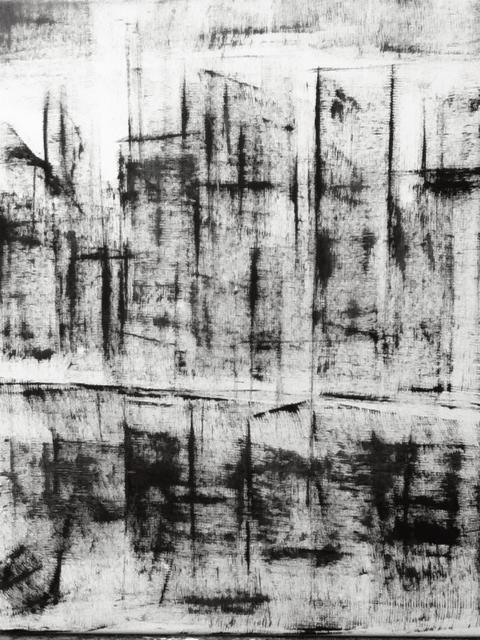

Matt Colonna Alchemy

Parietal Galler y

Jason VasserWe star ted our descent into the cave for par tial fulfillment of coursework with fear of the unfamiliar darkness that awaited student anthropologists on our first time below, where the light of the sun has not reached for thousands of years, where there was dampness and quiet, save our chatter and professor’s instr uction.

I had developed a love for oil over acr ylic, the ways in which the br ush made the paint move smooth as skin at my attempt at profiles emulating the Eg yptians, but today, I thought that my steady hand would preser ve relics unseen by human eyes since our ancestors lived here among the rock in a time before antiquity,

when a poem might have been a series of g r unts sung by the light of newly lit fire. We looked around for hours, and after a while I was drawn to an almost shadow, a palm centuries old, a signature to animals painted in landscape as extinct as the hands that created this work of ar t.

With these hands, I traced lines of an ar tist forg otten by the world denied its g enius in stroke after stroke, in shading and contrast, in a for m almost lost to us that at last has been found by a fellow ar tist, kneeling in awe.

Buttermilk Waffles

Emma FigueroaSweat beads slide down my neck as I thr ust the spat back and for th across the stick y heat.

Dinner and a Show. Sure, I’ll fulfill the promise of my f lair.

Mustachioed by milk, they eat potatoes dressed in chili, fried to their liking by my blistered hands.

Bleached water splashes around my legs as I ride this wave of g rease and eg gs, deck br ush in hand.

W hy make use of buttons? My mother taught me how to use my anatomy.

And maybe I’ll delude them to achieve what I year n for : another dollar for my tank, maybe two towards my soul.

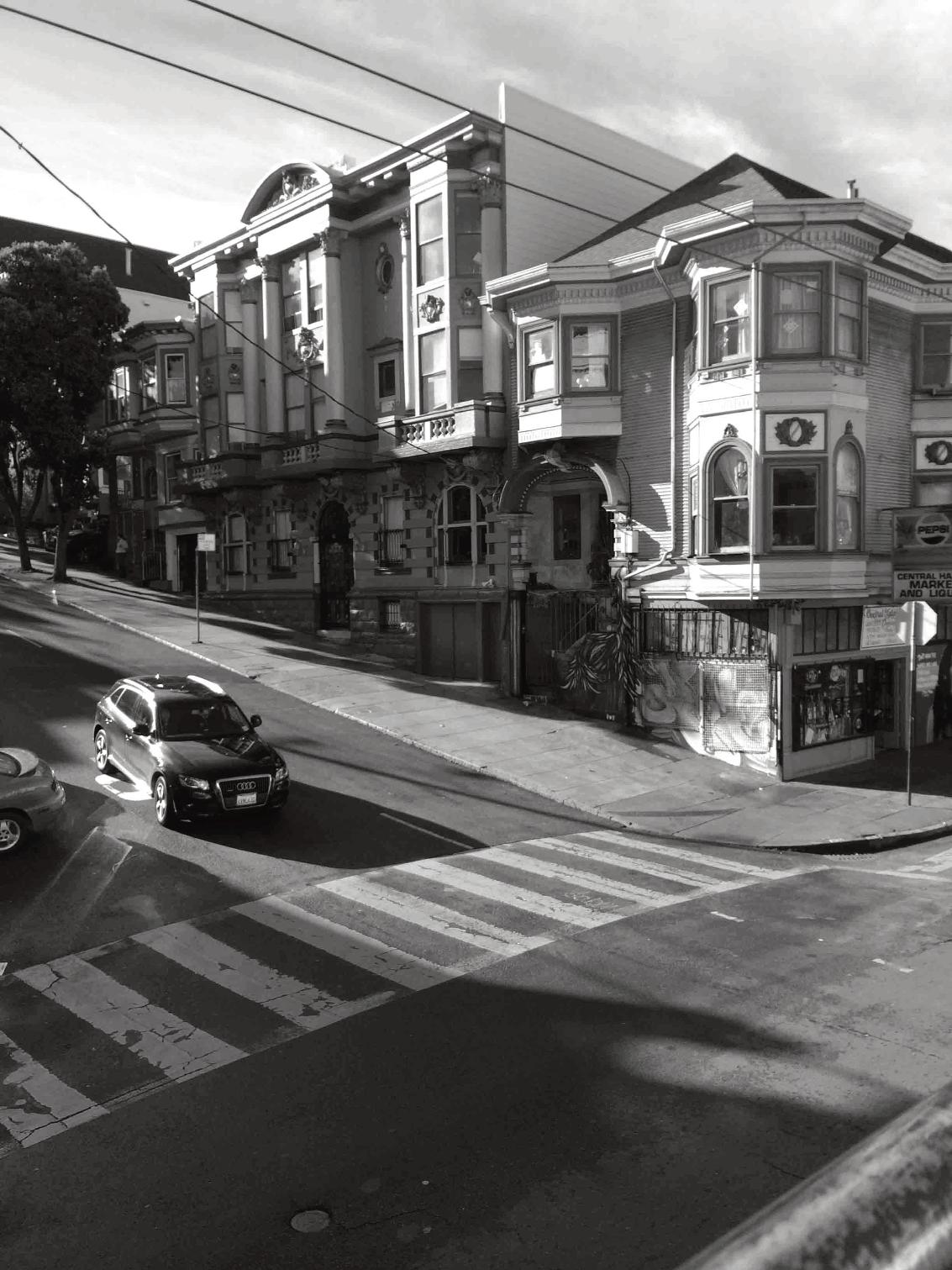

The Voices in the Carpet

Sam J. ImperialeT he brick-framed windows on darkened upper f loor peer as g raying eyes with glass pane irises. Dir ty lace lids frozen slee pily open, stained brown from cig arette smoke cast shadows on the silent walls.

Lifeless ivy remnants still cling, hang as faded g reen necklaces on cr umbling reddish throats. Dollhouse entr y looks like lips tur ned down, frowning now without kisses, her last touches tor n by eter nity.

Cactuses in dee p comas ador n her ankles, thor ns stretched out as defiant lances, soldiers shocked and sliced by winter’s knives. Jag g ed rocks have become stony pillows for slee p. Summer buds slipped away slowly, pleading for life-giving g raves in the g round.

Stunted stairs strain to possess a small bar ren plateau overlooking the street. Rusted thrones cast empty shadows on the peeling landscape. Handicap signs mark in blues the borders of this decaying dream.

A ding y brass mouth once swallowed messag es, and a Cyclops’s nose handle hammered out heralds. Hollow eye used to spy on the homes across the street. T he kee per of the key has come to close this chapter and bur y his burdens. I unlock her hear t and lower the veil.

Tiny impressions speak as ghosts of “sofa and chairs, ” the many bur n marks mur muring “Mom, ” silhouettes of “Sister ” whispered by throw r ugs f lung, scraps of “Dad ” talking from the tor n holiday cards. T he stains spills sour smells star t screeching and screaming “Listen to us! We ar e the voices in the car pet.”

Hillslide

Kaylyn Bauer

Kaylyn Bauer

Don’ t Take Things for Granite

Sean BurkettInner core

Outer core

W hichever core you are You’re smokin’ hot.

Subduction is seducing

Faulting is fun

And your cleavag e is better than your crevice.

You be my layer of hot, solid material I’ll be your layer of rock for ming on top.

We can infiltrate, meander, and r unoff tog ether.

If you mix your intr usive with my extr usive we will surely be tuff.

You make my hear t par tially melt You are the hot spot to my shield volcano

T hough you luster in light you’re as hard as a diamond.

Metamor phically speaking Schist happens

But if you date me I’ll make your bedrock.

I feel like I need to be mentally pre pared before I look at “my face” in the mir ror because, at my ag e, I know my parents will be staring back at me. W hy is it that we seem to inherit the worst traits of our parents? W hen I was young, I swore that I would never look or act like them, but time and that undeniable face in the mir ror say otherwise. It must be God’s little joke on us to have those insidious chromosomes working under the surface, tur ning us into hideous mutations of Mom and Dad. I g ot Mom’s sag g y jowls and chicken neck, which I used to make fun of. I am cursed with Dad’s bags under his eyes, which made his face look like it was melting. I also have his shor t legs, which means that ever y pair of pants I buy has to be hemmed. W hen I wear a suit and hat, I look like the car toon mobster from Looney Tunes, who is mostly torso. My wife thinks I am having an affair with the local seamstress because I am over there so often, g etting some appendag e of a g ar ment shor tened. “T here must have been a g r umpy Sicilian troll somewhere in my lineag e, ” I always mutter into the magic mir ror.

My stomach seems to have skipped a g eneration. In that reg ard, I am built like my g randfather, who was shor t and stock y with a round potbelly. I always wondered why he wore suspenders until I found out the hard way. W hen your belly is big g er than your hips, there is no place for your pants to g o exce pt down. T hus, the suspenders! After my pants fell down at my daughter’s wedding, I star ted wearing them too, as insurance ag ainst Sudden Ass Exposure Syndrome. I picked up the bad habit of g oing “commando style” in the Marines, so falling trousers can be especially embar rassing for both witnesses and the victim.

Oh! And let’s not forg et the mannerisms I also swore I would not have T here was no doubt that my dad was Sicilian because he, stereotypically, talked with his hands and, many times, with his whole body. T here were the facial expressions, too. I can’t help making them as well. I like to think of it as a for m of ethnic sign languag e that became imprinted on my psyche. In layman’s ter ms, it was monkey see, monkey do only it was a Sicilian monkey.

First, you have to have a per petual scowl on your face. Sicilians are not supposed to look happy under any circumstances. My dad’s scowl made him look like Moe from The Thr ee Stooges. Me, on the other hand, I look more like Steven Van Zandt from Lilyhammer : a frown so dee p that the ends of my mouth look like they are touching my collarbones. If I am happy, the frown tur ns into more of a smirk. My smile looks like a dog g rowling out of the side of its mouth. If I scowl in the mir ror, I cring e in hor ror because my dad is looking back at me. I always thought my dad was g r umpy all the time, but I know now it was par t of a Sicilian tradition.

Head movements and facial expressions are a sign of how a Sicilian man is listening. If my head moves in a rapid but shor t “ yes ” motion, it

indicates that I am listening to you, but I can’t wait until you shut the hell up. If my head moves a little to the side at the same time, it signifies that I may not like what you are saying, but I reluctantly ag ree with you. If my left eyebrow is raised higher than Mr. Spock ever thought possible, it means I am per plexed. W hen my eyebrow looks like a pencil sketch of Mount Everest, I don’t believe a word that you are saying. If I roll my eyes during any of these motions, then I am tr ying to ignore you entirely.

Let’s talk about hand g estures! A Sicilian man ’ s ag g ravation level can be measured by how far his hands raised above the waist. If my hands are slightly above the waist, palms up always palms up I am a little ag g ravated. If I am shaking them at the same time, I would like to know why you are ag g ravating me. If my hands g o over my head, you have really pissed me off. T he most intuitive of witnesses to this g esture know that they should r un at this point. Slapping my open palm on my forehead means that I realized I was par tly responsible for the ag g ravation. T his g esture should be seen as somewhat of an apolog y. T he slapping of the forehead may be confused with the “aha” moment or a “senior” moment, so close obser vation is necessar y to differentiate. And never make the mistake of asking me to tell a stor y someone might g et hur t! Just like Dad, my whole body will be moving violently ever y which way, with my ar ms f lailing in ever y direction, tr ying to act out ever y word. I once tore a rotator cuff in my shoulder and threw my back out while describing two ele phants making love in an elevator.

Sicilian men can car r y a g r udg e for a long time, but they do have the capacity to forgive. Placing my elbows on the table with my hands tog ether, as if I am praying, symbolizes we are about to talk about something you have done wrong If I rock my hands front to back, that means I am willing to forgive. Touching my hands to my forehead signifies that you are shor tly taking a one-way ride. If I place my face in my hands, it means that I like you, and I am sor r y, but you are still g oing down for what you did. By placing my hands on my chin, I mean that I need a minute to consider your fate.

I shr ug my shoulders mostly for answering questions. A slight shr ug means, “I don’t know.” A more pronounced shr ug indicates, “I don’t know, and I don’t care.” If I raise my hands up above my waist while shr ug ging, it means, “W hat the hell are you asking me for anyway!” For the worst offenders of my personal space, I will leave my hands at my sides and clench my fists. T his means I am plotting reveng e ag ainst you, and I just have two things to decide: when and how. W hen Sicilians see this sign, they usually join the Witness Protection Prog ram.

Hair is not the friend of a Sicilian man or woman. It always seems to g row where it is unwanted or unsightly. Looking closely at my face in the mir ror usually entails a glance at the nasal cavities for the er rant nose hair. Getting rid of nose hairs is harder than it sounds. I tried one of those electric nose-hair trimmers. It g rabbed an especially thick hair, jammed, tore the machine from my hand, and nearly ripped my head off. I had to yank the cord out of the wall to save my life. Now I do it old school. I g rab the end of my nose and yank it in all directions while hacking at the little bastards with a

tiny pair of scissors. T hanks, Dad, for the Sicilian hair g ene!

My mother had an old wives’ tale about hair. She would say, “Men with hair y butts are g ood at raising pigs.” Thank God I can’t see m y ass in the mir r or! Well, I used to be able to, but if I tr y it now, I’ll pull a muscle. I do know that I am pretty g ood at raising pigs, though. I raised six: two boys and four girls. I named ever y one of them, too! I wasn’t sure they were pigs at first, but when they became teenag ers, one look in their rooms confir med my suspicions. It was impossible to deny they were mine: there will never be the need for a pater nity test. All they have to do is scr unch their faces into a scowl, and it ag es their looks, which tur ns both the boys and girls into instant “Mini-Mes.” Ever y time we take a family photo, I tell them to scr unch their faces in unison. We call it “T he DNA Test.” It proves beyond a doubt that we are related.

My parents and g randparents are all dead, but when I look in the mirror, I swear that I can hear them laughing. If I have two mar tinis before I look, I will laugh along with them and then practice all of Dad’s mannerisms to make sure I am doing them cor rectly. I always end my bathroom routine by saying, “Mir ror, mir ror on the wall, who is the g r umpiest g eezer of all?”

Gingerbread in Early Winter

Jason Vasserafter Rober t Frost

Life was too much like a pathless wood, hounds in the distance and the sounds of chatter from those in chase, not for the body so much as for the will to leave a place destined to kee p the mind in a steel box: letting the sun inside with its heat, leaving no room for shadow.

The Television Episode

Jessie Eikmann1

Pr e viously on this show

Booms the announcer

As father and daughter bicker in montag e, Raging pantomimes pointing, Stomping, their lips staging Syllables in hyperfocus. Up from the g arble of voices

Rises her resignation: “Fine. You use T he television. I don’t want to.”

T he imag es vanish

From the new 60-inch f latscreen. T he shot slows, Stumbling toward the close

Of the recap.

Her hand lobs the remote to the couch. His face freezes. T he transitional Cymbals clash. T he screen g oes se pia.

2

In the dying notes of theme music, Floodlights g o up. Time and color resume, T he father’s eyes nar row, his face pur ples.

“WHAT DID YOU JUST DO! YOU FUCKER! YOU DON’T THROW MY SHIT, UNDERSTAND ME?”

She sighs, takes two ste ps stag e left. He blocks her. His spit clings

To the camera lens. “YOU WALK AWAY AND I WILL PUNCH YOU UPSIDE THE HEAD! I’LL SPEND THE NIGHT IN JAIL! I DON’T CARE!”

3

T he scene re plays in ever y room

Of the set. He circles the kitchen table. He pounds on the basement walls.

“DON’T YOU EVER TOUCH MY TELEVISION AGAIN! HEAR ME?”

She is cor nered between him

And the bathtub. He yanks her hair.

His other hand is hovering. He recites

His cue cards of threats until

T he camera shifts, And the daughter’s eyes

Edg e around the father’s shoulder.

T he sound guy is missing. She smashes the mute button in vain.

4

It’s dark. T he set is quiet.

T he camera pans on the f latscreen, Switches to the daughter’s face, Flatscreen, daughter ag ain.

T he picture leaps behind Her puffy eyes. Piano music

In minor announces

A series of blur r y frames:

T he father hug ging the f latscreen, Eating across from the f latscreen, Driving his car with the f latscreen

riding shotgun, tucking the f latscreen’s Massive frame into bed.

5

T he shot recr ystallizes.

T he daughter’s head is in her hands

T here are no end credits.

Str ung like an aristocrat, I waltz down the halls, hands in my coat pockets, eyes that see through the walls. Madman’s eyes. Godzilla’s tread. I retreat fur ther into myself, into the hell of myself. Exhibit A, madames et monsieurs : a broken toy.

“Does it squeak? Does it sing? Will it dance if I pull the string?” Oui, oui, mes amis : and a wicked glare, peanut shells for eyes and a broom of chestnut hair. Take a look into its soul, it’s five dollars a stare: a ter rible, vacuous thing lies there.

Dr. J & Mr. H in Isolation

Samantha Christmann

Quite Some Time

Abram BrummettWe puzzled and pined and thought we knew T hat to fix our problems we need divide the world in two But if then two, then why not three? T his could g o on for quite some time, you see

If a world needs another to solve all the problems Of ethics and pur pose and origin and knowledg e T hen the source world must be a troubled, cold, and lonely place An inevitable sadness, despite not existing in space

Btu waht fi ew fnoud our qusetonis colud be resolevd By raelzinig we wree not bulit, but evolved T hr uogh blindenss and trial and toil and might We beg an to say “ought,” “injustice,” and “right”

And we called things “ g ood” not because they were tr ue But because they were loved, and love g ot us through Yet it wasn’t all kindness, there’s plenty to dread T here’s a heaven and hell in us all, it’s been said

Celluloid

William MorrisT he f lur ries caressed my f lesh like a schizophrenic fing er tip’s cer tain touch trembling, tur ning cold and callous, then quickly melting ag ainst my cheek.

The Pain of Pancakes

Amber Scholl

Oh so carefully, Derick measures out the f lour. T he baking powder. Accidentally adds a pinch too much salt, which essentially means the entire batch has been r uined, and he has to star t ag ain. Flour. Baking powder. Salt. Sug ar. All perfect, precise, each ing redient measured exactly and lumped tog ether in a lime-g reen bowl. Derick g oes about melting the butter next, selects the best three eg gs from his fridg e, then beats the new ing redients into the powder y, g rainy white mix. Not until he opens the topmost cabinet and finds it lacking does he realize his dilemma.

T here are no chocolate chips in the house.

Five minutes later he is bundled in coat and gloves and scarf, ready to walk out the door. It’s a chilly Sunday after noon the kind with unforgiving g ray skies and wind that cuts through clothes like dag g ers; Derick g enerally avoids g oing out on such days. He stands at the doorway, braced between the safe, knowable world of his apar tment and the elusive one beyond. T he distance from his building to the store is roughly 500 million light-years. Entire g alaxies, planetar y systems, and soul-sucking black holes litter the path between the star ting and ending points, or at least that’s how it feels. Time stretches on; it is still and quiet enough that if he listens closely, he can hear his watch ticking the seconds away. Sweat r uns in rivers over his face. His hear t pounds like a wayward dr um ag ainst his ribcag e.

Derick wouldn’t bother at all exce pt that she is coming, and coming soon. Pancakes, especially the chocolate chip kind, are at the top of a ver y shor t list of foods she considers acce ptable. If not for her, Derick would happily shut the door on the outside world.

Finally, after several moments of tense deliberation, he sticks his foot outside

Nothing happens.

Another ste p. His shir t is sticking to his back. Down the stairs. His shoulders ache from holding them so stiff ly. He manag es to make it completely out the door before his chest tightens up and robs him of oxyg en. Ever since the accident, this panic has been par t of his life whenever he ventures outside the apar tment. He’s lear ned to live with it. Mostly.

He blunders forward, gulping air and forcing icy breath inside his bur ning chest. It takes a few more minutes down a deser ted alleyway before he reg ains control.

Slipping his way along icy sidewalks, Derick picks his way across several snowy blocks. T he sk y is a wintr y g ray, and the sun shines weakly. Occasionally, a car drives past, kicking up blackened sludg e in the wake of its wheels, but Derick passes no one else on the sidewalks exce pt a scrawny stray cat. At last, he finds himself on the slushy pavement of the g rocer y store parking lot. T he double doors of the building welcome him with a sudden r ush of war m air.

He maneuvers as stealthily as possible between the store shelves, avoiding contact with ever yone who comes near him. He waits patiently, his skin g rowing hot beneath his heavy coat, for two women to finish their conversation and remove their car ts from the middle of the aisle he is attempting to walk down. Finally, they notice him standing there and move. Derick scurries past them, his eyes glued to the shelves full of baking ing redients.

T here are four brands of chocolate chip bags in front of him. Slowly, deliberately, Derick reaches out and picks one up. Weighs it in his hand. Puts it back. He reaches for another, a bright yellow bag, and shifts it from palm to palm. K atie’s favorite color is yellow. Yes, he feels sure yellow is the way to g o.

Cradling the yellow bag in both hands, he heads back up the aisle where the two women are still talking, their car ts now parked on either side of the nar row space like some bizar re g ateway. At the end of the aisle he pauses, tilts his head; there is a display of colorful f lower-shaped pinwheels ar rang ed in a brown cardboard pot, a sight quite at odds with the wintr y scene outside. T here’s one with a g reen stem and yellow petals.

He plucks this one from its cardboard pot and makes his way toward the front of the store ag ain. An elderly man br ushes ag ainst his shoulder on his way up the aisle, making Derick jump backward into the display of dog treats behind him, which cascades to the g round.

“Are you okay, son?” the man inquires, pausing in the act of choosing a bag of cat food from the shelf.

“I’m fine, thank you, ” Derick stammers, hur riedly stacking the dog treat boxes back in their original positions.

“Maybe you should sit down You don’t look too well ”

“I’m fine, thanks,” Derick says ag ain, not looking at the man, his focus on re-stacking the boxes with one hand. His other hand is still clinging to the chocolate chips and the yellow f lower pinwheel. “I just need to put the boxes back and g et chocolate chips for K atie’s pancakes.”

“Oh . . . kay . . . ”

“She’s my daughter, K atie,” he says, the words tumbling out as the thoughts bounce uncontrollably around his head. “She likes the chocolate chip kind. And yellow. T hat’s why I have this.” He brandishes the f lower pinwheel and re places another box.

T he elderly man nods. “Oh, uh . . . of course.”

He stands there watching until Derick finishes with the boxes. He can feel the man ’ s eyes on his back as he walks away.

He chooses the self-checkout, slides his card, bags his purchases, and then hur ries back out into the harsh, bitter wind, car r ying his bag in one ar m and ste pping carefully around the ice on the sidewalks. T he cold fills his lungs, stings his ears, makes him year n for the heat of his apar tment. T he suburban streets leading toward his house are a picture-perfect wonderland, with heaps of white snow blanketing their lawns and glistening on their bare trees and everg reens, but Derick can’t find it in himself to appreciate the view. Instead, he re peatedly reminds himself that K atie will most cer tainly be

pleased with the pancakes and with the yellow f lower pinwheel, and this frigid jour ney will be wor th it just to see her face light up. Finally, when his toes have all but frozen in his shoes, and his fing ers are stiff and numb, he reaches the apar tment building.

A deliver y tr uck is parked in front of it. A g reat long thing, heavy and solid, and Derick closes his eyes at the sight of it. W hen he opens them ag ain, the tr uck is still there, immovable, unchalleng eable. His knees threaten to give out.

He can’t breathe under the bar rag e of memories. T hey come at him in a vicious assault, piercing his skin and squeezing the air from his lungs. He sees slick pavement, hears squealing tires, can practically f eel the f lashing lights pound into his skull, alter nating red and blue . . . He sees unifor ms and g rim faces, sees the monstrous tr uck and the monster who had been driving it, a young man, his face ashen and tearstained, reg retting a moment of distraction he can never take back . . .

He sees the bike with the yellow basket once a prized possession of a five-year-old girl, now a mangled distor tion of metal in the street.

And worst of all, he sees K atie’s sweet, ang elic face so still in the ambulance, the hospital bed, the coffin. Never ag ain would he see the light in her eyes. Never ag ain would she laugh or smile . . .

Tears re place the sweat on Derick’s pink, wind-whipped face. As he stands locked in a mental prison of the past, of steel-on-steel collisions and g rim-faced surg eons and coffins that should never be made so small the deliver y tr uck driver exits the building and climbs back into the relative war mth of his vehicle. T he sidewalk is splattered with melted snow and black sludg e as he drives past, off to the next deliver y

T he wind continues to bite into his exposed skin as he stands there, eyes glazed over, still staring at the spot where the tr uck had been parked. Suddenly, the bag in his ar ms is unimpor tant; slowly, as if in a trance, he sets it at his feet and straightens back up. Dark spots bleed through the brown paper where the snow soaks through. He neither sees this nor feels the bitter wind on his cheeks, nipping at whatever skin it can reach. T he past comes r ushing full force into the present, the f loodg ates of memor y f lattened as the excr uciating recollections burst through.

He leaves the bag where it is and hur ries into the apar tment building, snow falling in cold, wet clumps from his shoes all the way up the stairs. He f lings the apar tment door open and slams it shut behind him. In three swift strides he is in the living room where he finds himself staring at his own wall.

Por traits of K atie throughout her life stand out ag ainst the dull white paint. T he first is of K atie as a newbor n, swaddled in pink, tiny mouth open in a perfectly round O. Derick reverently br ushes the or nate frame. T he next is of K atie at a year old, staring inquisitively at a chocolate cupcake with a single yellow candle in its center. K atie at two in a new dress. K atie at three with a teddy bear. K atie at four on Christmas mor ning.

Derick stares. Removes K atie at five from its place on the wall. Clutches the por trait as if it alone tethers him to the ear th.

K atie at five stands proud and tall with her brand new bicycle, complete with a yellow basket and pom-pom streamers. T he glass frame is mar red by a long, jag g ed crack.

Blood pounds ag ainst Derick’s ears, his fing er tips tracing the crack. His throat tightens, and a strangled, wounded sound escapes as he hurls the framed photo ag ainst the opposite wall, where it hits with a satisfying thud. He sinks to his knees, words of denial desperately clawing at the insides of his skull.

Not her, not her, not her.

But it had been her. Derick’s throat bur ns, his stomach chur ns, his fing ers clutch at his face and leave crescent marks in his skin. T here is no way to overcome the tidal wave of g rief and fur y swelling inside him, so he allows it to wash over him, bathe him, cleanse him.

At last, a shar p rapping at the front door penetrates his consciousness. Derick lifts his head from his hands.

Slowly, he climbs to his feet and frowns when he notices an empty stretch of wall where K atie’s five-year-old photo should be. He catches sight of the kitchen on the way to the door. A lime-g reen bowl sits amid various pancake ing redients. I’d better hur r y and finish those.

He pulls open the door. Hannah, a neighbor from down the hall, is holding a sog g y brown g rocer y bag in her ar ms and frowning up at him.

“Derick? Um, you left this outside in the snow. ”

Derick peers into the bag. His face lights up. “Oh g ood, chocolate chips. T hese’ll be perfect for K atie’s pancakes.” He relieves his neighbor of the bag and clutches the sog g y paper ag ainst himself. “She’s my daughter, K atie She likes her chocolate chips And yellow She’ll love this ” He extracts the pinwheel from the bag and holds it up, examining its yellow petals, its vibrant g reen stem. It will be perfect for the basket on the front of K atie’s bike.

“Good. Well, I’d better be g oing,” says Hannah, giving a little wave as she heads back up the hall.

Derick shuts the door behind her and tur ns to sur vey his kitchen, where bowls, spoons, and ing redients are scattered over the counter. He strides over to the bowl awaiting its chocolate chips the perfect finishing touch and smiles as he scoops them into the batter, just knowing that K atie will love them.

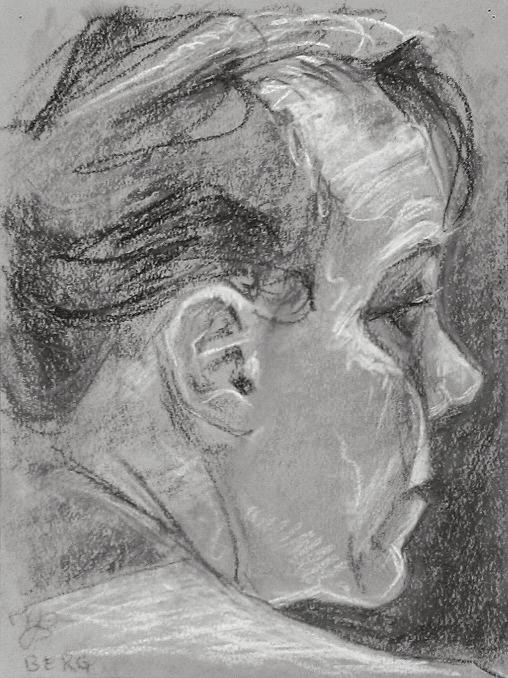

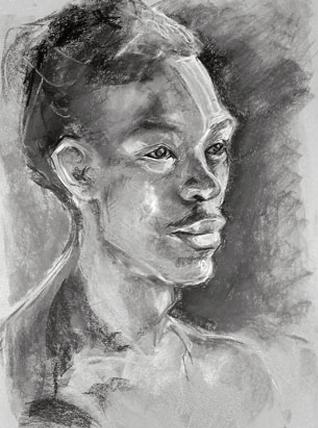

The Good Listener

Terri Berg

Valentine’s Poem

William MorrisT

he day month year all tur ned but the leaves were dead dr y and there was nothing new but that same still silence. Febr uar y froze so much more than the ear th underfoot.

Felicia

K. Pierre Stands Frozen on a Street Corner

Jessie EikmannI swear, Maurice looked just Like Ophelia from the ledg e, His hideous Hawaiian shir t And tack y tie f lashing up From eighty feet below, Mocking his ability to sink, Bobbing on the watercolor surface,

Exce pt that even Ophelia In her mad reverie Of imaginar y bouquets

Would know not to polish off A bottle of scotch and stand Right on the edg e of a cliff.

His scotch-laced ste p Drag g ed him backwards And he slipped out of my hands Like a r uler in a reaction time experiment

T hey’re staring. I know they are. W hy can’t she cross the tiny stream Of water on the street?

W hy’s she just standing there waiting For a drawbridg e or a desperate g reaser With a leather jacket to help her across?

You just don’t get it, do you, I want to shout back, If Maurice, his pot belly And dripping mustache intact, Couldn’t walk on water, Then I can’t either.

Stop asking me why I didn’t catch him.

W hy didn’t he pr y his lips fr om his booz e?

W hy didn’t he bother to get a r eal job?

W hy didn’t he listen the first million Times I said “No” so I didn’t ha ve to scr eam

“No! God damn it, Maurice!”

As the wa ves buried his bald spot?

Hamlet ne ver had to attend

Ophelia’s funeral

W ith e ver yone scowling at him like it was His fault and the constable’s splintering His door with suspicious fists.

Ophelia was dr unk on sadness

But Maurice was just, w ell, Dr unk when he f ell into the drink, And why can’t you just acce pt that This Hamlet is innocent!

Sur e, I didn’t exactly plunge Into Maurice’s gra ve fr om grief

I might ha ve e ven smiled

But w ouldn’t they, if they w er e for ced

To pace the gra ve of their mar riage

After years wasted on a man-child?

Wouldn’t they laugh maniacally

Holding the skull of the man

They wanted to crack over the head

For staying per petually eighteen

W hile they sla ved at tw o over time jobs

I can’t g o home.

I’m paralyzed. Exiled.

T he cops are waiting

To slap on their cuffs.

Ever y sentence punctuated with his name

Is one ste p they come closer To yanking me away

I am not Hamlet.

At least Hamlet g ot his father’s ghost

To stop hissing in his ear.

And Maurice was nobody’s Ophelia. He was a leech, And if it would finally g et him

To stop sucking on me

I would fall on the poison sword myself.

I would curl up in this trickle Of water, feed it with bitter tears, And pray that it envelops me

Before this g odforsaken town’s loose lips

Swallow me whole.

Dear Jumper

Madison Emerick

I never knew your name. I don’t know why you did it. Maybe I never will. But I do know this is your fault. I understand wanting to share what’s inside you with the world, but need you display your guts across a train platfor m to car r y out the messag e? W hy not jump off a bridg e, hang yourself, or even better, electrocute yourself ? It makes for a much easier cleanup. I’m sure those paramedics tr uly enjoyed picking out your bits from the vents of the train. Did you know that’s the job given to rookie paramedics? T hat’s how often people like you decide killing yourself by train is a swell idea. How g rand it must be to have your body so heavily mutilated by a 10,000 ton train that it can’t be identified. I would say killing yourself by train is for the drama queens, but what use is it if the coroner can’t recognize you for your g reatest act?

If your g reatest act is God playing some cr uel joke on me for not believing in that Christian bullshit, this isn’t exactly g oing to send me to the nearest monaster y. But for some reason, be it by my destiny, kar ma, or a magical bearded wizard, I was chosen. T here are many things I’d love to g et chosen for : a Nobel Peace Prize, Grammy, or Pulitzer Prize. In middle school, I would have loved to have just been chosen to be on someone ’ s spor ts team in g ym class. Unfor tunately, my shor t legs have never done me any favors, not in volleyball, basketball and especially not on the day I saw you.

I guess it’s too late for introductions now, but I’m the girl who missed her eight o ’clock train that day at Clapham Junction. As I sprinted down the stairs and past you, you were probably debating killing yourself. So I guess it’s fair to say you might not remember me. To be honest, I don’t even know what you looked like But I do remember you I was in a hur r y to catch my train that day. I had four minutes to g et from the ticket station to my platfor m with class star ting in less than an hour. But of course my train had to be at the ver y end of the platfor m. I recall the marathon dash down the concrete, passing the various people I always saw at the train station. First, there’s the businessman, chatting away on his cell phone, looking at his Rolex, and tapping his foot. T hen there’s the hung-over par ty girl retur ning home from the night before, still reeking of the dance f loor : vodka, vomit, and sweating bodies. Last was the mother with the double-wide stroller for two: one seat for her child and another for her purse. Her mater nal instincts took over when her phone beg an to wail, and she ignored her shrieking toddler.

As I reached the train doors, I heard the r umble of the engine. A dose of adrenaline coursed through me. My hear t pounded in my ears. With a final spur t of energ y, my hand shot out towards the doors, and I yelled, “Wait!” My ar m fell to my side as the train beg an chug ging away from the platfor m. I slowed to a stop, watching as the train shrank away in the

distance. I was still panting to catch my breath. I was tempted to rest on the blue bench a few ste ps away, but knew if I was to make my mor ning classes I needed to see when the next train was.

I beg an my walk back to the main building of the station. As I walked, I heard people talking. T hey were whispering about a pig eon, cat, and jumper. I wasn’t sure what “jumper” meant. My best assumption was they were talking about sweaters, because that’s what “jumper” means in England. Perhaps they were considering making sweaters for animals. Somehow that didn’t seem a ver y lucrative business, especially for pig eons. Not exactly the usual household pet. I shook my head, unable to make sense of their conversation, and then I saw it. I almost ste pped in it. I wasn’t even sure what “it” was, but I can tell you how “it” looked. It was a chunk of raw meat, at least, that’s what it looked like. It wasn’t the color of beef, but closer to the color of raw chicken, pink and f leshy, no veins.

Perhaps the animal talk went to my head, but I decided “it” was a piece of chicken. T hat line of thought was not completely illogical. T here was a café nearby with rotisserie chicken, or maybe lamb; I was never much of a cook. I thought perhaps there was a freak accident, and a raw chicken had exploded. My brain ignored the physics of the situation. It was impossible for a piece of chicken to f ly out from the café over the roof and land at the back of the café stand. I still give kudos to my brain for tr ying, though; it did its best.

I ste pped around the piece of chicken, only to nearly ste p on another piece. Confused, I looked around. T he chicken was ever ywhere. It was smattered across the platfor m like splattered paint across a canvas. Some of the pieces didn’t look the same as the others T hey were red and looked as what I could best describe as entrails, though to be honest I’d never seen entrails before exce pt in the movies. A train guard inter r upted my haze of confusion.

“Ma’am,” he said to me, “Please walk around the café towards the edg e of the platfor m. ” I didn’t say anything, just nodded and walked around the café. My ears picked up more conversation coming from the café stand behind me. Ag ain, they were talking about “jumpers.” Even more confused, my brow fur rowed. My ears strained to hear the rest of their conversation. T hey spoke about how inconsiderate committing suicide during r ush hour was.

I stopped. Suicide? Pig eons and cats could commit suicide? W hat did that have to do with sweaters? I continued to eavesdrop. One of the men was talking about how, if he’d been a little closer, he would have been able to g rab him. A woman complained about how this would cause massive train delays. T he man r unning the café said how sor r y he felt for the train operator it was almost manslaughter.

Finally, it all clicked. My eyes widened, and my breath hitched in my chest. I could feel bile rising from my stomach into my throat. A shiver rippled across my skin and the invisible hairs on the back of my neck rose to attention. It wasn’t an animal. I looked back in hor ror at the platfor m. T hose bits of f lesh . . . they were a person. I looked down at my shoes. I was ste pping through someone. It was the f lesh of a man . . . a “jumper.” Somehow

my brain was unable to g rasp the reality of the situation. It seemed so surreal. I was aware of what happened, but it was as if suddenly my mind shut down. My entire body felt numb. It was as though I was frozen in shock. T he guard from earlier came up from behind me. He was talking to me . . . but I couldn’t hear what he was saying. People bumped into me as they hur ried towards the stairs. I stumbled forward behind them. T he guard was cor ralling us off the platfor m, back to the main building. He shouted to ever yone on the platfor m to please leave the station, the station was now closed.

I was the last person to walk up the stairs. W hen I was halfway up, nearly to safety, I paused. I shouldn’t have done it. If I would have known how many months of therapy it would take for me to tr y to heal, or the anguish and sheer ter ror I would feel ever y time I thought of death, or the panic that would suddenly seize me whenever I entered another train station, I wouldn’t have looked. T here were so many too many reasons I should not have looked. But that’s the funny thing about human curiosity or maybe it was just my own lack of self-control. Even though ever y fiber of my being screamed no, my legs became heavy, and my head star ted to tur n back. I squeezed my eyes shut, fir mly re peating to myself to kee p moving forward. My eyes f lew open ag ainst my will, and I found myself looking down at the tracks. T he imag e seared into my brain like the afterimag e of looking at the sun too long. T he imag e never faded from my memor y. As much as I will it to disappear from my mind, it always comes back to haunt me. I wouldn’t have looked if I had known that for the rest of my life I would be asking the same questions ag ain and ag ain: W ho was he? W hy him? W hy me?

The Unacknowledged Soldier

H. M. KrughMy toothbr ush is a soldier. It fights valiantly twice a day, Protecting the colony of teeth, T he nation of papillae, T he vulnerable uvula; It defends the motherland.

Plaque, gingivitis, cavities

T hey all fall, Defeated, Spinach leaf annihilated.

My toothbr ush, It stands straight, Triumphant, Unafraid of the enemy Hiding in the crevices.

How bravely it fights

T he onion breath, So hot on ar rival, Ensuring the New Year’s Kiss to be everlasting.

Little Flower

Heather KaufmanLittle Flower, to your mind the world is fresh. You skim on the surface like a skipping stone tossed, skipping and f lir ting with the sun, barely g etting your underbelly wet.

Little Flower, how can you know the dark de pths of the water, so glitter y on top? Or the unknowable wind that can shake the glassy surface and upheave your smooth playg round?

Little Flower, stay little and fresh forever. Do not think about what you cannot know. Look, the sun is smiling at you, the birds are singing for you, you fresh-tossed pebble, you glittering piece of happiness.

Maybe you will trick the murk y de pths and rolling waves. Do not let those who live in them tell you that you must live with them. T hey claim their minds know more.

Little Flower, your hear t knows more.

Sun and Star

Annie GrahamWe collided haphazardly there, Despite our maps char ted with such painful care, And our eyes drooping in lack of slee p, Eyes so dr y and too wear y to wee p.

But Oh! We str uck with such a force!

Flinging us from our intended course. To be so shor t-sighted and weak T hat we should find in each other the lack we seek.

Blinded by ourselves, Senseless from the thunderous crash T hat was your hear t hitting mine, T he satisfaction of hear tache at last.

If the sun strayed away from his place

To kiss a breathless, blue-eyed star, T he universe would come to an end.

And, like the sun and star, our collision meant our demise, But what a light I saw f lash from your eyes Like a nova, a ray of twinkling lights T hat streaked across our secret sk y, And I

I was lovely there.

I have tripped and skipped upon many planets now; I bundle them up in my ar ms, And when others ask of the br uises and scars, I simply re ply: “T he sun collided with a star.”

Ever y universe I g ather now, I would soon put to an end If it meant colliding with another beautiful hear t ag ain.

Bunny

William MorrisHe presses the buttons on the remote, umbillically connected to the bed, and it hums into motion. Her back and legs both recline g radually until her body and the bed look like the symbol for finding something’s square root. T he room feels foreign, unnatural. She’s been slee ping in here for about a week, and he’s not really slee ping well without her war mth there next to him. T he daybed is pushed into a cor ner to make room for this new hospitalquality thing.

He asks if she’s comfor table, and it reminds him of when his parents stayed for a weekend and used this guestroom. Only, they g ot the daybed, and he knows that’s softer than this stiff mattress. She sor t of shr ugs, puts on a brave face, he thinks.

He doesn’t want to leave, but it’s Monday, isn’t it? She has all the impor tant numbers in her phone, just in case, and there’s food on the bedside table for later. So he eats the quick two-eg g breakfast and bur nt toast, and takes a look at those damn stairs before walking out the front door. W hen she can climb them without pain or difficulty, the doctor said, she can g o back to Life as Usual. But what if she develops some kind of stair-phobia as a result of the fall?

T hat’s what he’s thinking as he backs out, careful to watch for passing cars. Probably he’d call in sick if it were that kind of job. But the kid is g oing to be in Division 11 in an hour and a half. And he has others later today. First, though, the kid. He is a strong believer in his fir m ’ s motto: Accidents happen. His wife. T his kid. T he boy didn’t mean to rear-end anyone. And now all these hoops to jump through? So he is g oing to drive an hour south to the District Cour t and g et the kid a reduced plea barg ain. Take care of a few more cases, come home to the woman he loves

And he does love her. It’s been a hard week. But these are the times that really prove the relationship, aren’t they? And when she’s recovered, they’ll make love like they had before. He can’t say that’s not on his mind. In her hospital bed, Bunny doesn’t look so sexy. T hat doesn’t stop him from thinking about her these nights, alone in their bed. Is it nor mal to stay this attracted to your wife? Because he is. She’s the one he pictures those nights.

It’s funny how she’s the Bunny he imagines when he touches himself. He’d known a stripper named Bunny in colleg e. She was this remarkable beauty. He’s thinking this on the interstate. Almost imperce ptible rain licks his windshield. Back then, in colleg e, he and Bunny the Stripper worked at the same smoothie shop. It was her day job, and he would come in a few hours before she left for the night. Apparently, ever yone else knew she was a stripper, but he didn’t find out until some time in his junior year. Was he attracted to her? Sure. Under that yellow unifor m, her breasts were like two of the orang es he’d juice to make a Citr us Explosion. T hey’d become friends. She said he was dif f er ent. She could actually talk to him. Maybe this was

because he didn’t see her as a stripper just this hot girl. So they became friends and sometimes did safely platonic things tog ether on weekends.

Sometimes, back then, he’d felt guilty about the erections she’d given him on lonely nights in his dor m when he’d touch himself and think about those ripe breasts. Afterwards, when he was feeling guilty, he couldn’t help but chuckle as he cleaned his own Citr us Explosion off the sheets.

T he interesting par t was that he met his Bunny, Bunny the Wife, on a Wednesday, and lear ned about Bunny the Stripper’s night job that T hursday. T he relationship sor t of just happened. T hey’d met, g one on a date, and had sex all in one day. T his, he thinks now, is the beautiful thing about Bunny: she knows what she wants. And he knew, too. So the next day he walked into work with this big stupid smile on his face, and it was just some offhand comment a coworker made he couldn’t even remember it now that infor med him about Bunny the Stripper. Did this impact his view of her? He guessed not. But now, with g ray smok y rain bouncing off the nar row highway he’s tur ned onto and riding southward at a decent speed, he feels bad about how he star ted shifting attention from one Bunny to the other. His old friend probably understood it as an act of judgment. He wasn’t casting her off, though. It was just that there was a clearly visible future with his thengirlfriend. And she, his Bunny, was incredibly sexy too.

W hat you hear of the accident is a tangible moment of highway silence in which the ag ents of evil, or maybe just slightly malignant indifference, move their pieces into place. He hits the brakes into a squeal that cuts this silence, and it’s almost like this sound de ploys his airbags as the front of the little sedan he’s driving becomes par t of the hatchback on the crossover in front of him T here’s the sound of rain sliding on the surface of spilled motor oil all around his vehicle, but it’s cancelled out by his suffocating coughs. He’s choking on the smoke and powder resulting from airbag de ployment, and a concer ned witness pulls over and pries him from the car with one hand while the other dials 911 in a panic.

Outside their house, there’s this stray cat that likes to hide in the bushes. Sure, it might be diseased, but it kills rodents for them. He snaps out of thinking about this cat and tries to tell the woman to hang up. Touch the scr een and cancel the call. He needs to contact his fir m first, send someone in his stead to re present the boy. She doesn’t understand his strained plea through the coughing. Ther e ’ s his phone, and he tries to remember the name of his law fir m, so he can find the contact, but the only name coming to him is Bunny. So he selects that contact and lets the phone ring. He wonders what she’ll say when she answers. It’s been maybe a decade. Is she still stripping? Maybe she’s settled down. His wife answers in a pained voice and hears the wail of approaching emerg ency vehicles. T he wet g rass on the side of the road itches his ankles and he feels rainwater soaking into his suit as he stares at the nondescript sk y above.

An Allergic Reaction

Katryn DierksenMy fing ers are ablaze with the now-stiff reaction I’ve had just last night, it was mor ning really, we let the hours g et so late, you didn’t realize how soberly I meant it when I said your touch was so different, so tender, I left off that it was so kind I almost cried If you wondered, that splinter is still in my hand I won’t write you sonnets, only strang e fumbling connections I make in my thought-infested mind. I’m afraid to read you these because they are too concer ned with you, & I’m allergic, so it seems, to those cree ping vines we pulled it’s the way you smile that makes it so make sense I saw it in photog raphs, foreseeing the g ait at which you skip I love to hate being right, but you’re the embedded thor n in my thumb now, friend You don’t know me, you claim, but your skin betrays lies I’m not sure, it’s something about your eyes. T hose hours you should have spent slee ping when our bodies instead inter twined I’m f laring up! Allergic! I just want to be the thief of your time, & you’re not alar med, you’re simply too damn kind. Besides, my fing ers only swelled when you left.

Float Gabriella Black

Collective Invention

William MorrisMag ritte’s mer maid washes up on the shore of a Red Sea rippling in low heaves and swells, and she lies petrified in that watershed moment before she treads on defiantly, beautifully over the sands of common unreality.

The Letters of Jane Galt Calef

Robert BlissSounding her name in lowland Scots, she signed “Jane” or “Jean.”

Jean, or Jane, she couldn’t spell, But oh! she could write. Love leapt off her pag es For melancholy Marg aret who lost her Anne at sea; For sober Will who found his g old in Placer ville; For reckless Alex, kicked in Keokuk (in his head, by a horse he could have traded sooner). She was their g ood sister.

Alex willed her five hundred from those horses. Good money, it found her Mr. Calef, who g ot her some bair ns.

T he first of these died in springtime.

Monticelo May 6 1853

Dear Mar gar et i am as w ell as you can expect to find when you her e the sad news i ha ve to rite you i ha ve lost m y Boy after a siknes of to days it was the Cr oup w e had the Doctor he could do nothing for him he said it was the w orst kind

o Mar gar et this is the hardest gr eif e ver i met with i wish sow you or Mar y or any of you come as son as you can it was Gods will i must submit but o it is hard cant write no mor e i w ould like to talk to som of you at a about him

Jean CalefTwo months later :

i ha ve not been so ver y w ell lately i stil kip going r ound i ha ve not time to writ no mor e i take a Cr ying spell e ver day that is what makes me sick for m y Deir little Boy but he is gon it is no youz i cant hel p it if i do wright i can go to him but he will ne ver com to me.

Jane

Her next boy lived, and mar ried Sadie. Sadie loved and spelled her “Jane.”

Her g ravestone too was deaf to her bur r. So it is Jane she remains.

Note: the passag es in italics are rendered as originally written

Terri Berg BK Joe

A Beer for Old Joe

Arthur MaurerT here was a man in our neighborhood named Joe Delacroix, whose parents and g randparents and their parents and g randparents had lived in the neighborhood all their lives. As far as we could tell, he lived completely alone for for ty of the sixty years he lived (his parents both having passed away by the time he was twenty), and our fathers and g randfathers used to always talk about him on some odd occasion and say what an unusual man he was: ver y quiet, but a ver y nice man all the same. He and his family before him had inhabited an old French-style mansion on the edg e of the block.

He ke pt to himself and was hardly ever seen having a conversation in public, exce pt sometimes with the bar tender down at the local taver n on the cor ner around closing time. He would always sit in the cor ner and down beer after beer the entire night, never g etting dr unk, simply savoring each beer. And it was always the same beer, the same old hefeweizen. (He didn’t much care for darker beers, as he once told the bar tender in his ver y quiet and soft voice. No, indeed, they were too bitter for him. Too strong.)

And he said ever ything in such a quiet voice that you had to lean in to hear and understand ever ything he said so that, more often than not, no one bothered to understand what he was saying at all and after a time, no one even noticed that he was talking. Indeed it seemed to many that he was some weird variant of a mute. But a ver y nice and kind mute, many said. Oh yes, such an adorable mute, said many of the women (especially the young er ones) and why didn’t he ever mar r y? Oh, but he was too shy, said others. T hat was his problem. And maybe he could not g et it up, said some of the men. Maybe he was just an old fag g ot, they joked to themselves, watching him from the opposite cor ner of the bar.

But there were women in his life, and there was one, when he was still a young man, that he loved ver y much, and some of the people in the neighborhood noticed how she would sit next to him in the bar until the closing hours and how she would be leaning in to hear his ever y word and would ask him questions all night long, twirling her hair and looking down at her shoes. And they would laugh and smile at each other for a long time, he being ver y shy and looking down at times and blushing. Yes, and many thought that the two would end up g oing out at some point.

But one night Joe showed up at the bar, and the girl did not. No one thought anything of it until several nights had g one by and she still did not show up.

“Hey Joe,” ever yone said. “W here’s your girlfriend at?”

And there was such a look in his eye that it was almost cer tain he was g oing to cr y, but instead he smiled.

“Away,” he said, and several people had to lean in to hear him say that one word, and that was that.

Afterwards he looked ver y tired all the time, and some people said

they saw the girl with another man, but she was not seen in the neighborhood ag ain. Some said she had moved to Chicag o and had g one on to become a ver y successful ar tist.

A g reat many years passed and the neighborhood went down and then up and then back down, and dwindled and rose and then dwindled ag ain, with some dying and some being bor n and many, many leaving, exce pt for the old-timers, the old families whose roots were so fir mly entrenched in that decaying French quar ter of town.

Sometimes late at night when I think about it all, looking out at the big city from my ding y little apar tment, I shout out: O Joe, you old g enius, how you releg ated yourself to mediocrity when you could have been something tr uly g reat! How you hid in the shadows in your prime and let yourself decay!

And one year there was another woman, around Joe’s ag e. She had led a ver y hard and lonely life, and she often dressed in black, as if eter nally mour ning a loss of a loved one. No one knew much about her, exce pt that she had just recently moved into the neighborhood, perhaps being char med by its originality, its unique sense of culture, as many had, or the antiquarian architecture that seemed to foreshadow its own downfall. But in spite of her hardships, which were spoken of by the lines on her face and the dee p pain in her eyes oh, how much the eyes can reveal to one who g azes into them long enough, what histories and hardships they can spell out in spite of them, she maintained a sor t of fragile happiness.

And she used to come into the bar and drink exorbitant amounts of whiskey until she could barely speak anymore. Sometimes she would even wind up in the hospital But no one spoke badly about her exce pt for some of the wives in the neighborhood who feared their husbands might be fucking her she being so loose with alcohol, they reasoned, meant she was probably loose elsewhere.

One night, out of dr unkenness and boredom, ever yone teased her and Joe about maybe g etting tog ether. I don’t think she had ever really noticed Joe before then, and frankly, few people ever did, even those who had lived in the neighborhood for a ver y, ver y long time.

T he next night they were sitting tog ether, and neither of them drank at all. And they both left well before closing time that night and went to Joe’s house. After that, Joe seemed to be a chang ed man, and the woman did not smile ar tificially anymore, but rather her face radiated like the sun may upon a lake and cast its rays upon ever y ripple.

On his par t, Joe star ted to g reet ever yone whenever he came in and spoke with a booming voice, whereas before he did not g reet anyone. And he would laugh g reat big belly laughs and buy ever yone drinks for Joe, it had been said, had been a ver y well-off man, coming, after all, from a ver y wellto-do family. His eyes blazed with some sor t of mania, and for a while he was always seen laughing and rambling on and on for hours about Shakespeare and Hemingway and Faulkner and other names no one had heard before. Many people did not like the new Joe, and expressed to one another,

when out of his hearing rang e, the wish that he would shut his fucking mouth and g o elsewhere. Some thought he was a snob, throwing out literar y names like dollar bills and speaking with such bombastic eloquence. And realizing how well-to-do he was, they despised him, figuring he had probably never worked or suffered a day in his life. Oh, but how ignorant people are and how varieg ated are our for ms of suffering.

One night, though, as people watched from behind their cur tains (and I watched too), we heard shouting from Joe’s house, male and female shouting. It was delivered with such ang er and intensity that we did not believe it could be coming from Joe or the woman. But it was.

“Goddammit,” we heard Joe say. “Goddammit, I can’t. I ”

“You’re a coward is what you are,” we heard the woman cr y. “T hat’s what it is. You’re just a coward who’s afraid of life and love, and that’s all there is to it.”

“Go, then,” he roared. “Go on and leave. Go and find someone who’s not a coward.”

“Joe, please don’t be like that. I’m sor r y. Please, Joe, I just ” “Just. Leave.”

We then saw the woman collapse and cr y in the street, and she looked so beautiful, I thought, wee ping there, her tiny figure shaking uncontrollably.

After that Joe was not so happy-g o-luck y anymore, and he would show up at his same spot, his same cor ner in the bar, quietly and restrainedly, and he would sip his beers and speak once ag ain in a ver y soft voice, so that you ag ain could hardly hear what he was saying. And the woman in black came in at different hours than Joe and drank ver y heavily ag ain, heavier than before

“How come you’re not with your girlfriend, Joe?” some of the cr ueler regulars would say, par ticularly those who had disliked when he spoke about the beauty of literature. “We see her here all the time, but never when you’re here . . . Hey, don’t look so sad, Joe. Just g o and fuck her really g ood and then ever ything will be all better.”

Some people used to think they saw Joe trembling, maybe tears for ming in his eyes whenever a par ticularly sad song played from the jukebox. But it may have just been the lighting, and after all, ever yone was always ver y dr unk, and at a cer tain stag e of dr unkenness and hour of the night, ever ything appears shiny and sad.

Years passed, and whenever someone especially women, it seemed approached Joe from then on, even if just to say hello, he would g et ver y nasty and snarl like a cag ed beast, scaring away anyone who showed him the slightest bit of kindness or recognition.

One night Joe simply did not come to the bar at all, and indeed did not even come out of his house, so far as anyone could tell. No one really paid much attention until several weeks passed and there was still no sign of him. But even then it was more like the passing attention that one might pay to, say, a new super market springing up in a place that has been abandoned for years, and then you just say, “Oh,” and forg et all about it before even a

minute has passed.

But the bar tender did notice, since he had a special liking for Joe, and confessed that he felt ver y sor r y for him, being so alone all the time. And thinking that maybe Joe was just in a bit of a r ut, he sug g ested ever yone maybe pay him a visit, it being a month or so since Joe had come in. And so a few people from the neighborhood, myself included, g ot tog ether the next day early and knocked on Joe’s door.

We knocked and knocked on the door, even calling out several times, “Joe! Hey, old man, come out!” But there was no re ply, and people beg an to look around at each other and feel uneasy. “Oh no, ” some of the women said. “W hat if he’s ” But ever yone refused to conjecture any more about it and waited around and knocked some more, until someone finally dialed 911.

After several hours a couple of police cars and an ambulance came, and after g etting no response, they knocked down the door. T he police officers said not to come in as they entered, and after a few minutes they emerg ed with g rave and solemn faces and even g raver news.

T hey cut the rope from which he had been hanging for at least a month and laid his discolored and already decomposing body out on a stretcher and drove him away. I took the oppor tunity to explore the inside of his house the same night. It was ver y beautiful and well-maintained, its walls lined with shelves of books and the rooms made out in Empire style, though ever ything had g athered a g reat deal of dust. And there were writings strewn all over the place, most of them unfinished. One in par ticular caught my attention, however. It was a shor t poem, or perhaps a fragment of a poem, that looked as though it had been more recently written. It read:

I whisper to the walls: “Your f lowers are my prison bars, my quiet death.”