3 minute read

II. Lateran Obelisk 9

II. Lateran Obelisk, Rome

29-1/2”h., c. 1820. Fire gilded bronze on antique Egyptian Aswan granite base. By Wilhelm Hopfgarten & Ludwig Jollage. See Pricing

The very great majority of architectural models offered by Piraneseum, no matter how exquisitely rendered, were made as tourists’ souvenirs – evocative mementos of visits to the very most memorable places.

Occasionally though, a souvenir of a different, surpassing order comes our way. This extraordinary model of Rome’s Lateran Obelisk was cast and finished in the first part of the 19th century by two Prussian emigres to Rome, Wilhelm Hopfgarten and Ludwig Jollage – whose work came to be valued by popes, kings, and heads of state; leading sculptors like Bertel Thorvaldsen, (who employed the pair to cast their works, after failed attempts to lure them into their employ); and the very most wellheeled. Hopfgarten and Jollage’s production of architectural souvenirs (they cast gilded models of the Trajan and Antonine Columns; Marcus Aurelius Equestrian Monument; Arches of Constantine and, possibly, Septimius Severus; Capitoline Wolf, as well as the Flaminian and, as we see here, Lateran Obelisk was extensive; and supplanted the even more rarefied, often one-of-a-kind works made, until then, by Rome’s leading, storied decorative arts workshops, especially that operated by the Valadier family.

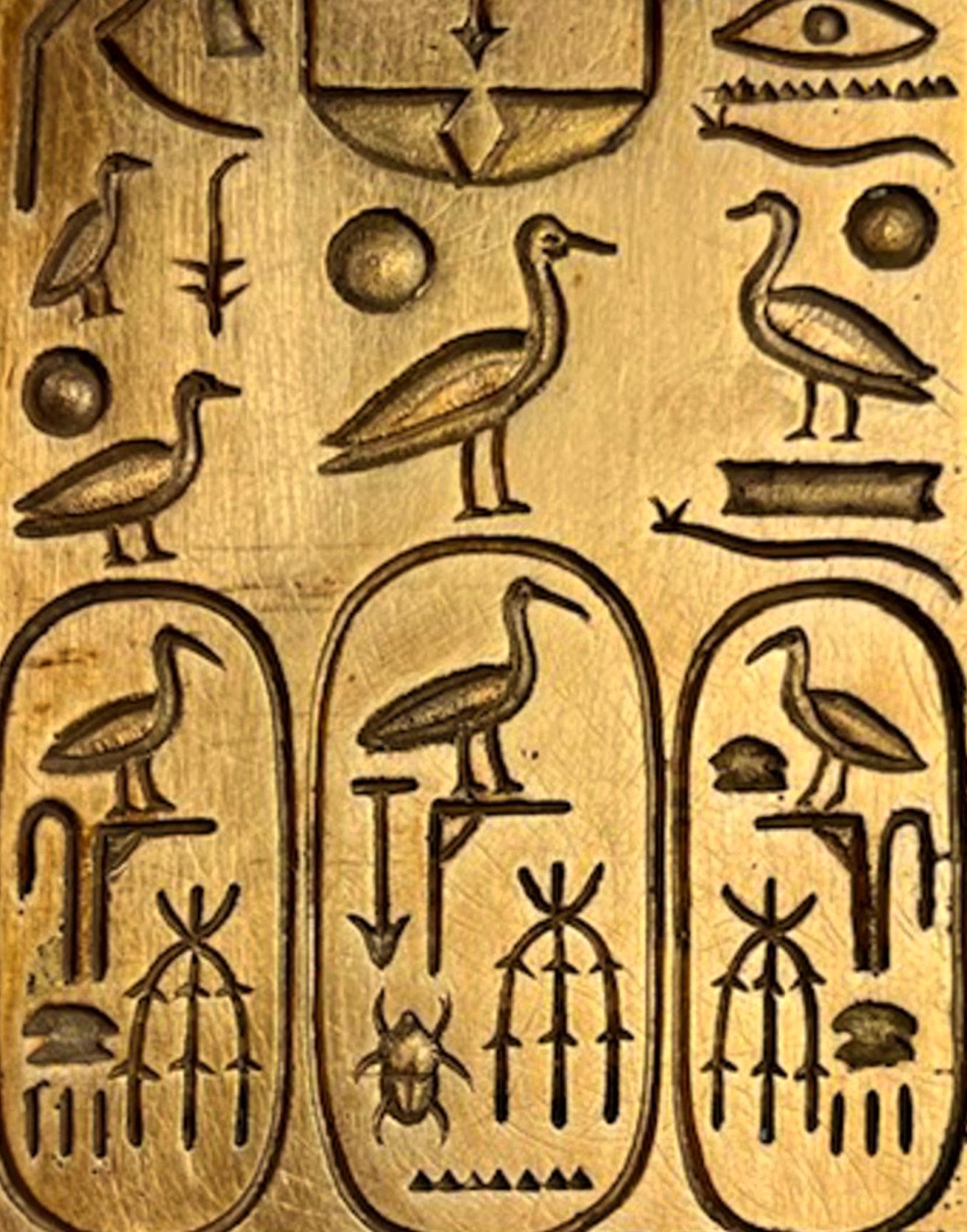

What is today called the Lateran Obelisk was originally erected in Karnak, c. 1400 BC, at the direction of a couple of Pharoahs Thutmose. Seventeen hundred years later (!), early in the 4th century AD, Roman Emperor Constantinus directed that the immense red Aswan granite monolith be floated down the Nile to Alexandria. By the middle of that century, the obelisk was on its way to Rome, where it was erected at the center of the Circus Maximus. Rome fell, and 1200 years later (!) in the 1580’s, Pope Sixtus V directed that the three broken pieces of the long ago toppled monument be excavated and re-assembled in the Piazza fronting the Cathedral of St. John the Lateran.

The bottom 12 feet of this obelisk were too damaged to re-use (in this way). Even without this, though, the monument remains the world’s largest standing Egyptian obelisk. That, of course, does not mean the discarded Aswan granite went to waste. Instead, it was employed, at least in part, as souvenirs, including the stone mount to the offered model.

Cast into the model’s base are Latin inscriptions, which do not reflect those inscribed when the obelisk was re-erected. Instead, these mirror the inscriptions chiseled into the base when it was originally brought to Rome, more than fifteen hundred years ago.

The Lateran is one of many ancient Egyptian obelisks in Rome, which is home to more of these monuments than Egypt.

Hopfgarten and Jollage’s Roman gilded architectural models are vanishingly scarce. We know of pairs of both their obelisks and their columns in Milan’s Pinacoteca Ambrosiana; and happened across another set of both their columns and obelisks in an out-of-the-way section of Rome’s Lateran Palace, the ancient part of the St. John the Lateran complex, close to the Lateran Obelisk itself. We asked if we might take a picture. The answer – “Non e possibile”. Last year, a pair of obelisks made six figures.

For more about the Prussians, an engaging 2016 volume – Hopfgarten and Jollage Rediscovered – Two Berlin Bronzists in Napoleonic and Restoration Rome, by Chiara Teolato, includes photographs of the firm’s gilded column and obelisk pairs, though not of the Marcus Aurelius and Capitoline Wolf models, not their Arches of Constantine or, possibly, Septimius Severus.