The watch magazine would like to express its gratitude to the following members of the Porter-Gaud community for their help with this semester’s publication:

Bennett Adkinson, Paul Baran, Brian Champlin, Price Chariker, Jordan Click, Gracie Coleman, Samantha Fisk, Barbara Harpe, Brent Hilpert, Sadye Krell, Tori Kuchler, Joseph Michaels, David Myer, Brink Norton, Fran Ridgell, Joe Romano, Anna Smith, Celeste Webster, and Amber Wilsondebriano.

Thank you all!

We could not be a magazine without your involvement.

Table Of Contents

Towing the Line—Or Lying

At what point does a lie go too far?

Lucia Spiotta

Still Believe Your Eyes When It Comes to AI?

Who (or what) created these works of art?

Benjamin Zielke

Tipflation: A Gratuity Epidemic

Where is my tip for this article?

Kevin Pham

What Were Beauty Standards Made for?

Diving deep into the growing desire to remain young.

Mirabelle Cutler

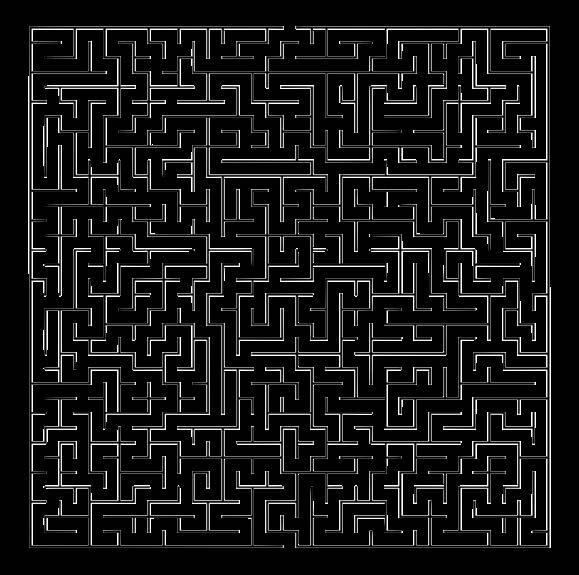

Solve Your Way to Summer!

Reach the end to find your respite from school.

Gracie Keogh

The Odyssey

A semester in DC taught me the importance of reflection.

Hampton Brooker

A) College Board Isn’t the Best Answer

The future of education cannot be multiple choice.

Benjamin Zielke

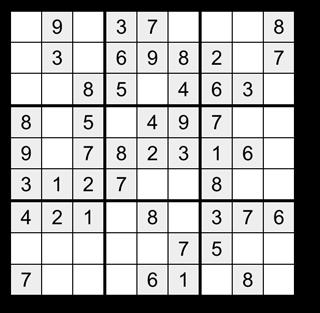

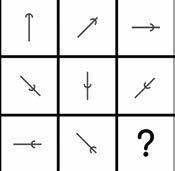

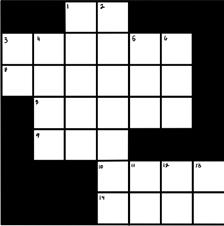

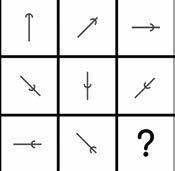

Puzzle Me This:

Solve these sequence puzzles to test your wit.

Charlie Sidney

Affirming in Equity

Affirmative Action in college admissions.

Abby Comer

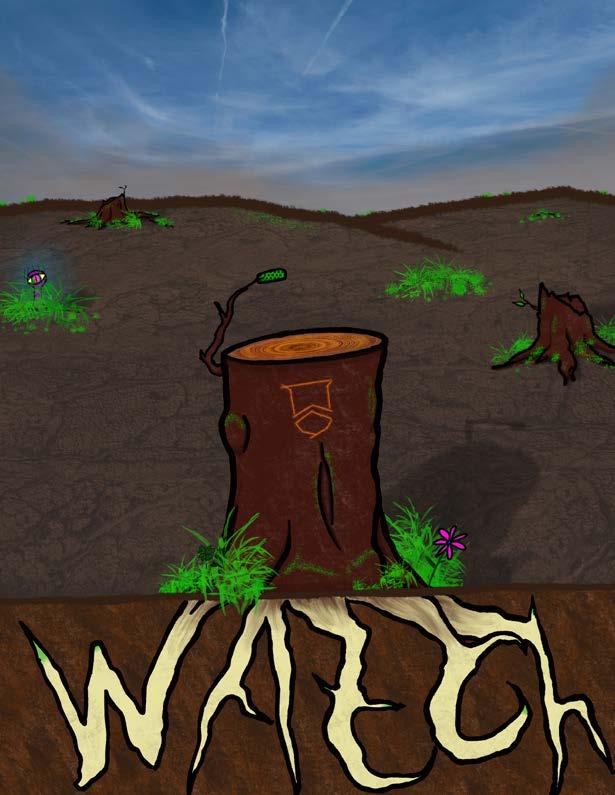

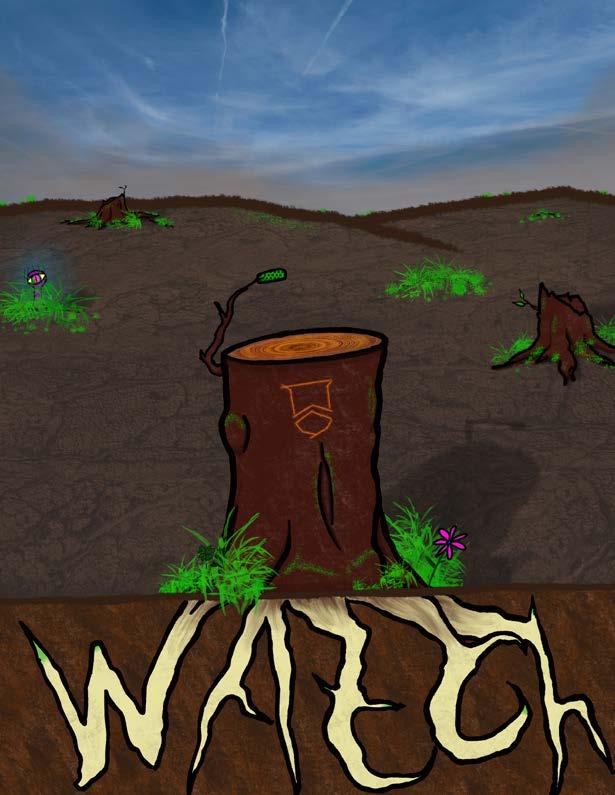

Front and back cover art by Art Director Anderson Toole.

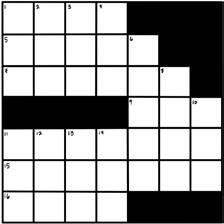

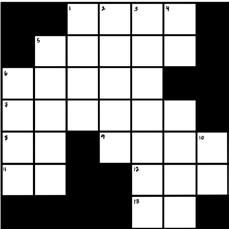

Crosswords

This time with a key (you’re welcome)!

Abby Comer

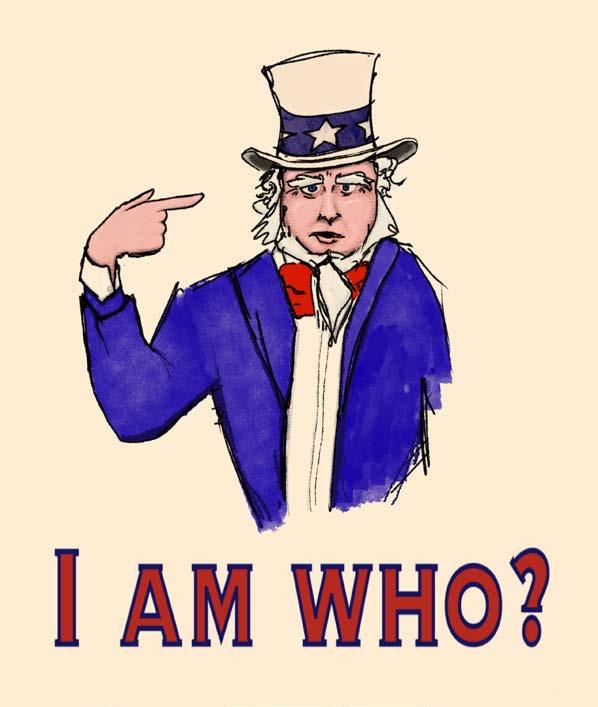

E Pluribus Problem

What defines an American anymore?

Anderson Toole

Connections

Can you make the links that matter?

Mirabelle Cutler and Kevin Pham

We are Living in a Dystopian Movie

Our government is failing us, but why are our schools?

Gracie Keogh

Teacher Trivia

How well do you know your teachers?

Hampton Brooker and Mirabelle Cutler

2 4 6 8 10 12 14 20 24 26 30 32 34 18

Gracie Keogh - Managing Editor

Nina Ziff - Head Publisher

Anderson Toole - Art Director

Kevin Pham - Publisher

Charlie Sidney - Publisher

Abby Comer - Section Editor

Benjamin Zielke - Section Editor

Hampton Brooker - Staff Writer

Mirabelle Cutler - Staff Writer

Lucia Spiotta - Staff Writer

Mrs. Abby Laskodi - Faculty Advisor

Ms. Sarah Romano - Faculty Advisor

Mr. Childs Smith - Faculty Advisor

A special THANKS! to Brian Champlin and the rest of Avondale Station 10 for your kindness and generosity in sharing your station with us at the magazine.

Our Wonderful Staff:

Towing the Line—Or Lying

At what point does a lie go too far?

by Lucia Spiotta

You get invited to a friend’s house for dinner for the very first time. You meet the dad, dog, and aunt from out of town. Then, there you are, seated next to your friend and their boisterous little brother at the table when dinner comes out. Taking that first bite, you find the food to be… bland? It’s unsavory and, honestly, a little bit undercooked. Noticing your face twinge in response, her mom—who had spent the whole afternoon cooking—asks if you like the food.

What do you say?

The truth? A lie? Or perhaps something in between?

One study shows 60% of people can not go more than ten minutes without telling a lie.

Not too long after we first learn how to use language to express our thoughts, we feel tempted to embellish a little. Begging the question: when is it okay to lie?

This moral dilemma troubles many people, and there are a variety of different responses. Some, like philosopher Immanuel Kant, approach it in moral absolutes, believing that under no circumstances is lying acceptable. Kant argues that people must be bound by the truth and have an imperative to do so—even if a murderer asks where your friend is. Utilitarianists condone smaller deceptions like “white lies,” as long as they benefit the good of the majority. However, what defines a lie as “white” or otherwise is subjective.

In the 14th century, the phrase “white lie” was first coined and has been plaguing people’s morals since. In Western culture, white represents morality and purity due to its symbolic usage in many world religions, which is ironic considering that the very debate over white lies struggles to determine if they are immoral or not. It would feel awful if someone told you that you smelled like a middle schooler who forgot deodorant, your little brother was an idiot, or you were having a bad hair day. So, commonly, harmless lies (and omissions) are used to protect someone else’s feelings.

A study by the journal Nature Neuroscience discovered that the more someone lies, the more they feel inclined to repeat and escalate the level of their lies, because, through repetition, the misbehavior becomes easier and easier to do. Coupled with the fact that, on average, people can only detect a lie 54% of the time, the truth can seem easy to throw aside in exchange for a lie.

Unfortunately, new misinformation spreads through the internet and news media outlets every day. Considering the fact that social media aims to entertain, its content does not always convey the whole (or even partial) truth. For example, when contact with the infamous Titan submersible was lost last June, many people turned to TikTok for updates and found information that was simply untrue. A video purported to be of the final screams of the submarine’s passengers reached over 4.9 million views in just ten days; except, this audio was actually from the video game Five Nights at Freddy’s. Unfortunately, this misinterpretation went viral faster than the corroborated, truthful information regarding the incident: just one of many instances in which social media quickly spreads inaccurate news.

Social media quickly spreads news, just not the truth.

A study done by MIT found that novelty is a large factor in the rapidfire spread of false news. Due to exaggerations and catchy information, people may feel drawn to the stories due to a phenomenon called sensationalism. This same phenomenon can be seen in gossip. Have you ever heard a rumor so wild and hilarious that it stuck with you, even though it was likely untrue? In both cases, the aspect of surprise and over the top details draws people in, despite its inaccuracy. However, false news can lead to unnecessary confusion and muddy information channels. The dissemination of unreliable news has grown enormously, making the truth even more important than ever. An additional concern over stretching the truth can involve people acting on a white lie told to them that leads to real embarrassesment later on. Would that not, then, make the lie unethical? After all, it would still end up eventually hurting

the person. In such cases, note how a lie could go from being prosocial to antisocial. Let’s say your friend is wearing a bad outfit. Telling them that the outfit looks good will please them in the moment, but it could become embarrassing after wearing that outfit in front of a crowd. In this instance, it would be better to just tell the truth.

According to a study given by the University of Massachusetts, 60% of people cannot go more than ten minutes without telling a lie. Likewise, if you fib only one or two times daily, (which may seem like a small number), when expounded over months and years, it grows to be quite large. Even though lying about your weekend plans, a grade on a test or retelling an untruthful rumor can be fun in the moment, in the long run, the accumulation of all these falsehoods can be sizable. To combat the growing number of lies spreading through social media and by word of mouth, consider simple solution: telling the truth while keeping empathy in mind.

Although lies can start small, they have the ability to snowball and impact much larger decisions. Unfortunately, many falsehoods have been perpetuated by prominent figures, including members of the government across both parties. In a world where opinions are so divisive, politicians have stretched the truth for their own benefit; certainly, many candidates in office today have been accused of acting carelessly in regard to the truth. So, with the upcoming election in mind, holding yourself and those around you accountable for the real facts is crucial.

Telling the truth does not have to be blunt or mean. Matters can be handled in a more caring, empathetic manner. There is a delicate balance between truth and kindness, which must be taken into account when considering whether or not to lie. We should use our language to not only uplift others but also stay true to ourselves in this society where it can be all too easy to hide behind falsehoods.

6 7

Art by Gracie Coleman

5. LEFT is AI because of the misplaced heart and the odd shapes on the wall. This image does a great job of of reproducing the overall look and feel but misses some of the mbolicsy choices of the original—the halved nature of the original.

4. RIGHT is AI because the kitchen tools look oddly shaped, and the the pot is in a weird spot. Notice the glitching on the spatula—the AI clearly doesn’t understand what it is.

3. RIGHT is AI because the icons are unclear in what they represent, and the colored pencils in the background don’t serve a purpose. This image shows it was made by a prompt, because the user likely asked for it to be created in colored pencil but the AI drew in colored pencils, misinterpreting the statement.

2. RIGHT is AI because the camera is placed below the Apple logo, and it’s unclear what the lines represent. This shows a lack of understanding for what an iPhone actually looks like.

1. LEFT is AI because the entire image looks haphazard, and the supports overlap one another. It lacks an understanding of the structure.

8 9 Do You Still Believe Your Eyes When It Comes to AI? Did a human

AI create these works of art? Very Easy Easy Medium 1 2 3 Difficult Very Difficult ANSWERS 4 5

or

Tipflation: A Gratuity Epidemic

Where’s my tip for this article?

By Kevin Pham

We all know the infamous iPad on a swivel intended for a singular purpose: completing your transaction. But, first, you must tip. So it glares at you forebodingly with its three options: 15%, 20%, and 25%.

For a typical $5 latte, I think many can agree that the option to pay an extra 15–25% feels unnecessary. Tipping culture in the United States has become overwhelming, and the obtrusive iPad and accompanying employee staring you down has transformed the experience from tipping to “guilt-tripping.”

a greater incentive to tip in a society that is already overly saturated with an absurd amount of such gratuities. It begins to become clearer how overtipping has become normalized as we have created a culture in which we are highly encouraged to tip. However, at the end of the day, it is an unsustainable expectation for American citizens to overpay for daily purchases. A prime example of this trend is seen in a Forbes article that describes a person having to pay extra gratuity to the local butcher as a required service charge. I have shared many of these absurd experiences in my personal life as someone who has paid five times more than the price they were quoted for chocolate ice cream and has paid an extra 50% for a small iced coffee. Many, including myself, feel as if it’s a cycle that has saturated modern society to the point where it’s inescapable.

Whether ordering black coffee for breakfast, or ice cream for dessert, almost every food service you encounter these days comes with an additional price known as a gratuity. Not to mention the psychic price of that awkward silence between you and the employee when contemplating the intentionally small “no tip” button on the monitor. Because all too often, it feels like not tipping (even when only minimal service was given) is not an option anymore—a phenomenon that news sources, such as Vox and Forbes, have aptly named “tipflation.”

The majority of Americans agree there needs to be an end to the emphasis on tipping, along with the stigma of being criticized for choosing not to tip. My recent experience working as a barista led me to pay more attention to this topic because I can recall moments knowing that someone felt forced to tip me $2 for a croissant that I simply got out of a plastic pouch and heated up. Not everyone, however, is on the same page—take, for instance, this barista sharing her perspective on Vox: “‘I’ve worked as a server, and servers keep most of their tips even though they don’t make the food,’ she said. ‘People like to say with baristas it’s a quick transaction, but the difference is we’re actually producing something for you.’” She has a valid perspective on the amount of work baristas have to tend to, but the point the person implies of being required or entitled to make and serve food is taken out of proportion and is entirely subjective. The mannerisms and experience that are required in both of these jobs—cook and barista—are unique and of different difficulty levels. Therefore, victimizing the title of being a barista and framing it as some sort of charity case for tips further creates

As a result, tipping is no longer being seen as a way to recognize excellent service. With such expectations to tip, some establishments have even implemented ways to require tipping by installing a premade price on your bill, thus shifting what has been a culture of gratitude to one marked by discomfort or maybe even anger. In addition to the spread of a service fee, more and more businesses are now asking for a tip option. In a Forbes magazine article titled “The Tipping Economy: Is Tipping Out Of Control?’’ the writer describes his annoyance with being constantly presented with tip options everywhere he goes: “It’s no longer about anyone (servers, taxi drivers, hotel staff, etc.) receiving a tip for good service [...] Today, customers are being pushed to tip higher numbers, almost to the point of making customers feel uncomfortable.” Needless to say, tipping is growing exponentially, not because it offers a reward for outstanding individuals, but instead to cater to growing societal expectations.

What was once a way of showing gratitude toward your server is now an awkward moment of shame for those who press the “no tip” button

art showing you the options 15%, 20%, and 25%, along with an intentionally small (read: shameful) “no tip” option in the corner. Try to imagine the interaction of handing a customer the tablet while looking directly at them as they choose whether to tip you for merely taking your order and handing it out the window. Now, imagine that same encounter repeating every two minutes for an entire shift. Each of those ten seconds felt like an eternity.

It’s not only an awkward experience for the customer but also for the person on the other side of the iPad. From my own personal experience, feeling like someone is forced to pay me extra money seems like stealing from them. Some memories of working at the drive-thru Starbucks still haunt me. At the register inside the store, the machines automatically show a tip screen to the customer. The drive-thru requires physically handing the customer a flashy iPad with the generic corporate

Some may argue that baristas “deserve” tips as they essentially manage the entire cafe. While they do manage making the week’s supply of cold brew and drinks for in-store, mobile, and drive-thru orders, all while also taking the person’s order at the register, I don’t necessarily agree that this should come with an automatic gratuity fee. This is especially true in comparison to service employees who are underpaid and not compensated for the work they do. The core of working in jobs such as food and customer service is to make a living, but this necessity cannot be put in conflict with the tension between the worker and the consumer—one wanting extra money and the other hesitant to offer it. This all highlights the question of how much establishments should request, and what jobs should deserve that extra price?

A way to move on from this culture of obsessive tipping is to begin to focus on jobs in which labor should equate to a fee based on gratuity—not fear of judgment. There are

numerous examples of this, but more laborious work such as creating, building, and cleaning need to be considered. Professional cleaners, such as hotel staff, have to be part of a 24-hour rotation. In addition to the expectation of laborious cleaning, maintaining multiple rooms, and ensuring each suite is kept in pristine and clean conditions, these industries are often extremely demanding, resulting in long working hours corresponding with guests. Even though these workers are sometimes tipped for the work they do, it’s usually only when the person staying in the establishment is checking out, meaning that they usually receive one tip for the numerous cycles of cleaning they provide for a single room.

I mention all of this to demonstrate the stark difference in day-to-day expectations with various jobs and the need to bridge that monetary gap through tips in professions that are underpaid. In reality, the person crafting your iced coffee is sure to be exposed to more customers, likely meaning more gratuity, while the person making sure your hotel soapdish isn’t empty and your sheets are washed is typically working behind the scenes and thereby going without. Tipping, at its core, is meant to deliver a message of appreciation for the effort and work an employee has done for you. By evolving this notion into an assumption that that extra 20% is required is toxic; it usurps the significance of why this token of appreciation is even given. It’s gone from a way to say “thank you for a job well done,” to “press this button or seem like a bum.”

10 11

20% 25%

11 10

Art by Anderson Toole

What Were Beauty Standards Made For?

The growing desire to discover the perfect age.

by Mirabelle Cutler

Overwhelmed, Barbie stands alone in a concrete jungle, nothing like the vibrant technicolored Barbie Land to which she’s accustomed. Dispirited by the evident patriarchy of the “real world,” she sits down on a bench in despair, her all-pink rodeo outfit and cowgirl hat a stark opposition to her current state of mind.

After a long moment, she turns to her right and notices down the length of the bench a much older woman sitting nonchalantly with quiet reserve. The woman, in muted clothing, likely in her 80s, is an even starker contrast to Barbie’s flamboyance.

It often seems that, regardless of a woman’s age in life, there is a constant internal, as well as external, pressure to change.

Affected more than she expected to be by the presence of such self-assurance, Barbie tearfully chokes out, “You’re… so beautiful.”

No doubt most of you know the source of this vignette: the crowning cinematic billion-dollar box office movie Barbie that took over last summer in a pink storm.

This small scene, though seemingly fleeting, actually holds much greater relevance than we may think. An older woman, knowing her worth without having to show it, becomes an image of confidence not often seen in film and an inspiring figure for Barbie to behold. Greta Gerwig, the film’s director, related as much in an interview with The New York Times, saying, “If I cut that scene, I don’t know why I’m making this movie. If I don’t have that scene, I don’t know what it is or what I’ve done.”

So why is this scene so essential?

Maybe it is due to the fact that, regardless of a woman’s age in life, there is a constant internal, as well as external, pressure to change. Women get the message that they always need to be something else, whether it’s

older women attempting to appear youthful, younger girls trying to appear older, or even women in the coveted “prime age” not content with their body and constantly comparing themselves to those around them.

All over social media, stories have gone viral of tween girls running rampant in Sephora to buy expensive skincare products originally made for adults. Add this to the ongoing trend of wearing clothing many would deem “too mature,” and it’s clear there is real pressure for young girls to instantly morph into their “prime” state of beauty, whether healthy or not.

It’s well known that young girls have been inundated with unrealistic beauty standards, fashion trends, antiaging products, diets, and a constant slew of damaging messaging. A study from the University of New Hampshire’s Scholar Repository claims,

Overall, the beauty industry has a negative effect on a woman’s self-esteem, body image, and perception of beauty. By using upward comparisons, women are constantly comparing themselves to standards of beauty that society shows to them.

The article goes on to attribute body dysmorphia, negative emotions, eating disorders, and more toxic experiences to the aggressively consumeristic nature of the beauty industry.

Regardless of a woman’s stage in life, she can feel as though she is never enough.

To many, this phenomenon represents the alarming ways in which society is declining. Standards for beauty have always had a substantial presence in culture; they are an integral part of humanity all across the world, with many equating beauty with success and prosperity. In an article in Science Direct, Dimitre Dimitrov notes,

“Beautiful people are considered more successful in their professional and personal life, and beauty is associated with well-being.” As a result, this pressure on one’s physical appearance not only impacts the young, but extends to older women as well, seen in the rapid desperation to prevent the stigma of aging through any means necessary.

Such anxiety is expressed in another pivotal Barbie scene in which America Ferrera, who plays a working single mom in the “real world,” struggles with an existential crisis. Speaking to Barbie on the deep complexity of being a female facing reality, she tearfully laments, “It is literally impossible to be a woman: you have to be thin, but not too thin. And you can never say you want to be thin. You have to say you want to be healthy, but also you have to be thin… You have to never get old, never be rude, never show off, never be selfish, never fall down, never fail, never show fear, never get out of line.”

This scene was quickly heralded as the centerpiece of the movie. I remember sitting in a packed theater last summer with my friends, noticing that women all around the room were nodding in agreement, a quiet sense of connection and shared experience settling over so many in the audience.

Art by Sadye Krell

Art by Sadye Krell

For this problem persists around the world. Globally, there seems to be a heavy pressure, especially on women, to prevent any form of aging, including, of course, preventative surgical measures; the use of botox, retinoid, collagen, and chemicals now seem the norm in order to prevent the natural aging process and somehow impossibly maintain a “perfect” stage, all in an attempt to prevent the inevitable. Despite using contrasting approaches, generations of young girls and women on both ends of the spectrum attempt to alter their current phase in life through permanent physical measures.

With age comes self-acceptance through experiences that strengthen our empathy and character.

What Ferrera’s speech reflects so clearly is that regardless of a woman’s stage in life, it can seem as though she is never enough.

But there is power in realizing the beauty of aging, acknowledging it, and proudly welcoming it as a healthy and realistic part of life. With age comes self-acceptance through experiences that strengthen our empathy and character.

By mere appearance, that older woman sitting to the right of Barbie on the bench seems to contrast everything our pink protagonist represents: youth, vitality, vivaciousness. But in reality, in the real world, even in that concrete jungle where a fading patriarchy may still partially exist, she exudes strength, integrity, and peace within.

They soon share a knowing laugh that emphasizes as much, proving Barbie’s compliment correct: she is “so beautiful,” and the woman, illustrating her enviable satisfaction with her age, responds confidently, “ I know! ”

12 13

Solve

Summer! Start! Finish! 14 15

Your Way to

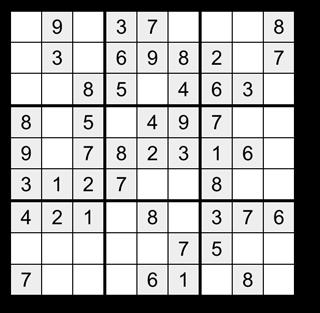

Courtesy of Sudoku Web

Courtesy of Maze Generator

The Odyssey

How a semester in DC taught me

the importance of reflection.

By Hampton Brooker

Earlier this year, about halfway through the fall semester, we were told that an entire day of school would be blocked off for what they called “The Odyssey.”

Six weeks in, and I had just settled into life in Washington DC at a program called the School for Ethics and Global Leadership (SEGL). I had been spending the semester thus far attending classes, meeting with important change makers, and experiencing life in our nation’s Capitol. As if this wasn’t unconventional enough for me, I had been living without my phone. Just when I thought I had adjusted to losing this artificial limb, I was being told that my life was about to change, once again.

Noah, the head of the school, soon explained that the objective of The Odyssey was for us to have a whole day to reflect, something we very rarely have time to do in our busy high school lives. Behind the scenes, the teachers and advisors had been learning about our interests, strengths, and weaknesses for the first month and a half of school.

For each of us 24 students, the teachers had curated a journey through DC’s museums, monuments, and gardens with specific pieces of art and prompts that were unique to our established profiles.

For this adventure, we were given a prompt to evoke our reflection and the initial address of the three destinations where we would go to throughout the day.

During the first two months without a phone, my view of direction and everyday life changed completely: no communication with family and friends, no GoogleMaps, no ApplePay, no camera to scan QR codes, and no connection whatsoever.

At this point, halfway through the semester, I had already adapted to this new way of life. But, because The Odyssey was an individual experience away from the dorms, we were given back our phones for the day—for use only in an emergency and to receive calls from our advisor with the next address of our journeys. This meant that we had to use what we were taught about the map of DC, a relatively simple grid of four sections, with the nearby

What does this say about you and how you want to live your life?

Capitol directly in the center. Santi, the residential advisor, directed that after each hour passed at a set destination, we would receive a call from our advisor to provide us with the address of the next location.

I fidgeted with the sleeve of my sweater while awaiting my turn to leave the dorm, impatiently watching as each student was called outside. I could not wait to find out what would be my first destination, and as more and more of my peers left the residence, I wondered how the day would go. I vowed to be completely invested in this opportunity of departure from the dependence on my phone in order to fully reflect on each destination. I trusted that the experience would only be impactful if I followed the rules of The Odyssey. Finally, my name was called.

I approached Caila, my precalculus teacher who, smiling, handed me an envelope with the slips of paper containing my prompts alongside a sheet that featured SEGL’s famous question: What does this say about you and how you want to live your life? Caila then gave me the address of my first location: the East side of the National Gallery of Art. I was off.

Twenty minutes later, after strolling by the Supreme Court and Capitol building, I had made it to the museum. The painting I was sent to view—“Orchestrating a Blooming Desert” by Steven Yazzie—evoked within me thoughts of climate change throughout the world; its selection felt personalized. I had often discussed my passion for the environment in class and with friends, and had done a few projects on plastic pollution. Observing the painting, I journaled a few pages about what I could do to help protect my environment, and then left for my next destination.

My second assigned location was the National Portrait Gallery, specifically to examine a portrait of Sojourner Truth, the well-known Black abolitionist. I initially wandered through the gallery to take in the historical figures represented in the museum, finally approaching a dark room that held the small, notecard-sized portrait. Sojourner Truth sat nobly at a table with flowers, wearing a long black dress and a scarf, gazing sullenly at the camera. Looking closely, I saw a statement printed below the portrait, stating, “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance.”

This piece was more challenging for me to make a connection with. After some time, I realized I was sent to this location because I often discussed my discontent with how people saw me as a Southerner. There was only

one other person from the south (Tennessee) during my semester. The other 22 students were from the North, West, or abroad. I suspected that this surely impacted how many people saw me. After getting to know many of my classmates, my suspicions were confirmed; I learned that they had (like most people) placed stereotypes on me that I quickly proved wrong. Remembering this expierience, I became inspired by Truth’s photo. At the time of its creation, the purpose of Sojourner Truth’s portrait was to disprove the horrible stereotypes placed on African Americans and generate interest in funding her anti-slavery movement. Facing Sojourner Truth, I realized I needed to worry less about how others see me. I will disprove them with my words.

My final stop was by far the most emotional. It caused me to reflect on the biggest struggle I had encountered during my time in DC thus far: homesickness. I found a spot on a bench along the water of the tidal basin, gazing across the way towards the Lincoln Memorial. In group discussions, class projects, and peer conversations, I had often shared about my love for the Charleston harbor and childhood memories of boating with my family. I knew this location on the Potomac River had been chosen for me due to this reason. Sitting by the water’s edge, I reflected for a moment on what I could learn from this sight before unfolding the poem from inside the envelope. It was about a mother saying goodbye to her daughter, using the metaphor of a child’s first time riding a bike without training wheels. Overcome with homesickness, my eyes began to swell with tears. I went against the rules and snapped a selfie on my phone and sent it to my mom, “I love how this is where they sent me for my last stop, reminds me of home.” When I returned home two months later, I saw that my mom had framed it in our kitchen.

Later that day, everyone returned from their own Odysseys, and we circled up in the common room to hold a Quakerstyle discussion. In the Quaker tradition, everyone is invited to speak—but only once and for however long they would like; if a period of silence endures uninterrupted for roughly five minutes, it is understood that the discussion has come to its natural end. After everything each of us had encountered and thought about that day, there was much to be said, and the discussion went on for over two hours. Honestly, it was mind boggling. Despite all of my reflection and personal connection to each of the art pieces, I felt that other students had experienced an even more impactful outing: Brendan had mistakenly veered off the path of his Odyssey and saw a young father and his son walking towards the Capitol, which reminded him of his childhood dreams of living in DC to become an important politician. Jake, a film-lover, was inspired to make his own short film after visiting the Portrait Gallery. Sofia, who felt no connection at all to her destinations, made up her own Odyssey by exploring a nearby garden. Hearing from everyone’s experiences helped me later accept that each of us were impacted individually in uniquely different ways.

It has now been seven months since My Own Odyssey, and not once have I taken the time to reflect as I did that day. The reason for this is that it became more difficult after returning to my busy Charleston life. With more freedom, a phone, and less time, I have not put in the effort to set aside moments specifically for reflection. But despite not giving myself the opportunity for intentional reflection, I know I have learned its importance. I see it in conversations with friends, in class discussions, and at family dinners.

In order to grow, one must look back on the past, accept it, learn from it, and change because of it. True change is entirely self-motivated. It takes time, but it can mean so much for the quality of our lives.

On our last evening at SEGL, nine weeks after our Odysseys, we had our last Quaker-style discussion. The first teacher went, Dr. Patty, my Spanish teacher, and gave a lovely speech that left us hopeful for the future. Then Lizzy, my US history teacher, spoke a humorous, yet sentimental goodbye. Like the first Quaker discussion, this, too, was emotional and enlightening, yet somehow, for me, entirely different. Then, I was reluctant to speak. I feared what everyone would think of me. I worried what I said would not be good enough. But faced with a final chance to speak to the entire community, I felt a sudden urge. I began to speak. Gone were fears of sounding unintelligent compared to my peers. My reflection had prepared me for this, and before I knew it, I had spilled all my emotional goodbyes out to the group, recalling my favorite memories of our semester together. After that, I realized all of the hard work was over, and it was time to return home.

Art by Gracie Coleman

16 17

A) College Board Isn’t the “Best” Answer.

The future of education can’t be multiple choice.

by Benjamin Zielke

For many, it’s an all too-familiar feeling: sitting in a soundless room when, suddenly, the thick packet hits your desk, adorned with its infamous black acorn signifying this year’s College Board creation. You struggle to cut the seal as you reluctantly embark on the 2-to-3-hour journey. #2 pencils tap, papers turn, and TI-84 keys clack as you navigate each multiple- choice question and free-response question like obstacles on a tortuous course.

Undoubtedly, this is the mother of all tests. It’s an exam to gauge whether or not you “get it”––in other words, if you truly understand the content you’ve learned all year. Or, it’s College Board’s best attempt to sum up every moment of your class. In reality, though, it’s an exam not representative of the educational journey you may have experienced (or even wanted to) but rather the journey the College Board wanted you to take.

Now, as we near May, it’s nearly time for us to take the College Board’s exams once again.

College Board assessments are deemed the final secondary education marker for grades 9th-12th. They check for your comprehension of topics on a massive scope: your entire high school education. However, there’s a twist. Though familiar content is presented in these examinations, the goal of the test is not to see how well you understand these concepts but how well you can apply the knowledge. It’s a skill called aptitude. Your goal is to get the deemed “best answer”––a completely different approach than other tests you may have taken—focusing solely on comprehension. But is this the “best” way to measure our knowledge?

In 1899, the College Entrance Examination Board was founded by 12 universities, all of which shared a common goal of improving education globally. Their shared motivation could be summarized by a singular word: standardization. This caused New England boarding schools to adopt a uniform curriculum to push a standardized college admission

process as a whole. As a result, in 1901, College Boardadministered exams were born. This event represented a significant shift in the country’s education as it delineated what students needed to know within given subject areas to master them, leaving this new institution in quite a position of influence.

The side effect, though, was a change in the way we see education. Embedded in the very definition, the broad term garners some meaning—an enlightening experience. This seems to indicate how education, while necessary for a society to maintain order, is an experience in which one learns about the world. And, these experiences are, well, experiential—they cannot be repeated again and again for each individual, setting up an expectation of similar outcomes. Education is an individual pursuit; it differs from person to person. Although we must have some assessment in place to serve as a baseline for whether a student

was a professor of psychology at Princeton and, most importantly, a eugenicist (one who believes that to improve humans’ genetic quality, we must alter human gene pools by excluding people deemed “inferior” and promoting those judged superior). Brigham’s aid in administering these intelligence tests for over two million recruits led him to devise the version he offered to students at Princeton University and Cooper Union.

Eventually, this test evolved into the SAT, which debuted in 1926 and claimed to focus more on assessing aptitude than received knowledge. This concept seemed good in theory: If a student’s innate ability to learn could be understood, predictions could be made about where their education might be headed. However, this is where the game begins.

understands something, we cannot allow such an exam to define a student’s potential or educational journey for the long term. The mindset of having material to teach students this process, assess them, and constantly repeat it is what has contributed to a waning desire to learn over the years.

The College Board, however, embodies this stale process of monotonous memorization and regurgitation, except it must be done entirely their way to secure a high score. A large part of taking a College Board exam is understanding what they want and exactly how they want it: any other way is incorrect. In pursuing standardization, the desires one has for education don’t

Ironically enough, this regimented approach by the College Board stems from IQ tests administered with soldiers. Carl Brigham, the father of the SAT,

The SAT and AP tests morphed into a gate barring admissions to college and act as markers for comparison among students. You have to take the SAT to even be considered, and your performance directly impacts your admissions. This is Brigham’s standardization vision, and to this day, those who are deemed intellectually “superior” go to elite universities, while those who are not attend less elite schools. The issue? The SAT has created a world in which a single test score on a Saturday morning is seen with massive weight, becoming one of the most prominent indicators of your potential success in college. It has been accepted because it’s the only way to put students across America into somewhat distinct categories. However, this also entails that often only those who can perform the very “best” on the College Board’s SAT can get into an elite school.

However, these supposedly intellectual superiors have often just gotten very good at playing College Board’s game. This is mainly because they usually have more money, resources, and opportunities. While marketed as a test to engage inherent knowledge, the SAT requires a lot of studying of SAT-type question—that is, AP/SAT questions are something new to learn within themselves. Additionally, only decent test takers can truly succeed, as those who are too slow or buckle under pressure will struggle. This leads to many students (and their parents) hiring tutors, paying for courses and prep books, and dedicating time to study, inherently putting those who do not have these resources in a deficit. As a result, this sets them up to be deemed “intellectually inferior.” In reality, though, those who may truly be intelligent and desire to

18 19

Art by Price Chariker

pursue a higher education go unnoticed. Furthermore, the SAT can allegedly assess the ability to learn but cannot evaluate the desire to learn. Yet, these issues also beg the question: Why does a test touted as the marker for your inherent abilities require you to augment your skills to succeed considerably? It’s just a different monster of its own—a different test from what students have done previously in their education. It’s a game you have to learn to play, and your success determines what school you attend, affecting your very life trajectory.

No test can gauge every student’s ability to learn.

This was the reality of standardized testing until four years ago, before COVID-19 and the pivotal “test-optional” movement. This was yet another change in societal dynamics, merely to aid in avoiding exposure during the pandemic. However, the shift conveniently coincided with underlying concerns with the admissions process recognized by colleges. So then it’s not so strange that every school decided to allow the test-optional choice to stick around with the pandemic in the rearview and normalcy restored—quite frankly, the process was unfair.

The truth is, no test can gauge every student’s ability to learn—it’s something you define as you pursue your education, and it cannot be predicted by a mere test score. Certainly, too, a singular snapshot cannot have such a play into where you spend the next four years of your life. In this sense, standardized tests are on a weird spectrum, claiming to define one’s academic ability while, in reality, merely showcasing how well a student understands concepts they’ve learned specifically for the SAT and anticipating its “tricks.” These tests are designed against us, touting their use of words like “the best option” or “which is NOT correct” to flat-out mislead you on a question, claiming it’s to test you on how you adapt.

In reality, however, does it even matter whether or not you can play the College Board’s game? The assessment of one’s education should convey an academic journey, and a standardized evaluation must be used to see where one currently stands. However, it cannot be the deciding factor of whether or not they are worthy to pursue higher education.

Thankfully, the SAT and AP exams have begun to have less and less weight in the admission process due to colleges’ recognition that one’s intellect and aptitude can’t be based on just a score. Instead, we should have free choice to demonstrate academic ability—the true spark of the test-optional movement. Colleges have started

looking more into course grades, college essays, and tests in specific subject areas (showing your strengths)—not just a singular test created years ago to narrow down the most intelligent students not through intellectual ability but rather how well they understand the SAT—a pursuit that punishes those without the same opportunities others may have.

Clearly, the College Board’s privatized and monopolized grasp of standardized testing is beginning to loosen. However, that’s not stopping them from wanting the old way back.

In March 2023, the beginning of the College Board’s digital era took shape. For many, this seemed merely a technological shift for the company, updating the decadeold #2 pencils. Behind the scenes, though, something far different was afoot. The test marked a crucial shift in the SAT, changing the test from 3 hours and 15 minutes to 2 hours and 14 minutes, making it a full hour shorter. However, in a test designed against you, why make it shorter? The answer is simple: more people will want to take it, and increasing sales for the college board after the test-optional movement will drastically hurt an individual’s testing. More than anything, this showcases the flaws of privatized education—when profits are put before adequately “assessing” students.

But wait—isn’t the College Board a nonprofit?

Despite being a 501(c)3 nonprofit, the College Board made over $1.1 billion in 2019, and where this sum of revenue goes is of genuine concern. The nature of being a nonprofit means there must be fiscal transparency. However, these financial records are private and difficult to come by, showing deep concern about where this money might go. Regarding compensation for executives, it’s been reported that the CEO made $1.67 million dollars in 2019, begging the question: where’s the money going, and is the College Board even a nonprofit?

This looks even worse in light of the College Board increasing its fees within its testing practices over the years. Essentially, there’s a price tag at every corner— you have to pay $60 for each SAT, $13 to view a list of question types and if questions were answered correctly or incorrectly, $15 to register late, $30 to verify scores are correct, $55 to verify an essay was graded correctly, and most painfully, $12 per college after the first four scores are sent.

The motivations of the College Board are painfully unclear—are they truly helping the good of education by hiking prices and altering test difficulty to drive sales? The answer is no. A privatized company with vague claims

of being a nonprofit cannot handle such a large part of assigning you to an intellectual bracket, and determining where you will study for the next four years, which no doubt affects your entire future. It’s no wonder it took COVID, a global cataclysmic event, to do away with decades of required standardized testing. The company has become something much more than its initial vision of standardization.

The solution, then, is simple. We cannot allow a privatized institution to monopolize the education sector just because they claim to have noble pursuits and are one of the few who offer the services needed for schools. We need to be given more of a choice, so we can start seeing education through a lens of bettering education for students and more seriousness as a whole. The influencers of education need to want to make students discover new ideas and what interests them, assessing more than one level of achievement and aptitude to tell a story about who they are as a learners. While we must standardize to interpret, we

cannot use that as the actual marker. This is something that colleges and universities are becoming aware of, but the College Board still wants to do things the old way.

Ideally, most of all, we need an American government to step in on what’s happening. We need a federal agency to replace the College Board’s position and seek national advancement of American education over financial concerns. Additionally, we need to end the game we play within both the college process and the educational sector altogether based on the notion that a single exam is the marker of your intellectual ability. Though getting an idea of what you can learn/have learned is crucial, we’ve shaped a society in which comparing SAT scores puts people above others. Tests are a tool to assess but not to define and label. We cannot allow an institution to have such a stake in education, demoralizing those who do not meet its misleading marks. We must shape the questions of tomorrow around the learners of today. But one thing is for sure. The College Board isn’t the answer.

The

Time There Was No “Best” Answer.

To see just how the College Board tries to “trick” students, let’s take a look at one of the instances College Board made the hardest SAT question:

In 1982, the writers of the SAT, aspiring to push the boundaries of discovering one’s aptitude, made the hardest SAT question to date. Intriguingly, it was based on a confusing paradox that, to this day, still befuddles many. The paradox goes something like this:

Two quarters touching one another are placed flat on a table. One coin is held stationary while the other is revolved around it, with the edges kept in contact for the entire revolution. When the moving quarter returns to its starting location, how many full rotations has it made?

Intuitively, many would suspect a single rotation of the moving quarter, as its circumference is three inches around. So, since the quarter moves along the same distance as its own circumference it must rotate only once. However, the answer is actually two rotations as if the distance of the circumference of a quarter was put in a straight line, the quater would rotate twice. For many, though this doesn’t make sense. Needless to say, it was a hard question to choose.

Here’s the College Board’s take:

The radius of circle A is ⅓ the radius of circle B. Circle A rolls around circle B until it returns to its starting position. How many revolutions of circle A are there in total?

a) 3/2

b) 3

c) 6

d) 9/2

e) 9

If you chose option B, congratulations—you, like many other students across America, chose College Board’s “best” answer. Using the same intuitive logic as in the paradox, we reason B is three times longer around its perimeter than A. So we then believe the smaller circle could “unwrap” itself exactly three times to encase the larger one. “3,” then was the intended multiple-choice answer. However, similar to the confusing answer of the paradox, circle A would actually make four rotations on its trip (one more than we would expect). It was an answer so confusing that the test writers’ didn’t even include the correct option among the possible answers. This resulted in 300,000 student exams being rescored and showed just how much College Board was trying to trick test takers.

20 21

Affirming in Equity

Why we need Affirmative

Action in college admissions.

by Abby Comer

In 1995, Jennifer Gratz applied to the University of Michigan’s College of Literature, Science, and the Arts as a Michigan resident. She, along with her friend Patrick Hamacher—both of whom are Caucasian—were denied admission. Though they were qualified, at least according to their SAT scores and GPAs, they were nevertheless not “competitive enough” applicants by the college’s admissions department. Since they both believed that they should have been accepted, they assumed that their rejections were due to their race rather than their qualifying academic credentials. In what became the landmark case known as Gratz v. Bollinger, they both sued under the pretense that “holding seats” for certain minority groups violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The abolition of Affirmative Action would lead to more literal equality because everyone would be compared to the exact same standard, but this would take away equity in college admissions as well.

By no means was this the first case that challenged Affirmative Action in college admissions. After the 1978 case California v. Bakke deemed California’s quota system unconstitutional, it was only a matter of time before Proposition 209 passed (which it did in 1996), banning such considerations of race, ethnicity, or sex in public employment, contracting, and education. The argument against Affirmative Action held that these “quota” systems, such as that used by California schools in their admissions policy, directly discriminated against all races, reducing individuals to spots to be filled without recognizing the fullness of their character.

However, unlike Proposition 209 in 1996, the Supreme Court supported the consideration of race in college admissions in the Gratz v. Bollinger case in 2003 with a 6-3 vote. But this case set a new precedent in the path towards abolishing Affirmative Action because it established that such policies hurt America’s white population. Thus, Gratz v. Bollinger reframed Affirmative Action to no longer represent the protection of underrepresented groups, but rather the suppression

of those already in the majority. This precedent led to the Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) v. Harvard and SFFA v. UNC cases of 2023 (nominally consolidated into SFFA v. Harvard) that abolished Affirmative Action in college admissions once and for all.

Affirmative Action’s goal is to create equal opportunities for people of all races, but it’s impossible to reach equality without supporting those who have an inherent disadvantage—members of racial minorities, historically speaking. This equality is reached through the process of equity, providing advantages to those who are disadvantaged. In college admissions, this measure equates to allowing the consideration of race as a means of explaining some gap or otherwise mitigating circumstances in an application—often due to high school enrollment, income, family commitments, and more—that top-tier colleges and universities have come to expect. The abolition of Affirmative Action would lead to more literal equality because everyone would be compared to the exact same standard, but this would take away equity in college admissions as well. Those application gaps now matter, and only those who are privileged enough to fill those gaps have the ability to get enrolled in prestigious universities. In a perfect world, everyone being held to the same standard would truly lead to equality, but without the support of equity, there is no way of truly achieving equality. So then, it can be understood that arguments for or against Affirmative Action are really just arguments of equity vs. equality in college admissions.

But first, a definition. According to the Cornell Legal Information Institute, Affirmative Action is defined as: “a set of procedures designed to eliminate unlawful discrimination among applicants, remedy the results of such prior discrimination, and prevent such discrimination in the future.” Additionally, it is important to recognize the two legal documents used to justify that Affirmative Action is unconstitutional: the Fourteenth Amendment claiming that all people born in the United States are citizens and are thus entitled to “life, liberty, or property,” as well as equal protection under the law; and The Civil Rights Act of 1964 which prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin.

Those who use the Fourteenth Amendment and the Civil Rights Act to refute Affirmative Action argue that they are both race-neutral; the goal, they emphasize, is to protect all citizens, not just minorities. However, considering the time periods during which these documents were passed shifts

the perspective significantly.

For context, the Fourteenth Amendment was passed after the abolition of slavery to try to stop southern states from immediately reimplementing slavery under a different, more subtle name. The Civil Rights Act was passed nearly a century later in a response to rampant Jim Crow Laws spreading throughout southern states. Therefore, by calling the Fourteenth Amendment and the Civil Rights Act “race-neutral,” the claim becomes that the institution of American slavery and Jim Crow Laws were also raceneutral.

It doesn’t take a year of APUSH with Mr. Baran to realize that this claim is not correct.

On the other hand, the Fourteenth Amendment does not exclusively apply to injustices caused by the institution of American slavery. Indeed, the first court cases to implement this amendment were The Slaughter-House Cases of 1873, years after the Emancipation Proclamation. Louisiana passed a law that restricted New Orleans slaughterhouse operations solely to the Crescent City Live-stock Landing and Slaughter-House Company, leaving all other slaughterhouses out of work. Local butchers argued that this monopoly created involuntary servitude (a Thirteenth Amendment violation) and denied equal protection of the laws (a Fourteenth Amendment violation). The Louisiana court decision resulted in

these amendments actually having no purpose other than to ban states from “depriving [Black people] of equal rights” following the abolition of slavery, thus making the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments irrelevant in a modern setting.

It is commonly understood now that this court decision was—to put it nicely—really, really bad, but I feel like it is important to mention the 14th Amendment’s racial implications as well; I’m not trying to say that the Fourteenth Amendment should be viewed solely through the lens of Post-Civil War reparations, but rather that the context of slavery shows a lack of racial neutrality. Thus, it can be understood that the 14th Amendment and the Civil Rights Acts are not race-neutral, but they are meant to protect racial minorities well after the time of slavery. This shows that modern Affirmative Action arguments are not about protecting “all races,” but really just arguments of equity vs. equality with a racial basis.

150 years later, the SFFA v. Harvard case decided against Affirmative Action. Currently, Students for Fair Admissions is a non-profit organization run by Edward Blum, a 73-year-old white man from Michigan who went to the University of Texas at Austin. Blum earned some national fame in 2008 after backing Abigail Fisher in her lawsuit against the University of Texas at Austin, citing that she was rejected from UT Austin because she was Caucasian (conspicuously, not the fact that she had a

Art by Anderson Toole

Art by Anderson Toole

22 23

subpar SAT score and GPA, at least as measured by UT Austin’s admitted student body averages). With no proof that Fisher was rejected because of race, the Supreme Court voted in favor of Affirmative Action. Despite this very public loss, Blum continued to endorse SFFA, even creating a website devoted to people submitting their college rejection stories and airing their grievances.

As a senior, I understand that these grievances abound; when we feel wronged, we often want to be able to blame something other than ourselves. However, just because it feels nice to be able to blame something uncontrollable, rejection from college is not meant to open the doors to racial discrimination. The SFFA website opens these doors wide, fostering even more resentment for Affirmative Action.

The term “racial discrimination” is thrown around in nearly every other sentence in the SFFA v. Harvard case, but it’s never actually defined. However, it’s important to remember that race is a social structure that is intrinsically flawed and irrevocably ingrained in modern society, to the extent that everyone reading this has, at some point, made an immediate judgment about a person based on the color of their skin. Thus, using race as a metric is a flawed method created by flawed humans.

SFFA’s argument is mostly centered around the Fourteenth Amendment and the Civil Rights Act—claiming them to be race-neutral—in defense of White applicants, but they also bring up that Asian applicants are at a disadvantage under Affirmative Action. They have stated that racial categories such as “Asian” or “Hispanic” are arbitrary and not applicable to all Asian and Hispanic applicants. Though it is completely true that not all Asian and Hispanic cultures are encompassed under these terms, there is no evidence that such descriptors are something that can harm someone during a college admissions process. Nonetheless, these arguments quickly changed the case from white people versus Affirmative Action to white people and minorities—who were not actually physically represented by the SFFA team—versus Affirmative Action.

On June 29, 2023, the Supreme Court decided in a 6-3 vote that the consideration of race in college admissions did, in fact, violate the Fourteenth Amendment. The court also concluded that the SFFA was an organization founded and run under the principle of good faith: one that works toward equality for all students applying to college. Justices also made their decision in reference to Bakke v. California, stating the same argument held here, with Harvard and UNC both having “unconstitutionally” considered race in admissions. The final decision rendered that, by considering race, UNC and Harvard both failed to avoid racial “stereotyping” and failed to provide a

compelling, measurable reason for accepting certain students while denying others of equal skill sets.

There is a lot that is wrong with these decisions. First off, the Bakke v. California case was passed only because the quota system allowed California colleges to stop seeing people as people, but rather as vacancies to fill. Both Harvard and UNC have two rounds of admissions, the first eliminating all that don’t meet a minimum requirement of some kind, and the second based on a more holistic review of each student—this is when both race and legacy status come into question. These admissions systems do not adequately compare to the quota system in California state schools because everyone who is admitted is admitted because they are academically qualified, not because they meet a racial requirement.

Therefore, by calling the Fourteenth Amendment and the Civil Rights Act “race-neutral,” the claim becomes that the institution of American slavery and Jim Crow Laws were also race-neutral. It doesn’t take a year of APUSH with Mr. Baran to realize that this claim is not correct.

Furthermore, the argument that neither school had a good defense for wanting racial diversity on campus is simply false. The American Council on Education, a nonprofit organization, states that “diversity enriches the educational experience” for all students, allowing them to “learn from those whose experiences, beliefs, and perspectives are different from our own,” and thus enriching an academically curious environment. Finally, the court’s decision that Harvard and UNC failed to avoid racial stereotyping once again proves that this argument is not about race but is rather a debate of equity vs. equality.

When asked why someone is anti-Affirmative Action in college admissions, the most common response is that they do not feel comfortable with something uncontrollable being a factor in a decision that could change their future. However, it is not uncommon for people holding this opinion to also view legacy status as a viable factor in admissions. Such views directly contradict one another; like a person’s race, legacy status is not something someone can control.

Think about this: of the U.S. News & World Report’s top thirty schools, only ten were founded following the abolition of slavery, six of which are California

universities—with the first being founded in 1868. With California being a very new state at that point, this really means that of these cited 30 schools, only Johns Hopkins, University of Chicago, Rice, and Vanderbilt were founded following the abolition of slavery. This puts racial minorities at an immediate disadvantage with regard to legacy status; their ancestors having had no access to higher education, legacy status became an impossibility. As mentioned, legacy status at a university is not something that someone dictates—we cannot control the family we are born into, nor can we influence the choices made by our predecessors.

Furthermore, top universities often have a standard that people in a lower income bracket cannot meet. It’s not uncommon for a rejection letter to cite that a student was rejected not because they were unqualified academically, but because they couldn’t compete as well with others in the applicant pool. This competition lies in what applicants have accomplished outside of class like extracurriculars, summer programs, internships, all of which require not only a certain amount of time, but also money not available to all.

The US Department of Labor states that the average weekly salary of white men and women in America is $1,046.52; for African Americans, $791.02; for AsianPacific Islanders, $1,168.82; and for Latinx/Hispanics, $762.80. Furthermore, a 2019 survey found that 66 percent of those enrolled in a private high school were White, 9 percent were Black, 7 percent were Asian, and 12 percent were Hispanic. As a private high school, it is important for us—students at Porter-Gaud—to recognize all of the resources that we are provided on a regular basis that public schools do not always have: tutors on campus, upgraded technologies, and teacher availability, amongst other resources.

With their families typically earning a higher average wage and having more access to quality K-12 education, white high school students typically stand a better chance to be accepted into their colleges of choice. With this in mind, there is no way to conclusively know that abolishing affirmative action will actually make the college admissions process more equal. As it stands, there are no restrictions in place on writing about your race in any of the essays submitted to universities. As such, the many debates about affirmative action decisions have done very little to restrict the possibility of racial consideration in college admissions.

With this in mind, it’s important to talk about what college admissions will look like moving forward and how equitable its processes may be. If we base such predictions on what happened in California following Proposition 209,

the outlook isn’t great. The actual percentage of minority students enrolled in colleges and universities did not see any change; however, where they were being enrolled did. According to a Wall Street Journal case study, Proposition 209 resulted in almost a cascade effect: students who would have previously gone to a highly respected university would go to a university that was slightly less prestigious, and the person going to that slightly less prestigious university would now go to an even less prestigious university. This resulted in ethnic minorities in California being less likely to graduate and Black and Hispanic students more likely to earn significantly less in their later careers. The worst part is that these minorities were still in the pool of students qualified to go to these selective schools; however, lacking practical access to the extracurriculars that would have given them a competitive edge made their rejection almost guaranteed. To put it simply, abolishing Affirmative Action in California did not make admissions fairer; it just showed how unfair it was from the start.

As of right now—April of 2024—most people have received all of their college admissions decisions or are waiting on waitlist decisions. The end of the 2023-2024 college admissions season saw a statistical decrease

To put it simply, abolishing Affirmative Action in California did not make admissions fairer; it just showed how unfair it was from the start.

in enrollment for all races with a 13% drop for Native Americans, and an 8.8% drop from Black Americans while White American enrollment only dropped by 8.5%. This coupled with the fact that the number of college applicants in America increased by 9% this year, shows that, despite people saying that the SFFA v. Harvard case would have little effect on college admissions, we are likely on a downward decline in the admissions of racial minorities.

With 2024 as a reference, college admissions are only going to grow more competitive as those who are disadvantaged are going to fall more behind. This is not something that we should just accept, we need Affirmative Action in college admissions.

In the wise words of Nikole Hannah-Jones of The New York Times, “Race-based affirmative action has died. The fight for racial justice need not. It cannot.”

24 25

Crossword

Video Games

STEM

Literature

TV and Movies

Video Games

Across:

1- Controllable characters in 2000 video game

4- __Soft in America

6- (accr.) Video games for college applications

7- Person playing a video game

8- Kanjo SJ in GTA V

9- Game on a personal computer

12- ___con, twice in FNAF

13- (acronym) Extra content in a video game

Down:

1- How to confirm Arstotzkan identity in Papers, Please

2- HK416/7 in Call of Duty

3- “Suitable for persons 17 and older”

4- (accronym) Meme for “not-real” person

5- A couple seconds of a Twitch stream

10- Popular Portal 2 mod, Portal Stories: ___

11- Video Game Retailer: Video Games ___!

Across:

Literature

Across:

1- Ender’s ____

5- His name comes from “hold the door”

6- Type of cure developed in Maze Runner

7- Free Space (because this puzzle is hard): algtke

8- __st and __laxation

9- Fanfiction MFL stutter

11- Protagonist’s name in a novel with the style of Dante’s Inferno

12- Focus of The Ninth Hour

13- (abbr.) Popular Book-rating site

Down:

1- Sound the ____ by Joan He

2- Jesper Fahey’s mother in the Grishaverse

3- _______ jay, animal symbolic of Katniss Everdeen

4- Harry Potter’s hesitation, instead of “um”

5- Love interest that sparked Homer’s Odyssey

6- ____ Paulsen, author of Hatchet

10- (abbr.) Story told through pictures

STEM

1- Group of animals that include a red velvet and raspberry crown species

5- Negatively charged molecule

7- Quantity with direction and magnitude

9- Magnitude of acceleration due to gravity on Earth (1 sig fig)

11- Molecule that makes up starch and glycogen; C6H12O6

15- Devoutly opposed to NO4

16- There’s one for X and Y… and sometimes even Z

Down:

1- Type of computer file for sound

2- Organic chem ending; seen in fuels prop__ and but__ around the house

3- Silicon Carbide

4- Natural remedy for chronic pain, insomnia, anxiety and more, colloquially

6- First barrier in computer science (computer is ___ __)

8- An object at __ stays at __ until acted on by an outside force

10- The ___lithic Era ended around 2200 BCE

11- Codon corresponding to glutamic acid

12- e––– = x

13- Malady for the infrequent urinator

14- Type of isomer; opposite of “trans”

Across:

1- Sad movie with balloons

TV Shows/Movie

3- A tube put over a light to create a spotlight effect

7- Stranger

8- How you might describe Elliot’s father since his name is unknown

9- “That’s how Sue ___s it!”

10- Feel-good show about people who have found their own path, On the ____.

14- Lip ____ Battle, the dramatic end to an episode of RuPaul’s Drag Race.

Down:

1- The goal of the Tethered in Us was to _____ with Hands Across America.

2- Confused often, Derry Girls’ Erin Quinn regularly does this.

3- The World __ War, a famous 1973 WWII documentary.

4- ___’_ the Man

5- ___ Garra, a crime boss in Star Wars with a cantina at Disney’s Hollywood Studio.

6- (abbr.) Disease that made Miranda decide she wanted to work in pediatric surgery in Grey’s Anatomy.

11- __! A popular 2009 Bollywood romance film.

12- Name of the protagonist of The Avatar without the first or last letters.

13- The __U describes the world as in which all Marvel films exist in.

Key 26 27

E Pluribus Problem

What defines an American anymore?

Text and Art by Anderson Toole

The United States of America—this glorious bastion of western democracy, this land of the free and home of the brave—is a fragmented mess. This likely comes as a shock to absolutely no one reading this, especially if you’re a high school student who can hardly remember an election uncharacterized by charges of corruption, claims of election fraud, or an actual violent insurrection. But we are often told by those who can remember a time before, back in those good ol’ days, politics didn’t have quite the same explosive sensitivity. Strongly disagreeing with a friend or family member’s political stance could be touchy, but it was not a cause for disavowing them in the same way that it can be today.

This is not to say that everyone held hands and serenaded each other at joint red-blue (purple?) political rallies. But today’s polarization does stir up a considerable issue for what it means today to be American. In a nation where we are not united by one language, race, ethnicity, culture, religion, worldview, or really any other demographic, we used to have at least some agreement over politics. There was the sense that Americans—as different as we are—are all cut from the same cloth, so to speak. At least, the one party in power was usually relatively content, and the other reasonably patient for the next election cycle.

Now, however, nobody is either—Republicans say that the government is ruling with too strong a hand, threatening their rights and indoctrinating their kids; Democrats complain of infringements by conservative lawmakers on some issues, but protest that not enough is being done for others. To speak with someone who fully agrees with the current policies of the federal government these days—much less a whole party’s worth—is exceptionally rare. People may dislike a politician or party’s foreign policy but like their stance on social issues, or vice-versa; if they want to have any say at all in their government, they must prioritize the importance of these facets of the candidates and vote for someone they agree with mostly, but not completely.

So without enough common ground to unite us, what does it mean to be American? Everyone’s perceptions of American ideals seem to be different, many even overtly contradicting one another. Some are correlated with political leanings, others with religion, race, ethnicity, age, immigration status, or any number of other demographics. Broadly, though, there are only a few things that really stand out as intrinsic to the identity of the country itself.

The US, perhaps, has never been just in any real sense.

The US, perhaps, has never been just in any real sense.

Without enough common ground to unite us, what does it mean to be American?

First, liberty—the right to be, in whatever form it may manifest. Though it seems simple and relatively easy to uphold, the concept of liberty breaks down the moment it’s actually applied. Liberty could be an espousal of second amendment rights, but also the counterpoint that citizens have the right to walk freely in public spaces and be safe from gun violence. It must include the protection of personal rights, but personal rights for everyone, creating the paradox in which one’s freedoms become another’s restrictions.

This brings us to the second point: justice for all—the rights that we are individually entitled to. Justice has been compromised in the U.S. since it was founded, most obviously in the form of slavery and the legacy of racism and its institutions, sexism and gender inequality, xenophobia, and discrimination on the basis of race, religion, and national origin, homophobia, transphobia, and in countless other ways. The US, perhaps, has never been just in any real sense. But the pursuit of justice—and thereby the pursuit of happiness— has continuously pushed us towards increasingly progressive viewpoints on all of these issues. Though nothing is perfect, improvements have been sought out and implemented. As a result, the US has become a “mixing bowl” of all sorts of different demographics whose members (at least ideally) are entitled to justice under the law, whereas that may not be the case in other countries.

28 29

But it is exactly these—liberty and justice, and the other lofty, idealistic, only somewhat-enacted values—that may inspire some to assume a certain American moral superiority. We hardly even torment minorities, we think. Definitely less than Russia, China, or the Middle East. We’re so wonderful and the best country on the planet.

In reality, however, women are not paid nor treated equally; people of color are subject to aboveaverage poverty, mistreatment by law enforcement, and below-average education and employment opportunities; gun violence continues to escalate; and transgender people, who were on the verge of finally being accepted less than a decade ago, are once again steadily becoming excluded from public life. This is not to say that the United States is exceptionally cruel, but it certainly has room for improvement if it is to maintain its reputation and fulfill its founding fathers’ vision of “form[ing] a more perfect union.”

understandings of gender and sexuality (“Don’t Say Gay’’ bills). That is simply not the loving, inclusive community that early Christianity was supposed to be, no matter how modern bigots try to twist it.

Likewise, the USA has strayed far from its democratic ideals. Either party can claim that their policies are more constitutional or more in line with American values, but just as evidence can be found to support both sides of most ethical arguments in the Bible, Constitutional law can be interpreted by the judiciary to conflict with—and override—itself. There is no singular correct interpretation of American ideals, and that plurality has led to both Democrats and Republicans being devoutly convinced that their policies are more American than the other’s.

Puzzle Me This

maybe you can't not solve all of America's problems, but can you solve these? There’s a certain pattern inside each of these sequence puzzles. Find it to fill in the empty square.

At the heart of this issue is the fact that our nation does not actually have the democratic roots we like to imagine.

At the heart of this issue is the fact that our nation does not actually have the democratic roots we like to imagine. Neither people of color nor women could vote for nearly a century after the nation’s founding—the 15th amendment gave Black men the right to vote in 1870, and women’s suffrage followed with the ratification of the 19th amendment 50 years later. Even your average white men weren’t necessarily guaranteed voting rights at the nation’s founding—due to poll taxes and property requirements, poor folks and nonlandowners were often disenfranchised as well.