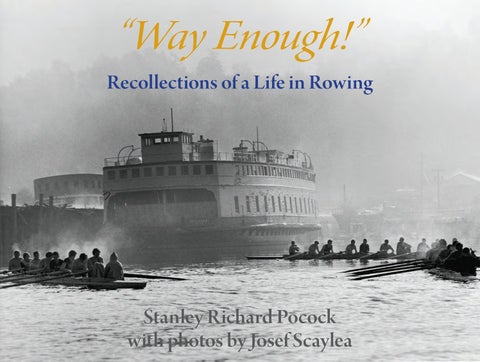

“Way Enough!” Recollections of a Life in Rowing

Stanley Richard Pocock with photos by Josef Scaylea

“Way Enough!” Recollections of a Life in Rowing

STANLEY RICHARD POCOCK

BLABLA Publishing - Seattle, Washington

Copyright © 2000 by Stanley R. Pocock Composition, design and artwork by Jim Ojala All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. All royalties from this book will go to the support of rowing. The author welcomes comments and suggestions from his readers. You may contact Stan Pocock by letter in care of Pocock Rowing Center 3320 Fuhrman Avenue East Seattle, WA 9802 U.S.A. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Applied For ISBN 0-65-206-4 Pocock, Stanley R. “Way Enough!” Recollections of a Life in Rowing Includes index. December 2005 Second Edition

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Dedication / Foreword / Apologia – i–ii

Early Days

Coach of the 50s

College

I – Shoving Off (1923-47) – 3–30

Crew Boy Engineer “Greetings” Ruptured Duck Poughkeepsie To Work at Last

II – Warming Up (1948-49) – 31–70

Frosh Job New Shop History of the Pocock Connection Learning the Game (Coaching and Boat-building)

Back to School

The “Conibear Stroke”

III – The Start (1950-52) – 71–92

–

Getting One’s Feet Wet Oakland Marietta Insanity Seattle Marietta Revisited Olympic Equipment Running (and NOT Running) the Shop

The New VBC

IV – Lengthen Out (1953-55) – 93–118

“Is That Your Varsity?” “What Happened, Al?” Learning to Coach at Last – British Empire Games They Don’t Shoot Horses I’m Out

Coaching by Mail

A “Sweep” ( Almost)

V – Lake Washington Rowing Club (1955-59) – 119–152 Syracuse

–

Seattle, Vancouver & Ballarat Gold LWRC is Born Victories Chicago More Victories

VI – Olympics (1960) – 153–184

Japanese Surprise

Small Boats Coach Summer in Seattle Technical Stuff More Technical Stuff Five in Finals Gold Sweep on the Schuykill Relocation

Prague Japan Success in Tokyo

São Paulo

Detroit

New York

–Worchester

VII – Second Wind (1961–64) – 185–204

Almost

Rome

–

Table of Contents

Allan Lobb

Syracuse

VIII – Thames River Idyll (1966) – 205–230

Lake Casitas

IX – Home Stretch (1967–75) – 231–258

Glass

London Oxford Lechlade Oxford, Again Windsor & Eton Turk’s Henley Revisited

First Home for LWRC

“Yeah, But…”

Munich

Lucy

Henley (the Third)

We Go Glass

–

––

X – “Twenty to Go!” (1976–84) – 259–288 Montreal Nottingham Henley Revisited (Again) Lucerne C Shells Eyes in the Boat Nonsense More Nonsense Stepping out Last Spasm XI – “Ten to Go!” (1987–92) – 289–314

Back for One More Try

Bled SYC & the MMs Austin Still Some Life in the Old Dog

XII – “Way Enough!” – 315–320 Glossary – 321–332 Index – 333–346 Josef Scaylea & Susan Parkman – 347–348 Index of Pictures & Illustrations – 349–360

Swetnam

Small Wonder

I

Dedication

T WAS A SERENDIPITOUS DAY THAT I CHANCED TO HAVE lunch with an old acquaintance, Jim Ojala, at Voula’s Off Shore Cafe across the street from my former shop on Lake Union. During our catching up on the five or so years of happenings since we had last seen each other, I mentioned in passing that I had just finished putting some of my stories into book form. I added that I had no particular idea of what to do with the memoir, other than to read it now and then for my own amusement and to someday pass it on to my children and grandchildren for theirs. Jim insisted that I let him read the manuscript. I met him later that week in the Steward’s enclosure at the 998 Windermere Cup and, in all innocence, handed over a copy. A few days later, he called excitedly to say, “This book has to be published!” Then he added the fateful words, “But it needs some work.” Those words led to nearly two years of often frustrating, sometimes maddening, ultimately rewarding effort, during which time I developed a new and healthy respect for the writing profession. Jim’s love of the written word has been an inspiration to me, and his artistic talent has been the means of creating what I now see as a work of art. To have been privileged — as I have been — to spend my years involved in the sport of rowing was a fortunate happenstance. Through it came into my life all those golden young men who put their faith and trust in me during my coaching days, and to whom I will be forever grateful. To have spent a lifetime creating with my own hands useful works of art in the company of hard working, talented artisans served as a leavening agent that helped me not only to overcome my disappointments out on the water, but also to achieve my successes. And, in my twilight years, to have met and married Suzanne has added a richness to my life that I never could have imagined. The joy of knowing and working with these people has illuminated my life and these pages. To them, and to Suzanne’s children and mine, this book is dedicated.

I

BEGAN WORKING ON THIS MEMOIR SOON AFTER RETIRING FROM SHELL-BUILDing some years ago. After I thought the book was finished, the serious work of seeing it mature into its present form really began. Many people contributed to the project. Among those who read the manuscript in its early stages, I would like to thank in particular Bruce Beall, Frank Cunningham, Duvall Hecht, Lyman Hull, Al Mackenzie, John Sack and Bill Tytus. Their encouragement kept me going. When I learned of Allan Lobb’s approaching death, I polished up the chapter telling of our sculling adventure down England’s River Thames in 1966 and brought it to him. Enthralled, he implored me to carry on and complete the rest. Among others who helped by contributing pictures are Sue Ayrault, Charlie McIntyre, Guy Harper, Roger Hansen, Susan Parkman and, especially, Josef Scaylea. Joe’s studies of the sport, unequaled and timeless, have helped immeasurable in making the written word come alive. As work on the book progressed, Joanne Ridley, Fred Nietzschke, June Lamson, John Stillings, Dave Peterson and Mischelle Day all read one draft of the book or another and offered valuable advice. When it came time to proof the final manuscript, Patricia Purvis stepped into the breach. Responsibility for any mistakes that remain rests entirely with me and the gremlins in my computer.

Introduction

Introduction Richard Erickson

I

T HAS BEEN SAID MANY TIMES THAT THE FIRST COACH IN YOUR given sport is — and always will be — your greatest influence. Stan Pocock was my first coach, as he was to hundreds of other University of Washington oarsmen in the 1940s and 1950s. In countless ways, he has had a great and positive influence on all of us old Husky oars, and on the sport of rowing in general. Stan’s memoir, “Way Enough!” completes the story of the Pocock family’s contribution to rowing, an unprecedented influence that stretched worldwide and covered the entire 20th century. Not enough people recognize that Stanley carried the torch for rowing and led the way for the sport to be where it is today. Most people think of Stan as a builder of gorgeous cedar racing shells. His accomplishments as a coach, an innovator and an advisor must not be ignored. After years of coaching the Lightweights and Frosh at Washington, Stan retired — he thought — from coaching to build shells full-time. However, in the fall of 958, he was approached by a group of graduate oarsmen from some ten colleges and universities around the country and asked to coach them through the 960 Olympic Games. At a meeting in Bagley Hall on the Washington campus — I was there — Stan addressed a score of candidates and introduced Harry Swetnam as his assistant. Stan’s message that day was, in effect “It has never been done before, but you can do it if you are the fittest and become more skilled than ever before.” Thus began the Lake Washington Rowing Club. Stan and Harry soon had us lifting weights — something unheard of in the sport of rowing in those days. We ran cross country and climbed Husky stadium stairs, we took nutritional supplements and trained in pairs and fours. Until then, we had thought we knew how to row; we quickly learned otherwise! A slew of national,

Pan Am and Olympic medals soon followed. In 960, crews coached by Stan filled every sweep-oared slot on the U.S. Olympic small boat squad and brought home a Gold and a Bronze from Rome. In Seattle, the Washington football, track and basketball coaches saw the success of Stan’s charges and adopted similar training techniques. Their results are a matter of record. This approach spread across the country in all sports, but it started with Stan and Harry in Bagley Hall in the Fall of 958. It was the beginning of training as rowers today know it. Stan’s father, George, was the expert on training for the traditional distance racing — gut-busting 2-, 3- and 4-milers. Stan developed the training methods for power and speed racing as the 2000 meter race became the standard in the 960s. Stanley, like his father before him, was constantly sought by other coaches to ride in their launches and offer advice. The result was better coaches and better crews, in an atmosphere that was always positive, never negative. In 977 my crews and I experienced all of this first hand, as Stanley — and his sidekick Harry — helped us turn a difficult season around and capture both the Grand Challenge Cup and the Visitor’s Cup at Henley, the first college crew to do so in twenty years. Of course, Stanley was above all a boat-builder par excellence. He learned from his father, but added to that legacy and built one of his own. As quality cedar and spruce became impossible to find, tastes for shells moved in the direction of composites. We all suffered when the sweet and sensuous smell of cedar dust in the shop was replaced by the sharp and acrid smells of resins and fibers. Pocock shells today — both cedar and composite — remain among the finest in the world, and crews are still winning races in wooden Pocock boats built half a century ago or more. Show me today a composite boat that someone will be able to say the same thing about in 2050.

Ulysses

…I am become a name For always roaming with a hungry heart Much have I seen and known… I am a part of all that I have met; Yet all experience is an arch, where thro’ Gleams that untravelled world, whose margin fades Forever and forever when I move. How dull it is to pause, to make an end, To rust unburnished, not to shine in use! …Come, my friends ’Tis not too late to seek a newer world. Push off, and sitting well in order smite The surrounding furrows; for my purpose holds To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths Of all the Western Stars, until I die… To strive, to seek, to find and not to yield.* —Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Ulysses In June 94 historian Frederick Jackson Turner delivered the Commencement address at the University of Washington. George and Dick Pocock — the author’s father and uncle — were already building boats on campus at the time, and Lucy Pocock, their sister, was coaching Washington women‘s crews. In his address, Turner quoted the above lines from Tennyson’s Ulysses and held them up as a credo for how his listeners ought to live their lives. In Tennyson’s poem, a grayed Ulysses, long-since returned from the Trojan Wars, calls upon his men to put aside questions of and age and infirmity and to set off in their boat one more time together in pursuit of new adventures. Tennyson’s words capture the ethos of the world into which Stan Pocock was born. *Quoted in Frederick Jackson Turner, “The West and American Ideals,” Washington Historical Quarterly V, 4 (Oct. 94): 25.

Apologia – i

Apologia

W

HICH FAMOUS FIGURE DECLARED THAT HISTORY IS more or less bunk? Henry Ford, I think. Old Henry might have been right. I read recently of a claim that few people ever tell the truth about the past. Not with the intent to deceive - though many of us have plenty to hide - but because we tend to reconstruct rather than remember. Not only are remembrances altered in the telling but, further, each retelling tends to bring new changes. If such be the case, it follows that if told often enough, a story purporting to be the unvarnished truth might have taken on a new life of its own. Varnished or unvarnished, what follows are some recollections - reconstructions, if you will - of my childhood, of my young manhood, of a lifetime spent around the shellhouse and in the shop and in the rowing game: what I remember as having happened. After completion of these reminiscences, the question arose, “What should I call this collection?” I recognized that my family and I had arrived at an important juncture regarding a rowing dynasty that had existed for many decades. Though the name was being carried on by the young man who had taken over, there was no longer a Pocock building racing shells. Nor was there anyone of our name racing in them or teaching others how. In bed one night, as I lay awake, it struck me: “Way Enough!” it would be! My father chose Ready All! as the title for his “memoirs” (he always used the plural and pronounced it “memoyers” as only an Englishman would - the way that it looks). Dad liked to say that he thought the interval when crews were poised and waiting to begin the race was the most exciting moment in rowing. His selection reflects the excitement of looking forward to life. The choice for my title has relevance as a companion to his in that it looks back on my - and his - contributions to the sport. For 30 years prior to his death in 976, he and I worked side-by-side in

the shop and spent countless hours together on the lake during my years of coaching college, club and Olympic crews. Our close association blessed me with the opportunity to absorb and respond to his ideas on rowing, on racing, and on the race which is the living of a life. To have my memoir resting on the bookshelf next to his, each title complementing the other, seemed fitting closure to a significant period in the history of American rowing. When he was writing his memoir, he told me that its title would be “No One Will Ask How Long It Took,” with the subtitle “They Will Only Ask Who Built It.” This was the advice given him at age 7 by his father when, as an apprentice, he was told to build his first single. In other words: take your time and do a good job of it. It was interesting that the first question often asked by anyone visiting our shop was “How long does it take to build one of these?” When such a question was directed at him in his later years, Dad invariably said, “Oh, about 65 years!” In short, one continues to learn. He used that first single to win the professional sculling race that earned him the money to emigrate to the New World. A journalist covering the race wrote “Young Pocock was undoubtedly aided by the excellent ship he utilised (sic).” An alternate choice of title contemplated briefly by me for these pages was “Don’t Flinch!” This was the only advice I remember receiving from Dad relative to personal behavior. I realized that he never intended it as a significant philosophic directive, but it did have some effect on my future behavior. The command “Way enough!” has been in use for centuries, possibly owing to British naval usage. Even today, the word “way” describes the movement of a boat or a ship. “Under way,” for example, means that a vessel has left its moorage. Thus, when the person in charge

Apologia – ii gives the command “Way enough!” he means that he thinks his vessel Triton “blowing on his wreath-ed horn.” Each could be identified by has gone far enough. I doubt that the term was much used around his signature cry, modified though it might be by elation or disgust. ships, other than to tell someone to stop whatever he might be doing. The invention of the battery-powered megaphone has lessened the I imagine that “Belay!” or “Belay that!” was used instead. More likely, romantic image I once held of coaches. No longer can intense emotion “Way enough!” was used in the cutters, gigs, wherries, liberty boats be expressed as in simpler days. Howling “Way enough!” in disgust or and other rowing craft that were employed to carry men and goods elation just doesn’t work today like it used to. All one hears are squeaks, from ship to ship and to and from shore. Often mistakenly spelled “w- squawks and earsplitting feedback. In some ways that may be a blessing, e-i-g-h” (that word has to do with lifting, for all too often what comes out would as in the phrase “to weigh anchor”), “w-abest be left unsaid. Pounding electronic y” is what it is. I might add that in some horns on the deck might still accomplish parts the commands “Easy all!” and the desired effect, but replacing the horns “Let ’er run!” are used instead, but never is expensive, and they can’t be hammered were by us. These sounded too much like back into shape and used over and over advice on how to row. In the context of again as could the megaphones of the the sport of rowing, the command simply past. means “Stop!” This memoir tells of my life, by “Way enough! ” is probably the turns as a child, as an oarsman, as a happiest phrase to be heard in rowing, coach, and as a builder of racing shells. often awaited with great anticipation While I am no longer any of these, by people who pull an oar. From the one must not infer from the title that coach’s point of view, it is also the I think of my life as having come to most effective of commands. I came an end. I prefer to think of the title as to believe that all I had to do was raise a command to pause. Typically, in a my megaphone and think the words rowing workout “Way enough!” gives and my crews would stop. I recall one Al Ulbrickson - circa 1953 one the chance to rest, think and listen old coach who, when asked why he to advice, abuse or encouragement. stayed so far away from his crews while out in his coaching launch, Refreshed, one can then approach his next effort with renewed answered that “the further away they are, the better they look!” vigor and enthusiasm. So it is with me. Knowing him, I’m sure his crews heard his “Way enoughs” no By the time someone wades through these many pages, those magic matter how far away they were. words “Way enough!” might be just as eagerly greeted as they are by I loved to listen to the special way various coaches gave the a coach’s exhausted charges. The reader might want to avoid reading command. Some used a long, drawn-out “WAAAAAYnuff!!” with a this volume as though it were a novel. What is presented here is a series falling inflection at the end, others, a short and assertive “wayNUFFF!” of stories in roughly chronological order, with an index that is detailed with rising inflection, still others a rumble that bespoke of the god enough to point the browser toward subjects of particular interest.

I – Shoving Off (1923–1947) – 3

CHAPTER I

I

Shoving Off (1923–1947)

GREW UP IN THE SHADOW OF A FAMOUS FATHER. THE SPECIAL place that the sport of rowing and, in particular, rowing at the University of Washington, held in the minds of the people of Seattle in those days assured him of public celebrity. Because of this exposure, and with his distinguished presence — to say nothing of his fine British accent — he was seen as a man of stature. This recognition gave weight to his words, and he exercised great influence upon the young men around the shellhouse and, far from incidentally, on many of those people — young and old — with whom he came in contact in the community. Self-educated, he read widely throughout his lifetime. He knew rowing well, having been a champion sculler in his youth. He was an artist, a craftsman, a thinker and could talk well on these disciplines. He had a wonderful philosophy for living and passed this on to the young men who attended his Sunday school classes. The young men who rowed would listen, as would the coaches. He was mentor to many people throughout his long years around the church and at the shellhouse. After I learned how to read, I hated my given name. I associated it with one of the characters in the cartoon “Toonerville Folk” featured in those days in The Seattle Daily Times. My nemesis was a character identified as the “Unspeakable Stanley ‘Stinky’ Davis, the boy who wets his pants.” I have no idea if others made the connection, but I surely did and fretted over it.

When still in kindergarten, I was forced to take part in a fashion show for the mothers at a PTA meeting which featured children’s clothing from Rhodes department store. I can still see the snazzy and expensive gray suit that I had to parade around in: short pants, vest, jacket and a nasty little cap to top it off. Disgusted with the whole affair, I expressed my viewpoint on the issue by wetting my pants in the middle of the show. While that drew a few laughs, I paid dearly; not only did my mother have to buy an outfit which she could ill afford, but I was stuck with the suit until I grew out of it. I dreamed of having a classier name — one such as Stanton or Stanford — but Stanley it was and so it would remain. Dad called me “Stanlo,” “Old Stocking” or “Old Sock” — names that I loved. Everyone settled on the name Stan, except my mother and sister. To them, I have always been Stanley, which is OK. If anyone addresses me by my full name now, I find it flattering and I like it. My sister Patty and I were not particularly healthy when we were small. Nothing serious, but we were plagued with colds. Perhaps this came from our having to sleep in a wide-open, unheated sleeping porch winter and summer. When illness struck, Mother never sought a doctor’s advice — it cost too much. How on earth either one of us survived the constant regimen of mustard plasters, cold compresses, cod liver oil, castor oil, ipecac, the dreaded “red bottle medicine” (enemas) and all the other home remedies prescribed by our grandmother and great-grandmother I’ll never know.

I – Shoving Off (1923–1947) – 4

“Toonerville Folk” cartoon featuring the “Uspeakable ‘Stinky’ Davis” Despite all, I had a happy childhood, at least around home. My earliest recollections are of a stern, reserved, preoccupied father — a fair man, yet one who brooked no nonsense. He had strong religious convictions and a keen social consciousness. I saw him as incorruptible. He never drank, although I did have a beer with him once in later years. Asked about his aversion to alcohol, he

said that while still a young boy he saw a drunk being thrown out of the pub next to the flat where he and his family lived on High Street in Eton. The man landed on his head and bled copiously. This incident, along with all the drunkenness he saw each day, made him resolve to stay away from the Demon Rum. I did not see him as being intolerant of those who used alcohol, only determined that none of it would be seen around our house. The sole exception I can remember was a case of beer that sat in our basement for years. It had been sent to Dad by the president of the West Side Rowing Club in Buffalo, New York in a wellmeant but inappropriate expression of appreciation for a boat he had built them. That box leered at me every time I went down to the basement. When the temptation grew too great, a friend and I began sneaking down now and then to share one. The bottles were packed in sawdust, and we buried the empty each time, figuring that no one would be the wiser. At dinner one evening, Mother mentioned that she had decided that day to throw the box out. On moving it, she thought it very light and dug into it, only to find all but one of the bottles empty! I thought it a good idea to play dumb. She said it must have been the painters. They had been there just the week before to redo the kitchen. I let it go at that. Interestingly enough, I developed no taste for beer out of that misbehavior and stayed away from it all my growing years. Dad almost never used strong language. “Dash it all,” “I’ll be jiggered” and “by Jove” covered his swearing, although I did hear a “hell” or two. I grew up in awe of him and his self-discipline: cold shower in the morning and all that. His calm public persona was all the more remarkable given that he suffered agony from chronic migraines. Patty and I were often admonished, “Be quiet! Daddy has a headache.” He worshipped the ground my mother walked on, and I never heard a harsh word exchanged between them. As I was to learn later, this atmosphere was hardly a realistic preparation for the realities of life to come. It did, however, assure me and Patty a pleasant childhood.

I – Shoving Off (1923–1947) – 5 Mother and I were the best of friends. Generally rather quiet and reserved, she gave free rein to her lively, playful spirit when Dad was away with the UW crews each June. When we were still quite young, Pat and I could take turns sleeping in her big bed. We could make noise around the house. I could play “last tag” with Mother before I went off to school. She wouldn’t give up and neither would I. Often the two of us ended up rolling on the floor with laughter. What fun we had! She would even take us out to dinner, despite the hard times. As we grew older we could stay up late, listening to the radio or talking endlessly. I don’t mean to imply by these comments that life was unpleasant around home when Dad was there. Quite the contrary. I can only remember being paddled by him twice, and both times I deserved punishment. The first time was when he discovered the sheets of Christmas Seals missing. After I confessed to having taken them to kindergarten to show my classmates, he said I deserved a spanking. I ran and hid under the kitchen table. When found, I suffered the consequences. I’m not sure which lesson I learned: never to take anything not belonging to me, or never to admit having done so. The other time was when I mouthed off at Mother in his presence. He would not tolerate that kind of behavior. I was proud of him, of what he did and of what he stood for. He earned the respect and love of the three of us in every way. By comparison, my childhood days outside the home and our immediate family were not quite so happy. I was unbearably shy and disliked school. I could never make my top spin the way all the other boys could and invariably lost my pocketful of marbles in the illicit playground games at recess. It was difficult for me to make friends, and I was much happier when by myself. As a first-grader I did have one friend — Phillip Craig. He and I had great fun walking around the neighborhood after school, shouting out all the naughty words we had ever heard. It almost broke my heart when, toward the end of the second grade, I learned that we were going to move away. Long afterward, I was told that the folks had wanted to leave the district because of some of the bad kids hanging around. Perhaps they were

Worried fathers, loyal wives, (mostly) happy children – circa 1927 The author’s family, with Uncle Jim, Aunt Lucy, cousins Betty and Grace right. Also, maybe some of the other parents were equally glad to see us go for the same reason. OUR MOVE PROVED A HAPPY ONE. LAURELHURST IN THOSE DAYS was a great place for a kid. Because the area was only about half built up, there was room aplenty for us to roam, build camps and tree houses and dig forts. I still found myself shy and friendships hard to make. Bob Cline was my closest friend. He moved away when we were freshmen at Roosevelt High School, and I heard nothing of him until my fiftieth high school reunion a year or two ago. There, I learned that he had died in a plane crash in Dallas some years before. Kenny Moritz was another good friend. He lived across the street, and we shared many happy times. Of a scientific bent in those days,

I – Shoving Off (1923–1947) – 6 Left: The Pocock family home at 3608 43rd Avenue Northeast, Seattle, Washington Below: An aerial view of Laurelhurst looking east — circa 1937

Lake Washington Laurelhurst Light Pocock Family Home

Wherry Float Union Bay

I – Shoving Off (1923–1947) – 7 we spent endless hours performing experiments involving the use, not only of chemicals and electricity, but also of such mundane materials as ink, salt and urine. I’m surprised that we didn’t end up killing ourselves. One of our friends, George Kreiger, managed to blow off a few of his fingers. Luckily, I was not involved in that episode. Kenny moved away, and I heard later that he became an English major and was for a time a professor at University of Southern California (USC). Others I enjoyed included Howard Angel, George Jackson, Bill Scott, Richie Strom and Frank Curtis. When the war broke out, Frank became the only conscientious objector in our crowd. He served time at McNeil Island and was one of the few prisoners who ever escaped, though only briefly. He succeeded in swimming to the mainland, where he was so exhausted that he fell asleep on the beach and was soon retaken. Frank, too, became a teacher — at Reed College in Portland.

Interior of old UW shellhouse – circa 1922

Although today Laurelhurst is known as an enclave for the wealthy, during the Great Depression, when we lived there, I never knew any kid whose parents were rich, with the possible exception of one whose mother had her own car. The rest of the families struggled. THOSE WERE TOUGH TIMES, WITH LITTLE MONEY AROUND. PAT and I received no allowances; what little spending money we had came from picking wild blackberries in season (ten cents a quart), from mowing lawns (two bits) and from collecting pop bottles (three cents apiece courtesy of Ben’s Drugstore). If we were lucky enough to find a quart-sized ginger ale bottle, Ben gave us a nickel for that. A neighbor kid, Billy Brugman, was an ambitious sort and had several lawns to mow. One summer, he managed to save up 14 dollars! When I grew older, I took over the job of mowing our lawn from Mr. Nelson after he mysteriously disappeared. His body was later discovered far out in the country where he had wandered off, only to die of natural causes. Dad gave me a whole dollar a week for doing the job. Billy, of course, was jealous, but I made sure that I earned every nickel of my pay by manicuring the place to within an inch of its life. I remember one day spending a full eight hours before I was satisfied with the job I had done. My cousin Betty was getting married, and the bridal dinner was to be at our house, so the yard had to look good. Although we were better off than many, those must have been worrisome times for the folks. Years later, Dad told me that he had had no savings, but was fortunate in that his monthly income never fell below 00 dollars. With this amount, he was just able to keep up the payments on the house and provide us with food. He found jobs for the few men who were working for him when the Depression hit. With no rent to pay (he was given use of the space for his shop in the UW shellhouse in return for taking care of the rowing equipment), he survived by making and supplying spare parts and oars. For more than two years, there were no orders for boats. One morning, he went to pick up the mail at University Station up on the “Ave” (University Way). There, out of the blue, was an order from Columbia University.

I – Shoving Off (1923–1947) – 8 Flush with back-to-back Intercollegiate Rowing Association (IRA) victories under their belt, they wanted two eights and two sets of oars. One can easily imagine the sense of relief he felt when he opened and read that letter. On Saturday mornings Dad often took me with him on his shopping rounds. One regular stop was at the Japanese truck gardens below the UW campus where University Village Shopping Center now flourishes. We would take an old-fashioned shopping bag with us and with one dollar buy all the vegetables we could cram in. That kept our family going for a week. In the madness of World War II, the Japanese farmers were forced to leave, and never came back. We assumed that they owned the land and were gypped out of it by those who took advantage of people in their situation. We learned later that they had only been renters. Most interesting to me on those Saturday excursions were our visits to the supply houses, lumber yards, ship chandlers and paint stores where Dad would lay in supplies for his work. I loved the great piles of lumber at Ehrlich-Harrison, the evocative smells of cordage and tar at Seattle Marine Supply, the incredible catalogue at Seattle Hardware Company that I used to read as though it were the Bible, and the marble splendor and solemnity of University National Bank with its mysterious safety deposit vault in the basement. Invariably, we finished at “the shop,” which is what we always called the place where Dad built his boats. I loved to go there most of all. Occupying the back part of the old UW shellhouse, it was a modest layout. The smells were so wonderful. Each of the various woods had its distinctive odor, but Western red cedar, Alaskan yellow cedar and sugar pine were the best. Years before I had the chance to work in the shop, I sensed that was where I belonged. Some Saturdays we made it to the shellhouse early enough to go out in the coaching launch with Al Ulbrickson, the Varsity coach, and watch a turnout of the UW crews. Those rides, so glamorous and exciting, were special for me. The names of those heroes stick with me even today: Ed Argersinger, Hank Schmidt, Herb Mjorud, Curly Harris, Herb Day, Stan Valentine, Polly Parrot, Carl Reese, Dick

Odell and Harvey Love. They were larger than life to me. I wondered if I could ever hope to be their equal when I grew up. Always welcome in the launch, Dad often went out to watch the evening workouts during the week. I remember sitting at dinner in the kitchen on more than one occasion when the back door would open just enough for his hat to come sailing in as he tested the domestic waters after a late outing. At the age when one must make such decisions, I decided to cast my lot with Dad and spend my life as a builder of racing shells. I couldn’t imagine the boats not being built once he was gone, and I wanted to carry on that tradition.

UW Varsity – 1933 – left to right: Bob White, Wil Washburn, Herb Mjorud, Herb Day, Gordon Parrot, Bob Snider, Walt Raney, Ed Argensinger, Harvey Love Later, right out of college, I went to work at the shop. As time went on, he and I became the best of friends, working closely together until he died at the age of 85. I never lost my great admiration of him. Until the day he passed away, I saw him as a prince among men, as I still do.

I – Shoving Off (1923–1947) – 9

7

2

11 9

4

3 5

1 3

8 6 10

Aerial view looking west toward Union Bay, the University of Washington, & Portage Bay – circa 1947 – () – Old shellhouse; (2) – Montlake Cut; (3) – Future site of Conibear shellhouse; (4) – Future site of George Pocock Memorial Rowing Center; (5) – Truck farms (present-day site of University Village); (6) – Student housing, first home of Stan & Lois Pocock; (7) – Portage Bay & the sailing ship Fantome; (8) – Union Bay; (9) – University of Washington; (0) – Victory gardens; () – Future Lake Union site of “the shop”

I – Shoving Off (1923–1947) – 10 ANOTHER CHILDHOOD STORY I CANNOT RESIST RELATING IS of the time in July of my seventh year when Dad took me and my cousin Frankie on a camping trip down Hood Canal. We made the two-week adventure in a nice lapstrake dingy that he owned. The name Takenite carved on its transom identified it as having originally belonged on a yacht of the same name owned by Mr. Boeing of aircraft fame. While working at the Boeing plant, Dad and his brother Dick in their spare time had built a similar boat in the basement of the modest house they shared. It was such a beauty that Boeing had to have it. He offered to trade boats. When the boss says he wants to trade something, what do you do? You trade. Originally, it had sported a little one-lunger engine, but that was now replaced by a big Evinrude outboard of early vintage. We loaded everything needed for our two-week adventure and took off from the old shellhouse early one foggy Saturday morning. The night before, Dad had told me to be sure to bring along my Boy Scout whistle, of which I was very proud. He thought it might come in handy should there be fog out on Puget Sound. In one ear and out the other. The next morning we headed out through the Ballard Locks and ran straight into a dense bank of fog covering the Sound. About halfway across, we heard a big ship approaching. It had to be one of the Princess boats charging down from Canada. As the sound drew nearer, Dad called out, “You better start blowing your whistle, Stanley.” “I forgot it, Daddy,” I cried back, wondering to myself what-onearth good would that do. Just then, the ship hove into view, awesome in its majesty as it towered over us. I could almost reach out and touch it as it tore by. Hard as it tried, its frightening wake failed to swamp us. Had the ship hit us, no one aboard would ever have been aware of it. Despite that hair-raising beginning, the trip was a happy one. For the next two weeks, we lived off fish and clams, swam and hiked during the days and camped on the beach at night. A big boy now, I was allowed to have coffee (heavily laced with condensed milk). I

didn’t like it, but pretended that I did. That trip remains one of my happiest childhood memories.

I ENTERED THE UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON SCHOOL OF Engineering in the Fall of 1942 with a civil engineering (CE) degree in mind. Why CE? Math and the sciences came easily to me, and I enjoyed building things, so I guess it was a logical enough choice. The decision was made easier when I learned that CE was the only engineering degree that did not require my writing a thesis. Once in school, it seemed only natural that I turn out for rowing. That was why I was there in the first place. For an education, there were other places to go, but not for rowing. To me, crew and the University of Washington were synonymous. The Husky oarsmen of the past were my heroes, and I longed to become one of them. I took no part in athletics at Roosevelt High School, having been too busy studying and too bashful to find out how to try out for any of the various sports. What’s more, I was so awkward. Tending to be left-handed, I never knew which hand to use when throwing or batting a ball. Although I enjoyed soccer while in grade school, there was nowhere to go with that sport in those days once one advanced on into high school. I also enjoyed the rough-and-tumble of the informal football games up at the Laurelhurst Playfield. Rightly or wrongly, I was warned away from turning out for football by Roy Armstrong, director of playfield activities. I did know something about sculling. Dad had given me a wherry (a relatively stable sculling boat) when I was 12 or 13. Secured to a little cart, it could be wheeled down to Lake Washington only a couple of blocks from our house. One evening, Bruggy and his father went with us and helped paddle an old float across Union Bay. Formerly used by the UW crews, the float had been abandoned and left to rot in the tules. Mooring the disreputable old relic at the street-

I – Shoving Off (1923–1947) – 11 end near our place brought a few muted squawks from neighbors. It made a great place to launch from, however, and, as time went on, I found more than one of the squawkers putting it to their own use. Dad never gave me any particular instructions on how to scull. I think this stemmed from his belief that sculling should come naturally or not at all. He told me of the first time, at age , that he was put out in a rumtum on the Thames River in England, and of how excited my grandfather had been to see the natural way he had taken to it. My first paddle was relatively uneventful, eliciting no noticeable excitement on Dad’s part. In the past, I had occasionally watched him scull; now I was left to figure it out on my own A big trip for me was to row around Laurelhurst Light and up to the Beach Club where there were girls to watch. I always let friends who were interested take the boat out, and two or three of them later turned out for rowing at the university. Jane Eddy was the only girl who ever used it, and she became quite good. Unfortunately, there was no rowing program for women offered around Seattle then. Down at the shellhouse one day, after I had put in enough miles to build up my confidence, Dad let me go out in his single. (If you want to raise my hackles, just call a single a “scull.” Know that a sculling oar is a scull, and a single sculling boat is a single.) I could not believe how unstable it was. Paddling along, I wondered how anyone could ever pull hard enough to work up a sweat. Suddenly, I tumbled headover-teakettle into the drink without the slightest idea of what I had done to cause the mishap. Luckily, the boat was not damaged, and I was close to shore. Despite the embarrassment of that first disastrous outing, I didn’t give up and soon could handle a single quite well. I didn’t fall out too often and certainly found I could pull hard enough for a good workout. The thought of racing in my single never entered my mind, there being no sculling competition around at the time. Sculling races took place on the East Coast, but who ever heard of traveling that far to suffer pain? Phil Lewis and his wife kept wherries at their houseboat on Portage Bay, and Bob Lamson had an ancient old single, but he

lived clear down at the other end of Lake Washington. These few souls (rarely seen on the water), plus Dad and me, made up the entire field. What we should have done was put a couple of wherries at the Beach Club and organized a sculling program there. I’m sure it would have gone over in a big way.

Gus Eriksen & George Pocock – 1949 I A LMOST FORGOT: THER E W ER E T WO W HER R IES AT THE shellhouse that Dad let UW oarsmen take out. The most use ever made of them came one spring after Gus Eriksen was kicked off the Varsity squad for fighting. Refusing to give up, he rowed a wherry wherever the Varsity went. After a few weeks of this, Dad raced him in from Laurelhurst Light one night. Gus acquitted himself so well that Dad passed the word on to Ulbrickson. Al relented and let him rejoin the Husky squad.

I – Shoving Off (1923–1947) – 12 Eriksen wound up stroking the JV to victory at Poughkeepsie, thus earning his third Varsity letter (Big W). (As an added incentive, JV crews in those days were promised Big Ws should they win at Poughkeepsie. Members of the Varsity received theirs, win or lose.) Gus’s rowing experience was unique. There was no requirement dictating normal progression toward a degree in those Depression years, and Gus struggled while working his way through school. He became the only person who was ever awarded an Honor W for having rowed four years without winning a letter and then went on for three more years to win Big Dubs. Gus was also the only man ever to turn out for swimming, skiing and rowing at the same time. Had Al known, he would have kicked him out for that, too. Another Gus story. He was always late for turnout, and his crew would cover for him by taking their eight out and putting it on the water while he dressed. One winter afternoon, Gus came racing out, oar in hand, only to slip on the ice-covered ramp. Skier that he was, he confidently schussed down toward the shell. Reaching water’s edge, he tried to regain his balance by planting his oar on what he hoped would be the float. It wasn’t; it was the bottom of the boat. Al had already headed out with the other crews, not being one to wait around for delays. The crew took the waterlogged shell back in and brought out a substitute. After the workout, Gus confessed his sin to Dad, who the next day quietly went about fixing the boat, Al none the wiser.

out by Fox Point and found ourselves flat on our backs. The concrete blocks dropped through the bottom of the boat, and down we went. I made the great mistake of laughing. That was the only occasion, save one, when the two of us ever rowed together. Years later we went out in a quad sculler with two of the McIntyre brothers. That outing did not go much better. The three of them were sculling left-hand-over-right while I, by habit, was doing the opposite: right-over-left. (Dad always said that only amateurs sculled right-over-left.) He was at stroke and started off as though we were racing at Henley. What a mess!

Old Nero with Frosh coach Bud Raney standing in mid-craft – circa 1940

THE FIRST TIME I HAD A SWEEP OAR IN MY HAND WAS IN A COXED wherry pair with Dad when I was still in high school. There being no coxswain handy, we put some chunks of concrete in the stern to make the boat trim right. We shoved off with me at stroke and him in the bow where he could watch what I was doing and, presumably, where we were going. Things went badly. Finally, Dad hollered, “Come on, let’s go. I’m only pulling with one hand!” “Well,” I replied, “I don’t have the faintest idea what I’m supposed to be doing!” At that instant, we ran head-on into the navigation buoy

BACK TO MY FRESHMAN YEAR AT THE UW. THERE WAS NO ONE else in the turnout who had ever had an oar or scull in his hand. I had a hard time keeping my mouth shut, but figured it was a good idea. On the one hand, I was sure I could have helped; on the other, I was sure my help would be ill received. Besides, I was having troubles of my own. Once we graduated from Old Nero into the shells, I began to catch crabs (see Glossary). I couldn’t figure out for the life of me what the problem was. Much later, when I was back at the UW after a stint at Navy Boot Camp, I discovered the cause.

I – Shoving Off (1923–1947) – 13 In those days, we each jealously used our own oar. I searched through the racks and came across the oar I had used as a freshman. By then I knew enough to check the pitch. Sure enough, it should have been a starboard oar, although it was marked port. (Oars from our shop were intended to be absolutely true, and, while most of them remained neutral and could be used on either side, inevitably some took a slight twist. Except for the rare one now and then, they could still be used on either side, but to make sure that they could be used properly, we checked them closely and marked them either port or starboard.) A shim under the leather of my oar was causing the trouble. Someone in the shop must have thought it needed a little help. Once in use, the oar straightened out. I don’t know how I ever managed to row with it that way. In my ignorance, I stuck with it and struggled. The coach offered no help, no doubt thinking that I should know how to handle whatever was going on. Once I removed the shim, the oar worked fine, and I had no more trouble with it. Besides rowing, I began my college education in freshman engineering and was introduced to fraternity life on the campus. The engineering part came easily. I had an adequate academic background gained at Roosevelt High School where a large percentage of the students planned to go on to college, and the atmosphere for learning was favorable. As for joining a fraternity, I had never planned on it. I was at the UW Bookstore buying books one day before classes started when I ran into Johnny Dresslar, a friend from Laurelhurst Grade School who had graduated a year or two ahead of me. He asked whether I was going through rushing. I told him I was not. Urging me to do so, he promised an invitation for me to come visit his house, Phi Gamma Delta, if I signed up. I went down to the InterFraternity Council office, put my name on the list and soon received the promised invitation. On my first visit to the Phi Gamma Delta (Fiji) house, I was interested to find that many of its members were oarsmen. On my second visit I made points by asking some of the upperclassmen if they would like to sneak into the shellhouse and take out an eight. They wanted to, we did, and the adventure scored

Author, second from right, at Roosevelt High School – 1941 me points. Other rushees must have found the Fijis’ interest in rowing attractive, for when Rush Week was over, there were nine men in my pledge class who went out for crew. That there were many Roosevelt grads on the list of pledges did not excite me. They were all big shots — star athletes and politicos with whom I had had little or no contact. There were two or three whom I knew slightly and grew to like. I received invitations to visit several other houses: the SAEs, Sigma Chis and Alpha Delts, among others. I was especially drawn to the Alpha Delts. Aside from having several oarsmen in the house, they seemed to be a decent bunch. The only trouble was, I knew that one of their members was seriously interested in the girl I was dating. I figured that might cause trouble, so I wrote off the Alpha Delts. Not long after that, she gave me the gate, and they later married. Another reason I found the Fijis attractive was that they did not allow drinking in the house or at their parties. I was straight arrow in those days, and this seemed important. Many of them drank, of course,

I – Shoving Off (1923–1947) – 14

Bob Ellis – 1944 as I soon found out, but they did it elsewhere. Whatever my reasoning, I decided to pledge Fiji if they buzzed me, which they did. There were some of the men in the house with whom I became close friends, and I have never regretted that decision. Through the associations established there, I became acquainted with a wide spectrum of men with interests far beyond rowing and engineering. I came to appreciate the very active Fiji alumni group. Older men, they took a vital interest in us youngsters. They wanted to get to know us, to hear what we were doing and to help us wherever they could. I saw them as men of the real world who had much to offer a young man.

NOT LONG AFTER CLASSES STARTED THAT FALL, WE ALL WENT over to Eastern Washington to pick apples. The war being on, apple knockers were scarce, and much of the crop was in danger of being lost. The university shut down classes for several days so that students who wished to do so could go over and pitch in. A special train took us to Wenatchee, where we were assigned to the various ranches in the area. I landed somewhere in the boondocks with Bob Ellis and two coeds. Bob was a pledge brother and a good friend. Tragically, two years later he lost his life in the Battle of the Bulge. His two brothers, Jim and John Ellis, became household names on the Seattle scene for their involvement in projects ranging from Forward Thrust and Metro to the World’s Fair and the Seattle Mariners. I have often wondered what Bob would have done with his life had he lived. A fine young man, that he would have made his mark is without question. Bob and I imagined many exciting possibilities at the sight of our two female companions. These hopes were dashed when the girls announced that they were seniors, which meant they were beyond our reach. They need not have worried, anyway, because the rancher’s wife was a demon chaperone. She, too, had lurid ideas of the goings-on among the big city college kids and there would be none of that on her farm. She watched us like a hawk. There was one benefit, though: she was a great cook — as long as you liked overcooked vegetables, meat and potatoes. With no wartime rationing in effect on the farm, we had all the bacon, butter, eggs and meat we could stuff in. We worked about 2 hours a day picking and, except for eating, slept the rest of the time. Also working at the ranch were two dissolute characters who made their living at fruit-picking. They laughed at the warnings we were given about not picking up fruit from the ground and about handling each apple very carefully. They advised us that we would never make any real money that way, and they were right: We followed directions and did not make much. To top it off, back in Seattle we had to listen to all the wild stories about what supposedly went on at the other ranches.

I – Shoving Off (1923–1947) – 15 The reason for such a huge class was simple: young men were being drafted or were volunteering for the armed forces in great numbers. Because they were suffering such a high rate of attrition, fraternities needed to inflate their ranks to start with if they were to continue paying their bills. This problem was solved for them some months later when the federal government established the V2 Naval Officers College Training Program. Many colleges and universities throughout the country engaged in this part of the war effort. With the program in place at the UW, all the fraternity houses were leased to serve as dormitories for candidates seeking Navy or Marine Corps commissions. There were similar programs for the Army and the Army Air Corps. The idea was to provide a continuing supply of college-trained officers for what might be a long war. Lightweight crews – 1948 I FINISHED FALL QUARTER IN THE SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING with good grades and looked forward to the new year. Forever gullible, I had been led to believe that the Fijis did not subject their pledges to Hell Week as a preliminary to initiation. Not true. The first week of Winter Quarter before classes began was devoted to that insanity. The monkey business mostly entailed loss of sleep, and this did not contribute much toward making a good beginning on the new quarter. Still, I must say that, compared with what went on in some of the other houses, the Fijis’ initiation ritual was kept well within bounds by our upperclassmen. On the brighter side, all the shenanigans that we (the Mighty Class of ’46) were put through helped us form a kind of bond, some of which continues to this day. We all made it through and became members of Sigma Tau Chapter, Fraternity of Phi Gamma Delta. When I say all, I mean just that. There were 41 men in our class. Six more were pledged after I left for the Navy in April. One man dropped out; the rest of us were initiated. This made a grand total of 46 in the class. I could never name them all now; as freshmen, we had to.

HELL WEEK OVER, I WAS BACK IN GEAR IN MY CLASSES AND at the shellhouse when I received my long-expected “Greeting” from Uncle Sam. Having registered for the draft when I turned 18, I was now directed to present myself for induction into the armed forces. My number was up, and I was ready to go. I stopped rowing, dropped all my classes and went to the induction center for my physical. I did so with some trepidation, afraid I could not pass 100 percent. A urinary anomaly had been discovered the previous summer when I applied for admission to the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps (NROTC) at the university. I failed that physical because of the presence of albumin in my urine. I had gone to see a urologist who, after testing urine samples taken upon arising, assured me that there was no problem. In his opinion, the symptoms were caused by the excessive physical stress of rowing. That opinion made no difference to the Navy doctors, and I was out. Albumin in the urine, not serious enough to warrant 4F status, meant only one thing — the Army. At the Induction Center, despite my fears, luck was with me. The corpsman on duty who happened to handle my sample turned out to be Harry Pitzer, a member of my Fiji pledge class. He had been drafted into the Army just a few weeks

I – Shoving Off (1923–1947) – 16 previously. He spotted the albumin right away, and, when he saw my name on the vial, came looking for me. He asked whether I thought serving in the Navy or Marines sounded better than serving in the Army. I said “yes,” so he marked the sample “OK.” With that hurdle out of the way, I opted for the Navy over the other services, thinking that it might offer the most decent way to fight a war. A day or so later, I was hanging around the Fiji house when a phone call came in from the dean of students, Mr. Condon. A Fiji alumnus, he had taken an interest in me and, without talking to me first, persuaded the draft board (of which he was a member) to defer my induction until after the end of Winter Quarter. I had been all set to go and was not properly grateful. I should have been. The unexpected deferment meant that I would not be heading for Navy boot camp at Farragut, Idaho, in the dead of winter. Also, I might otherwise have missed my chance for the V2 training program, which became available while I was still in boot camp. As they say, “It’s an ill wind….” The unexpected delay forced me to go to my several professors, make peace with them and, worse, try to make up all the work I had let slide. The only one who would not give me a break was the captain in charge of Army ROTC — a course required in those days of all male students (except those in Navy RO, which is what we called NROTC). He insisted that I make up every minute of the time I had missed and all the work as well. He said that he thought me a slacker, and that I should have been proud to enter service as soon as I could. I managed to make up all the missed time and work and finished my classes for the quarter with fairly good marks. I didn’t go back to the Frosh turnout, there seeming to be no point since I would be gone by the time racing season started. Nevertheless, the delayed induction allowed me to win my first UW rowing letter. With my induction date only a few days away, I received a phone call from the Lightweight coach, Gus Eriksen. Grade reports had just come out, and his Varsity stroke was ineligible. His crews had races

Off to the races – Vancouver Rowing Club – circa 1930 coming up against the University of British Columbia (UBC), and he asked whether I would come down and fill in. I hadn’t rowed for weeks and had done nothing to keep fit. Though reluctant to do so, I let him persuade me. When I showed up, he stuck me at stroke in his first boat. I did not stop to think how much this might be resented by the squad. Fortunately, the first boat continued to beat the second, and I was accepted. After our workout the first day, someone who had been in the launch accosted me and said it didn’t look as though I were pulling much. He was probably right, but I passed it off by saying I was not back in condition yet. He might have been giving me an unintended compliment. Years later, when coaching, I liked to insist that my oarsmen “row hard, but make it look easy.” Our two crews left without me, for I had to appear before the draft board and persuade them that I was not running to Canada to avoid military service. Eventually reunited in Vancouver, we went for a workout. At that time UBC was rowing out of a miserable old shack

I – Shoving Off (1923–1947) – 17 on the Fraser River, not out of the picturesque Vancouver Rowing Club boathouse at Stanley Park. They had only two usable eights. One was a brand-new boat from England, the other an old shell of Dad’s make. Being good sports, the UBC crews proposed that we draw lots. We preferred the “Pocock” and, luckily, drew it. Both our crews won, helped by our shouts of “F.E.R.A.” (the initials standing for a phrase I absolutely refuse to divulge). I embarked on my Navy career two days later, secure in the knowledge that I possessed a Varsity Lightweight letter from the University of Washington. I never heard who had flunked out and given me my big chance. On the first of April, 943, Mother and Dad drove me down to the railroad station to catch the train that would take me to boot camp. Seeing them standing there, looking so lost and forlorn as we all were marched off, I was too young and far too dumb to wonder what it all might mean to them. I had thought about the possibility of dying, but mistakenly believed that such a fate involved me and no one else. Had I known how badly our Navy was being mauled at the time, my thoughts might well have been on an entirely different plane. [FOR THOSE WHO DON’T KNOW WHERE THE TERM “BOOT CAMP” came from, here’s the story: Trainees for the Navy, rated as “Apprentice Seamen,” were not allowed to swagger around in their bell-bottom sailor pants. Instead, they were forced to wear canvas leggings, similar to what Boy Scouts once wore, known as “boots” in Navy lingo. Trainees were called “boots” and the training facilities, logically enough, were called “ boot camps.” Upon graduation, as Seamen, First Class, they could swagger in their bell-bottoms all they wanted.] MY EXPERIENCES AS A BOOT WERE TOLERABLE. BECAUSE I HAD rowed at the UW, and survived Hell Week at the fraternity house, there was not much the boot camp sadists could do to surprise me. I lost lots of sleep (the snoring in the barracks at night was unbelievable) and soon could lie down and sleep anywhere when we had a few

minutes to spare. One evening I was flaked out, recovering from the trials of the day, when mail call sounded. There was a letter from Dad with a clipping of a column by Royal Brougham, the sports editor at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer (P-I), describing his recent visit to Farragut Naval Training Base. He rhapsodized over this luxurious summer resort on the shore of Lake Pend Oreille where the nation’s young men were being introduced to the joys of life at sea. I suspected he was shown only the Officers Club. After a few weeks of these ordeals, I came down with catarrhal fever and had to endure a month-long stay in the hospital. Forced to start over with a new company, I had to go through much of the same boot camp regimen a second time. One day, I unwisely volunteered to row in a cutter crew in preparation for the intercompany races. Another member of our company said that he had rowed at the University of California (Cal), while I confessed to having turned out at Washington. I was put at starboard stroke; the man from Cal was put at port stroke. This meant I was supposed to follow him. When the command to row was given by our coxswain, the Cal man missed the water completely and landed in the bottom of the boat. I made the mistake of telling him what he was doing wrong. That evening I was royally read off by the company commander in front of the whole company for my bitching. Incidentally, he was the coxswain of the cutter. He ordered me to run several circuits of the grinder (parade ground) with my rifle over my head. So much for trying to help. I wasn’t kicked off the cutter crew — no one else would volunteer —and we enjoyed some pleasant outings. Boating on Lake Pend Oreille, even when sweating behind the 6-foot oar of a navy cutter, beat marching up and down the grinder. Mr. Monroe (emphasis on the first syllable), 23 at most, had been a star athlete at some school in Texas before joining the Navy. He held a Specialist (A) Chief Petty Officer’s rating. Carrying the fancy, hand-carved, gold-painted wooden saber he used to emphasize his every command, he was MISTER MONroe to all us boots. He

I – Shoving Off (1923–1947) – 18

In front of the “Fiji Annex” – 1945 probably hated being there as much as we did. Graduation ceremonies for Company 373, Regiment 2, Battalion 8, consisted of our parading back and forth in review with Mr. Monroe waving his sword. What all the marching we did as boots had to do with being sailors in the Navy, I never figured out. And then the wait, wondering where I would be assigned. We spent days shoveling dirt into wheelbarrows and hauling the loads to one end of a field. When the pile was big enough to suit the cretin in charge, he had us haul it all back to where it came from. The only pitch I remember, relative to my future in the Navy, was one urging duty with the submarine service. Fifty dollars a month extra and guaranteed good food didn’t seem sufficient inducement. I actually went out (or down) in a “sardine can” years later and found the wisdom of my non-interest confirmed.

Because I had some college work behind me, I was given the job of company clerk for our barracks. In that capacity, I learned something of how the Navy functioned. I also learned to drink coffee. One day a notice came through announcing an exam being offered. Those passing it would qualify for officers’ training through the newlyestablished V2 program. Asking myself “Why not?” I took the exam and was one of the few who passed. I would be assigned to the University of Washington if I could pass a rigorous physical exam; the dear old albumin again. I figured I would solve the problem on my own this time. Finding an old ink bottle in the barracks (ballpoint pens had yet to be invented), I washed it out and ditched it in my ditty bag. The morning of the physical, I filled it with the proper stuff, hid it in my baggy GI jumper and went to the sick bay at the appointed hour. The first thing the corpsman on duty asked for was a urine sample. I said I would have to go into the head, i.e., toilet, and run some hot water on my hands to hasten the process. (Using the right words seemed the sole criterion for qualifying as a sailor — that, and drinking coffee). This was not an unusual request, and the corpsman said “OK.” I filled the beaker from the jar I had brought with me and, after running hot water over the bottle to make it seem authentic, took it to the corpsman, who passed me with flying colors. That hurdle out of the way, I returned to classes at the UW. Every six months for the next two-and-a-half years, I had to pass another physical. I solved that problem by making sure I took mine at the same time as my room mate and buddy, Bob Lorentz. I knew he could pass the urine test, and he agreed to pee for me. Dodging the war was not the issue. We had no idea how long it would last and figured we would all end up in it sooner or later. It was more a matter of our wanting to go to war as officers rather than as enlisted men. One friend, Mike Coles, who had flunked out, told me years later that, almost before he knew it, he found himself driving a landing barge onto the beach of some South Sea island. In an instant, the barge capsized on top of him. At least he survived. Many did not.

I – Shoving Off (1923–1947) – 19 down to Dad’s shop at the lower end of the campus and worked at one project or another, or borrowed his car for momentary escape. One had to be careful doing this because we wore only undress blues on campus, while dress blues were required when on liberty. I would have been in big trouble had I been caught.

UW V12 Varsity – 1945 – left to right: Dehn, Dresslar, Bergeron, House, Martin, Swanson, Graul, Pocock, Lee The V2 program was a lousy way to go to college, though it was at taxpayers’ expense. We had a heavy class load — 2 hours — and a full four quarters per year, with little time for fun and games. Despite this, there was some relief to be had. The Fijis sprinkled throughout the Naval ROTC, Marine and Navy units rented a small house at the corner of 2st and NE 45th, just across from campus. We called this our Fiji Annex. Against all V2 regulations, this hideaway helped brighten our otherwise thoroughly regimented lives. We could dodge across 45th during the few floats we had and plan our various weekend capers. Another saving feature was the nightly liberty until 0 o’clock that I could enjoy as long as I kept my grade point at 3.5 or better. Pulling down good grades most of the time, I could walk down to the Ave now and then in the evening to take in a movie at the Neptune or the Egyptian theater — 27 cents. During the day, I often went

INTERCOLLEGIATE ROWING BEING A VICTIM OF THE WAR EFFORT, there was no official crew program at the UW. Ulbrickson was on leave from coaching and serving as acting athletic director for the duration. Football and basketball were kept alive, though for the life of me I can’t imagine why. Perhaps it was to con the public into thinking that the country was not into anything very serious as far as the war was concerned. Though crew had no official status, we managed some rowing through the efforts of Captain Paul Moore, head of the Marine Corps detachment. Captain Moore had rowed at Yale as an undergraduate and was back from harrowing duty in the South Pacific. A near brush with death on Guadalcanal had earned him this stateside rest. Moore’s experiences on Guadalcanal had given him pause to think seriously about life and about what it meant to him. Because he was spared when so many others were not, he had decided to spend the rest of his life working to help others. After leaving the Marine Corps at war’s end, he studied for the ministry and became an Episcopal priest. When last I heard of him, he had just been named Bishop of New York. Moore had persuaded the commandant, Captain Eric Barr, to let him establish a V2 rowing program. With turnouts only three days a week, it never became a drag, and it beat exercising in the gym. We actually had two races: one with an eight from the Coast Guard, the other with a boat from UBC. The first contest was organized by Phil Lewis, he with the wherry on Portage Bay. In the Coast Guard at the time and stationed in Port Angeles, he had borrowed an old eight from the UW and had some people rowing. The race was held on Lake Washington. The Coast Guard crew were no match for us, but we all had a good time. We even enjoyed a social hour afterward at

I – Shoving Off (1923–1947) – 20 the Seattle Yacht Club. The second race, with UBC, was a disaster for me and our crew. I stroked the boat, as I had done against the Coast Guard. Before leaving for the start, I noticed that my rowlock would not close properly, but thought nothing of it. As is too often the case on race day, a strong wind was blowing, and the water was extremely rough at the starting line. When the starter shouted “Row!” my oar, buried in a huge wave, popped out of the lock. No one bothered to stop the race, though by all the rules of racing someone should have. Normally, any breakage in the first 30 seconds stops a race if the cox’n requests it by raising his hand. Either ours didn’t (if he did, no one in the official’s launch saw it), or — what is more likely — the officials knew nothing of such things. So the race went on. While the other seven rowed, I fiddled with my oarlock. I jammed the oar back in, though still unable to close the gate. We took off and rowed right past the other crew. When the oar came out again, we dropped back. With the oar back in, we once more surged ahead. Out it came, back we fell. By this time, I was cussing bloody murder at whoever had made the lock, as well as at anyone else I could think of. Each time I got the oar in place, we regained the lead until, inevitably, the lock gave way completely. All I could do then was slide up and down with the rest of the crew. They held the other crew, more or less, but we lost by a few feet. The UBC crew were ecstatic. This was the first time, ever, that a crew of theirs had defeated a crew representing the University of Washington. At least one of the victors was realistic, however. Back at the shellhouse I heard him mutter to one of his mates, “Yeah, but we only beat a seven, not an eight!” ONE DAY IN AUGUST, 945, AS WE M ARCHED ACROSS THE campus, I heard someone shouting that an atomic bomb had been dropped on Japan. Despite the unimaginable horror of that, it was a relief to know that the whole miserable business was about to end. I wanted to end my career in the Navy (what little there had been of it) right then. Of course, there was no way that all of us could

be returned to civilian life immediately. The following March I completed the courses required by the Navy and was commissioned Ensign Pocock in the U.S. Naval Reserve. The war was over by then, thank heaven. I bought all the necessary uniforms, had my picture taken for posterity and flew (my first airplane ride — 14 hours to New York) to my new duty station. During the flight, spent next to a fellow who was violently airsick for most of the trip, I arranged to get together with one of the stewardesses after we reached New York. That liaison collapsed — luckily or not, depending on how one looks at it — before it even began. When the door of the plane opened to let us out, there at the foot of the stairway, waiting to greet me, stood Don Dehn. An old friend from school and rowing, he was also in uniform and stationed at Newport, Rhode Island, where I was heading. He had gone to the trouble of finding out when I was due in and was there to take me under his wing. It was great to see him, although he was not nearly as pretty as the stewardess. With some time to kill, we spent a few days enjoying the city. I then went up to Newport for two months of further training, followed by a few weeks aboard the USS Montpelier while waiting for my number to come up. Our squadron of three heavy cruisers made a sortie down the coast to Bermuda, where we stayed for several days. At the time, motor vehicles were still not permitted on the island. Several of us rented a horse and carriage and went up to one of the posh hotels overlooking the bay. Everything was free to those in uniform, and we had a great time. I found myself in no great hurry to return to civilian life, at least not until after we had departed that paradise. Soon after we returned to Newport, my papers came through and I made my way back to Seattle to be discharged. Rather than spending what little money I had, I decided to try the Military Air Transport Service. (MATS was free to all military personnel.) I made it to Philadelphia and there hopped a ride in a Piper spotter plane that took me as far as Detroit. Required to wear a parachute, I wondered how scared I would have to be before I would be willing to use it. Fortunately, I didn’t have to find out.

I – Shoving Off (1923–1947) – 21 I requested a day’s delay, wanting to clean myself up before going through the required physical (no urine worries this time). I received the delay (and was even paid for it) and came back the next day to satisfy the medicos. Suddenly, I was a civilian again — though still in the Naval Reserve — with a so-called "ruptured duck” service pin which attested to my having been willing to stick my life on the line like everyone else. I had been a whole lot luckier than many.

Aboard USS Montpelier – 1946 – Bo Morgan, author & Brooks Biddle Then followed a flight to San Diego in a DC-3 cargo plane. I remember hanging out the open door watching the world go by. Upon reaching San Diego I struck out. I found the bus station and was about to buy a ticket for Seattle when a fellow sidled up to me and asked where I was going. When I told him, he said he was heading that way and was looking for another paying passenger. I think he wanted 65 dollars. It was cheaper than the bus fare, so I said OK. Excusing myself, I went into the head, took the last 00 dollar bill I had and stuck it inside my sock as a precaution in case the guy tried to roll me. I’m sure that if he had chosen to stick a knife or a gun in my ribs, I would have been only too happy to hand it over. We headed north in his beat-up old Buick that didn’t sound as though it would make it as far as Los Angeles, much less clear to Seattle. Actually, we made it to Sacramento before it gave up. The driver gave me some of my money back, and I found another bus station. I arrived in Seattle on the day I was due to be discharged.

ALL I NEEDED TO COMPLETE MY DEGREE IN CIVIL ENGINEERING was five hours more credit. I could stretch that out for a year and row at least one season. Any more than that would have seemed irresponsible, although I still had three full years of eligibility. I enrolled at the UW under the GI Bill — 50 dollars a month, plus tuition and books — and went out for crew. Ulbrickson was back on the job. The Cal race was scheduled to be resumed, as was the big annual regatta at Poughkeepsie, so there were goals to aim for. Class work posed no major problem. What bothered me, though, was that all the strenuous exercise and fresh air made it hard to keep awake at night to study. As if this were not enough, I could not relax when I lay in bed. The only place I could sleep was on the floor. That had worked in boot camp, and it worked for me now. Every night I flopped out on the floor for a few hours’ sleep and did my studying early in the morning. For Spring Quarter I arranged a light class load. Two days a week I had no afternoon classes and would take the bus home, grab a nap, gulp down a raw egg in vinegar (something the old pros thought did some good) and walk to the shellhouse in time for turnout. One day I overslept and woke up close to four o’clock, which was the time we hit the water. I didn’t dare miss turnout because Ulbrickson was sure to put me in the last boat the next day. Running as hard as I could the several miles to the shellhouse, I arrived just as the lineups were being announced, so tired that I could scarcely

I – Shoving Off (1923–1947) – 22 lift my oar out of the rack. Somehow I made it through the workout, though I didn’t pull much. I was in the stroke seat, so no one in the boat could see my puddle. Al didn’t notice, and I kept my seat. During Winter Quarter that year the Varsity Boat Club — anyone who turned out his sophomore year was automatically a member — tried to recapture some of its past glory. Prior to the war, one of the major all-university social events each winter had been the annual Varsity Boat Club Ball. The most recent one had been held during my freshman year, 942–43. Because of wartime restrictions, the venue had been the old Army ROTC Armory on campus. This time we were determined to go all out, not recognizing that such affairs were likely to leave the new breed of student cold. We rented the National Guard Armory — the biggest place in town — paid through the nose for an orchestra and spent untold hours hauling down boats and oars and other equipment to decorate the hall. On the night of the dance, not counting the oarsmen and their dates, there were more people in the band than on the dance floor. Once over the shock of the financial disaster we faced, those of us who were there had a great time. As in the old saying, “Eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow….” In the cold light of day, there was no getting away from the fact that we were in deep trouble. Everyone in the VBC was forced to chip in — I don’t remember how much. Weeks later, the club treasurer, Bob Barr, hung a big sign on the bulletin board next to the “hot hole” (our name for the room where we dried out our wet sweats) which read, “By the great Caesar’s jock strap, we’re solvent,” and we all breathed more easily. Whether there were any other attempts at alluniversity dances that year, I have no idea. We were all supposedly in training during the spring racing season. Many college athletes (and most oarsmen) actually did that in those days. Smoking, drinking and social events took a back seat.