11 minute read

Saving Texas Freedom Colonies

By: Dr. Andrea Roberts, Texas A&M University With the

assistance of students in her 2020 More Than Monuments Course

Advertisement

Part 1: An Introduction to Texas Freedom Colonies

What are Freedom Colonies?

Freedom Colonies are places that were settled by formerly enslaved people during the Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras in Texas following Emancipation. From 1865-1930, African Americans accumulated land and founded 557 historic black settlements or Freedom Colonies. Freedom Colonies were intentional communities created largely in response to political and economic repression by mainstream white society.

In these places, Black Texans could much better avoid the perils of debt bondage, sharecropping, and racialized violence from white communities, and live largely self-sustaining, independent lives on their own property. (Sitton, T., & Conrad, J.H. 2005) Since their founding, Freedom Colony descendants have dispersed, and hundreds of settlements’ status and locations are unknown. Gentrification, cultural erasure, natural disasters, resource extraction, population loss, urban renewal, and land dispossession have all contributed to their decline. Freedom Colony descendants’ lack of access to technical assistance, ecological and economic vulnerability, and invisibility in public records has quickened the disappearance of these historic Texas communities.

While the name “Freedom Colonies” applies uniquely to Texas settlements, Freedmen’s settlements were by no means solely a Texas phenomenon. After the Civil War, independent black communities emerged across the South. However, in the present day, Freedom Colonies find themselves in a distinct position when contrasted with other black communities across the South. For example, many of the Freedmen’s settlements that receive scholarly or institutional attention, such as Tuskegee and Talladega, Alabama, Mound Bayou, Mississippi, and Rosewood and Eatonville, Florida, remain populated, have large anchor institutions like colleges, are well documented, and mapped. In contrast, many Texas Freedom Colonies were often never incorporated and have fledgling populations with have little documentation or legal authority to make planning decisions (Roberts, A., & Biazar, M. J. 2019).

Freedom Colonies located in urban areas, though well defined, often compete within larger political systems in which they are relegated to the category “neighborhood,” or are lumped into larger geographical areas based on racial census concentrations rather than being recognized as distinct, politically sovereign communities.

Freedom Colonies as Cultural Landscapes

A majority of known Freedom Colonies are located in the eastern half of Texas. Why? The eastern half of the state contained a majority of the farmland and plantations on which the formerly enslaved once worked. Further, these coastal and flood-prone areas were some of the few areas in which African Americans could obtain land through adverse possession or squatting. In other cases, though rare, former plantation owners willed land to their Black offspring. Though originally concentrated in rural areas, Freedom Colonies emerged on the edges of major cities. Due to urbanization and sprawl, today’s suburbs and major cities are founded atop Freedom Colonies. Common elements and characteristics of Texas Freedom Colonies’ cultural landscapes are their anchor institutions: schools, cemeteries, lodges, and churches. Cemeteries and churches are the most persistent elements in these landscapes. Often several Freedom Colonies accessed the same churches and schools. That is why clusters of homesteads usually best define the Freedom Colony settlement pattern. Finally, the shared belief or knowledge of a community having once existed in a specific area is passed on through storytelling and commemorative events.

Freedom colonies are not, however, static landscapes, but active communities composed of dispersed yet committed social and kinship networks who return to preserve historic churches, homesteads, Rosenwald Schools, and cemeteries. Gatherings for festivals, funerals, church services, homecomings and family reunions are times during which descendants of Freedom Colony founders celebrate their successes and plan for the future of the settlements’’ remaining extant features.

Identifying Freedom Colonies

A way to recognize or identify a Freedom Colony in a location would be to notice aspects of the natural landscape and the property types that remain, and to listen to residents define the borders, cultural landmarks, and the names they ascribe to their own communities. Freedom Colonies would commonly be found in bottomlands and floodplains, which were areas whites found less desirable for land ownership. The land may be muddy, near a water source, and in a lower elevation than other surrounding communities would. Other characteristics to identify a colony would be to look at the remaining buildings, assess what they are/were, and their time period of construction based on materials. A nearby cemetery or gravestones could also identify the evidence of a community, and by looking at the names, dates, and inscriptions, the observer could learn when formerly enslaved people lived in a given Freedom Colony (Sitton, T., & Conrad, J.H. 2005). Churches, particularly their cornerstones, provide helpful clues about local leaders and land owning families. Cross referencing these with county histories or personal archival data like funeral and church anniversary programs can reveal the names of settlements.

Cultural resource surveys, historical monographs, and academic theses are often the best written sources for information on Freedom Colonies locations because public and government records often provide little documentation of their existence. Archaeological surveys, while containing helpful historical information, often omit precise locations to prevent vandalism and looting. Floodplain and Texas Department of Transportation maps from the past sixty years at times contain the names of Freedom Colonies that later were removed when the population there became non-existent. Walking tours with residents and descendants of community founders are particularly important because these are often the only means of accessing and locating some Freedom Colonies.

Vulnerable Communities

Texas Freedom Colonies have a variety of factors working against them and threatening their existence. These plots of land are often officially undocumented plots in the government’s eyes, so land ownership is a blurred line. Complex systems of inheritance and division of land lead to divided homesteads with unclear legal understanding of who owns what; and third party actors can purchase individual parcels that destroy the integrity of the community. They are also vulnerable to being forgotten or undiscovered because most accounts of these colonies are from eyewitnesses and oral sharing, mostly by older generations of people, who are quickly disappearing or being forgotten. There is also the struggle to officially recognize these colonies through designation on the National Register of Historic Places, because there are often issues of defining the colonies within the official standards for designation. Another factor making these places vulnerable is their physical location coupled with a lack of maintenance. With limited access to their rural locations and the hazards of being in flood plains, most physical evidence of these Freedom Colonies are being destroyed (Sitton, T., & Conrad, J. H. 2005). There was also a turning point in Freedom Colonies during a decline in population during after-World War 2, part of a national trend of the Great Migration, violence, loss of building integrity, demolition, neglect, and red lining and segregationist zoning all over America (Texas Freedom Colonies).

Distribution of Freedom Colonies throughout the State

According to the Texas Freedom Colonies Project’s Atlas, there are 557 known place names. Of those some 357 Freedom Colony locations have been verified by way of a remaining feature (object, structure, site), census status, or other publicly available databases. However, through online crowd-sourcing and offline surveys, the Project has identified the names and locations for another fifty settlements not originally listed. While a majority fall within the eastern half of Texas, the true statewide distribution of Freedom Colony settlements is not yet known.

Part 2: Freedom Colony Documentation and Preservation

The Importance of

Research

Most Freedom Colony history is embedded in the memories of elders or buried in their historic cemeteries. Rarely did families maintain written documentation of their structures, cemetery maps, or communal land ownership records among kinship networks. Further, the absence of Freedom Colonies from the public record, land ownership instability, and declining building conditions require cultural resource managers to rely on creative approaches to identifying data sources to support documentation.

Freedom Colony documentation and preservation requires research methods associated with various disciplines. Due to the diversity in the conditions of Texas Freedom Colonies, those engaged in documentation and preservation must match the appropriate methods to the context. In some urban Freedom Colonies, houses and churches associated with a specific period of significance or settlement pattern are still intact. Architectural historians, architects, and preservationists might easily piece together the story of these places and even locate city records containing boundaries and names. In many rural Freedom Colonies, however, conditions may require social scientists with a different skills set because many remote rural settlements will only have cemeteries or churches remaining and very few full- time residents. Settlements with few remaining features and low populations may require historical archaeologists, cultural anthropologists, and sociologists: researchers skilled in oral history interviewing, archival research, participatory preservation and archaeology, and ethnography.

Engaging in Freedom Colony research is about more than just preservation, but a chance to reshape the narratives surrounding African American history in Texas and the country. Identification and documentation of Freedom Colonies often requires supplementing historical inquiry with the voices and perspectives of Black Texans. Research thus becomes not only a means for preserving buildings but also an all-inclusive documentation of placemaking and African American stories of survival, resilience, and self-determined community building that are evidence of their culturally specific relationship to land ownership after Enslavement (Clay History & Edu Svcs, 2019).

Ongoing Documentation, Interpretation, and Preservation Initiatives

According to Schuster’s Preserving the Built Heritage, there are five primary preservation instruments or “tools.” Ownership and operation of property are the first of these. Regulation of the land is the second tool. Incentives and disincentives are the third tools. Allocation and enforcement of property rights is the fourth tool that ties heavily into the first tool. Information and education is the fifth tool. Grassroots and community groups are working to preserve Freedom Colonies, but have difficulty accessing and applying the tools available to other communities. Universities often step into the gap to support these grassroots efforts while state agencies spearhead capacity building and public education projects. Some scholars involve descendants in their documentation processes. Descendants, lay historians, scholars, and grassroots preservation groups have initiated ongoing documentation initiatives taking place within Freedom Colonies. While some approaches employ sophisticated technologies, other approaches still relay on highly personal interactions with descendants, and others a mixture of both.

What follows are a variety of Freedom Colony documentation projects falling within all of these categories.

Grassroots Heritage Conservation: Cultural Traditions

Grassroots communities and groups host annual events such as homecomings that aim to celebrate the heritage of African American settlements and raise funds for further maintenance for continuous preservation. There is a common objective, which is to “commemorate the black settlement founders, work to reinvest in the areas deemed important, and maintain a network with other settlements in the region” (Walk-Morris, 2020). These annual events are full of music, storytelling, and remembrance of the history of the settlements and the family members who have been connected. During these events, elders share memories and event organizers design programs and corresponding booklets containing social histories of families, institutions and leaders from local Freedom Colonies. These events include extended and church families who come together and enjoy music and heritage, and contribute financially to stewardship efforts.

University and College Research Initiatives in Texas

At Texas A&M University, there are different projects and research centers that are contributing to the documentation and identification of Freedom Colonies like the Texas Freedom Colonies project, the Center for Housing and Urban Development, and the Center for Heritage Conservation.

Center for Heritage Conservation: Church and Cemetery Documentation.

The Center for Heritage Conservation conducts interdisciplinary research and projects on all aspects of built and natural heritage. Most recently, they have led documentation of Dabney Hill Missionary Church and Hockley Cemetery within Freedom Colonies. Center for Heritage Conservation website: arch.tamu.edu/impact/centers-institutes-outreach/chc

The Center for Housing and Urban Development: The Texas Freedom Colonies Project Atlas & Study.

The Texas Freedom Colonies Project records the names, locations, and origins stories of the Black settlements in Texas using an ArcGIS digital humanities platform. Dr. Andrea Roberts started the Texas Freedom Colonies project to preserve and protect Freedom Colonies facing ecological threats. Documenting disappearing settlements through crowdsourcing is one of The Project’s initiatives. The public can add information to the atlas via the web map application tool. To identify new Freedom Colonies, website visitors can complete one of two surveys or add a point directly to the map. The Texas Freedom Colonies Project website: thetexasfreedomcoloniesproject.com

The University of Texas Archaeological Site Documentation and Interpretation

The Antioch Colony site and the Ransom Williams archaeological sites are two projects in which Freedom Colony homesteads and daily life have been documented. A new exhibit (2020) at the Bullock Museum in Austin interprets several Freedom Colonies using artifacts, oral histories, and a new short documentary film including Antioch Colony located near Buda, Texas. Terri Myers and Maria Franklin led preservation efforts of the Ransom Williams archaeological site, located near the Travis-Hays county line. Their work included conducting oral history interviews of descendants. The site allows a glimpse into the lives of the formerly enslaved Ransom and Sarah Williams who settled forty acres and had nine children. The image plots the land where Ransom and Sarah Williams’ Farmstead was located. Artifacts (glass bottles, a marble, parts of a comb, a bone-handle knife, floral printed ceramic plates, decorative buttons, and toy gun) offer insight daily life. The Ransom Williams site was a precursor to several area Freedom Colonies that would follow, including Rose and Antioch Colony.

TAMU School of Law and Texas Freedom Colonies Project Partnership.

One the biggest challenges to maintaining settlement patterns is retaining family land ownership in Freedom Colonies. Much land was attained through adverse possession (squatting) or eventually lost through partition sales. Several formerly enslaved Freedom Colony residents avoided courthouses and as a result, much land ownership went unrecorded leaving clouded titles. Without continuous, stable ownership of farmland and homesteads, the cultural landscape dissipates. Heirs’ property is inherited land that is owned by two or more people as tenants-in-common. These properties are typically passed down without a will and without any sort of formal probate process. Ownership of this kind makes it difficult for the owners of the properties to leverage them for loans. Because of the unclear titles, displacement of the residents is also a common issue in their properties. Churches and schools on land without clear title also have difficulty qualifying for loans, grants or being listed on the National Register of Historic Places. A new partnership with The Texas A&M University School of Law will address the gap in education among Freedom Colony descendants about estate planning, land retention, and legal status. Intended to be a training session the webinars will be accompanies by fact sheets about property rights, historic preservation, and transfer of property.

The University of Texas School of Law hosted a clinic in Jasper County that was focused on helping to preserve the area as a Freedom Colony. The clinic helped the Community Family Historical Preservation Association (CFHPA) change its status from a limited liability company to a non-profit organization and helped to draft its founding documents and apply for federal tax exemptions. The UT law students also conducted some workshops on legal issues related to protecting the ownership of their land.

The UT School of Law also hosted an Entrepreneurship and Community Development Clinic on protecting and preserving African-American Cemeteries and developed a corresponding information booklet. The booklet describes cemetery research, applying for a historic cemetery designation, obtaining a historic marker, and registering the cemetery with the Texas Historic Sites Atlas. The document also provides information on forming organizations to protect and maintain the cemetery.

Recognition & Designation

National Register of Historic Places

Listing and registering Freedom Colonies as cultural properties in the National Register affords recognition as well as access to technical assistance. Listed properties also qualify for various federal grant programs for planning and rehabilitation, federal income tax credits, and preservation easements incentives tied to donations to nonprofit organizations. In addition, while National Register districts aren’t protected from local demolition laws, they are an important step toward protecting a sense of place and unity among property owners.

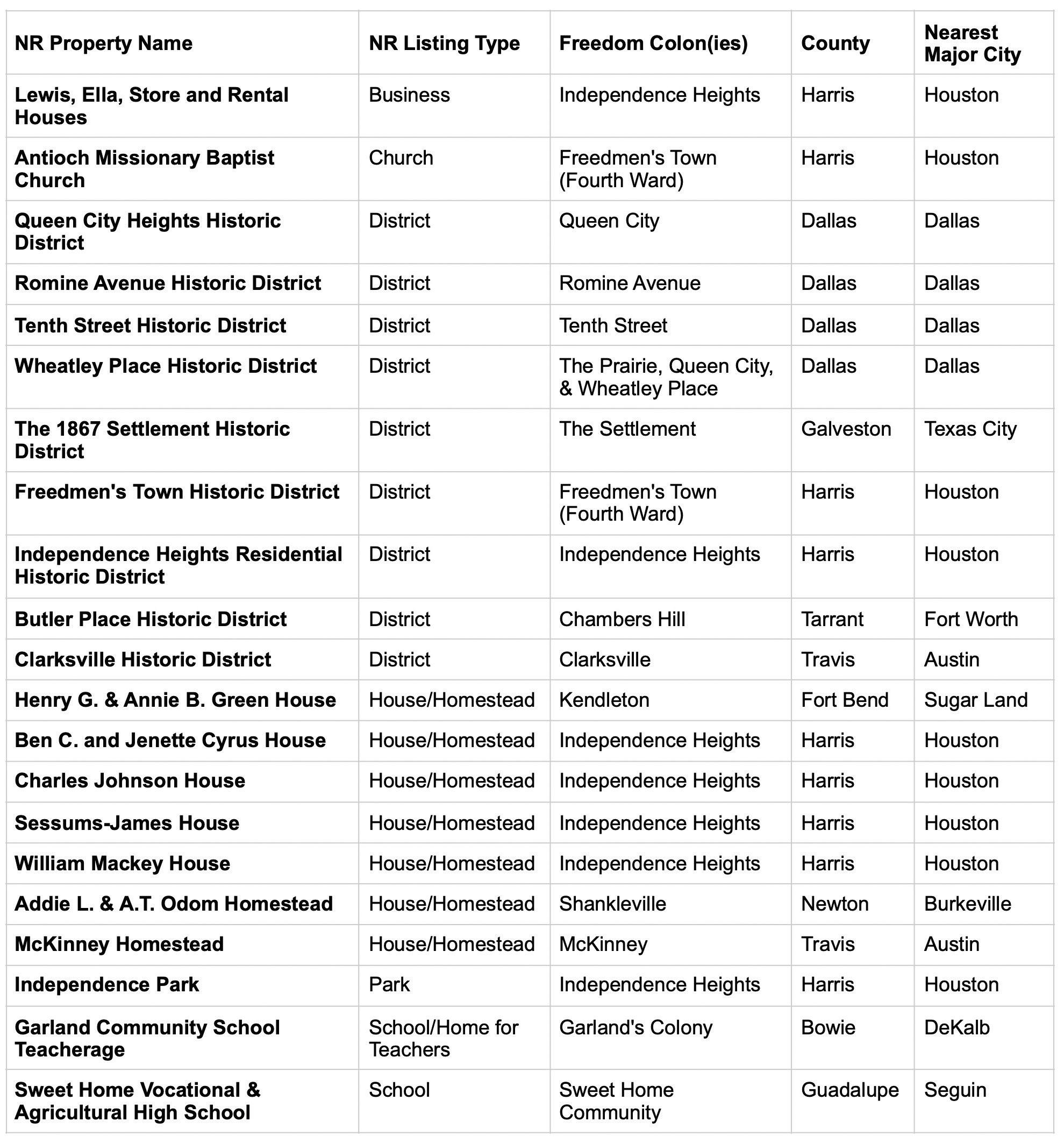

There are currently 77 listings on the National Register of Historic Places associated with the designation subcategory Ethnic: Black Heritage in Texas. Of those, 21 are located within known Freedom Colonies.

Listings in the table below are organized by property type, Freedom Colony location, county, and nearest major city. A majority of the listings were Districts (9) followed by rural and urban homesteads (7), schools (2), a church (1), a park (1) and (1) a business.