13 minute read

The “Whiskey Rebellion

By John L. Moore

Farmers objected when Robert Johnson began performing his duties as a federal tax collector for Allegheny and Washington counties in Western Pennsylvania in 1791. After all, Johnson’s job called for collecting the newly imposed U.S. tax on whiskey, a product made by many of the farmers in those counties.

Johnson quickly ran into trouble. “A party of men armed and disguised way-laid him at a place on Pidgeon Creek in Washington County, seized, tarred and feathered him, cut off his hair, and deprived him of his horse, obliging him to travel on foot a considerable distance in that mortifying and painful situation,” Alexander Hamilton later reported to President George Washington.

As secretary of the U.S. Treasury, Hamilton was the federal official responsible for collecting this tax. His August 1794 report made it clear to Washington that Western Pennsylvania was in open revolt.

Known to history as The Whiskey Rebellion, the conflict had been raging for three years. In western Pennsylvania, “people, assembled in arms, chased off the officers appointed to enforce the law, tarred and feathered some of them, singed their wigs, cut off the tails of their horses, put coals in their boots, and compelled others to resign,” 19th century historian I.D. Rupp reported. “Their object was to compel a repeal of the law …”

Tinkers were tradesman who mended pots and pans, but they also repaired stills. As the insurrection heated up, a shadowy figure calling himself Tom the Tinker became a spokesman for the rebels.

“Advertisements were put up on trees, and other conspicuous places, with the signature of Tom the Tinker, threatening individuals, admonishing, or commanding them,” Rupp reported. “Menacing letters with the same signature were sent to the Pittsburgh Gazette, with orders to publish them — and the editor did not dare refuse.”

The Gazette was the first newspaper west of the Appalachian Mountains.

Drinking whiskey had become widely accepted during the 1700s. Much of the country’s water wasn’t fit to consume, and “to drink whiskey was as common and honorable as to eat bread,” Rupp said in his 1848 book, “Early History of Western Pennsylvania.” By the 1790s, rye had become the principal crop of Western Pennsylvania farmers. But they produced more than they could consume. Also, the grain was too bulky to ship over the mountains to the eastern markets on pack horses. “A horse could carry but four bushels,” Rupp reported. But when the farmer used the grain to produce rye whiskey, the horse “could take the product of 24 bushels in the shape of alcohol.”

In many cases, the farmers who grew the rye were the same people who produced the whiskey.

As detested as the tax became among farmers, the federal government urgently needed the revenue that Johnson and other federal agents sought to collect. During the 1770s and 1780s, the United States had incurred huge debts to finance its eight-year rebellion against Great Britain.

During the early 1790s, the U.S. Congress decided to pay off the war debt by levying a tax on whiskey and other spirits – and on the stills used to make them. Sensing the sentiments of their constituents, U.S. Rep. William Findley and other congressmen from Western Pennsylvania unsuccessfully opposed the measure.

The incident involving Johnson the tax collector happened on September 6, 1791. Federal authorities quickly identified three suspects – John Robertson, John Hamilton, and Thomas McComb – and began legal proceedings against them.

← Washington reviews the troops

As commander-in-chief of the U.S. military,

President George Washington left Philadelphia, then the country’s temporary capital, and led militia troops to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion in Western

Pennsylvania. This painting by Donna Neary is titled

“To Execute the Laws of the Union (The Whiskey

Rebellion).” It shows Washington in Harrisburg in

October 1794 reviewing militia troops from New

Jersey that took part in the campaign. (Courtesy of the National Guard)

↑ U.S. Rep. William Findley and other congressmen from Western Pennsylvania opposed the whiskey tax when Congress approved it in 1791.

↑ Tarred and feathered

19th century illustration depicts whiskey rebels riding a federal tax collector on a rail after he was tarred and feathered by people protesting the U.S. tax on whiskey and stills.

According to Rupp, a deputy marshal who acted as a process server lacked the courage to serve notice to the three.

When the task was given to another man, he “was seized, whipped, tarred and feathered, his money and horse taken from him, (he was) blindfolded and tied in the woods, where he remained five hours,” Rupp said.

There were many other episodes during the three-year conflict.

In October 1791, for example, a man named Wilson told people that he was traveling around the country as a Congressional agent to compile a list of all the stills so they could be taxed. This wasn’t true, and Wilson was apparently mentally deranged. But a group of tax rebels abducted him anyway. They took him to a smith’s shop several miles from his residence, stripped him, and burned him with a hot iron. Then they tarred and feathered him, according to Hamilton’s report.

When the court investigated, armed rebels “ventured to seize and carry off two persons, who were witnesses against the rioters in the case of Wilson, in order to prevent their giving testimony … to a court then sitting or about to sit,” Hamilton said.

In January 1794, “William Richmond, who had given information against some of the rioters in the affair of Wilson, had his barn burnt with all the grain and hay which it contained,” Hamilton said. “And the same thing happened to Robert Shawhan, a distiller who had been among the first to comply with the law and who had always spoken favorably of it.”

The whiskey rebels also organized committees, which passed formal resolutions calling for the repeal of the tax and denouncing anyone who approved of it or tried to collect it.

One resolution published by The Pittsburgh Gazette declared that any person who had accepted or might accept a federal office to collect the tax “should be considered as inimical to the interests of the country.” Hamilton told Washington that the measure also recommended that residents of Washington County “treat every person who had accepted or might thereafter accept any such office with contempt, and absolutely to refuse all kind

of communication or intercourse with the officers, and to withhold from them all aid, support or comfort.”

Armed insurgents also terrorized tax collectors. One night in April 1793, disguised men attacked the house of a revenue officer in Fayette County, south of Pittsburgh. When they learned the man wasn’t home, “they contented themselves with breaking open his house, threatening, terrifying and abusing his family,” Hamilton said.

In late November, another party of men, some armed and all wearing disguises, returned to the officer’s

Otter Lake Otter Lake

CAMP RESORT

• 60 acre lake with 300 campsites • Paved roads • Electric, water and cable TV hook-ups; 100 campsites have sewer hook-ups • 8 heated bathouses, store, laundry and propane • Boating, boat rentals and fishing

(no fishing license required) • Indoor pool with 2 Jacuzzis and Sauna • Outdoor Pool • Swimming Beach • Lighted tennis, racquetball and basketball courts • Softball field • Game room, planned activities • Open all year • Woodall 5W rated

P.O. Box 850 • Marshalls Creek, PA 18301 570-223-0123 Reservations only: 800-345-1369 www.otterlake.com

Classic American Fine Dining

Wednesdays - Pasta Fridays Jumbo Cajun Shrimp - Six for $6 Saturdays Prime Rib & Lobster

Sundays - Steak & Shrimp

Gift Certificates available at StoneBar.com • 4 - 4:30 pm Reservations Receive 20% Off • Business Rt. 209 • Snydersville, PA • 570-992-6634

(Just 5 miles south of Stroudsburg) www.stonebar.com

↑ E Gaddis House-LOC

This old photo shows the Thomas Gaddis log cabin in the Fayette County community of Uniontown. According to the U.S. Library of Congress, whiskey rebels erected a Liberty Pole at the house to show support for the insurrection against the federal tax on whiskey and stills. A Liberty Pole was a long wooden pole erected upright in the ground to symbolize defiance of a government edict. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

← Espy House, Bedford, PA, circa 2003

President George Washington used this

Bedford, Pa., house belonging to David Espy as his headquarters in October 1794 when he led marched militia soldiers across Pennsylvania to put down the Whiskey Rebellion in the

Pittsburgh area.

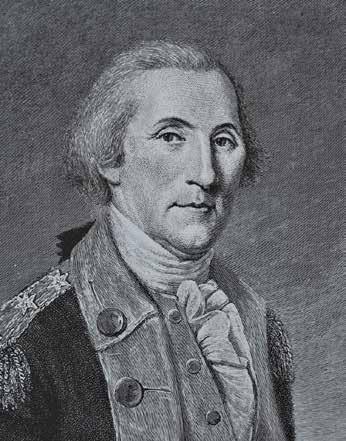

↑ George Washington

During the Whiskey Rebellion, President George

Washington became the first and only U.S. president to ever lead troops in the field.

house. After forcing their way inside, they “demanded a surrender of the officer’s commission and official books,” Hamilton said. “Upon his refusing to deliver them up, they presented pistols at him, and swore that if he did not comply they would instantly put him to death.”

The incident ended when the man surrendered both his commission and record. As they departed, the rebels told “the officer that he should within two weeks publish his resignation on pain of another visit and the destruction of his house,” Hamilton said.

The insurrection continued unchecked into the summer and fall of 1794. The rebels persisted in making it difficult for the revenue agents to collect the tax.

On July 16, 1794 near Pittsburgh, hundreds of armed insurrectionists attacked the house of Gen. John Neville, the region’s top federal tax collector. Although Neville slipped away before the gunfight started, a dozen soldiers from Pittsburgh remained inside to defend the mansion. But they soon surrendered. The rebels then burned Neville’s house to

A bed & breakfast sanctuary where mind, body, and spirit flourish in a relaxing woodland setting.

570.476.0203 | SANTOSHAONTHERIDGE.COM 121 SANTOSHA LANE | EAST STROUDSBURG, PA 18301

Quality Care Providing 40for over years.

GETZ

PERSONAL CARE HOME

• Assistance with Tasks of Daily Living • Delicious Home-Cooked Meals • Extensive Entertainment, Social & Wellness Programs • Medication Management • Family Atmosphere • A Scenic, Country Setting

1026 Scenic Dr, Kunkletown, PA 18058 Route 534 at the Village of Jonas www.getzpersonalcare.com • (570) 629.1334

1794: CENTRAL PA. FARMER USED 2 STILLS TO MAKE RYE WHISKEY

By John L. Moore

Pennsylvania farmers “of any consequence frequently have a small distillery as a part of their establishment,” reported an English traveler who visited the Susquehanna River Valley in Central Pennsylvania in December 1793

The traveler was a lawyer from London named Thomas Cooper. He was riding south along the Susquehanna 12 miles south of Sunbury, in the vicinity of present-day Herndon, when he came to the farm of a man named White.

“White is a respectable farmer,” wrote Cooper, who included details of White’s farm in his 1794 book, “Some Observations Respecting America.”

White employed a number of hands who lived on the farm. They helped him raise rye, a grain that could be used as animal fodder, or, when ground into flour, could become an ingredient in bread. But White, with the help of his farmhands, used rye to make whiskey at the farm’s distillery.

White’s farm and distillery were similar to those of other farmers who doubled as whiskey producers throughout Pennsylvania. Cooper was sufficiently intrigued by White’s operation that he spent nearly a page in describing it:

“He has two stills, the one holding 60, the other 115 gallons.

“To a bushel and a half of rye, coarsely ground, he adds a gallon of malt and a handful of hops. He then pours on 15 gallons of hot water and lets it remain four hours. Then he adds 16½ gallons more of hot water, making together a barrel or 31½ gallons. This he ferments with about two quarts of yeast.

“In summer, the fermentation lasts four days; in winter, six. Of this wash, he puts to the amount of a hogshead in the larger still and draws off about 15 gallons of weak spirit, which is afterward rectified in the smaller still, seldom more than once.”

Cooper was impressed with the result: “One bushel of rye will produce about 11 quarts of saleable whiskey, which fetches per gallon 4 shillings, 6 pence by the barrel.” It’s difficult to translate this amount into 2021 values. According to the U.S. Treasury, it was March 1793 – or nine months before Cooper’s visit to White’s farm – when the new federal mint in Philadelphia began placing coins in circulation. The monetary system was so new and the Susquehanna Valley so remote that it’s impossible to know whether the Pennsylvanians that Cooper met were still using Pennsylvania money or had switched to the new federal coinage.

Be that as it may, “Whiskey in England is usually a spirit drawn from oats. The rye produces the basis of gin,” Cooper said.

Cooper didn’t report how White got his whiskey to market, but it’s likely that he shipped it by boat downriver to Middletown, below Harrisburg, then overland to Philadelphia, one of the largest cities in the United States. To be sure, White was sending other commodities to market that way.

“White gets about 18 bushels of wheat an acre; this he sends by water to Middletown for six pence a bushel, and sells it there [for] 6 shillings 8 pence and six shillings 10 pence,” Cooper wrote.

The traveler reported that the Susquehanna was navigable between White’s farm and Middletown, below Harrisburg. Depending on weather and river conditions, a boat trip to Middletown took from two to four days, Cooper said.

“At Middletown there is a good market for grain on account of a large establishment of mills there,” Cooper wrote. “The boats which navigate the Susquehanna from Sunbury and that neighborhood usually hold from five to eight hundred bushels of wheat, of which the average weight may be 61 pounds per bushel.”

↑ Alexander Hamilton

As secretary of the U.S. Treasury, Alexander

Hamilton wanted revenue from the federal tax on whiskey to pay off debt incurred during the

American Revolutionary War.

the ground. Not long after that, Neville and a federal marshal who had been assisting him fled from Pittsburgh.

Federal officials at Philadelphia, then the country’s temporary capital, decided that the time had come to put down the insurrection.

“President George Washington led an army of 13,000 militia from Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Maryland in October 1794 to quell the Whiskey Rebellion,” said Robert B. Swift, author of “By Great Rivers: Lives on the Appalachian Frontier.”

The militia saw little if any combat. “There were reports the insurgents had agreed to disperse and pay the excise tax by the time the army reached Bedford,” Swift said.

At Bedford, Washington turned the army's command over to Virginia Gov. Henry Lee at Bedford and returned to the nation's capital at Philadelphia, Swift said. Before leaving, the president “issued instructions for the troops to obey the laws, aid the magistrates in bringing offenders to justice and make sure they received fair trials.”

Lee led the army to Pittsburgh where the troops arrested 150 men for their ties to the rebellion. Twenty from this group were taken to Philadelphia for trial.

“Most of the insurgents were found not guilty of charges in federal court, but two men were sentenced to death for treason,” Swift said. “Washington pardoned both men.”