13 minute read

The Blair affair

By Alan Wares

“Things can only get better!” belted out the D:Ream hit, on auto-repeat across the South Bank in the early hours of May 2nd 1997. (NB: if you’re going to have a party - and a big one at that - at least bring along a second record.) The Prime Minister-elect Tony Blair, had just secured an astonishing landslide General Election victory for Labour, and addressed the crowd promising that “we were elected as New Labour, and will govern as New Labour”.

These were uncharted waters, especially as ‘New Labour’ was a phrase - totally unofficial - attached to a hitherto socialist party that had no real intention of governing as a socialist party.

That a highly charismatic Blair was expected, in the run up, to win the General Election was a safe and secure bet, though the size of this victory raised many eyebrows across the political spectrum. As incumbent Conservative Cabinet Minister after Cabinet Minister was blown away by the Labour or Liberal Democrat opposition, mostly as a result of the sleaze and corruption Platinum wrote about in issue 92, Labour’s majority of 179 was the largest the party had ever seen. For the next 10 years, Tony Blair held sway over the twists and turns of the United Kingdom, domestically, and its relationships with Europe, the United States, the Middle East, and the rise of the Islamic jihadis. But he will mostly be known as a Prime Minister who ignored advice, evidence and plain common sense for so long to take the UK into an unnecessary, unwarranted and, ultimately, illegal war with Iraq.

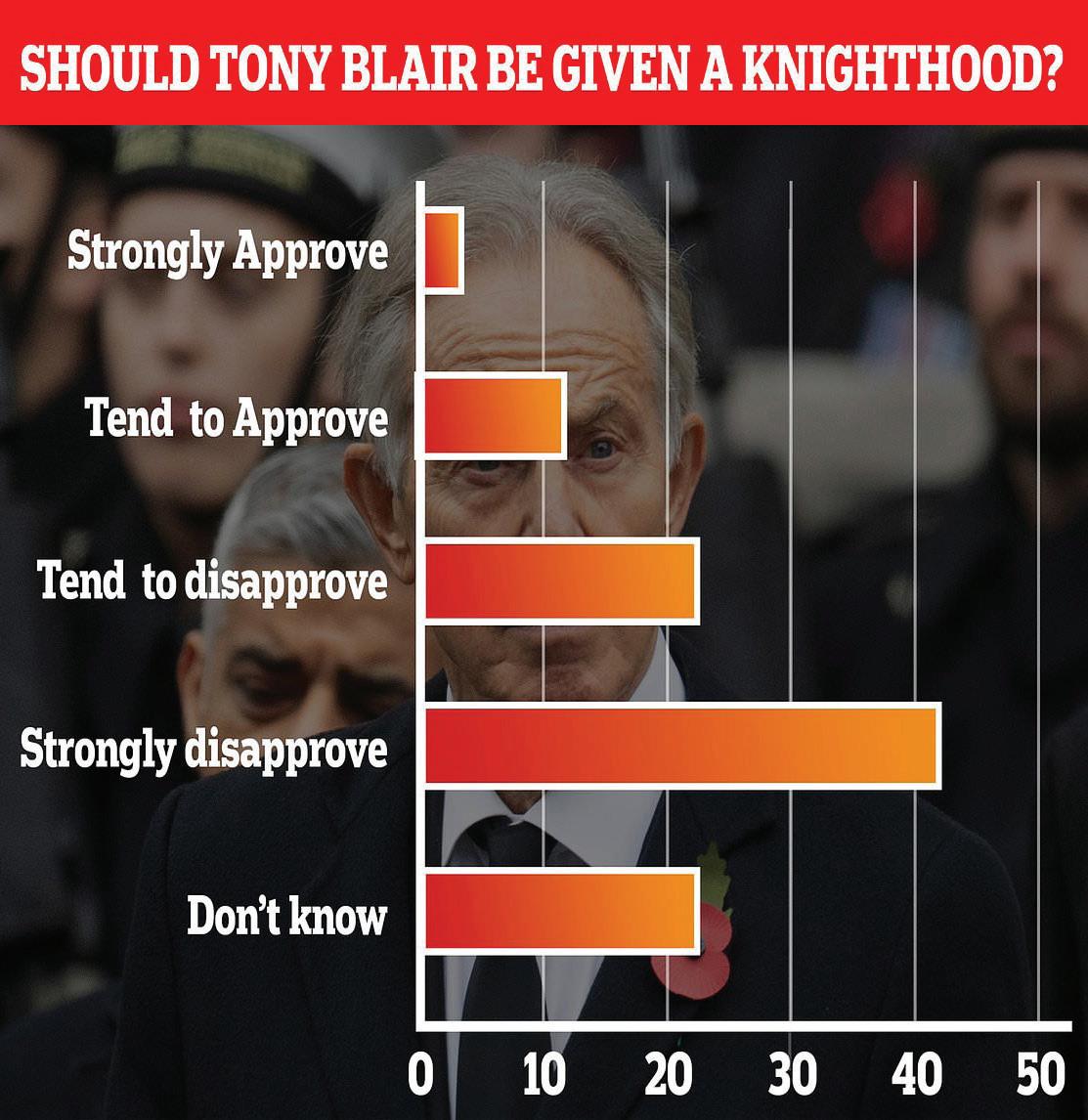

Now, 25 years after his election victory, and nearly 15 years since leaving office, Tony Blair has been offered a knighthood. At the time of writing, 1,133,335 people have signed the petition to have this honour removed. So the question that now remains is - does Tony Blair deserve his knighthood?

Anthony Charles Lynton Blair was born in Edinburgh on May 6th 1953. After attending the independent Fettes College in his home city, he studied at Oxford and eventually qualified as a barrister. At the age of 30, he was elected into Parliament at the 1983 General Election for the constituency of Sedgefield in Northumberland, having been soundly beaten the year before in a by-election in Beaconsfield in Buckinghamshire.

From his first dabbling’s in local politics in east London in the mid-1970s through to his time as being made Leader of the Opposition in 1994, it’s not unreasonable to say Blair shifted his personal political beliefs along with those of the hierarchy of the Labour Party. He would say in the early 1980s, while Labour was led by traditional socialist Michael Foot, that he was ‘a socialist; man of the Left’, before venturing, under Neil Kinnock’s leadership, that he was ‘very much of the centre left’.

During his rise through the Parliamentary ranks in through the 1980s and 90s, he would be noted as a reformer. He was disappointed in Labour only focusing on a narrow part of society which he felt was a shrinking one anyway - that of the working-class voter who was a trade unionist in subsidised council housing. Rather than stick with those hard-core supporters alone, Blair took the approach of reaching out to those same people but who had been encouraged to aspire by Margaret Thatcher, to buy their own council homes, to own a car - the new middle-class - which both parties had hitherto been ignoring.

In 1992, when Neil Kinnock resigned his post as leader of the Labour Party following the Conservatives’ fourth election victory in a row (albeit one which they were not expected to win), reformer and strong frontbencher John Smith was elected the new leader. He immediately brought in Tony Blair to his shadow cabinet. Realising that Labour’s

narrative was being dictated to by the Tories and the press (‘Labour are the party of higher taxes, higher interest rates’ etc., notwithstanding Margaret Thatcher had overseen those problems and worse during her first term of leadership), they set about updating - if not the party - then at least the party’s image.

When, in 1994, John Smith – probably the UK’s next Prime Minister, given both parties’ direction of travel in the polls - died in office of a heart attack, Tony Blair was seen by Labour members as the safest pair of hands to lead, and carry on Smith’s agenda.

Every opinion poll since late 1992 had put Labour ahead of the Tories, with the lead being a variety of chasm widths. The 1997 General Election result was never really in doubt, though Blair himself refused to admit this until he saw the result for the constituency of Hove come in. It wasn’t until 3.45am on May 2nd that Blair finally acknowledged “I think we’ve won.”

Domestically, the ‘New Labour’ project sought to reverse many strands of 18 years of Conservatism; a Conservatism that had lost ‘Middle England’. In the first Parliament, they sought closer co-operation, and therefore clarity, with the EU (something Labour had been split on in the 1970s); shorter NHS queues, introduction of SureStart, the minimum wage, a vote on devolution to name a few domestic policies that helped him secure another landslide in the 2001 General Election.

In his second Parliament, he (finally) rescinded Section 28 from the Local

Government Act 1988; an Act which had sought to criminalise education of homosexuality, and the introduction of the ban of hunting with dogs.

However, despite a fair amount of domestic gains - and a few defeats and reversals - there is one albatross that Blair may never shake off.

Following George W Bush’s presidential election victory in 2000, US government policy sought to remove Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq, at whatever the cost. In the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Centre in New York, Bush sought to punish Hussein, blaming him for the attack. He formulated a notion of a ‘War on Terror’; a meaningless phrase, and proving ultimately unwinnable.

Despite clear international evidence, including historical precedent, three decades of trade with the West, and reports submitted to Bush himself, it was found that there were no links between the Iraqi regime and Al-Qaeda. It was ludicrous to link them in the first place given that Hussein had run Iraq on largely secular lines since 1979, and had no time for any religious extremism.

But Bush wanted his war. He would use the lack of evidence of not being able to find weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) as a reason for saying Iraq had WMDs. His case was enhanced when Iraq refused further co-operation with UN weapons inspectors. So, Bush pressed ahead. He managed to persuade the American public, not generally noted for its knowledge of international affairs, and US Congress, that Saddam Hussein’s regime posed a threat to the West.

Operation Desert Storm, which took place across Iraq in 1991 to push Hussein back from his unilateral invasion of Kuwait, had largely cleared away any notion of that nation having a military of any note. The United Nations policy of containment, enthusiastically supported by the Security Council members (including the US and the UK), was working and still in place. Hussein was basically little threat to the West. But Bush didn’t want to be seen to go it alone. He wanted the coalition his father had secured for the original invasion of Iraq 12 years earlier. He didn’t get it.

But he still managed to persuade Tony Blair to ride gung-ho into the Middle East with him. Despite so little evidence of Iraq’s WMD programme, its threat to the West, its capability to cause havoc, onwards into the dark pitches of war Bush and Blair sauntered.

An unprecedented one million people marched through London ahead of the 2003 invasion, with an estimated 36 million people worldwide, protesting at the lack of evidence the UK government was providing its citizens and UK Parliament as justification for going to war. They felt then, as they still feel now; that this was an illegal war. Blair’s behaviour cost him three senior Cabinet members who resigned in disgust, including the highly-respected Robin Cook.

In the end, Blair won his argument in Parliament, but only after he had presented false accounts (the so-called ‘Dodgy Dossier’ - a briefing of such scant intelligence as to render it worthless), thin advice from US attorneys who had declared any potential invasion as ‘legal’ despite offering little evidence, and by sheer force of personality.

The legacy of that invasion is still being felt today, nearly two decades afterwards. Estimates of between 150,000 and 1.1m non-combat Iraqi people (i.e. civilians) died as a result of the initial invasion - plus tens of thousands of military personnel, and the insurgency over the next eight years that the lack of planning by the US and the UK had encouraged.

It gave succour to Islamic extremist groups - many of whom had been at the bitter end of Saddam Hussein’s massacres with them - to rise up and inflict their retribution on the population, and onto unwelcome international forces.

The 2016 Chilcot Report, an inquiry into the UK’s decision to go to war, eventually concluded that not every alternative had been examined, that the UK and US had undermined the United Nations Security Council in the process of declaring war, that the process of identification for a legal basis of war was “far from satisfactory”, and that, taken together, the war was unnecessary.

And no WMDs were ever found.

And that’s to say nothing of the efforts the UK ended up putting in to seek out the Islamic extremists training, fighting and hiding across Afghanistan, and the rest of southern Asia. Afghanistan, a country the British tried to control in the 19th Century; where the Soviet Union, invited in by a tame government tried to exert its authority; and where the US under Bush had a crack at its impenetrability. And all left with their tails between their legs.

So with hundreds of thousands, probably millions, of dead and injured, and a further destabilisation of the Middle East, and the rise of new Jihadis, does Tony Blair deserve his knighthood?

Tony Blair is being offered the most senior knighthood available in the UK honours system - The Most Noble Order of the Garter. Appointments are made at the sole discretion of the Monarch - as opposed to recommendations from the Cabinet - and is usually offered to those who have served at the highest levels of public life. There are never more than 24 Knights Garter, though Blair would become the 20th incumbent. To look into one aspect of whether he should receive his knighthood, let’s look at the current day thinking of ‘why’. The petition on Change.org challenging Parliament to remove Blair’s honour is worded ‘Tony Blair caused irreparable damage to both the constitution of the United Kingdom and to the very fabric of the nation’s society. He was personally responsible for causing the death of countless innocent, civilian lives and servicemen in various conflicts. For this alone he should be held accountable for war crimes.’

Herein lies a petition in two parts. For his part, Angus Scott, who started the petition, doesn’t elaborate on the meaning of ‘irreparable damage to the constitution to the UK and the fabric of

society’. Both are abstract concepts which can held open to a wider - very wide - debate. One wonders if Angus has seen what the current incumbent is doing to the constitution of the UK?

However, it’s the second part, and specifically Blair’s approval to send British troops into Iraq and Afghanistan that has touched on the nation’s ire for so long. For many, he is an unconvicted war criminal. For those who wish to have this honour rescinded on behalf of all those who lost their lives in Afghanistan and Iraq, this petition is aimed at Parliament for it to debate. Unfortunately for the petition signatories, Parliament has no say in this appointment.

Additionally, Blair has moved into that rarefied strata of international statesman; a world diplomat; part of a global ‘Elite’; an untouchable. And for that reason, those who wish to see him on trial at The Hague will probably never get their day in court.

There is one additional consideration as to whether Tony Blair deserves to put ‘Sir’ at the front of his name. The UK Honours system itself has, probably since it started, long had a reputation as a system of rewarding mediocrity or worse, cronyism and nepotism. Many public figures - political and apolitical, Left and Right, male and female - have refused an Honour from their country on the back of what they feel is a outdated system. So what value a knighthood now? Even Lynton Crosby has one, and he’s partially responsible for Boris Johnson’s behaviour now.

Blair left national and international party politics in 2007, when he resigned as Leader of the Labour Party (and hence as Prime Minister) ahead of Gordon Brown’s coronation. Since then, he has taken up many international diplomatic roles, including - incredibly enough - as a peace envoy to the Middle East. No, really. But what he also did was to arrogantly walk away from the carnage he helped create four years earlier, without a hint of regret, still justifying it with the line about Saddam Hussein’s apparent menace in the region.

For the fact that Blair led his country, including 10 years as a leader with a strong track record domestically and, until 2003, internationally, a very strong case is made for his knighthood. Many on the Conservative side of the House have commented or even praised his role as a statesman and politician during his time as Prime Minister. He is respected, at least in that regard. Additionally, Sir John Major is also within the elite group of 24 making up the Knights Garter; he was Prime Minister for seven years, and look at the ongoing corruption he had to deal with.

Conversely, for the utter disdain and contempt with which Blair treated his own party, his own people, the international community and, most concerning of all, the innocent people of Iraq and Afghanistan, a question of a knighthood ought to – in times more enlightened than ours – be considered a farce.

Sod it - let him have his knighthood. The debates into his worthiness will be meaningless, and HM The Queen will bestow it upon him anyway and we, the general public, have no say in the matter.