42 minute read

Golftown Journal By Lee Pace

That Sinking Feeling

When your world goes sideways

Advertisement

By lee pACe

It’s a golf shot, as Ebene-

zer Scrooge might say apropos of the holiday season, that reeks of an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of underdone potato.

All is right with the world — the sun is warm, the sky is crystalline, the perfume of freshly mown grass permeates the air. The foursome’s in high gear — the bets are made, the jabs are flying, the competitive juices flowing. One-fifty to the green, nice lie, pull the 7-iron, imagine crisp contact and visualize a perfect ball flight, a waggle, a trigger, good extension, sweet tempo . . .

And then a nauseating clunk.

Instead of boring high into the wild blue yonder, the ball flies out of the right corner of your field of vision, into oblivion and certain death.

Silence from the guys.

Golf’s version of Armageddon: the shank.

It happens to the best of them.

Webb Simpson was on the eighth hole at Medinah on the final day of the 2012 Ryder Cup. He needed to hit what he termed would be a “smash 8,” got a little ahead of the ball and shanked it way right, in the direction of the fourth hole.

“I did the math and figured out that was about where Tiger was,” Simpson says. “I thought they’d have to move all those people and make a big scene. It would make no sense to Tiger, and he’d have this on me for the rest of my life. We were in the locker room afterward and Tiger came up to me and said he had a question.

“He said, ‘The wind was tricky today. Where was it blowing on eight?’ He was smiling. I knew he had me. We still talk about that.”

Ian Poulter has hit more shanks than he cares to remember, many of them on the biggest stages in golf. There was the el hosel while in contention at the 2015 Honda Classic, the duck slice at the 2017 Players Championship and the wide right in front of an unforgiving gallery at the 2018 Waste Management Phoenix Open. You can find them on YouTube if you care to venture into that cauldron of horrors.

“I’ve had a number of them at inopportune times,” says Poulter, who’s actually a good sport in talking about a shot that many golfers refuse to address by the s-word name. “I’ve hit a shank on almost every par-3 at Augusta. I tend to move my head slightly forward and my weight gets a little too close to the ball.”

Jack Nicklaus hit a shank on the 12th hole in the 1964 Masters that flew so far right, it didn’t even get wet in Rae’s Creek as it crossed the fairway.

“I’ll never forget the tension in my right arm,” Nicklaus says. “When I swung, my right arm just dominated. It never broke down.”

Johnny Miller hit a shank in the 1972 Crosby Clambake and it haunted him for years. When he won the U.S. Open at Oakmont the following year, he played the back nine while

Foxfire Golf Club

THE RED FOX COURSE THE GREY FOX COURSE

The member’s favorite, this Pinehurst golf course offers wide manicured fairways and large elevated fast rolling greens. Fairway bunkers are strategically placed to grab the wayward shot and there is no lack of sand guarding the greens.

Widely considered the most challenging course, the Grey Fox features hilly terrain, several doglegs and towering pines. Golfers must avoid the sand and position the ball on the proper side of the fairway so that they get the best approach angle to the small greens.

MEMBERSHIPS AVAILABLE STARTING AT $265/MONTH For more information please contact: Brad Thorsky, PGA, Director of Golf

Foxfire Golf and Country Club • 9 Foxfire Blvd • Pinehurst, NC 27281-9763 • 910 295-5555 • bthorsky@browngolf.net

Merry Christmas

160-L Pinehurst Ave. • Southern Pines, NC comfortstudio.net • 910-692-9624

VOTED THE WORLD’S MOST COMFORTABLE RECLINER

The Sandhills Original TEMPUR-PEDIC Showroom

Discover How Comfortable Life Can Be.

Nothing helps you relax and unwind like the unmatched comfort of Stressless®. You can feel the difference in our innovative comfort technologies, including BalanceAdaptTM, which allows your body to automatically and effortlessly adjust to your every move. Do your body a favor. Sit in a Stressless and let it discover the ultimate comfort that it has been missing.

LOCATED ON PINEHURST AVENUE BETWEEN ARBY’S AND LOWE’S HOME IMPROVEMENT shooting a 63 with one swing thought, “Don’t shank it.”

Miller says the hardest shot in golf is the one after a shank.

“The clubface looks the size of a pea while the hosel looks as big as an elephant,” Miller says. “I contended in tournaments probably 50 times after that, and every time I was worried about shanking.”

Tommy Bolt was once playing in a pro-am with a man who was very nervous on the first tee. He managed to get his first drive in play, but he shanked his second shot. Bolt gave him a word of advice, but he shanked his next shot as well. Bolt gave him something else to try, but the result was yet another shank.

“Tommy, what should I do?” the man wailed.

“Pards, just aim to the left and allow for it,” Bolt said.

Charles Smith was warming up on the practice tee before his semifinal match in the 1960 North and South Amateur at Pinehurst. He hit a shank with his wedge. Then another. Then another.

“Your hands start to sweat and you get that awful feeling in your stomach,” Smith says.

Smith refused to pull the wedge out of the bag the rest of the day. From a hundred yards in, he either hit a choke-down 9-iron or a hooded sand wedge all day. He won the match and went on to collect the title the next day.

“I wasn’t going to risk hitting a shank,” Smith says. “God, what an awful feeling.”

Former PGA champion Jerry Barber designed and manufactured a line of irons that were supposedly shank-proof. Instead of having a round hosel connecting the clubface and shaft, the front of the hosel was flattened. So even if you connected hosel-to-ball, the ball presumably would go forward instead of sideways. The company is now out of business, but the 800 number used two decades ago still gets calls from the afflicted.

Purvis Ferree, the longtime head professional at Old Town Club in WinstonSalem, was hounded by the shanks in older age as his swing flattened with the inevitable rounding of the body and less-

ening of flexibility. He eventually played with two of Barber’s “Golden Touch” wedges, a no-shank 7-iron for chipping, and a bag full of fairway woods.

“Father was such a wonderful teacher, but the shank almost reduced him to a spectator,” says son Jim, himself a club professional and tour pro on the PGA Tour and Champions Tour. “There were times he could not hit a solid golf shot. One day at Roaring Gap, he gave his irons away to a caddie when he got to shanking.”

In one celebrated story they still tell around Old Town, Purvis went out for a regular match with Malcolm McLean, the trucking magnate and owner of Pinehurst Resort for a decade in the 1970s. The bet was that if McLean could win any one hole, he won the match. On the first hole, Ferree shanked several shots around the green and wound up in the very divot he made with his first shank. He picked up and conceded the hole and the match to McLean.

Jim Ferree was a club professional in Pittsburgh in the 1980s when one of his members, a doctor, saved his golf game by acquiring a set of the Barber irons. When the member read in Golf World that Barber’s company was going out of business, Ferree helped him acquire a backup set in case something happened to the original clubs. Several months later, Ferree was at the doctor’s home for a cocktail party and wondered if the man still had the irons. The doctor led Ferree into a walk-in vault in his bedroom, where the irons were tucked away along with his wife’s jewels and furs.

Just goes to show you the lengths a man will go to protect his cure to the abominable shank. If you’ve never hit one, count your blessings. If you have, please don’t let this harmless little narrative pollute your mind the next time you address a 100-yard approach. PS

Lee Pace has written about golf in the Sandhills for three decades. His newest book, Good Walks — Rediscovering the Soul of Golf at 18 Top Carolinas Courses, is available at area bookstores and through UNC Press.

Now Under New Ownership But we hope you never notice!

Still

BEST STEAK IN TOWN

Give the gift of the best steak in town! Buy $100 in gift cards get a $10 bonus

Monday-Thursday 5p - 9p & Sat/Sunday 5p -10p Lounge 5pm-until 910-692-5550 • 672 SW Broad St. Southern Pines, NC beefeatersofsouthernpines.com

Let's Make the Holidays Bright

Olmsted Village Patio

244 Central Park Ave. #222A Pinehurst (next to True Value Hardware) 910-420-2501 olmstedvillagepatio@gmail.com Hours: Closed Monday Tues-Fri 11-7 Sat 10-6 • Sun 12-6

December ����

Small Prayer

We see this ground as if through a spaceship’s faceted metal eye. Having seen the blue round as small as a child’s ball, having solved just enough of mystery to be lost in what we think we know. We’ve thought to play with it, to make the planet smaller yet.

Now we do with it what we will, forgetting how its vastness left us speechless, worshipping. We lose forest and furrow where we began. And the kindred animals have begun to leave. The water’s gone that married time and loved the stone into a canyon’s grace. We’ve forgotten how to stay — how to say: this place.

Let the earth grow large enough again that only clouds and stories can encircle it entire. Let rockets land for good, satellites fall dumb, and wires unspan enough that distances grow wide to dwarf our wars. May mystery loom large enough again to answer prayers and keep us. — Betty Adcock

Betty Adcock is the author of Rough Fugue.

Bring Us Some Figgy Pudding

Simple and elegant holiday brunch ideas

Story and PhotograPhS by roSe Shewey

Festive meals among family and friends are the most magical of holiday traditions. Give me a Christmas brunch and I’ll be as joyful as the Sugar Plum Fairy in the Land of Sweets. If you are blessed with young children on Christmas morning, you know that an early pot of coffee or a cup of tea is the most you’ll have time for until the presents are unwrapped and ooohed and aaahed at. Or, if you’re celebrating among grown-ups, an unrushed, peaceful start to the day can be a grand idea. All of which makes Christmas brunch an excellent choice on one of the brightest, most colorful and cheerful days of the year. To spend less time in the kitchen and more time in the moment, with the people you love, gather inspiration from these simple, eye-catching dishes that require few ingredients and even less time to prepare.

GinGerbread douGhnuts with amaretto ChoColate Glaze

Doughnuts should be a staple in every brunch spread, no doubt about it. A basic doughnut recipe can be adjusted easily to feature the flavors of the season. To transform ordinary doughnuts into a winter holiday treat, simply add gingerbread spice mix to the dough and, once baked and cooled off, dip in melted white chocolate infused with amaretto. Sprinkle with crushed almonds and sparkling sugar to add a touch of winter magic to your buffet.

eGGnoG Chia Parfait

A spectacular make-ahead option for Christmas morning is eggnog chia parfait. Nothing says Christmas more than eggnog for breakfast! To every one cup of liquid, add 1/4 cup of chia seeds; allow to rest for a few minutes, stir and refrigerate overnight. Layer with müesli, chopped nuts, seeds, chocolate mousse, compote, jam or fresh fruit of your choice and top with whipped cream. The possibilities are endless, so let your creativity run wild.

Yorkshire PuddinG breakfast bake

A take on the traditional Yorkshire pudding (which is similar to the American popover), this is a simple yet striking — not to mention scrumptious and satisfying — dish to serve your family and friends on Christmas morning. The base is made with just eggs, flour and milk, and takes minutes to whip up; add any breakfast ingredients of your choice, such as bacon, sausages or tomatoes and bake in the oven for 15-20 minutes or until the egg mixture is cooked through.

Green shakshuka with PoaChed eGGs

Traditional shakshuka is not just a feast for the eye, it’s an incredibly aromatic dish for all those who have a penchant for Mediterranean spices. To mix it up, try a green version of shakshuka. Instead of the tomato base, use layers of green vegetable, such as leafy greens, zucchini, broccoli and peas, then season with green harissa, paprika and cumin. Finish by cracking eggs right into the skillet and cook until the whites are set. Serve with toasted bread.

Potato waffles with smoked salmon

Potato waffles are a fabulously sophisticated alternative to ordinary hash browns. To save time preparing a hash brown mixture, you can use previously frozen potato puffs or even a leftover mashed potato mix. Potato waffles will cook in minutes and make a hearty base for a variety of toppings. Smoked salmon with a dollop of crème fraîche garnished with capers and roe is a holiday-worthy combination. Or, you might find your own favorite mélange.

winter Pavlova with Clementines

Pavlovas are quite the showstoppers and require few ingredients to make, mainly just egg-whites and sugar. While pavlovas can be a bit temperamental (you want to beat the eggs just right), they are exquisitely light and airy compositions that can be made a day in advance and dressed up with cream and fruit right before serving. Top your pavlova with whipped cream, curd and any seasonal fruit of your choice, such as clementines, oranges, figs, pomegranate or pear. PS

German native Rose Shewey is a food stylist and food photographer. To see more of her work visit her website at suessholz.com.

The ForgoTTen Boyd

The story of an exceptional kid

by StePhen e. Smith PhotograPhS from the weymouth Center arChiveS

Dan, Katharine and Jim Boyd Jr.

“The best of that whole Boyd bunch was Dan, the one who was killed in a motorcycle accident in San Francisco,” Glen Rounds said while lounging in his front yard on a sunny spring afternoon 30 years ago. He was parsing the James Boyd family, the “first family” of Southern Pines, the clan responsible for many of the aesthetic and cultural pleasures our quaint hometown offers.

“The older son, Jim, was something of an oddball,” Rounds continued, “but Dan . . . Dan was an exceptional kid.”

When Rounds spoke, I listened. Intently. In addition to authoring 100 children’s books and receiving a slew of state and national awards for his writing and illustrating, Rounds had his arthritic fingers on the pulse of Southern Pines. He knew what there was to know about everyone in town worth knowing about, and he served up his edgy opinions freely and with an occasional sprig of rancor and a dash of humor. Any praise, however slight, he might lavish on Daniel Boyd, the second son of historical novelist James Boyd and his wife, Katharine, was a high recommendation indeed and worthy of investigation.

“Dan was awarded the Silver Star during the Battle of the Bulge,” Rounds went on, “and when he got back in town, he never once mentioned it.”

I knew nothing of Dan Boyd, so during my next visit to the Southern Pines Library, I plundered through fusty back issues of The Pilot bound in bulky, outsized volumes, and discovered the January 1, 1959, front page headline: “Daniel Boyd Killed in California Last Tuesday in Traffic Accident.”

The timeworn newsprint was crumbling and much of the story was missing, but the essential facts were there: “Daniel Lamont Boyd, 34, the son of Mrs. James Boyd of Southern Pines, was fatally injured Tuesday of last week (Dec. 23, 1958) in San Francisco, where he had made his home.” Boyd was homeward bound from the city center when a car crossed the yellow center line and struck his “motor bike” (a lightweight scooter of some variety, possibly a Vespa) headon. Dan was transported to the hospital, where he died without regaining consciousness.

The article also noted that Katharine Boyd, publisher of The Pilot, flew to San Francisco as soon as she received word of her son’s death, and that “News of the tragic accident was received with great sorrow in the community.” Although Dan hadn’t lived in Southern Pines in several years, he had “maintained earlier friendships with many people.”

If Rounds wasn't exactly correct about the motorcycle, he was spot on when it came to Boyd’s military record. Dan served with the 60th Engineering, 35th Infantry Unit, which fought from Normandy, through the battles for SaintLô and the Bulge — 78 years ago this month — to the end of the European campaign. It was during the Battle of the Bulge that Dan distinguished himself and was awarded a Purple Heart and the Silver Star for gallantry under fire.

The Army doesn’t retain records detailing the courageous actions of individuals who have been awarded the Silver Star, but the Friday, Feb. 9, 1945 issue of The Pilot reprinted an official press release:

“Corporal Daniel L. Boyd, 34677486, Corps of Engineers, United States Army, for gallantry in action near France on 13th December 1944.

“During the crossing of the River near , Corporal Boyd was in charge of an assault boat operating in a sector which was subjected to intense machine gun fire from enemy emplacements located only 150 yards from the river. When he saw a nearby boat capsize in mid-stream after receiving a burst of machine fire, he immediately paddled his boat to the scene and rescued five heavily clothed soldiers from drowning in the swift current. After he had brought the men to the friendly shore, he started to assist them to an aid station when one of the men collapsed as a result of a wound he had suffered. Corporal Boyd placed

Dan Boyd

him in a sheltered position, administered first aid, and then continued to the aid station with the other men. Finding a shortage of medical personnel, he personally returned to the wounded man he had left behind, in the face of withering enemy fire, and with the aid of a litter bearer, succeeded in evacuating his comrade. Corporal Boyd’s intrepid deeds and resourceful performance in the face of heavy odds were responsible for saving the lives of five of his comrades and are in accord with the finest tradition of the United State Army.” The January 1959 Pilot notes that “With fighting going on across the river where American units were isolated, Boyd went out, found one of the engineers’ boats and, under heavy fire, ferried across sufficient men to win the action.”

Valor in military service was nothing new to the Boyd family. Novelist James Boyd Sr. served as an ambulance driver in France during World War I, and Dan’s cousin, Seaman 1st Class John Boyd, who had grown up in what is now the Campbell House, died in the Battle for Guadalcanal when the USS Barton, the destroyer on which he was serving, was sunk in a night action in November 1942.

My curiosity concerning Dan Boyd’s life and death might have ended there, but Rounds’ recommendation resonated with me whenever I attended a cultural and social event held at the Weymouth Center for the Arts & Humanities. A few years later, I was researching James Boyd’s relationship with F. Scott Fitzgerald and Sherwood Anderson in the Firestone Library at Princeton and the Southern Historical Collection at UNC when I happened upon letters from Dan to his parents, chatty missives about life at boarding school, football games and, oddly enough, railroads. His letters were peppered with allusions to the trains and drawings of locomotives.

The mystery of Dan Boyd’s life unraveled further when Dotty Starling, Weymouth’s dedicated archivist, lent me a copy of An Oral History of Weymouth. Published in 2004, the history gathered the reminiscences of friends of the Boyd family and the recollections of longtime employees. Many of the details of Dan Boyd’s short life are revealed in those collected memories.

I learned that in the ’20s and ’30s, the James and Jackson Boyd children had grown up together, playing in the pasture behind Weymouth, riding horses, and sharing in the privileges afforded by their parents’ wealth. They all attended kindergarten and elementary school at the private Ark school, initially located on the corner of Ridge Street and Connecticut Avenue on the Weymouth property. (The foundation of the school is still clearly visible, a giant magnolia rising from what must have been the building’s basement.)

Longtime Pilot reporter and editor Mary Evelyn de Nissoff remembered her days attending the Ark in a 2001 interview: “Two English ladies ran it. In the morning they welcomed the children with a handshake and had a cup of tea with them before classes began. In the afternoons the children went down into the basement where there were iron cots . . . where the teachers read aloud to them.” All three of James and Katharine’s children, Jim Jr., Dan and Nancy, the youngest, attended classes with Mary Evelyn. “They (the Boyd children) rode, of course. They were into horses and they smelled of horses. Nancy didn’t, but Dan did.”

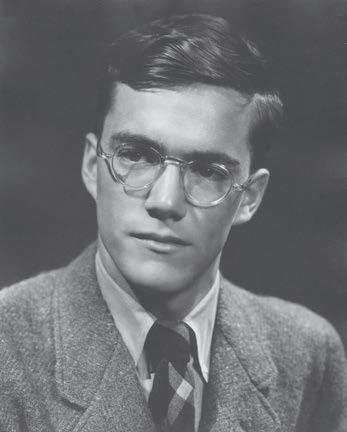

A life of privilege notwithstanding, the Boyd household was not always a peaceable kingdom. Jim Jr. and Dan, brothers of very different temperaments, often argued, and their mother had difficulty maintaining domestic harmony. In a scrapbook preserved in the Weymouth Archives, an unidentified family poet recorded the domestic discord in rhymed iambic pentameter: Dan Boyd before going overseas

Thus while Dan offers up his soul To knowledge and each day grows thinner, James lies in bed and eats his dinner; And while Dan toils o’er Latin grammar James turns out mediocre verses Of fulsome amatory tone And sends them round to all the nurses.”

If Jim Jr. lacked motivation, Dan was obsessed — with trains. He decorated his room with railroad posters, collected electric trains, and snapped hundreds of photos of art deco diesel and steam locomotives — massive pufferbellies with all the machinery bolted to their boilers — which are now preserved and cataloged in the Weymouth Archives with other Boyd family papers.

The anonymous family poet also offers a prediction:

That some day, trudging down the track In broken hat and hobo’s breeches, He’ll [Jim Jr.] hear a train behind his back Come rattling over frogs and switches And, looking up as it goes past, See seated in his private car The road’s vice-president, D. Boyd, Smoking a fifty-cent cigar!”

Dan and Jim Jr. were eventually shuffled off to Millbrook School, an academy for students in grades 9-12 located in Millbrook, New York. During those years, they wrote letters to their parents that conveyed a strong sense of family and a guarded affection for one another. Dan wrote about trains and drew locomotives on Millbrook stationery letterhead.

After completing their studies at Millbrook, Dan matriculated at Princeton, his father’s alma mater, while Jim Jr. attended UNC. When the war interrupted their studies, Jim

joined the Coast Guard and Dan enlisted in the Army and fought in decisive battles in Europe. After the war, the brothers completed their degrees and Dan married Rhoda Whitridge in 1948 and went west to work with the Southern Pacific Railroad in Eugene, Oregon, eventually settling in San Francisco.

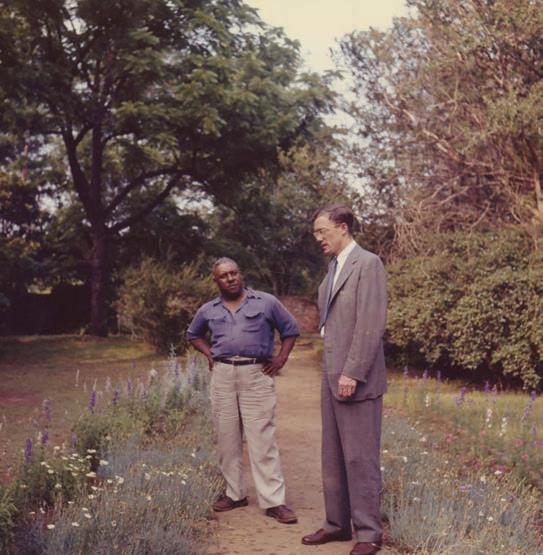

In 2002, Weymouth board member Bea O’Rand interviewed longtime Southern Pines luminary Voit Gilmore, who knew the Dan Boyd family well in the 1950s: “We knew of his connection with his very generous work with the arts council and arts groups in San Francisco. We knew the exact street where he was on his motorbike and got hit. Every time I go by that intersection now, it just breaks my heart that that happened. It was a steep hill on Polk where you come up and go over. The problem always is that if the traffic light goes against you and you’re going up the hill you have a terrible time, you need to get over to the middle of the intersection which is what he did and got hit because of a car.”

Flossie Carpenter, a longtime employee of Katharine Boyd’s, recalled the effect Dan’s death had on his mother: “Now that’s when Mrs. Boyd went off, the morning that she got the message that he had been killed. Her mind was no more good. She tried to do but she couldn’t. . . . She stayed that way for about three years.”

Mary Evelyn de Nissoff, who suffered tragedy in her own life, keenly comprehended Katharine’s suffering. “ . . . I can understand what she was going through. She never got over it, because it leaves this great hole in your stomach that is never filled up.”

As a family, the Boyds participated in bettering the community in which they lived. Katharine contributed anonymously to the education of many local children. The family gave us the Weymouth Woods Sandhills Nature Preserve with its 7 miles of hiking trails and visitor center and exhibits, contributed to the Southern Pines Library, maintained what is now the Weymouth Center for the Arts & Humanities, and provided funds for the Boyd Library at Sandhills Community College. They worked to beautify the town and protect the pines that line our streets and shade our homes. The oldest living longleaf pine — its seed germinated in 1548, a survivor now of what was once the largest ecosystem in North America — thrives still on the Weymouth property.

Dan Boyd with gardener Hilton Walker at Weymouth

In 2002, Rhoda Boyd, Dan’s widow, was driving with her granddaughter outside San Francisco when a redwood fell on her car, killing her instantly. Her granddaughter survived without injury. Dan and Rhoda Boyd are interred in Cypress Lawn Memorial Park in San Mateo County, California, far from Dan’s childhood home.

On that spring afternoon 30 years ago, Rounds, who knew something about humor and its understated uses, continued lauding Dan Boyd, offering up examples of his keen wit and artistic nature. As the afternoon wore on, the Southern Pines Middle School dismissed, and crowds of children began wandering up Ridge Street.

“Let’s go inside and have a drink to Dan Boyd,” Rounds suggested. “I don’t like to sit out here when these kids go by. They make too much noise.” Then he smiled. “But I’ll tell you what: When they’re gone, I go out and pick up their pencils.” PS Stephen E. Smith is a retired professor and the author of seven books of poetry and prose. He’s the recipient of the Poetry Northwest Young Poet’s Prize, the Zoe Kincaid Brockman Prize for poetry and four North Carolina Press Awards.

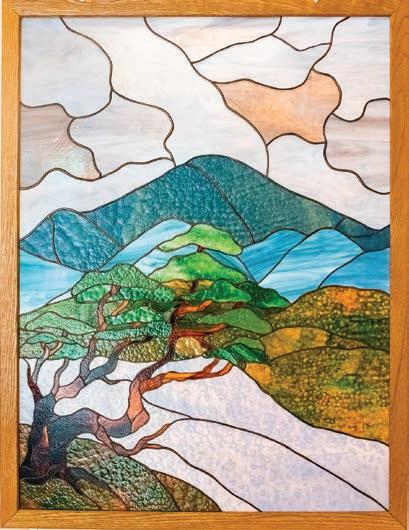

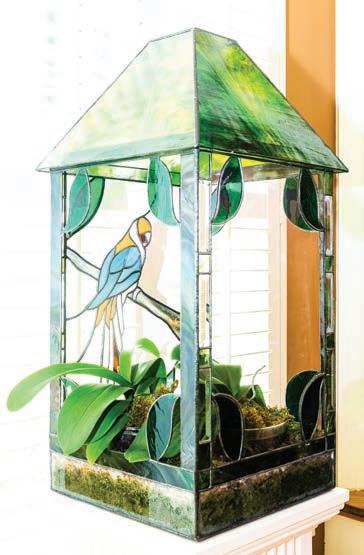

Through RoseColored Glass

The art of working with stained glass

by Jenna biter ’ PhotograPhS by John geSSner

An oversized sheet of white craft paper unrolls across the worktable. “So, what I do,” Sarah Cawn says, her voice trailing off, distracted by a half-open box. “This is a big lamp I’m supposed to repair.” She lifts a cardboard flap and fingers the dome of a Tiffany-style glass shade.

“OK,” she says, gathering herself to explain the process of making beautiful things with stained glass. “This one I just finished.” She points to a drawing on unfurled paper. The contours of wavy-edged poppies and their swan-like stems arc through rectangles configured like the eight windowpanes they represent.

A gilded light casts itself across the drawing. Cawn points at the studio ceiling. “When we built the house, I had the builder box up the skylight so I could put that in there,” she says, her head tipped back. Above her a glass cupola of yellows and browns, trimmed in a filigree of rose and sea foam, warms the drawing below, willing it from the second dimension into the third.

Each section of the drawing, from the size of a button to the palm of a hand, whether it represents a petal, stem or sliver of background, wears a number as its name tag, all the way through 332, like a grown-up’s paint-by-number.

Cawn starts with the obvious. “I roll paper out and cut off as long a piece as I need.” She traces an index finger around each rectangle. “I had already drawn out the perimeters of each window, then put it up over there.” She points to a blank wall on the far side of the studio, half hidden by a table crowded with a collection of glass baubles: iridescent charms reminiscent of abalone, an amber chest overgrown with irises, a heart-shaped box, stacks of colored glass sheets, and a retro lampshade turned on its head.

She plucks the heart-shaped box from the menagerie like a client perusing the wares at a fine arts bazaar. “This is something that I inherited from somebody that got out of the business,” she says, holding the red vessel up to the light. “I thought if I fixed it, maybe I could — I don’t know.” Cawn turns the box over in her hand and inspects the soldering. She wrinkles her nose.

“It looks kinds of crummy, though. I don’t really want to sell it, so I probably should just junk

it.” She sets the box down. “I just don’t feel right about selling something that isn’t mine.”

Cawn thumbs through colored glass sheets as if they’re playing cards, and she’s searching for the right one to start building a hand. Clack, clack. Each glass sheet is a different color, striated like the hard insides of a geode. Clack. There are emeralds and milky jades, electric blues and smoky blacks. One sheet is a galaxy of amethyst and mulberry; another swirls angrily like the eye of Jupiter, but in the soft nudes of a conch shell’s aperture.

“I thought it would be fun if I put them together like a patchwork and make cool wall hangings,” she rearranges the pieces like they’re quilt squares, thinking out loud, “if I do the colors right.”

A scarlet macaw perched at the opposite end of the studio stares past Cawn at the half-hidden wall. The bird isn’t real — Cawn made it of glass — but it occupies the space of a live macaw, giving the impression, from the periphery, that it might squawk in its own colorful language.

She points back to the wall where she has tacked up the paper and penciled in the poppy design. “I’m going to be honest now, for the poppies — I do have an overhead.” She describes adjusting the projector until the blooms cast onto the paper create a convincing field of flowers, then she traces the pencil lines with black marker to finalize the design.

Cawn began making stained glass 40 years ago, give or take, at a Maryland shop (whose name she can’t remember and which has since closed) and has, ever since, been polishing her process as if it was, itself, a panel of stained glass.

“For me, it was like a drug,” she says with a shrug. “My husband made me a little workbench down in the basement and, at 10 o’clock at night, he’d go, ‘Are you coming to bed?’”

Through their moves to California, then throughout the Research Triangle in North Carolina, Cawn packed up her glass and tools — marked with a band of cheetah-print tape — and taken her craft with her.

In San Ramon, California, her studio was half the garage. “In the wintertime, I’d have to keep the big glass pieces in the house, so they’d be warm,” she says, explaining that glass can shatter when its temperature rapidly rises or falls.

When the Cawns moved to Cary in the early ’90s, Sarah got her first real studio, but it was on the third floor. She crosses her eyes and groans, “Ughhhhhh,” imagining herself carrying sheets of heavy glass up three flights of stairs. They built their current house, a stone hideaway tucked into the woods just outside of downtown Raleigh, in 1996, and Cawn’s studio is a bonus room above, not in, the garage. An arched windowpane of wispy lines and pastel orbs over the front door welcomes guests into their

home and silently announces the workshop upstairs.

“It started here,” Cawn says of her business, Sarah’s Glass Art, taking off. “In the ’90s everybody wanted stained-glass windows above their bathtub or around their door.” She grins sheepishly. “If I was lucky, they did both.”

Stained glass, and the inspiration for it, infuses the property like a visual perfume. Outside, in the backyard, tangerine, fiery red and pale pink koi glint like glass shards in the afternoon sun as they circle an ornamental pond. One fish resembling a golden dragon, with his trailing whiskers and billowing fins, swims near the surface, as if it were a water-bound Icarus waiting to be immortalized in glass like the scarlet macaw.

Later, the Cawns built a second studio, this one detached from the house, where Sarah makes fused glass, a craft she picked up two decades ago. It’s also where she teaches students to work with stained glass, something she started last year.

With the poppy pattern complete, Cawn traces a copy. “Some people take it to Kinkos, or some place that will copy it, but I don’t know how accurate that will be, so I’ve just never done that,” she says. “And I know, I’ve been told, ‘You’d save yourself a lot of time.’” She waggles an index finger. But why fix what’s not broken?

Keeping the original pattern as a template, she fits a jig — a device reminiscent of a picture frame — around the drawn windowpanes and fixes the jig to the worktable. It is the stage where all the pieces will come together. “Nothing’s going to turn out square if you don’t put a border around it,” she says. “If it’s not square, it will look like crap.”

Cawn cuts apart the copied pattern so she can trace each piece of the design onto glass (black marker on light colors and silver marker on darks), then she cuts the glass itself. To demonstrate, she pretends to trace a shape onto a spare sheet of emerald glass, the color she used for the poppy stems.

Cawn looks up as a schnauzer tears around the corner into the studio, nails clacking against the hardwood floor, legs spinning out. “She’s not really cute because she’s shaved now,” says Cawn, apologizing for Schatzi’s shorn summer coat. She reaches down to pat the gray head. “She’s gotten really finicky, so I say, ‘Just shave her. It’s not a fashion show.’” The 13-year-old dog wiggles her

stubby tail, then retreats to a plush bed in the corner.

“OK, they’re all cut out, and they all fit nicely,” Cawn says, back behind the worktable. She pulls out a spool of copper foil tape and demonstrates lining the edges of cut glass. “You do this all the way around the glass, and you overlap it by a 1/4 inch at the end.”

Cawn smooths the foil, so the entire edge is neatly covered, and a thin line of copper shows on the face and back sides of the glass. The dark patina of the copper will give the stained glass its signature edge. “You do this on all your pieces,” Cawn says. In this case, all 332.

Soldering comes next, then the patina, then a wax and polish to shine the panel. “You take your wax, shake it, pour a little on, wipe it all over, let it dry, and then you buff it with a rag, and you’re done.” She tosses a rag on the table.

“I used to hate waxing and polishing, but it’s such an important part. It’s the finishing touch, and they go, ‘Ohhhhhhh.’” Cawn puts her hands to her cheeks and opens her mouth, mimicking happy customers and, in a way, herself. “To me, there’s just a magical quality about glass.” PS

Shop for Sarah Cawn’s glass art at One of a Kind Gallery, in Pinehurst.

Jenna Biter is a writer and military wife in the Sandhills. She can be reached at jennabiter@protonmail.com.

Touch of the Orient

Aberdeen’s John W. Graham House is a colorful work of art

by aShley walShe • PhotograPhS by John geSSner ChriStmaS Styling by hollyfield deSign

In the late 1990s, Bart Boudreaux was living in Beijing, China, with his wife, Lynel, when a friend invited him to visit Pinehurst.

“It was a lot different back then,” says Boudreaux, a Louisiana native whose work in the oil business had taken him all over the globe. “Very quiet, calm. Not much traffic. That’s what we were looking for . . . especially coming from China.”

Of course, the world-class golf was part of the draw. “Unmatched,” says Boudreaux.

Life in Pinehurst became the pin on the narrowing horizon. In 2012, the couple bought and restored one of the 1895 James Walker Tufts cottages (The Woodbine) in

Old Town Pinehurst, where the couple have lived since Bart’s retirement in 2015.

But this isn’t a story about that house, nor is it a story about Pinehurst. Ultimately, this is a marriage story. It begins with one man’s love of old houses.

“I can’t explain it,” says Boudreaux, trying to put his passion for restoration into words. “I needed to find something to do outside of golf.”

Perhaps his time in New Orleans influenced his taste for old houses. “Not everyone’s cup of tea,” he admits.

Regardless, buying and restoring them became his accidental pastime. In addition to the Pinehurst home, Boudreaux revamped the house next door (another one of Tufts’ original 38 cottages), renovated a 1930s Sears Roebuck on Dundee Road, then flipped one, two, three more fixer-uppers, all in Pinehurst.

Which brings us to his seventh and most recent project: a 1909 Victorian in downtown Aberdeen.

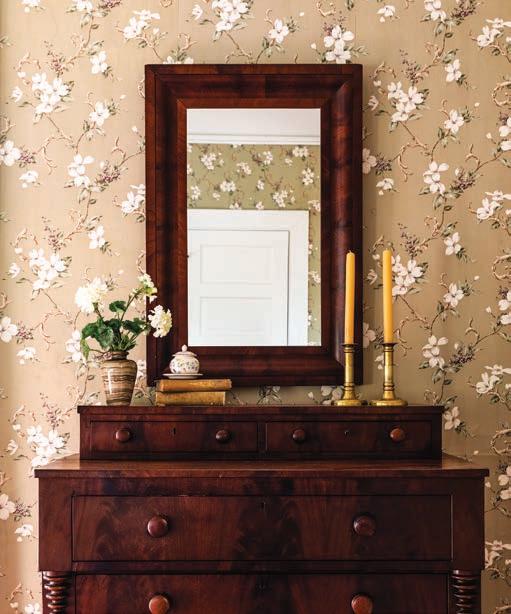

Situated on a spacious corner lot on High Street, the sage green double-pile with the classical Tuscan columns and wraparound porch once belonged to John W. Graham, son-in-law of Aberdeen and Rockfish Railroad founder John Blue. The exterior is grand yet understated, with an air of timelessness and restraint typical of Colonial Revival architecture. Boudreaux bought the National Register property in February of 2021 and devoted one year to its transformation.

“It’s got tremendous character,” he says, noting the 10-foot ceilings and crown molding, the butler’s pantry, the two-story semi-octagonal bay, original dogwood wallpaper in one of the upstairs bedrooms, and five charming fireplaces throughout.

An original stained-glass window defines the nook beneath the half-turn staircase. Natural light floods every inch of the 2,500-square-foot space. Upstairs, transom windows above bedroom doors offer charm and function.

“I fell in love,” he says.

Heart pine flooring was repaired and restored. Old doors and tiger oak mantels, once hidden beneath layers of paint, are now among the home’s most striking features. Ditto the banister, stairs and newel caps.

“Almost killed me,” says Boudreaux of all the stripping. He did what he could himself and hired help to do the rest.

Boudreaux upgraded and reconfigured the kitchen, reintroducing an old entrance and constructing a small island with salvaged beadboard. He retiled and revamped existing baths (one full and one half); added a full bath upstairs; installed new cabinetry and quartz countertops; tinted origi-

nal windows; exposed a bit of brick; updated plumbing, electrical wiring and appliances; replaced ductwork; and insulated the crawl space.

But he didn’t stop there.

Throughout the house, period-appropriate light fixtures (complete with ceiling medallions), fabric and furniture complement the architecture.

“I just love the search for antiques,” he says, which is how he crossed paths with interior designer Jane Fairbanks of The Old Hardware Antiques in Cameron. “I know what I like. Jane’s got it.”

Fairbanks helped Boudreaux outfit two of his Pinehurst homes in American country décor. “What he truly loves,” says the designer.

The interior of the Graham house is distinctly different. It’s an amalgam of color, texture and Victorian-era furnishings with a heavy emphasis on Oriental antiques —a marriage of tastes, his and hers. Flash back to China in the late 1990s.

“The oil company I worked for allowed us to transport one shipping container full of Chinese furniture back to the States on their nickel,” says Boudreaux.

Lynel, who worked as the assistant general manager at the Hilton Beijing, loaded up on ornate altar tables, hand-painted cabinets and intricate Chinese artwork — textiles in particular. Bart took Fairbanks to sift through the haul, in storage for over 20 years. Forgotten treasures were promptly dusted.

“They sort of became the inspiration for everything,” says Fairbanks.

Especially the colors. In the front parlor, coral walls pop against crisp white molding and creamcolored beadboard wainscoting. A hand-embroidered silk opera collar is framed and displayed on the wall above the staircase. Asian accent chairs covered in pagoda-themed fabric flank the fireplace, and a pair of wooden foo dogs (Chinese guardian lions) draw the eye to the quarter-sawn tiger oak mantel.

Beneath the stained-glass, a hinged easel frame displays photos of original homeowners John W. Graham, a cashier and officer of the Bank of Aberdeen, and his bride, Kate Blue Graham.

One wonders what Kate might think of the vibrant paint and forbidden stitch embroidery.

Beyond yellow pine pocket doors — “massive and heavy as led,” adds Fairbanks — coral walls spill into the living room, where a silk rug and custom curtains soften the space with delicate pink hues. This is where worlds begin to collide in a surprising way: an American country cherry corner cupboard (1840s), for instance, opposite a Chinese wedding cabinet featuring traditional brass hardware and a hand-painted imperial dragon.

For Lynel, each piece has a story, like the statuette of Guan Yin (female Buddha), positioned between the living and dining rooms.

“I bought her in a Beijing dirt market from a little blind man,” Lynel recalls. The vendor assured her that the wooden figure was quite old.

“Lǎo de, lǎo de,” he repeated.

It wasn’t. The Buddha split in half a few weeks later.

“Sounded like a gunshot,” Lynel says between bouts of laughter. “She was new, made to look old . . . but I love her anyway.”

In the upstairs hallway, a teak altar table paired with a carved wooden screen make a bold and elaborate statement. The walls? Georgian Green by Benjamin Moore.

Bedrooms are handsomely outfitted. For one, an 1840s maple rope bed with curly

maple headboard. A four-poster bed in another. The third features a faux curly maple queen anchored by an early 1840s blanket chest. Mounted oriental hair pins and an embroidered baby bib (and matching shoes) add color and whimsy.

“It’s just amazing how things can come from so many places and end up working so well together,” Fairbanks says.

The designer played a major role in bringing Bart’s vision for the house to life. “Big time,” he emphasizes.

All parties seem equally delighted by how it turned out. In the past, Boudreaux’s modus operandi has been to revamp and resell. But the John W. Graham house is a keeper.

“Our Pinehurst house is on the market,” he explains.

Towns and dreams change. Bart and Lynel are moving back to Louisiana to be closer to family. The house on High Street will be their vacation home.

“Aberdeen is having a bit of a Renaissance, don’t you think?” says Lynel.

Bart’s golf clubs are there waiting. The house itself — a harmonious blend of tastes — is a labor of love ready to be enjoyed. PS

Ashley Walshe, the former editor of O.Henry, lives up country and is dreaming up her next grand adventure.

ALMANAC December

by aShley walShe

December is a frosted window, a singing kettle, the busying of hands. Beyond the glass, the breath of winter settles upon the still earth like a blanket of glittering lace. The garden withers. The air grows bitter. The cold sucks the life from the glistening landscape.

Yet, for a few precious hours, the wild ones stir.

As the sun thaws the silvery earth, critters emerge from their hideaways.

Birds flit from feeder to swinging feeder.

Deer feast on turkey tail mushrooms; paw for acorns; chomp on chicory and sunchoke roots.

Mice sniff out seeds. Rabbits munch on winter buds. Hawks watch from the naked trees above.

Inside, time is measured by cups of tea — earthy, dark and sweet. The fire crackles. The kettle sings. Quiet hands ache to make things: Sourdough loaves studded with walnuts and dried figs. Gingersnap cookies thick with blackstrap molasses. Stovetop potpourri swirling with pine, orange and warming spices. Winter wreaths woven with wild grape and honeysuckle vines.

Beyond the window, night comes early. The air grows frosty. Critters disappear with the dwindling light.

You stoke the fire, tend the kettle, nurture an ancient knowing growing wilder in your winter bones.

Long Nights Moon

The Cold Moon rises on Thursday, Dec. 8. Also called the Long Nights Moon and the Moon Before Yule, this month’s full and luminous wonder will share the limelight with a bright and strikingly visible Mars. With the Red Planet at opposition (meaning the Earth is positioned between it and the sun), Mars will appear brighter than all the stars. Speaking of lustrous marvels, the Geminids meteor shower will peak on Dec. 13 and 14, illuminating the night sky with up to 120 meteors per hour. As its name suggests, this celestial pageant will emanate from the constellation Gemini, but here’s a hint: Just look up. The final meteor shower of 2022 happens in tandem with the winter solstice on Dec. 21 — the longest night of the year. Although it’s hardly as eventful as the aforementioned Geminids, a dark sky makes conditions favorable for the Ursids, a minor shower that peaks with up to 10 meteors per hour. May your nights be merry and bright. And your New

Year, full of light.

Someone I loved once gave me a box full of darkness. It took me years to understand that this too, was a gift. — Mary Oliver

Where the Sunchokes Shine

’Tis the season for Jerusalem artichokes, which are not, in fact, from The Holy City. Nor are they artichokes. These tasty tubers, also known as sunroots, sunchokes, wild sunflowers and earth apples, were first cultivated by indigenous peoples. When Italian settlers discovered this yellow-flowering plant, they dubbed it girasole, the Italian word for sunflower. The blossoms do look a bit like sunflowers, but they are actually more like daisies. Anyway, “girasole” became “Jerusalem” over time. You know how it goes.

Assuming the ground isn’t frozen, the tubers can be harvested all winter. Then what?

Scrub them, slice them and toss them with oil and spices.

Roast them until tender. Sauté them with garlic. Pan-fry them with butter and sage. You’ll figure it out.

A root by any other name would taste as savory and sweet. PS