9 minute read

Behind the wire

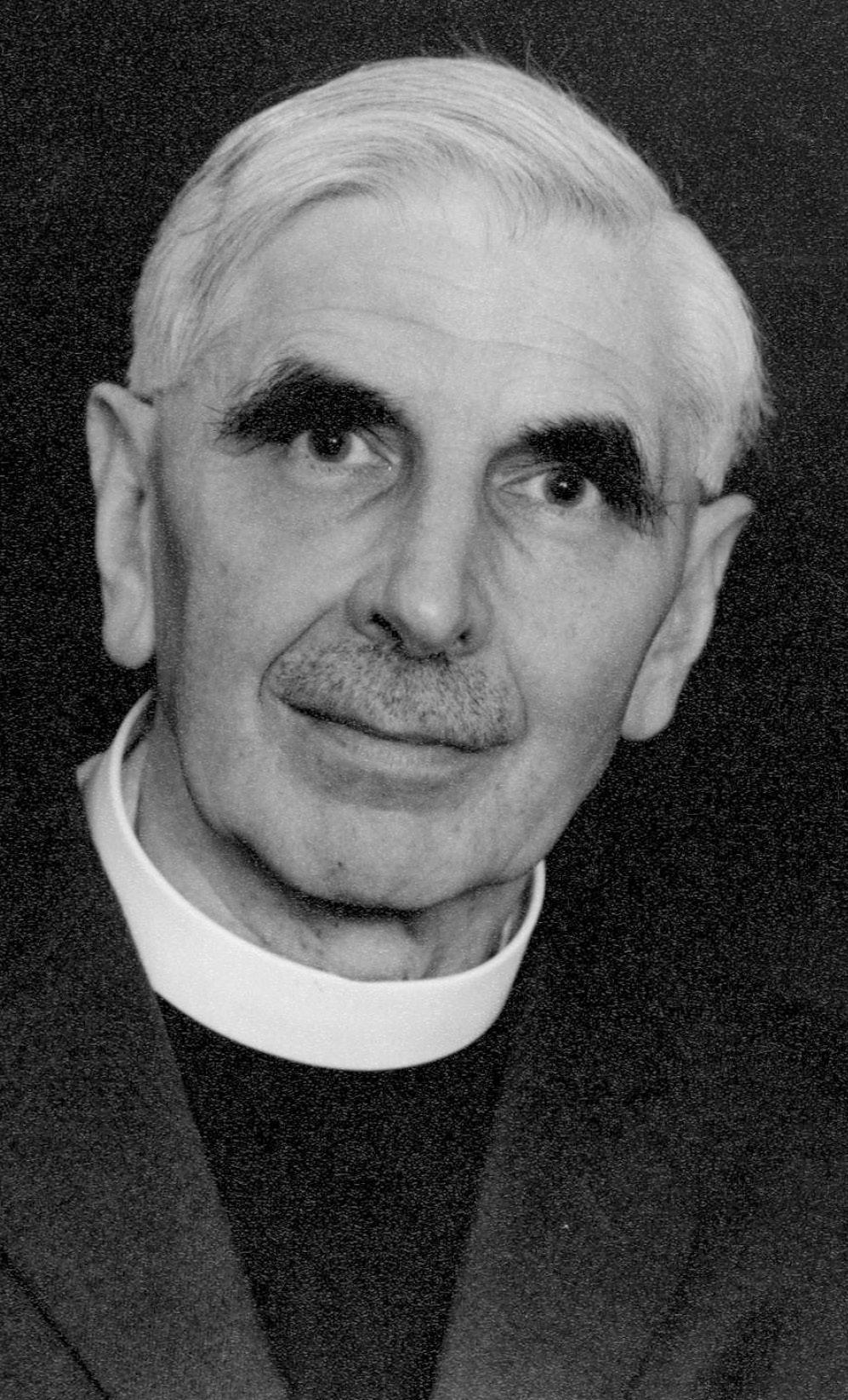

As we commemorate Remembrance this month, Dr Ian McNie explores the life of Charles E.B. Cranfield, a preacher, pastor, padre, pioneer and professor who served as an army chaplain during the Second World War.

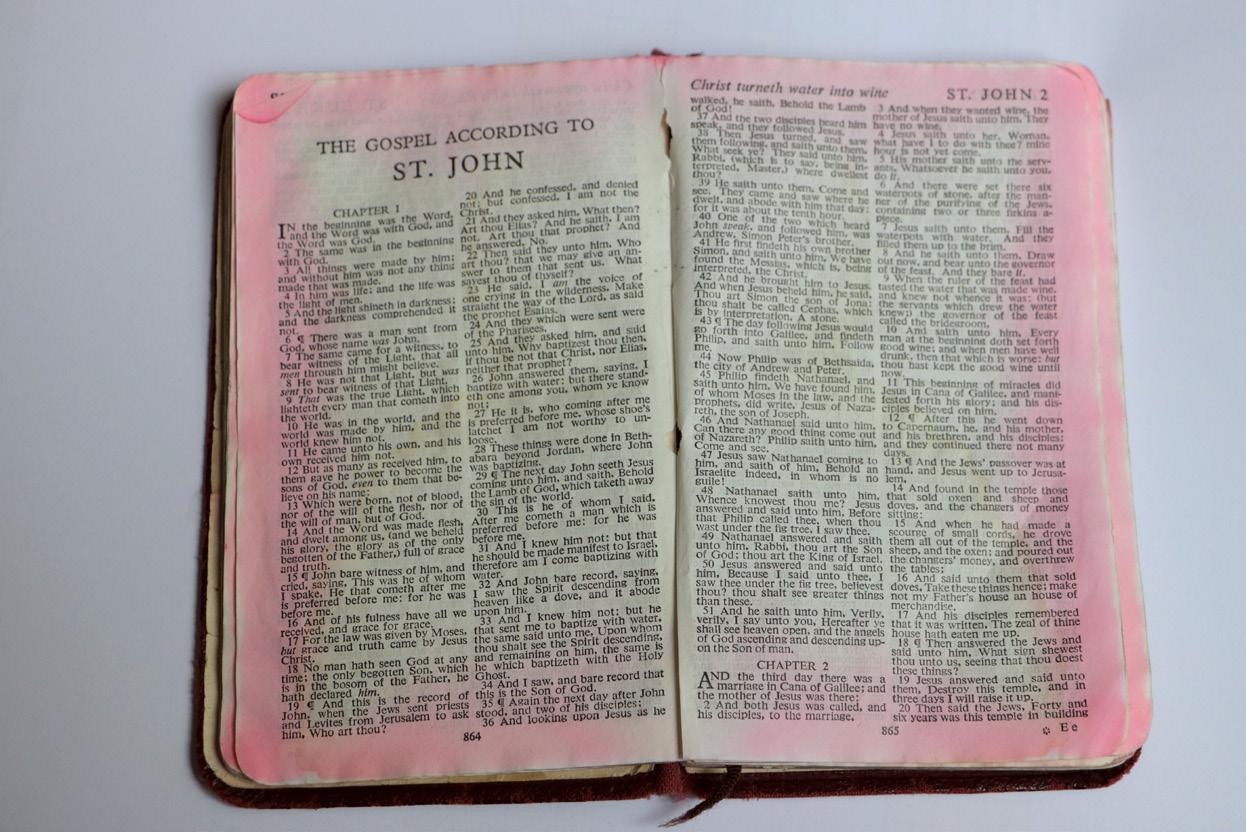

Many of those who served in the World Wars spoke little of their experiences on their return. My father David often modelled this reality, but on occasions did share his experience of landing on Gold Beach in Normandy on ‘D-Day’ as a serving member of the 51st Highland Battalion. As the landing craft neared the beach, its commander instructed him to list the names of all the 74 soldiers on board. Opening the fly leaf of a testament, Jesus Among Men, given to the troops by the Chaplain General, he recorded the names of all present.

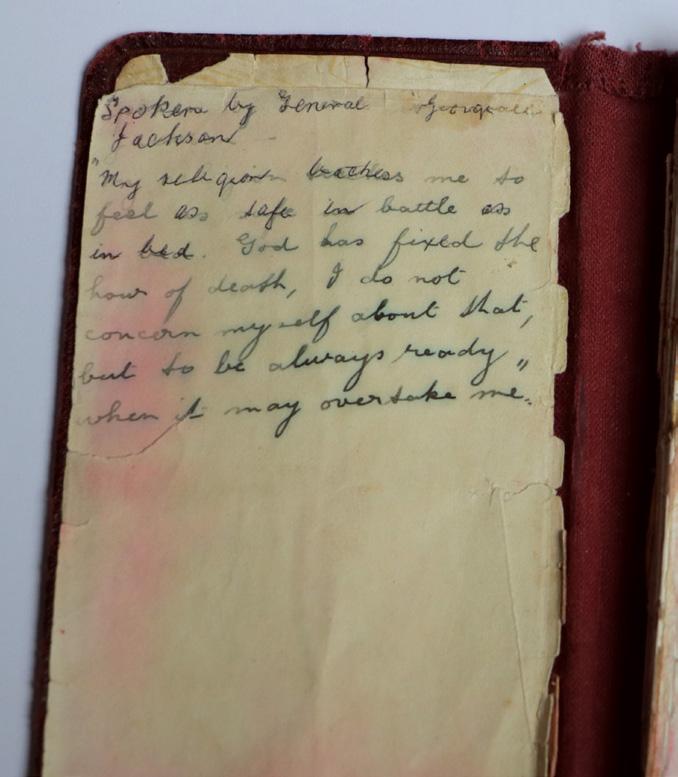

On disembarking, and arriving at the pre-determined rendezvous point, he was ordered to call the roll, by ticking the names of those present. The list reveals that not everyone made it. Some drowned as their heavy backpacks pulled them under the water, while others fell foul of enemy gunfire. Also in his pocket, my father had a second New Testament, which was stained by the waters of the Normandy waves. In it, he had written a quote from American Civil War General ‘Stonewall’ Jackson: “My religion teaches me to feel as safe in battle as in bed. God has fixed the hour of death, I do not concern myself about that, but to be always ready when it may overtake me.” While the collective experience of many soldiers paints a graphic picture of the horrors of war, there are also those whose stories show the other side of those dark and difficult days.

As a representative of PCI to the Waldensian Assembly in Italy, I met a Church of Scotland minister, Mary Cranfield, a regular attendee who ably guided first-time representatives regarding the procedures and nuances of our hosts. Recognising the name Cranfield, I was prompted to ask if she was related to Charles E.B. Cranfield, the internationally renowned New Testament scholar. He was Mary’s father.

Within our own denomination, and worldwide, generations of theological students have studied his books on the Greek texts of Mark and Romans. Through conversations with his daughter, it was obvious that he was not only a theological professor, but also a preacher, pastor, padre and pioneer, with a wealth of experience that far surpassed the realms of academia.

Long before his appointment as Professor of New Testament at Durham University, his legacy by the end of the Second World War had contributed significantly to the command of Jesus Christ, to “go into all the world”, and also, to Christ’s promise: “I will build my church”.

…he offered his services to visit German prisoners, providing ministry for them, and gaining fluency in the German language.

Cranfield, as a probationer for the Methodist ministry, was too young for ordination, and volunteered in 1942 as an army chaplain. After six months’ service in the 3rd Battalion of the Welsh Guards, he was called up to join the S.S. Strathallan, a passenger vessel conscripted to transport over 4000 troops, engaged in a special mission, code named, ‘Operation Torch’. Torpedoed by a German U-Boat, virtually all the personnel were rescued by accompanying ships in the convoy, before arriving in Oran, North Africa.

Cranfield spent the next 18 months providing ministry in two hospitals on the coast of Algeria. In 1943 he was asked to provide worship services for the British staff working in a prisoner of war camp, and in so doing, he offered his services to visit German prisoners, providing ministry for them, and gaining fluency in the German language. He forged friendships with high-ranking German personnel, one being General Hans Cramer, who after his return to Germany, became involved in the military leaders’ ‘20 July’ plot against Hitler. This pattern of ministry to POWs was a model he replicated on future occasions.

In June 1944, the hospital was moved to Italy, and a few months later Cranfield requested to be posted into a combatant unit, enabling him to better understand those who were on the front line. This posting with the Royal Tank Regiment only lasted for a short period because of the unexpected cessation of hostilities on 29 April 1945.…he persuaded the authorities to prioritise the return of some pastors to Germany.

…he persuaded the authorities to prioritise the return of some pastors to Germany.

At this point, the Deputy Chaplain General, acting on his own initiative, without War Office consent, appointed Cranfield to look after German pastors who were not exempt from frontline military service, and also engage in pastoral work among Protestants in the surrendered German army. These pastors were traumatised, vulnerable, depressed, and guilt-ridden as a result of their past actions and needed both emotional and spiritual support. Cranfield and others identified this as an important ministry, and spent much time with these prisoners. Having received a level of spiritual and emotional healing, these pastors in turn exercised a similarly effective ministry, assisting other prisoners of war, whose mental health was fragile and self-worth at rock bottom.

In this new field of work, one of his first duties was to visit Pastor Martin Niemöller in Naples, where he had been brought on his release from a German concentration camp. Niemöller, a former U-Boat Commander, initially an ardent supporter of the Nazi regime, was now a member of the Confessing Church, having recognised the incompatibility of Christianity and Nazi philosophy. He became a most outspoken critic and was imprisoned by a direct order from Hitler, serving eight years before his release.

Niemöller played a major role in rebuilding the evangelical church in Germany. Cranfield met with him regularly, encouraging and assisting him. Niemöller stressed the necessity for the repatriation of German pastors, as early as possible, to give leadership at home, and counter the influence of the Nazis in the German church. In response, while in Italy, Cranfield spent much time arranging the repatriation of pastors not needed in the POW camps, recognising the huge shortage of them in Germany. He, like Niemöller, realised that the Confessing Church, over and against the politicised German church, needed to be the voice of gospel proclamation in Germany. To meet with and implement the ideas of Niemöller to strengthen the Confessing Church, was an act of extreme courage on the part of Cranfield.

When Cranfield returned to England, his reputation had preceded him, and he was appointed, unofficially with the support of the Chaplain General and of the War Office, as a staff chaplain, and given access to those working in the political intelligence department. Visiting London POW camps, where there were no German Protestant pastors, he arranged for pastors to be transferred from other camps.

Remembering conversations with Niemöller, he persuaded the authorities to prioritise the return of some pastors to Germany. For pastors remaining in the UK, with the assistance of the YMCA, the British Council of Churches and the British and Foreign Bible Society, Cranfield organised resources for the spiritual, pastoral and emotional upbuilding of these weary, disillusioned, discouraged, traumatised and demoralised pastors.

Cranfield’s mind constantly focused on how he could help pastors and individual prisoners of war, to understand that the church cared, and he wrote to many clergy in England and Wales, encouraging them to visit POW camps within their locality. Many of the POWs suffered with immense pain and anxiety, recognising their side had lost, and hearing news of hunger and hardship back in Germany. He believed that a visit from a British pastor had a value and importance, out of all proportion to the little effort and trouble involved. At one point he drafted a letter and asked church leaders to sign it as a token of their support for the German pastors who were appointed chaplains in the camps. Two Archbishops, the Moderators of the Church of Scotland and the Free Church Federal Council responded positively to this request.

The church leader who responded most positively to Cranfield was his close friend and ally, George Bell. Collectively, his positions, contacts and interests were invaluable. As Bishop of Chichester and member of the House of Lords, he was respected in many circles of influence and was prepared to assist Cranfield, opening any door that was required. He encouraged local British clergy to partner with Cranfield, helping him in his work in visiting POW camps and providing resources for the German pastors.

Through Cranfield’s behind-thescenes work, individually and collectively with pastors, church leaders and church councils, individual organisations and government departments, the contribution that Cranfield made to the long-term rebuilding of the Confessing Church and through it, German society, was immense.

Cranfield organised resources for the spiritual, pastoral and emotional upbuilding of these…traumatised and demoralised pastors.

Bonhoeffer was executed behind the wire, Niemöller was incarcerated behind the wire, Cranfield ministered behind the wire, and Bell assisted outside the wire.

This article has only scratched the surface of the massive contribution made by Rev Professor Charles Ernest Burland Cranfield, an unsung hero of the Second World War.

Due to his academic brilliance, Cranfield moved into academia and was appointed a lecturer in Theology at the University of Durham in 1950. Later he was awarded a personal chair as Professor of Theology in 1978. At this time, as the nation remembers all those who paid the ultimate price in past conflicts, let us not be unmindful of the chaplains of our Church who serve in the armed forces.

Very Rev Dr Ian McNie is a former Moderator of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland.

Author’s note: My main source in writing this article was through the generosity of Charles Cranfield’s daughter, Mary, who shared with me personal information from original papers, letters and pamphlets belonging to her father, and summarised by her mother, Ruth, daughter of Thomas Bole, a minister of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland.