12 minute read

The Legend of Eddie Pearce

How the “Next Nicklaus” found

new life on the rocky road to the Sandhills

Advertisement

B y B ill Field

A

s things go in dating, once things have gotten serious, you meet the parents.

The first time Linette Smith visited the Florida home of Doris and Wes Pearce, she was struck by the contents of one particular room with a bunch of tro

phies. Linette knew her boyfriend, Eddie, as a car dealer

at Larry Rigby Chevrolet in Abilene, Texas, who had sold her a new 1986 Camaro Berlinetta.

“Were you good at something?” Linette asked Eddie upon seeing the shelves full of silver curated by Eddie’s mother.

“Oh, yeah,” Doris interjected, “he was a golfer.”

In fact, Doris’ younger son was a very, very good golfer who before he had a driver’s license was being viewed as someone who not only could Gary Koch, a six-time tour winner and longtime television broadcaster,

recalls a 1969 high school match in which he and Pearce, his fellow King

High School star in Temple Terrace, Florida, were grouped with the No. 1 and 2 golfers of another team. It was a water-guarded par-5 that called for a

drive, layup and third shot onto the green. But not if you had Pearce’s talent and strength.

“The three of us had layed up, and Eddie takes out his 1-iron, which he was so good with, and powers it up in the air, over a lake and onto the green,” Koch says. “I glanced over at the other two guys and they’re shaking their heads like, ‘Are you kidding?’ I would still put Eddie among the top 10 ball-strikers I’ve ever seen — and that’s when he was 18 or 19 years old.”

Pearce is 68 now, nearly a half-century removed from winning the 1971 North and South Amateur at Pinehurst No. 2, another rung on his ladder to the greatness so many predicted.

He has been back in the Sandhills since late 2018 as general manager of

all the stories. “I make sure I meet as many people as I can when they come in because I know 95 percent of them play golf,” Pearce says. “They don’t know if I play or not. So, I’ll sit down with them and introduce myself to

them and they say, ‘Oh, I remember you.’ It’s amazing how many people do remember me.”

Pearce has been a success in the car business for almost 40 years, closing sales instead of closing out tournaments, which never became a habit once he turned pro and grew too familiar with closing time.

“It was probably 8-to-5 that I was going to make it to 35,” Pearce says. “Now I’m 68. Man, it’s been unbelievable. What a ride.”

He played 195 PGA Tour events, most from 1974 through 1981, although he made an improbable return for an additional season in 1993. The player who turned heads as an amateur never

won on the biggest stage, earning four runner-up finishes among just a dozen top-10s.

Pearce’s golf journey began in the Tampa area when he was just a toddler. Babe Zaharias, who owned Forest Hills Country Club with her husband, George, put a club in Eddie’s hands when he was 3. “It’s all I did,” he says. “It’s all I wanted to do.”

He was carrying a money

clip and wearing alligator-skin golf shoes by the time he was 16, a success in money games with the grown-ups in Tampa and in formal competition with his peers. He won the 1968 U.S. Junior Amateur at The Country Club in Brookline, Massachusetts — dispatching a handful of golfers who would become Tour standouts. “I knew I

would win when I stepped on the first tee,” Pearce told his hometown newspaper that

week. “I was brimming with confidence.”

Prior to claiming that national crown, Pearce was a dominant force for

years at the Press Thornton Future Masters, a premier junior tournament

in Dothan, Alabama, winning seven consecutive age-group titles between 1963-1969.

If Wes was in Eddie’s gallery, as he usually was, there was always a firsttee ritual. “I’d say to Dad, empty your pockets, because he always carried about three dollars worth of change in his pockets and he would jingle it,” Pearce says. “I’d put it in my golf bag and give it back to him after the round.”

Longtime Southern Pines resident Mike Fields, who played a lot of jutalked about how far he hit the ball and that the ball sounded different coming off his clubs. I remember he was also very friendly to the younger kids who idolized him.”

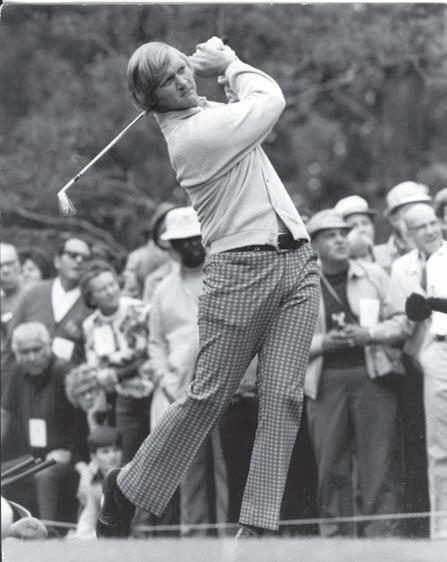

Pearce’s contemporary, Ben Crenshaw, a member of the World Golf Hall of Fame, told GolfChannel.com in 2013, “I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone with as much talent as him. Eddie had such a gorgeous, powerful swing. He could just hit the most beautiful shots you’ve ever seen.”

In his formative years, many of those shots were hit with plenty of cold, hard cash on the line. As a teenager, Pearce fell into a group of gambling golfers at Bardmoor Country Club in Largo, Fla. “There were money games with guys he perhaps shouldn’t be playing with,” says Koch. “But Eddie was always comfortable in those situations, almost weirdly so. He wasn’t too worried because he knew he was better from the standpoint of physical talent. Those guys would bet on anything — it was an interesting cast of characters.”

One of the regulars was

Martin “The Fat Man”

Stanovich. Once, after a week of thousand-dollar Nassaus, Pearce had won nearly $25,000 from Stanovich. Not long after that, Pearce was in a practice bunker working on

his superb sand game. He had been warned to leave good enough alone when it came to further bets with Stanovich, but didn’t listen.

“Marty was watching me hit those sand shots,” Pearce recalls, “and he said, ‘Damn, you’re pretty good.’ I said, ‘Yeah, I am.’ He said, ‘Well, you want to hit some shots, $100 for closest to the hole?’”

The wagers grew. After 90 minutes, Pearce had lost $20,000 to The Fat

Man. “I walk up to the clubhouse and I’m in a daze,” Pearce says. “Lloyd

(Ferrentino, who ran the course) said, ‘He got you, didn’t he?’ Marty was a

magician out of the sand. That was a hard, hard lesson. I know I had to play a lot of golf to get that money back.”

In the spring of 1969, Pearce, Koch and their King High teammates won the Florida state championship with a four-man, 36-hole total of 579. It remained a Sunshine State record for 30 years. Pearce was heavily recruited and went to golf powerhouse Wake Forest, where he stayed for two years before deciding to turn professional.

Sports Illustrated had referred to Pearce as the “Next Nicklaus.” With a powerful lower body and effective leg action, Pearce resembled the Golden Bear. “It was the time of the 1-iron and Eddie could really hit the long

Eddie’s personality was more King than Bear, outgoing like Arnold August 1986 when Linette Smith came in to buy a Camaro. “His closer

Palmer, the man who had convinced him to go to Wake Forest. Pearce was having a little bit of a difficult time with me,” Linette says. “So Eddie

never met a stranger, and his outgoing nature made late nights happen decided to come in and close the deal.”

all too easily. Pearce was runner-up in his fourth tournament of 1974, the Linette got her Camaro and, in time, a boyfriend. “We were really,

Hawaiian Open, but was never really able to build on that early promise. really good friends for about 3 1/2 months — we didn’t really date, we just

He safely kept his exempt status as a rookie, finishing 44th on the money hung out,” Linette says. “And then we went down for a weekend in Mexico

list, but only improved to 39th in 1975. and the rest is history.”

Detailed statistics for that era aren’t available like they are now, but Pearce still enjoyed the bar scene, but that wasn’t Linette’s. “After I came

Pearce’s putting, particularly once he became a pro, didn’t match his longinto the picture, he settled down,” she says. Pearce curtailed his drinking,

game skills. “Back in high school we used to joke that if I could ever hit it imbibing only occasionally these days. The couple got married in 1990.

like he did and he could putt like me, nobody would ever beat either of us,” “Third time’s the charm for both of us,” Pearce says. “She’s put up with me

says Koch, who was known as an excellent putter. for 30 years, and it’s been an amazing trip, a lot of fun.”

Pearce loved life on the road — too much — and didn’t have the selfLinette played an encouraging role in Pearce’s return to competition

discipline to practice more and party less. “A in the early 1990s. Inspired by

lot of guys talked to him,” says Roger Maltbie, a watching Hale Irwin win the 1990

friend of Pearce’s in their tour days in the 1970s,

“but Eddie was going to do what Eddie was going to do.”

An instinctive, natural golfer from childhood, as his career stalled in the late-1970s and early 1980s, Pearce got bogged down with mechan

U.S. Open at age 45, Pearce set

about getting fit, losing more than

50 pounds. He failed at Qualifying School in late 1991, but a year later, at The Woodlands outside Houston, 40 years old and wield

ics. “I had always had a good swing and played by feel,” he says. “I never thought about my

swing until the last few years on tour. And then I thought about it all the time when I was over the ball. The more I thought about it, the worse I got.”

In 1981, when he was only 29 years old, Pearce finished 210th on the money list after

ing a long putter, he got his card.

The bittersweet part was that his

father had died of lung cancer nine months earlier.

He savored practice rounds with

buddies he hadn’t played with in

a long time. But Dewars was now just the name of his dog, not his

being 225th the previous year, failing to earn as much in a season as he had in a week of money games as a teenager. He had neither a winning

What a ride.”

drink of choice. Though Pearce applied himself in ways that he

hadn’t the first go-round on tour,

lifestyle nor golf game. “By that point he was

struggling personally and professionally,” Koch

says. “Some of us were worried about him. Was

he going to be able to get his life squared away? What was he going to do?” Tired, frustrated and unhappy, Pearce packed it in after that lousy 1981 season, unsure what his future would hold. “When I quit playing, I gave everything away that had to do with golf,” he says. The inventory of

discarded equipment included two George Low Sportsman model putters Nicklaus had given him, clubs that a decade later were selling for thousands to collectors.

Pearce had an endorsement deal, doing commercials, for Don Reid Ford

in Orlando, and was good friends with Reid and his business partner,

Cesar Prado. (Prado is godfather to Eddie Pearce Jr.) They turned out to

be the gateway to his second career. “I asked Cesar, ‘What’s the deal with

this car-selling thing?’” Pearce says. “Cesar told me I probably would be real

good at it because of how I was with people, the way I took care of sponsors he couldn’t find the magic that had made him a can’t-miss kid.

He missed 19 cuts in 27 tourna

ments in 1993, shooting just six rounds in the 60s and failing to record a top-25 finish. He was unsuccessful at Q-School following the ’93 season and, a decade later, in trying to earn his way onto the senior tour.

“I’m very proud of Eddie and the way he dug into trying to make a

comeback,” Linette says. “It wasn’t for lack of trying that he didn’t do better when he got back out there. But perhaps Eddie wasn’t mentally prepared for all of it.”

Her husband was content to return to the car business, where he enjoys mentoring employees in whom he sees potential. One such young man worked in the detail department at Pearce’s previous dealership in Henderson but was interested in sales. He has moved up through the ranks and is now general manager of a dealership in Lee County.

“When you get somebody like that and they do well, it’s like it’s your

and guys playing in pro-ams.”

Prado was right. He got Pearce a job at a dealership in Lakeland, Florida,

that needed to improve its numbers. “That’s where he got his start, turning that store around,” says Prado, now retired in Texas. “Eddie is very personable, very likable and he had a knack for it. I’m just glad I was able to help a little bit and get him on a track where he could be successful.”

Over the next couple of decades, Pearce would put in three-month stints at dealerships across the country, becoming a specialist at organizing their operation and improving sales. “We’d take the store over, do all the training and all the advertising,” Pearce says. “If we turned it around, we’d come kid,” says Pearce, a father of two. “If I can latch onto a couple more folks

like that before my career is over, I’ll be happy. It makes me feel good to do that, because this business is a great business, it really is.”

Pearce has played little golf in recent years, although he and Linette

watch a lot of tournaments on television. “Eddie might reflect on a certain course that he played in the 1970s,” says Linette, “but we just enjoy the game. We enjoy watching the young players come up.”

It’s a different game than it was 50 years ago, but some golfers stand out as they always have, if not as much as Eddie Pearce did before he didn’t.