3 minute read

Th e Italian Renaissance by Reverend Dom Paschal Scotti O.S.B

The Italian Renaissance

By Reverend Dom Paschal Scotti O.S.B.

“You know what the fellow said – in Italy for 30 years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder, and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland they had brotherly love - they had 500 years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? Th e cuckoo clock.” -Th e Th ird Man 1949

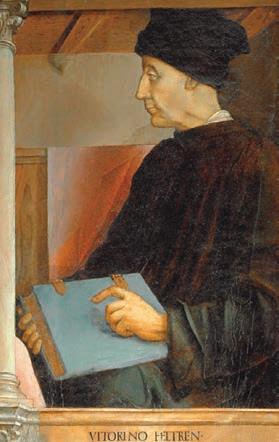

While this quotation from that classic of fi lm noir overplays the violence of the Italian Renaissance (and the pacifi sm of the Swiss), it does show the signifi cance and fascination that the Italian Renaissance has played in the West. For many people (and far too many texts), the view of the Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt (18181897) in his Th e Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (1860) that it was the birth of modernity, secularity and individualism, still holds true. When I went to Columbia University in 1979, the home of the great Renaissance scholars Paul Oskar Kristeller (1905 -1999) and Eugene Rice (1924 -2008), I learned that Burckhardt was wrong, profoundly wrong. It is for that reason that I am very pleased – for the fi rst time – to introduce a class on the Italian Renaissance at Portsmouth Abbey School. Th e Italian Renaissance brought many things to the West, including the modern boarding school, which, to a great extent was inspired by the humanist educator Vittorino da Feltre (1378 -1446).

His La Giocosa (“the pleasant house”) at the court of the Gonzaga lords in Mantua (1423 -1446) was known for its training of the whole person (mind and body), for its fundamentally humanistic and Christian worldview, for its profound kindness and respect for the individual, and for its attentiveness and mentorship. To a great extent its success was all due to Vittorino who saw himself as a father to these young men and approached teaching as a sacred task and vocation. Like another great Italian educator Don Bosco (18151888), he believed that involvement and kindness went a long way in the molding of his students into Christian gentlemen, models of classical learning and Christian virtue. Two of the most famous products of his school were Frederico da Montefeltro (1422-1482), the erudite scholar, superb soldier and diligent prince of Urbino (which Castiglione made famous in his Book of the Courtier) the greatest condottiere (mercenary captain) of the Italian Renaissance, and Lorenzo Valla (1407-1457) one of the most signifi cant of its humanists.

While we will certainly study education (both secondary and university) and humanism (the revival of classical literature, Greek and Latin), we will also study political and social history, economics and war, religion, art and literature. Between 1300 and 1650 Italy was the place to be, the center of culture and learning, the center of most things in Europe, the focus of its attention. By its end the students will not only know why Burckhardt was wrong, but why the Italian Renaissance was still a special period in history, in its highs and lows, with its Borgias (an infamous family which included Pope Alexander VI) as well as its Borromeo (the holy reforming bishop of Milan in the 16th century). It would be an appropriate companion to my book on Galileo (Galileo Revisited) and an interesting ride.

Reverend Dom Paschal Scotti O.S.B. graduated from Columbia University in 1983 with a degree in history and joined the monastery that summer. He also holds a M.Div. from the Dominican House of Studies in Washington, D.C., and a J.C.L. degree in canon law from the Catholic University of America. In 2006, the Catholic University of America Press published his study of the English Catholic man of letters Wilfrid Ward, Out of Due Time: Wilfrid Ward and the Dublin Review. He has also published in the Catholic Historical Review, the Downside Review, the revised New Catholic Encyclopedia (and its online version), and the Encyclopedia of Catholic Social Th ought. His book about Galileo, Galileo Revisited: Th e Galileo Aff air in Context, was published by Ignatius Press in the fall of 2017. Fr. Paschal has taught in the Christian Doctrine Department (where he was chairman for many years) and currently continues to teach in the History Department. He was an assistant houseparent for fi ve years in St. Benet’s and for one year in St. Leonard’s, and he continues to say Mass in the residential Houses.

Portrait of Vittorino da Feltre, Pedro Berruguete and Giusto di Gand, c.1474.