SELECTED EXCERPTS from

PENGUIN BOOKS

SUMMER 2021 FICTION

CONTENTS The Woman in the Purple Skirt by Natsuko Imamura

3

People Like Them by Samira Sedira

14

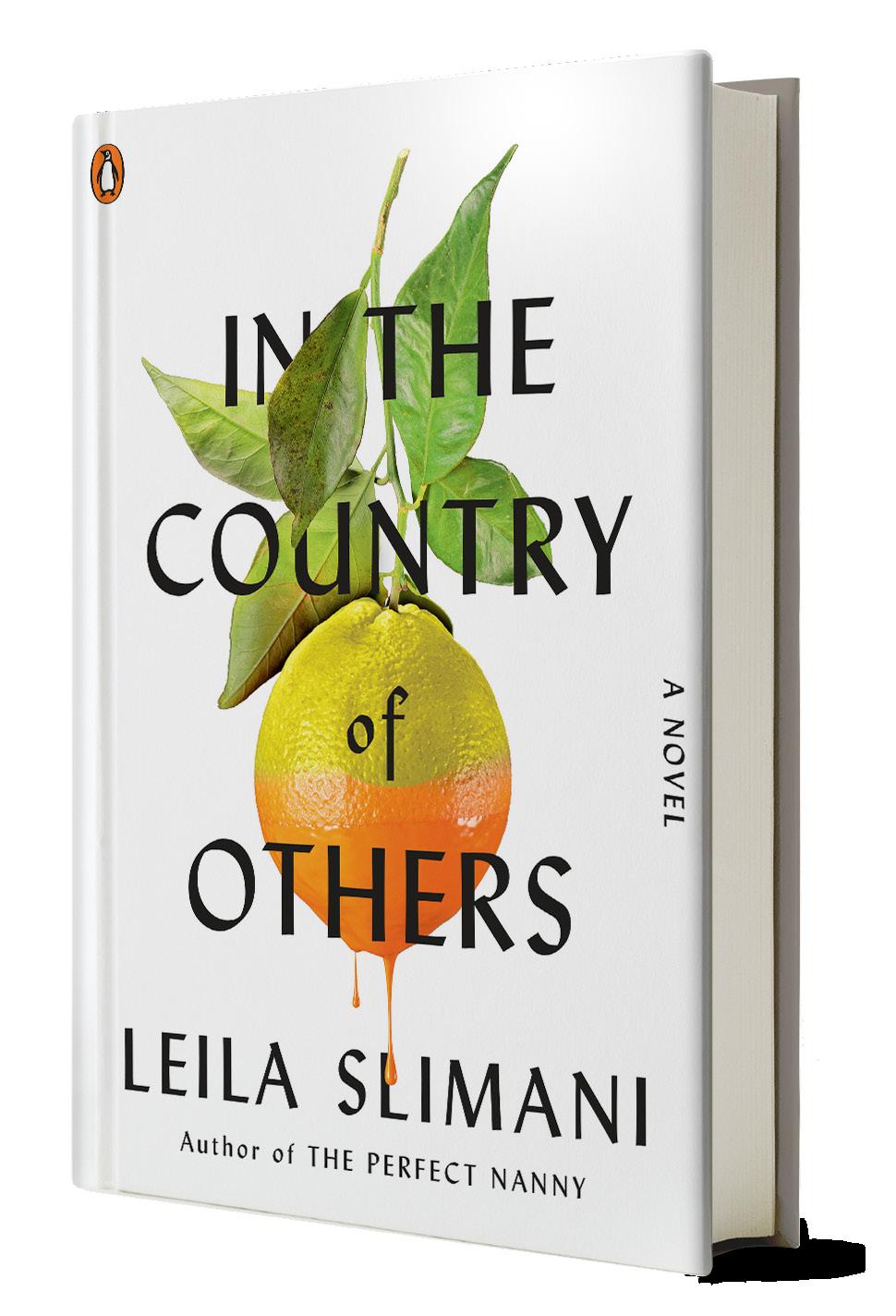

In the Country of Others by Leila Slimani

24

On sale June 8, 2021

Excerpt from The Woman in the Purple Skirt: There’s a person living not too far from me known as the Woman in the Purple Skirt. She only ever wears a purple-colored skirt––which is why she has this name. At first, I thought the Woman in the Purple Skirt must be just a girl. This is probably because she is small and delicate-looking, and because she has long hair that hangs down loosely over her shoulders. From a distance, you’d be forgiven for thinking she was about thirteen. But look carefully, from up close, and you see she’s not young––far from it. She has age spots on her cheeks, and that shoulder-length black hair is not glossy––it’s quite dry and stiff. About once a week, the Woman in the Purple Skirt goes to a bakery in the local shopping district and buys herself a little custard-filled cream bun. I always pretend to be taking my time deciding which pastries to buy, but in reality I’m getting a good look at her. And as I watch, I think to myself: She reminds me of somebody. But who? There’s even a bench, a special bench in the local park, that’s known as the Woman in the Purple Skirt’s Exclusively Reserved Seat. It’s one of three benches on the park’s south side––the farthest from the entrance. On certain days, I see the Woman in the Purple Skirt purchase her cream bun from the bakery, walk through the shopping district, and head straight for the park. The time is just past three in the afternoon. The evergreen oak trees that border the south side of the park protect the Exclusively Reserved Seat from the sun. The Woman in the Purple Skirt sits down in the middle of the bench and proceeds to eat her cream bun, holding one hand cupped underneath it, in case any of the custard filling spills onto her lap. After gazing for a second or two at the top of the bun, which is decorated with sliced almonds, she pops that too into her mouth, and proceeds to chew her last mouthful particularly slowly and lingeringly. As I watch her, I think to myself: I know: The Woman in the Purple Skirt bears a resemblance to my sister! Of course, I’m aware that she is not actually my sister. Their faces are totally different. But my sister was also one of those people who take their time with that last mouthful. Normally mildmannered, and happy to let me, the younger of the two of us, prevail in any of our sibling squabbles, my sister was a complete obsessive when it came to food. Her favorite was purin––the caramel custard cups available at every supermarket and convenience store. After eating it, she would often stare for ten, even twenty minutes at the caramel sauce, just dipping the little plastic spoon into it. I remember once, unable to bear it, swiping the cup out of her hands. “Give it to me, if you’re not going to eat it!” The fight that ensued––stuff pulled to the floor, furniture tipped over… I still have scars on my upper arms from her scratches, and I’m sure she still has the teethmarks I left on her thumb. It’s been twenty years since my parents divorced and the family broke apart. I wonder where my sister is now, and what she’s doing. Here I am thinking she still loves purin, but who knows, things change, and she too has probably changed. If the Woman in the Purple Skirt bears a resemblance to my sister, then maybe that means that she’s like me too…? No? But it’s not as if we have nothing in common. For now, let’s just say she’s the Woman in the Purple Skirt, and I am the Woman in the Yellow Cardigan. Unfortunately, no one knows or cares about the Woman in the Yellow Cardigan. That’s the difference between her and the Woman in the Purple Skirt. 4

When the Woman in the Yellow Cardigan goes out walking in the shopping district, nobody pays the slightest bit of attention. But when the Woman in the Purple Skirt goes out, it’s impossible not to pay attention. Nobody could ignore her. Say if she were to appear at the other end of the arcade. Everybody would immediately react––in one of four broad ways. Some people would pretend they hadn’t seen her, and carry on as before. Others would quickly move aside, to give her room to pass. Some would pump their fists, and look happy and hopeful. Others would do the opposite, and look fearful and downcast. (It’s one of the rules that two sightings in a single day means good luck, while three means bad luck). The most incredible thing about the Woman in the Purple Skirt is that, whatever reaction she gets from people around her, it makes absolutely no difference––she just continues on her way. Maintaining that same steady pace, lightly, quickly, smoothly, moving through the crowd. Strangely enough, even on weekends, at peak times when the streets are jam-packed with shoppers, she never walks into anyone, or bumps into anything––she just walks swiftly on, unimpeded. I would say that to be able to do that, she either has to be in possession of superb speed, agility, and fitness––or she has an extra eye fixed to her forehead, a third eye skillfully concealed under her bangs, rotating 360 degrees, giving her a good view of whatever’s coming her way. Whichever it is, it’s a trick well beyond the capability of the Woman in the Yellow Cardigan. She’s so skillful at avoiding any sort of collision that I can understand why you might get a rather eccentric person coming along who feels provoked––and gets the urge to purposely barge into her. Actually, there was one time when I myself succumbed to just such an urge. But of course, I was no more successful than anyone else. When was it? I think sometime in early spring. I pretended to be walking along innocently, minding my own business, and then, when the Woman in the Purple Skirt was just a few feet ahead of me, I suddenly upped my speed and walked very fast toward her. A pretty stupid thing to do, as I soon found out. When I was within inches of bumping into her, the Woman in the Purple Skirt simply tilted her body slightly to one side, and I went smack into the meat display cabinet in front of the butcher shop––fortunately escaping any serious physical injury, but still ending up with a huge repair bill from the butcher. That happened more than six months ago now. I’ve only just paid off that bill. And it wasn’t easy. I had to resort to sneaking my way into the bazaars held at a local primary school, having picked up anything that might possibly sell, to make whatever extra pennies I could. The first few times, I’d be thinking: Now look where your stupidity has landed you. Do not try anything like that ever again. It’s common knowledge that nobody who has attempted to collide with the Woman in the Purple Skirt has ever succeeded––don’t you know that? If not because of that third eye on her forehead, then because of how uncannily quick and fit she is. Even if privately you can’t help feeling that “fit” isn’t quite the right word to describe her… Actually, it occurs to me that the way she has of swerving smoothly through the crowds, avoiding all oncoming people, is very much like the way an ice skater glides around on the ice. She is like that girl who won a bronze medal a couple years ago at the Winter Olympics––the one in a blue skating dress who spoke in that strange way, like a little old lady, and who retired from skating to become a television entertainer and was selected last year to be a presenter on children’s TV; she was ranked Number One in the Children’s TV Popularity Rankings––yes, that girl. Admittedly, the Woman in the Purple Skirt is quite a bit older than she is, but (in my neighborhood at least) she is every bit as famous. 5

It’s true. The Woman in the Purple Skirt is a local celebrity. In the eyes not just of children, but of adults as well. From time to time, TV camera crews come by this area to conduct interviews with people on the street. But rather than thrusting a microphone in the faces of housewives and interrogating them about their dinner plans or their opinions on the rising price of vegetables, I’d like it if occasionally they directed questions at elderly people and children. They might ask: Have you ever heard of the Woman in the Purple Skirt? I’m sure nearly everyone would say: Yes, of course! There’s even a new game that the children have taken to playing. Whoever loses at Rock-Paper-Scissors now has to go up to the Woman in the Purple Skirt and give her a light tap. It’s a minor variation on the usual game, but they all get very excited about it. It takes place in the park. Any child who loses a round has to tiptoe up to the Woman in the Purple Skirt as she sits on her Exclusively Reserved Seat and give her a little tap on the shoulder. That’s all it is. Once the child has tapped her, he or she runs away laughing. They do this over and over again. Originally, the addition didn’t involve touching the Woman in the Purple Skirt but just approaching her and addressing her. The loser had to go over to her as she sat there and just say a few words. “Hello!” “Beautiful day!” Anything. That in itself was the source of huge amusement. Each child would skip up to her, say a word or two, and dash away, cackling with laughter. It’s only recently that the new twist was devised. The reason seems to have been simply that both sides had grown bored with the previous version. All they could think of to say to her was “Are you well?” “Nice weather!” Or at best something like Haa waa yuu? in English––which of course didn’t get a peep out of her. The Woman in the Purple Skirt sat absolutely still, her eyes lowered, but as time passed, she would yawn or pick at her nails. As I watched her languidly plucking the pilling off her sweater, it almost seemed that she was trying to challenge the children to think of something new. This new spin on the game, which the children came up with by forming a circle, putting their foreheads together, and thinking hard about how to break out of the old routine, is already showing signs of becoming the go-to version, but so far nobody’s said they’re tired of it. “Rock! Paper! Scissors!” they all yell. Up leaps the winner with a shout of triumph, while the loser wails with a look of misery. Meanwhile, there she sits, absolutely still, on her Exclusively Reserved Seat, her eyes lowered, her hands in her lap. It’s possible she’s not comfortable with this new rule. I wonder what’s going through her mind when she gets that little tap on her shoulder. I know I said the Woman in the Purple Skirt reminds me of my sister. But actually, I think I was wrong. And she’s not like that figure-skater-turned-celebrity either. The person she most reminds me of is Mei-chan, a friend I had in elementary school. A girl who used to wear her hair in long braids secured with red elastic bands. Mei-chan’s father came from China. Just a day or so before our elementary school graduation ceremony, Mei-chan’s entire family had to go back to Shanghai, the father’s home city. When the Woman in the Purple Skirt sits motionless on her bench, she reminds me of Mei-chan during swimming class. Not even looking at the rest of us as we swam around in the pool, but just sitting, hunched over, picking at her nails. Mei-chan? No… Could it be you? We lost touch after you returned to China, but … have you really come back all this way… to see me…?

6

Come on––don’t kid yourself. Mei-chan was a friend, but we were never actually close. We probably played together one or two times––at most. But Mei-chan was kind to me. I remember what she said about a picture I drew of a dog. “You’ve drawn that tail really well!” Child as I was, I felt so in awe of her. If anybody was good at drawing, it was Mei-chan. She always said she wanted to be a painter when she grew up. And that’s exactly what she became. Fuan-Chun Mei, the Chinese painter who was brought up in Japan, and who just three years ago came back to Japan and had a solo exhibition. I saw a newspaper article about it. The woman standing in front of her paintings and smiling was definitely Mei-chan, even if she was no longer the little girl who wore her hair in braids. Ah yes, that’s her, that’s Mei-chan: the same big bright eyes, the same beauty mark just below her nose. The Woman in the Purple Skirt has small eyes that look sunken and narrow. She has age spots, yes, but not a single beauty mark. If we’re talking about eyes, the Woman in the Purple Skirt reminds me of Arishima-san, my classmate in junior high school. Personality-wise, Arishima-san was probably one of a kind, but eye-wise, she is the spitting image. I was terrified of Arishima-san. She had her hair bleached blond like a real tough girl, she shoplifted, she extorted money from people, and she was violent. She carried a long knife like a Japanese sword everywhere she went. I think she was probably the most dangerous person I have ever met. Her parents, her teachers, even the police––no one knew what to do with her. I don’t know why, but she once gave me a stick of plum-flavored chewing gum. I felt a poke in my back and heard someone say, “Want some gum?” That was the first time I looked at Arishima-san head-on. Those small sunken narrow eyes, those downwardly sloping eyebrows… For a second, I didn’t know whom I was looking at. I took the gum without saying anything. Why didn’t I at least thank her? I assumed the gum was poisoned, and chucked it in a trash can in front of a sake shop on my way home. Why would it have been poisoned? I should have just started chewing it right away. The next day, I could have given her a piece of candy. Well, too late now. Arishima-san left school as soon as she could, after junior high, and immediately started hanging out with hoodlums. Rumor had it that she eventually got involved in pimping and drug-dealing, and threw herself into gangster life. She’s probably in jail now. On death row, maybe. Which means that the Woman in the Purple Skirt can’t be her. Oh, actually, there’s another person the Woman in the Purple Skirt reminds me of. She’s a regular commentator on afternoon TV shows. The manga artist who draws cutesy little cartoons about a ghost––and, just recently, illustrations for children’s books. As she always says, it sounds so much better to be an “illustrator” than a “cartoonist,” doesn’t it? She’s the one with the husband who is also a manga artist. What’s his name? I can’t remember. Oh no, wait. The person the Woman in the Purple Skirt really reminds me of is the cashier in the supermarket near where I used to live. The woman who one day asked out of the blue whether I was all right. It was when things had hit rock bottom for me: I almost collapsed as I took my change from her. The next day, when I went again to the supermarket, she clearly recognized me and called out a friendly greeting. I could never go back to that supermarket. But recently, on a visit to the library in my old neighborhood, I dropped by the supermarket, for old time’s

7

sake, and took a peek inside. There she stood, in her usual place by the cash register. She was absorbed in her work. I noticed a different badge on the front of her uniform. I think what I’m trying to say is that I’ve been wanting to become friends with the Woman in the Purple Skirt for a very long time. I should add that I’ve already checked out where the Woman in the Purple Skirt lives. I did that quite a long time ago. It’s a ramshackle old apartment building not too far from the park. And, of course, not far from the shopping district either. Part of the roof is covered in blue tarp, and the handrail for the outside stairs connecting the floors is brown with rust. The Woman in the Purple Skirt glides up the stairs without even touching the railing. Her apartment is the one in the back corner on the second floor, farthest from the stairs. Apartment Number 201. It’s this apartment that the Woman in the Purple Skirt leaves when she goes to work. I have an idea, you know, that the people in the shopping district assume she doesn’t work. And to be honest, that’s what I too thought. A woman like that, I said to myself––I bet you she’s unemployed. That’s what I assumed. But I was wrong. The Woman in the Purple Skirt is employed. How else would she be able to afford her cream bun, or, for that matter, her rent? But she doesn’t work full-time. Sometimes she is working, sometimes she is not. And her workplace seems to change over and over again. She’s had a job at a screw-making factory, a toothbrush-making factory, an eye-drop-bottle-making factory… The jobs all seem to be for just a few days, or at most a few weeks. She’ll be out of work for a really long time, then suddenly be employed for a whole month. I’ve written down her work record in my diary. Last year, in September, she was working. In October she didn’t work. In November she worked for the first half of the month only. In December she was working, but only for the first half of the month. This year, her first job started on the 10th of January. In February she worked. In March she worked. In April she didn’t work. In May, apart from the annual Golden Week holiday, she was working. In June she worked. In July she worked. In August she worked for the first half. In September she didn’t work. In October she worked on and off. And now, in November, it seems she is out of work. When she does work, it is always at a job that involves getting up at the break of dawn and returning in the late evening. She comes straight home, obviously shattered, without stopping off anywhere to get something for dinner. If she does have a rare day off, she stays shut up inside her apartment. Nowadays, I catch sight of her constantly, at all times of the day: sometimes in the park, sometimes in the shopping district. While it’s difficult to keep tabs on her every minute of every hour, from the look of it I’d say the Woman in the Purple Skirt is in good health. And if she’s in good health, you can be pretty certain she’s out of work. I want to become friends with the Woman in the Purple Skirt. But how? That’s all I can think about. But all that happens is that the days go by. It would be weird to go up to her and say “Hi” out of the blue. I’m willing to bet that in her entire life the Woman in the Purple Skirt has probably never had anyone tell her they’d like to get to know her. I know I haven’t. Does anyone ever have that said to them? It seems so forced. I just want to talk to her. It’s not as if I’m making a pass at her. 8

But how do I go about it? I think the first thing to do would be to introduce myself formally to her––in a way that wouldn’t feel too forced. Now, if we were students at the same school or coworkers in the same company, it might be possible. So here I am in the park. I am sitting on one of the three benches on the south side. The bench nearest the park entrance. In front of my face I’m holding yesterday’s newspaper. I picked it out of the garbage can a few minutes ago. The bench next to the bench next to mine is the Exclusively Reserved Seat. On the end of the seat lies a magazine of job listings, the type available for free at any convenience store. Less than ten minutes ago, the Woman in the Purple Skirt was making her purchase in the bakery. If I know anything about her daily routine, she always drops by the park on days she goes to the bakery. And sure enough, just as I finish reading an entry in the advice column about a man in his thirties in the second year of a sexless marriage wondering if he should get a divorce, I hear the sound of her footsteps. Hm. That was quick. I peer over the top of my newspaper. It’s a man dressed in an ordinary gray suit. Oh: so it wasn’t her after all. On second thought, the sound of his footsteps was quite different. He trudges past me, letting the soles of his shoes drag along the ground, clearly exhausted, and then plops himself down on the bench in the far corner. Very likely a salaryman from some office in the city, out paying courtesy calls to potential clients. I notice he carries a black briefcase. Let me guess. Having traipsed into every remotely promising shop in the shopping district with not a single taker, he is now going to steal a little time off on the sly to catch a snooze in the park. There are five benches total in this park (three on the south side, two on the north). You can always tell the ones who are first-time visitors by the bench they choose. I felt a little sorry for him, seeing how exhausted he was. But tough luck. It was time to get him to move. I went up to him to explain the situation, but he just glanced up at me and scowled. Even so, a reserved seat is a reserved seat. Rules are rules. I had no choice. I had to get him to give it up. I repeated what I’d said, several times, and, finally, the penny seemed to drop: He got up and moved to another bench, though with extreme reluctance. And just at this moment, out of the corner of my eye, I detected that someone else was approaching. This time it had to be her. I rushed back to my seat, and held my newspaper up in front of my face. The Woman in the Purple Skirt carried a single paper bag from the bakery. Seating herself on her Exclusively Reserved Seat, which had just this minute been vacated, she opened up the bag and drew out her purchase. The usual cream bun. It’s the kind of thing that is typically the subject of TV street interviews. “What did you buy today?” the interviewer asks, stopping shoppers who are carrying bags with the bakery logo and thrusting the microphone in their faces. The soft white loaf and the cream bun are the most common answers. And my answer, too, would be “a cream bun!” if anyone were to ask me. The distinctive features? Well, I’d say the custard filling, which has to have just the right degree of stiffness, and the delicately thin surrounding dough. Then there’s the sprinkling of sliced almonds on top. That’s what makes that satisfyingly crisp sound when you take a bite out of it.

9

M-m-unch. Crunch-crunch-crunch. Some almond pieces fell onto the Woman in the Purple Skirt’s skirt. Pitter-patter through the fingers of the hand she held underneath the bun as she ate. She didn’t notice this. She always looked off at a distant point in the sky as she ate her cream bun. Proof that she was concentrating. Her eyes and ears were closed to the world. That repeated crunching sound again. Nom-nom. Crunch-crunch. Yum. Delicious. She finished eating the bun, then balled up the paper bag, and her eye fell on the jobs magazine laid on the end of the bench. In an unhurried way she picked it up and started flicking through it. After flicking quickly through it once, she went back to the beginning, then flicked through it again, this time more slowly. There was a special feature in this issue on “Best Workplaces for Team Players.” It took up almost half the magazine. But that wasn’t important, no, skip that. Part-time Work in the Hospitality Industry, Part-time Work in Clothing and Retail… No, skip those too. The edges of the pages had different colors––blue, red, yellow, green––according to the type of work. The final pages, Night Work, were pink-edged. For some reason, she perused these pink pages at some length. No, not there. Look at the section preceding that, the one with the green-edged pages. That small box advertisement to the right of “Parcel sorters.” I’d circled it with a fluorescent marker. It ought to be obvious. Had she seen it––had she got the hint? The Woman in the Purple Skirt closed the magazine, rolled it up, got to her feet, and headed toward the garbage can. Oh, not to discard it, surely? The next minute, she switched the magazine to her other hand, tosses the paper bag in the garbage, and left. A few minutes later, the children came to the park, just out of school. Oh, wonder where she is? Restlessly, they scanned the park, then just stood there, clearly at a loss. A park that has just the Woman in the Yellow Cardigan seated in it clearly wasn’t scintillating enough for them. After a while, they started playing Rock-Paper-Scissors, but with none of the usual enthusiasm, and then, bereft of their usual playtime companion, they embarked on a game of safe-if-you’re-higher tag. The next day, the Woman in the Purple Skirt headed out to an interview. It was for a job in a soap-making factory. Clearly, the Woman in the Purple Skirt had not got the hint at all. Judging from past experience, if she were to pass the interview and get the job, this would mean that the soul-destroying daily grind would immediately begin. Every day she would be doing nothing but going back and forth between her apartment and her workplace. But if she didn’t get the job, then she would once again be loitering around the neighborhood. For the next week, and the week after that, the Woman in the Purple Skirt continued to hang around the neighborhood. Clearly, she hadn’t got the job. A few days later, the Woman in the Purple Skirt again headed out for a job interview. This time it was at a factory that made Chinese-style steamed pork buns. More evidence of her complete lack of judgment. Didn’t she know that if you want to work in food industry, the first thing they will look at is the condition of your nails and hair? No way is a woman with dry, dull, unkempt hair like a rat’s nest, and nails that are black, going to stand a chance. I knew she was going to fail––and of course that’s exactly what happened.

10

On the same day as the interview for that job, she also went for another interview, at a different company. This one was for a “stock controller––night shift.” I ask you: Why go for a job like that? I couldn’t help feeling puzzled. Didn’t she realize that on night shifts there are bound to be way more men than women? This is just a guess, but I get the feeling that the Woman in the Purple Skirt has an aversion to men. This is not to say she is a lesbian or anything like that. But if you’re working in an environment where you’re surrounded by men, well, inevitably, it takes its toll, doesn’t it? But not to worry, because she didn’t pass that interview, either. In the meantime, what with all this time-wasting, the period the Woman in the Purple Skirt had spent out of work has reached a new record. It was now a good two months. Of course, this was only since I started keeping track. Any day now, surely, her savings were going to be depleted. Was she still managing to pay her rent on time––not to mention her electricity and gas bills? Wasn’t her landlord going to start making preposterous demands, serving her with formal reminders, threatening to take her to court if she didn’t pay up immediately, demanding that she find a co-signer even though the original contract had not required a guarantor? Because once you find yourself in that kind of position, I’m afraid it’s a slippery slope. I’d say your only recourse is to stand your ground. That’s certainly what I had done. Recently I had decided to give up making any effort at all to pay my rent. It had all started with that stupid collision with that butcher’s display case. That’s when things had begun to go wrong. I had found myself in a fix: having to scrape together the regular repayments for the repair bill, but now as the months passed I slid deeper and deeper into arrears with my rent. I was still eking out an existence with the bit of extra money from selling odds and ends at the bazaars, but the income I gained from that was tiny. With the dire state of my finances, I didn’t stand a chance of paying both my rent and the repair bill. It was going to have to be one or the other. That said, every day I was still exploring ways I could escape from the debtors who I knew were going to come knocking at my door. I had investigated which coin lockers were in what train stations, with a view to transferring the few valuables I had left while I still could, before my landlord or one of his lawyers decided to make a forced entry into my apartment. I had identified a number of low-budget “capsule” hotels and manga coffee shops where I could take refuge if the need arose, and located a total of ten cheap boarding houses, in this prefecture and the adjacent one, where I could lie low for a while. If it ever came to that, I would happily share this information with the Woman in the Purple Skirt, but it doesn’t look as though we’ve quite got there yet. As of now, I haven’t seen any sign of threatening letters posted on the apartment door of the Woman in the Purple Skirt. Nor have I noticed anyone who appears to be her landlord staking out her building, waiting and watching for her to come home. At night I see the lights go on in her place, and the dial on her gas meter appears to be steadily ticking over. Evidently, she must be managing to pay her rent, and her electricity and heating bills. It would seem that her telephone, however, has been cut off. A few weeks into her job search, the Woman in the Purple Skirt started going out to the payphone in front of the convenience store to arrange job interviews.

11

When the Woman in the Purple Skirt goes to the convenience store, she never enters--she simply uses the payphone outside. It falls to me to enter the store. I go right inside, head for the corner where the magazine stands are, take the latest issue, and then leave it for her to find on her Exclusively Reserved Seat. The jobs magazine comes out on a weekly basis, unless it’s a double issue. But don’t imagine that the contents change just because there’s a new cover on the magazine every week. Workplaces that are continually short of staff place the same ad in every issue. While I didn’t accompany her to every interview, she applied for a number of other jobs too, after that spate of attempts, and often in tandem. She didn’t get any of them. Hardly surprising, considering the kind of jobs she chose––all totally unsuitable. Telephone receptionist, shopping plaza floor guide, et cetera. Would you believe that she even applied to be a waitress? Why would anyone hire someone as a waitress in a café who is happy to drink straight from the water fountain in her local park? Clearly, the repeated rejections were affecting her mind. Needless to say, the café told her immediately to get lost. And so, I am sorry to say, it was a good three months before the Woman in the Purple Skirt finally had a telephone interview to work at a place that was willing to consider hiring her. During that time, I had visited the convenience store to collect the jobs magazine for her a good ten times. It’s possible that I was to blame for this having taken her so long. Maybe I should have done more than simply circle listings with a highlighter––maybe I should have dog-eared the pages, or added little sticky notes. I’m sure there were any number of things I could have done better, but never mind--eventually, the Woman in the Purple Skirt came to the right decision. One evening, I saw her leave her apartment and make a beeline for the payphone outside the convenience store. I could see that she was holding a little scrap of paper tightly in her hand. Clutching the receiver, her face taut, she nodded several times as she listened. “Yes. Yes. I understand.” And then, “No. Yes. No, never.” She used a felt tip marker to write something on her palm. Was it “3,” perhaps, and then maybe “8”? Definitely numbers. Three o’clock on the eighth? The date and time of the interview? After she’d put down the receiver, her face remained tense. That didn’t surprise me. Every single one of her interviews up till now had ended in failure. Who wouldn’t be worried? But (not to get ahead of myself ) this time, at this workplace, I was sure it was going to be different. This time, I could guarantee one hundred percent that she would get the job. Because this was a workplace where they were always short of workers. Basically, anyone who applied was going to be welcomed with open arms. Even so, it would be good to go to this interview with, at the very least, a clean head of hair. She should trim her nails––and also apply a bit of lipstick, if she had such a thing. Because first impressions count, and little touches like those might make all the difference. Whenever I saw her, her hair was its usual mess––dull, dry, sticking out all over the place. I strongly suspected she was washing her hair with soap. I’d once had a part-time job at a shampoo factory, and I still had a fair number of shampoo samples from the huge stash I’d managed to collect. What about getting her to use some of my shampoo? It was just after midday. I was standing at what was pretty much the epicenter of the shopping district, holding a translucent plastic bag stuffed with every shampoo sample I had. This was the spot where TV camera

12

crews conducted their street interviews. There were always throngs of people, since the roads leading off the main shopping street, which ran on an east-west axis, led to a large supermarket on the right and a pachinko parlor on the left. Occasionally people hand out flyers there, but rarely product samples. Shoppers and passersby gladly accepted the freebies I was offering. One or two of them even took one, moved on, and then came back for another. It was gratifying to see that my efforts were being appreciated, but at this rate I was going to be left with none for the person who needed them most. To anyone who came back a second or third time, I now simply shook my head and turned them away. When I was down to five of my little packets of shampoo, the Woman in the Purple Skirt finally made an appearance in the shopping district. Noticing me handing out free samples, she cast a curious glance at the contents of my plastic bag. But she didn’t actually come over to me, and instead walked straight on by. Just as I was swiveling myself around to follow her and press a sample into her hands, I felt somebody grab me by the elbow. “Hey. Who are you? You’re not from around here, are you? Have you got permission from the Shopkeepers Association?” It was the proprietor of the Tatsumi sake store. The Tatsumi sake store is the oldest of all the stores in the shopping district. Its proprietor is also the president of the local Shopping District Shopkeepers Association. Normally a courteous, smiling sort of man, he proceeded to grill me in a very unfriendly tone. “Answer me. Come on! What are you handing out? What are those things? Let me have a look.” I shook my arm free of his grip. “Hey! Oi! Wait!” Normally, there is nothing I hate more than having to run, but this was one time I needed to. As I ran, I soon caught up with the Woman in the Purple Skirt, then left her far behind me. Once I’d made my way through the shopping district and was out on the main road, I kept running, repeatedly glancing over my shoulder, certain that the proprietor of the Tatsumi sake store was chasing after me. At a certain point, however, looking over my shoulder for the umpteenth time, I realized he was nowhere in sight. Eventually--much later, after dark--I made a special excursion to the apartment of the Woman in the Purple Skirt and hung my bag of shampoo samples on her doorknob. This is probably what I should have done in the first place. I put my ear up against the door and heard a faint, steady scrubbing sound. It seemed she was brushing her teeth. Well, that was a good sign. If she kept this up, maybe she was even going to wash her hair. Woman in the Purple Skirt! Give it your best shot! Get through the interview, and get the job!

13

On sale July 6, 2021

Excerpt from People Like Them: There’s no cemetery in Carmac. The dead are buried in the neighboring towns. But animal corpses are allowed. At the foot of a tree, or in the corner of a garden. Here, animals die where they lived. Men don’t have such luck. The small chapel overshadowed by a row of hundred-year-old plane trees doesn’t have much use anymore. People take refuge there in the summer, when the air becomes unbreathable. A haven of silence, coolness, and shade. Inside, thanks to the cold, moist stones, it feels like breathing deep within a cave. In the month of August in Carmac, everything burns. The grass, the trees, the children’s milky skin. The sun allows no respite. The animals drag too; the cows produce less milk; the dogs sniff at their food, then return to the shade, nauseous. In winter, it’s the opposite—everything freezes. Cloudy River, which crosses the valley, gets its name from that particularity: transparent and elusive in the summer, cloudy and iced over in winter. The village, built on either side of the river, is connected by a stone bridge called Two Donkeys Bridge. It has a grocer’s store, a post office, a town hall, a small bus station, a bakery, a café, a butcher shop, and a hairdresser. There’s also the old sawmill, whose machines haven’t whistled in over twenty years. Now, it serves as a hideaway for forest cats, when it snows, or when the females give birth. If you approach the village from the hillside road, it disappears into a vast pinewood, revealing its plunging valley only when you emerge from the last turn. The most peaceful season here is autumn, when the western wind sweeps away the last of the summer heat. Beginning in September, the sharp air cleanses the stone and rinses the undergrowth. The valley finally breathes. The autumn purge. White, clear, unrebellious sky. All that remains is the fragrance of wet grass, a smell of the world’s beginning with hints of pine resin. At dawn, the beams of the school bus announce a new day. Chilled, sleepy teens pile in. They’ll follow the river for a few miles, and then at the intersection, at the call of the town’s first murmurs, the bus will change direction. It’s the hour when the youngest go to the village school, and the adults to work. There are only two families of farmers left; all the others commute every day. Life is peaceful in Carmac, calm and orderly. But the most striking thing, here, when winter arrives, is the silence. A silence that spreads everywhere. A tense silence in which the slightest sound stands out: the footsteps of a stray dog crackling over dead leaves, a pinecone tumbling onto dry needles, a famished wild boar digging feebly at the ground, the naked branches of a chestnut tree rattling against each other when the wind picks up or crows fly by… And even sounds from miles away can be heard here. At night, if you listen closely, you can hear the tumble of rocks the weary mountain drops into small turquoise lakes, as milky and murky as blind eyes. When evening comes, when the smoke of fog intermingles with that of burnt fields and outside everything retreats, the houses fill with noise. Conversations are held between one room and another, the workday recounted, voices swelling, rising above the gurgling of the dishwasher, the sizzle of onions, the cries of a child who’s dreading bath time and the loneliness night brings. Maybe it’s because of that din that nobody heard anything the night they were killed. They say there were screams, gunshots, begging. But the chalet walls absorbed everything. Carnage behind closed doors. And nobody to save them. Yet outside, not the slightest breath of wind. Nothing but an interminable winter silence.

15

2 The first month I cried and couldn’t stop. For a long time, I tried to understand what had happened. Even now, I keep going through the story from beginning to end, trying not to forget a single detail. Sometimes one piece of the story will stick in my mind, to the point that I’m not able to sleep for several nights in a row. A detail that I unwind, analyze, dissect until I go mad, and which slips through my fingers as soon as I’m about to pierce its secret. These ruminations always seem ordinary enough, no different than the previous ones—that’s what I want to believe—but when night comes, they charge, the pain in the back of my head rousing my memories before casting me, alone, into a cold corner of the bed at dawn. That’s what happened last night: a question repeated without end, an unsolvable riddle that I turned over and over as the hours went clammily by. And yet, this question that kept me awake all night, that I tirelessly picked at without finding an answer, had already been asked of you clearly enough, by the prosecutor in the courtroom: Why did you go wash your hands in the frozen river after you butchered all the members of the Langlois family? It’s more than five hundred yards from the crime scene. Why not use one of the many sinks in the house? Anyone else would have done so. It’s logical. Anyone else would have used the sink in the bathroom or the kitchen, or even the toilet! But not you. You ran like a lunatic, with no fear of being seen, and once you reached the river, you pummeled at the ice because, as you said in your deposition, you absolutely had to wash your hands. You have to admit that’s a bit strange. Why did it have to be the river? Met with your hunted look, the prosecutor got annoyed. Stop staring at me like that, please, Mr. Guillot, and answer! His voice naturally carried far; a volume that cost him no effort. Meanwhile you said nothing, just stared at him obstinately. Only your lips twitched. Contradictory feelings waged war inside you: the desire to speak led disastrously to the inability to formulate the slightest explanation. Cornered, you found no other way out but to smile dumbly. In reality, you had no answer to give him, and your muteness echoed like the desolation that follows a major disaster. For the first time since your trial began, I felt pity for you. The prosecutor who had taken your reaction as a personal affront (no surprise there) immediately rose from his chair. In your position, and for your sake, Mr. Guillot, I would abstain from smiling! His deep voice brimming with natural authority had exploded in a roar with those words, prompting everyone to sit up abruptly in their seats. Your smile disappeared at once. The prosecutor swallowed before continuing. You ran out—that’s what you told the police officers—and, I’m quoting, “sprinted all the way to the river.” The prosecutor then raised his arms, like he was being held at gunpoint, and curled his upper lip. A sprint!? He paused. Who . . . He paused again . . . sprints, in the middle of winter, with temperatures below freezing, to go wash their hands soaked in the blood of their own victims? What exactly were you running from? Pause. He repeated, What were you running from? He obviously wasn’t expecting a response, seeing as he stopped for a few seconds to gather his thoughts, and then said, without even glancing at you:

16

The river was frozen but that didn’t stop you, Mr. Guillot. You banged at the thick crust of ice like a madman, first with the butt of your rifle, then with your fists, until it yielded. There was four inches of ice! Four inches, can you imagine?! It takes some rage to break through four inches, and you had just murdered an entire family with a baseball bat! You hit at the ice so hard that your hands split, “gushing blood.” Those are your words, are they not? The prosecutor approached the stand, slightly out of breath, arms hanging alongside his body. He had his back to the members of the jury, who were listening raptly. The prosecutor knew that nothing he said would escape their attention, and that a single word could suffice to reverse their final decision. As a representative of the law, he was responsible for people’s consciences. He looked at you intently, and then asked, Do you remember what you said during your deposition? You shrugged, a little lost. All right, I’ll tell you. You said, “My blood mixed with their blood. I couldn’t handle it.” The prosecutor shook his head, and with an air of feigned astonishment, he repeated, a little softer and overly articulating every word: “My blood mixed with their blood. I couldn’t handle it.” At that exact moment, he let out a mean snicker. It was odd, inappropriate. He must have realized it because his cheeks reddened. To contain his embarrassment, he resumed immediately, pointing at you with one stiff jerk of his chin to bring the attention back to you. And you added, to explain your revulsion, “I wasn’t there with my wife the times she gave birth. I’m not comfortable in hospitals. When I see blood, I pass out.” A long silence followed, filling the audience with a sense of dread and icy stupefaction. He had cornered you in a dead end. Trapped you like a rat. He couldn’t believe you were the kind of man to be afraid of blood. To him, it was a strategy aimed at softening the jurors. How could someone capable of killing five people tremble at the sight of blood? It seemed ludicrous, unimaginable. And yet. You really were horrified by blood. You could never bear to see the smallest drop. When one of our daughters skinned her knee or hand, you’d be paralyzed, watching her whimper, incapable of the slightest movement, and you invariably ended up calling me to clean the cut. Later, a psychiatric expert will corroborate the idea that a fear of blood doesn’t prevent someone from killing. We’ve already seen soldiers head bravely to the front and faint at the slightest prick of a vaccine shot! But at this stage of the trial, nobody wanted to believe you. You gritted your teeth, head down, face pale. Then, for some odd reason, the prosecutor abruptly turned towards me, as though I was a last resort. Clearly separating each word, he said, For someone who can’t handle the sight of blood, looks like you overcame your phobia easily enough. Laughter in the room. He was staring at me, at least I thought so until I realized that in reality, he didn’t actually see me. His gaze had lingered at random, and unfortunately it was in my direction that it had stopped. In the confused state in which I found myself, I felt guilty, the same as you. As if the mere fact of being your wife automatically incriminated me. Tears rose to my eyes. The calm veneer I had managed to maintain until then, at the cost of considerable effort, had cracked like dead wood. I was nothing but a piece of trembling humanity. A murderer by proxy. A murderer’s wife is reproached for everything: her composure when she should show more compassion; her hysteria when she should demonstrate restraint; her presence when she should disappear; her absence when she should have the decency to be there; and so on. The woman who one day becomes “the murderer’s

17

wife” shoulders a responsibility almost more damning than that of the murderer himself, because she wasn’t able to detect in time the vile beast slumbering inside her spouse. She lacked perceptiveness. And that’s what will bring about her fall from grace—her despicable lack of perceptiveness. The prosecutor finally looked away and stared at the ground, vaguely annoyed. His lips quivered. I thought I heard him mumble: Keep going, keep going. It was as if everything that had been said up to then had suddenly brought about some great inner turmoil in him. His back slumped. The powerful man he had forced himself to appear as gave way to an ordinary one, as disconcerted as anyone by the great mystery of human nature. He was standing in the middle of the courtroom, with everyone else seated, and I remember wondering, observing his black, perfectly waxed shoes, if he shone them himself or if someone did it for him. Later, during one of the hearings (I can’t remember the sequence anymore), the judge asked you to describe the night of the murders, while trying not to forget anything. Everything. Everything that you’d already told the police. The facts, nothing but the facts. The words didn’t come out right away; they had to be knocked around, shoved forward. But as soon as they were freed, you let them leap out of you, cold, without any particular modulations or emotions. None of it seemed to concern you, as though someone else had done the dirty work. Or as though you were reading a text from a prompter. Guided by that escapism logic, you let that “someone else” talk; the other, the true perpetrator. Later, the psychiatric expert called to the stand will explain that it’s not your “conscious self ” who killed. And to illustrate his point, he will cite Nietzsche: “I did that,” says my memory. “I could not have done that,” says my pride. No, none of it seemed to concern you. The memory of your confession still goes with me everywhere, like a black cloud above my head. I remember every one of your words, in detail, every single hesitation: I grabbed the bat handle with both hands, like this, I hit him hard behind the neck. The kid was having a snack at the big table, chocolate milk in a white bowl. A hard blow to the neck, like this, with both hands. I think that’s when his baby teeth came out . . . The police officers told me that they’d found two teeth between the floorboards. Baby teeth, they said . . . His head . . . his head fell forward onto the table, it made a sound, a loud sound, a . . . terrible noise; the bowl fell too, pieces all over the ground. I threw up a first time, I felt nauseous, couldn’t hold it back. He died instantly, I swear. I’m saying that for the family. He didn’t suffer, I swear. The oldest came down from her room yelling. She wasn’t happy. “What was that noise? Nono, what did you break now? I can never do my homework in peace!” She was waving her arms all over the place, annoyed. I ended up face to face with her in the living room. First she smiled. Odd, I thought, why is the kid smiling? And then, when she saw the blood on the bat, her eyes got black, black, and her mouth trembled. She looked around. “Where’s Nono?” she asked. Her face was anxious, her eyes, like a hunted animal . . . I didn’t answer. That’s when she saw him. His head on the table. The blood. The bowl on the ground. She understood. She said crying, “What’s wrong with Nono, why isn’t he moving?” She lifted her arms, she said, “I didn’t do anything, it’s a joke right, Constant, this is all a joke, isn’t it?” Sorry, I, are all these details useful? For the family, it . . . The judge encouraged you to continue with a nod.

18

Okay, well . . . I, I was saying that she was crying, and screaming, “Please, don’t, Constant, please, I want to see my maman, Maman, I want my maman.” She repeated “Maman” over and over, like she’d lost her mind, over and over. I raised the bat, I threw up again. She didn’t try to run, nothing, she just crossed her arms over her forehead, she crouched in front of me, and “Maman,” again, “I want my maman,” over and over. I closed my eyes so I could go through with it. I hit her. Again. And again. I, I opened my eyes, blood, lots of blood . . . she . . . she was dead. I threw up. Then I went to find the third one upstairs. She was hiding in the bathroom between the toilet bowl and a small cabinet, sucking her thumb. I told her to come out, to turn around—she obeyed without crying, nothing. I raised the bat high, real high, then against the neck again. Dead on the spot, like the first one. I threw up one last time, then I checked the time. Their parents would be back soon. I thought that it would be impossible with the bat, the father was too strong. I ran all the way to my garage, I grabbed the rifle, a double-barrel, I loaded it, then I went back to their house. The street was empty. In that weather, not a soul. I waited for them, hidden behind the door. It got dark. In winter here night comes on quick. In the silence, the dead bodies next to me, I . . . I was scared. I could hear their breathing. A corpse doesn’t breathe, I told myself, but nothing doing, I heard it. And the smell of blood . . . I almost threw up again, but I managed to keep it down that time. Finally the sound of a motor. I recognized it, it was them. The car doors slammed. The mother came in first, with bags of groceries. “We’re back, kids!”, she said, the father behind her. I didn’t stop to think, I kicked the door shut, and I shot them from behind. Him first. Then her. They collapsed, without realizing anything, without even having the reflex to turn around. It was over. I looked at them and I couldn’t move. I was trembling. That was the only thing I could do, tremble. I couldn’t stop trembling. I thought it would never stop. I looked out the window. Nobody. Blood, on my hands, and a smell of . . . a smell . . . it was death. That’s when I got the idea to go wash myself in the river. I wasn’t thinking of the cold, or the ice, or the distance, or of anybody who might see me. I didn’t think of any of that, just that I was trembling, and that my hands were covered in their blood, and that I had to get my legs to move so I could run to the river, and wash myself and . . . You didn’t have time to finish. A great cry of despair and terror, followed by a horrendous thud, made everyone freeze. Sylvia’s mother had just fainted in the courtroom. Her husband was straddling her, trying to revive his wife by caressing her forehead, as if that would suffice. That ridiculous position gave the scene a poignant theatricality, like this man and woman, who in the space of one night had lost everything that had given meaning to their lives, were characters in a bad dream, and we were their trembling witnesses. The hearing was adjourned for the day, and I hurried home, head buried in a thick scarf, haunted by your words. That night, alone in my bed, wrestling with an onslaught of anxiety, I started awake every hour, and each time that endless cry in the courtroom was echoing in my head. It was during that awful night that I realized that you had become inseparable from me, because I had loved you once, and because the story of your life had joined the story of mine in a tragedy beyond repair. 3 Everything began one Saturday in July of 2015. It was a terrible year bookended by terrorist attacks, whose televised images had plunged us into a state of utter shock. We watched them playing on a loop, stunned, unable to allow ourselves to believe them. In reality, fear was shaking our certainties along with our legs. For

19

reassurance, we comforted ourselves with the idea that city life clearly wasn’t for us, and that we were very lucky to live where we lived. Calm appeared to return with the arrival of summer. Giddy from the smell of freshly mown hay and whiffs of lilac, we hadn’t anticipated or even imagined the pale horror into which we would be plunged again only a few months later. Not only were we living almost outside of the world, we were also deaf to its upheavals. On that beautiful July Saturday, Simon and Lucie got married. The celebration took place in the courtyard of the family farm, in the shade of a large cedar tree, beneath its long low branches that touched the ground. Simon and I go a ways back, and knowing he was settling down at nearly thirty-seven delighted me as much as it did his parents, who had been sporting silly, fragile smiles ever since the marriage was announced, seemingly in constant fear of him changing his mind, which would have forced them to cancel the wedding and send everyone home. Simon was an endearing man, but his juvenile, boorish personality had delayed his entrance into the adult world. Until that day, he had oriented his life along two major axes: one, his work on the farm alongside his father, which he took very seriously; and two, weekend binges with his friends in pubs blanketed in sawdust. For God knows what vague reason, he had always loathed the idea of married life, and his imagining of it verged on a prison-like hell. Lucie, Simon’s wife, had miraculously succeeded where so many others had failed. The way she went about it remains, for all of us, a huge mystery. We had perfect weather, a day drenched in sunlight. In the late afternoon, the men, drunk from heat and brandy, had grabbed two castrated pigs from the trough where they were gorging themselves, and released them between the tables. The enormous creatures grunted and ran in every direction, chased by a pack of children with mauve cheeks whose growing elation, fueled by the adults’ laughter and shouting, gradually approached frenzy. In their anxious flight, the pigs trampled by, snouts wet and smeared with fresh barley, knocking over everything in their path. Simon’s wife, who had been on the dance floor, face beaming, abruptly found herself on the ground, legs spread beneath her white dress, mowed down by one of the pigs. Her small feet sticking out from taffeta spiked with dry burdock were bare, and her right big toe, shorter than the other four, was bleeding a little. She laughed, and hiccupped, and laughed, face crinkled, moving her head stupidly. Her mother, slurring from inebriation, and whose high bun was falling pathetically onto her forehead, leaned toward her and with one stretched-out hand begged her to get up, because Lushie, c’mon, a bride down for the count don’t look sho good! She didn’t seem to know that at this stage of the party, everyone was mixing up everyone else amid a general gaiety, and that etiquette, disarmed at the first glass of champagne, had long fled the scene. The bride wasn’t the center of attention anymore, despite the fact that she was slightly off-kilter and regularly getting twisted up in her long white veil. Even Simon himself was no longer focused on her. Standing on a chair before an exclusively male audience, he was chanting the chorus of “La Marseillaise,” one fist lifted toward the cedar tree’s highest branches, and encouraging everyone to sing with him: Aux armes citoyens, sortez vos aiguillons, fourrons, fourrons, qu’un blanc impur abreuve nos dondons! It was a terrible concert of wrong notes, whistles, and hollers. Marie, the old lady whom the village kids called Mama 92 (because she was ninety-two years old; they renamed her every year) plugged her ears with her two bony hands, and mumbled, sucking at her gums, Aie aie, what a racket! 20

We drank and ate late into the night. On the menu was leg of lamb, roast venison, potatoes in duck fat, thick slices of fresh sausage, garlic butter, cured sausage, smoked bacon, whole wheat bread, fresh walnuts, wild asparagus, and stuffed cabbage. As for alcohol, there was so much and so many kinds that I can’t remember what we drank, much less in what order. We were drunk even before we’d eaten our fill. Sitting at the tables, out of the sun, beneath the cedar branches, we sang at the top of our lungs, mouths full. The children laughed to see us reverting to childhood. We got carried away over nothing, invigorated by the joy of being together, all of us gifted at becoming emotional in no time at all. We took turns leaving to pee behind the farm, in copses of chamomile and lilac flowerbeds. In the silence interspersed with piercing moos, we could see the stony road dance, and the comfort of physically relieving ourselves added to our rapture. Long after the sun had set, our minds calmed by the night, I remember sitting on a chair at a big deserted table. It was midnight, maybe a little later. The air hadn’t cooled yet. My head was spinning, my tongue stiff as a piece of cardboard in my dry mouth. I had eaten too much, drank too much, talked too much. I had lost sight of you and the girls sometime late in the afternoon. I remember having spotted the children running in a pack from the courtyard to the granary and from the granary to the barn, never tiring. I had assumed they’d ended up falling asleep somewhere, our girls with them, piled one on top of the other in the hay like a litter of kittens lulled by the fresh air. I didn’t know where you were, but I wasn’t worried. I imagined you were chatting under a lime tree, or along the river, amid a cacophony of frogs. In a drunken, vegetative daze, chin in on my hands, I was contemplating what was left on the table: overflowing ashtrays, wine spilt on the paper tablecloth, half-eaten cream puffs. Many of the guests had gone home, but there were still enough of us to keep the party going. There were those talking quietly around the table, others (the oldest) dozing in their chairs, and then there were the ones smoking standing up while looking at the sky or else sluggishly twisting around on the dance floor, which was lit by a garland of paper lanterns. The newlyweds had disappeared, and their absence sparked a tender feeling of joy in us as we pictured them lying in the grass, brushing grasshoppers off their faces, intoxicated by kisses and the warm air. I’d learn later that, far from our romantic fantasies, our two lovebirds were in a deep sleep, drunk to the point of appearing dead, without having taken the time to undress or even take off their new shoes. I raised my head toward the sky; it was pure, without complication. A gentle breeze rustled the cedar branches. The moment struck me as so delectable that I closed my eyes. I went inside myself with as much delight as if I was slipping into a warm bath. I reached a primitive state of serenity, rocked by the music and whispers around the table. It was at that exact moment that they materialized, two silhouettes glued together coming toward us like some supernatural entity. The contrast between the depth of the night and the striking whiteness of their clothes no doubt reinforced the feeling of strangeness. Simon had told us that his future neighbors would be joining us, but when we didn’t see them arrive at either the town hall ceremony or the reception, we had all thought they’d preferred not to come, and then we eventually forgot about them. They approached hand in hand, in the thick night, without anyone seeming to notice them. The woman’s heels clicked in the air. The slightly forced confidence with which they had appeared one moment earlier slowly

21

disintegrated upon their contact with the warped cobblestones that covered the courtyard. Halfway across, they stopped, and I thought I detected some hesitation, but they resumed their walk toward us almost immediately. Only then could I see them clearly. The woman was wearing a flowy dress that fell along her body so nicely that I could hardly, and only reluctantly, take my eyes off her. The man had on a white linen suit and a gray shirt. His black face melted perfectly into the night, giving the illusion that his body was headless. I looked around and realized that nobody had noticed them, or else, more likely, that the busy day had made everyone disinclined to standard courtesies, so I stood up and went over to welcome the new arrivals. I quickly introduced myself and apologized for Simon’s absence. With a conspiratorial smile, encouraged by the reassuring darkness, I added, in a joking tone, that the young newlyweds surely had more important things to do. We shared a small forced laugh. As it should be, the man said to me, then turning to his wife, enveloping her in a gaze of immense tenderness, he added, It is a very special day . . . Moved by the thinly veiled reference to their own wedding, the woman nodded and then, discomfited by my presence, burst out laughing in joyful embarrassment. I suggested they find a spot at the table and drink a glass of wine. The other guests, zoned out in their little bubbles, didn’t pay any further attention to us. At least that’s how it seemed. Of course it was nothing of the sort. I would quickly understand, given the many questions I was asked the next day, that their fake indifference hid very real interest. I served them each a glass of wine, apologizing for not toasting with them. We’re only staying a few minutes, the man reassured me. He explained that given the late hour, they almost hadn’t come, but having promised Simon they’d be present at his wedding, they’d felt duty-bound to honor the invitation. His wife said she had family nearby, about ten miles away. We come here a lot on vacation. That was incidentally the reason they’d arrived so late; a family gathering had dragged on. I asked them where they had met Simon. At the bar in the village, not even a week ago, answered the man. We came to show our land to our architect. We’re going to build a house here. Yes, I’m aware, I responded. Simon told me that you bought a plot, not very far from my house, actually. Oh yeah? asked the man, delighted. Yeah, I answered. The house fifty yards down. The one with blue shutters, across the way? Yes, that one! Lovely to meet you, neighbor. That time, we shared a big laugh. The conversation continued a while longer. Then, quite naturally, it fizzled out and silence settled in between us. The man and the woman looked at each other and smiled, and their eyes said what their lips couldn’t express. I thought to myself that they must be a new couple, but in reality (I’d learn this later), they’d been married for fifteen years and had three children between seven and twelve years old. The comparison with my own relationship was inevitably painful. You and I didn’t look at each other with that intensity anymore, despite the love we shared. I don’t know why that observation made me a little sad. I quickly managed to convince 22

myself that their show of tenderness didn’t mean anything— that love could be modest, too, and that it wasn’t measured by how strongly it was displayed. When they stood to say goodbye, making me promise to give Simon and the new bride a hug from them, I felt relieved. I watched them disappear into the night, speeding up as though they were worried about missing an appointment. By their quickening steps, I guessed they were in a hurry to be alone again. My tense body relaxed. Nothing remained but immense fatigue.

23

On sale August 10, 2021

Excerpt from In the Country of Others: The first time Mathilde visited the farm, she thought: It’s too remote. The isolation made her anxious. He didn’t have a car back then, in 1947, so they crossed the fifteen miles that separated them from Meknes on an old cart, driven by a gypsy. Amine paid no attention to the discomfort of the wooden bench, nor to the dust that made his wife cough. He had eyes only for the landscape. He was eager to reach the estate that his father had left him. In 1935, after years spent working as a translator in the colonial army, Kadour Belhaj had purchased these hectares of stony ground. He’d told his son how he hoped to turn it into a flourishing farm that would feed generations of Belhaj children. Amine remembered his father’s gaze, his unwavering voice as he described his plans for the farm. Acres of vines, he’d explained, and whole hectares given over to cereals. They would build a house on the sunniest part of the hill, surrounded by fruit trees. The driveway would be lined with almond trees. Kadour was proud that this land would be his. ‘Our land!’ He uttered these words not in the way of nationalists or colonists – in the name of moral principles or an ideal – but simply as a landowner who was happy to own land. Old Belhaj wanted to be buried here, he wanted his children to be buried here; he wanted this land to nurture him and to be his last resting place. But he died in 1939, while his son was enrolled in the Spahi regiment, proudly wearing the burnous and the sirwal. Before leaving for the front, Amine – the eldest son, and now the head of the family – rented the land to a Frenchman born in Algeria. When Mathilde asked what he had died of, this father-in-law she’d never met, Amine touched his belly and silently nodded. Later, Mathilde found out what happened. After returning from Verdun, Kadour Belhaj suffered with chronic stomach pains that no Moroccan or European doctor was able to allay. So this man, who boasted of his love of reason, his education, his talent for foreign languages, dragged himself, weighed down by shame and despair, to a basement occupied by a chouafa. The sorceress tried to convince him that he was bewitched, that some powerful enemy was responsible for his suffering. She handed him a sheet of paper folded in four, containing some saffron-yellow powder. That evening he drank the remedy, diluted in water, and he died a few hours later in terrible pain. The family didn’t like to talk about it. They were ashamed of the father’s naivety and of the circumstances of his death, for the venerable officer had emptied his bowels on the patio of the house, his white djellaba soaked with shit. This day in April 1947, Amine smiled at Mathilde and told the driver to speed up. The gypsy rubbed his dirty bare feet together and whipped the mule even harder. Mathilde flinched. The man’s violence towards the animal revolted her. He clicked his tongue – ‘Ra!’ – and brought the lash down on the mule’s skeletal rump. It was spring and Mathilde was two months pregnant. The fields were covered in marigolds, mallows and starflowers. A cool breeze shook the sunflowers. On both sides of the road they saw the houses of French colonists, who had been here for twenty or thirty years and whose plantations stretched gently down to the horizon. Most of them came from Algeria and the authorities had granted them the best and biggest plots of land. Reaching out with one hand while using the other one as a visor to protect his eyes from the midday sun, Amine contemplated the vast expanse. Then he pointed to a line of cypresses that encircled the estate of Roger Mariani, who’d made his fortune as a winemaker and pig-farmer. From the road, they couldn’t see the

25

house, or even the acres of vines, but Mathilde had no difficulty imagining the wealth of this farmer, a wealth that filled her with hope for her own future. The serenely beautiful landscape reminded her of an engraving hung above the piano at her music teacher’s house in Mulhouse. She remembered this man telling her: ‘It’s in Tuscany, mademoiselle. Perhaps one day you will go to Italy.’ The mule came to a halt and started eating the grass that grew by the side of the road. The animal had no intention of climbing the slope that faced them, covered in large white stones. The driver stood up in a fury and began showering the mule with insults and lashes. Mathilde felt tears well behind her eyelids. Trying to hold them back, she pressed herself against her husband, who was irritated by her sensitivity. ‘What’s the matter with you?’ Amine said. ‘Tell him to stop hitting that poor mule.’ Mathilde put her hand on the gypsy’s shoulder and looked at him, like a child seeking to appease an angry parent. But the driver grew even more violent. He spat on the ground, raised his arm and said: ‘You want a good whipping too?’ The mood changed and so did the landscape. They came to the top of a shabby-looking hill. No flowers here, no cypresses, only a few stunted olive trees surviving amid the rocks and stones. The hill appeared hostile to life. We’re not in Tuscany anymore, thought Mathilde. This was more like the Wild West. They got off the cart and walked to a small, charmless little building with a corrugated-iron roof. It wasn’t a house, just a row of small, dark, damp rooms. There was only one window, located high up the wall to prevent vermin getting in, and it let through the barest hint of daylight. On the walls, Mathilde noticed large greenish stains caused by the recent rains. The former tenant had lived alone; his wife had gone back to live in Nimes after losing a child and he’d never bothered making the house more attractive. It was not a family home. Despite the warmth of the air, Mathilde felt chilled. When Amine told her his plans, she was filled with anxiety. * She had felt the same dismay when she first landed in Rabat, on 1 March 1946. Despite the desperately blue sky, despite the joy of seeing her husband again and the pride of having escaped her fate, she was afraid. It had taken her two days to get there. From Strasbourg to Paris, from Paris to Marseille, then from Marseille to Algiers, where she’d boarded an old Junkers and thought she was going to die. Sitting on a hard bench, among men with eyes wearied from years of war, she’d struggled not to scream. During the flight she wept, vomited, prayed. In her mouth she tasted the mingled flavours of bile and salt. She was sad, not so much at the idea of dying above Africa as at that of appearing on the dock to meet the love of her life in a wrinkled, vomit-stained dress. At last she landed, safe and sound, and Amine was there, more handsome than ever, under a sky so profoundly blue that it looked as though it had been washed in the sea. Her husband kissed her on both cheeks, aware of the other passengers watching him. He seized her right arm in a way that was simultaneously sensual and threatening. He seemed to want to control her. They took a taxi and Mathilde nestled close to Amine’s body, which she could tell was finally tense with desire, hungry for her. ‘We’re staying in the hotel tonight,’ he told the driver and, as if trying to defend his

26

morality, added: ‘This is my wife. She just arrived.’ Rabat was a small city, white and solar, with an elegance that surprised Mathilde. She stared rapturously at the art deco facades of the buildings in the city centre and pressed her nose to the glass to get a better view of the pretty women who walked along the Cours Lyautey wearing gloves that matched their hats and shoes. Everywhere she looked, she saw building sites, with men in rags waiting outside to ask for work. She saw nuns walking beside two peasants, who carried bundles of sticks on their backs. A little girl, her hair cut like a boy’s, laughed as she rode a donkey led by a black man. For the first time in her life, Mathilde breathed the salty wind of the Atlantic. The light dimmed, it grew pink and velvet. She felt sleepy and she was just about to lean her head on her husband’s shoulder when he announced that they’d arrived. They didn’t leave their room for two days. Mathilde, normally so curious about other people and the outside world, refused to open the shutters. She never wearied of Amine’s hands, his mouth, the smell of his skin, which – she understood now – was somehow connected with the air of this land. She was completely bewitched by him and begged him to stay inside her for as long as possible, even when they were falling asleep or talking. Mathilde’s mother said it was suffering and shame that brought back to us the memory of our animal condition. But nobody had ever told her about this pleasure. During the war, all those nights of desolation and sadness, Mathilde had made herself come in the freezing bed in her upstairs room. She would run there whenever the air-raid sirens wailed, whenever she heard the hum of an aeroplane, not for her survival but to quench her desire. Every time she was frightened, she went up to her bedroom. The door didn’t lock, but she didn’t care if anyone walked in on her. Besides, the others liked to gather in bunkers and basements; they wanted to die huddled together, like animals. She lay on her bed, and coming was the only way she could calm her fear, control it, gain some sort of power of the war. Lying on the dirty sheets, she thought about the men crossing plains all over the continent, armed with rifles, men who were missing women just like she was missing a man. And while she rubbed her clitoris, she imagined the immensity of that unquenched desire, that hunger for love and possession that had seized the entire planet. The idea of this infinite lust plunged her into a state of ecstasy. She threw back her head and, eyes bulging, imagined legions of men running to her, taking her, thanking her. For her, fear and pleasure were all mixed up and in moments of danger this was always her first thought. After two days and two nights, Amine almost had to drag her out of bed, half-dead from hunger and thirst, before she would agree to eat lunch with him on the hotel terrace. Even there, her heart warmed by wine, she thought about how Amine would soon fill the space between her thighs. But her husband’s expression was serious now. Eating with his hands, he devoured half a chicken and tried to talk about the future. He didn’t go back up to the room with her and grew offended when she suggested that they take a nap. Several times, he absented himself to make telephone calls. When she asked him who he was talking to or when they would leave Rabat and the hotel, his answers were vague. ‘Everything will be fine,’ he told her. ‘I’m going to arrange everything.’ A week later, after an afternoon that Mathilde had spent alone, he returned to the room looking nervous and vexed. Mathilde covered him with caresses, she sat in his lap. He took a sip from the glass of beer she’d poured for him and said: ‘I have some bad news. We’re going to have to wait a few months before we can