Poems by the Commended Foyle Young Poets of the Year

“To be in the top 15 is an outstanding achievement, one that I will be buzzing about for a long time... it has made me realise that I should share my passion for creative writing with as many people as possible – or else, how can I call myself a writer?” – Angela King, winner, Foyle Young Poets of the Year

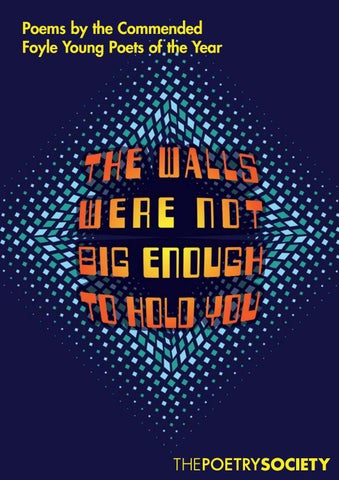

Poems by the Commended Foyle Young Poets of the Year The Poetry Society 22 Betterton Street, London WC2H 9BX, UK www.poetrysociety.org.uk Cover: James Brown, jamesbrown.info © The Poetry Society & authors, 2019 The title of this anthology, The walls were not big enough to hold you, is from Caitlin Catheld Pyper’s poem, ‘Mrs Richards’ Year’, one of the top 15 winning poems.

The walls were not big enough to hold you Poems by the Commended Foyle Young Poets of the Year 2018

Acknowledgements The Poetry Society is deeply grateful for the generous funding and commitment of the Foyle Foundation, and to Arts Council England for its ongoing support. We thank Arachne Press, Arc, Bloodaxe, Carcanet, Chatto & Windus, Divine Chocolate, The Emma Press, Faber, Flipped Eye, Forward Arts Foundation, Inpress Books, Menard Press, Pan Macmillan, Paperblanks, Peepal Tree Press, Penguin, Random House, Penned in the Margins, Picador, Poetry Book Society and Poems on the Underground for providing winners’ prizes. We send our best wishes and gratitude to the judges, Caroline Bird and Daljit Nagra, for their passion and enthusiasm in helping to make this year’s competition such a success. We thank Southbank Centre for hosting the prize-giving ceremony and Arvon for hosting the Foyle Young Poets’ residency with warmth and expertise. Thanks to Marcus Stanton Communications for raising awareness of the competition, and our network of educators and poets across the UK for helping us to inspire so many young writers to engage with poetry and language. Finally, we applaud the enthusiasm and dedication of the young people and teachers who make the Foyle Young Poets of the Year Award the success it is today. foyleyoungpoets.org

Contents Introduction Eira Murphy Matilda Houston-Brown Benjamin Waterer Lai Ling Berthoud Sophie Shanahan Linnet Drury Domi Pila Maya Williams-Hamm Meredith Le Maître Ginny Darke Noah Morrison Cosima Deetman Danique Bailey Jazmine Brett Jasmine Woodcock Will Boagey Iris Gilbert Hayden O’Rourke Ella Christian-Sims Sofia Marliini Heikkonen Naomi Rae Chloe Chuck Rebecca Huang Aisha Mango Borja Morgan Rhys Katherine Spencer-Davis

4 Endings Starting with bees Rhyme Disease Rodger Purpled Geography Me and Dion Side Effects The Oceans They Crossed Marcia From The Amalfi Coast The grandfather clock Tongue Tell me about plantain The Treerific Amputree Stars Witness for the Defence The Office Terms and Conditions 4, 5, 6, my parents’ love: a revolution Psychosis Questionnaire Flower Pressing with Weeds Barnyard Elegy Learning Difficulty Sker Beach Odysseus and Penelope

10 13 14 15 17 18 19 20 21 23 24 25 26 27 29 30 32 33 35 36 38 40 42 43 44 45

Divya Mehrish Adriana Carter Serena Lin Lizzie Freestone

Diseased Self Portrait as a Dying Canary beetlejuice on the woman we found at the beach Evie Collins Starting The Day The Right Way Sarah Feng the good brothers Maia Siegel A Bottle of Zoloft Wins ‘Never Have I Ever’ Niamh O’Toole-Mackridge Pride, 7/7/2018 Alexis Venzon The Letter Samara Bolton Volcanic Father Cleo Martin-Evans A conversation with myself written in Melanin Rory Lewis If Only I Had Known Madeleine Ridout Another Reminiscence Julia Zhou And everywhere, the relief Naomi Tomlin Rhubarb Cindy Kuang my small wife Jessica Xu Departure Beatrice Stewart Big Brother Nandita Naik Mermaid Disease Megan Lunny The Nostalgist’s Guide to Naming the Lizard That Washes Up on Your Porch During the Flood Corina Robinson Learning Masculinity Nia Bolland After the Visitation Gina Wiste Clockmaker Zoë Benton Mouthful of marbles Maya Berardi It’s June In Ohio And

55 59 61 64 66 67 68 70 71 72 74 77 79 80 81 83 84 85 86 88

89 91 92 93 94

Sarah Zhou Fiyinfoluwa Oladipo Amal Haddad Zola Tatton Elinor Bailey Emily Palmer Annie Fan Marina McCready Claire Shang Hana Widerman Ziqi Yan Isla Defty Alisha Gokal Ruby Evans Sophie Paquette Amaani Khan Donovan Timmins Carys Bufford Maymuun Ali Sadali Wanniarachchi Sophie Norton Natalie Perman Amelia Dubin Lyra Davies Neave Scott Tom Shaw Edie Michael Noah Rouse Fox White

Here’s a Joke: The Shape-Shifters Edinburgh mangiare Seeking Whilst mulling in the bath aphelion pokarekare ana errands Summers in Sagae, Japan Obama in the Fruit Aisle When Undertaking a challenge The Soviet Music Machine Cavity Lost Inside the White House bins To a woman, in a gallery weeping women An uninvited Guest Cactus my uncle’s soul lies in the burrow of a white hare Shame Peter Pan Grows Up excavation / love letter Carpe Noctem Toby Sowing (Bullets) Holding Quietness

95 96 98 99 100 102 103 104 105 106 109 111 112 114 115 116 117 119 120 121 123 126 127 131 134 135 137 138 139

Jessica Warren Mukahang Limbu Madeleine Song Gaia Harper Charlie Peng

The Sea The Cleaners 2 Open Letter to Peter Walsh (I looked for you in everything) I Feel At Home When The Empty Falls Into Me How I feel

Foyle Young Poets of the Year 2018 The Poetry Society, The Foyle Foundation Young writers and The Poetry Society Schools and The Poetry Society Enter the Foyle Young Poets of the Year Award 2019 Access and nominate your teacher

140 141 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 151

Introduction “Our young poets forced their way into the final 100 through the sheer vigour of the voice.” – Daljit Nagra, Judge 2018 Welcome to the winners’ anthology for the Foyle Young Poets of the Year Award 2018. Since 1998, the award has been finding, celebrating and supporting the very best young poets from around the world. Founded by The Poetry Society, the award has been supported by the Foyle Foundation since 2001 and is firmly established as the key competition for young poets aged between 11 and 17 years. This year we received nearly 11,000 poems from nearly 6,000 young poets from across the UK and around the world. Writers from 83 countries entered the competition, from as far afield as Sri Lanka, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay and Malaysia, and most postcode areas in the UK. From these poems this year’s judges, Daljit Nagra and Caroline Bird, selected 100 winners, made up of 15 top poets and 85 commended poets. The competition’s scale and global reach shows what an achievement it is to be selected as one of our winners. This anthology features poems by the top 15 winners of the Foyle Young Poets of the Year Award 2018 and celebrates the names of the 85 commended poets (whose work is available in an online anthology, see p. 35). Judge Daljit Nagra says: “I was impressed by the maturity of the work we read; so many of our young poets showed a keen awareness of serious issues such as identity politics, environment issues and the global tensions currently between nation

7

states. I really felt our young poets were keen to explore the perilous state of our world through poetry; they seem to regard verse as a valid form of expression for serious ideas.” We hope the quality of writing will inspire even more young people to enter our competition in the future. All 100 winners of the Foyle Young Poets of the Year Award receive a range of brilliant prizes, including a year’s youth membership of The Poetry Society and an array of books donated by our generous supporters. The Poetry Society continues to support winners throughout their careers, providing publication, performance and development opportunities, and access to a paid internship programme. The top 15 poets are also invited to attend a week’s writing course at the Arvon residential centre The Hurst, in Shropshire. There they spend a week with experienced tutors focussing on improving their poetry and establishing a community of writers. Alongside the prize, the Foyle Young Poets of the Year Award programme includes a range of initiatives to encourage and enable young writers, both in school and independently. We distribute free teaching resources to every secondary school in the UK, share tips from talented teachers and arrange poet-led workshops in areas of low engagement. Each year we identify ‘Teacher Trailblazers’, who share best practice in creative writing teaching. We also commission Foyle winners to create features and challenges for The Poetry Society’s online platform Young Poets Network. Through this work we continue to support young poets everywhere, so that there is more outstanding poetry to celebrate each year.

8

Since it began, the award has kickstarted the careers of some of the most exciting poetic voices. Here are just a few of this year’s successes by former Foyle Young Poets: Jay Bernard won the Ted Hughes Award for New Work in Poetry and announced their debut collection with Chatto & Windus; Phoebe Power’s debut Shrines of Upper Austria won the Forward Prize for Best First Collection and was shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize; Jade Cuttle was appointed as the new Contributing Editor at Write Out Loud and won the Saboteur Award for Best Reviewer of Literature as well as a Creative Future Literary Award; Margot Armbruster’s poem ‘Husk’ was chosen as a Guardian Poem of the Week; and Annie Katchinska won an Eric Gregory Award. Finally, as we reflect on our celebrations of 20 years of Foyle Young Poets in 2018, we offer huge thanks to the Foyle Foundation for supporting our anniversary programme of events and activities. We are grateful for the generous support of everyone who has contributed in some way to the celebration and look forward to marking many more such anniversaries with you in future.

9

Eira Murphy Endings My father told me a love story the night before he splintered and we picked bits of him out of our hands. The love story was a long one. He held it over my chest and let it weep over me, let the ache spread across my lungs. He told it from memory. • When we were little and the sky was wide, before the limits of anything he held me up and I felt like a second thought or the remembrance of something whole. • The love story began with the sounds of your stomach and me dancing wild and red, the reflection of a painting, broken glass and the sound of rain threaded through my hair. The goldfish died and came up covered in white gold floating with one eye open

10

letting in the watery light of the garden and the recorded bird song you played over coffee. You told it to me through the bannisters, bottled it up in the green paint that flaked off in swollen sighs. Endings that come slowly and break open over our fingers. Once upon a time, a girl came to a castle with wet hair dripping brown ink down the front of her throat in great smudges. The castle doors were golden and closed and the rain sent brass shivers over the girl with wet hair. A second ending. A long time ago, a princess swept through the night. Her hair was the colour of white heat and it burnt the sight from her eyes. All this happened. More or less. The woman found the love story curled up in the palm of her husband, pink ink the colour of his tongue bled over his wrists,

11

formed miniature hearts at the base of his pulse. Once upon a time, a man was looking for something in the dark. He felt the shape of it, hard and small above his ear. The girl came to the house with open gates. The rain fell about her and her throat was broken open by the strength of the light and the golden eyes of the man who was searching for something already stitched into him.

12

Matilda Houston-Brown Starting with bees Our beehives are empty, leaning against the side of the barn, battered, exposed, fetched to rest sleepily, slumped against other things, retreating slightly with half shut eyes and peeling paint, layered in toppled squatness, pushed with sticky edges and well used, unsanded layers, worn down by a humdrum of a million previous beating wings. They look abandoned, but are simply second-hand, brought back because my dad has always wanted bees. And inside, off-white ghosts are rolled and packed away, put up with the smoker (slightly rusted with past use) between spare nails in empty paint pots, and hammers and Quality Street boxes filled with bits and bobs that will always stay right there, rattling in the dark. Under our feet, grass has died with the sun’s weight on its shoulders, fried, burnt like toast, folded at browning edges, re-used, like our sick dog that sits by my mother on the garden bench, tucked into her lap, while the other dog runs, barkbarkbarking at the hot dusk.

13

Benjamin Waterer Rhyme Disease I went to see my doctor, Mrs Lollipop-Smith, on Monday, But she spoke to me in rhyme – she said to come back Sunday. She said to me (through a crack, I believe, in her glistening surgery door), To go away, she cried and wailed, it really was a bore. A rhyming tick had bitten her, a bad, bad case indeed, She had to stem the flow, she said, or words would start to bleed. I then picked up a leaflet that told me what’s going on, Rhyme Disease is caused by ticks, fifteen inches long, After they attack, it said, there is no hope for you, Now for all time you’ll speak in rhyme and not know what to do. The first case was found, it said, Rhyme Legis, by the sea, The unfortunate man was stung by a tick, disguised as a bumbling bee. The victim, nineteen, spoke only in rhyme for the rest of his terrible life, With five hundred and forty-six children and a hundred and eighty-nine wives. The cure, I found, for Rhyme Disease, was really rather disgusting, To swallow a black leather armchair after fourteen hours of dusting. So to say it, I think, is a matter of ease, Never, ever get Rhyme Disease. I’ll say it again – it’s a matter of ease, Never, ever, get Rhyme Disease.

14

Lai Ling Berthoud Rodger Rodger lived under our dining room table he was my older brother’s friend I snuck brief glances at him, bending down to tie up a shoe lace I used to feed him candy, slid hastily across the polished floor appearance distorted in sparking reflections He lay among the piles of shiny wrappers of toffee and caramel. I stared at his big lipped, toothy smile peering up at me as I chewed boiled carrots and mashed potatoes. I always worried if he had enough space his bony knees tucked into his withered chest His ragged breathing interrupted every meal His skeleton hands outstretched towards my leg his fingers danced up and down my calves whenever I looked down he vanished into the corner of the table blending into the rough wooden pattern or hid between my brother’s legs “He doesn’t want to see you” my brother would say I never got too close As I grew older Rodger started to disappear I saw his toes begin vanishing into our scratched wooden panelling His grasping hands merged into the dust collecting under the table If I watched closely enough I could see his arms fading away I fed him biscuits with a sense of urgency smuggled under my jumpers from our guarded pantry Imagining his sunken face He would grin at me leaving crumbs spelling out crude messages I came home from school one summer evening

15

My feet were damp and sticky under the dining room table I glanced down Rodger had disappeared into the cracks in the floor “Where did he go?” I asked my brother “Don’t be stupid, he was never really there”

16

Sophie Shanahan Purpled The thumbprints beneath his eyes do not fade. He sleeps for hours, weeks, days but there they stay. As if the thoughts behind his brow are seeping out. Somehow he feels them soaking through his skin. He drags his bruised self away from hot sheets. In sleep he cannot keep the secrets in. Instead they rattle every slight whisper of breath. And battle his fingers into fists. So he wakes with damp clothes and nail shaped scars. At last he is free to suppress his purpled self. Is able to wade through templated exchanges. Aching through tungsten-lit days. Eyes prick as for once he ventures outside. With pills and smiles he drifts towards the greying sun.

17

Linnet Drury Geography We were meant to get hard data but our experiment was eaten. A seagull. Picked it out of the water then took it to a groyne. Rap tap tapped it in half. Our apple. Two red cheeks ripped apart like a confession of miscomprehension. We would never record the rate of flow of longshore drift. Our boots spent the uneaten hours building up a collection of bitty stones and sand to walk home in.

18

Domi Pila Me and Dion In the beginning there was me and Dion in the neon lights of an ice-cream van on Venus, it was night time and dark spilt like a warm milkshake onto both of us. Rising from our beds – his in the main body of the ship, mine near the pipes in the basement. We slipped away and met at mad Jerry’s red truck café that greeted each moon with a jangle. No air pumps out here in the scrubs. It was quiet. The sky was so heavy it almost wept, we fumbled for silver-dashed coins in our pockets – each one had a galaxy emblazoned – three for mint chocolate chip. And then it was me and Dion on rickety metal chairs in the neon lights of an ice-cream van, we’d been talking about gods and why you couldn’t see them like you could see the lighthouse in the distance. We sat beneath fumes from Jerry’s cigarette, and tinny Italian tunes from the radio. Dion closed his eyes, I held him and watched flies swarm round empty syrup pots.

19

Maya Williams-Hamm Side Effects Within a week the side effects took hold His limbs grew heavy and swollen with the chemicals that kept him alive And sometimes he would tug at the stretched fabric of his clothing wishing for other ways to say I’m bursting at the seams

20

Meredith Le MaÎtre The Oceans They Crossed I wish for the strength of my ancestors, their shoulders rippling broad enough to carry the weight of the earth, skin darker than the molasses they boiled, day in day out til pitch dusk, when they couldn’t sleep quiet for fear that wandering hands would pluck them like mangoes; cos the masters thought they owned their every atom even their stardust souls. You say our hips are too wide, our legs thick like palm tree trunks, but have you ever seen such power? That walked straight outta captivity into a world purple with nightshade and blossoming bruises. My grandmamas were queens, who worked their fingers to skin and bone so that my horizons could be vaster than the oceans they crossed, so my Afro could take up more space than I do,

21

and my future could brim with a million galaxies; and isn’t that the most beautiful thing you’ve ever heard?

22

Ginny Darke Marcia From The Amalfi Coast Every bird was a blemish in the sky in the clove scented wind then. I thought about peaches and apricots and satsumas and her fingers against my neck, and the tendency of the metal cage on the porch to swing with no direction. I closed my eyes and wished that I could have done that too. I only think about it now because she was a good kisser, blooming against my mouth like sweet pink, tinged nectar. In a few past lives, this must have been enough, the place. Molten hands in my hair melting at the roots and the swift rush of her body like the atlantic, coming in cold. Every body of water was thick with salt and the summer was the image of medusa as a child.

23

Noah Morrison The grandfather clock The grandfather clock is a monkey. It swings around the tree-top. Gliding to the rhythm, The moving never stops. The grandfather clock is a chameleon. He looks three-sixty degrees. He looks in opposite directions, He flicks like one-thousand fleas. The grandfather clock is an automaton. All of the gears mesh. He cartwheels and spins, Inside his wooden flesh. The grandfather clock is a dolphin. He jeers and whines and clicks. Although there is some silence Between his tocks and ticks. The grandfather clock is a friend. He welcomes you into your home. He only reassures, He’s never made a moan. The grandfather clock is a mystery. Forever has it been yours? Why does it need winding up? And where’s its power source? 24

Cosima Deetman Tongue John was a man who, while drinking camomile tea, burnt his tongue so severely that paracetamol was insufficient, prompting a visit to hospital (which he regrettably associated with a rejection from med school); furthermore his tongue swelled to the size of a bell pepper, a pepper with limited functionality, so John would soon discover while attempting to explain his predicament to an unsympathetic receptionist (tentatively nodding but evidently confused) before taking a seat in the hospital waiting room, where John, his tongue now the size of a butternut squash, played Tetris in order to distract himself from the metallic taste, until 76 minutes later when a doctor called his name and gestured to an examination table on which John, unable to speak, lay in silence as the doctor examined his tongue before declaring, ‘I think you should go home, John.’ There was yet more silence. ‘Look,’ the doctor continued. ‘This is the sixth time I’ve seen you this week. It’s clear you have a problem, just... not one I can help you with.’ The doctor rifled through her bag and pulled out a mirror. John held it up to his face and saw a small, red ulcer on the side of the tongue, which, for the sixth time that week, wanted him silent.

25

Danique Bailey Tell me about plantain Tell me about plantain. The sizzle as it hits the pan Sweet aroma mixed with crackles As oil fizzles and splatters to create That golden brown. Tell me about plantain. The splash as it lands in soup Able to retain the fruitiness and soft Supple flesh that’s reached a ripeness not yet slimy But with a sweet tang. Tell me about plantain. The chips from the corner-shop Chopped in perfect circles that are Lightly seasoned and have that crunch For a tasty snack. Tell me about plantain, the way you cook it right, But don’t tell me how to pronounce it or There’ll be shouts of ‘mountain’ and ‘fountain’ Followed by retorts of ‘sustain’ and ‘complain’ Arguments about nouns and verbs Without a conclusion reached Oh! Tell me about plantain But never how to pronounce it Because, I’m sorry to inform you, For the whole poem, you’ve been pronouncing it Wrong. 26

Jazmine Brett The Treerific Amputree “My goodness” I said to it. “How on earth did you end up like that?” I was truly stumped. “You what?” The tree replied in a Scottish accent that sounded Scottish. “How did you become an amputree?” I asked. He tree sighed before replying “Just leaf me alone.” “Oak Kay” I replied. “Look” he said. “I’m sorry for snapping at you like that, but can we please stop the tree jokes?” “I’m sorry” I said. “I’m just a sap for tree jokes.” “It’s alright.” An awkward silence lingered before the tree broke it again. “You know what?” he said. “What?” I asked, intreeged. “I think.” He paused.

27

“What, what do you think? I’m intreeged.” “We have amazing chemistree.” “What do you mean?” I replied. “I think… I think I’m in love with you” the tree said. “You’re barking mad” I told him. “How did you end up as an amputree?” “Do you want me to tell you honestree?” the tree asked me. I nodded. “I’m not an amputree. I’m justa fat treenager.” “I’m gonna leaf ” I say walking away awkwardly. “Tree you later.”

28

Jasmine Woodcock Stars I used to study spilled ink on dead trees lit by canned candlelight, Framed by closed curtains and pink-painted plasterboard, Before I looked out, looked up, let in the moonlight, And learned the language of lights hanging over my head. Calling me, the earth cradled me, my eyes adjusting to the moonlight While the worlds inside the windows around me faded to black. As if a projector in my mind lit the sky, the picture book pages appeared.

29

Will Boagey Witness for the Defence So Tony, myself and his mate’s mate Dave (who ain’t gonna play the witness today At any rate On account of the fact That his gran’s running late to Saint Pete’s gate) hit the scene. And Hit it hard. Soon We were six shots short of a firearm store, hungry for more. Tony fetched round four but dealt with trouble On the dance floor. He spilt his drink on a mug with a pint. Got into a fight and Couldn’t get out. Turns out he was Joe King With Tim Week and Lee Once. And now this is where it All went a bit voodoo. Me and Lee began the Melee, but soon There was a queue. Week kneed Tony, suckered Once twice 30

and hurled into a bin. Joe King was choking and Duking with Dave Who was puking And soon, everything was Shambles. So I bounced out through the double double-doors and commandeered a car and Shanghaied Tony and burnt rubber. We tried to outrun them but with Dave’s backside sat In shotgun my only mirror was rear View. After eighty yards we made first base with a lamp post. After that slight hiccup The flashing blues and fluorescents Descended like fire flies To try and extinguish us (the flies on fire). And all the while I sat Stock still in flames. Like a lemon. Completely buffaloed, Your Honor. 31

Iris Gilbert The Office Tap, tap, tapping away. The odd conversation, laugh, cough or greeting. Slaving away but so happy to be there. I turn my head to see articles, emails or pictures flashing up. Cramp in my hands, talking to friends. I find myself watching people. The luscious smell of Scotch eggs and salad lingering next to me, making me feel more hunger than before. Though such a lively atmosphere, I feel the tension, the level of boredom in the room. Piles and piles of books next to me. I take a sip of my water and look over at the TV screen, flashing devastating news behind me. I look round to see the vast arrangement of stuff on fellow office workers’ desks. A Pikachu balloon, a half empty box of Earl Grey fudge, a mini bottle of champagne. I look back to my desk. All my hard work. In the office.

32

Hayden O’Rourke Terms and Conditions Protecting people’s privacy That’s our priority here at [REDACTED] We saw you looking for a new phone A delightful phone at that, pre-owned of course! Delightful telephone number, exquisite Address, account number and acute taste in Television soaps. Sarah poked you. Would you like a cookie? Protecting people’s privacy, it’s how We designed our system, what’s your favourite Date of birth by the way? We see you enjoy Candy Crush, how about Farmville? Dragon City? National insurance number? Katie poked you. Have you been to Asda recently? [REDACTED] allows you to communicate to every country On earth anytime, as long as we know where you are Anytime. It’s only fair. Have you read and agreed to our terms and conditions? (Side effects may include nausea, paranoia and Technophobia) What’s technophobia you Ask? It’s Latin for ‘fear of craft’, I’m sure you’d know this Your mother’s half cousin is Greek after all. Zuckerberg poked you. Here at [REDACTED] we prioritise our pigs’ privacy Rather than advertisement revenue. Seuss poked you.

33

Lear poked you. Zuckerberg stroked you. Put the phone down my Wife says, I fancy a trip to Asda.

34

Ella Christian-Sims 4, 5, 6, There’s my Grandad and the smaller sadder grandad inside him. Tomorrow he will tell his daughter she’s a disappointment and then tell his friends how proud he is over 4, 5, 6 pints. But for now he is sleeping with his eyes wide open. His hearing aid is on the table beside him, because he doesn’t like to hear his own footsteps, or the crinkle of no one next to him, or a ladybird flapping his wings. Tomorrow he will make curry for breakfast because he hasn’t learnt anything else. He will sit at home because no one can drive him to 4,5,6 pubs a day like they used to. The woman he propositioned will walk past with her husband and he will miss his wife. He will sit in that chair in the morning, because the light from the window helps him read. In the evening he will sit in that other chair with the light on because he can’t read anymore. For now he is sleeping wide awake, cursing his mother for making him breathe this way, and hoping tomorrow he can muster up eggs for breakfast.

35

Sofia Marliini Heikkonen my parents’ love: a revolution two lovers bend themselves backwards to ring around each other in a promise but after 21 years, their spines start to snap, their wrinkles crack open, their skin curls itself back down their body – until all there is left is their bare flesh and fresh bad blood. it is a monday morning and I am eating cereal as I see two skeletons create crossroads of our living room their bones clanking like wineglasses held by drunken hands at 8am, yet they have always loved with such sobriety hearts already dropped onto the parquet, bouncing around like a kid forgotten at the trampoline like two fat old toads over rain-weathered lily pads in the heat of a sunny evening – and I try to think of a sunny evening here try to reminisce of a time when both my parents could walk side by side, without having to take each other in their stride because even when they held hands they met at perpendiculars, crossed the other like they always do, but also like how their paths did over two decades ago

36

somehow some gravity had pulled them close from corners of this globe so apart you’d call it ambitious to try to tie two continents together with a ring and a baby – and maybe love like this can indeed only transcend so far, maybe this little red dot had only been a location-pin drop and never a home, maybe there was just too much bending for their bodies to bear I grab my bag and leave for school I throw an “I love you!” to the two of them and hope that it is heavy enough to push the pendulum of this home to swing through another day

37

Naomi Rae Psychosis Questionnaire Are the songs on the radio written by my high school crush in an attempt to save my life? Have I just killed this banana by squeezing it too tight? Is my Dad trying to abduct me? Am I the lone survivor of a rare strain of Spanish flu returning after one hundred years? Have I overdosed on Lemsip? Is the film crew in my house arriving on helicopters? Has an American prank show called the BBC who are posting videos online, of me trying to sleep? Does the cameraman on the landing have black-rimmed glasses and curly blond hair? Is a group of paramedics following me everywhere? Am I going to hell for eating tuna steaks? Is my head inflating like a balloon? The smell of burning in the night – will it stop me ripping the infected sheets

38

into strips? Are the birds circling around my head connecting to my spirit as I stand in the kitchen? Can’t you see how skinny I am? Is this doctor going to hit me? It all makes a lot more sense when you have counted the cars and people walking past. Does everybody know?

39

Chloe Chuck Flower Pressing with Weeds I lie, an unclean rib in her cotton palace her perfume dull and flat on my wrist the tv blares in blurs background noise she taps her nails on the handle of the butter knife can you stop that? she clicks her tongue her lips move like free verse your mouth she says your mouth is all metal and good intentions she is a cruel decay and I cannot help but adore her pulling my stray hairs like weeds a scavenger but I don’t mind being prey I’m a bad meat luckily, she doesn’t have very good taste a biro nib scrapes blood from beneath her fingernails that’s disgusting, I love it I write tragic poetry with that pen but it’s hers now even though it’s mine it’s hers everything she touches bows to her has raw scarlet knees for her

40

my body is a DIY shrine to her she’s neither pure nor good she calls me roadkill “the type you want to take home and taxidermy” she laughs crookedly the runt of the sunflower litter she hates me I love it

41

Rebecca Huang Barnyard Elegy When winter beat her way through the thatched hat of their naked den Momma found them scrapped on the barn floor their tangled limbs were commas and apostrophes pinned onto her wordless horror the imprints of slaughtered hooves call to their sleepy eyes pillowed by death but it’s not so bad, they choke through their anhydrous lips – johnny lost a finger to frostbite but lucky he had extras georgie lost a toe we used it to play tic tac sam lost her will to live you never really liked her anyway georgie takes up too much room he’s on my side of the floor – i knew you’d rat me out you baby – and lily can’t stop crying it’s worse than her singing charlie said he’s sorry he ate my last candy bar i told him it’s okay i don’t think he’s sorry anyway cindy wants us to shut up so she can die in peace johnny said go to hell cindy said too bad we’re there Momma says nothing

42

Aisha Mango Borja Learning Difficulty Times I felt like a blackberry bush, sitting in the corner hiding blue brains darker than bruises. Times I taught myself to be content with being alone, myself my own crutch. Times spent smelling pink and blue words. I remember talking to the dark. I don’t remember the bookshelves anymore, but I feel the crates of ordered pages standing upright like soldiers. In the place I wasn’t allowed to go were the things I really needed, the slug pellets to keep Albatrosses away from the primroses. I’m recalling me pushing my hair back with my glasses that sat on my head like a robin, us both out of place.

43

Morgan Rhys Sker Beach There is nothing here but the sea and the trees and they thrash about as loud as a jet taking off. Dust on the rocks, on my face, I brush a stone with my hands and find a fossil. A piece of an ammonite, a circle as old as space. There’s a storm coming in. I can see a darkness shifting over.

44

Katherine Spencer-Davis Odysseus and Penelope people say there is something strange about him, the boy who seems to live inside his head. (they’re not quite sure what it is, exactly, but there is something different about him. something that sets them on edge, like he’s a bad omen, a harbinger of doom. they do not say much, when it comes to him, but they all agree that he must be something else. something other. something not quite like them.) people say he is a mystery, that boy, and they do not say anything else. // it begins with a dream. he kneels in front of a man hidden in shadows. there is nothing but darkness surrounding him, screaming with the voices of ghosts he can no longer remember.

45

it will cost you, the man says. it echoes, bouncing against walls he cannot see. I will pay the price, he vows; the ground trembles beneath him. there is a ringing in his ears. (something is different, when he opens his eyes. something has changed.) // it is spring, the first time he dreams of her. she is beautiful, and she is not; there is beauty, yes, but it is like the way a sword feels perfect in his hands, like the taste of victory on his lips, like the way the stars sing even when there is no one to listen. it is a silent kind of beauty. (limitless.)

46

there is fire in her, too much to be folded into language. (she is something else. something more. he does not yet know what it means.) // she is everywhere, after that. she taunts him, tugging at the edges of his vision and disappearing as soon as he looks too closely. (he finds a girl staring at him, one of the times he follows her; her eyes are harsh, but they are lit with flame, and he knows. knows. has seen those eyes before. a name comes to him, then, a whisper, a sliver of fate he should not know. penelope. it sounds like fire.)

47

// he dreams of athene later, in summer. (he is old, can feel the pain of it heavy in his bones, and she asks for things he cannot give, anymore. you are a hero. you obey the will of the gods. he is not, has never been, will never be. the gods have always taken the things they should not receive, and so athene takes. he has no choice but to give.) athene is the girls who are not penelope, the girls with kindness in one hand and a knife in the other, the girls who do not challenge him but remind him that they could, all the same.

48

athene tires him. (he has yet to find penelope.) // he is not prepared for war. (he remembers ghosts clinging to a man in shadow, and he feels their deaths, feels the satisfaction of sending them to hades. he remembers lives lost under his command, lives he could have saved; he remembers mourning, too many graves and too many tears. the night he dreams of the cyclops he wakes up screaming, fear in his lungs and blood spilled across his hands.) // somehow his dreams bleed into the rest of his existence.

49

he is angry, and reaches for a sword he is not carrying, a sword that does not exist. (the rage dissipates immediately; he is shaking, needing a fight or a drink or penelope, needing to be something other than strange and different and a killer. the next time he dreams of penelope, he asks her who he is, who he is meant to be.) // she does not answer for a long time. and then – odysseus. it is soft, gentle, laced with sadness and regret; her light has dimmed, and she refuses to look at him. come home, she whispers, cupping his face in her hands, and something in him breaks.

50

(he wakes before the sun, tears slowly running down his cheeks, a hatred beginning to burn his insides. odysseus, he thinks. it feels strange, heavy in his mind. he thinks of her face, pain stamped across her delicate features as she begs him to return. odysseus. the earth shifts; he is more than he has ever wanted to be.) // athene finds him a day later, requesting his help for something he forgets to listen to, and in return she guides him home. (she wants him to kill a man who has wronged her. she reminds him of all the times she aided him, the time she fought his enemies at his side.

51

he thinks of the guilt that beats with his heart, blood on his hands that could not be washed away, and says no. says I am not who you think I am. the gods have always taken the things they should not receive. athene takes. he refuses to give.) the ground trembles beneath him. there is a voice, loud in his mind. it will cost you, hades tells him, years too late and just in time. name your price. somewhere in the distance he hears an owl screech. athene’s presence disappears. you are beyond the gods. hades says. they will not reach you.

52

he smiles. (the world is silent.) // (there are things that cannot be) he stands knee-deep in water, runs his fingers through it and feels its pulse beating steadily. this is the ocean he once ripped open and laid bare for the world to see, and in return it slipped into his bones and forced him out. he thinks of destiny. thinks of a name he no longer wants to bear. I am odysseus, son of laertes, but he is not, he is not, and yet all he sees is her mouth, the way it shapes around his name with complete conviction. (do not hide from fate. he turns, and the universe is below him, is beside him, is running through his veins.

53

he runs. the water clings to him, and it feels like her hands, like her voice when she begged him to stay. odysseus is water, is stardust, is destiny. he runs, and does not look back.)

54

Divya Mehrish Diseased They call it autoimmune As if it were natural, mechanical involuntary It sounds too cold. The first day I became a definition a stethoscope searched me As I sat beneath a white light, on top of tissue paper that could wrap a gift. What the doctors found was not mine. But I wouldn’t relinquish it. They didn’t know what to say but “ulcerative colitis”. A needle pricked my skin Pierced through the soft pastel sunrise of my arm – A forced aurora That was the first time. After months of extracting rubies, My mine was empty but scarred by jabs punctures screwdrivings of strangers with daggers strangers with daggers in white coats blue shoes squeaky clean who are just helping you, sweetie, by gifting me with a permanent fear of anything sharp. I was an ashen ghost in a wheelchair

55

My torso suddenly deemed too weak to hold the heart that thudded at the speed of lightning. But I had been calling it quits even before I started getting Play-Doh food on plastic trays. I think, somewhere far away, I had killed myself. The squeaky clean blue shoes white coats call it an it As if the disease were an entity of itself. As if I were just a vessel carrying this being, this God, In a pregnancy that etched its story Dozens of trimesters too deep. They told me to stop crying, so I tried biting the inside of my lip Instead. But now a raspberry smoothie is swirling inside my mouth and I can’t Swallow. Now they’ve started putting me to sleep during the day. A soft, thick powder kisses me goodnight and thin silver tubes tuck me in gently. That’s all it takes to get me to shut up. In those cold, humid moments before gloved fingers press My eyelids close, Adrenaline rushes through me like the gallons of freshly brewed wine Oozing out from the ulcers that grew like my dark, tangled hair. What they don’t know is that there is so much they don’t know. I am not a mystery. I am not their culprit.

56

I am a child whose tears run down the lining of her colon, not her cheeks. What they don’t know Is that my body isn’t attacking itself. That my white blood cells aren’t butchers. That I don’t want to die. What they don’t know Is that there is a puppeteer Who has made a stage of my colon who puts on shows whenever suits him best. He doesn’t know he’s supposed to ask me first. What they don’t know Is that his loud music and the trills In his singsong voice Aren’t deafening. What they don’t know Is that the convulsions in his booming laughter that even the blood hurts Less than being locked up in a little grey room that tastes like Febreze. Less than being excavated. Less than being called diseased. What they don’t know is that in those molten, melting moments after they press my eyelids close, I can still cry. I can still remember the times when my skin was soft and smooth when my greatest fear was heights

57

when I didn’t believe in bodies melting away like rain – when I was still a child. And I miss those times. So I let the flashbacks sing, as loud and clear as they need to, In the meat of my beautiful eyes. What they can’t know is that maybe, just maybe, the holes in my body aren’t gaps to be filled, but maybe they’re wishing wells, waiting for a little, thirsty face to peer down and just smile

58

Adriana Carter Self Portrait as a Dying Canary to fold a paper crane my mother and I first talk about ephemerality like a disease. stitch ourselves together with needle & thread recalling the time my mother sliced her finger open with a pin when trying to teach me to sew. but now in the evening, mother sits on my bed holding my head in her lap. untangles my hair. I try to pretend I am eight instead of seventeen & swallowing pills that taste like bullets. she tells me my skin is paper thin & I think maybe if my spine splits down the middle my wings will grow back. mother sings me a lullaby about her own childhood. tells me I don’t know what I’m talking about when I say my body has developed into the negative space of a photograph. but all I know is my hair collects at the bottom of the drain like molting feathers. that this bed has become

59

a nest I can’t leave. I clutch bedsheets in my fist, watch them curl around me like bougainvillea vines. thorns cutting into me, reminding me of mother’s sharp tongue so I try to hold pomegranate seeds in my mouth like a promise I can’t keep. in the morning I barter my larynx for a canary’s. I find a clipped wing on my nightstand.

60

Serena Lin beetlejuice Danny and I put up a valiant struggle against boredom fight off the long march of hollow July afternoons set up fishing poles on the lake take our crude time hooking up bait and untangling line we catch swim trunks, milk cartons, tap shoes, leather buckles, dull mirrors, an entire century of the New Yorker, unread on the lawn between the lake and the porch a junk city sprawls mosquitoes become fickle tenants dragonflies low-flying planes beetles busloads of tourists when the rain comes it collects in puddles and tire swings ants float by on plastic spoon barges Danny wakes up one morning with these long limbs comes down for breakfast and

61

smacks his head on the hallway light when he swings his too-long leg and topples an entire block I push him in the lake he is an unwitting Godzilla an easy villain he stays under for a troubling few seconds, no bubbles breaking the water’s surface, just the wake of his body lapping at reeds I am kicking off my rain boots when he sputters to the surface, a curse word in his gaping mouth he doesn’t tattle but Ma still gets mad says the city has to go I become a one-girl picket line planted in front of the city, hold a one-girl die-in in which I lie moaning on the porch, organize a one-girl march where I walk in circles around the lake singing Itsy Bitsy Spider the demolition comes anyways Ma fills a trash bag with the city wearing gardening gloves dismantling without regard for the many-legged

62

inhabitants movie theaters and supermarkets fit neatly into curbside bins I refuse to come in for dinner, floating belly up on the lake, letting the current spin me from one side to the other waiting for tomorrow, the sun will set a little earlier summer’s hold will loosen just faintly, jostled by impending twilight

63

Lizzie Freestone on the woman we found at the beach we were 8 & she was whatever age corpses are. nameless, splayed, empty skin on cold sand. [i remember that first moment. the hush & the roar. our small footprints pressed through thin tides.] she is remembered in fragments: [i dream of her still] look, here, a foot, dainty toenails, yellowing & pink-chipped, old-manicured [i wonder, did she dream?] look, a hand, signet ring on a little finger swollen almost to burst, like ripe fruit or the waiting dam. amber on silver on dead white-purple. [what did she dream of?] here, fingers curled skyward, covered in sores too old to weep [& then after – how you gripped my hand & said nothing, as children do.] here is a nose and a mouth and two empty eyes [i still see the dirt in them, the salt crystals starting to form] here, hair, a tangled net for old plastic.

64

we found her alone; we found her together [i wish i knew you dream of her, still as only the dead are.] & we did not know her name. [i like to think she is dreaming.]

65

Evie Collins Starting The Day The Right Way If the night sky were a champagne bottle, and the morning the lustrous froth it spills over the land at the pulling of a cork, maybe, just maybe, the dawning of a new day would be more celebrated and not a trip to Hell orchestrated by alarms and gone-off milk and unreliable public transport.

66

Sarah Feng the good brothers The clock is as sharp as blood, its minute hand peeling like a brittle peso from my throat. Dalí should be here, I said, but nobody was there any longer to listen. I tried to unstitch myself from the hours, but instead they yawned. Thrashing wild in the bleached bone of your repentance. All the good brothers know that this is how it works. The only thing that will make me soft, I said. Gaudí’s trencadís above us starting to shake. I couldn’t move without lead minutes slicing into my stomach. You spilled out of me like oil and tanqueray. The good brothers crouched under butter-yellow eaves & struck matches against the hooks in their mouths.

67

Maia Siegel A Bottle of Zoloft Wins ‘Never Have I Ever’ One of us is turning fifteen, and we are celebrating in the attic, accumulating empty yellow Butterfinger wrappers and one girl with dyed-red hair is drinking a soda with a label all in Russian and we play clockwise games in which we try to hide our love of others’ secrets. The birthday girl, blonde with dark blue acetate glasses, gets up and tosses a clear bottle of paste pills into our circle of cellophane sleeping bags. She says that she was saving them up to kill herself, and now my secrets, that real bad dream I had once, those days I skipped dinner; they are worth nothing this round. I grab the pill bottle. I say that we should flush them. Now, we should flush them now. She doesn’t want to. She waves the idea away and someone says that they’ve been kissed three times and my attention moves from the bottle on the beige carpeted floor to their lips and how three kisses landed on that particular pink-skinned space. The next morning I have oatmeal for breakfast and when I open the door the cat runs out and I leave. I remember only later that the pills

68

are still on the floor, next to the brown-streaked Butterfinger wrappers and curved Russian soda bottle, silent and chalky and maybe celebrating a little, the winners of the very last round.

69

Niamh O’Toole-Mackridge Pride, 7/7/2018 And maybe it’s the sun casting the London buildings golden that makes me feel this way, or maybe it’s the giggle induced haze I settle into as we wait for our train whilst sitting in the middle of the closed off road. Or perhaps it’s the smiling, joy filled people in any and every direction, making their own way home as the sun sets. But maybe (just maybe), it’s because I feel so safe yet so freed simultaneously, a combination I have never had the serenity to experience before: and it’s strange, it’s new. But as we pick up our sun-cream and flag filled backpacks to wave the gold tinted windows goodbye, I can’t help but want this feeling to last forever

70

Alexis Venzon The Letter my finger traces the edges of the withered paper rounding at the corner as it pricks into my skin as a sphere of blood emerges glistening in the candlelight and diffusing in the stained paper his voice lingers in the words he hand wrote under the moonlight as he sings a sweet symphony until I fall asleep.

71

Samara Bolton Volcanic Father Father, When I was 11, my therapist told me that you were a volcano; that you just erupted, and I was simply the only person unlucky enough to be caught in your wake. She then drew a diagram of you resembling one: the pen moving over the paper depicted your anger overflowing as lava and a stick-figure me at the bottom, waiting for the magma to hit. When your words sent me to therapy, I would sit for hours and wonder what was wrong with me. When your actions scarred my childhood, I would blame myself for being the reason our family had been broken apart so early. She told me that you were a volcano; so, I avoided every orange beanbag because it looked like the lava you spilled and scalded me with, I avoided every crack in the sidewalk because I was afraid if I stepped on one then I would encourage my bad luck and you would erupt again, I avoided every confrontation with you just so I could distance myself from the reality that I had been forced into so prematurely. She told me you were a volcano; that your lava had burned me but given time those burns would be healed. It’s been six years, and although I have hidden, nursed and bandaged

72

these wounds they are still blistering as if I have decided to roll in your magma anger again and again. She drew my volcanic father in pen, handing it to me as if it were a metaphor dictating that I couldn’t erase the past: I couldn’t change you. But I wanted to. I found the letter that I wrote to you the day after that session, the diagram of your bipolar brain mapped out in pencil, and underneath it scrawled “are you really a volcano?”. I never sent it, but I’m sure that if I did I was hoping you would erase the lava, turn the volcano into a mountain and save the stick-figure me from getting scalded with your anger. She told me that you were a volcano; and one of the only things I remember from therapy was how to draw you: not as my father, but as a metaphor. I still don’t remember her name; I don’t remember the view from the window; the posters on the wall – even though I attended hours of sessions in that room. I remember that – I remember that I spent hours trying to repair the hole that you had burned in my paper heart. She told me that you were a volcano, and I still refuse to draw you in pen hoping that one day, you will show me differently.

73

Cleo Martin-Evans A conversation with myself written in Melanin [(1)missed calls] [Dial (222) to call back] [Brrr….Brrr….Br-] HelI’ve done something terrible – I’ve committed a felony. Have you? No. Yes. I don’t think you have. I have. I must have. It’s the only explanation – You haven’t – I’ve been condemned to eternal damnation – done anything wrong. Then I’ve done something not right – I just ruled that out. Are you sure – Yes. – that there’s not even a slight – There isn’t. Fine. Fine. [...] [...] Then why did they – You know this I’m sure I don’t. I’m sure you do. Think hard.

74

[...] [...] It’s because I’m. It’s my teeth. [...] What? What? What did you say? My teeth. They’re crooked. No, before that – you started to say something else – I should have got braces. You don’t need them. It’s not your teeth. Of course it – – isn’t. Of course it isn’t. There’s nothing wrong with your teeth. There must be, if people are – No. It’s something else, and you know it. [...] I knew it. Hm? It’s just me, isn’t it? Like, my personality. I’m too loud, always have been – dammit. I keep telling myself that I’ll work it out as I get older but it’s just not happening. I can’t ever seem to shut up. I’m too noisy. Right? I’m noisy, aren’t I? [...] Yeah? [sigh] You’re not a noisy person – Liar – – you’re a brown skin. [...]

75

There’s always gonna be idiots who care more about that than whatever else – and that will hurt you more than anything; but you have gotta stop playing oblivious. You are fully deserving of equal rights and treatment, but you can’t begin to fight and campaign against segregation and behaviour you refuse to acknowledge. You can’t keep pretending you don’t know what’s going on; I don’t care how much the truth hurts your feelings, face up to it and then fight for yourself – for others. [...] [...] [...] [...] H-hello? [...] [Call Ended] [(1)New message] I’ll talk to mum about getting braces. That should fix this. [Message Deleted] For the last time, it’s not about your bloody teeth. I suppose they are a bit crooked.

76

Rory Lewis If Only I Had Known Folded neatly into her rusty-brown chair, With antimacassar and velvet wings, Her leather handbag with the golden clasp, Stuffed with banknotes no longer current. The piano class picture propped on the sideboard, Faded mottled sepia cannot diminish Those spirited, striking eyes, The long blonde waves that none of us have, And the bulb button nose that some of us do. The matching hairbrush set by the mirror, Furniture pushed against the walls, Crisp white sheets, hotel taut, Save the almost imperceptible indent On the pillow. The mahogany display case with the etched glasses, “Only to be used for best�. And the china tortoise with the removable shell, For buttons and paperclips, And now a wedding ring. If only I had known that the sun-warmed tomatoes, On their tin plate tray With the chipped corners and the punched-out frill, Would not ripen for her this year. And only now, As I crumple packing paper Around the little brown teapot That always looked too small,

77

But never was, Do I silently let the tears flow, And drip onto the cardboard.

78

Madeleine Ridout Another Reminiscence So another time, We were driving back from Köln; I remember it as clearly as the lilting refrain of some ruby-crested robins Who clustered on the fence, And the snow stained scarlet like the velvet on my hat – Oh, sorry. As I was saying; We were driving back from Köln when we happened upon An empty house. The horseless stables sagged in the wind And the forgotten fireplace’s dying coals still throbbed a raw and sticky smoulder Like an infected gunshot. Smashed windows and unpacked bags sighed a reckless haste; Sets of shoes scattered like lost dolls And a jam jar of wilted flowers whispered of a recently kindled silence. An impromptu rumble of shell-fire cracked and the house shuddered, Bricks and beams crumpled; drain pipes Snapped And fractured disorderly. Mein Herr and I, too, left in a reckless haste, Escaping the buckling building At the last second. As we rushed for the car, A gust of yelping wind snagged on my hat, Tugging my hair up, up with it: a free bird. It hovered in the air, waiting undetermined, And was gunned down a moment later.

79

Julia Zhou And everywhere, the relief The dog saw it first – bold headline in the propped-up paper, and so he wagged tagged over to the goldfish, and the goldfish swish told the little ant crawling on the bowl rim, and the little ant passed it down the crumb line, and the line like a telephone wire carried it outside to the earthworm, and the earthworm, in its dying breaths huffed in the mouth of the sparrow, and the sparrow harked to the sky, to tell. The first trees learned from fledglings who etch secrets into parchment bark, and the tingling jubilation spread from branch to trunk to root, and the root underground network ferried the message to neighboring trees, and now the whole acreage knew! The forest swath erupts in celebration, joy shot from a canon. And everywhere, the relief. Long-held breath released, and everywhere, the relief. If just for one day, the relief.

80

Naomi Tomlin Rhubarb I often have a dream where your callused hands rip the wings from sparrows while I sit on a tire swing and watch the blood spray onto your face. You don’t wipe it away. Rhubarb grows in the empty lot between my house and yours. The stems taste sweet, you told me, but the leaves are poison. You said that someday, we’d have to look the fox in the eye as we slit its throat, and someday, you’d have to cut off a foot to save the leg. You gestured to the birches as you said that. It was fall and their leaves were fragile and translucent, like the spotted back of an old woman’s hand. Your mother was inside making lasagna and your father was in Amsterdam, running his hands across the softness of another woman and thinking that she was the most beautiful thing he’d ever seen. She was thinking about anything else – maybe how we are on a rock in constant motion and somehow not seasick. I was thinking about walking across the beach at low tide without the shells slicing into my feet, without the salt-thick sea stinging my cuts. You weren’t thinking about searing yourself into my brain

81

like a cattle prod into flesh or the echo of the sun onto my eyes after watching clouds for too long, but it happened anyway. You wouldn’t cut off my foot to save me anymore, but I still dream that, after you’ve mutilated the sparrows and the ravens and the canaries, you kill a rabbit and we eat it together, sharing our grandmothers’ stories until the mosquitoes are too dense and we have to run inside.

82

Cindy Kuang my small wife i had all of you, then some of you, then none of you and i turned to my nightstand, asked the photo of you what do you make of all of this? and your mouth wiggled and gaped and spoke yeah, sometimes it be that way so you learn that you shouldn’t wrong your wife or you shouldn’t wrong your wife even after she says it’s okay cause then she might die on you, leave you next to the mini picture of her minimized personality and you won’t know what floral wallpaper she’d hate or which shade of burgundy matches the coffee table, guests will laugh at the coasters and she won’t be there for you to hide behind, no one left to fake smile your way out you’d lie but really, all you wanted in life was a woman who’d laugh in the parlor and cry in the bedroom clutching magazines and saying show me, please, show me how to do like you, how to do it? and you got that, you did, but not the next part, no not the part where you rush in and hold her

83

Jessica Xu Departure My sister draws maps within the mud, traces her highways with sticks, roads like vessels, all carved within the Earth. She recreates herself as a landmark, a capital star. Morning dew catches on the tips of her hair, her eyes like darkened orbs. It is June now. The months have passed without a salve and her hair is still curling, withering to the ground. The hospital needles were never enough and I am still collecting the fallen blond, saving them for future’s memory. I have not loved her enough. Her years have passed through her in days, hollowed her bones, and drawn her closer to the opening of Earth. In this moment, I will reimagine her as starkly beautiful, without the frailness of her arms, the trembling of her lips. The sun rests its slow palms against the thinness of her skin and she is still unwavering in her fate. When the wind bids her to the place where I cannot follow, I will mark the Earth as the surface of her, as a landmark, strong and unbowing.

84

Beatrice Stewart Big Brother I hate that you got what you wanted: me lying on the floor for you, tongue out, like a bearskin rug. My lungs become moons, waxing and waning, whenever I think of you. Know that it is not often. I hope you’re happy where you are in your white-sanded island with your girl and your drinks and your guitar picks. I hope you’re so happy that you never come back to sunburns and rotting teeth. It is not often that I think of you, you of tongues and toenails, but when I do there’s a crumbling hole in me like the wall you punched. I am also your fist, your spitting mouth, the mustache you could never grow in. Like a lizard’s tail I am cut off from you.

85

Nandita Naik Mermaid Disease We caught her by the waves: incisors stained blue, cleaved scales caressing her tail. The ocean silent as a bluebell. Even the jewel bright crabs were motionless in their burrows. We swallowed our silver-tongued prayers and brought her back to the lab. We classified her at the lab. Species: Mermaid, or Once-Girl, or Something Lurking Beneath the Waves. When we locked her into an aquarium, she started praying, sewing herself to the glass until her scales sequined the floor like little moons. Her song burrowed through us, left us knowing the acrid taste of bluebells. Out of her sight, we invented myths. How her bluebellthroat sang with the dolphins. In all our labcoated glory, we told mermaid jokes over beer. Our boss, Mr. Burrows, kept tripping over his underbelly, waving at the test tubes covered in scales. He claimed the disease took his daughter, whispered a prayer. When her family identified her, we released our prayers, gave her up, returned to preserving bluebells. It did feel strange, somehow, to weigh her on a scale and not even know her name. Outside the lab the disease spread. More girls sprouting tails, diving beneath the waves. We pieced together scientific evidence, safe in our burrows. The mermaids drag themselves out of the sea, surround the lab, hands making burrows in the wet concrete. We lock the doors, whisper prayers for the honey-eyed children whose mothers were lost to the waves.

86

No one knew what caused the disease. We hoped bluebells could be the cure, but the captured mermaid never did speak to the lab. Her tears clouded the measurements on our scales. Slowly our eyes turned cold and scaly. Our wives didn’t know us anymore. We burrowed ourselves in work and bluebell-petals. The lab marinated in our skin, making its home among all these ruined prayers. At night we brought our daughters bluebells, which we clutched after they surrendered to the waves. Once in the lab, a tearful mermaid shed her scales. Waves in the sand feigned their burrows as we seeded our prayers in bluebells.

87

Megan Lunny The Nostalgist’s Guide to Naming the Lizard That Washes Up on Your Porch During the Flood When the lizard washes up on your porch like an omen during the flood, name it blue after the first time you ever saw the ocean and realized that most of the world occurs where you are not. When the lizard crawls up your toes and requests asylum, name it yes after your father, who asked your mother to marry him in the middle of a desert, where a single jackal howled at his proposal. When the lizard curls around your leg and your two skins become like envelopes, name it electric after the first kiss in a Pennsylvania storm, with raindrops the size of tongues over your back, and mosquito bites all down your thighs. When you pluck the lizard, writhing, from your body, to toss it back into the water lapping at your door, to be washed away like in Genesis, name the lizard nothing after the horizon that will inevitably swallow it, distant and indiscernible in the midst of all this trembling water, all this flood.

88

Corina Robinson Learning Masculinity I did not drown. In the toilet. That I was born on. Let’s start there. Sixteen years ago mom gave birth to me in our second floor bathroom, with dad debating whether to call 911, or get the camera. And despite popular belief, I wasn’t supposed to be born on the same thing you pee into. Although depending on who you ask I planned the whole thing. The miracle of life doesn’t wait nine months for the minivan to start up. Mom tells this story at every single birthday party I wish I didn’t invite my friends to, and I like to secretly think it’s for my dad. It took six father/daughter dances before I actually danced with him. The first five were a result of dad never learning how to be embarrassed, and seven year old me was in no mood to be stared at on the dance floor, but he was patient through each one. He teaches me how to drive and breathe at the same time. We listen to Grenade by Bruno Mars and he says “That song only counts if you’re talking about your brothers.” He thinks I shouldn’t be jumping in front of a train for anyone that hasn’t seen every side of me. My dad makes me give those weird, one-armed hugs to boys because they do have cooties. And he’s never been afraid to cry in front of me. Says concrete can bend, too, if you hug it tight enough.

89

I give thanks for my dad before a meal and bless each time he wakes up from a nap. He serenades me to sleep and, dad you know I love you, but you’re only kind of good at singing. He congratulates me on getting my first period and kisses the awkward out of my forehead before I can say “gross”. My dad delivered me on a toilet and didn’t faint at the smell, or the stretch. He smiled at the water slide of newborn skin and said “Baby girl, welcome home.” My dad works all day and still cooks dinner. Makes me a cup of tea when I’m up past 10:30 and says this is masculinity, watch it coil through my fingers. It was meant to be tender, don’t let any man tell you different.

90

Nia Bolland After the Visitation You slip from the see-saw, back into the same grey of cigarette smoke, back into bus stops and YouTube and designer shoes. This is what you called loneliness. I pick white flowers with green stems, half-dance home, cry in the shower. You do not butter toast for other people, or send letters, or dream about roses. You told me once – “You look like an angel.” You might not think about that now, but only now are you correct, in retrospect. I cry, like Jesus. You try to forget the differences between things but as always it makes your nose bleed. You take long baths. That makes you feel better for a little while. I swallow my words. After some hesitation I swallow yours too and that’s all I do swallow until I get used to waiting. Some people worry about me, because my heart hurts. But I am proud of that – a little superior, since yours doesn’t, these days. Might not for a while. Only your nose and your aching cigarette mind. This is my hubris. I am your God.

91

Gina Wiste Clockmaker in a Catholic school they tell you God made evil so we could see the good, as if good were no more than a collection of photons, dancing along the rods and cones until it makes something of an image. in the 17th century they said that God was a clockmaker who set the world in motion and then stepped back to watch an avalanche that he was powerless to stop, or perhaps didn’t care enough to. maybe this is why I feel my friend’s despair like a rock grinding at the base of my ribs, why tears are salt licks and sobs are wolf howls. because God is a spectator, just watching, and cinema is nothing without conflict. I know as well as she does that there’s a loneliness that cannot be described between the hands of a ticking clock. perhaps that’s where we fall in His plan, one step removed from tumbling amongst the gears and into oblivion.

92

Zoë Benton Mouthful of marbles it sounds like with every syllable a marble rolls out of her mouth a cold clacking whisper almost musical as if clipped vowels and clear words will get her through anything maybe they could if I listened maybe I would hear her but I seem to focus on her voice not what she’s saying on those clinking words gently clattering against each other and I wonder if those words will ever click against each other too hard and crack leaving her mouth full of sharp shards of glass ready to break whoever’s listening now I think about it it’s probably better I can’t hear a single word she says

93

Maya Berardi It’s June In Ohio And rain is summer simplifying itself & the shadows too are hiding in dry spaces & bugs pool near any hot body & a white van hiccups over a speed bump & every word spoken rises on its own pillar & stone knows it is royal & a bench sits empty in the soft palm of grass & off elsewhere a city slaps itself awake but now storm clouds knit themselves for rain & rain plinks with the cadence of a lullaby.

94

Sarah Zhou Here’s a Joke: Two men walk into a bar, only it wasn’t two men – it was you and my shadow, me and your hands, you and my foot caught in the door. You and me, on different planes; you and me, hanging from a ledge, fingertips slick with sweat. I think I tried to smile, but you just blew bubblegum in my face, the stickiness landing on my nose and staying there, like sunburnt skin. “I’m going to jump,” you said, but it wasn’t even a jump, not really. All you did was let go. First you were holding on to something, then you were holding on to nothing. I watched you all the way down, but you didn’t smile once. I don’t even know if you landed. Maybe you never fell in the first place.

95

Fiyinfoluwa Oladipo The Shape-Shifters When I was four, my mother took a knife and slashed it across my cheek. She laughs about it now, and uses the same knife to spread butter on my bread for breakfast. She said when I was four, she was thirty something, and so we were so young that we were justifiable to our actions. Therefore, she could not blame me when while she bathed and caressed my skin in the baby oil she uses for her thighs, I had accidentally shape-shifted. And I had transformed so quickly that my mother thought that my skin had been bleached pale white by the watery drips of oil that slowly rushed down my body. In a moment, my dark skin had lost its darkness and my irises flickered between brown and green a couple dozen times, before they landed on blue. Therefore I cannot blame her too when in half a moment, my mother had shape-shifted. From a woman who held a bar of soap trapped in a fishing net sponge, she became a woman holding a table knife, slicing through the anomaly, as if expecting that I would bleed the melanin that once covered my skin. Today, I am something-teen, and my mother is forty-eight – much wiser beings. We are so wise that if I should dare shape-shift from what I looked like yesterday into what I cannot look like tomorrow, she won’t grab a table knife.

96

Instead, she will threaten that she would grab the go-to-hell (scythe) from the storage room and slash at my other cheek – giving people a reason to stop asking why I have half of a pair of tribal marks on my left cheek. And it stops me from telling people that I inherited it from a dormant gene in my mother.

97

Amal Haddad Edinburgh Spring passes through our lungs and spits us out across an ocean. A finch blooms from my mouth and into the bonfire on your aunt’s farm, spliced into smoke, fossilized and seizing. Barreling through Old Town, clutching coat sleeves, choking up brandy and confessions from two months ago when I called you at 2 AM dizzy on the floor, unstitching myself from the history. Love feels like the time you put a plastic bag over your head and I was the only one who knew. But you can’t tell him and I don’t ask why when we cross the bridge to Princes Street. You say the castle looks like dripping piles of wet sand we watched fall between our fingers last summer, on that night we both watched the ocean after a hurricane and thought about walking in. Now we watch the plumes of what has been done to us catch the lamplight all finite and migratory, alive in the shifting quiet cadence of your eyes, in my feigned forgetting.

98

Zola Tatton mangiare eat in Italian eat, eat it up. The thought of it. The country that I haven’t yet met. Eat up the culture that I am hardly even a part of. Friendly faces along with my mangled pronunciation. choi proud joyful faces tu parli la nostra lingua you speak our language. But I don’t. Eat, eat it up, fill your mouth with pistachio ice cream and somewhere far away.

99

Elinor Bailey Seeking A new tenant for the empty room In the back of my head. Must not mind the useless facts Stacked against the walls or the Old memories on the shelves halfForgotten. Had to evict the old tenant after A drawn out uphill battle. He was A man in a suit and bowler hat who Kept saying that it was his home and Not mine and I almost believed Him. Room would suit someone who Doesn’t mind the silence rattling Through the rafters on a Sunday Or the occasional leak of anger When I miss the last train Home. Ideally someone who can Make an empty space their Own and who can fill in the gaps When I can no longer find the words Or thoughts or feelings or Anything.

100

Someone who can stand at my side when Life knocks on the door to say it’s Repossessing our home, and who can Smile when Time pulls down the walls Around us brick by greying Brick. If you’re reading this, please get in touch and it would be great if you could move in as soon as possible because it’s just me at the moment and it’s getting quite lonely in here.

101

Emily Palmer Whilst mulling in the bath A few days after I find out my mum has cancer, I realise why my mind feels strange. It’s like that episode of Sherlock, When that dude gets stabbed with a skewer, But he doesn’t even realise until he takes his belt off. That’s how it feels: Like I’ve been stabbed, but I’m ok. But something isn’t right. And I go about my day, With the skewer stuck in my side, Laughing, having a good time. But something isn’t right.

102

Annie Fan aphelion dyeing my mother’s hair again in june, each strand white and buried thin, as if my hands could find lost pain, stop warm, guttering hail under skin shut in and running out of itself, of the right words to wrap the clouds’ light, hands faint, the pink foxgloves necessary and new under boughs empty; all the birds shot mid-flight. from the window, hawks swerve easier than queer daughters uncovering bright, unguarded things. call them summer; how my mother melts a life out of colour; and the birds still fly about.

103

Marina McCready pokarekare ana my grandma sings me a song in a language i do not speak but on some level i understand. she tells me it is about a land far away where people sail the seas and fall in love as easily as blackcurrants fall off the bush into the palms of a child’s hand. i find it hard to believe that my grandma was a child once, running barefoot through the kauri to the shore, letting tendrils of white water wrap around girlish ankles. her hair was black then, eyes like pounamu but more alive. i look at pictures from somewhere i’ve never been but if it was home to her then that is good enough for me. it’s half the world away but if the earth spins fast enough, i am there, i can hear her laughter, feel salt breeze, sun rays, skipping in the schoolyard, sticky juice of citrus and a tauhou flying the nest. home. i look up the song, speak it aloud in a crude accent, curling the words around my tongue, at once foreign and familiar. now my grandma is gone, but the language isn’t lost yet. 104

Claire Shang errands the corner store is open late, outshines the moon with window price signs. on sale: whole milk. cherries. peanut butter. push the cart fast enough and watch the labels blur. until i hit a bump on the tiling, send cereal boxes careening to the floor. they’re on sale too, two for three. throw em in, we’re always out of cereal anyway. and the milk too. strong bones, strong kids. strong kids who lift grocery bags home. making sure the plastic handles don’t stretch too thin. otherwise how will we use them as garbage bags? keep the bags in the kitchen counter, fold them four times into squares, stack them next to the rubber bands and twist ties. only thing i tie is my shoes. i am jealous of girls who have other things to tie: two dollar bags of white bread shoved to the back of the store. my parents dreamed of freedom and education in a country that cost them their life savings. i dream of biting down on hotel-down-pillow soft, white bread touching my tongue and melting upon contact.

105

Hana Widerman Summers in Sagae, Japan I Here in the countryside old men smoke to suspend themselves in air. My grandmother serves dried persimmons and beer to the men. They compare her to her past self while she nods and laughs. My grandfather drinks all night, telling stories. He wakes up red in the face, walking down the stairs like an afterthought. II The boxes of white peaches at the neighborhood market cost 2500 yen. The pink pockets of their bodies are gifts for the neighbors. We walk with little cotton towels around our necks to catch our sweat.

106

III My grandfather wants to see me in my blue summer kimono, cranes and flowers, mountains and sea. IV It is a hot, humid July. Ajisai curl into each other and fall like snow when it rains. V One year I come late. The summer pears, the cherries, their thin skin, light taste falling rotten from the sky. VI My aunt admires a young man with long hair and strong calves.

107

She opens her blue umbrella and takes off her summer hat. VII A bath for women in the evening might be for men in the morning. My grandmother no longer wears bras, instead white camisoles under her shirts. VIII The stove’s warm breath heats water for tea. I want to ask my mother if she loves my white father. The steam goes through and through and through my head.

108