11 minute read

Chowder

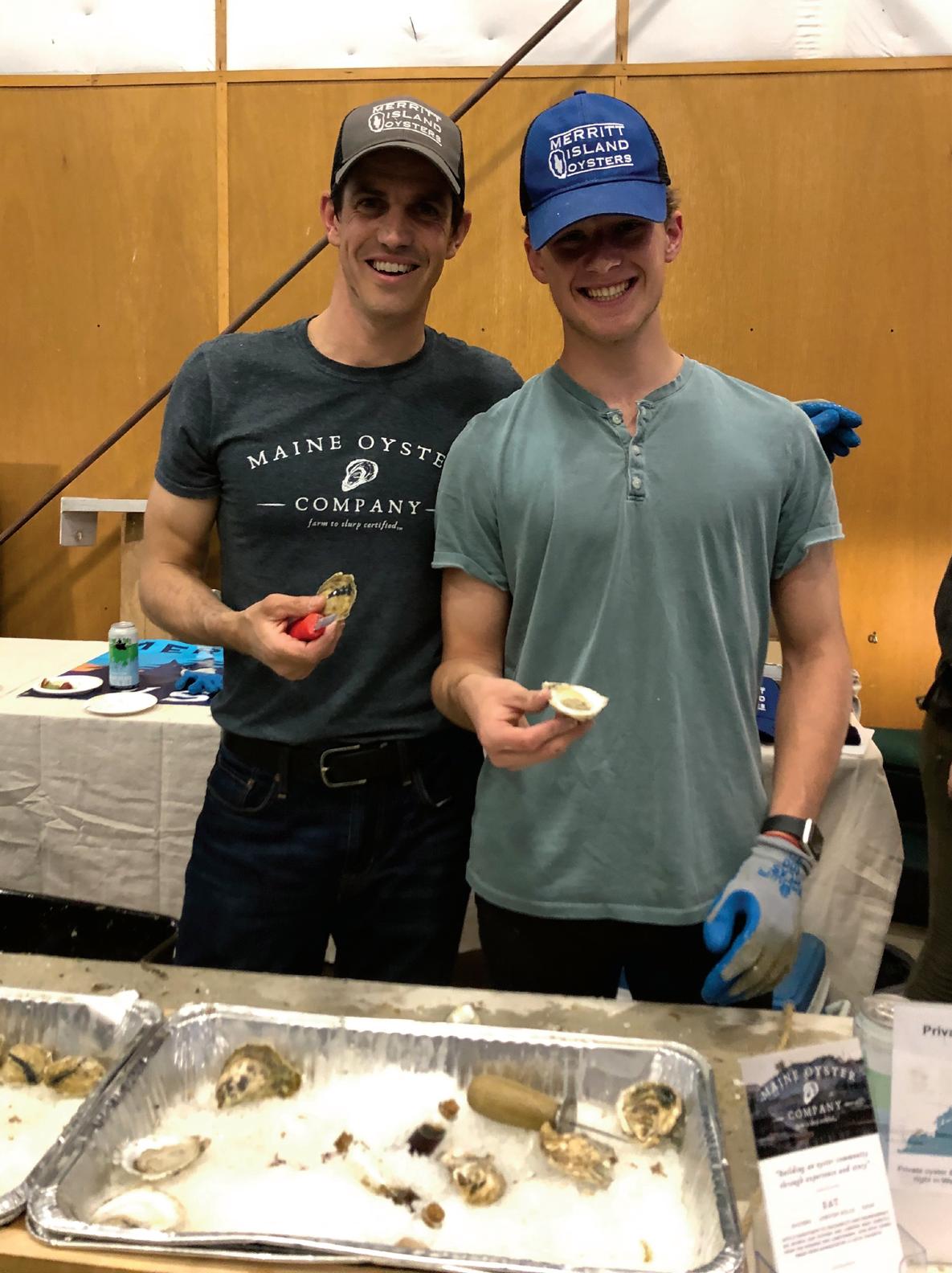

that platter of a dozen oysters you ordered with artisanal sauces and lemon slices on the side were almost certainly grown by someone since the time they were the size of the ngernail on your pinkie.

SEX ED

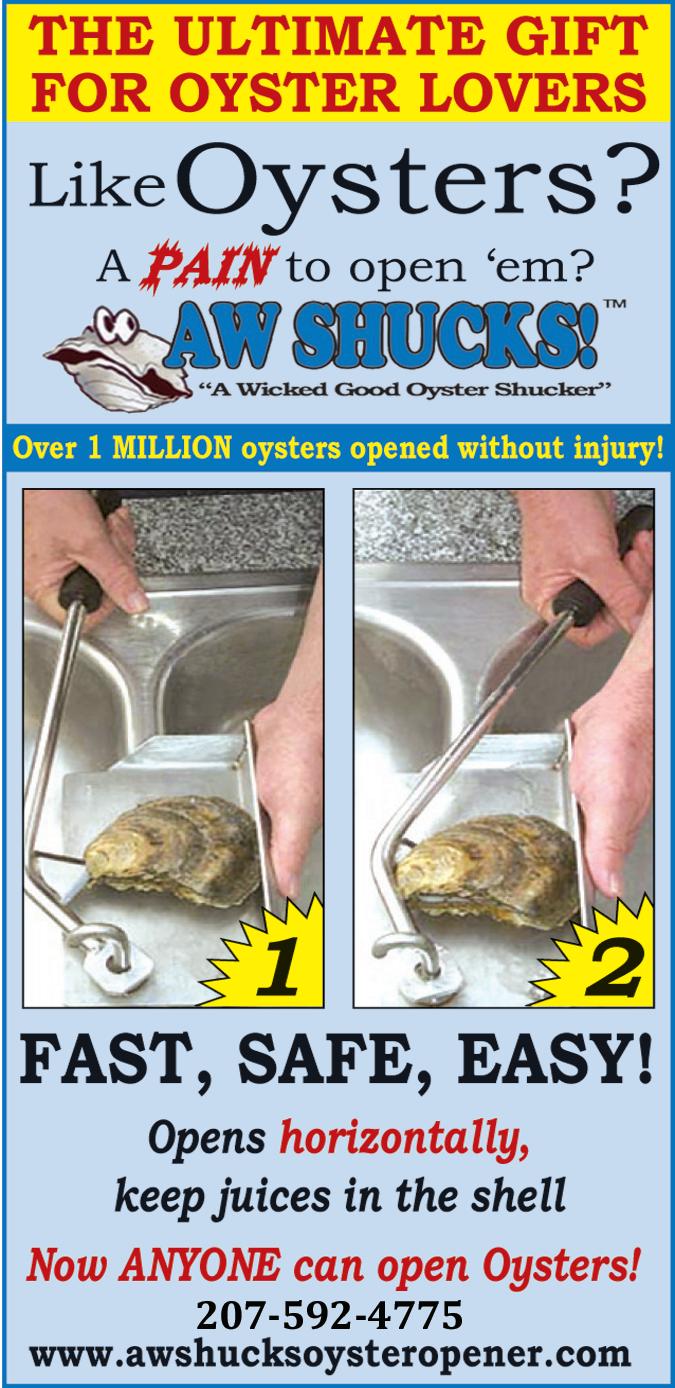

It’s hard to describe oyster farming without visual aids. e oysters, like I said, are grown from a very small size. Some farmers even reproduce the oysters themselves, producing oyster “seeds” which are then sold or grown. We purchase our baby oysters from many di erent hatcheries. Once we receive the seeds, they’re grown in plastic mesh bags roughly 20" x 40", with 4–14 mm holes. As “seeds,” thousands of oysters are placed into a bag, though just a small portion will survive. Four of these bags are then placed into a cage held up by two otation devices, allowing the oysters to sit below the water’s surface. e inconspicuous submerged cages and black otation pontoons respect the beauty of the Maine coastline, while brightly colored buoys warn boaters of the cages at the edges of the farm. Despite the minimal visual impact of our farm, we went out one morning to nd a few of our cages submerged—with bullet holes in their oats—courtesy of a nearby neighbor who was far from a fan of the farm “tainting” his view.

As the oysters grow, they’re put into

bags with larger holes to allow a greater water ow to bring them nutrients. Oysters are pretty low maintenance, and the ocean does most of the heavy li ing. Typical maintenance consists of scrubbing the cages and bags clean of algae, seaweeds, and, yes, their feces, to permit water ow. A deck brush and elbow grease usually gets the job done.

Once the oysters reach three inches (usually a er three years, measured by a small piece of a paint stirrer we cut as a guide), they’re ready for market. Ideal for eating just a few years into their life, many oysters can live up to twenty years.

Oysters’ beauty does not entail a sacri ce of strength or resilience. Rather, oysters’ seductiveness arises, in part, from their fortitude. e o en rough waters create friction which produces a deeper and smoother shell, making that plate of oysters look just a bit nicer for your social media posts.

Nor is the illustrious pearl a stranger to adversity. Pearls are formed when an irritant enters the body of the oyster, triggering a defense mechanism. e oyster releases a substance called nacre which coats the irritant, layer a er layer, until a pearl is formed. ough only

BEERCRAFT MAINE

LOCAL HADDOCK SEAFOOD STEAKS & BURGERS

CLASSIC OCKTAILS

Brunswick, ME Old Town, ME Rochester, NH

www.pepperslanding.com

one percent of oysters produce pearls, I dream of nding one.

HOMEGROWN

e oysters don’t travel far once they reach maturity. ey’re so delicious, they’re lucky to reach Portland’s restaurants at all. Initially our oysters journeyed further south to Boston, but soon increasing local demand allowed us to sell them just miles away from where they began their lives. You can now enjoy a taste of West Bath’s New Meadows River at the Maine Oyster Company or SoPo Seafood.

CRAFT

It’s easy to imagine Maine oyster farms as a mirror image of our state’s many cra breweries: every farm produces the same product, but each is distinct and appeals to di erent tastes, o en with a cult-like following. Briny, sweet, buttery. Hoppy, fruity, dry. Same idea. e water an oyster is grown in gives it a unique taste. e New Meadows River’s current and extreme Maine tides provide the oysters with constant water ow o ering them plentiful nutrients.

LANDLUBBER

Oystering was certainly not a summer job I’d ever imagined for myself. Like any kid growing up on the Maine coast, I spent the warmer months by the ocean. I always pictured myself scooping ice cream or mowing lawns once school let out for the year. So when early spring came around and I found myself being taught to zoom around in a boat on the rst day of the job just weeks a er leaving the DMV with my driver’s li-

Come Out of Your Shell

Your table is ready

cense, I was in uncharted waters. ough Maine waters in March are hardly a pleasant and forgiving place to learn to operate a boat, the next day I was out all alone on that 14-foot at-bottomed Carolina Ski . It’s now hard to believe I once spent my Maine summers folding khakis at Ralph Lauren.

CAPITALISTIC CRUSTACEANS

ere’s minimal marketing required to attract the consumers of oysters. So long as a highway exists between New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Maine during the summer, there’ll be a demand for them. ough many of our oysters are consumed by Vacationland visitors, some have ventured south to be sold in Boston’s Fenway-Kenmore neighborhood. ere’s something extra sexy about slurping down a Maine-raised oyster a er a Sox game. e roar of the Guinness-fueled crowds in the background as you eat your oysters at Eventide Fenway a block from the ballpark gate embodies the paradoxical wonderland New England has to o er.

Locally the wholesale price for oysters is pretty stable. For the most part, restaurants buy them for a buck apiece, though some larger restaurants buy them for seventy- ve cents to a dollar per oyster. Even though the going rate for a thousand one-millimeter oyster seeds is about $8, around eighty percent of the seeds die before they reach market size, so there’s definitely some risk involved.

HERE’S A HISTORY LESSON

I feel a watery connection with the oyster farmers before me, though not so much with their equipment. In A History of Oysters in Maine (1600s-1970s) Randy Lackovic of USM’s Darling Marine Center cites an 18th-century report to the King of France: “Oysters are very Plenty in Winter on the Coasts of Acadia, and the Manner of shing for them is something singular. ey make a Hole in the Ice, and they thrust in two Poles together in such a Manner, that they have the E ect of a Pair of Pincers, and they sel-

dom draw them up without an Oyster.”

Fast forward to the mid-20th century, and the Maine Department of Marine Resources is attempting to revitalize the depleted oyster population by depositing a new generation of mollusks sourced from Holland into the aquatic ecosystems of the Midcoast. But Maine waters proved too cold for European oysters, prompting University of Maine professor Herb Hidu to conduct a research project investigating their cultivation,

funded by the Sea Grant in 1972. Initial success breeding these European oysters to be able to withstand Maine oceanic environments was curtailed by an invasive parasite. A er this failed attempt, Hidu and a new wave of graduate students (many of whom went on to start their own aquaculture operations) turned their attention to the Crassostrea virginica or Eastern oyster, native to the Atlantic, in the 1990s. Success! Maine’s oyster industry grew by nearly 50 percent from 2020 to 2021, generating over $10M in a single year.

TRADE SECRETS

As you embark on your oyster odyssey, here are some facts of edutainment that will help you impress even your most pretentious oyster-eating friends. For starters, oyster farmers in the northeast sink their oyster cages to the ocean oor during the winter months to allow the oysters to go dormant while the water’s below freezing. Next, oysters aren’t actually an aphrodisiac, so stick with the chocolate and strawberries on your next date night. While it’s commonly thought that you shouldn’t eat raw oysters in months that don’t contain an “R,” you should rather avoid oysters that have been harvested during a “red tide” algae bloom. One oyster can lter y gallons of water per day, which means eleven million oysters can lter 550,000,000 gallons every day. Oysters are so cool New Yorkers are trying to grow a billion of them across the ve boroughs.

NOT-SO-OLD MAN AND THE SEA

As I begin to start thinking about trading my college classroom for an o ce and my dorm room for an apartment, oystering will, I hope, remain a perennial part of my life. I long to live within a stone’s throw of the Atlantic Ocean for the rest of my days, and dream that someday I too can employ a naive, underquali ed sixteen-year-old to run my oyster farm as I attempt to conquer the real world. n

The Rises Curtain

Another Op’nin’, Another Show

BY GWEN THOMPSON

The show must go on, and one way or another it did. We’ve emerged from the pandemic with a new appreciation for virtual performances (“Love the One You're With,” right?) and the hope that live and on-demand streaming will continue to make theater more accessible to those unable to attend in person. Yet there’s no business like show business, and nothing like live theater. If that lump in your throat when the house lights go down melts into tears of joy to be back in the audience at last, you’re not alone.

Here’s a sampling of what’s on the boards in Maine this season—see our eater Listings on p. 66 for much more!

ELEMENTARY, MY DEAR

Whether you favor Basil Rathbone’s interpretation or Robert Downey Jr.’s, it’s liberating to know Sir Arthur Conan Doyle himself gave co-author and leading man William Gillette free rein with the very rst Sherlock Holmes play. In his 1923 autobiography Memories and Adventures, Conan Doyle recalls telling Gillette: “You may marry or murder or do what you like with him.” Track down Sherlock Holmes: e Final Adventure—Steven Dietz’s Edgar-winning adaptation of the 1899 play—at Portland Stage Oct. 26–Nov. 13.

WHO WILL BUY?

e Pre-Raphaelites weren’t all aming red hair and pretty wallpaper patterns. You know something’s not quite right when dozens of fruits from di erent climes are “All ripe together/In summer weather...Who knows upon what soil they fed/ eir hungry thirsty roots?” Join unsuspecting sisters Laura and Lizzie on an enchanting musical journey to the Goblin Market, adapted from Christina Rossetti’s sweetly creepy poem by Polly Pen and Peggy Harmon, at Denmark Arts Center Oct. 28–30.

CAROUSEL UNPLUGGED

You know you’re a Mainer if you free-associate Rodgers & Hammerstein with Boothbay Harbor rather than Oklahoma or the South Paci c. Savor Carousel’s stunning score undistorted by ampli cation in Good eater’s intimate production with twin-piano accompaniment at St. Lawrence Arts Nov. 9–Dec. 4.

OLD FAMILY RECIPES

Nope, it’s not the latest artisanal cocktail. If you missed the virtual reading of Sweet Goats and Blueberry Señoritas by Richard Blanco (2013 inaugural poet for President Barack Obama) and Vanessa Garcia (International Latino Book Award winner) at the Little Festival of the Unexpected last spring, you can still sink your teeth into this tale of a Cuban-American baker torn between Maine and Miami as a mainstage production at Portland Stage Jan. 25–Feb. 12, 2023.

CALL ME INEVITABLE

You could probably draw a Venn diagram to illustrate the overlapping spheres of in uence of lobstermen, marine scientists, tourists, islanders, and property developers, but writing a culture-clash lobstering musical as composer and ImprovAcadia co-founder Larrance Fingerhut and Second City playwright Andy Eninger have done sounds like a lot more fun. Catch the world premiere of Trapped the Musical at Penobscot eatre in Bangor Feb. 9–Mar. 5.

COLD WAR

Two artistic egos con ned at close quarters...what could possibly go wrong? Although Maine artist Jamie Wyeth o en found it easier to paint ballet superstar Rudolf Nureyev without him in the room, Nureyev’s Eyes by David Rush reveals how they eventually achieved détente. Step inside the artist’s studio in this Good eater production at St. Lawrence Arts Feb. 22–Mar. 12, 2023.

MARGINALIA

Part of the heartbreak of Anne Frank’s diary is its extreme circumscription mirroring that of her life. And en ey Came for Me: Remembering the World of Anne Frank by James Still combines videotaped interviews with Anne’s rst boyfriend, Ed Silverberg, and her neighbor Eva Schloss (whose family was also betrayed, arrested, and sent to concentration camps) with live actors in scenes from their lives during World War II. Venture beyond the pages at the Footlights eatre in Falmouth Mar. 16–Apr. 8, 2023.

ASK JEEVES

Lacking an omniscient butler on standby, I keep P. G. Wodehouse books on hand as mental emergency rations, because when nothing makes sense—as it hasn’t for several years now—the only antidote is Perfect Nonsense of the kind only Bertie Wooster can stammer out. Let loose some long-overdue laughter with the Goodale Brothers’ Olivier Award-winner for Best New Comedy at the Public eatre in Lewiston Apr. 21–30, 2023. n