10 minute read

Repertoire: Cultural Keyboard Warriors versus Music Teachers

Professor Martin Fautley

One of the issues that always seems to raise its head in music is that of the materials employed in teaching and learning. This subject has become so contentious that in some quarters it creates arguments all of its own. As one of the academics who authored the report for Youth Music that engendered the “Stormzy versus Mozart” debacle when it came out (Kinsella et al., 2019), I still bear the scars of that encounter! But what was, or is, all the fuss about? In this article I will try and unpick some of these issues, and offer some very personal thoughts as to what is going on.

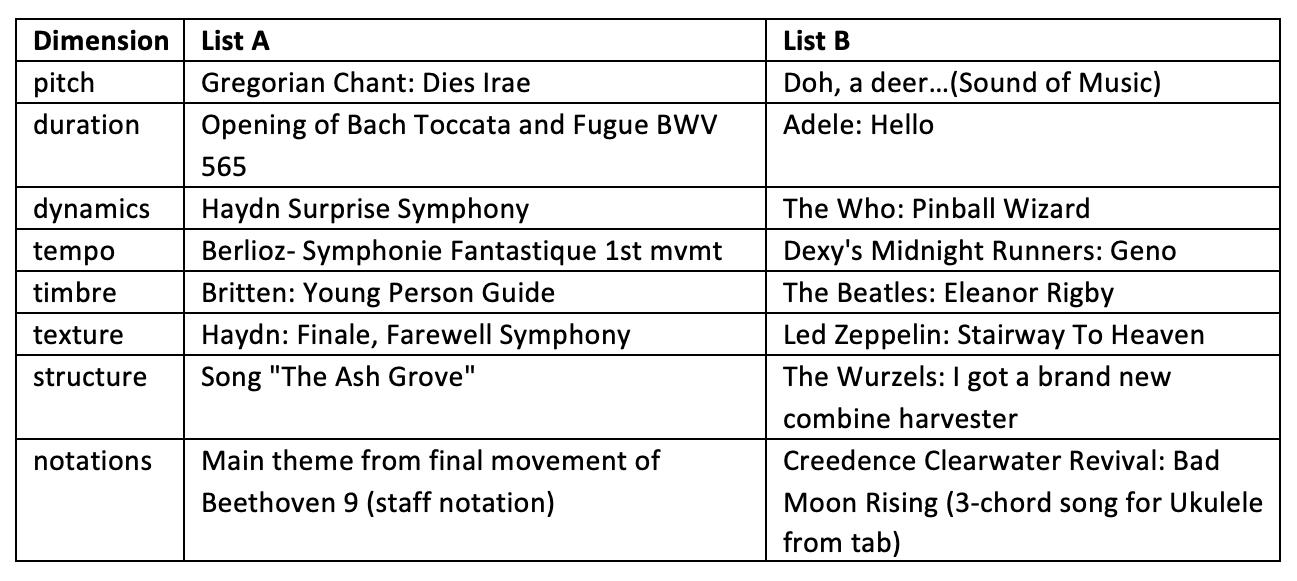

Let us start by revisiting the National Curriculum for music, in particular the things which used to be called the ‘elements of music’, but are now known as the ‘inter-related dimensions’, namely pitch, duration, dynamics, tempo, timbre, texture, structure, and appropriate musical notations. These are all conceptual building blocks upon which music is based, and whilst there are debates about whether they can be separated one from another (which I don’t want to get into here), nonetheless these can be recognised as just about essential in many musical cultures, and important concepts to teach and learn. And it is with this matter that issues begin. Here, for example, is a quick back-of-an-envelope list of the inter-related dimensions, and then two lists of music which might be used to teach them:

Now, I will admit that this is a very simplistic set of lists, but what do you spot about the differences between list A and list B? Hopefully I have engineered it so that the answer is obvious! List A contains examples of pieces from western classical music, list B uses popular music. Now, I am not saying that one is better than the other, or that we should only use music that the children and young people are familiar with, or vice versa. No, the point of lists A and B is to show that the same musical concept can be taught using different resources. These resources can be thought of as the repertoire of classroom teaching materials, and, I will admit, I have been deliberately provocative in choosing the musical items in the two lists. But the point remains, the repertoire of musical examples chosen can become, for those outside of music education, a proxy measure for what is valued. So when you hear a headteacher say “We teach proper music here, Mozart and Beethoven, none of that ‘make up a soundscape about the sea nonsense’”, they are signalling their values, not the quality of the musical teaching and learning. This is because I venture to suggest that it is probably not possible to teach music in a genre-free fashion. Yes, I suppose you could teach pitch using computer generated tones, and rhythm using only clapping, but once ‘real’ music becomes utilised, as surely it must and should, then the thorny problem of genre raises its head.

For music educators, I suspect that the examples of music that they will choose to listen to with their classes will cross a wide gamut of styles, types, eras, and genres. If “Roll out the Barrel” will exemplify the point in question, fine, this does not mean the teacher is promoting drinking songs and alcoholic excess, any more than the Brindisi from Verdi’s la Traviata does! Where this becomes an issue is when external values are bolted on, where the musical choices used are about promoting some form of worthiness. And it is here that as music educators we do have an issue not of our own making but created for us. These are the genre wars which break out in music education fairly frequently, Stormzy vs Mozart being but one recent example.

Where such genre wars are leading is to do with what commentators –often outside music education – believe that one of the purposes of music education should be, namely to make children like classical music. I worry that it is quite hard to make children like anything, and compulsory enjoyment has never been my thing. But I do think we as music educators should be introducing children to music that they may not have heard hitherto. I do think that this is legitimate, I would go so far as to say that we should be doing it, after all English lessons are not often populated with comics as the sole literary form.

Where this all becomes problematic is when we have the intrusion of one of the current contentious terms in education, that being “cultural capital” (written about by Liz Stafford in issue 4.1 of this magazine). Which of lists A and B above contains the most cultural capital? Is that even a thing? Can you measure cultural capital? How? What rating scale should be used? Cultural capital is itself a difficult concept, and often carries within it connotations of Arnold’s phrase “the best that has been thought and said”, which as Phil Beadle observes, can in and of itself be problematic:

(Beadle, 2020 p.42)

And it is this that proponents of high culture (who, to be fair, don’t usually have to try and teach it to children!) find lamentable. What is important to note from a music educator’s perspective is that the genre – the repertoire –is serving a different end. Yes, we will want to introduce pieces of music that the children may not have heard, but we need to do this in a careful and sensitive way so that we do not breed resentment. Saying “OK, oiks, I heard some of you listening to the radio in your cars as your mums drove you to school, and I must say that music was twaddle, your mums clearly have no taste, unlike me” is not going to go down well at the school gates! Now, clearly no teacher would be this insensitive, but we need to watch how we introduce music, and this is because unlike many other school subjects, music is very closely bound up with identity. As Nicholas Cook put it, “In today’s world, deciding what music to listen to is a significant part of deciding and announcing to people not just who you ‘want to be’ . . . but who you are” (Cook, 2000 p.5).

But here’s a thing. Spend long enough following these angry computer keyboard cultural warriors on social media, and you’ll find them saying things like “spent the evening listening to Ed Sheeran…”, or Eurythmics, or E17, or whatever (And why not? no problem!) Seldom, if ever, do they report listening to Franck, Faure, or Frescobaldi.

Yet pity the poor music teacher who says they taught something in a music class using an Ed Sheeran song, never mind that the previous pieces of music they played were by Grieg, Handel, and Ireland (just working my way through the musical alphabet!); no, the fact they played some Ed Sheeran heralds the end of civilisation as we know it! Personally, I think this may be because these keyboard cultural warriors are desperately trying to virtue signal their curricula as making up for something personally that they lack, an interesting variation on “do as I say, not as I do”! Music lessons, as currently configured in the UK, are not musical appreciation lessons. The purpose of employing repertoire is to make musical points, and to ‘teach music musically’, as Swanwick (1999) put it. Music teachers are not the stormtroopers of cultural education enactment; if society wants us to do this, then we need to think about what the purposes of music education are. After all, as Simon Toyne observes:

(Toyne, 2021 p.115)

So what should beleaguered music teachers do? Well, the National Curriculum is actually quite vague on this matter, which might be a good thing! As you know, it says this: The national curriculum for music aims to ensure that all pupils: perform, listen to, review and evaluate music across a range of historical periods, genres, styles and traditions, including the works of the great composers and musicians.

What it does not say is who the great composers or great musicians are. Kanye West currently tops the list of highest-earning musicians; is he a great musician? (I don’t know!) According to the Classic FM website “The best-selling living composer is Howard Shore, followed by Ludovico Einaudi in second place, John Williams in third, and Sir Karl Jenkins in fourth”. Has their music featured recently on your listening list with kids? It is here that the cultural capital-o-meter keyboard warriors might wince. Does Einaudi (to pick but one) have more or less cultural capital than, say, Thomas Adès? How do we decide? Or, more importantly, who gets to decide? The self-appointed keyboard warriors? Hmm! As music teachers we are the architects of our own curriculum, we get to decide what the building blocks of musical learning are, in terms of what works best for us, our kids, in our school. Imagine being told that you had to teach - pick composer or musician you are not too keen on - (for me, Wagner, sorry Wagnerians!), and that the music of said composer had to form the basis of your entire curriculum? Well, if that were me I’d be angry, and then be subverting it like mad! Ok, Wagner (yuk) well here’s some Richard Strauss (better) and here’s some Bruckner (now we’re cooking!). And this could be done with any composer/genre/musical style you name. And we haven’t even started on non-western music yet! After all, as Bernard Trafford wrote:

(Trafford, 2017).

What lies at the heart of this matter is what is and what should be part of the job of the music teacher. Yes, we can and should be introducing our pupils to music they don’t know, and might not come across elsewhere, sure; but our job is to teach music musically, and the musical repertoire we choose for this should be based on our knowledge of our contexts. Look for musical examples and broaden our own horizons, certainly, and introduce these new discoveries while we are enthusiastic about them as and when appropriate, but let’s try and not let ourselves become the cultural warriors in a battle we didn’t pick!

Me? I spent the evening listening to Poulenc choral music, how much cultural capital is there in that? Hmm! However you spent your listening evening, hopefully you did it because you wanted to, not because some trumped-up cultural keyboard warrior shamed you into it!

Professor Martin Fautley is director of research in the School of Education and Social Work at Birmingham City University. He is the author of ten books and over 60 journal articles, book chapters, and academic research papers. He is joint editor of the British Journal of Music Education. @DrFautley