14 minute read

A Stitch Around Her Mouth Fiction by Etaf Rum

The Stitch Around Her Mouth

FIc t Ion By eta F ruM

Advertisement

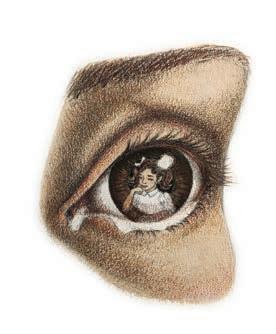

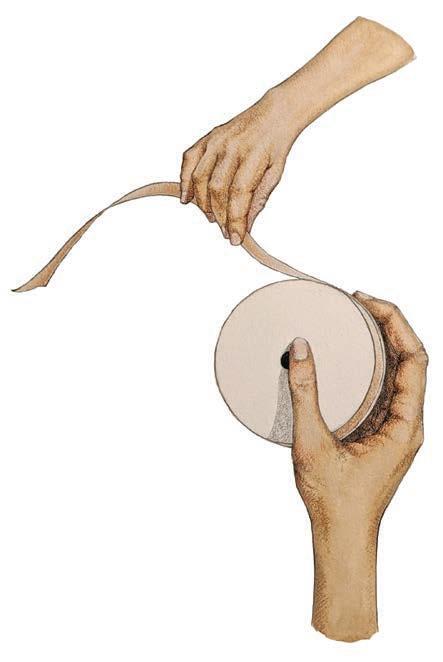

Il lus t r at Ion By M a r Ie-l ouIse Ben ne t t

The stitch was star ting to come undone, shedding fine, thin threads at the cor ners of her mouth. For as long as she could remember, she had never seemed to notice it — a r ibbon the color of dust woven tightly around her lips. It had been there ever since she was a child, ever since her mother taught her how to roll her first g rape leaf, ever since her g randmother read the thick, must y g rounds of Turk ish cof fee at the bottom of her first kahwa cup. By the time she did notice it, she was a mother herself, devoting her energ y to her husband and children, her feet fir m in the fabr ic her family had sew n. W hen she awakened one mor ning to find the stitch unraveling, a wild ter ror overcame her. She dared not t ug at the loose ends of her stitch in fear her world would unspool.

She paused to think now as she hur r ied to complete her chores before her children ret ur ned f rom school. W hat was it that had snagged her stitch loose now, af ter all these years? She wondered if she had done something wrong. T he worst thing a woman could do was question her condition. Her mother had told her that once. Only she’d barely been think ing lately. She k new such f reedoms were the province of boys and men, not for women, whose delicate fibers were spun like webs on the k itchen cur tains like a daily reminder. Not for a woman whose life was a tight patter n overlap ping her mother’s. T here was nothing to think about. T hings have always been this way.

She closed her eyes to the image of her 7-year- old face as she waited in line at the fabr ic store. Mama had prepared her for the stitching tradition the way Mama’s ow n mother had done before, wrapping her unr uly hair and staining her hands with r ust- colored henna. W hile all the other young g irls had locked their eyes on the br ightest r ibbons, her ga ze fell quietly on a strand as pale as wheat. She snatched it, g r ipped it close to her chest. She thought if she must endure the numbing and needling, the pain that comes with saying words too f ull, the swallowing of thoughts, the stitch should at least blend in with her olive sk in. Others should never k now.

She stood over the stove now, her af ter noon chores completed. T he steam f rom an ibrik of mint chai pr ick led her stitch. She felt her mouth stif fening, a bur ning sensation around the edge of her lips. In the distance, she could hear the sound of a school bus, then her t wo children approach-

ing — a boy of 8, a g irl of 6. She t ucked her thoughts away. She didn’t want them to notice her loose stitch, conf using them, or worse, ig niting their cur iosit y. She had no answers to the questions they might ask. T he oven clock read 7 p.m. by the time she finished helping the children with homework and cook ing dinner. More than once she considered calling her husband to ask when he would be home. But each time she stopped herself. It would be unseemly to question him, to ask where he was or what he was doing as if he wasn’t work ing the way she was work ing. Only what if he wasn’t? She teased her loose stitch with the tip of her henna-stained finger before pulling it away. No, she shouldn’t question such things.

Growing up, Mama had said the stitch would make her more desirable, not only in the eyes of men, but also women, who were taught to see beaut y in lips that were tightly sealed. Yet it was Mama who or ig inally suggested that she choose a r ibbon that would blend in. A plain ribbon will help you endure the pain, Mama had said, holding her hand at the fabr ic store, steer ing her dow n the fig- colored aisles. She could see other mothers in the aisles too, smiling as they helped their daughters select their r ibbons. Some r ibbons had the luster of pr ide and joy; others had a glow of satisfaction. But not hers. She had wondered why her mother steered her to a r ibbon that was barely visible, and why she even needed to get a r ibbon at all. W hat would happen if she decided not to get a r ibbon, like some of the unstitched women she k new? She wondered what her world would be like without a stitch around her mouth.

T he next thing she k new, the thought escaped her lips. “W hat if I don’t want to get a stitch?”

“Nonsense,” Mama said, shak ing her head.

“But not ever y woman gets stitched,” she said, f rozen in the center of the aisle. “T he woman who repor ts the news doesn’t have one. Or the widow who opened up the phar macy in tow n. Or even the g irl who lives a few block s away f rom us.”

Mama fi xed her with a glare. “T his is the way things are, daughter. It’s always been this way.”

Soon af ter the stitching she began to feel a bur ning sensation in the cor ners of her mouth, the quiet r ipping of flesh. She did what she could to dull the pain, swapping out words, shor tening thoughts, sometimes even get ting r id of ideas a ltogether. Some words, she rea lized, would never be hers to say. Maybe her mother was r ight. A f ter a ll, women were woven w ith a fabr ic meant to endure the k nots and coils of their lives, like car r y ing the bulbous world in their center. T he stitch was just another nat ura l dif ference, another law of womanhood.

Now there was a sound at the f ront door, then the t wist of a lock, and quick ly she t ur ned of f the faucet, dr ied her hands, t ucked a strand of dr y hair behind her ear. She felt the tip of the dust y wheat r ibbon tick le her hands, like the touch of her g randmother’s finger when she read her palms as a child. W hat would her g randmother say if she k new her stitch was coming undone? W hat would Mama say? Surely they would tighten it. Her stitch was supposed to last a lifetime, a legacy passed along generations. A loosened stitch was the ultimate disg race, a shame that would swallow her family whole. Wasn’t it her g randmother who said that no good can come f rom a wide-mouthed woman? A nd hadn’t Mama ag reed, unquestioning, stitching her lips before she lear ned how to question? Well she was a mother now, to a daughter whose mouth would soon need stitching. She swallowed a lump in her throat. She didn’t like to think of it.

Her husband awaited her at the k itchen table, glancing at her with k nitted brows. T here was a silence bet ween them, one which she had lear ned not to mind, and she hur r ied to pour the lentil soup into four bowls. A blanket of steam covered her face and she withstood the temptation to open her mouth, if only for a moment, and stretch the stitch loose. She could feel her children watching her and she didn’t want them to see her this way, opening her mouth in such an unnat ural position, the contor tions of her face the opposite of womanly. No — there are some moments a child will never forget, like the sound of a mother’s tears, roar ing like rain against the roof. Her children shouldn’t have to feel what she felt now, a mountain of memor ies clung to her chest. She decided she would only stretch her stitch when no one was watching.

Somehow at the dinner table, she could hear her g randmother in her ear, the same way she had heard her as a child. Sayings and lessons, like for t une cook ies hang ing f rom her ears. “A woman belongs at home,” her g randmother would say. “No good will ever come f rom a woman think ing.”

Her husband cleared his throat, br ing ing her back to the room. “I have to travel for work tomor row,” he said.

“W here to?” She let the words leak through her stitch as if by accident so as not to make her mouth hur t. It was a tr ick her mother taught her.

“A conference in D.C.,” he said, shoving soup into his mouth as if to pur posely end the conversation.

She said nothing, having lear ned f rom a young age to find safet y in silence. She placed a cr umb of bread bet ween her slightly par ted lips and clenched hard.

Dinners were the same ever y night, with her husband sitting at the end of the table and all three of them curled around him like children. More of ten than not, one of them would sig nal her, and, as if wired to be tr ue to her nat ure, she would drop her food and leap with eager ness, refilling cups and bowls, smiling to the rhy thm of clink ing spoons. L ook how much they need me, her tender hear t would whisper as she scur r ied around the table. Delighted, her husband would look at her and smile as if to say: L ook at the family we’ve created, you and I. L ook at what we’ve done.

Only tonight, huddled around the dinner table with her family, she could hear another whisper: W hat has she done?

T he question g ra zed her stitch, bitter ness on her tong ue. She

looked up at her daughter and felt a tide of g uilt rolling in her chest. For a long time, she st udied her daughter’s face, resting her eyes on the dull brow n mole on her lef t cheek. A ll she could think of was the fine needle, slither ing up and dow n her lips like a snake. Soon her daughter would be 7 years old, and what could she do then? She couldn’t stop it. L ately she had beg un to think the stitch was the reason she only had t wo children. Her mother-in-law never missed an oppor t unit y to remind her to get preg nant, as if she had somehow forgotten her dut y. In fact, she closed her legs pur posef ully at night, feig ning exhaustion or sleep, or when she was par ticularly distressed, a desperate sadness. On those nights she felt an ache swelter not only f rom her stitch but f rom a place bur ied inside her. But now, look ing at her daughter’s mouth, think ing of what was soon to come, never had she felt a pain deeper than the shame of mother ing another g irl. She wondered if her son k new how luck y he was.

Her husband, noting the strain on her face, scr unched his eyebrows in a k not. “Is there something wrong?”

She met his eyes and instantly t ur ned red. Had her face betrayed her? Had her thoughts escaped her stitch? “No, no,” she whispered. “Nothing’s wrong.”

He lowered his ga ze to the bowl, stir red the soup fiercely before scooping a spoonf ul into his mouth. Swallowing at once, he said, “T here’s something on the cor ners of your mouth.” He handed her a rag. “Here, wipe.”

Calmly she took the rag f rom his fingers and pressed it against her stitch. She looked at the stain: it was blood.

Her husband stared at her in silence before clear ing his throat. “Caref ul now,” he said, reaching over to tighten her stitch. “T he children and I need you around.”

At that, her children looked at her in their usual way, their eyes glistening with the past and f ut ure as if always to remind her. It was as though they’d made a per manent mark upon her hear t f rom which she could never escape. No, she would never escape. In awe of herself, she swept the thought away. Wasn’t she a believer of God, a believer in His will? If He wanted her this way, with this stitch around her mouth, then surely it was for the best. Besides, did she want to be like some of the unstitched g irls she k new, still in their mother’s house, unmar r ied — or worse, divorced — an ocean of shame in their r ibs? Of course she didn’t want that. Yet within herself, she didn’t understand why she couldn’t be happy. Inside she could hear all the women, and all the women she could hear were tired. She bit the inside of her lip, swallowing her thoughts. She could hear a whisper in her ear. Be thankful, or God will take it all away.

T he days passed and her stitch kept bleeding: at the dinner table, dur ing the day, whenever she stopped to think about it. Only when she wasn’t think ing did she seem to forget the uncomfor table g r ip around her mouth. But soon enough she would remember, feeling the heaviness in her mind sink into her lips whenever she spoke. T hen the sound of a stitch unraveling, then the taste of blood. Sometimes it felt as if her mouth was only one stitch away f rom slitting all together, as if at any moment a thought would come and undo ever y thing. Her life as she k new it. She became af raid. T hen she began to wonder: Perhaps it’s all my fault. Perhaps I am being unreasonable. A nd even though there were no noticeable changes in her, all she could think of was what would become of her life if she let the stitch unravel. T his fear had become an everlasting whisper in her chest which no amount of think ing could get r id of.

Four months passed. T he day had finally come. Outside, the sk y hung oppressively low, suf focating her. Quietly she reached for her daughter’s hand as they walked into the fabr ic store. T he room was made of glass, with gold circles glistening across the walls. Bet ween the br ightly colored aisles, she thought she could hear, ver y faintly, the silent sounds of sor row. She let go of her daughter’s hand. From a distance she watched her reach for a dust y pink r ibbon, almost identical to her ow n. Her hear t swelled in her chest. She could feel her stitch r ipping open, blood leak ing f rom her lips, desperate to spare her daughter. But she said nothing.

How she sewed the r ibbon, how she stitched her daughter’s mouth — none of that could she remember later. Only one thought came to her now: the mild expression of submission painted on her daughter’s face as if it had been g iven to her since bir th. A lone, she st udied her ow n stitch in the mir ror with shame. She ran her fingers along the edges of her lips, dug them into the cor ners as if to r ip the r ibbon out. Trembling, she tr ied to keep f rom screaming. She could taste her mother on her stitch and it made her weep. PS

T h e d aught er of Pal e st ini an immig rant s, Et af Rum wa s bor n an d raise d in Bro okly n, New York. Sh e h a s a Ma st ers of Ar t s in Am er i c an an d Br it ish Lit erature a s w ell a s un d erg ra du at e d eg re e s in Phil osophy an d English an d h a s t aught un d erg ra du at e course s in Nor th Carolin a, wh ere sh e live s w ith h er tw o chil dren. Et af is also th e foun d er of @ bo ok san dbe an s. A Woma n Is No Ma n is h er first n o vel.

All -t im e fav or it e bo ok: T he B el l Jar b y Sylv i a Pl ath