6 minute read

Katowice: Industrial at Heart

Despite the winds of change blowing through the Silesian region over the last few decades, the core of Silesian identity is not so easily blown over. Katowice and Silesia will always remain industrial at heart. Read on to learn more.

If you’ve ever completed a Mensa IQ test (or even one of those pseudo online tests), you’ll know the format of some of the questions – plane is to...[sky] as boat is to...[water]. So too can the link be made between Industry and Katowice (heck, even the entire Silesian region!).

Advertisement

To understand Katowice and the surrounding area, of course, it’s important to know about historical geopolitical events, but to also know why the area has been seen as such an important addition to any map changing tricks by the regional powers. There’s one simple answer: natural resources. This is a land famous for iron and steel production, but also...coal. Ha haaar, the black gold bringeth more economic benefits than a simple crate of gold, and that’s why the tug of war over the Silesian lands was so persistent. It even led to three Silesian uprisings! Whether it was the importance of the area’s efforts to fund war efforts, the econmic progression of a fledgling state, or efforts to oppose imposed Communist rule, industry has long been a key component of Silesia’s identity. Even now, as the city gradually moves away from traditional heavy industry, it’s fair to say that Katowice and the surrounding area are still industrial at heart.

HISTORY

So how did it all begin? Katowice can count itself as one of Poland’s newer cities, and a direct result of the industrial age. That’s not to say the region was a barren wasteland prior to the age of steam. The history books suggest the area was inhabited by ethnic Silesians centuries earlier, with the first recorded settlement being the village of Krasny Dąb, whose existence was officially chronicled in 1299. In 1598 a village called Villa Nova was also documented to stand in the area now taken up by Katowice. By this time the region had changed from Bohemian hands to the domain of the Habsburg dynasty.

Franz Winkler

Things started hotting up in 1742 when the area changed hands once more, this time as the property of the Prussians. 1788 saw Karolina (the area’s first mine) opened, and by 1822 historic documents note 102 homesteads in the village of Katowice. Two years later the first school was opened and Katowice started making its first steps into adulthood. What really set the ball rolling was the construction of a railway station in 1847. Industrialist and mining mogul Franz Winkler saw this as an opportunity to build up the mines he owned in the region, and Katowice was quickly developed as an industrial town. September 11, 1865, saw Katowice awarded municipal rights and by 1875 it had grown to hold over 11,000 residents, of which half were of Polish ethnicity. The city continued to prosper as an industrial heartland, with coal and steel industries flourishing. By 1897 it was officially designated as a city, though the streets were anything but a happy place; the even split in population between Germans and Poles was already causing friction.

Walcownia Cynku - Zinc Metallurgy Museum

After the defeat of Germany in WWI, and the founding of a newly independent Polish state, native Poles – inspired by the rhetoric of Wojciech Korfanty – staged three uprisings between 1919-21 in a bid to have the Silesia region incorporated into the Second Polish Republic. To prevent outright war from breaking out the League of Nations finally intervened and in 1922 divided the region between both Poles and Germans. Kattowitz, as it was known before this date, fell on the Polish side of the divide and inexplicably became an autonomous voivodeship - a privilege unique from any other province in PL. The inter-war years marked a golden age for the city, with the building of the Silesian Parliament complex and one of Poland’s first skyscrapers (Cloud Scraper) being symbolic of the march into the future.

Silesian Museum today - historical elements mixed with modernity.

Bad news was lurking around the corner though, and in spite of a heroic defence the city fell under German control on September 6, 1939. Aside from the savage destruction of the synagogue and the Silesian Museum, physically speaking the city escaped the fiery fate of many eastern cities, and found itself used as a major centre of manufacturing by the Nazis. Liberation came in the form of Soviet tanks in 1945, and the city was once more Polish – in theory. Between 1953 and 1956 it was renamed ‘Stalinogród,’ and a period of thoughtless development followed; the primitive exploitation of the region’s natural resources saw it marked out as an environmental blackspot with horrific pollution problems. This was a time when walking through the city with a white t-shirt would mean you returned with a grey t-shirt - no, really. Although there was plenty of work in the mines and steel mills, popular unrest with the communist system was growing fast. Living standards had plummeted, with empty shop shelves and round-the-block queues a common sight. In 1980 a series of strikes inspired by the Gdańsk-born Solidarity movement quickly spread around the country. Demands for better living conditions were initially met, but Solidarity continued to lobby for further reforms and free elections. The Kremlin was furious, and with Soviet invasion a looming threat, appointed communist President Jaruzelski declared a state of martial law on December 13, 1981. Tanks roared into the street, subversives were arrested and telephone lines were cut. On December 16 a military assault was launched on striking miners in Katowice’s ‘Wujek’ mine (p.32), resulting in the deaths of nine workers. With Solidarity officially dissolved and its leaders imprisoned, discontent was growing. Pope John Paul II visited Poland, and Katowice, once more in 1983, his mere presence igniting hopes and unifying the people in popular protest. The people would not back down.

Renewed labour strikes and a faltering economy nosediving towards disaster forced Jaruzelski into initiating talks with opposition leaders in 1988, and the following year Solidarity was once more granted legal status. Participating in Poland’s first post-Communist election the party swept to victory, with former electrician Lech Wałęsa leading from the soapbox. Fittingly it was Wałęsa who unveiled a monument in Katowice to the miners killed in 1981 on the tenth anniversary of the event.

PRESENT DAY: INDUSTRIAL TOURISM

Each year, Silesia remembers its industrial heritage during the Industriada Festival.

So what of Katowice, and Silesia as a whole? You’re now in a region which has gone through relatively fast-paced change from heavy industrial beginnings, to one of postindustrial transition. Thanks in part to the collapse of Communism, and the ongoing cooperation between local government and foreign institutions, catastrophe was averted and the ecological balance of the area looks safe. What’s more, it’s now possible to tour the very facilities that made Silesia (and nearly destroyed it!). The gem of the revitalisation is Katowice’s Cultural Zone (p.30), the terrain which was once the Katowice Coal Mine. That’s not to say there are no longer functioning mines across the region – there are still plenty. You have the choice to visit a mix of historical and operational mines, and uniquely, districts such as Nikiszowiec (p.36) which housed workers. Any anoraked enthusiasts are urged to get hold of the excellent ‘Szlak Zabytków Techniki Województwa Śląskiego’ (Silesian Industrial Monuments Trail), a multi-lingual guide with all the must-see sites. Pick it up from any Tourist Information point (p.25).

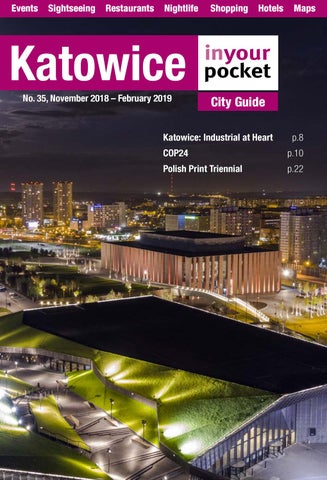

COP24

The UN climate summits, COP (Conference of the Parties) are global conferences on climate policy, and now Katowice will host the 24th meeting between 3-14 December. This is not Poland’s first time holding the event, having previously hosted in Poznań in 2008 and in Warsaw in 2013. In April 2017, UN technical mission delegates, while visiting the capital of Upper Silesia, appreciated the city’s excellent preparation for the event, including its infrastructure.

This year’s summit will include: the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP24), Meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol (CMP 14) and the Conference of Signatories to the Paris Agreement (CMA 1). Around 20,000 people from 190 countries will take part in the event, including politicians, representatives of non-governmental organisations, the scientific community and business sector.

Other than the focal point of COP24 being the Cultural Zone (p.30), there are other places connected to the conference worth visiting. The main market square (Rynek, p.26) will host the Dobry Klimat (Good Atmosphere) ecology tent (p.7) in which you can watch lectures, take part in workshops and meet a host of interesting people! Also check out the family orientated Ekoeksperymentarium on the market square at the intersection of ul. Pocztowa/ul. Młyńska where you can learn about simple steps you can take in your daily life to lessen the your impact on the environment. To find out more, visit COP24.KATOWICE.EU.