9 minute read

FROM REDLINING TO BLUELINING: The NYPD’s Policy of Stop and Frisk

by Jesse Such

City and Regional Planning Thesis. Spring 2018

Advertisement

On Halloween in 1963 three men—John W. Terry, Richard D. Chilton, and Carl Katz—were standing near the corner of Euclid Avenue near East 14th Street in downtown Cleveland, Ohio. Terry and Chilton were walking back and forth along this block until they were joined by Katz moments later. Terry, Chilton, and Katz were approached by Officer McFadden who, after watching them for several minutes, decided they were behaving suspiciously, and went with his gut to stop, question, and frisk them. Officer McFadden was a veteran of the Cleveland Division of Police, and his specialty was identifying pickpockets. What, if any, resemblance did Terry, Chilton, and Katz have to being pickpockets?

Photo taken during the aftermath of the Michael Brown killing by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri

Source: The New York Times

McFadden’s assumption was spot on; as he frisked the three men he found two guns and realized through questioning them that these men were casing a jewelry store with the intent of robbing it. And five years later, on June 10, 1968, the United States Supreme Court ruled that Officer McFadden had the right to stop, question, and frisk these three men before a crime had been committed.

The implications of this Supreme Court case, Terry v. Ohio, has reverberated across inner cities in the United States for almost half a century, including in New York City, where the New York Police Department (NYPD) has come under the spotlight for its aggressive policing tactics. Over the nearly two decades since the NYPD first began tracking Stop and Frisks, there have been so many people stopped and frisked that there are hundreds of thousands of points of data per year and over several million points of data during the last decade. These data points also include how many Stop and Frisks led to arrests. “An analysis by the NYCLU revealed that innocent New Yorkers have been subjected to police stops and street interrogations more than 5 million times since 2002 and that black and Latino communities continue to be the overwhelming target of these tactics. Nearly 9 out of 10 stopped-and frisked New Yorkers have been completely innocent.”

What bound these two eras of policing together in New York City is a lesser-known police officer who went by the name Jack Maple. Maple reinvented the way crimes were documented by mapping where crimes took place, and then by flooding the area with a high presence of police officers. It was Maple, not Police Commissioner William Bratton who gets most of the credit, who was responsible for the development of CompStat –a computerized data center to track where, when, and what crimes were occurring. David Remnick of The New Yorker profiled Jack Maple in 1997.

Jack Maple

Source: The New York Times

It was Maple who helped develop the software program that allowed the NYPD to “map” where high crime areas were. The NYPD then attempted to curb crime in these neighborhoods by saturating the areas with large police presences that were also heavily militarized. Maple called his maps “charts of the future.”

In 1994 Maple’s maps became known as CompStat, or Complaint Statistics and his methodology was implemented throughout the NYPD. The maps pinpointed where crimes were occurring. The NYPD then decided how to rapidly and aggressively respond to these crime areas, akin to what later was called shock and awe (in connection to the War in Iraq). Maple believed that conventional policing was “dysfunctional” and preferred a more “military” type of response to crime.

This “military” type of response to crime by Jack Maple actually began at the national level a decade earlier as Michele Alexander points out in “The New Jim Crow: the transformation from ‘community policing’ to ‘military policing,’” began in 1981, when President Reagan persuaded Congress to pass the Military Cooperation with Law Enforcement Act, which encouraged the military to give local, state, and federal police access to military bases, intelligence, research, weaponry, and other equipment for drug interdiction, and subsequently “stop-and-frisk programs were set loose on the streets.”

The research here presents data that was analyzed between the years 2006 to 2016. The data that was analyzed was obtained from the NYPD and their records on Stop, Question, and Frisk. During this time criminal justice reformers had already filed multiple lawsuits against the NYPD for the discriminatory practice of Stop and Frisk, and in 2013 Judge Shira Schiendlin ruled that the manner in which the NYPD practiced Stop and Frisk was unconstitutional based on racial profiling. The most well known case was Floyd v. City of New York. But there were two other cases more pertinent to urban planners: Ligon v. City of New York and Davis v. City of New York. These cases focused on private and public housing. Consider for a moment the testimony of the plaintiffs from all three cases:

- “Violated”

- “Disrespected”

- “Angry”

- “Defenseless”

- A cop calling you “a fucking animal”

- “It’s like when you’re a kid, when someone is bothering you or someone is like threatening you, you run to your parents for protection, and when you’re an adult, you’re supposed to run to the police. But who are you supposed to run to when like the police are harassing you or like threatening you…, who are you supposed to run to then?”

- A police officer “told us that we can’t stand in front of our building, so when they come back we would need to be gone.”

- “Helpless”

- “Embarrassed”

- “Worried”

The stop made him feel the officers were biased “because I am being stopped all the time just because of the kind of neighborhood that I live in.”

From an urban planning standpoint, there is also something much more insidious than just a heavy police presence. There is also an architectural police presence looming even when the police are not there that make certain communities in New York City feel as if you are in a crime zone even when no crimes are being committed. Mike Davis states that there is an “architectural policing of social boundaries,” and that what is taking place today is the “militarization of city life.” He delves deeper by indicating that this is “only visible at the street level, to merge urban design, architecture and the police apparatus into a single, comprehensive security effort. The social perception of threat becomes a function of the security mobilization itself, not crime rates. White middle-class imagination, absent from any firsthand knowledge of inner-city conditions, magnifies the perceived threat through a demonological lens.”

If crime rates are not the cause of a heavy police presence as Davis astutely points out, what is? The Stop and Frisk data that was analyzed from 2006 to 2016 obviously points to racial discrimination, but also a new form of discrimination that I coin as “Bluelining.” In a sense, New York City went from Redlining in the 19th Century to Bluelining in the 20th Century. The term Bluelining refers to a heavy police presence that essentially cordons off one neighborhood from the next, making residents feel as if they cannot come and go as they please, and that they have no right to the City.

Examples of Architectural Policing and the Militarization of City Life Leading to Blue-lining: Cranes for Surveillance and Generator Lights for Sidewalks

Photos: Jesse Such

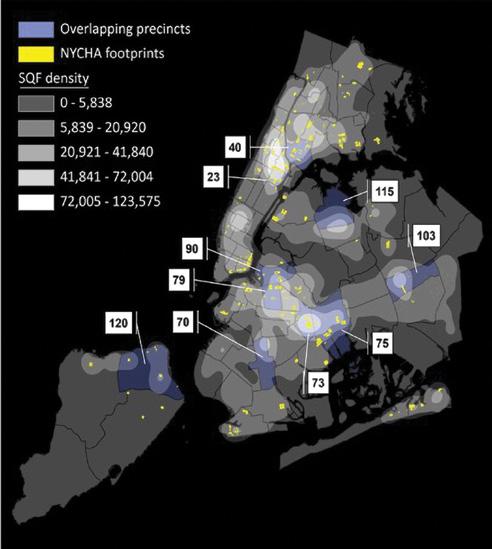

There are 77 police precincts located throughout New York City. Using a variety of variables I was able to identify 10 out of the 77 police precincts that are being bluelined by the NYPD. In order to identify these 10 precincts that are being bluelined, I analyzed the top quintiles of the total Stop and Frisk Rates between the years 2006 to 2016; the discrepancies between Stop and Frisk and Crime Rates; and the discrepancy between Stop and Frisk and Arrest Rates. Figure 3 identifies the 10 precincts that are being bluelined in New York City, as well as the NYCHA footprint that is being overly targeted by the NYPD.

In summary, criminal justice reformers, alongside urban planners, must ask themselves how to prepare for not only racial discrimination among police departments, but also about geographical discrimination. How do police officers attitudes change depending on what borough or neighborhood they are working in? Do residents fare well if they are living in middle or upper class neighborhoods versus poorer neighborhoods? What the map in Figure 3 shows us is not only police discrimination in less wealthier neighborhoods, but also racial discrimination and discrimination based on public housing. If these three indicators demonstrate how people are policed, much more reform is needed.

It is possible that the end of an era in Stop and Frisk has come to pass in New York City; that we will no longer see the extreme numbers of Stop and Frisks we witnessed during Mayor Bloomberg’s extenuated time in office. As soon as Bloomberg left office, Stop and Frisk rates dropped by 175 percent from its peak year in 2011. Yet, the violence that is perpetrated by police officers in communities of color predates Mayor Bloomberg and can logically be expected to persist or evolve without a concerted effort to assure otherwise.

Stop and Frisk in New York City is a policy that explicitly blue-lines communities—where the NYPD creates random perimeters in neighborhoods within certain precincts keeping people in and out—by concentrating police officers in the most vulnerable, isolated, and disconnected parts of the City to intimidate primarily the poor and public housing residents. In wealthier areas of the City, the same policy is designed to keep people out. This policy, over the course of several decades, has turned into residential segregation through police enforcement. This study and thesis recommends that urban planning principles on how to remove the call for Stop and Frisk, and in some respects reform the NYPD, be presented to lawyers working towards these remedies. The testimony from the Plaintiffs in the three court cases is too powerful to ignore. “I can’t breathe,” is an expression where communities of color and the streets and sidewalks that they walk on are being asphyxiated by the NYPD’s policy and tactics that are being abused through their use of Stop and Frisk.

Describing neighborhoods as “occupied territories” with roving checkpoints, where the atmosphere has such police hostility you feel as though you are being discriminated against because of where you live, points to a rogue police force where the only rhyme or reason in policing strategies in New York City is to persecute communities of color.

Overlapping Top Quantities of Total Stops, Questions, and Frisks

Source: NYC Police Department and NYC Housing Authority

More radically, perhaps the results of the landmark court case, Floyd v. City of New York, to reform the NYPD, should not be compared to Terry v. Ohio, as it has been for so long. Maybe the Floyd case should be compared to Plessy v. Ferguson or Brown v. Education, where individuals stood up for their human rights to demand an end to segregation. And maybe the individuals that we reviewed in the three court cases should be compared to other individuals: Rosa Parks, Jane Jacobs, and Eric Garner. Activists, advocates, and martyrs for police reform. People who fought to end racism and segregation.

References

1_New York Civil Liberties Union. “Stop and Frisk Data.” Accessed December 6, 2017. https://www.nyclu. org/en/stop-and-frisk-data.

2_Remnick, David. 2014. “ The Crime Buster.” The New Yorker, February 16, 1997 Issue. https://www.newyorker.com/ magazine/1997/02/24/the-crime-buster.

3_Alexander, Michelle. 2010. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. The New Press, New York.

4_Davis, Mike. 2006. City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles. Verso.