A CONVERSATION WITH ELEANOR SHEARER

This is your first novel. How long have you been working on it? And what inspired you to write River Sing Me Home ?

This novel was inspired by the women in the Caribbean who really did go and try to find their stolen children after slavery ended. I first learned about these women at an exhibition I went to when I was sixteen, so it was almost ten years between having the initial idea and actually setting out to write the novel. The story of these women stayed with me all those years, because I thought it was such a powerful illustration of the way people in the Caribbean resisted slavery and resisted its destruction of their families. But it wasn’t until 2020 and the pandemic that I started writing in earnest. I was lucky enough to have a job where I was working from home, and I thought, I’ll never have more free time than I do now, so if I don’t write this book now, I never will!

River Sing Me Home was influenced by a true story. Can you tell us more about that?

When I was sixteen, I went to an exhibition called Making Freedom, that was put on by the Windrush Foundation, a charity that celebrates the contribution of Caribbean people to the UK. Part of the exhibition mentioned that, when slavery ended, there were women who left their plantations to try to find the children who were taken from them and sold away. This was very common during slavery, which was about destroying people’s right to connect with their own ancestry and their descendants. The image of these women setting out to repair what slavery had worked so hard to destroy was so powerful that it stayed with me for years.

And I was lucky enough, about five years later, to meet the head of the Windrush Foundation, and I mentioned how much I had been moved by this story in the exhibition. He gave me a book called To Shoot Hard Labour, which is an oral history of a man called Samuel Smith, born in Antigua in the 1870s. He talks about his great-

grandmother, Mother Rachael, trying to find one of her daughters after emancipation. Mother Rachael helped inspire the story of Rachel in River Sing Me Home.

When I started writing River Sing Me Home, I realized how much the work I had already done without the novel in mind could support me. I did a masters degree in politics and I focused on the history of slavery and the politics of reparations, and I did fieldwork in the Caribbean. A lot of that work formed the backbone of the historical detail of the novel. But I also read some additional books, particularly around the 1823 Demerara rebellion that features in the novel, and around the history of Barbados and Trinidad.

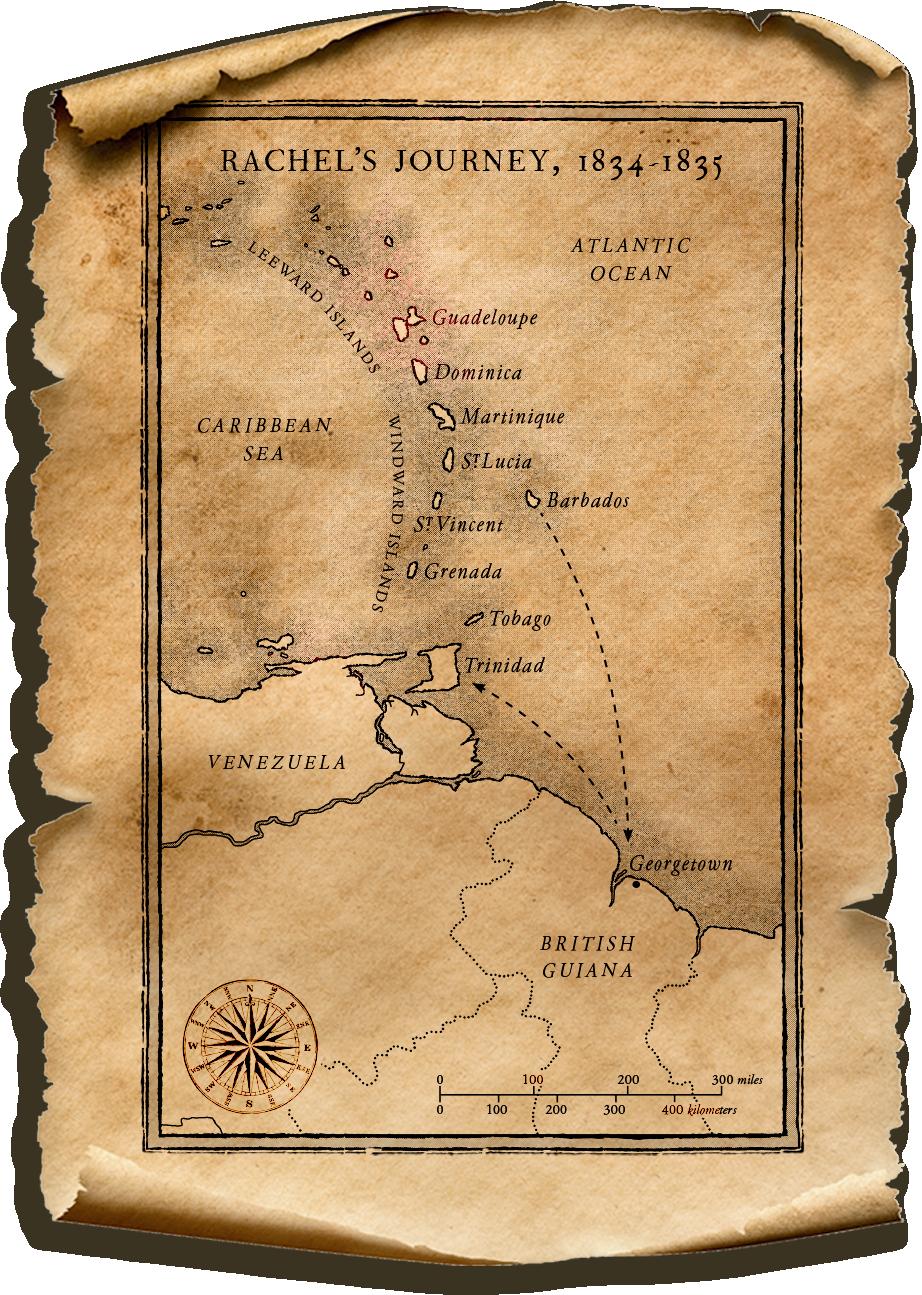

Because I was writing during the pandemic and couldn’t travel, I also spent a lot of time looking at old videos and photos of my previous trips to the Caribbean to try and recall the way it feels to be there. And I spent a lot of time on Google Earth and finding old maps of the locations in the novel, thinking about the different parts of Rachel’s journey and what she would see along the way. Finally, almost all the characters in the novel have names that I pulled from actual registers of enslaved people. Rachel’s daughters’ names are all found on a memorial in the Cave Hill campus in the University of the West Indies that I visited in 2018, and other characters—including Nobody— are pulled from the digital records that I found on Ancestry.com.

The work I did during my master’s was so critical to shaping the novel. Many of the themes I explore in the novel—like family, memory, and what it means to be free—are all ideas I explored in my master’s research. The point of my research was to show that slavery has had a lasting impact on the Caribbean not just materially but

What was your research process like? And what was the most surprising or unexpected discovery you made while researching?

You’ve earned a master’s degree in Politics at the University of Oxford, and studied the legacy of slavery and the case for reparations. How did you utilize your background to shape this story?

psychologically. Many people I spoke to in my fieldwork felt like the family separations commonplace during slavery had left lasting scars, with families in the Caribbean later separated by economic migration as people went to work on the Panama Canal, or in England, or in the US and Canada.

Also, my research taught me to have a more nuanced view of reparations. When I spoke to activists in the Caribbean, they were clear that while they do want compensation and apologies from the UK, they also feel a sense of agency and the ability to do their own community work to heal from the past. It was important to me to write a novel that reflected that sense of agency, and showed Caribbean people resisting and making freedom for themselves.

My fieldwork inspired me because of the stories people told about Caribbean history. For example, one of my mother’s cousins told me about how our family used to live on land that was occupied by maroons—runaway slaves. And in Barbados I heard more from historians at the University of the West Indies about Bussa, who led a slave rebellion in 1816. The fact that people wanted to center slave resistance in the stories about the past inspired me to write a book where Rachel and center her children all, in different ways, resist and make freedom for themselves. But I was also told about the ambivalence of emancipation. I spoke to archivist in St. Lucia who told me about how little conditions changed on the plantations when the slaves were freed, and about the apprenticeship system and the false promise of freedom in 1834. Today, the Caribbean celebrates 1838 as Emancipation Day, coinciding with the end of apprenticeships, rather than the Emancipation Act in 1834.

Your fieldwork in St. Lucia and Barbados helped inform River Sing Me Home . How did these experiences tie into the novel?

In addition to your studies and fieldwork, the idea of a family pieced back together is a personal one. Can you tell us more about your family ties to the Windrush generation?

My grandparents came to the UK in 1959 from St. Lucia as part of the Windrush generation. At the time, many Caribbean countries were still British colonies, and facing postwar labor shortages, the UK invited Caribbean people to come and live and work in the country. And my family was separated twice over, because my grandfather was actually born in Barbados, but he left his family there when he was fourteen and moved to St. Lucia and completely cut off contact with them. His mother and most of his siblings died never knowing what had happened to him. There was only one sister still living when he retired back to St. Lucia in his seventies, and they were able to meet once before he passed away. On my last trip to the Caribbean, I was able to meet my great-aunt for the first time, and it gave me hope that even when families are scattered, it is never too late for reconnection.

I have a huge amount of respect for art about slavery that engages, unflinchingly, with its full horrors. But I always saw River Sing Me Home as a different kind of novel. Not about slavery, but about what comes after. I think we need to make space for art that is also about love and joy even in a period where so many suffered, because people would still have been experiencing love and joy even then. And because of the fact that slavery worked so hard to destroy people’s families, writing about a mother who refuses that destruction was important to me. I see it as such an act of bravery to do what many Caribbean women did, and a powerful symbol of resistance.

This book tackles a little-understood time in Caribbean history and offers a revelatory look at the ambiguities of British Emancipation, but it is also a story of family, love, hope, and resilience. Can you speak to the importance of including these themes into the overall plot?

Rachel’s journey to find her children takes her to Barbados by river, deep into the forest of British Guiana, and finally across the sea to Trinidad. On her journey, she stumbles upon both a free village and a maroon community. Can you tell

Throughout the Caribbean, people resisted slavery by running away. But, depending on the geography of the country, this could look very different in different places. In somewhere like Barbados, where Rachel’s journey begins, almost all the land was settled by the colonists, and so there was nowhere to hide except in larger towns where people hoped to blend in and avoid capture. But in places with mountains or large forests, it was much easier for maroons to set up their own villages. In Jamaica, the maroons in the mountains were famous for signing an agreement with the British to achieve recognition, so impossible would it have been for them to be recaptured. Given the themes of freedom in River Sing Me Home, I knew as soon as I started writing it that I wanted to represent the maroons in the novel.

The free villages were places where, after emancipation, people lived and worked away from the plantations. They were common in places like Trinidad that were not so densely settled. I drew inspiration from Eric Williams’ History of Trinidad as well as the oral history book To Shoot Hard Labour, where Samuel Smith, born in Antigua in 1877, lived for a while with his family in a free village. These places were slightly more common after the end of apprenticeships when people were less tied to the plantations, so I took slight liberties with timelines to have Rachel come upon one. But as with the maroons, I wanted the novel to reflect all the different ways that people built communities away from slavery, and found freedom in these places.

us what these are, and what it was like to incorporate these different areas and facets of history into the book?

With music and song playing such an important role in the novel, I wanted a title that reflected this. But I also wanted to capture that the Caribbean landscape and the natural world are at the heart of this story. Finally, having the word “home” feels emotionally resonant, hinting that this is a story about family and love.

What do you hope readers take away from River Sing Me Home ?

I hope readers come away admiring the bravery of the people in the Caribbean who resisted slavery and colonialism in so many ways—the real people who inspired the stories of Rachel and her children and the characters she meets along the way. I hope they see River Sing Me Home as a novel that does not shy away from the brutality of slavery, but that is about more than just those brutalities. I hope they feel a sense of hope and love, too—about slavery, but also about what comes after. I think we need to make space for art that is also about love and joy even in a period where so many suffered, because people would still have been experiencing love and joy, even then. And because of the fact that slavery worked so hard to destroy people’s families, writing about a mother who refuses that destruction was important to me. I see it as such an act of bravery to do what many Caribbean women did, and a powerful symbol of resistance.

Eleanor Shearer

is a mixed-race writer and the granddaughter of Windrush generation immigrants. She splits her time between London and Ramsgate on the English coast so that she never has to go too long without seeing the sea. For her master’s degree in politics at the University of Oxford, Eleanor stud ied the legacy of slavery and the case for repara tions, and her fieldwork in St. Lucia and Barbados helped inspire her first novel.

What significance does the title River Sing Me Home have to the story?

1.

Questions for Discussion

“Rachel did not mind that she lacked Hope’s hard outlines and clear sense of self. That was how she had chosen to survive—by letting little pieces of herself fall away without resistance.” What do you make of Rachel’s character and of her at titude to survival? Do you think her attitude changes during the novel?

2. What does Rachel’s journey say about motherhood? What do you think Rachel learns about being a mother over the course of the novel?

3. Each of Rachel’s children chooses a different path out of slavery. Are they all, in some sense, free? Are some paths better than others?

4. Lots of characters in this novel get a chance to tell small fragments of their stories. Why might this telling be important? What role do these stories play in Rachel’s journey? Are they able to teach her something about herself?

5. Rachel does not mention much about the fathers of her children. Do you think this is deliberate? Are there any clues in the text as to who the fathers might be?

6. What roles do music and song play in the novel?

7. Thomas Augustus tells Rachel that in the runaway village, some people love to tell and retell the past, while others just want to forget it. How does the novel deal with the themes of remembering and forgetting? Do you think there is a right choice between dwelling on the past and leaving it behind?

8. What do you make of the character of Mary Grace? Why do you think Nobody is so drawn to her, and her to him?

9. The natural world plays a significant role in the novel. How does the landscape of the Caribbean relate to Rachel’s journey? Do you think Rachel sees nature as benevolent, malign, or something in-between?