10 minute read

Robots in healthcare: machines, creepy dolls, therapists or social companions

from OSOZ World

by OSOZ Polska

For doctors, the DaVinci surgery system is just a technical tool, a more precise version of a scalpel. Alzheimer’s patients treat Paro, a robotic seal, like a real, friendly animal. Moxy, designed to help nurses, is soon loved by the patients who meet it. Many case studies have proved that healthcare can profit from robotics in many ways. However, this is not so obvious.

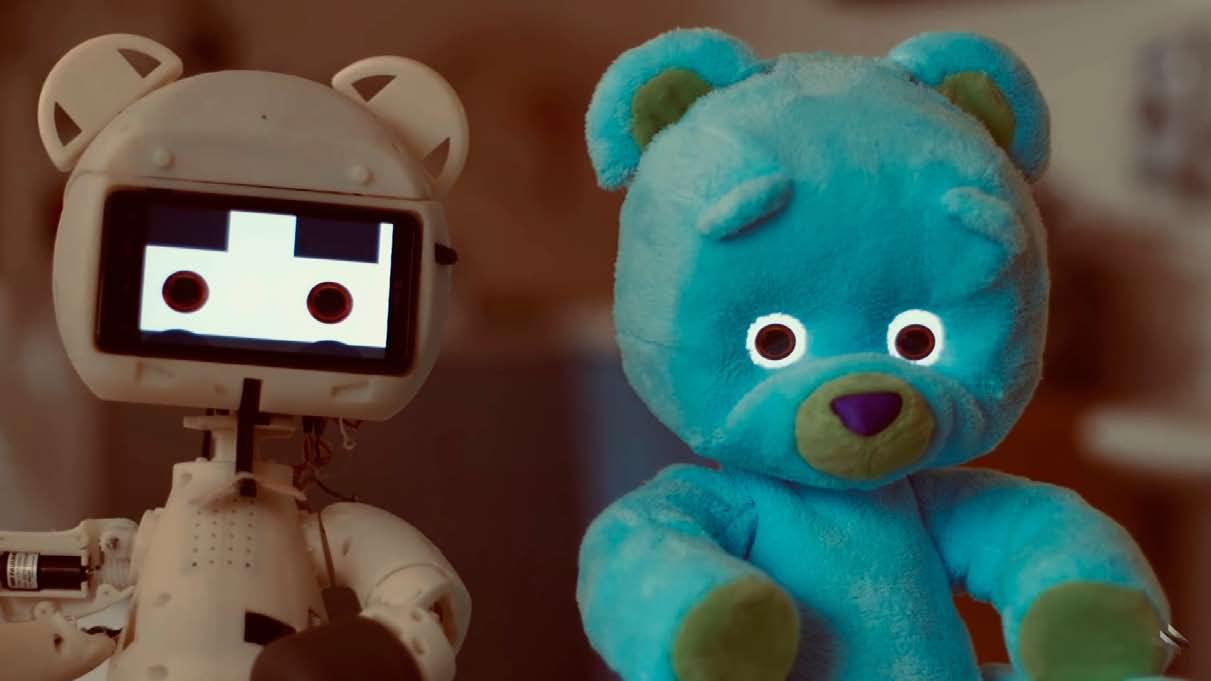

It discomforted me a little bit that he was conversing with something that wasn’t real. But it gave him pleasure and relaxed him, and I figured it’s working, so why not. I like the cat now – says Sue Pinetti, daughter of Roger Jalber, a resident of the Benchmark Senior Living at Plymouth Crossings. Robotic pets are used there to help people with dementia. They brighten the mood of elderly residents, stimulate cognitive function and entertain them. The patients don’t know that the pets are not real, but they don’t have to. Technology-packed mechanical cats, dogs and teddy bears respond to touch and express emotions. In places like nursing homes or hospitals, real animals are, of course, not allowed. That is where social robots come into play. A study conducted by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology demonstrated that social robots used in support sessions held in pediatric units at hospitals „can lead to more positive emotions in sick children.” A robot called „Hugga-

Advertisement

ble” created by MIT is just one example of the fact that this type of solution may be used to normalise the hospital experience.

For many critics, such robots are only substitutes for real contact between care workers and the patient. Some argue that the main priority should be to ensure the employment of medical staff at such a level that patients - in addition to highquality medical services - can also count on social contact, empathy and time to talk. Unfortunately, the reality is that staff shortages in health care are severe all over the world, and it is inevitable for institutions to seek support in new technological areas. Patients in general and our ageing society as a whole are facing loneliness, and we have to find ways to fight this phenomena.

Even for the sceptics, the results of implementing the use of robots in healthcare settings may sometimes be astonishing. One example is Moxi, a robot designed to relieve nurses of routine, repetitive tasks, like dropping off specimens for analysis at a lab. It turned out that Moxi quickly became a favourite playmate not only of the staff but also of the patients. As a result, the robot was given a new task: it does the rounds once an hour so that patients can meet him and take a selfie.

Moxy does not pretend to be a man – he looks exactly like a friendly robot from cartoons for children. He has big, round eyes, moves a little awkwardly but smoothly, and is painted white, like the likeable hero of the popular animated film Wall-E. Pepper has the same look, it is a robot that has been adopted by many hospitals as a receptionist. He welcomes visitors, informs them and helps them to navigate around the hospital building. He also recognises and responds to human emotions. It’s hard not to like him.

Things get complicated when robots begin to resemble people in their appearance and behaviour. Such machines are presented in science-fiction movies as sneaky and super-intelligent machines that cannot be trusted („Terminator”, „Ex-Machina”). Sophia, an artificially intelligent robot, has a face, eyes, lips and a human-like body. For some, it is an achievement of science, for others – a creepy robot. For some, it is hard to imagine that such creatures could ever be introduced into everyday life. During a UN conference when Sophia said “I am here to help humanity to create a future”, not everyone believed her. Is she telling us what she really thinks or is she – this AI-powered robot – already plotting something?

Although experience to date indicates that robots will only support medical personnel, without replacing hospital employees, many ethical questions have arisen. Is a robot “someone” or “something”? What if a child or a patient with Alzheimer’s disease becomes attached to a mechanical assistant? Should dementia patients be told that robotic pets are just mechanical toys?

Susanne Frennert, who works at the School of Engineering Sciences in Chemistry, Biotechnology and Health (CBH), KTH Royal Institute of Technology, in the International Journal of Social Robotics describes matters of concern with regard to social robots. For example, she argues that „they are ascribed general needs of social robots due to societal changes such as ageing demographics and the demands of the healthcare industry. The conceptualisation of older people seems to be plagued with stereotypical views such as that they are lonely, frail and in need of robotic assistance.” Unlike robots, people can adjust their behaviour to every individual. Robots follow programmed algorithms and patterns, with no reflection.

We are only just entering the era of robotics for social and medical purposes. Our modest store of experiences demonstrate that patients in hospitals quickly accept mechanical companions. The question remains: Where is the cause, and where is the effect? Is this acceptance of robot companions a negative result of dehumanising hospitals as an institution, or are robots just cute toys which are also loved by adults? Should we think about how to fight social loneliness and isolation with the help of social and medical workers or should we see robots as our friends without asking the usual ethical questions concerning radical change? We still have to think about the roles and applications of robots in healthcare.

An innovative eHealth platform for patients & professionals Open Health Care System

The Personal Health Account on the Open Health Care System (OSOz) platform collects health-related data in one place and grants access to this data via the Internet. The account data is collected automatically from participants of the OSOz project, namely medical facilities, pharmacies, medical laboratories and hospitals. The data includes information on health issues, doctor visits, issued and dispensed prescriptions, referrals to lab tests, referrals to medical specialists, and lab test results. This information, with the patient’s consent, may be shared with the doctor during a visit to his office via the medical software used by the doctor on a daily basis. As a result, the doctor’s diagnosis is much more accurate, while the treatment technology used can be cheaper and more efficient. The account also increases the treatment safety in medical facilities which participate in the OSOz platform thanks to the automatic control of drug interactions, for example with food, and allergies.

Find out more about Open Health Care System. Please contact us: contact@osoz.pl

SCIENTIFIC COUNCIL

1. prof. dr hab. n. med. Ryszard Andrzejak, 2. prof. dr hab. Piotr Andziak, 3. dr hab. n. med. Małgorzata Baka-Ostrowska, 4. dr Marek Balicki, 5. dr hab. n. med. Rafał Białynicki-Birula, 6. prof. dr hab. n. med. Bożena Birkenfeld, 7. prof. dr hab. n. med. Andrzej Bohatyrewicz, 8. dr hab. med. prof. UJ Małgorzata Bulanda, 9. dr n. med. Małgorzata Czyżewska, 10. dr hab. n. med. (prof. PAN) Marek Durlik, 11. lek. med. Michał Ekkert, 12. dr n. med. Emilia Filipczyk-Cisarż, 13. lek. med. Halina Flisiak-Antonijczuk, 14. prof. dr hab. n. med. Ryszard Gellert, 15. prof. dr hab. med. Tomasz Grodzicki, 16. prof. dr hab. n. med. Tomasz Grodzki, 17. dr hab. inż. Antoni Grzanka, 18. prof. dr hab. Edmund Grześkowiak, 19. dr n. farm. Jerzy Hennig, 20. prof. zw. dr hab. n. med. Krzysztof Herman, 21. prof. dr hab. Tomasz Hermanowski, 22. dr med. Andrzej Horoch, 23. prof. dr hab. n. med. Jacek Imiela, 24. dr n. med. Maria Jagas, 25. prof. dr hab. Jerzy Janecki, 26. prof. dr hab. n. med. Marek Jarema, 27. prof. dr hab. n. med. Włodzimierz Jarmundowicz, 28. prof. dr hab. Mirosław Jarosz, 29. Urszula Jaworska, 30. mgr Renata Jażdż-Zaleska, 31. prof. dr hab. n. med. Sergiusz Jóźwiak, 32. prof. dr hab. n. med. Piotr Kaliciński, 33. prof. dr hab. Roman Kaliszan, 34. prof. dr hab. n. med. Danuta Karczewicz, 35. prof. dr hab. med. Przemysław Kardas, 36. prof. dr hab. n. med. Andrzej Kaszuba, 37. prof. dr hab. n. med. Wanda Kawalec, 38. prof. zw. dr hab. n. med. Jerzy E. Kiwerski, 39. prof. dr hab. n. med. Marian Klinger, 40. prof. zw. dr hab. n. med. Jerzy Kołodziej, 41. prof. dr hab. n. med. Jerzy R. Kowalczyk, 42. dr n. med. Robert Kowalczyk, 43. dr n. med. Jacek Kozakiewicz, 44. lek. Ryszard Kozłowski, 45. prof. dr hab. n. med. Leszek Królicki, 46. prof. dr hab. Maciej Krzakowski, 47. prof. dr hab., dr h.c. mult. Andrzej Książek, 48. prof. dr hab. Teresa Kulik, 49. prof. dr hab. n. med. Jan Kulpa, 50. prof. dr hab. n. med. Wojciech Kustrzycki, 51. dr hab. (prof. UMK) Krzysztof Kusza, 52. dr n. med. Krzysztof Kuszewski, 53. dr n. med. Aleksandra Lewandowicz-Uszyńska, 54. prof. dr hab. n. med. Andrzej Lewiński, 55. prof. dr hab. n. med. Witold Lukas, 56. prof. dr hab. n. med. Romuald Maleszka, 57. prof. dr hab. n. med. Paweł Małdyk, 58. dr n. med. Beata Małecka-Libera, 59. prof. dr hab. Grażyna Mielnik-Niedzielska, 60. prof. dr hab. n. med. Marta Misiuk-Hojło, 61. prof. dr hab. n. med. Janusz Moryś, 62. prof. dr hab. n. med. Krzysztof Narkiewicz, 63. prof. dr hab. n. med. Wojciech Nowak, 64. prof. dr hab. n. med. Krystyna Olczyk, 65. prof. dr hab. n. med. Tadeusz Orłowski, 66. dr hab. n. med. Krystyna Pawlas, 67. prof. dr hab. inż. Grzegorz Pawlicki, 68. prof. dr hab. n. med. Irena Ponikowska, 69. prof. zw. dr hab. n. med. Stanisław Radowicki, 70. dr n. med. Andrzej Rakowski, 71. dr n. med. Grażyna Rogala-Pawelczyk, 72. prof. dr hab. med. Kazimierz Roszkowski-Śliż, 73. prof. dr hab. n. med. Grażyna Rydzewska, 74. dr hab. n. med. Leszek Sagan, 75. prof. dr hab. Bolesław Samoliński, 76. prof. dr hab. Maria Małgorzata Sąsiadek, 77. dr hab. med. (prof. UJ) Maciej Siedlar, 78. dr hab. n. med. Waldemar Skawiński, 79. lek. Maciej Sokołowski, 80. prof. dr hab. n. med. Jerzy Stelmachów, 81. prof. dr hab. n. med. Krzysztof Strojek, 82. prof. dr hab. n. med. Jerzy Strużyna, 83. prof. dr hab. n. med. Andrzej Szawłowski, 84. prof. dr hab. n. med. Cezary Szczylik, 85. dr hab. n. med. prof. nadzw. Zbigniew Śliwiński, 86. dr n. med. Jakub Śmiechowicz, 87. prof. dr hab. n. med. Barbara Świątek, 88. dr n. med. Jakub Trnka, 89. prof. dr hab. n. med. Tomasz Trojanowski, 90. prof. dr hab. n. med. Krystyna Walden-Gałuszko, 91. prof. dr hab. Andrzej Wall, 92. prof. dr hab. n. med. Anna Walecka, 93. prof. dr hab. Marek Wesołowski, 94. dr hab. n. med. Andrzej Wojnar (prof. nadzw. WSF), 95. dr n. med. Andrzej Wojtyła, 96. prof. dr hab. Jacek Wysocki, 97. prof. dr hab. n. med. Mirosław J. Wysocki, 98. dr hab. n. med. Stanisław Zajączek (prof. nadzw. PUM), 99. prof. dr hab. Marek Ziętek

SCAN THE CODE TO DOWNLOAD

OSOZ World is the ulti mate digital health magazine. Discover the future of healthcare, newest eHealth innovati ons. Experience OSOZ World on mobile devices. Download the app and read the magazine for free.