9 minute read

Helping students overcome change and uncertainty

THE CUMULATIVE IMPACTS OF DROUGHT, FLOODS AND BUSHFIRES, COMPOUNDED BY RECURRENT COVID-19 LOCKDOWNS HAVE SIGNIFICANTLY IMPACTED MANY COMMUNITIES. THESE SUCCESSIVE DISASTERS HAVE TAKEN A TOLL ON THE WHOLE SCHOOL COMMUNITY, INCLUDING SCHOOL TEACHERS AND LEADERS WHO ARE THE BACKBONE OF THE SCHOOL AND PROVIDING THE SAFE COMMUNITY HUB.

EThe MacKillop Institute is committed to supporting school professionals to support children and young people impacted by uncertainty and significant change and loss experiences with its Seasons for Growth evidence-based programs to help them understand and respond to adverse life experiences.

The Seasons for Growth (SfG) children and young people’s program was developed in mid1990s in collaboration with Professor Anne Graham AO, Director of the Centre for Children and Young People, Southern Cross University. SfG General Manager, Fiona McCallum tells Education Matters that SfG is an Australian evidence-based, early intervention program that is trauma informed, and delivered to small groups of children and young people over eight weeks. “SfG is based on the belief that change and loss are a part of life, and grief is the normal response to these losses. Often people think about grief as a response to the death of someone we care about – in our work, we describe grief as a response to the major life change and loss,” McCallum says.

“The last 18 months has been challenging for many school communities with the devastating impacts of bushfires and floods and the additional uncertainty and complexity with the COVID-19 pandemic. Recent research suggests that 85 per cent of parents have reported changes in their children during the COVID-19 lockdown.

“Victoria’s Commission for Children and Young People recently cited one third of young people surveyed reported psychological distress as a result of the e pandemic. The experiences can negatively impact children and young people as it affects their development and overall social and emotional wellbeing. We also know that children and young people are more likely to adapt well given the timely and appropriate information and support.”

Other experiences that trigger feelings of loss can include family separation, death, parental unemployment or imprisonment, loss of a pet, illness, change of house or school. These losses can trigger additional impacts including losses of routines, safety, dreams and traditions.

The SfG program aims to provide children with a safe space to come together to reflect on their experiences and to learn knowledge and identify support networks to help them now and in the future.

Over the past 25 years, McCallum says the SfG programs have expanded to meet the increasing needs of communities in Australia and internationally, having supported more than 350,000 children, young people and adults in Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, Scotland, Ireland, England and Wales.

With a commitment to supporting children and young people following experiences of disaster, suicide, forced migration, home-based care, Good Grief can also adapt to support adults, parents/carers, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

“The core intentions of SfG are the development of resilience and emotional literacy in order to promote social and emotional wellbeing, with the overarching aim to improve the quality of life of children and young people,” McCallum says.

“The program activities align the metaphor of the seasons with change loss experiences. We reflect on the changes that we see and feel with the seasons, like the changes in the leaves in Autumn and how we can feel we want to hibernate

The program is based on the belief that change and loss are a part of life, and grief is the normal response to these losses.

in the cold of Winter when times may be difficult. The “seasons” also help us to understand that difficult times will come and go.”

The eight-week small group program, led by a trained facilitator from the school, invites young people to practice new ways of responding to change, and to understand the effects of change, loss and grief while developing skills in communication, decisionmaking, and problem-solving.

“The program incorporates a wide range of ageappropriate creative learning activities with content that is highly visual and makes extensive use of illustrations that have been adapted to be age appropriate across the four different program levels for primary and secondary school-aged children. We support the trained school facilitators with a comprehensive set of materials including manuals and participant journals, access to an online portal with additional resources and ongoing support and learning options,” McCallum says

During a time where students have faced disruptions in the classroom because of COVID-19, McCallum says it is not unusual for children and young people to experience difficulties with understanding and regulating their emotional responses and to engage in learning.

“Students and educators are citing the uncertainty and disruptions as particularly challenging from COVID-19, with students reportedly feeling isolated,” McCallum highlights.

“In the past 12 months we have trained over 1,400 teachers and professionals across Australian schools. The teaching professionals trained in the program frequently report the value of the training and understanding the experience of significant change and loss for children and young people.

“One trained facilitator recently descried SfG as so essential in being a preventative measure for kids.”

McCallum describes the importance of working with the school systems and the Beyou wellbeing teams to support the integration of SfG with other school wellbeing initiatives.

“A great example of this collaboration is the support provided in NSW through partnering with the Department of NSW Education to support schools in bushfire impacted areas,” she says.

The SfG program not only provides support for children. Resources are developed for parents and carers to support the wellbeing of their children.

McCallum says research has indicated that the capacity of parents and carers is often impaired following major change and loss in families.

“Our resources are available on the website and we invite schools to share these in their communities. We also provide online sessions for professionals, parents and carers.”

Part of The MacKillop Institute, the SfG program also meets the Australian Professional Teaching Standards, with the third edition of the program released in 2015 to reflect developments in research evidence and practice wisdom, strengthening the program links with theoretical frameworks.

McCallum says after speaking with school leaders, mental health and wellbeing teams, and community members about the impacts of the 2020 bushfires and concerns for mental health of children following COVID-19, it has partnered with Professor Graham to review the evidence and the views of children and their families to understand their experiences of natural disasters and the pandemic.

“This research evidence is foundational to the SfG programs, and new evidence will continue to inform updates to the programs,” she says.

“A trained facilitator from the NSW south coast captured the value of the program recently, stating that Seasons for Growth is really a program for the times we are living in.’’ EM

The Seasons for Growth program is part of the MacKillop Institute and was developed in the mid-1990s. The Seasons for Growth programs have expanded to meet the increasing needs of communities in Australia.

www.goodgrief.org.au Good Grief is on Facebook and LinkedIn www.mackillopinstitute.org.au

Insights on the wellbeing of school leaders throughout COVID-19

RESEARCH FROM DEAKIN’S EDUCATOR HEALTH AND WELLBEING TEAM HAS UNCOVERED THAT WHILE THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC HAS BEEN A MIXED BAG FOR EDUCATORS, SCHOOL LEADERS’ FAITH IN THEIR ROLES REMAINS LARGELY POSITIVE. DEAKIN UNIVERSITY POST-DOCTORAL RESEARCH FELLOWS BEN ARNOLD, MARK RAHIMI AND MARCUS HORWOOD (OF THE HEALTH AND WELLBEING TEAM) RECOUNT.

EOver the last year, concern has grown about the health and wellbeing of education professionals. Preventative measures aimed at addressing the coronavirus pandemic, such as the partial or complete closure of schools, colleges and universities, have had a significant impact on those working in the education sector. In many contexts, educators have been required to adapt to a ‘new normal’ where they work on the frontline of the pandemic alternating between face-to-face and online teaching and caring for the health and wellbeing of their school community.

The question of how to promote the development of safe, healthy work environments for educators their communities is of particular interest for us in Deakin’s Educator Health and Wellbeing Team.

Formed by Professor Phil Riley in 2018, we track education professionals working environments and health and wellbeing over time.

We currently undertake research with educators at all levels of the education system, from early childhood through to tertiary education,

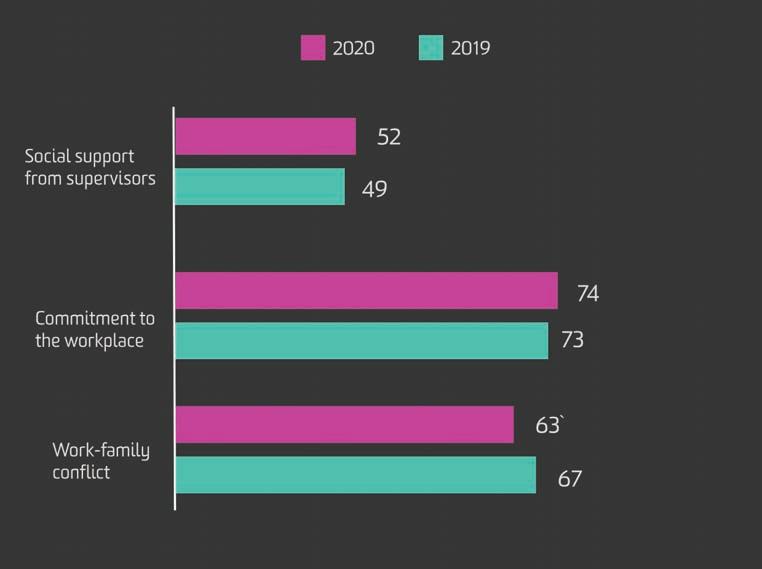

Figure 1: Australian School Leaders’ interpersonal relations at workplace in 2019 and 2020 (%) to investigate how their workplace and work tasks impact on their mental and physical health. Our aim is to provide researchers, policymakers and educational leaders with evidence that can be used to establish healthy, safe working environments.

We also embed our discoveries and knowledge into Deakin’s postgraduate education courses, to better prepare the leaders of the future, and into educational policy and practice.

This year, we drew on Professor Phil Riley’s research into school leaders to map school leaders’ experiences of work during 2020 – the first year of the pandemic – and identify the issues and opportunities facing this group of educators in this current context.

While working conditions have been unfavourable, we were pleased to discover that school leaders reported some positive changes to their work environment.

SEVERAL DISRUPTIONS AND DECLINING FAIRNESS AT WORK

School leaders reported that while their workloads declined slightly, they continued to be a major burden and source of stress.

Our analysis also found that school leaders’ work environments changed during the 2020 and became more fluid and unstable.

School leaders reported that their work was less predictable in 2020 and they were less clear about the exact nature of their job role, expressing more doubt about their workplace tasks, duties and responsibilities.

School leaders also reported considerably lower levels of justice at their place of work in 2020, meaning that workplace procedures, interactions and the distribution of work were perceived to be less fair than in previous years.

STRONGER RELATIONSHIPS AND BETTER WORK-LIFE BALANCE

But despite these challenges, school leaders also appeared to experience a number of positive changes at work during 2020.

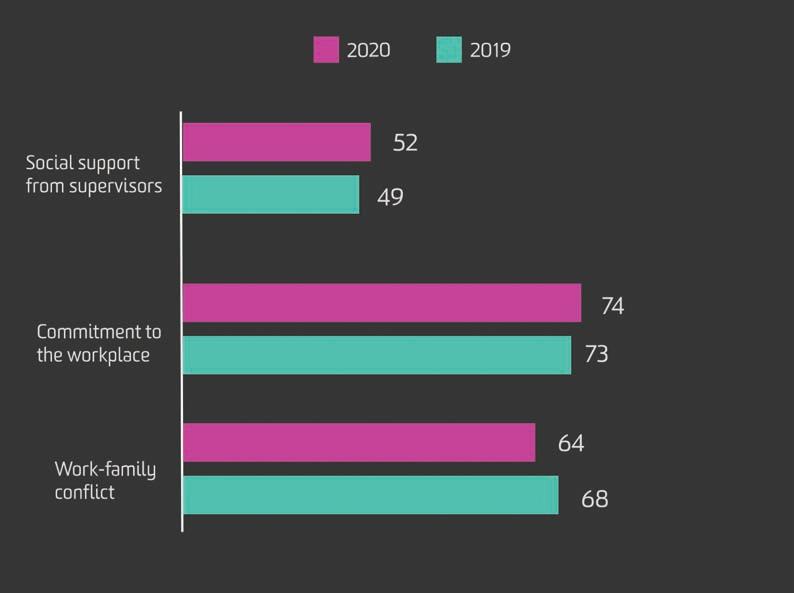

School leaders reported receiving greater levels of support from their supervisors and colleagues, and reported a stronger sense of commitment to work during the first year of the pandemic.

Contradictory to some reports, school leaders also reported having a significantly better balance between

Figure 2: Australian School Leaders Social Support and Work Life Balance in 2019 and 2020 (%).

Deakin’s Educator Health and Wellbeing Team are investigating how educators’ workplace and work tasks impact on their mental and physical health. work and their home lives, with work less frequently affecting the time they spent with family members and the energy they had available at home in 2020.

AUSTRALIAN SCHOOL LEADERS SOCIAL SUPPORT AND WORK LIFE BALANCE IN 2019 AND 2020 (%)

Overall, the changes forced by the pandemic to the work environment appear to have affected school leaders’ mental health and wellbeing. Compared to 2019, school leaders reported an increase in levels of stress and burnout in 2020.

Although less is known about the impact of the pandemic on the work and wellbeing of school teachers and early childhood educators, anecdotal evidence suggests that these education professionals have been significantly impacted.

At Deakin, we’re committed to undertaking robust research involving these groups of educators to better investigate their current working conditions and the status of their mental and physical health and wellbeing.

To learn more about Deakin’s School of Education and research priorities in education and teaching, visit deakin.edu.au/education EM

Buyer’s Guide

Deakin University Ph: 1800 963 888 Email: myfuture@deakin.edu.au Web: www.deakin.edu.au/education