DAVID MACH HEAVY METAL

‘Heavy Metal’ is one of your most ambitious and wide-ranging exhibitions to date and has been a number of years in the making. Tell us about the title for the exhibition and what links these varied works.

Heavy Metal covers a lot of territory. The title goes all the way back to my childhood, my teenage years, entering art college at eighteen and on, right up to the kinds of sculpture and building I want to design and make now.

I shiver now when I think of myself and other wee boys and girls, playing on the railway tracks by the sea, dodging in and out between the diesel engines dragging wagons backwards and forwards to the docks full of coal and wood and other goods. We’d climb over a wall onto the metal bridge held together by giant rivets and antagonise the train drivers - them shouting at us, us goading them. Mad. Some of us died doing that. There was always some kid dying on that bridge. On it, or under it, dragged down to get caught in the river below.

Leaving school I’d work in the yards where they constructed giant contraptions to get the oil out of the North Sea. Platforms constructed entirely out of steel, so big the top of them could disappear into dirty weather’s low cloud. I also worked in a whisky bond, in warehouses so big they made the end scene of Raiders of the Lost Ark look small. I thought all of the whisky in Scotland would surely end up in there. My job? Seven days a week, twelve hours a day I helped weld and bolt together the vast network of steel cages lined with rails, that would hold millions of whisky casks.

Metal, steel was everywhere, and in vast quantities, shaped, designed, welded and bolted into everything you could possibly imagine. Those were days when your dad was able to raise the entire family with only his one wage coming into the house, when your mother stayed at home to bring you up, when it seemed that everybody in the neighbourhood was fully employed and when hardly anybody wore safety gear. Absolutely everything was politically incorrect and if you took too long to gaup at some amazing structure somebody would come up behind you and slap you on the head or worse, kick your arse, bawling an instruction ‘‘Don’t just stand there. Do somthin!” It was a brilliant time and clearly infected me with a desire to make amazing, daring things happen.

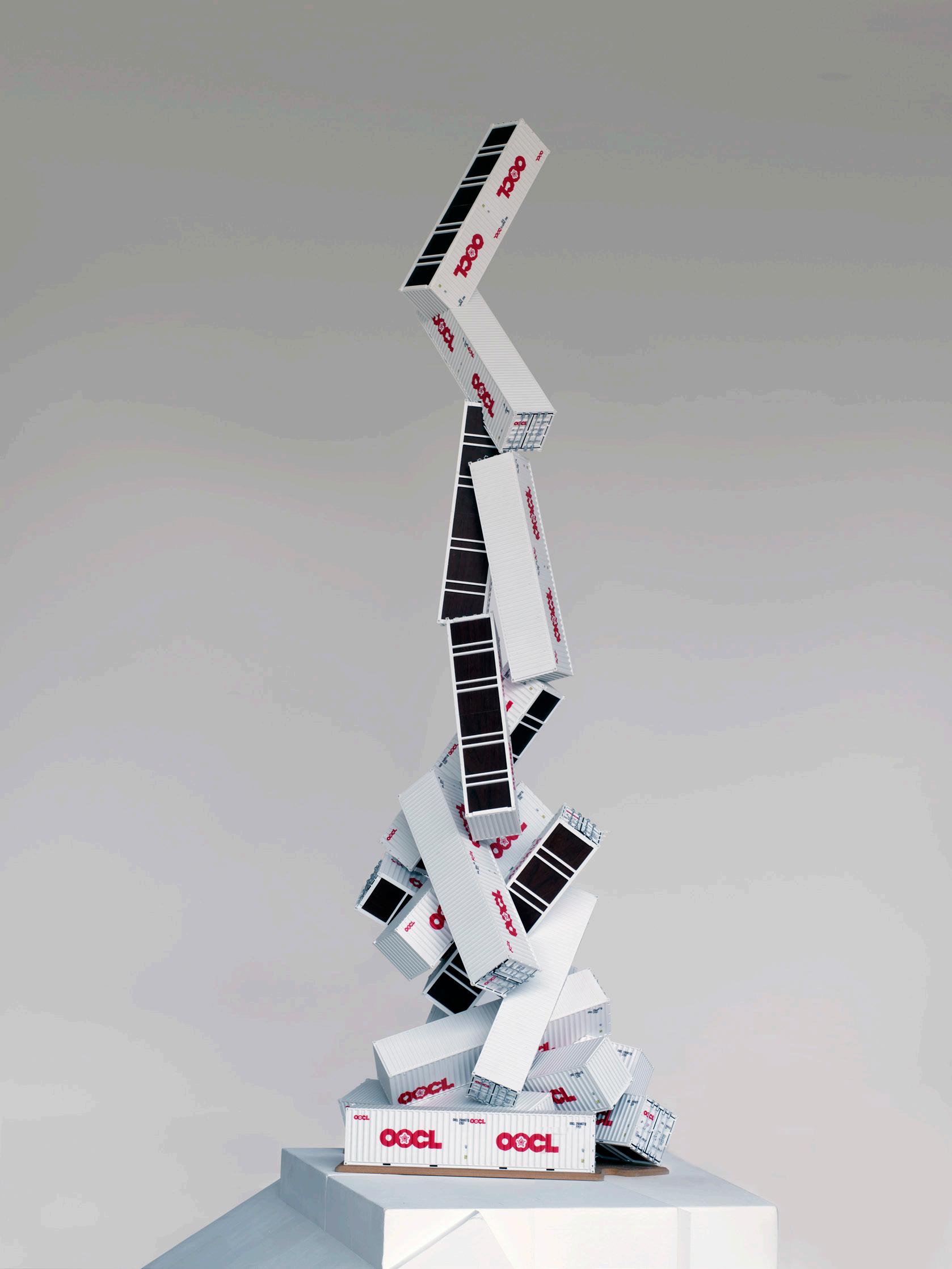

If you visit the show or just flick through the catalogue you’ll notice a lot of ‘Heavy Metal’. There are some fifteen to twenty maquettes of sculpture and architecture in the show kicking off with sculptures I worked on in the late 1980’s and continuing on to projects I am working on now. You’ll see a lot of ideas using sea containers, cars, vans all requiring unfeasible engineering to make different parts of different things fit together, fuse together even, into one unlikely construction, a sculpture, that you can walk around and lately buildings that you can enter.

Heavy Metal is also a reference to music. Not just to music that I like, I do like many different kinds of music, but to rhythm, to the beat of that, maybe even to the beat of industry and how I felt that beat was

infecting my work. It might also be a reference to ideas I had about the difference between making music and making three-dimensional art. How could I make sculpture as exciting, as driven, as inspiring, as honest and as ’live‘ as music. So indeed Heavy Metal covers a multitude of sins.

The exhibition explores past commissions as well as current and future projects. Edinburgh Park is a significant current project and will be the first time your monumental work has delved into the realm of architecture. What inspired your idea for Mach1 and how has the project developed along the way?

Mach1 grew quite organically, starting off as response to a brief for a marketing suite for a 500 acre site of new buildings, homes and offices at Edinburgh Park near Edinburgh Airport. The brief already invited containers to be used, all of the previous designs not quite what the commissioners wanted.

For me, because I had used sea containers for some time it was a chance to do something different and to use the containers as huge building blocks, not like everybody else horizontally and vertically, but to have them come together naturally, like basalt blocks or crystals. Thinking of them like that the containers could grow out of each other at crazy angles, almost geologically. Using them like that allowed them to escape from the horizontal and the vertical, to create something way more dynamic, something way more Fingal’s Cave or Giant’s Causeway.

I had a lot of fun working on a very crude model starting simply with Bacofoil boxes cut to scale, working out not just a structure but a structure that could hold an interior. That’s an interesting thing for a sculptor to do, we’re not normally overly concerned with the interior of things. In this case though it was necessary to consider that. You can’t have a marketing suite if you can’t get into it and it was exciting for me to jump from sculpture to architecture.

That basic design with those boxes was then able to be developed by the architects and engineers involved in the project into a real building which is now waiting to go up. Brexit, Covid, recession and rising material costs have all delayed Mach1 from appearing on site but with a bit of luck it will come to fruition next year, no longer a marketing suite but now an art gallery. With a bit more luck it’ll become a venue for the festival or the Fringe in Edinburgh. My preferred choice? A comedy club. God knows we could do with the laughs.

Another substantial project you are working on is for a site in Mauritius which you visited for research just before the show. I imagine your final design is still under wraps at this stage but can you give us an idea of what the concept might be and tell us how important you think research is when working on a project like this? How does your making process change?

We’re at the very early days of this project but in December I flew out and spent five days on the island to see as much as I could and absorb as much of the local vibe as possible. It’s a really interesting place. Feels very new. It’s multicultural. I love that. Everybody’s an immigrant one way or another, people have had to travel here to get here for the island’s entire history. I love that too. There’s hardly anything indigenous, not the people, not the flora and fauna. Practically everything that makes this island tick has been and has to be imported and yet, the island, to me, doesn’t feel spoiled. There’ll be plenty of history to show

it being interfered with in lots of different ways but it feels like it’s survived that. It’s like a teenager finding things out, ready for more. That might be a naïve take on the place after just a few days but I have to say I felt good there and of course it inspired me immediately in a dozen different ways.

My job now is not to be overrun by all that information, all of those sites (the landscape can be spectacular) all of my romantic schmaltzy notions about the place mixed in with hard facts. As a sculptor I need to come up with something, a public work that is relevant to the island and the people who live there and how they relate to the rest of the world. I also want whatever I make to be challenging. I want it to provoke thought and encourage a response. It’s a curious mix, and of course I can’t separate my mind, my heart, my stomach, who I am from, how I think, from any of this.

So begins the adventure of narrowing down an idea, shaping it into interesting forms made with something that belongs to this land and its people. I know that no matter how hard I try to tailor-make it, it will delight, infuriate, surprise and mystify anyone looking at it so there’s no point in playing to the crowd.

You’ll guess that I’ll be using containers on this job. They are integral to Mauritius’ existence for trade and basic survival so they will definitely feature and I know, now having being injected with the architecture bug, that whatever I come up with won’t just be a sculpture. It will have a useable interior and something I hope that will draw the islands diverse population to it.

You’ve spoken a lot in press interviews about your unorthodox approach to materials in your sculpture and their importance of being recognisable but used at scale. A number of works in this exhibition use shipping containers which have been a continuous component of your work over the past three decades. Can you expand on why you find them so appealing?

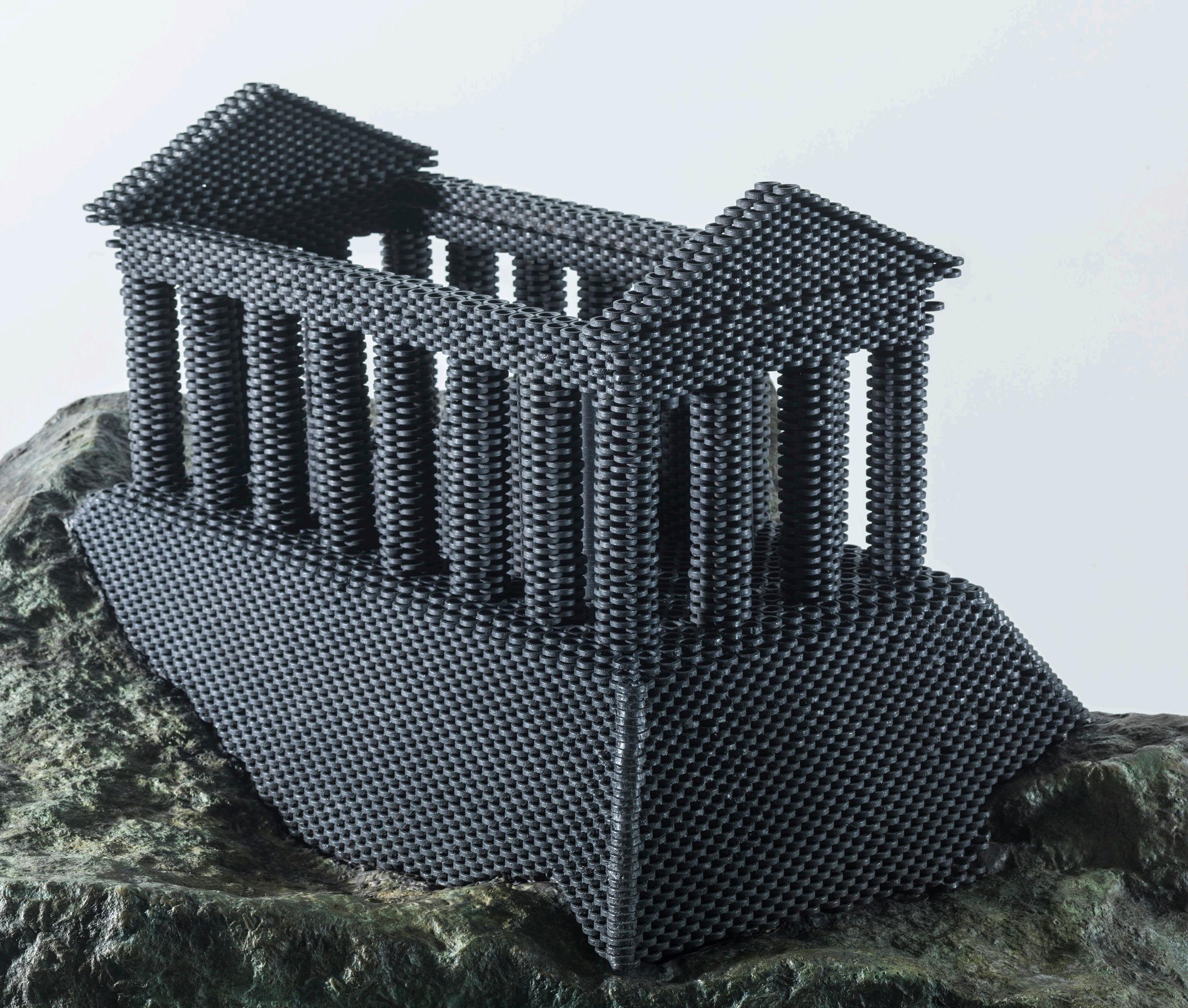

Well, if you know me, you’ll know I can bang on about sea containers for ever. How they’re like minimal Greek temples with their long ribbed sides, like columns, leading to a gable end. How everything we buy in the world is shaped, sized to fit into one of these things. How they’ve been dropped from planes to fall into Amazonian jungles to be worshipped by tribes still primitive there. How they fall off the gigantic ships carrying them around the world to become the most dangerous contemporary iceberg to yachtsmen and women, almost all of their bulk hidden beneath the waves, barely showing above the waterline. How they’re used in war zones to become accommodation for the poor, the destitute, the scared-to-hell citizens making up almost an entire city of poor souls - I can go on and on. I can’t get enough of them.

For me containers help feed into my need to connect with the world. They allow me to be grand, to be large, to be extravagant and they invite and offer up unfeasible, unlikely, undo-able even ridiculous ways of building and designing with them. They enable me to stretch ideas and engage in challenging engineering techniques, methods of construction and even meanings of ideas. Not bad for a bit of heavy metal.

This might all sound ridiculous but for me, the whole effort of making art can’t be ridiculous enough and that attitude may have something to do with the materials, the objects I prefer using to make my art. It’s what brings me to sea containers, to telephone boxes, to matches, coathangers, magazines etc, etc, etc it’s certainly an ingredient.

Truthfully, I will have worked out other things with those objects that I find important. What they mean not just to me, but to other people, their meaning. In other words, how they play their part in the world and how they connect all of us together and root us to our world.

Two maquettes for past commissions, your much loved Brick Train in Darlington and the monumental temporary project Temple at Tyre which was installed in Leith in 1994, have been specially cast in bronze for exhibition by Pangolin Editions. Returning to these works I wonder if it has made you feel nostalgic at all for the projects in your early career that allowed you to be so daring - do you think the artistic landscape and opportunity for this kind of project for artists has reduced? Have we become more conservative in our commissioning?

The train was a really exciting project, not least because it wasn’t just a sculpture but the size of a building too. I learnt a lot working on that project with so many different teams of architects, surveyors, engineers, the bricklayers themselves, even mortar and bat specialists (some special ‘bat bricks’ are built into the work). There was a considerable amount of detail to go into, not just in the sculpture’s building but in the politics involved, local and nationwide, and in the effort required to keep the project rolling along.

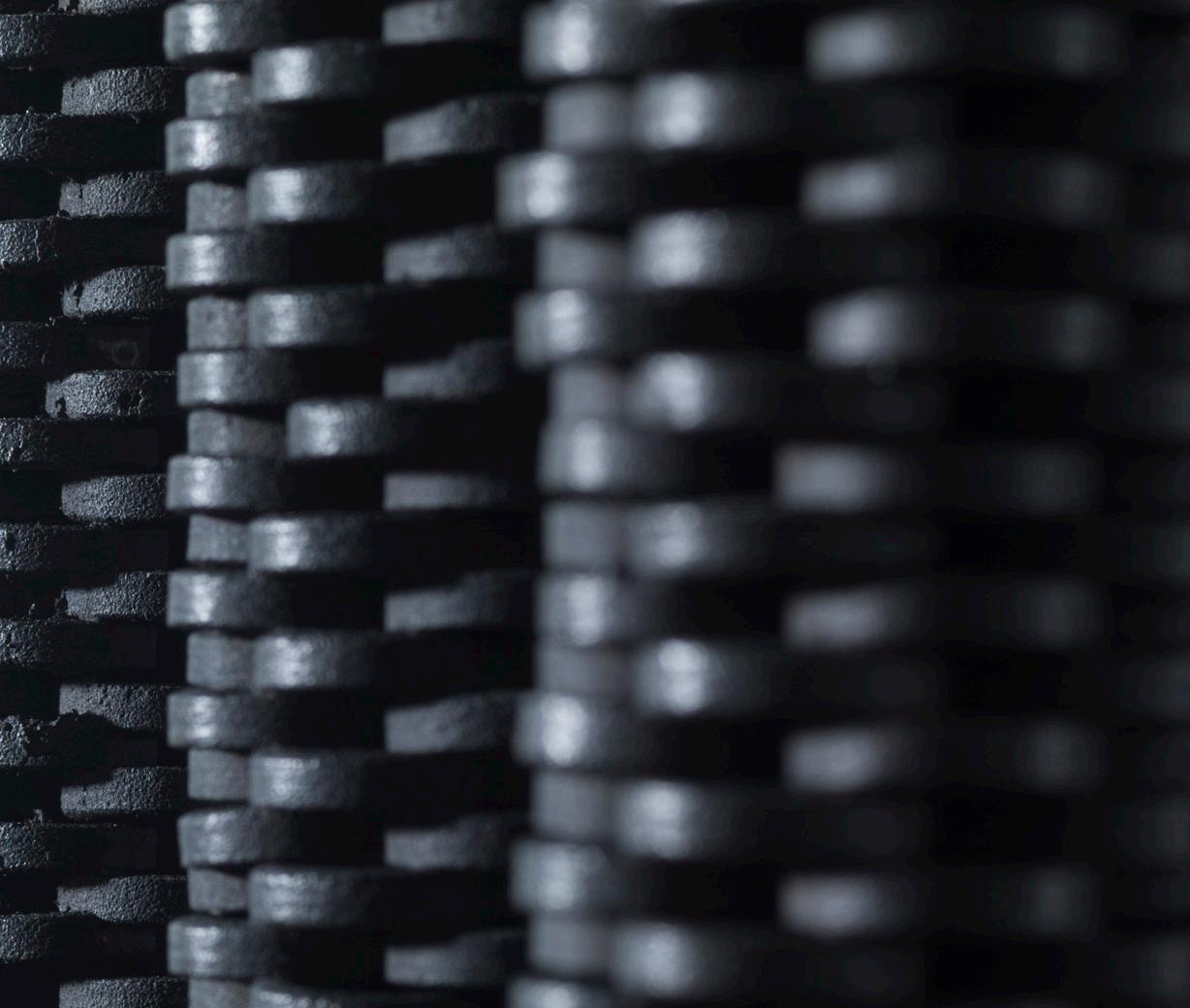

Temple at Tyre was a huge project we built on Victoria Dock in Leith and I think still holds the record for being the largest temporary piece of public art ever built in the UK. It was commissioned by the Edinburgh District council in 1994 and was only on view for a month. It was impossible to ignore as it was visible from a number of view points throughout Edinburgh and was built from 145 sea containers and over 8,000 tyres.

I learned with both projects (although I should have been plenty aware of it before) just how much an artist needs to realise that he or she is providing the drive to make everything happen. It’s a valuable lesson to learn. Never take your eye off the ball, or you’ll end up making something different to your original design, something you don’t like - or worse end up making nothing at all.

I’m not really nostalgic about much to be honest or maybe that’s the wrong thing to say. I’ll remember enjoying the physical work and the challenges involved in both of those projects. I’ll remember a lot about the people I worked with, the people on the team. In Temple at Tyre’s case, a bunch of rogue Geordies from the Byker estate in Newcastle. I still have good friends from creating Train but nostalgia suggests ‘a longing to go back to.’ I don’t feel that. I have a longing to go forwards into the next set of challenges, the next kind of work, to meet the next set of people helping me to create something. I carry all the things that happened to me before into that next venture.

I think the world in general has definitely become more conservative. The art world has too but that’s not to say that opportunities to be daring are getting fewer and farther between. They are still there and I see plenty of good art out there, plenty of good ideas being realised. I know people who design and make fantastic things. I know too we would all probably agree that the fight to make them is harder but they still happen and anyway, maybe that’s the way it should be. If it was easy everybody would be doing it. Maybe that tells you something about me though, maybe I prefer the fight.

Given you’re no stranger to working on a monumental scale I wonder if there are any other artists or architects who inspire you that work in a similar way?

I’ll try to step back from the monumental for a minute. Not everything I like has to be that big, though I do see sculptors work, architects designs too that I admire. I’m also inspired by film, by good editing, by good scripts. Music is a colossal inspiration. I’ll listen to any number of things wishing daily I had composed them, wishing I had written the lyrics. I listen to a lot of comedy. Comedy writing is something that has

power. I’m inspired by all of these things and in fact probably suffer from over-inspiration. I don’t know if that’s something I should worry about, something that I should try to limit - I don’t think I’m being held back by it so far.

It probably has something to do with wanting to be an ideas monger. Someone who has a continual stock of ideas developing fast. I remember hearing Elvis Castello talking about how tunes would appear in his head. He said it could be ten tunes in a day all worth remembering. This is the age before mobile phones, so in order not to forget, not to lose these tunes in his head he would go to a telephone box and hum a few bars into his answer machine. I loved that idea and I suppose I’m a bit like that or I certainly want to be.

Many of your recent exhibitions have involved large installations made of tonnes of newspapers carrying heavy objects such as cars and containers. These involve a team of assistants helping you bring an element of performance or dance to create the final work. Although there are a number of individual pieces in ‘Heavy Metal’ rather than a striking singular piece you’ve created a complex central construction that stretches diagonally across the gallery almost like an installation of ideas. Would that be an accurate description and what do you think drives your approach?

After all these years I still don’t like the isolation of the studio. I prefer to build installations and to work as publicly as possible as a kind of sculptural performance artist. I’ve built works in shopping centres, parks, streets, moving trains, swimming pools and car showrooms as often as I have in galleries or museums. I enjoy the challenges of trying to manipulate unorthodox materials, preferably in vast quantities, in the face of an ever-mounting but still beatable bureaucracy and in front of as large an audience that I can get.

Heavy Metal is a different kind of presentation to this. It may not even be an exhibition. It feels more like a trade show. It’s a kind of “Hello, my name’s David Mach, I make art of all sizes and shapes and subjects and materials, here’s some of the things I’ve done, some of the things I’m doing and some of the things I’m going to do.” If that’s right then you’d expect to see those things on single plinths dotted around the gallery. I’ve seen plenty of shows like that. I don’t like them and I know it’s not the way I want to do things so Heavy Metal becomes pretty much what you describe in your question. Not a room full of separate plinths, there are one or two - but a room dominated by a long central construction, an installation in itself. The bronze maquette of the Brick Train is the first piece you see and a four-metre-long lead into that installation. It introduces you to nearly fourteen metres of connected platforms, boxes and plinths, all joined in a long line with models that various artists and friends have helped me realise.

Sitting on top of that, you are invited to come across the wide variety of ideas for sculpture and architecture that are currently roaming around inside my head. It’s like a conveyor belt of ideas, more like a trade fair than an exhibition of art, and as I say this, I realise the next show is going to have the movement of a conveyor belt added to it.

Both light and dark humour can be seen in your work. If You Go Down to the Woods Today, The Infiltrator and The Oligarch’s Nightmare both touch on the darker side and are in direct contrast with the much lighter humour of Love Shack, Love, Joy, Peace & Happiness and your homage to the white van driver Hommage au Chauffeur de la Camionnette Blanche. How important is humour to your work?

I realise I’ve said on these pages that I see plenty of good art out there, plenty of good ideas realised but I have to say that there’s also a lot out there that ain’t so good. Artists are a serious bunch. Art’s a very serious business. I’ll steal Bill Shankley’s quote about football and say it about art…“it’s not just a matter of life and death, it’s far more serious than that.” You have to be careful with that seriousness. There’s a kind of curse attached to it that can wipe that seriousness out. It can kill ideas, make them disappear. It can certainly kill any humour lingering around your art and I suppose I worry about that because my instinct is to be funny. I worry about trying to make something funny. It needs to be funny by accident or you’d be better just leaving it well alone. The pith, the irony, the drole, the satirical, even the sarcastic, it all needs to be there already. Remember the curse. You’re an artist, not a comedian. You can tell good stories and you can make people laugh and it’s for sure a great thing to be able to do and a sound well worth hearing but remember, there’s a reason when you walk out of the Tate or the Hayward galleries that you don’t hear giggling coming from the inside.

You grew up in Fife, Scotland and have recently returned to live there. If you were asked to create a new monumental public work to celebrate your homeland what would it be and where?

The Kingdom of Fife! I’ve thought of a whole trail of things I’d like to build in it, make it the Kingdom of Culture, the Kingdom of Sculpture. It’s just gagging to have a monster sculpture sitting near the bridges across the Forth. I suggest a stag standing on a revolving platform just above the water level, the body of the great beast built as high as the rail or road bridges. It would be a welcome to Fife, an intro to the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. It starts here with a stag, superbly antlered, a la Landseer turning in the wind as the platform turns to face north, south, east and west. Made of bronze of course it would be Scotland’s Statue of Liberty and a great entry into Fife itself, where, let’s face it we should have a considerable work of art every forty or fifty miles or so making a trail to be followed through the entire Kingdom turning Fife into the biggest, most interesting sculpture park in the world.

You’ve said in previous interviews that you hope your work provokes a reaction. What reactions do you hope to illicit from viewers to this exhibition?

You have to wait for reactions, you can provoke them but you don’t know what they’re going to be. I would prefer of course pats on the back, applause, cries of genius, tears of gratitude and filthy lucre slapped into my sweaty little mitt. I know I want to stimulate, to make an audience think. I want the hairs on the back of their neck to stand on end, their hearts to pump and their stomachs to churn but what they’re gonna do is what they’re gonna do. You’ve gotta leave it up to them. I hope if there is a message within the work, it is to stand up and be counted. Put yourself out.

Stack: Chiswick Roundabout Maquette 2022, Model Unique 220 x 64 x 58 cm

If You Go Down to The Woods Today 2022, Mixed media with bronze bear Edition of 3 146.5 x 174 x 113 cm

Brick Train

1997, bricks

Unique

29 metres long

Darlington, County Durham

(left & previous)

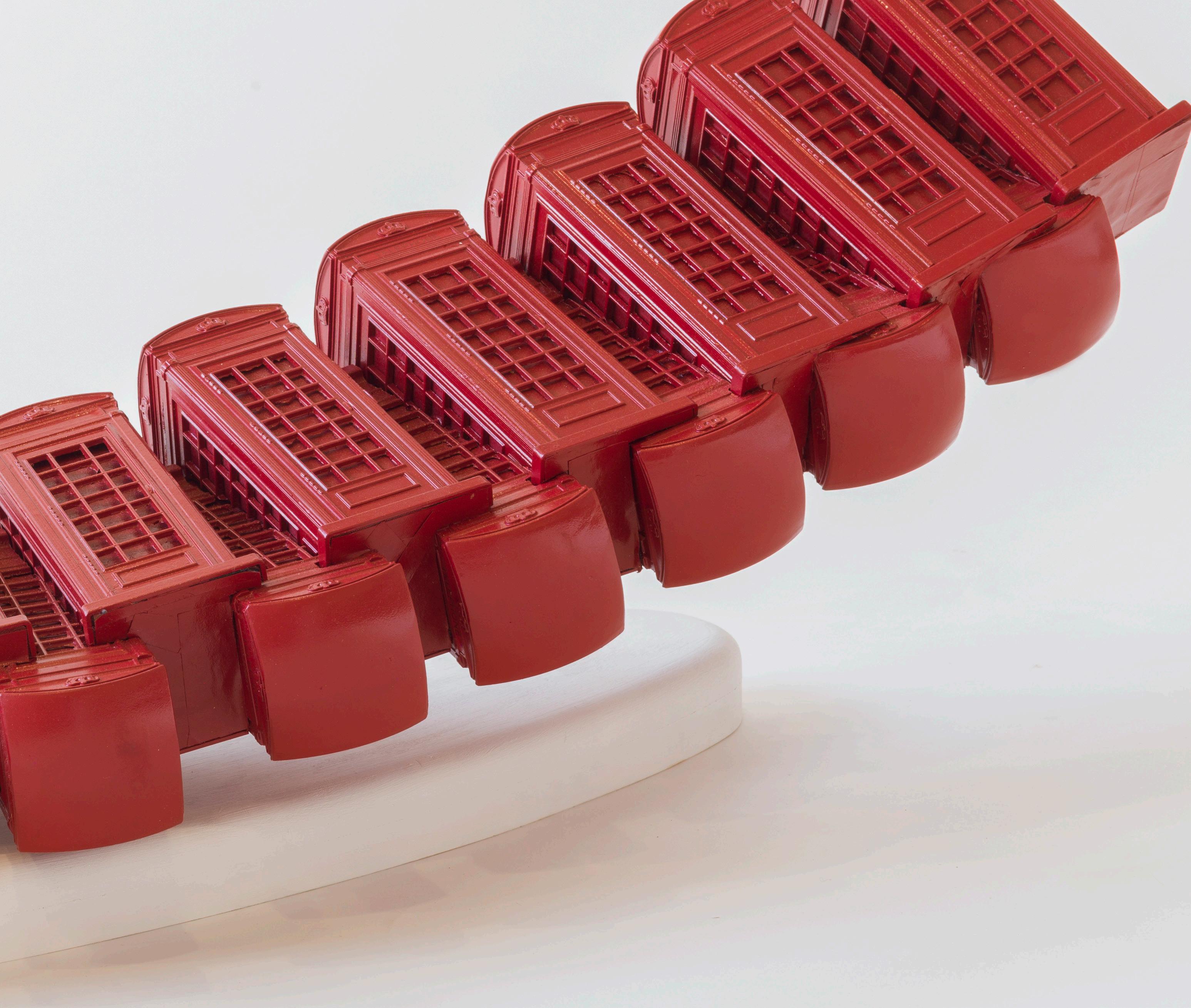

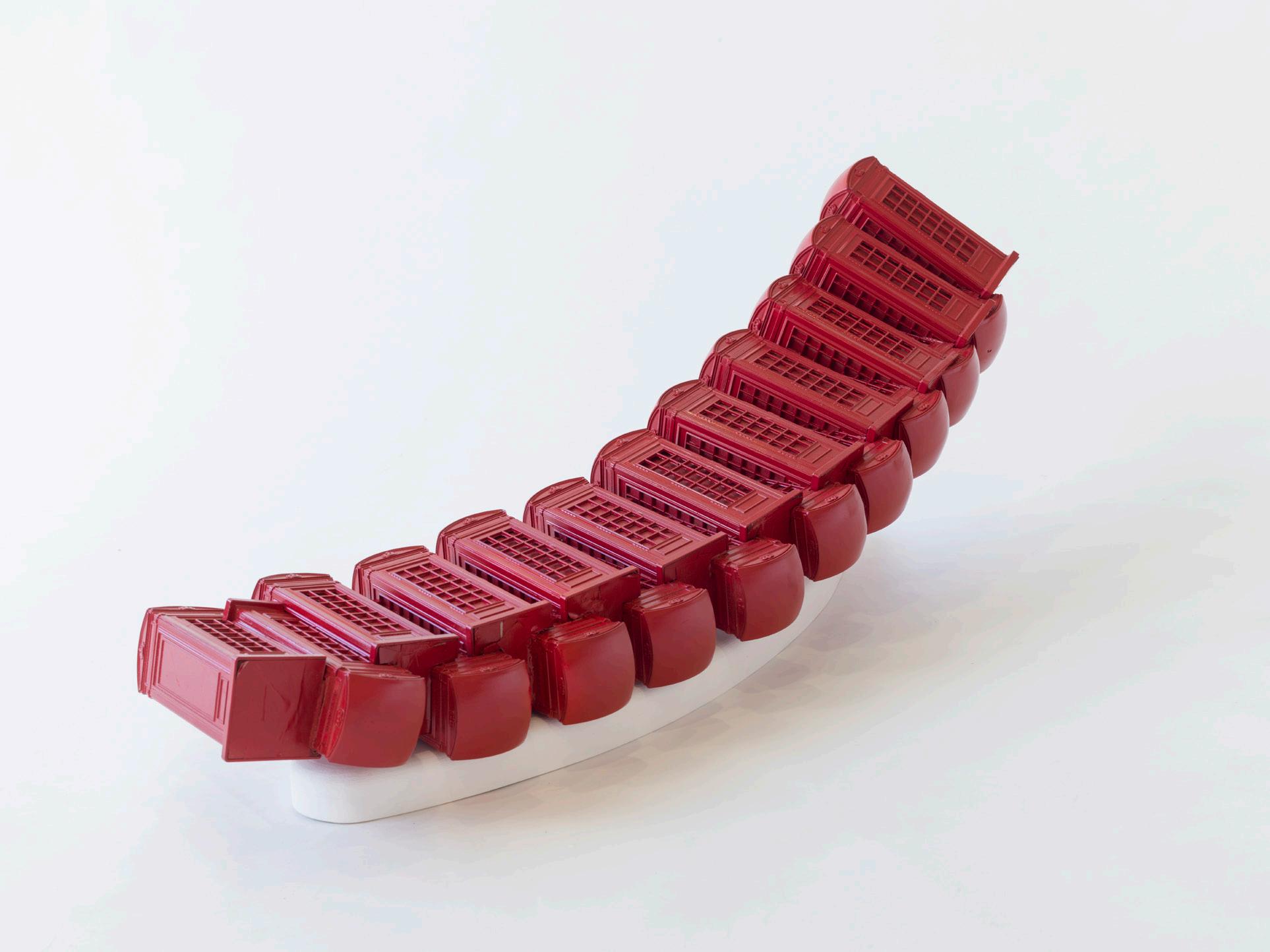

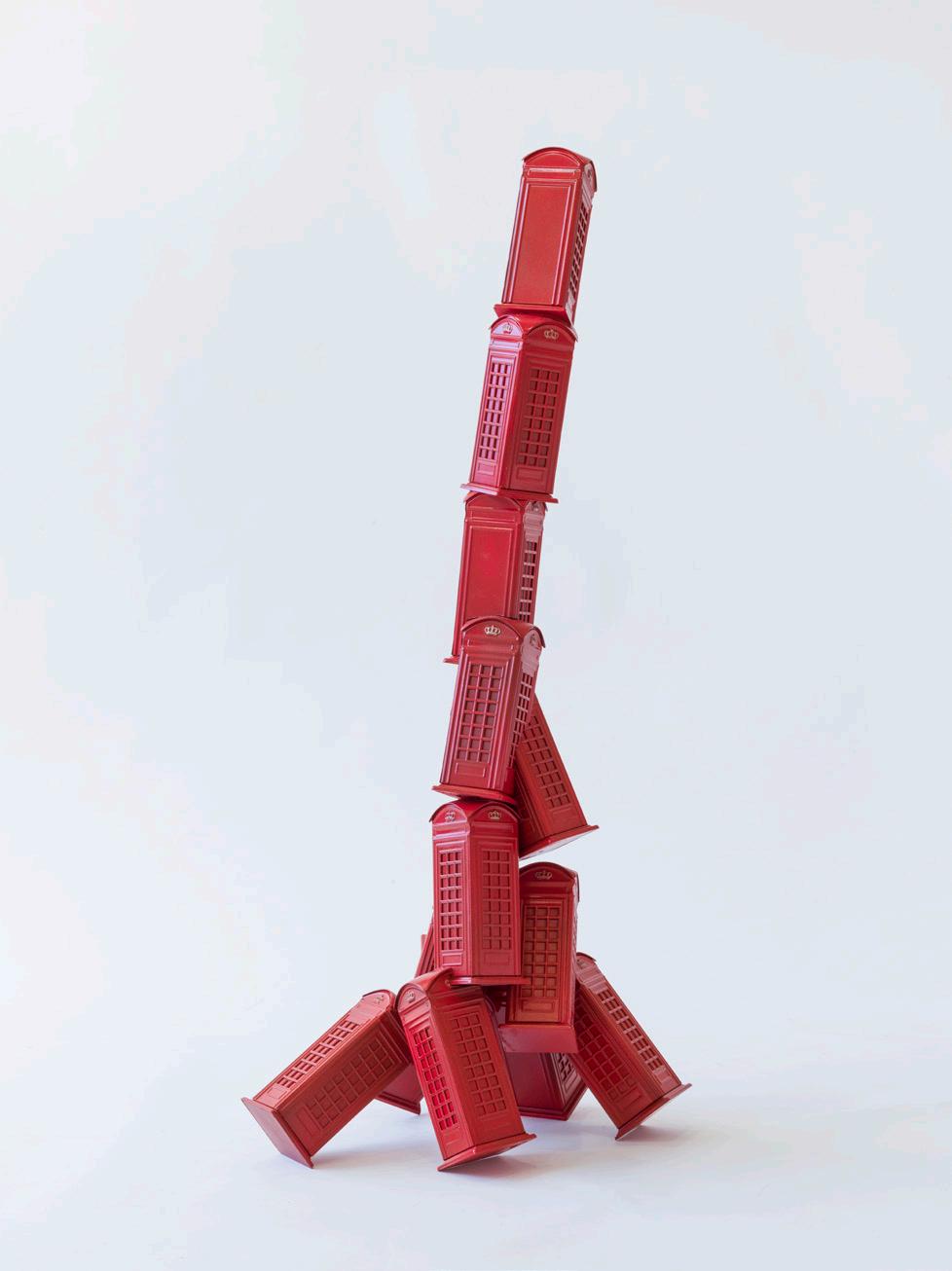

Telephone Box Maquette II

2023, Model for bronze

Edition of 5 40 x 95 x 23 cm

(right)

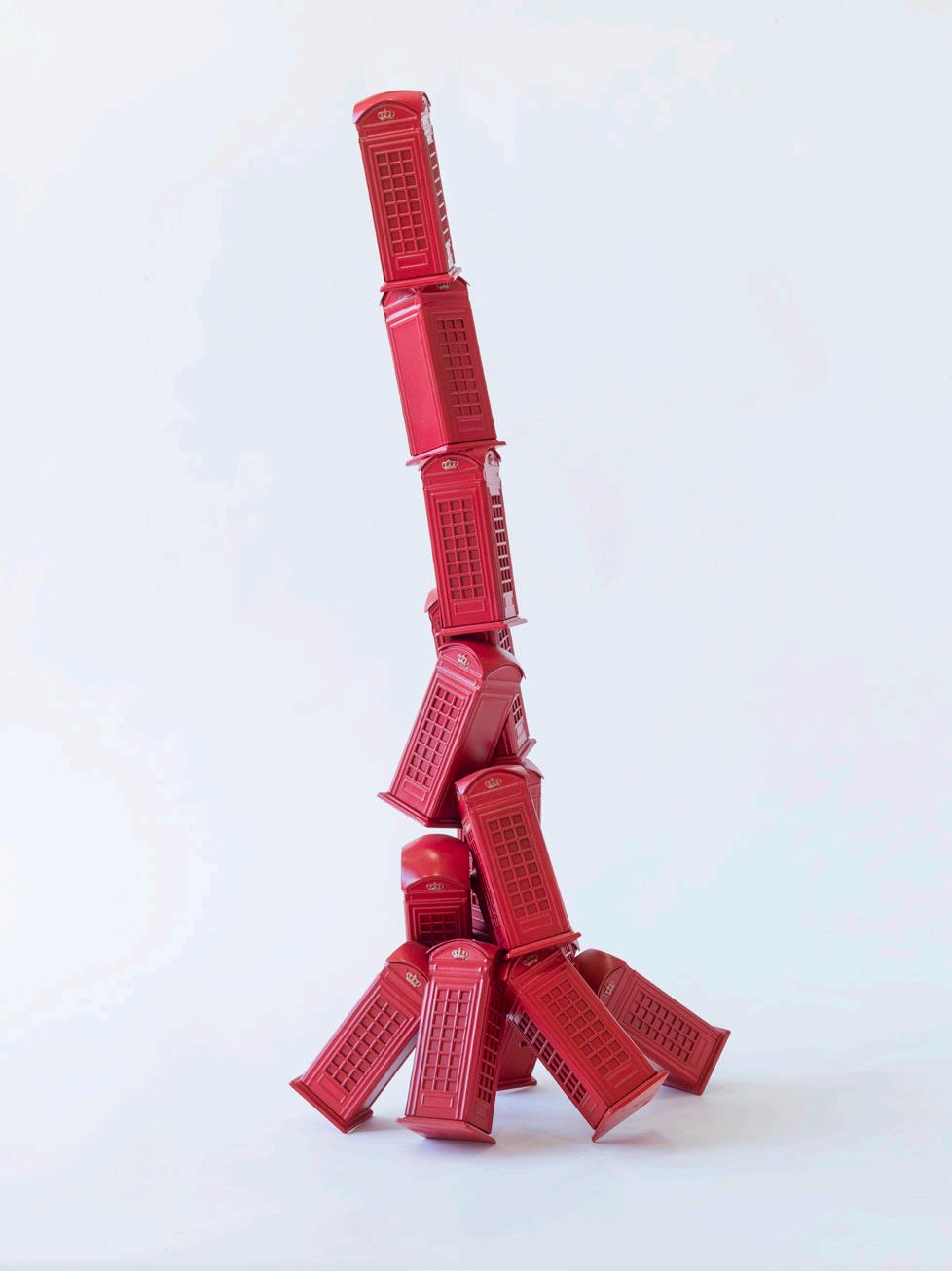

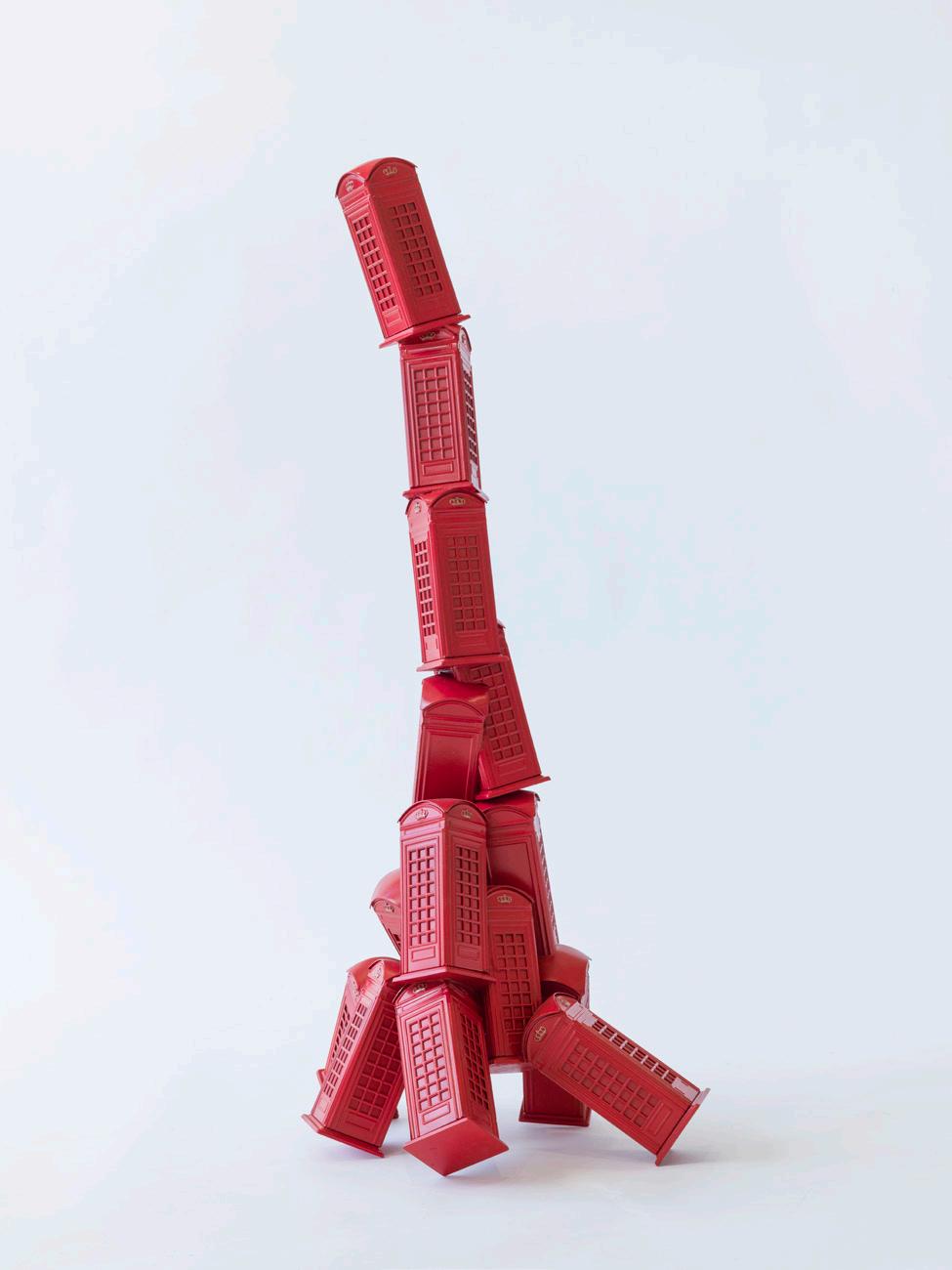

Telephone Box Maquette III

2022, Model for bronze

Edition of 10 18 x 26 x 20 cm

The Oligarch’s Nightmare 2023, Model for bronze Edition of 5 87 x 60 x 60 cm

Hommage au Chaffeur de la

Camionnette Blanche

2023, Model for bronze Edition of 5 99 x 38.5 x 8.5 cm

Hommage au Chaffeur de la

Camionnette Blanche

2023, Model for bronze Edition of 5 99 x 38.5 x 8.5 cm

Unique

95 x 89 x 96 cm each

Our thanks go to David Mach for all his hard work in preparing and installing this ambitious exhibition. We are grateful also for the help and support of David’s partner Lindsay Gibb & his assistant and model-maker Karen Murat. Further impressive models created in painstaking detail were made by - Patrick Milne, Adrian Moakes, & Jeremy Butler. Installing Heavy Metal was also a feat of colloboration and we are grateful to all those that helped including: Kim & Ana Larsen, Geoff Stainethorpe, Alan Campbell, Harriet Selka, Maaike Takens, Toni Gallagher, Alison Harper, Anna Curtz-Price & Louis Loveless.

Our thanks also go to all those at Pangolin Editions who helped translate Temple at Tyre and the Darlington Train Maquette so beautifully into bronze and to Steve Russell Studios for their skillful photography.

This catalogue has been published to accompany:

David Mach: Heavy Metal

25 January - 25 March 2023

Pangolin London Sculpture Gallery Kings Place, 90 York Way London, N1 9AG

T: 020 7520 1480

E: gallery@pangolinlondon.com www.pangolinlondon.com

PANGOLIN LONDON SCULPTURE GALLERY

KINGS PLACE, 90 YORK WAY, LONDON N1 9AG

T: 020 7520 1480 E: gallery@pangolinlondon.com