lt~h t. ,¾ bli nk.mg red jn th e wa , -erin g distan ce. Stream s o f b ackb t

l~a \" buildings ro Ued pas t his , vin dow , an d he had to squin t to

~, ake o ut the park o n the o pp o site side o f the C o r olla.

··So, did yo u- " K. cleared his throa t, " did yo u kn o w J ake Do lan?"

The wiperblades bounced back and forth. Venn wished it were darker as he bit his lip . He just wanted to m ake enough moner to get to Louisiana. K. 's voice had the tremolo of those who ,~alk awa y from funerals, and it reminded Verm of too many thjngs.

The rearview mirror showed a cockeyed view of the backseat, which was covered with a few books and so me fast-food wrappers. He cut over into the right lane. He eased on the brakes, but the car continued to roll forward. Verm pump ed the pedal, but the car continued onward. The brake pads were either shot or below ten percent .

A car ahead of them came to rest at the blinking red ligh t, and Verm broke to the right . Seeing a parked car, h e kept right. The car jumped the curb.

K. braced the dash with his palms. He held his breath.

The car lurched up the sidewalk. Verm cut the wheel back. The car slid on the wet grass. Bushes scratched alo n gside the car. They slid into the dark; the floorboard shook as tree trunks beat against metal. Verm craned his neck and looked at the trees coming toward the passenger's side.

The rear window exploded on the backs of thei r necks. Each bit of glass was like a tambourine, and th ey all pla yed together until falling asleep on the backseat of books.

Verm exhaled and dropped his head against the chair; the r~ofs drapery sagged low, and a new smell fought against that of oil and sweat on his upper lip.

"Is that booze?"

K. hunched over and vomited on his shoes; it splattered back up against the dashboard.

d Verm rolled down his window. The rain blew in from the ark and fell on his arm.

h . K. sat back up, hyperventilating After a couple heav es, e wiped hi " s mouth on his sleeve and said, "Under your seat.

11

"Any cigarettes?"

"I-I quit, but I'm sure there's s h ome ere,, face was pallid; he leaned forward and · K. Said 1-1 • opened the gl q1s ment. ove conipart-

V erm reached under his seat and k pnc ed hi h felt around again and pulled out a bottl f hi s and. Be e o w ske . snapped off. A few pulls were still left at th b Ywi th the neck

1 d h b ttl e ottom· y ang e t e o e and shot down a mouthful H . ' erni barked a dry heave out the window. · e cringed and

"Been awhile since I've had a drink ,, h . h b tl c ' e said tradi K

t e ot e 1or a bent cigarette he'd found ''Y 1 ' ng · . . · ou a right?" V said as he punched 1n the car lighter and wait d £ th erm b . h . . e or e smell of urrung air and the smgle pop that meant th il e co s were hot enough to burn.

K. took a swig off the bottle and handed it b k H 1 ac. e ooked at the puke on his shoes and rolled the window halfwa down. "I think so." y

Verm saw K.'s eyes . They were stretched and wide with shock. He felt he should talk until something was decided.

"I joined before the Gulf-stationed in Texas. Iraq invaded Kuwait, and I knew I'd be in The Shit." Verm said and pulled on the bottle. He held it in his lap like a child, while his fingers bled down the white label. "I got a call a couple days later. It was my uncle Matt-said my old man had died."

K. bent over again, retching a wet splat onto the floorboards, but he nodded the story along.

"I requested a discharge, got it, and went home to my d k d h f eral parlor was father's funeral. It was close cas et, an t e un 1 f h H talked endless Y, quiet. I stayed with my uncle Matt a ter t at. e the . 'd f th ld h d become qwte said since my mother le t, e o man a r quite nd was neve drunk; he'd drank through most of his money a sober enough to find his way home ." . di • ner off but d d the air con uo

V erm reached out an turne d ushed the · k d h h ards on an P 1he left the car running. He flic e t e az 1 d down. · h d already coo e d the cigarette lighter back m because it a I( rolle · · b k n branches. · be rain fell in the headlights against ro e h . yes water; t h 11 made 15 e window all the way down as t e sme . blades were . 1 The wiper ' rain sank through both their s eeves.

12

"The Rousch's daughter'd b slept the night in their barn d . een raped by a man who'd b tl , an Since then h b ot es ofJack Daniels with P ..d ' er rothers filled esttc1 e and mot . the bottles around the barn h or oil. They placed --on aystacks and b so happened my old man wandered throu h ~ross eams. Just way back from the bar." g their property on his

The pop was audible this time V th tle, cleared his throat, and handed it to.K ermh rew ba~k the botd h b ·, w O shook his head b hel t e ottle anyway. Venn lit the cigarette ff h h . ut • . 0 t e ot coil of the lighter and put tt back in the dash.

"Uncle Matt had visited him and said the old man's feet were swoll_en to three times their size, oozing purple and red through sack~ socks. H~ was sitting in his recliner, an unopened beer next to him. He said he sat with the old man for a bit of the evening-no words, though-until he died. I'd only been at Matt's for a handful of days before Desert Storm started.

"I stayed there until I heard about the firefighting crews that were heading to Kuwait. Got basic firefighting training and went with Red Adair-Global Industries, now."

K. handed him the bottle; Verm finished it, the broken glass narrowing the whiskey into his throat. He set the bottle on his lap and began to pick at the label, the cigarette dangled from his mouth.

"Let me have a drag," K. said. Verm blew smoke out the window, pinched it from his lips, and passed it to the passenger seat. K. shifted it from his left hand to his right; the cherry shook between two fingers on his uncalloused hand.

The wind blew in through the open windows and shook the smell loose. Droplets hooked together on the windshield and disappeared with the wiperblades. The rain fell in the stree~ above them; it fell in the open window. Verm could see it clearly 1 ~ rhe light o f th e dash, dripping down his arm and pulling hairs as it went.

metronomic.

13

Escape Above the 'Tree1ines

14

Peering Out

l'iHll Pe1c r s1HI

J ,nnking our 111~1 window at night

I sec men (I, )ing d etestable things,

1\111 d1L'Y can sec mens well, and bett er,

tk c: 1usc ir. is durk out there and light in here

,\nd my window HJuminates their picture of me

( ' upping my hands and pressing my clear face

,\ gn inst it, and the y are stiU, only shapes and shadows

,\nd th e hnrd e r I press to further distinguish

' t 'heir nurlincs from the dark the clearer I am seen

'T<i them, nnd I can never speak of what I saw

Bemuse I can never be sure who it was

l saw

\X ' h<) clearly cou.ld see me

With both hands

Dumbl y cupping my eyes

Peering out into

The darkness.

15

There are smear s in th e wind ow. But th e Li g ht

Hit s th e floor Undisturbed.

Without distortion

Such a feat I cannot mimic!

For I too am smudged and cloudy, But the patterns I mak e on the flo o r I dare not look and see What the light reveals in me.

17

Once it was a m o unt ain to climb . Now, grow n , sh e know s it 's ju st a low ri d ge, and over it a favo ri te pla ce, a perfect pond , artifi ced an d natural, once re servoir fo r a manor hall .

Pines crowd the east, shading roc ks and green grass To the w est, straggling oaks open the pond to evening sun . In limpid water, frog spawn shines. Minnows' scales catch the light Ripples run before the wind The pond shrinks and grows with the rain.

Southward, beyond the weir, Birks Fell rises to seal this scene . This green, hermetic world.

18

Feathered Line-up

Ws en I wa s a kid, back wh en 111 mother still spoke to me, I liked zo o s. W e w o uld alw ays go t< i y lnokashira Zoo because admission was cheap e n o ugh that she could still afford a pack of cigarettes for th e trip h o me O ne summer we went to the zoo no less than sixteen times. Mom had been laid off from her office job, and we had all this fre e time, so we did everything together. I must've been seven or so becau se I had yet to form my intense fear of rhesus monkeys, and I inv ested much of my time at the primate exhibit blowing out my chee ks and making faces at the monkeys, trying to catch their attenti on

But my favorite exhibit was spectacular in concept onl y, and maybe only for kids, or maybe only for kids like me. It was a hatchery of waterfowl eggs lin ed up in rows and under thi s bright, white, sterile light in an unspectacular wooden shed of a building, with a wide plate glass window so people could see the eggs from the outside. On a track above the eggs circled this brown leather boot with frayed laces and a muddy sole. After making my obligatory stops at the elephant, the monkeys, and the cranes, I would spend hours upon hours there. It was a test of patience, not simply for me but for my mother, who would often attempt to drag me away before closing. -\ Th . · a waterfo ,\ e raison d'etre for the exhibit was m seeing h h N b . bl "k ii " but ate · o t ecause ducklings are so adora y awa , beca use that duck's e ntire future was mapped out fr om th ~d ke :1

· · · ~OLU - ta mo m en t i t latd its tiny eyes on that b o ot. R eco grutwn \ f , . . . . :v hng ove r ew seco nd s to se t m, t h e n 1t w as squ eakin g and era, · he h:i tch· It ' If 1. • · • - • 11 ro un d 1 se , c nas mg th e hoot as 1t m ad e 1ts cas ua oo p a.. ck'SL ' r " ') ' . r rr tu gcr ery. ' cc as 1onall y th e re 'd be tw o or t hree aU 1° st 111 t"> _ to tl, t b . . ·ac h o rh et , l a o ot , n ot eve n b o tb e nng to g lance at e,

Boot /\ 01Y Perry

20

Passers b y wo uld tarr y m o m .1 . . . . e nta n \' to Wa tch h , and laug h, and I g uess it was amu si b · h t c du ck li ng, . n g , ut t e fce /1 I I came away w 1th was this overwhelmi ng a wa ys ng se nse of loss \'(/ h those ducklings left a plunging chasm 6 · · ate 1ng etwee n mv bea n d lungs. I felt empty, and vet I couldn't l oo k · a n my 1 · away.

Once, I tned to explain it to m)r mot h _ h . d . d . er, t e o n e time s he acte mtereste instead of rolling her e),es and t · , . uggrng at my a rm to get me to go. She stopped behind me with o ne d . . arm aroun a giant plush tJge~ and the other coming to rest on my sho uld er.

Why was I wastJng so much time with ducks, she asked, wb v didn't I come see the nice squirrels? ··

Because, to me, the ducks weren't simply a demon stration of filial imprinting. It wasn't so much the ridiculousness that th ey saw their mother in that boot. What the exhjbit conve yed for me was the impossibility of self-images, though at seven-eight-nin e I couldn't put it so eloquently. Ducks aren't hatched with an y preconceived notion of what it means to be a duck. The first thing they see is the first and strongest impression the y will ever have about themselves. Even if that thing is as improbable as a leather boot. That's what the exhibit seemed to say.

"They're just stupid ducks." My mother shrugged and turned away. "They don't know what they're doing."

And-"Let's go. They're about to close."

That was the last summer my mother and I spent at the zoo. My mother got a new job working at an art galler~' and spent most of her time screwing the man who owned it. \X'ith m y dad out of town so often on business, I was left to m y own devices for every summer from thereon and opted for pastimes that were more suitable for my budrung adolescent mind. More specifically, petty theft.

It was what all kids from the suburbs rud to pass time. Most weren't any good at it, they'd grab a packet of gum and shove it deep in their pocket before bolting for the door with their face all red and sweaty. They'd get caught, be forced to return w?atever they stole, apologize profusely, and be cured of their mild case of kleptomania. But I had it down to an art form. I used a well-refined mixture of subterfuge, sleight of hand, and goodold-homespun charm.

People are under the impression that thieves have no code

>

21

of ho no r. This simpl y is n' t tru e Even as a chiJd I was hi h morali stic, \.vith a set of rules for sh o plifting that I re f gd ly . use to late o n p ai n o f death. I never stole from a small famil v io. ' · Y-own ed bu sin ess, unless that famil y wa s foreign . I ne ver stole fr om I kn ew o r from a place w here anyone I knew w orked 1 anyo ne uld -1: d b . never stol more than w hat I co ahor to uy at any given tim e fl e . \,est my shoplifting be attnbuted to greed and a lack of funds) . And 1 · 1 · 1 Pl · neve r went mto a store p anrung to stea. anrung would put a d nun ue amount of stress on me, and the shadow of potential fail . ure would lo om over me, make me sick, nervous, uncomfortable.

A n~ I did fail sometimes, but I always managed to talk m way out of 1t. It was around the age of twelve or thirteen that 1 y discovered I had a penchant for the spoken word. I had a knack for crafting conversations in m y favor, to the point where shop owners, once fired up and ready to tan my hide for slipping a box o f strawberry pocky up m y coat sleeve, were actually apologizing for stopping me.

1'1y mother disowned me at sixteen. I had more or less fail ed m y high school entrance exam and had been hanging out with a local bosozoku scamming for panties. I was rarely ever home, and, w hen I was, I rarely spoke and stayed tucked away in my room. One Saturday night I came home to find everything I owned boxed-up and set next to the door. My mother was sitting o n the floor with some man I didn't recognize . My father was now here to be seen

" There are your things," m y mother told me needlessly, w ithout looking at me. "Please take them and go."

I didn't argue, not that I had grounds to do so even if I wa nted to I spent the night in Ueno Park with the homeless, the d ruggie s, and the crazies. The next day I resolved to rid myself of . . . e th e ces sp o ol th a t is Tokyo and bought a bus ticket to 10m som child h ood fri e nds in Osaka.

I didn ' t return until her death. By this time I had alrea Y . th h this was ~ecured my plac e as Uy eda -s a n ' s n ght-hand man, oug f cl e · · cl bun o 1 se\'eral years befo re Uyed a succeeded Saw ada as 1 e oya I . f- . .th rt of men to n o u e-gwn 1. H e o t e re d to se nd m e w-i an esco

1 1did l · al e th oug1 1o n or m,· m oth er. I d e cline d and m ade the tnp on ' and . .. . . , . t- ral home allow hnn to u tth ze a 1 o kyo c o nta ct \vh o ran a un e ses. ' - ket e~ pen. . s haYed th e pnce down t o th e dire c to r s o ut- o t - p o c

d

22

.\fr mother \., as won.h no m o re.

Th e ,xTake was a dr~n- affair made up f thr _ _ · 0 ee mo urner~ : m~-sel~, her o ne _childhood fnend, and the man she had b ought grocenes fr o m tor the pas r m·enn--three \ ears n··e didn' L h - · '' t Sa\· muc to ea c h o ther, too wrapped up in o ur gnef, o r hi ck there of. The picture of her \.ras ou r o f da te and ~-ellmving ar the edges due to he r p ersisten t superstitio us fear th at cameras , and the pictures th at we re taken by them , were ofte n residenc es fo r e\il spirits. Her co rpse didn ' t lo o k much better, th o ugh it didn ' t look th at different from m y memories of her. The onl y difference was no \\· she was dead and s he was n ' t looking at me in the same cross -e\·ed mann er wi th which she regarded insects . But her mouth was f;ozen m a familiar frown , the lines from her nose to the com er of her lip s deepl y etched from rears of wearing that exact expressio n . Her hair was mat wi th sli vers of gray, coarse and fanned o ur around her head in broken, tangled ripples. Someone had attack ed her with a tube of lipstick and some blush. She was dressed in this lurid kimono I had never seen before in m y life. Some caring so ul had slipped some change into her coffin, which I pocketed on m~way out.

He w as standing outside when I stepped our of the temple. I'd like to say it was raining, that the sky was paYed \\,ith gray clouds and the world's colors were suitabl y subdued for mourning. Instead it was a bright, hot day that made the back of my neck prickle \Vith sweat and the sleeves of m y suit stick to m~- arms . I hadn't seen him since before I left home some twe nty yea rs prior, but he was easy to recognize. The way his back and neck stooped from years upon years of unwavering submission to bosses and superiors. His wide lips, wrinkled forehead, and flat nose. Even his suit looked the same.

"Otosan," I said slowly, approaching him. He turned more to me, bowing his head and smiling

''Your mother said you were a fine businessman in Osaka. You look well."

I stopped. After regarding him for a moment, I exten~ed my hand for a westernized greeting not uncommon in the b~srness : 0r1d when dealing \vith foreigners. I could read the con~usion rn s face and watched it change to barely concealed repulsion as he looked down at m y hand. The abrupt end to the pinky finger was

23

1 ng since healed over, but the tip of the ring finger w f o as re shJ bandaged.

There was an awkward silence. My offer for ah andshak W as not met and so I pulled back and bowed slightly th . e ' . . , ough keeping my eyes trained on him.

"It's good to see you again, father."

He returned the bow, lower, almost apologetically. ,,1 heard of your mother and I wanted to do something, som hi ,, H' b k . h d et ng to honor her memory. 1s ac stra1g tene . "I don't know h d ,, exactly what to do, but s e was a goo woman.

I could hardly keep myself from scoffing, turning aw thi · · ul ''Y did ' kn ay to look at no ng m partlc ar. ou n t ow her either th ,, Shi k , en.

"People are a mystery, ge azu. We can't figure out those who won't let us in."

"No, well I guess that would have required you being home once in a while "

My father shook his head sadly, looking away. "Those were hard times. I was wo rking toward seniority in a company that dared give me a chance after I straightened up. I had to give it my all. I had to establish myself. "

"I see." A child rod e b y o n a bicycle, his red cap pulled low over his eyes and his b o ok bag h anging off the end. I had the sudden urge to clothesline him as he passed, catch him in the throat, crush his windpipe, and send him flying. Instead I watched him take a right turn past the temple and roll out of sight.

''You were always such a bright child," he said softly, the subtext saturating every word. What happened? the simple statement seemed to ask. What led such an intelligent child to a life of crime and ritua4 tattoos and folklore, treachery and loyalty?

"I would like to spend some time with you, if you're going to be in town for any length of time."

"I've got to be in Osaka on Friday for business." I closed · h · fi h · · ket "But l my eyes, t1g terung my mgers over t e coms m my poc · have somewhere we can go, if you've got eight hundred ye n to spare."

H

• f Shin ' iuk u e nodded. So we caught the next tram ro m f statio n to Kichij o ji. Again the silence between us bloomed out t l b . . h f small ta lk co ntra , u t neither of us was gifted with t e art O • · ' · t

· b 11y hoc\v was acute y aware o f t he position o f every hm o n 1

•

y

24

E , e ~ - mO\ e m e nt seemed fo rc ed h es ·r l , , 1 am. wa s sure f could se n se ho,v un easy I \\,·as T he · · my athcr . · co rn ers o f my · · 6 clo ud and d arke n . I was o nce again e . . VJ sion ega n to xpen ennng th e famili sation of falling in o n m!rself, wha t Uyed a-san h d ar sen" bl k h 1 " t-c h · a come to calJ the ac , o e e iect, w en every m o ment am h d . b ' p s t e es peratJo n to get away, ut you re trapped ph ysicalhr or mo 11 7 I b d d . , · 1 ra ) · egan to shut own, an 1t w asn t until we had put a good te · . ' n nunutes wo rth of walking between oursel ves and th e train station th t d d a we es cen ed down the steps to the gaping mouth of the park I w • as ove rcom e with a sweeping nostalgia that started at the back of my brain and worked its way forward .

"I know this really good Vietnamese place," my father spoke up. ''When you were a child you never wanted Japanese food, do you remember that? We sometimes joked that maybe we had accidentally switched babies with some gaijin ."

I had to bite my tongue to keep from commenting, but it was not just a small part of me that believed he would have loved to find out that I was actually some foreigner's child, that his real child was out there in some foreign land. A successful salary man with a wife and a family and a wonderfully ordinary penchant for Japanese food.

"I don't want to eat. I want to go to the zoo."

He paused. "The zoo? What's there?"

I didn't answer.

Inokashira Zoo doesn't have the same profound effect on adults that it does on children. Maybe the added height affords a different angle on the cramped exhibits and vacant cages with prerecorded calls that give the impression of wildlife. I gather that it is a bit of a running joke among park goers who go for a concentrated shot of sympathy for the aging and graying animals that call the park home. There are a lot of noteworthy sights at the park, but the zoo is not one of them.

We entered the southern subsection of the zoo, a part wholly unattached from the main attractions with the elephant, monkeys, and squirrels. This was the area that housed the swans, the <lucks, th e gee se, and other aquaticall y inclined creatures. \Xie go t there an ho ur be for e d o se and th e park was all but empty. My f~ th er pajd our admi ss io n with o ut lo oking at m e, but his expressio n spoke bemu seme nt.

25

"Mom and I used to come here," 1 spoke up With being prompted. " E xcept you wouldn't know about th ~ut · · b I'd h · at. .1 oer was this one exhibit. . . ut rat er Just show you." e

We rounded the swan pen and headed for th e rarnsb kl enclosure that housed the hatchery. Only the buildin ac e . g Wasn't th The space where 1t once stood was now barren an op ere. d . ' en patcb f dirt just off the path marke only by a pile of wooden 1 ° a fading sign, years old and illegible. Not far beyond thp anks and . at was a murky brown pond that exuded this smell of mossy bird shi

"F k " t. UC ...

I stopped short. My father stopped alongside me 1 out onto the manmade pond with his brow furrowed and ~oking corners of his mouth turned down in thought. t e

"I don't see any ducks."

Of course he was referring to the pond, where the matted grass and stench gave off the impression of waterfowl unsee H n. e had never been to the exhibit; he had no idea that that exhibit was my entire reason for going there in the first place. To tiliat zoo to my mother's funeral, to Tokyo, it had been my goal all along t~ revisit this spot. Not because I wanted to reminisce, but because that exhibit stood out as the single most profound event of my childhood, and, by re-establishing its existence, I don't know, maybe I thought it would make me feel better about the fact that I had never real1y known my mother. Just like those ducks never got a chance to know theirs.

''We used to come here, her and I, when you were at work." I said slowly, taking a step forward and turning in a full circle, gazing around as if to determine where the hatchery was, where they'd moved it, if they'd moved it. -;>"

''Your mother and you? Are you sure.

"All h . " t e time. . fl b fore 1 · t me br1e Y e

My father pursed his lips, g ancmg up a . and . kl und his eyes , turning away. He looked so old, the wrm es aro fath er. tl at was not my , the fine gray hair had to belong to a man 1 ' d alien to . . hi f e seeme so And while the signs of age that s ace wor · . re hi111 at . . . h I ouldn't p1ctu .

me, I couldn't picture h1m young e1t er. c 11 d·d \'PLI a . . 1of birds, t .·

"Shige , yo ur m oth e r was d ea. thly afratc know that?"

26

•·1 didn't." 1 fn.)wn~d, wondering what he was driving at The w:\y he spoh-, cmphas1z1.ng practically every syllable, he was trving cu say something without actually saying it .

· "She was. She told me once, long before we married, that ~he had been caught in a thunderstorm on her way home from ~choPI. t\ flock of ~~cse r:ew overhead and the lead goose passed thnnigb a streak ot hghtmng and died. He fell to the ground, feet :1w,\)' from your mother, and the other geese followed. They just flew straight down into the street, it was rainjng geese and your 1110111 was in the middle of it. Screaming. She said the sound was hm-rible, the wet smack when they landed."

" ... That doesn't make any sense."

''Well, 1 don't know how true it was. She was on several medications at the time, and known for her embellishments. But she acted hke it was. She hated going to parks and would never come with me to the sakura festival. And this zoo ... " he shook his head. ' 'She never would have been able to come here. She would have had a fit."

I turned to him. "So what are you saying?" I demanded, my voice rough with irritation and the tiniest hint of apprehension. "That I never came here with my mother? That I just made that up.)"

"I'm not sure what it means," he admitted, not yielding to my anger though keeping his gaze in the general direction of the pond. "I will say I'd be surprised if your mother took you anywhere. She was going through a difficult time, you know All those doctors, they couldn't find anything wrong with her leg. And I always had to work. But you always got to stay with Chiasa-chan when your mother was going through a low period. I guess there were more downs than ups at that time, so you probably spent more time with Chiasa than you ever did out with your mother, vou remember."

, Only I djdn't. The name didn't recall any images from the back of my mind, but at the same time, I felt the expectation of recognition numbing my brain. The feeling paralyzed my lips and tongue .

"\Y./ -who?"

' ' Kitagawa Chiasa. Don't you remember? She Lived next duor with her aunt and would come over to watch you . 1 gave her

27

e tiincs Sl 1 , .l 1ur rnuLhn cu uld I , ou t su m . , ,, VL· tl1 k~ you ,, t mon ey to ta for a few h o ur s I Use to herself d t C) rhink back t() a ll thos e tnp s We ,,... I 10 • , , I w e •ll t· t ' '1 see · _ f n w t11l)th er s tarted to \\ ' c: ,1kc n :t n :i 1 1 ll rr1-. 0 se im ages O · l ) ur the zoo. 111 , "a, s blurt\' . ln those memun es, ~he , ' th were ,u\v . w ., , or maybe ey h ,.., tev e r wa s around me- th e dL1C~k.s ,1 ndarY to w " . . le always seco 1 · h t 1 h ad n eYe r qucsuon e d the.: validin , uf 1 . l th e e ep a n . J r iu -; e sqwrre s, 1 esence, b eca us e 1t h ad a lwa ys seemed li k . ries or ier pr t.: '.\ me . mo ' h w·d<lv b ega n to d estru c t the longer I thouirht given. But t ey 9 -' L • ,-, Dn it. The woman had short hair, but my m ot h e r ha<l always l hal r tl1at grew dow n h er back. She was scared of sc i,,s had ong t:- • ' - ors, .6 d f cuttino- h erself. The woman tn m y m e m o n es had tern 1e o o pierced ears and wore j~wel ry, neither of which my m o d es t mother would ever consider domg. And the woman smok~d, not a lot, but whenever she got tens e and nervous sh e' d shake out a cigarette and flick the lighter flame on with these long, sharp, d ee p-red talons.

Father absolutely refused to let my mother kee p her nail s long for fear she'd scratch herself raw.

"I see," I said again, squinting agai nst the glare as the clouds broke overhead enough to allow a thin strea m of concentrated sunlight to slip through. "So l neve r spent any time with my mother, at all."

" Never that I saw," my father admitted regr etfull y. "And you never said an ything that suggeste d otherwise."

Somehow the knowledge that I h ad long mistaken the women in m y memories for m y mother failed to jar me with the same slap to the stomach that disco ve ring my favorite exhibit had been torn down. Nly mother was no real loss, she was gone whetber I rememb~red her or not. But that e~hibit, those ducklings I l d h d . l y father. ~, 1 a a such a burning desire to share that witi m Now 1 would neve r get to share th a t with him, and I felt anger. Some of th at was dir ected at the zoo for nullifying perhaps th e onh- e ·l ·b · · . . · t- ·t was : x. ,i it Wl th any tntn gue whatsoever. But mo st O 1 directed at . f. . . L h I was a kid . _ ' my ath er, for n ever taking an interest w en_ hefl it

, tor neve r .,.· · . · to htrn w U . pv111g m e an o pporturuty to show it trao!l;e st1 eXls ted F 1 . . _. l some s ' ,, . · · o r ·eavtn c.r m e to make memori es wit 1 • , five \\ oman wl , . b ll rwe11t) 10 ~e nan1 c 1 wouldn't eve n b e abl e to reca

years later. . . _

· I went silent for a long un1e, prompung my tath e r to eak after minutes in silence. "\Xlhat are we looking for h e re,

e? I could help yo u find it if I knew what it was."

g "Nothing, it was nothing," I n1umbled as I turned away, trying to keep my walk steady as I headed back toward the entrance. At that moment I just needed to get away from that lace and from my father. Unsure of whether or not he was following me, my pace picked up, until I was almost running for a dump of bushes. Bile rushed up my throat and I hunched over and retched into some foliage. I felt dizzy, off-kilter. My head buzzed and my face flushed hot as my vision blurred and darkened. I was having an episode right there in the goddamned park, the strongest I'd experienced since Hiroshi's death.

I had never felt so isolated. I tasted the sour vomit on my tongue and felt the tree bark rub the pads of my fingers dry as I clutched the tree, heaving, struggling not to pass out. But it was all experienced in third person. I was locked within myself, blind to the world. Defenseless. Although I felt eyes on me, I had no way of knowing whether or not there was anyone around.

It was no longer about the boot, or the stupid ducklings that followed it blindly, thinking it was their mother. The only lasting sentiment that exhibit had ever left me with was a profound sense of disappointment. Every time a duckling hatched, a part of me expected this duck to be different, this duck to be self-aware enough to take one look at that molded mess of string, leather, and rubber and realize that boot had nothing on him. But it never happened; every duckling, without fail, would accept that fucking boot.

It was the fact that I had been given the chance to hate my mother, but never the opportunity to know her. That she was dea_d and nobody cared, least of all her son. I had a father who ea s1.ly and emotionlessly shattered the fa~ade I had built up around rn v childho 1 d A f: I h, · < • at 1er who had never been there but somehow t at hadn't t' I . f . ' . f l · a <en away rom his matter-of-fact authority. And none o t1athadhoth d ·1 . co I ·Id _ · _ere me untJ now, now that there was nothmg I uc uaboutit.

I felt- a lnn d t • · l · - Jd and tu . · ' cntat1ve y touch th e back ot my shou er, ' rn1ng to lo I· I ·I . .. . · 0 ' Jae<, I had the bnd delusion that 1t was

~t

29

H. shi hovering over me But it wasn't. My father took iro . a step b k regarding me nervously, one hand fidgeting with hi . ac , s necktie

"Are you all nght, Shige? Should I call someone over;)'' ·

"I'm fine." I said dully, getting to m y ~eet. I wiped m~ mouth with the back of my hand before glanc1ng over at him. "I have to get back to Osaka."

He nodded. "If ... you are ever in Tokyo on business " ) and you have time ...

"I'll look you up." I lied. My father smiled. I almost felt bad, giving him false hope. Or maybe he was just being polite and in actuality could not wait to be rid of me, his criminal screw-up of a son. I'll never know, I never saw him again. And yeah, looking back, it doesn't fill me with joy to know that the last words I ever said to my father were a lie, but it doesn't necessarily fill me with remorse either. I can't say I care much one way or another.

When I got back to Osaka, Uyeda asked me how the funeral was. Fine, I said, very beautiful. He asked me if I needed time away, which was as close as he could get to asking if I was all right without actually asking. I said no, that the Inoue-gumi was my family, the ones that would always take care of me. To take time away from that would be to force me to dwell on the loss of a mother who had never mothered in even the loosest sense of the word. I wanted to keep busy with the gang's affairs. It was, after all, what I was good at.

Uyeda just smiled and nodded. When his lips turned up, the corners of his eyes deepened into wrinkles that stretched past his hairline. A little bit he reminded me of my father's sad smile, but only a little.

The exhibit was gone, but for a long time after I couldn't shak e the · · klin blindlY - image In my head of those newborn due gs, · and fa1thfuUy following that boot.

30

rhe last time we talked

1,J lctl f lcrgct we were: ca ug ht in t h e s un ;uid r;:i n for a trnjn which you reac h e d fir st and 111 ~1d e th em hold for me.

J sturnblcd in a nd wish e d yo u wouldn't search my face this time, red from the h e at and aJJ thos e p eop le who stared at us and li ste ned to our sinall talk.

J I

English 2720 and the Romantic Poets

Luella M. Isbell

I sit in dassa wax y, tri -fo ld sack of tightl y bound darkJ y secret kernels.

Unexpectedly, th e re fl ective musings of sweetly debated ghosts bo mbard me, causing an almost molecular change.

l pop, pop, pop,

as powe rful verses pummel me, sending me soa rin g, softl y tumbLng, ex pandmg into existence.

Eng]j sb 2720 and the Romantic Poets

33

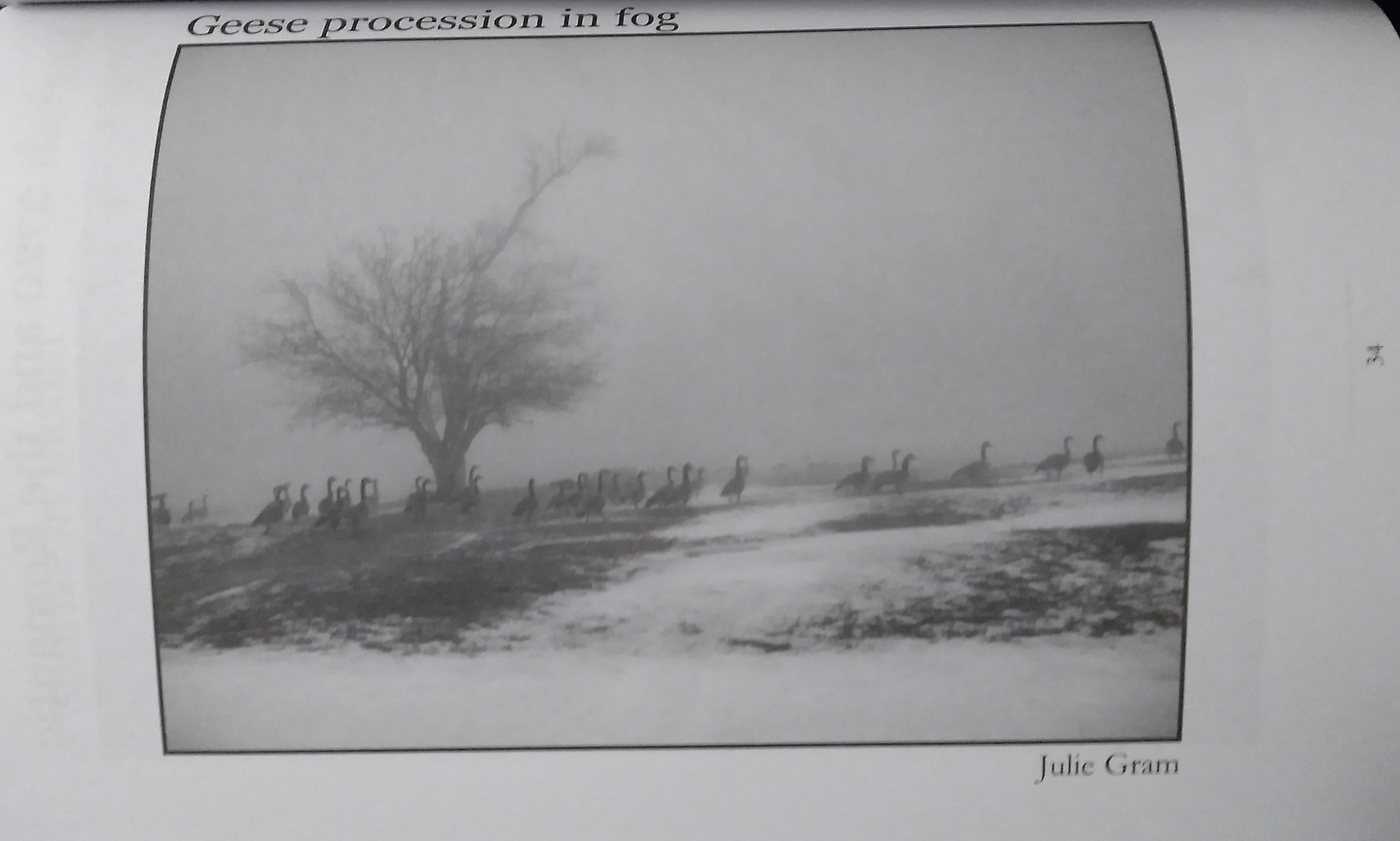

Geese procession_ in fog

Les Corneilles

Robert j\1. Bliss

In th e P ari s mus e um s

Yo ungsters e nter fr eel y

To fl y over stone fl oors

And flutt er up marbl e stairs.

Paying nothing, dressed in Internati o nal style, Black o n black , Th ey flock like crows

Culling treasures:

Clever, curious, cauti o u s, Companionable, Cacophonous .

rrrres tl1ere will be

beep

Nat haniel 11 unton

Two ca rdin als fi g ht T erritory m a tter s m os t Not o nc oming car

111111----

Morn: A Memoir of MY Early Years

ll M. Isbell 1ue a

ll M. Isbell 1ue a

Iwas born the year that yo u turned 37, your only girl. "A rose between two thorns," you said of me. I always wondered how my brothers felt about those prickly words. I don't remember you before you had your first big attack of multiple sclerosis. At 14 months I couldn't have understood. If I had not been sent to live with kindly distant relatives when you had to stay in the hospital, we might have giggled like sisters as we learned skills together. Instead, I stared wonder-eyed around Aunt Marjorie's home in Maryland, while you were seeing double in a Virginia hospital. I babbled to Uncle Dunc with easy innocence, while you were straining to free once-familiar words from your tangled tongue. My chubby little legs grew sure of the ground beneath them, while the mutiny of your once-experienced limbs increased As I developed, you languished. And that could have been the end of our story, but I was always a kitten to yo ur tiger. You fought like a wild thing and clawed your way back to health and home and then they brought me back home, too.

I_do remember playing trolls under the tree roots that buckled th e sidewalk and spread like gnarly arms along the right of way. You even d · · d ma e ttny clothes for my trolls, sewing on teeny seqmns an pearls and one tiny snap to close the back. Your tortured hands , numb de!' · and unresponsive must have struggled to sew such icate dev · ' otton on such tiny frocks. I think I loved those ug ly trolls m ore than all d . I my sweet-faced baby dolls. I know yo u playe wit 1 me Under th l d · ' re e maple trees, because you told m e late r , but on t th::rn?er any specific day. When I was older, you let me _s k:nc sidewalks with their jagged buttes and valleys, krn)wtng nil

pt

39

. 1 would fall. You knew that smearing bloody sl-: _ the while th at . l £ . . l'uil

d alk s was a simp e pnce to pay o r gauung the t 0 11 rough s1 ew erocity o f a tigress.

d troll dolls with their bright, wild hair spikin~ up lik I love my ' 1:::, e

n Cand)r· their cute-ugly faces and swollen bellies mold neon cotto , .ed in the hardest plastic. I waved them upside down watching their hair slowly wave . That was when I learned that I liked to tell stories. I would sit on my bed and wave the troll upside down, mesmerized by the Wting hair, speaking fantasies aloud to no audience but myself. Later, I used a scrap of pink terrycloth shaped like a triangle. It, too, moved in a way that I liked. Daddy used to call it my little pink rag and I was unsure if he understood how magic it was. I made more and more sophisticated storytellers as I grew. I always needed something to occupy my eyes and hands while my mind skipped blithely on from one imaginative story to another.

Tommy, the younger thorn, born when I was five and you were 41 was a built-in audience for my tales. He would sit rapt as I spun yarn after yarn, often holding a storyteller made from pink ya rn that I had carefully crocheted into little hanging spider arms. I not only loved to write poems and stories, but I enjoyed quiet tasks like reading and listening to my records. I could daydream for h 1 · ours, ymg tummy down on the cool wood floor of my tiny roo li · m, sterung to the yellow vinyl records full of nursery rhymes a nd folk songs we had bought at a rummage sale. We had no preschools sum k nd ve t ' mer camps, arate lessons or sports teams a ; our days wer full S . . . e · nuggling Ling-my faithful Siamese catmothenng my d ll d " my b O s, an roughhousing with "the thornsrothers-provid d . d d Mv ld e me with all the enrichment I nee e · ; wor spun i b h n ng tly colored simplicity.

There w ·..,k ere trees t li . · big pil' peo ni e 0 c mb, bikes to ride and in the spring, 1 _ s to sniff I ' h a go rious fl ow · rem ember being darkl y curious why sue II er Would h b the snia bl ack ant h ar o r such p e rsistent nuisanc es as ' s t at swa r d h I p eoni es and ants c me t e stems a nd tickled my s .;:rn. 1 are LOte r 11 ft 1C ver Ink ed in m y mind. I love d the sme 0

40

d k earthy dirt-floored clubhouse , with its swin ai ar ' . ' ' . . c,ng rope: ladder h t I couldn t maneuver but David co uld. T here w b l t a . . as are y !>pace: lie in the upper story, but he w o uld glo ry 1n hi s s up · k to en 0 r s ilJs d Stay up there for as long as I hung o n th e ladd e r c.l h . an wi ned to join. I am sure he soon bored of th e sp o rt, but sta tu s mu ~t bt carefully preserved i~ a family and he knew that I th o ught he was very big. We three kids all loved the Paul ey I sland rop e hammock It hung between ~o ste~l poles and we wo uld tak e turn s lying in it on our backs, s~ll as frightened prey, whil e the o th ers flipp ed it over and over until we were wrapped up tight as a spid er' s lunch. You never approved of this form of entertainment, and we became your prey if you caught us at it.

Meanwhile, you had vanquished your disease to a dark co rn er o f your life. You spent your time organizing the first MS chapter in Virginia and still found time to make us pancakes in the shape s o f animals, taking requests as we sat patiently at the breakfast tabl e calling out impossible shapes for you to form with lump y batt er on a sizzling griddle. You taught us manners and you taught us how to read. You made our beds and you made our peanut butter sandwiches to eat in the dirt with the ants and the spiders. I guess you did nap more than other moms, and I knew you were older than many of the other mommies, but I never felt an ything fr o m you but unconditional love in those early days. In spite o f yo ur physical trials, your weary nerves and numb limbs, you managed to stitch our days together with the sequins of your time and the pearls of your devotion. You may not have appreciated all of o ur roughhouse play, but you spent what energy you had, during th ose early days of our lives, weaving a cocoon of love around us that was tighter and more secure than any Paule y Island spid er' s lunch .

4·1

Television Said

Robert A nth ony Jones

Eat more

Diet

Drink m o re

Diet

Spend yo ur last dollar

Image is very important

You need an obsession

Lose weight

Tune-in

Tune-out

Sit down

Don't go out

Tune-in for more programming

For more programming

More programming

Programming programs

To program you

Diet

Buy your way to happiness

Kids suck

Marriage is prison

Food is therapy

Materials define your identity

Diet

Eat

Lose weight

Don't think

Drink and be entertained

Be vain

Blo nd e hair and blue eyes are beauty

D o n't que sti o n

Eat

Di et

Your body nee d s work

Es cape rea li ty

Eat more Di et

42

Tun e-in

'j'unc -out

Sit down

Don't go out

Tune-in for more pr~gramming

For more programmtng

More programming

Programming programs

To program you

New is good

Old is bad

Eat more

Diet

Shop 'til you drop (literally)

Black men are violent

Live in fear

Spend, spend, spend

You can have a good time with alcohol

Image is very important

Spend your last dollar

Products are the answer to your prayers

Tune-in

Tune-out

Sit down

Don't go out

Tune-in for more programming

Fo r more programming

More programming

Programming programs

To pn >gram you

Rau new s is:

Th e news for you

Bau news is:

'rh c.: new s for you

43

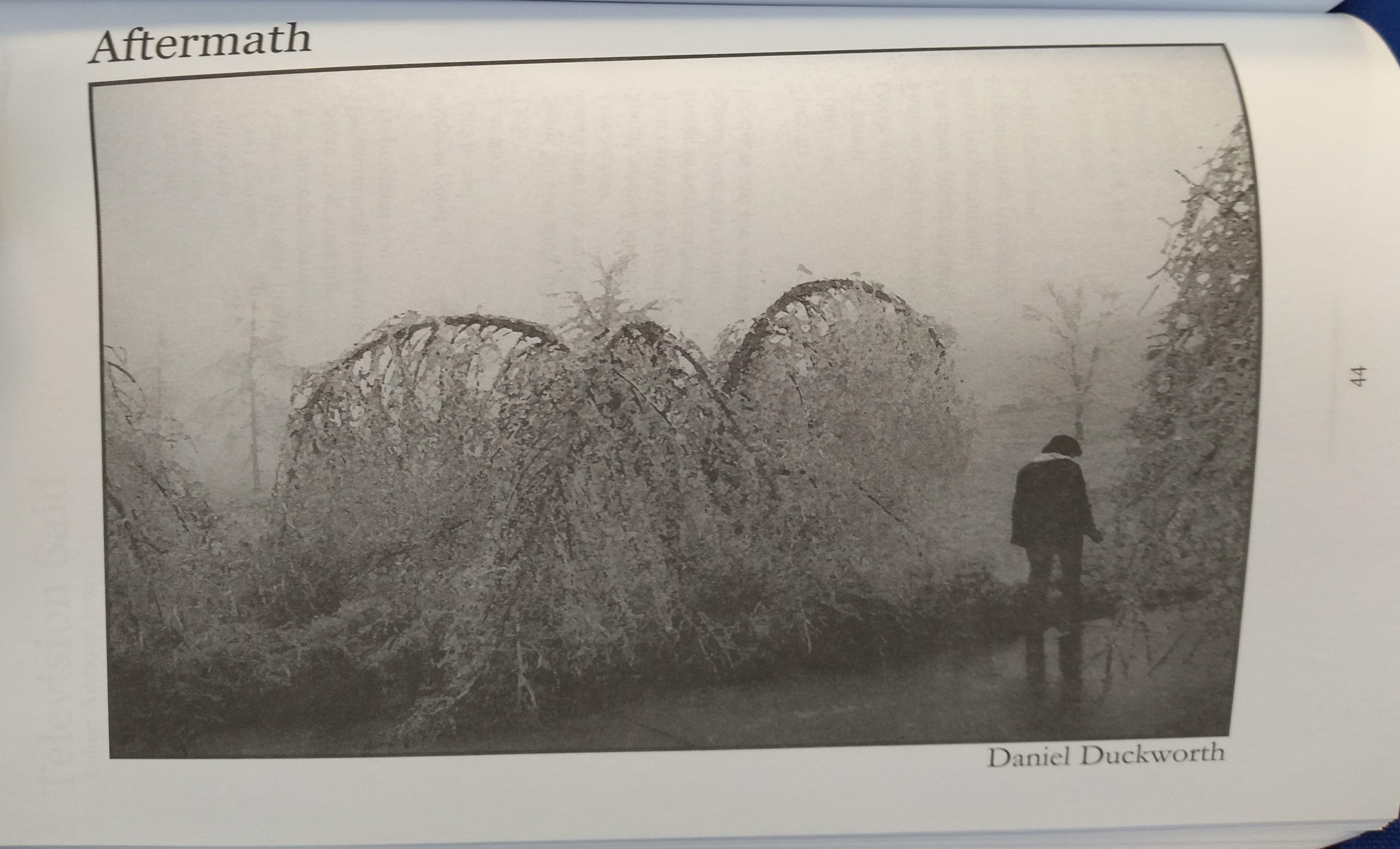

Aftermath

somos H ermanas

oevry Becker

It's easy to say what might have h . appened in another poss1 ble world, where the same people and things exist in different locations. We could talk about it all day, but we don't have that. It doesn't exjst. It isn't even useful. All that we can do or be is what we have or are capable of.

All that we have is this world, this minute. I'm not sad about it, and I'm glad that you're my hermana.

I think about why I call you my sister We're not blood related; we're not even women. I've never had a brother, and I will not start now.

Before I flew to Maryland to greet you face to face, I told people you were the best friend I'd never met. Now we have. This Internet has opened up new experiences in both our lives, and that was evident in our sororal embrace when the luggage and I stepped out of the airport.

You are my hermana, and f don't re m e mb e r when or why

ihat happened, but i t wa sn't a mi s takc..:.

l t wa sn' t an acc id e nt.

45

46 ) ker l ).u11d I tt t

Flowers

Jabbering about "Jabberwo

'~as bril!ig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; All mims y were the borogoves, .And the mome raths outgrabe.

'Beware the Jabberwock, m y son! The jaw s that bite, the claws that catch! Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun The frumious Bandersnatch!"

'

He took his vorpal sword in hand: Long time the manxome foe he soughtSo rested he by the Tumtum tree, .And stood awhile in thought.

And , as in uffish thought he stood, The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame, Came whiffling through the tulgey wood , And burbled as it camel

One two! One two! And through and through The vorpal blade went snicker-snack! He left it dead and with its head ' H e we nt galumphing b ack.

" And has t th o u slain th e j abbe rw oc k?

Co m e to m y arm s, my bea mi sh boy!

0 fr abj o us d ay! Call oo h! Ca ll ay !"

He ch o rtl ed in hi s joy.

·e1 Care\· C Y Dafll ·

k ,,

J. 7

,,..[\ ms brillig, and the slith~- tcwes Di d gyre and gimble in the wabe : b.

All mim sy \Yere the borogm·es , .And the mome raths outgrabe.

- "Jabb erw ocky" (Carroll 13 9)

Witn-, ingenio us, sa rc asti c, and o ft en metaph oric al ks Pos~e d to Intern et ne\,·sgroups are co nsi dered snark ( remar . . . . small "s" and hopefull y no t Booium 1 ) Like a bt erary co nc eit , the more complex, obscure, co~pacted,_ ~nd ~eleva nt snark _is, th e more debating points the writer dev ising it sco res Lewis Carro ll is known to have said \vo rd s to the effect o f " L do n' t know" whenever asked about th e mea ning of hi s "Jabb erwoc ky" (Ca rroll and Gardner 17-18). In sayi ng variations of this, he empl oys th e Victorian equivalent o f snark to gain debating poi nt s on his critics, to intentionally mi sdir ect us from his int end ed meaning, and thereby to illustrate hi s point. Poet Carroll surely kn ows what he intends to convey by "Jabberwock y"; his co mments imply th at th e meaning of the po em is mostly unknown until assigned by a reader and that the mea ning assigned b y any particular reader , even him, will change over time. The poem its elf also resembles snark. ''Jabberwocky" uses portentous, incantat ory gibb erish and a profound-soundin g narrati ve to metaph o rically sa tirize self-congratulatory literary critics who assign meaning to it.

Carroll provides many clu es to hi s intenti on that we read "Jabberwocky" as a satire. Alice con sid ers th e po em in Chapter 1 of Through th e Looking Glass. Her criticism pr ov id es what has to be almost everyone's first impression of it, but h er simple analys is suggests mine. The use and placem ent o f ev ocative nonsense words and stanzas, along with the poem's narrati ve, contribute to th ~ satire. Alice's actions, before and after she analyzes the po~m, mirror 2 and reinforce the satirical ideas provided b y the narr~uve .

. Alice rea d s "Jabberwock y" and then gives an imme~iat~ anal ys is H fi · · ·u 11inaung

. · er irst critical response help s, but the m ost 1 ui ' thin g sh · · , e says 1s tn p arenth es is:

"I d c. ·sh ed it,

.t seems rather pretnr " she sai d w h e n sh e ha 1111 ~,

"I . ' L; ' l d dn t

. )U t It s rather h a rd to und ersta nd!" (J. o u see s i e 1 r like t f- . - -Id ' t 111 ake 1 0 con ess, eve n to h erse lf , that sh e cou n out at all) "S l • . l , d \vith . _ { · ' - · o m e 10w it see n,s to fill my 7ca · vc r, id eas- l 1 , . , . 1 Ho,ve o n Y el em t kn ow exa ctl y w h a t th e) arc.

48

somebotjy kill ed somethina: That 's I <') c ea r at , any ratl ,, - (11<; Ali ce stands in for all critic s w ith h e r anal • S ; f h ys 1s. hen excellent form o t e p o em ; th e wo rd s are Otl ~ thl p retty a d h even though many are n o n se n se Sh e d oes n 't n r yt hmi c, h · d · want to ad · to herself, that s e Just o e s n o t und e rsta n d •t mi t, c.: vt:n f Ali ' l . i at all Tht fi h sentences o ce s ana ys1s co uld appl y to th fi · . in,t t re;t: C . . e trst rtad m,, f almost any poem. ntlcs nev er want to admit th h . ,s 0 d k d . ' at t ey don' t understan a wor , an its a sh o rt st ep fr o m thi d 1 b . . AJj b . s ern a to ass1,, - ing an ar 1trary mearung . ce o th p rovid es and · •~ . . h Th satmzes a cri tical review with er comments. e non se n se in th e P . • • oe m so un ds fu ll of ommously sigruficant mearung; yo u can alm os t pictu · h . . re witc t ~ around a cauldron mtorung the non sense _sta:11za (lin es 1-4, 25 28). Carroll couples a ballad rhyme scheme with internal alliterati on and the narrative seems right out of a bard's heroic tale. This ai'I gives Alice the feeling or intuition that "Jabberwo cky' ' simply mu st be full of meaning to match its form and sound o f pro fundi ty, bu t it merely fills her head up with unknown ideas. It is ind eed cl ear that somebody killed something in it, but Alice's unexpresse d questions, which require answers, are "Who exactl y is the somebocfy?" and ''What is the nature of the som ething that is lcilled ?"

Examinations of the use of nonsense word s, th e con struction of the poem, and the narrative answer Alice' s questions. Peter Heath notes:

The most curious thing about this poem is that, th ~ugh everybody agrees that it is great nonse~se, nobod y ts prepared to leave it that way. Carroll himself, Humpty Dumpty and a host of succeeding comment~tors, ha: e ' . d' eanmgs for its labored diligently to mvent or 1scover m unfamiliar terms. (139)

Al h f h urious habits of t ough discounting the smokescreen ° t e c . . H ty slith . • il d I d by cnt1c ump Y toves 3 and the like arb1trar y ec are ll' and D f: 11 · Carro s trap Utnpty, I myself can't help but also a mto 1 th e nonse nse provide analy sis of his nonsens e (195). Car ro ~ uses rath er th an ~ rd "Jabberwocky" as the poem's titl e , for 105t a~~e, more cl ea rl y he Jabb erwock" for a r ea so n. Carro ll's ch ~~en dt1 ":o nk y." T he sugges t I "' I ber an d s a po rtmanteau o f th e wore s Ja J · • shaky, an central · · ro ng awt Y, · as iss ue o f th e po e m th e n b e co m e s w ' thi s way, acts ' · eeble b bb . f h poe m 1n. h a a lin g talk. Th e v e ry titl e o t e .• 'bbc rwock 1s t c sarcast· · • . ·i.1 · c the Ja le cnt1c1 s m o f t he p oem. .J ccau s ·

49

tu re slain in th e n arrati v e , th e title suggests that th crea e po . al O the thing slain The slayer o f the beast the n 1 . ern itself 1s s ogi call sen ts a li te rary criti c-a h unter for meaning. Y repre.

The p o em b egins and ends wjth the same Sta

E thi . nza one f aJmos t comple te non sense . ven s c o nstruc tio n subtl _'di 0 · l . th · · ) gs at criti cs analyzing the po em , unp ymg ey will li kewise begin . h ~ili and end up Wlt n onsen se .

The narrative of the poem reinforc es thi s satire of .. f "J bb k ,, . cn a- ci sm . The narrator o a erwo c y 1s not the person who kills the Jabberwock; he provides cautions, an account of the h and congratulations. Carroll suggests that th e narrator is either:, father of, or a mentor to, the person who actuall y slays the Jabberwock. His narrator uses the phrase "my son" and lis ts possible pitfalls of the hunt: '" Beware the J abberwock, m y son ! / Tue jaws that bite, the claws that catch! / Beware the J ub jub bird, and shun / The frumious Bandersnatch!"' (lines 5-9). Because of the way this is written, the caution could apply equally well to an y critic reading it. There's a lot of peril in this verse for a criti c, and the narrator identifies its source-the nonsense words-b y warning about the Jabberwock, Jubjub bird, and frumious Bandersnatch. Carroll's nonsense words indeed emanate danger, because there's the nigh-irresistible temptation to assign them arbitrary meaning.

The narrator continues skewering critics b y providing his second-hand, hearsay discussion of another critic's hunt for meaning. In the third and fourth stanzas, the word "thought" is repeated. The hunter/ critic can't find the J abbe1wock, so he stands "awhile in thought" (line 12). After what seems a very short inter:'al, the Jabberwock comes upon the now-pensive hunter : "And as in uffish thought he stood, / The Jabberwock, with eye s of fl~me, I Came whiffling through the tulgey wood, / And burbled as tt c I" (Ii 1 k' yes ame. nes 3-16). The narrator highlights the Jabberwoc s e to strengthen the notion that it represents the poem. The eyes (tra- d..

ittonal port~ls to the soul) flame showing that like a poem,_ ~e J abbe_rwoc k 1s a creation of pure imagination with a fi.ery_sptrtt. D es pite th e narrator's caution regarding the many potential haz~t<ls, th e end of the hunt is quite anti-climactic. The hunter juS t hack s o~f th e Jabberwock's head "s nicker-snack," and rides 0 ~ 0 me with it (li 18 ' · t a little th h . ne ) . The hunt's rather easy end after JUS . k oug t 1s a s ti · 1 Th y thtn b . a nca m etaphor aimed at literary critics. e a out a po em t b. . hat they thi k · or a 1t, then pull out a pen and explam w n 1s everyth · b . ·ghtter than mg a out It. The critic's pen here 1s way mt the any normal d . . d an cut swor -lt 1s like a vorp al sword an so c

b

50

h ad clean off anything. The hunter's sword gets its e al . awesome ower from a magic nonsens~ word, Just as a critic's en P wer from the nonsense corrung out of it. The end fp h gets its po .f h . . . o t e narra. e sounds as 1 t e narrator 1s v1canously sharing 111 · th . uv . e triumph of the hunter, and 1t comes off as self-congratulatory in "O frabjous day! Ca~ooh, Callay! / He chortled in his joy" (lines 23 _ 24). After analy~u~g a poem m an es say or re:iew, critics usually reiterate how brilliantly the y have proved their point and b ldl congratulate themselv es for a job well done, so another i·abo t y. , f . h a critics is the ~arrator s use o tnump ant nonsense expletives to end his narrative.

Alice discovers a book containing the mirror image of "Jabberwocky" lying on a table n ear the White King in Through the Looking Glass. She can't read the book at all, but after she has "puzzled over this for some time," however, "at last a bright thought struck her" (138). Alice realizes that it's a looking-glass book, and the poem ''J abberwocky" must therefore be held up to a mirror to be understood When she does, she must also see herself in the mirror with the poem. In the reflected image, she would dwarf the book. This metaphorically suggests that any criticism of a poem is a folly similar to holding it and the critic up to a mirror together. Critics just see w h at they want to see in a poem; the y project themselves and thei r experien ce into any unknown, which is folly. After Alice gives her quick and easy analysis of the poem, she giddily floats down the stairs in the air in triumph, her feet never touching the ground. All these images of Alice par~llel those of the critic/hunter in the poem, and Carroll reinforces his mockery of critics by them 4•

51

Carroll, Lewis and Martin Gardner. Th e A11notated Snark. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1962.

Heath, Peter and Lewis Carroll. Th e Philosoph er's Alice: Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through th e Look ing Class. New York: St. Martin's, 1974.

1 The semi-obscure reference to a Charles Dodgson a.k.a. Lewis Carroll poem about hunting a Snark (a beast on the same island as the Jabberwock), the fact that the uncountable noun "snark" is a portmanteau of snide and remark, the sideways reference to the perils of the unknown with the word Boojum (a particularly deadly, hidden type of Snark), and even my misdirection of the reader to this really long footnote to demonstrate and explain my point, all contextually help make the parenthetical an example of snark.

2 I hope the reader will forgive my inability to resist using both this verb and this form in my essay.

3 Dumpty alleges (without citing a shred of peer-reviewed evidence) that slithy toves nest under sundials, live on an all-cheese diet, and gyre around on the surrounding grass plot.

4 "Callooh, Callay!" (23).

\Xiorks

Cited

52

The Fly

A :Measure of Consumption Pica.

\,t'lli \lkn

J he didn't believ e "he s:uu :-- · h

, 1 rcr0us consumption w en In dn1 g 1 ~ than expected- Thin~s got roug 1et , 11 ·dcr in her mouth, ,ll ·1

.:: -1Jowed down less easJ y''tl

Turned up in the throat Wl 1 Too much worm, too much Skin on the bone.

She thinks being pregnant Must mean to fulfill all desire And so bends to fill her bones . .A bit of foam, palest green, At her lip will fall bounce back Up as if to reclaim itself Inside her, but becomes instead, Earth and soap.

Her hands too thick

With grit and bark, her tongue heavier Still, holding down the ground's Soft creatures, cracking their bones To dust she can breath, swallow.

Taste is of no consequence.

\Xbat neighbors may see

In the lit take of her meal '

What the y may believe about Sanity and possession, animals

And belonging, does not occur to her.

What could be conspicuous, she knows Is sacred for life . OnJy the tilted paclcling

Un<l cr hn ':io lcs , the w e tnes s

She fe,-1 ... 1·h I . I - '- roug1 eve ry s uite( Mom ent of ea ting-

. .

This is the measure rh at call s Her rhrough the night To the great wing of feeding, over And over-That beginning Hunger and anatomy.

55

Jack Russell

])cvry Rec ker

)' o u remind me of a Jack Russell terrier, with aU the extra e nergy you ha ve all the time, wit h aU th e extra atte nti on yo u requ ire all the time.

-

/

• puppies

57

J(ate Blankineyer

Thegrg.du.'ll evolution of \Yestem

Euro pe's old churches-fro m romanesque to gothic to re naissance to baroque to rococo-strikes me as bearing some resemblance to a young child's first sand castle It starts out clean and so lid md mass ive on its fiat surroundings as it overlooks its enemies . But then the lad notices other kids building them too . So he begins to deco rate, dripping soaked sand here and there, adding on ntrreiS and statues and flags and guardhouses, finally ev,en embellishing with ice cream sticks and cand y wrappers and gumdrops. - -- - -

Across the street from the Midget R estauran t nea.r Ha.rYard Square , some students living in a grimy o ld re nted house have elevated Cambridge p op art to new hei g hts . On th ei r la"vn , resting on a twelve-foot slab, the re's a perfectly proportio n ed nude, about twice the size of life, lyi ng sideways with her breasts exposed to the street. Her shoulders and bell y and thighs are soft and delicate and lovely-simple, clean curves, with all the classic grace of a . sculpture in the Pitti Palace. The slab has carved on it calligraph.le letters "Venus de Mass. Avenue." The whole thing is done in ice . . al A din . vex verttc t a er 10 Falmouth the counter stools have con . surf Th th distortt 0115 aces. ey are kept highly polished, so that e

L orts Peter f uss

58

fl cted by the brass are distinct and clear. Wh . re e . en a Waitress or Swmer walks by, the whole diner comes to life s . . cu . . . , warming with that person. This is what Lollis XIV must have wanted from his Ball of Mirrors.

But the reflecting surfaces are rounded horizontall ll . . y as we_ each stool nurrors at its own angle, as if it were from 1-t . . . sown pomt Of view. This 1s different from the Hall of Mirrors mor d 1 , e or er y, more continuous, more able to register images of life. One wonders: did Leibniz see something like this when he had his philosophical vision of the monads?

The "old fool" Don Quixote tilted at windmills, deeming them to be evil monsters he had to vanquish. But suppose that this champion of the oppressed had already had an intuitive grasp of what Marx, centuries later, was to immortalize in an epigram: "The windmill made the feudal lord." Quixote, a profound reactionary and peerless romantic, might then conceivably have understood that the next step, the commodification of all facets of life, would mean the end of fidelity, valor, selflessness and love. - --- -

During the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) the Germans ~ad dl . · This experience en essly everything to lose and nothing to gam. rn h c ) d gree of emouon- ay ave triggered the unusual (even 1or m en e al b till tim es find s among num ness and inarticulateness one s some th fford to feel any- ern. Under conditions like these, who can a . . ,. thin , . . , l puls1ve sav tng, , g, n<::v<:: r mind express 1t? There s a so com .. ,d Ct r ' . us hoard c t s ,11 man s arc am o ng t h e w orld s more egregto · inrw- )qu · . . I· th ere on e ca n . .-. . irrele rs. In d a rk place s a nd b e low gro un c · I .ft I licn1, in e th I . 1· I . IYHI bee n l e )es iegc d G e rm a ns stas hin g w h a t itt c ' howeve . I th e ti in e r u seless it mu st h ave scc m cc at 1 , , s ur - An<l ..- .., , S co uld no t l ,l\ l . · th e n t h e re ' s a lc o h o l. fh c (J c t m a n . . 1 1 lc i,rcss 1on , vived h ' . . I I ff su 1c 1c a c t 15 protracte d ord ea l have wat c cc 0 ,

' l

59 J

without booze. But there was probably also a kind of Darwinian 1 • t of those who became alcoholics as being too dys- se ectmg ou functional, a danger to their fellows. Somewhere along the line the Germans developed or adopted a good idea in this connection: give the kids beer or Schnapps in small doses at a very young age to demystify those and enure them.

Adam and Eve were right to cover themselves with fig leaves. But they should have done it much sooner, and over a different portion of their anatomy. There's nothing inherently shameful about genitalia; and far from certain that public nudity, especially once people got accustomed to it, would necessarily retard human progress. But to have taken so long to begin asking questions, and even then only at the repeated urgings of a "lower animal"-now that was shameful. The fig leaves should have been in place from the beginning, squarely in the middle of their foreheads.

-in memoriam Ulrich Sonnenmann

e11Vr1ter

The Fourth Reich

Bobb y Meile

Did you know that when he died , Hitler' s Ghost was sent back in time?

Caught up in a temporal tic, he was displaced in the ] urassic.

Giant insects 'velociraptors: by his spirit their bodies captured

What horror ' what oppression! Nothing deserves Hitler Possession!

For years on after he flexed his might; then fate did him in with a meteorite.

62

SouI

Vegetarian Love Song

D evry Becker

D evry Becker

You know how I say that I want yo u to b e my chickpea?

\Veil, it's not true, no, it's not true I really want you to be my garbanzo bean.

-----64 Q

Tinder

Daniel Diecker

Wailing like a falling satellite, he strode quietly into a crowded market.

Over pointed barbs he wore innocence, there wasn't a second glance.

A button pushed and he explodes, his legs sheared below the knee from shrapnel remain standing bare like matchstick trees in Tunguska.

65

Wilted Rose 2

11111

66

Gothic in Terms of Catherine's Growth

j\,{egan Leedle

Asthe stonn rages and various noises and wind strike my ears at intervals, I find myself tossing about my bed, unable to sleep, unable to "have neither response nor comfort," counting down the "tedious hours" until I can again read from Jane Austen's Northanger Abbry and discover the evil secrets that threaten Catherine's happiness (Awsten 162). Except that I, unlike Catherine, do not fear that General Tilney is a murderous, "unkind husband" (Austen 170). Instead, I fear that General Tilney's evil is of a much worse nature, something more realistic but all the more terrifying.

Scholars have often viewed Jane Austen's Northanger Abbry as a Gothic parody that expands upon eighteenth-century views of the novel as dangerous in the hands of over-imaginative women. Many readers view Catherine Morland as a dim-witted girl who foolishly trusts to fantastical illusions and argue that Austen presents reality as sufficiently interesting in comparison to illusion. Scholars like John K. Mathison argue that Catherine's growth is contingent upon "her rejection of the Gothic" and "an advance to truer view of society" (147). These scholars see Catherine as an Jnexper1· d · • · th G thi d escape an

: · ence girl eager to mdulge m e o can

Otdinary · b ndoning all

. · existence, a girl who can only grow upon a a . . aspects of h G , . . " h eral ordinar1. n · . . t e oth1c and happily acceptmg t e gen .e$s (J f Lfe" (Glock 38) . .

~rL ·1. • • , d C therine's 1ilu~- ·nt e many cntics are quick to con emn a · , .,Jo ns ·

· f Gothic Dov· grounded iQ the Gothk, I believe it is her reading 0 · ~s that ·it . . . · c ·1within men. . · · a uws her to p e rceive the capacity ior evi

. fhe

67

. M th on I would argue that Catherine should not Unlike a is ' . . cornt the Gothic. While she must certainl y stop 1 -um pletely reJeC . Ping 6 nclusions and must re1ect fantasies that "Mrs T ·i to terrt 1C co ' . . t ney li d shut up for causes unknown," Catherin e should hol i · ' yet ve , , . . c on to her skepticism about mans mtent10ns (Austen 177).

Catherine's illusions prepare her for experiences in reality, experiences that reveal the actual evils of avarice and ambition that others do not even begin to perceive. Thus, the Gothic serves as a valuable tool that helps Catherine grow to understand the evil that exists in reality. Just as Catherine grows to recognize th.is evil, so do Austen's readers come to realize the immoral nature of an eighteenth-century English society where imperialism has increasingly caused men to be more interested in money than honor.

In order to understand where Catherine's fascination with the Gothic originates and to appreciate her eventual growth, it is important to examine Austen's characterization of Catherine. Scholar Sarah Emsley believes that Catherine represents "the almost blank state of human nature-not yet educated in the ways of the world, either good or bad" (49). Austen herself portrays Catherine as a girl who "never could learn or understand anything before she was taught" (16). According to these explanations, Catherine must be viewed as a moldable piece of clay, one who is greatly influenced by the words she reads; readers should not confuse these portrayals as proof that Catherine is simply dimwitted. As a girl who was raised around relatively few people in the countryside, Catherine derives her knowledge of good and evil chiefly from reading. Austen emphasizes that Catherine has already learned from various writers prior to her admittance into Bath society and has taken the following lesson from Shakespeare to _ heart: "The poor beetle, which we tread upon, / In corporal 5utfc rance feels a pang as great/ As when a giant di es" (qtd in Austen 17). Influenced by such literary works, Cath e rin e trea ts all PC(p ] . . 11 d f t :\' <."11th .

> e equa Y a n naturally accepts friends both o grc~ ' · · · such ac; th , T. l d h · rl1 L · . · · c ·1 neys, an of more meager m e an s , s ue · Tho Th · f th eir rp es. 15 acceptance of aJl w1thout any co n ce rn or . . ()( posse ss ion - · . J , bch·t\ 'tt1t s or in comes si-and s in s tark contrast to 1 ,c ·

68

any in Bath, who, as scholar Roy Porter 1 . rn " exp ams, still ) ·udices that there always would or ind d h mamtain pre , ee s ould b oor" (15). , e rich and p Not only does Catherine differ from th . . 1 h d . . ose chiefly con erned with wea t an ambition, but she also .c re1ects the pro · that stems from society's adherence to rules meant t difr p~iety . h h o ierenttate the classes. Etg teent -century readers would h 6 . ' . . . ave een shocked by Catherme s natural mteract1on with Henry at the th eatre and her blatant rejection of propriety. Yet, as scholar Sarah Em 1 . . , " . s ey pomts out, Catherme s principles are instinctively good" (52). Catherine is "quite wild" to apologize to Henry and replies to Henry's formal greeting "not with such calmness" as propriety would call for (Austen 89). However, the "feelings rather natural than heroic" that possess Catherine come across as more sincere than any apology deemed appropriate in a social conduct manual (Austen 89). Catherine, who may possess "nothing of the conscious correctness and sententiousness to be found in the ideal heroine of a didactic novel," most certainly favors acting naturally over obeying society's instructions concerning propriety (McK.illop 40). It is not that Catherine is dimwitted or without knowledge about such propriety-after all, Catherine's mother has surely instructed her in the ways of Sir Charles Grandison, a moralistic novel by Samuel Ri h fi d "very enter- chardson that both Catherine and her mot er m taining" (Austen 40). Rather, Catherine instinctively realizes that . , 1 d people to do what society s sense of propriety does not always ea . . i h d h suspicion of those

8 ng t. This instinct will eventually lea to er wh Th ·t is important to rec0 are too wrapped up in propriety. us, i all ogn· C c b havmg natur Y

ize atherine's instinctual preference ior e een rath h d the contrast betw er t an artificially in order to understan . large. Catb · h t ry society at en ne' s values and those of eighteent -cen u ed

1 and unconcern

. Whereas Catherine is extremely natura ed with With w l h . hjghly concern eat or propriety, General Tilney JS "all praise appearin N h ger Abbey, th ·g Wealthy. In their tour of ort · an · 1 ,, while ' ' the at had rn . h Li' d b the Genera , CGst1· · uc meamng, was supp e Y Id be nothing iness o l , fitting - up cou . to'' C re ega nce of any room s 1 -

1 beHev1ng athe · T'l wrong Y

nne (Austen 172). General I ney,

69

Catherine to be the benefacto r of the Allen family' s wealth as Well h " 7 n famil y' s as sumed wealth, wo mes that he " can tem as er o-pt [her] neither by amusement no r sp lendour" (Austen 132) .

Unfortunately, General T ilney' s effo rts to flaunt his wealth come across as inexplicably u~atural ~o Cathe~e. Had ?eneral Tilney stopped worrying about unpressmg Cathenne and sunply allowed her to freely explore the abbey, Catherine migh t never have imag- ined the General's dispos ition as unnatural or evil. Scholar Edward Neill notes how Catherine discovers General Tilney "is anxiously competitive and complacent b y turns about his own property, status and style of life" (20) . Catherine is unaccustomed to General Tilney's ambition and feel s "relieved by the separation" of General Tilney because she can resume her natural self with Eleanor (Austen 169). When General Tilney leaves, Catherine is free to imaginatively explore the abbey without the General's forc - ing "her to tell him in words, that she had never seen any gardens at all equal to" his (Austen 168). Catherine feels uncomfortable around General Tilney, yet cannot understand w hy she should feel this way given his benevolence as a " gentleman-like man" (Austen 124). Therefore, she is left to interpret her feelings of discomfort as a sign that some evil must lurk within General Tilney. Unfortunately, her inexperience causes her to relate this evil to what she has read about in Gothic novels. Catherine intuits a sense of evil within General Tilney as he continues to emphasize wealth and property, yet she mistakes the source of this perceived evil because she herself possesses no feelings of avarice or ambition. In trying to come to terms with her uneasiness toward General Tilney, Catherine jumps to the con- clusion that he must be a murderous, ungrateful husband. Due to her lack of experience, she associates General Tilney with charac- ters of which "she had often read" (Austen 171). Because the only evil Catherine has learned of yet occurs in Gothic novels, she assumes General Tilney must fit the part of a Gothic villain. Scholar Edward Neill believes that "in Catherine's very 'dangerous . . ll'ilie prevalence of imagination' she holds what Blake would ca d f ~ro~ en ° a golden string"' (18). I would agree, and go as

70

that Catherine's imagination is a helpful tool. Critics h ave often rejected the dangerous and immature nature of Catherine' s imagination as exhibited through the scenes at Northanger Abbey. According to John K. Mathison, Austen "sets o ut to show th at the kinds of events that normally take place in the li fe of a yo ung girl of Catherine's position may be sufficient both for the maturing o f the heroine, and for the subject of a novel" (143) . Ye t, I vi ew Austen's opinion of the Gothic in a different light While Catherine definitely learns from reality, the value of her experiences through fiction should not be underappreci ated. Gothic novels help Catherine by first opening her eyes to the mere potential for evil within men, allowing her to imagine an immorali ty within General Tilney, although it is the wrong form of evil . General Tilney still turns out to be monstrous, "though what is monstrous about him is only social greed and banality," not murderous desires and thankfulness for his wife's death (Levine 335). Those moments when Catherine gratefully leav es the General's presence, moments she feels must stem from his harboring the familiar evil of Gothic villains, are the very instances that reveal General Tilney's actual immoral sense of greed. General Tilney's greed proves most convincing when he discov ers that Catherine comes from no substantial wealth, upon which time he sends her out from the abbey without explanation in a terribly monstrous manner. Catherine is forced to face a "journey of seventy miles ... alone, unattended," a departure "of the greatest consequence; to comfort, appearance, propriety, to [Catherine's] family, to the world" (Austen 211). General Tilney's treatment of Catherine comes across as extremely severe, especially since Catherine must travel alone and risk both her virtue and reputation. After all, "in polite society a lady's chastity before marriage" was "thought crucial by gentlemen" (Porter 25). Thus, General Tilney does not simply attempt to end Catherine's relationship with Henry, but also endangers her from receiving the attentions of any other respectable gentlemen. As Catherine later discovers, the "General had had nothing to accuse her of, nothing to lay to her charge, but her being the involuntary, unconscious obje~t of a deception which his pride could not pardon . • • She was guilty only of being less rich than he had supposed her to be" (AuS ten

71

228).

General Tilney simply ~annot acc~pt that he h~s acted so 1 tl y albeit with an a.1r of bragging and showmg off benevo en , . . ' d o-irl of less financial means. His actions reveal the upper towar ab- .class society's fear of the rising, untitled rmddle class. Ultimately, his extreme avarice and ambition cause him to act "neither honourably nor feelingly-neither as a gentleman nor as a parent" (Austen 218). When General Tilney feels the endangerment of hi s status and wealth by Catherine's social class, he sets aside all honor and instead behaves monstrously.

Jane Austen presents General Tilney's greed as "a domestic but more serious monstrosity than that of, say, Lewis's The Monk, because it is a social commonplace" (Levine 336). The General's greed mirrors that of a society who increasingly worries about money rather than honor. Examples of society's progressively warped priorities exist throughout Bath, yet Catherine does not originally recognize them because of her own lack of ambition and avarice. Conversations between Catherine and various friends reveal the nature of these characters' chief concerns . For instance, Catherine and Henry speak "on such matters as naturally arose from the objects around them" without any consideration of wealth (Austen 25). That is, until Mrs. Allen arrives and Henry must shift his comments upon the equality of the sexes to the more materialistic and less significant matter of the cost of muslin. Such an interjection as Mrs. Allen's occurs often in Bath society, where moral issues frequently take a backseat to matters of wealth and appearance. For example, when Catherine attempts to discuss author Samuel Richardson's moralistic novel Sir Charles Grandison with her friend, Isabella admits her opinion that the novel "had not been readable" (Austen 40). Instead of continuing this m ore important discussion, though, Isabella begins pressing Catherine to decide "what to wear" and consider what "men take no tice of'' (Austen 41 ). Mrs. Allen and Isabella, characters who are less natural and more willing to prescribe to social expecta_tions · . · d ·ires m term s of propriety, can be understood in terms of their es to stand out in Bath society. The mate rialistic values o f th esc h women w ere common in a society wh e re "differentiation was I e

72

key" and "was endlessly echoed by accent and idiom, dress, address, and addresses" (Porter 16).

Like Isabella, John Thorpe also becomes too absorbed by his ambition to be concerned with any moral issues. For instance, John prefers to brag about the price of his carriage upon first meeting Catherine and later questions her about Mr. Allen's wealth as a means of assessing her value. Catherine shrugs off John's comment, "Mr. Allen is as rich as a Jew," and shifts to address the moral issue of partaking in alcohol, a subject that would be taken more seriously by a man like Henry Tilney than a man like John (Austen 62). Still, John's preoccupation with Catherine's wealth stems from his own ambitious desires. After all, if he can propose a marriage between himself and Catherine, he too might enjoy the Allen's great wealth, which he only assumes Catherine must inherit. As scholar John K. Mathison explains, John Thorpe's actions stem from "evil motives" that Catherine "could never have suspected" given her lack of experiences in such a materialistic society (144). John Thorpe's misrepresentation of Catherine's wealth is a means of appealing to another greedy man, General Tilney. Nothing would please John more than "to dine with" a man like General Tilney, who "gives famous dinners" and is "as rich as a Jew" (Austen 91). Even if it means he must falsely present Catherine as "the finest girl in Bath" in order to gain the approval of such a man as Tilney, John will do it, regardless of who he might eventually hurt because of his avarice and ambition (Austen 91). Such actions as John Thorpe's parallel those of Gothic villains who . destroy young women's hopes of love for their own pe~sonal ~ams. Likewise these actions reveal the evil behind society's mcreasmg . ' d · f materialistic values. emphasis upon wealth an possession o . , E v en though Catherine mistakes General T1lney s ev1~ as

h

his actual avaric e ongmating fr o m murde rous desires rat er a

rality th at oth ers or ambiti o n she still p e rceives a sense

h

"m

. ,, . , .

nster o f ava ri ce fail to rec ognize. A.N. Kaul claim s t at t e . . " b uel and ru thl ess as any Catherine discove rs tu rn s o ut to e as er · (I. . '\48) If

,ev tn c monster she had im agined, and not h a

Y N t A

ey inclu mg · · et, many characters within ortlJange r . ' ' ·

73 -

.

th n

f · mo

O im

.

h

o

re m o te"

· so . d' th ose su ch

bb